Abstract

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is highly prevalent with an estimated occurrence in the US of over 1.3 million per year. While one consequence of mTBI is impulsive aggressive behavior, very few studies have examined the relationship between history of mTBI in impulsively aggressive individuals. In this project, we examined the relationship between history of mTBI in healthy control (HC; n = 453), psychiatric control (PC; n = 486), and in study participants with Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED; n = 695), a disorder of primary impulsive aggression. We found that IED study participants were significantly more likely to have a history of mTBI (with or without history of a brief loss of consciousness) compared to both HC and PC study participants. A similar observation was made for self-directed aggression (i.e., suicidal or self-injurious behavior) although group differences in this case was only among those with mTBI with loss of consciousness. For both other- and self- directed of aggression variables, we observed a stepwise increase in dimensional aggression and impulsivity scores across participants as a function of mTBI history. Given that impulsive aggressive behavior begins very early in life, these data are consistent with the hypothesis the lifelong presence of an impulsive aggressive temperament places impulsive aggressive individuals (IED) in circumstances that put them at greater risk for mTBI compared with other individuals with and without non-impulsive aggressive psychopathology.

Keywords: IED, Psychosocial Function, Life Satisfaction

INTRODUCTION

According to the VA/DoD, mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is defined as head injury that may result in alteration of consciousness, post-traumatic amnesia (up to 24 hours post injury), and/or possible loss of consciousness (less than 30 minutes) that may or may not be visible on structural imaging (e.g. CT scan [1]). MTBI is highly prevalent, with an estimated occurrence of over 1.3 million injuries annually in the United States [2]. However, this is likely a significant underestimate of true mTBI injuries, as many people who suffer from mild head injury do not seek medical treatment [3]. Rates among military servicemen have been estimated to be even higher, with an estimated rate of 15% of returning OEF/OIF soldiers suffering from mTBI [4]. mTBI is associated with a number of cognitive, physical and emotional sequelae that typically resolve within three months of injury [1]. However, a growing body of research indicates that anywhere from 10–31% of post-mTBI patients experience symptoms, including lingering physical symptoms and mood disturbances, beyond the three-month period [5, 6]. Factors associated with more persistent post-mTBI symptoms include female gender, older age, pre-existing psychiatric issues, and medical complications [7, 8]. However, it should be noted that mTBI is a diagnostically heterogeneous group, due to both the variability in symptom presentation and severity (whether there is LOC, PTA uncomplicated vs. complicated injury), as well as variability in understanding and application of mTBI terminology and classification among healthcare providers [9,10].

A growing of area of interest related to post-concussive/mTBI symptoms includes changes in aggressive behavior, both in verbal and physical forms, after head injury [11]. Among those with history of TBI, aggression may be due to a combination of both neuropsychological and emotional deficits, including decreased inhibition and increased frustration [12], a relationship well established in criminal populations. For example, Slaughter et al., [13] reported that 58% of incarcerated subjects reported having ever suffered from an mTBI, while 29% reported suffering from an mTBI within the previous year. Compared to those with remote or no history of TBI, those who reported a TBI within the past year exhibited greater neuropsychological deficits related to phonemic verbal fluency and mental flexibility, both of which are associated with frontal networks dysfunction. Moreover, those who endorsed recent history of TBI reported significantly higher levels of anger and aggression on the BAAQ compared to controls. Importantly, the two groups did not differ in psychiatric disorder prevalence. Similarly, increased TBI is also found in domestic violence perpetrators [14, 15]. The relationship between aggression post-TBI has also been noted in non-incarcerated populations [16]. Further, those who exhibit aggressive behavior after head injury tend to also have greater difficulty with activities of daily living and social functioning [17].

The directional causality between TBI and aggression remains in question, however. Several studies suggest that pre-existing disturbances of mood, or aggressive behavior, are predictive of future post-TBI aggressive behavior. For example, Tateno et al. [18] reported predictive factors of post-TBI aggression to be pre-injury substance abuse, mood, or aggressive disorders. Studies of veterans and returning military personnel further report that PTSD symptoms, mood disturbance, suicidality, substance abuse or misuse, lower education, and previous history of arrest or domestic violence more predictive of aggression than presence of TBI itself.[19–22] In contrast, Ramesh et al., [23] reported that previous history of TBI preceding initiation of cocaine use may increase risk of substance abuse.

Advancements in neuroimaging and biomarkers speak to structural differences among the brains of those with history of TBI and aggression. Epstein et al. [24] found evidence of increased aggression, anxiety, and depression as well as cortical thinning of the right orbito-frontal cortex among those with history of mTBI [24], although similar abnormalities are observed as a function of aggression regardless of history of mTBI [25]. In addition, research indicates reduction of fractional anisotropy, associated with reduced white matter functioning in fronto-temporo-occipital regions, in those with history of mTBI [26]. Lastly, a systematic review of the concussion/mTBI biomarker literature indicated a number of biomarkers associated with irritability and aggression in mTBI, including COMT, SLC6A4 (SERT) and MMP-9 proteins [27].. A number of studies have also demonstrated correlations between the number of head injuries and aggression, with higher number of concussions/mTBI resulting in higher levels of aggression and irritability [28]. Thus, while a relationship between head injury and aggression exists, additional research is needed to more fully characterize the nature of this relationship especially in individuals with mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI).

The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between history of mTBI and aggression in a large clinical research sample of physically healthy individuals with and without psychiatric disorder, including Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED), a disorder of outwardly directed impulsive aggression [29]. We hypothesized that: a) study participants with IED would be more likely to have a history of mTBI compared with both healthy and psychiatric controls, b) study participants with history of self-directed aggression (suicidal and/or self-injurious behavior) would be more likely to have a history of mTBI compared with those without this history and, c) study participants with a history of mTBI would have higher trait aggression and trait impulsivity scores compared with those without this history. Finally, we hypothesized that measures of aggression and impulsivity would follow a step-wise increase in magnitude as a function of severity of mTBI history (e.g., no mTBI vs. mTBI without loss of consciousness vs. mTBI with loss of consciousness).

METHODS

Participants

1,634 adult individuals participated in this study. All participants were physically healthy and were systematically evaluated in regard to aggressive and other behaviors as part of a larger program designed to study correlates of impulsive aggressive, and other personality-related, behaviors in human subjects. Subjects were recruited through public service announcements, newspaper, and other media, advertisements seeking out individuals who: a) reported psychosocial difficulty related to one or more psychiatric conditions or, b) had little evidence of psychopathology. All subjects gave informed consent and signed the informed consent document approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Diagnostic Assessment

Syndromal and personality disorder diagnoses were made according to DSM-5 criteria. Diagnoses were made using information from: (a) the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Diagnoses (SCID-I; [30]) for syndromal (formerly Axis I) disorders and the Structured Interview for the Diagnosis of DSM Personality Disorder for Personality (formerly Axis II) Disorder [31]; (b) clinical interview by a research psychiatrist; and, (c) review of all other available clinical data. This process resulted in good to excellent inter-rater reliabilities (mean kappa of .84 ± .05; range: .79 to .93) across anxiety, mood, substance use, impulse control, and personality disorders. Final diagnoses were assigned by team best-estimate consensus procedures involving research psychiatrists and clinical psychologists as previously described [32]. Subjects with a current history of a substance use disorder or of a life history of any bipolar disorder, schizophrenia (or other psychotic disorder), or mental retardation/intellectual disability, were excluded from the study. In addition, participants with history of traumatic brain injury (mTBI) with loss of consciousness of greater than 30 minutes were excluded from study (see below).

After diagnostic assignment, 453 participants had no evidence of any psychiatric diagnosis and as such were designated “Healthy Controls” (HC); 486 participants met criteria for a current/lifetime diagnosis of a syndromal psychiatric disorder and/or a personality disorder but not for Intermittent Explosive Disorder (“Psychiatric Controls”: PC), and 695 participants met criteria for Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED). Of the 1,181 participants with history of a psychiatric disorder, a majority (67.6%) reported: a) history of formal psychiatric evaluation and/or treatment (52.8%) or, b) history of behavioral disturbance during which the subject, or others, thought they should have sought mental health services but did not (14.7%). Table I listed the means (±SD) for demographic, psychosocial functional/life satisfaction, and psychometric behavioral variables for the three groups; Table II lists the syndromal and personality disorder diagnoses for the two psychiatric (PC and IED) groups.

TABLE I.

Demographic, Functional, and Psychometric Characteristics of Study Participants

| HC (N = 453) |

PDC (N = 486) |

IED (N = 695) |

P* | Group Differences |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Variables | |||||

| Age | 30.4 ± 9.0 | 32.3 ± 9.6 | 35.8 ± 10.0 | < 0.001a | HC < PC < IED |

| Gender (% Male) | 56.5% | 58.6% | 54.5% | = 0.373b | HC = PC = IED |

| Race (% White) | 55.8% | 56.8% | 51.7% | = 0.009b | HC = PC > IED |

| SES Score | 40.4 ± 13.6 | 33.2 ± 13.9 | 36.0 ± 13.0 | < 0.001a | HC > IED > PC |

| Psychosocial Function | |||||

| GAF Score | 83.3 ± 5.4 | 64.3 ± 11.6 | 55.8 ± 8.0 | < 0.001a | HC > PC > IED |

| Q-LES-Q Score | 52.2 ± 7.9 | 45.2 ± 10.2 | 39.0 ± 10.4 | < 0.001a | HC > PC > IED |

| Psychometric Variables | |||||

| Aggression: LHA | 4.7 ± 3.6 | 8.2 ± 5.6 | 18.0 ± 4.5 | < .001 | HC < PC < IED |

| Aggression: BPA | 27.9 ± 10.1 | 33.7 ± 11.7 | 46.6 ± 11.9 | < .001 | HC < PC < IED |

| Impulsivity: LHIB | 22.6 ± 15.6 | 35.8 ± 20.2 | 52.8 ± 20.0 | < .001 | HC < PC < IED |

| Impulsivity: BIS-11 | 55.4 ± 9.2 | 63.5 ± 10.7 | 68.6 ± 11.5 | < .001 | HC < PC < IED |

Means ± SD based on raw data; statistics based on one-way ANCOVA (age, sex, ethnicity, and SES score as covariates).

TABLE II.

Syndromal and Personality Disorder Diagnoses Among Study Participants

| PC (N = 486) |

IED (N = 695) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Syndromal Disorders: | |||

| Any Depressive Disorder | 80 (16.5%) | 152 (21.9%) | = 0.021 |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 87 (17.9%) | 161 (23.2%) | = 0.030 |

| Stress and Trauma Disorders | 23 (4.7%) | 87 (12.5%) | < 0.001* |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders | 5 (1.0%) | 27 (3.9%) | = 0.003 |

| Eating Disorders | 13 (2.7%) | 37 (5.3%) | = 0.028 |

| Somatoform Disorders | 7 (1.4%) | 12 (1.7%) | = 0.816 |

| Non-IED Impulse Control Disorders | 2 (0.4%) | 10 (1.4%) | = 0.137 |

| Lifetime Syndromal Disorders: | |||

| Any Depressive Disorder | 218 (44.9%) | 417 (60.0%) | < 0.001* |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 116 (23.9%) | 206 (29.6%) | = 0.029 |

| Any Substance Use Disorder | 170 (35.0%) | 353 (50.8%) | < 0.001* |

| Stress and Trauma Disorders | 60 (12.8%) | 145 (20.9%) | = 0.001* |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders | 9 (1.9%) | 36 (5.2%) | = 0.003 |

| Eating Disorders | 37 (7.6%) | 74 (10.6%) | = 0.085 |

| Somatoform Disorders | 7 (1.4%) | 13 (1.9%) | = 0.652 |

| Non-IED Impulse Control Disorders | 5 (1.0%) | 24 (3.5%) | = 0.007 |

| Personality Disorders: | |||

| Cluster A (Odd) | 42 (8.6%) | 121 (17.4%) | < 0.001* |

| Cluster B (Dramatic) | 99 (20.4%) | 319 (45.9%) | < 0.001* |

| Cluster C (Anxious) | 109 (22.4%) | 180 (25.9%) | = 0.191 |

| PD-NOS | 149 (30.7%) | 231 (33.2%) | = 0.376 |

p < 0.05 after correction for multiple comparisons (uncorrected p < 0.003).

Assessment for History of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI)

History of mTBI was recorded directly from the study participant during the diagnostic assessment interview using a structured interview of our own design that contained most, but not all, of the items in the Ohio State University TBI-ID (OSU-TBI-ID; [33]); the TBI-IQ was developed during the later stages of our data collection and was, thus, not available for this study. mTBI was defined as self-reported history of a blow to the head associated with mild, and brief, neurological symptoms typically associated with mTBI including any of the following: feeling dazed or dizzy, disorientation, memory difficulties lasting less than 24 hours, and loss of consciousness of less than 30 minutes). Potential participants with history of a blow to the head and a period of loss of consciousness (LOC) for more than 30 minutes were not included in this study.

Assessment of Aggression, Impulsivity, and Related Behaviors

In this study, aggression was conceptualized as behavior by one individual directed at another person or object in which either verbal force or physical force is used to injure, coerce, or to express anger. As such, aggression was assessed with the aggression scales of the Life History of Aggression (LHA [34]) assessment and of the Buss-Perry Aggression (BPA [35]) questionnaire. LHA Aggression assesses history of actual aggressive behavior while the BPA assesses aggressive tendencies as a personality trait. LHA Aggression is a widely used five-item measure that quantitatively assesses one’s life history of overt aggressive behavior (i.e., aggressive thoughts/urges are not counted). It is conducted as a semi-structured interview. Internal consistency (α = 0.87), inter-rater reliability (r = 0.94), and test-retest reliability (r = 0.80) is good-to-excellent. BPA Aggression, also a widely used assessment of trait aggression, is composed of the BPA’s Verbal Aggression and Physical Aggression subscales and has good psychometric properties. Impulsivity was assessed with the Life History of Impulsive Behavior (LHIB [36]) and with the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11 [37]). The LHIB assesses history of actual impulsive behavior and is conceptually similar to the LHA. It includes 20 items regarding impulsive behavior and is scored on a five point ordinal scale (as is the LHA). The LHIB demonstrates good internal consistency (α = .96) and test-retest reliability (r = .88). Psychosocial function was assessed with the Global Assessment of Function (GAF [38]) scale and satisfaction of life experience was assessed by the Quality of Life Experience and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q [39]).

Statistical Analysis and Data Reduction

For analytic purposes, mTBI was divided into those without history of mTBI (n = 1356; 83.0%), those with a history of mTBI but without loss of consciousness (LOC; n = 168; 10.3%), and those with history of mTBI and a brief period of LOC lasting less than 30 minutes (n = 110; 6.7%). Statistical procedures included Chi-square, t-test, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) as appropriate. All reported analyses were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, and socio-economic status. A two-tailed alpha value of 0.05 was used to denote statistical significance for all analyses except in cases where a correction for multiple comparisons was more appropriate. Data reduction involved the creation of composite variables for trait aggression and trait impulsivity. As each of the individual variables related to these dimensions were highly correlated with each other, composite variables were created by z-transforming each individual variable and taking the mean z-score of each of the related variables. Post-hoc analyses involved adjustment for comorbid syndromal disorders (lifetime, depressive, substance use, and stress/trauma disorders).

RESULTS

Demographic and Psychometric Characteristics of the Sample (Table I)

The three diagnostic groups differed modestly, but significantly, in age, socioeconomic score, ethnicity distribution but not in distribution of sex. Accordingly, all relevant analyses factored in these demographic differences. The groups significantly differed in all psychosocial function/satisfaction and in all psychometric behavioral variables, as expected. Finally, PC and IED groups did not significantly differ in rates of syndromal comorbidity with the exception of lifetime depressive, lifetime substance use, and current and lifetime stress/trauma disorders (Table II).

History of mTBI Among Study Participants (n = 268)

Among the mTBI without reported history of LOC (n = 168), 78.1% reported only one mTBI, 13.7% reported only two, and 8.3% reported three or more mTBIs. Of the total mTBI group reporting mTBI with LOC (n = 110), 84.5% reported one mTBI with LOC, 10.9% two mTBIs with LOC, and 4.5% three or more mTBIs LOC.

History of mTBI Without LOC (mTBI) and mTBI With LOC (mTBI/LOC) as a Function of Diagnostic Group

IED participants had a significantly greater history of mTBI and mTBI/LOC compared with both HC and PC participants (Table III). The two control groups did not differ in this regard and, thus, these groups were combined for subsequent analysis. These results were not changed when adding disorders with a higher rate of comorbid IED (see above), added as a separate layered factor to the Chi-square analysis.

TABLE III.

Relationship between Diagnostic Groups and History of mTBI With and Without History of Brief Loss of Consciousness (LOC)

| Group | No mTBI | mTBI / LOC− | mTBI / LOC+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| HC | 403 (89.0%) | 32 (7.1%) | 18 (4.0%) |

| PC | 428 (88.1%) | 40 (8.2%) | 18 (3.7%) |

| IED | 525 (75.5%) | 94 (13.5%) | 76 (10.9%) |

Overall X2 = 51.32, df = 4, p < 0.001.

Relationship Between Number of Reported Head Injuries and Number of Reported LOC Episodes with Measures of Aggression and Impulsivity

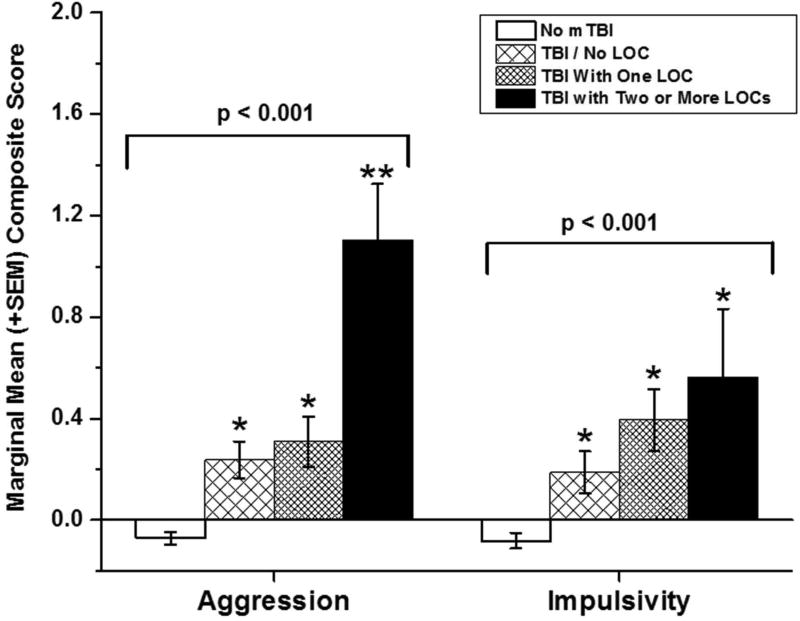

Next, we examined the relationship between composite aggression and impulsivity scores with the number of mTBI/LOC episodes. We used four categories for this analysis: No history of mTBI, mTBI without LOC, mTBI with one LOC episode, and mTBI with two or more LOC episodes. ANCOVA revealed a significant effect for aggression scores as a function of reported mTBI/LOC (F[3,1515] = 17.73, p < 0.001); fig 1, left. Aggression scores of those reporting history of mTBI without LOC were higher than those without history of mTBI, but similar to those of participants reporting history of one LOC episode. Participants reporting two more LOC episodes, however, had the highest aggression scores of all groups. Adding IED status to the model did not change these results (F[3,1514] = 6.11, p < 0.001). ANCOVA with impulsivity scores revealed a similar result (F[3,1058] = 8.80, p < 0.001) but with a stepwise fashion increase in impulsivity scores from the “no mTBI” group to the “two or more mTBI/LOC episode” group; fig 1, right. Adding IED status to the model reduced this result to a trend for statistical significance (F[3,1057] = 2.26, p = 0.08).

Figure 1.

Marginal means (± SEM) composite aggression (left) and impulsivity (right) scores for reported history of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) with and without history of one or more brief episodes of loss of consciousness (LOC). Single asterisk signifies a significant difference compared with the “No mTBI” group; double asterisk for aggression scores (left) signifies a significant difference for two or more LOC episodes compared with the mTBI Only and the One LOC group which did not differ from each other.

Association of mTBI/LOC and History of Self-Aggressive (S-AGG) Behavior

Study participants with a history of suicide attempt (SA), history of self-injurious behavior (SIB), and history of either (SA and/or SIB), had a significantly increased rate for history of mTBI with LOC, but not for mTBI without LOC, compared with control participants (Tables IVa–c).

TABLE IV.

Relationship between History of Suicidal (SA) and/or Self-Injurious Behavior (SIB) and History of mTBI With/Without History of Brief Loss of Consciousness (LOC)

| Group | No mTBI | mTBI / LOC− | mTBI / LOC+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| No SA | 1205 (84.1%) | 138 (9.6%) | 90 (6.3%) |

| SA | 151 (75.1%) | 22 (10.9%) | 28 (13.9%)a |

| Group | No mTBI | mTBI / LOC− | mTBI / LOC+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| No SIB | 1227 (83.7%) | 147 (10.0%) | 92 (6.3%) |

| SIB | 129 (76.8%) | 13 (7.7%) | 26 (15.5%)b |

| Group | No mTBI | mTBI / LOC− | mTBI / LOC+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neither SA or SIB | 1144 (84.7%) | 131 (9.7%) | 76 (5.6%) |

| SA and/or SIB | 212 (74.9%) | 29 (10.2%) | 42 (14.8%)c |

Overall X2 = 16.30, df = 2, p < 0.001;

SA+ > SA−

Overall X2 = 19.34, df = 2, p < 0.001;

SIB+ > SIB−

Overall X2 = 30.28, df = 2, p < 0.001;

SA/SIB+ > SA/SIB−

Relationship Between Number of Reported mTBI With and Without Number of Reported LOC Episodes with Measures of Aggression and Impulsivity as a Function of S-AGG

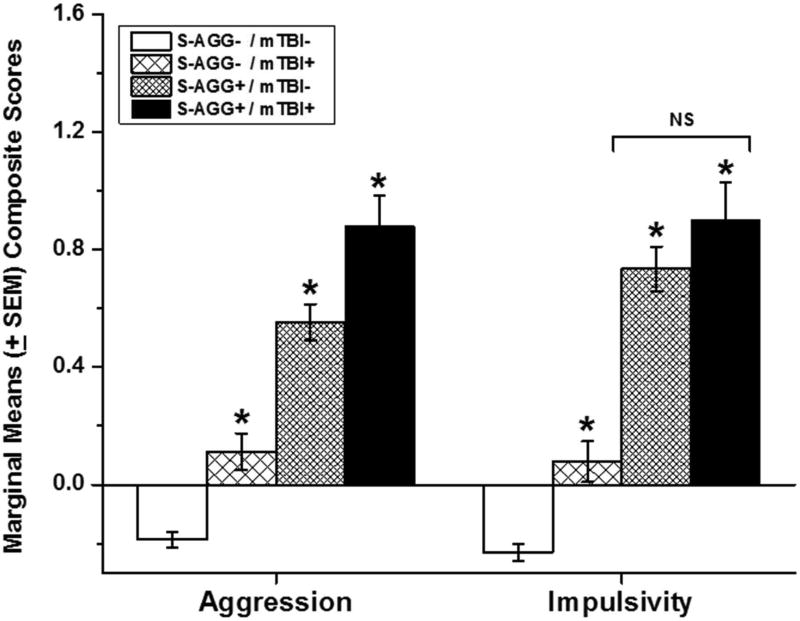

ANCOVA of aggression and impulsivity scores, as a function of S-AGG and mTBI with or without LOC, revealed no differences between number of mTBIs with and without LOC. Thus, these groups were combined for further analysis. Subsequent ANCOVA revealed a significant stepwise increase in aggression scores from S-AGG−/mTBI− to S-AGG+/TBI+ (F[3,1515] = 66.72, p < .0.001); figure 2, left. While a similar ANCOVA analysis, with impulsivity scores, was also statistically significant (F[5,1056] = 38.60, p < 0.001) impulsivity scores displayed a different pattern of results in which S-AGG−/mTBI+ participants had higher impulsivity scores than S-AGG−/mTBI− participants but with S-AGG+/mTBI− and S-AGG+/mTBI+ participants having similar impulsivity scores, each significantly higher than those among both groups of S-AGG− participants; figure 2, right.

Figure 2.

Marginal means (± SEM) composite aggression (left) and impulsivity (right) scores for reported history of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) as a function of self-directed aggressive behavior (S-AGG). Single asterisk signifies a significant difference compared with the “No S-AGG” group and from each other except where specified.

DISCUSSION

The key finding from this study is that individuals with Intermittent Explosive Disorder (i.e., other-directed aggression) are significantly more likely to have a history of mTBI (with or without history of a brief loss of consciousness) compared with both healthy and psychiatric controls. A similar observation was made for self-directed aggression (i.e., suicidal or self-injurious behavior) although the group difference was only among those with mTBI and loss of consciousness. For both variables, we observed a stepwise increase in aggression and in impulsivity scores going from no history of mTBI to mTBI with two or more mTBIs with loss of consciousness. At the very least, these findings support the hypothesis that individuals with IED, as well as those with history of suicidal and/or self-injurious behavior, are at greater risk for mTBI with or without loss of consciousness compared those without IED or these self-aggressive behaviors. However, these findings also highlight the potential role of altered mental state (AMS) or LOC in contributing to additional structural impairment that may be difficult to observe on traditional neuroimaging methodology (e.g. CT) and thus may contribute to a delayed or complicated recovery. Although the role of AMS/LOC in mTBI in complicated recovery remains unclear, there have been several studies that indicate greater neurobehavioral and neuropsychological impairment, as well as structural white matter changes, among those who report mTBI with LOC compared to mTBI with no LOC or healthy controls [40,41].

Differences in rates of mTBI, with or without loss of consciousness, between IED and HC participants was expected given the fact that individuals with substantial psychopathology (i.e., IED) are more likely to differ from healthy controls on most behavior variables. However, the observation that IED participants also differed from PC participants, who also differed from HC participants on many of the variables tested, suggests that the association between IED and history of mTBI was not due simply to general psychopathology. Differences in mTBI rates were accompanied by dimensional increases in aggression (and impulsivity) scores and, thus, differences in mTBI rates may be accounted for by elevations in these specific behavioral traits.

Analysis of composite scores for trait aggression and impulsivity revealed that each behavioral trait was significantly elevated as a function of mTBI (with or without loss of consciousness) compared with study participants without positive mTBI history. Controlling for the presence of IED reduced the magnitude of these relationships but did not eliminate the statistical significance of this result for either composite aggression or impulsivity scores. In actuality, our post-hoc analysis likely underestimates the relationship between aggression/impulsivity scores and mTBI. Since IED participants have high scores on aggression and impulsivity, a high proportion of the variance associated with aggression/impulsivity was removed using IED as a covariate. However, even controlling for the presence of IED indicates greater aggression and impulsivity among those with history of mTBI compared with those without history of mTBI.

Based on this data alone, we cannot say if the presence of high trait impulsivity and aggression, led IED participants to be in circumstances that increase risk for mTBI, or if history of mTBI altered the brains of mTBI participants leading to an increase in aggressive and impulsive behavior post-mTBI. This is because we did not systematically collect data regarding mTBI in relationship to the onset of IED. That said, impulsive aggressive behaviors are present from very early life [42] and individuals with this temperament are likely to place themselves in circumstances associated with bodily injury, including mTBI. Additionally, these findings are in general agreement with the results of studies examining individuals soon after mTBI [18–22] which report that pre-morbid aggression better predicts the occurrence of post-TBI aggression than recent history of mTBI itself. While it is known that TBI, and certainly severe TBI, can be associated with changes in brain structure [24] and with changes in personality features, including aggression [24], we have found that changes in brain structure changes in IED participants were not influenced by history of mTBI [25]. This is not to suggest that changes in brain structure and/or function, and aggressive behavior, associated with mTBI do not occur. We suggest, simply, that presence of mTBI in these study participants was likely due to the dimensional presence of impulsive aggressive behavior, across individuals, rather than to a primary effect of mTBI on measures of aggression and impulsivity.

This study has several strengths and limitations. First, our large participant sample provided extensive diagnostic and phenomenologic information and data from reliable and valid measures of aggression and impulsivity. Its second strength is its inclusion of a non-healthy control group with substantial psychopathy and significantly lower scores on measures of aggression and impulsivity compared to IED study participants. This psychiatric control group is useful, as it helps account for the effect of general, non-aggressive, psychopathology on history of mTBI. Third, while the psychiatric subjects in the study were not primarily recruited from treatment settings, most (67.6%) had history of formal treatment for psychiatric disorder (52.8%) or of behavioral disturbance that should have been assessed by mental health professionals (14.7%). Accordingly, most of the psychiatric subjects in this study are likely to be similar to those drawn from a treatment setting. Limitations include the self-report nature of history of mTBI as well as the non-systematic collection of timing data and the nature of the mTBIs. While most reported that these mTBIs occurred during a sport activity or during a motor-vehicle accident, we did not record the exact context in many cases. However, it was known that none of the participants experienced more than a mild TBI, as our study inclusion criteria required that any history of traumatic brain injury be limited to a head injury associated with less than 30 minutes of a loss of consciousness; on average, current study participants with history of mTBI reported less than 5 minutes.

CONCLUSION

Individuals with Intermittent Explosive Disorder, and individuals with a history of suicidal/self-injurious behavior, are significantly more likely to have a history of mTBI compared with appropriate comparison groups. In both cases of other- and self-directed aggression, a stepwise increase in aggression and in impulsivity scores was observed as a function of type and number of mTBI episodes. These findings support the hypothesis that individuals with IED, as well as those with history of suicidal and/or self-injurious behavior, are at greater risk for mTBI with or without loss of consciousness compared those without IED or these self-aggressive behaviors. While it is likely that impulsive and aggressive traits, which are evident very early in life, place impulsive aggressive individuals in circumstances in which physical, and head, injury will occur, our data do not allow us to reach this firm conclusion. Evaluation of those with IED and/or self-directed aggression should include questions about history of head injury with or without loss of consciousness.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health: RO1 MH60836, RO1 MH66984, RO1 MH104673 (Dr. Coccaro) and the Pritzker-Pucker Family Foundation (Dr. Coccaro).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Coccaro reports being a consultant to and being on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Azevan Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and of Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and being a current recipient of a grant award from the NIMH. Dr. Mosti reports no conflicts of interest regarding this work.

References

- 1.VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Concussion/mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Department of Defense; Office of Verteran Affairs; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC Grand Rounds. Reducing severe traumatic brain injury in the United States. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62(27):549–552. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(27):549–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voss JD, et al. Update on the Epidemiology of Concussion/Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2015;19(7):32. doi: 10.1007/s11916-015-0506-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoge CW, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(5):453–463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean PJ, O’Neill D, Sterr A. Post-concussion syndrome: prevalence after mild traumatic brain injury in comparison with a sample without head injury. Brain Injury. 2012;26(1):14–26. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2011.635354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinos P, et al. Postconcussion syndrome after mild traumatic brain injury in Western Greece. J Trauma Acute Care Surgery. 2010;69(4):789–794. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181edea67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll LJ, et al. Prognosis for mild traumatic brain injury: Results of the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Med (Suppl.) 2004;43:84–105. doi: 10.1080/16501960410023859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landre N, et al. Cognitive functioning and postconcussive symptoms in trauma patients with and without mild TBI. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;21(4):255–273. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristman VL, Borg J, Godbolt AK, Salmi LR, Cancelliere C, Carroll LJ, et al. Methodological issues and research recommendations for prognosis after mild traumatic brain injury: results of the International Collaboration on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prognosis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014;95(3 Suppl):S265–S77. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Easter JS, Haukoos JS, Meehan WP, Novack V, Edlow JA. Will neuroimaging reveal a severe intracranial injury in this adult with minor head trauma? The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314:2672–2681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy D, et al. Correlates and Prevalence of Aggression at Six Months and One Year After First-Time Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017 doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.16050088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alderman N. Contemporary approaches to the management of irritability and aggression following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2003;13(1–2):211–240. doi: 10.1080/09602010244000327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slaughter B, Fann JF, Ehde D. Traumatic brain injury in a county jail population: prevalence, neuropsychological functioning and psychiatric disorders. Brain Injury. 2003;(17):731–741. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000088649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrer TJ, Frost RB, Hedges DW. Prevalence of traumatic brain injury in intimate partner violence offenders compared to the general population: a meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, Abuse. 2012;13:77–82. doi: 10.1177/1524838012440338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrer TJ, Frost RB, Hedges DW. Prevalence of traumatic brain injury in juvenile ofenders: a meta-analysis. 2013;19:225–234. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2011.647901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyer KF, et al. Aggression after traumatic brain injury: analyzing socially desirable responses and the nature of aggressive traits. Brain Injury. 2006;20:1163–1173. doi: 10.1080/02699050601049312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao V, et al. Aggression after traumatic brain injury: prevalence and correlates. J Neuropsych Clinical Neurosci. 2009;21:420–429. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.21.4.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Clinical correlates of aggressive behavior after traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15(2):155–160. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elbogen EB, et al. Protective factors and risk modification of violence in Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(6):e767–773. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallaway MS, et al. Factors associated with physical aggression among US Army soldiers. Aggress Behav. 2012;38(5):357–367. doi: 10.1002/ab.21436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacManus D, et al. Violent behaviour in U.K. military personnel returning home after deployment. Psychol Med. 2012;42(8):1663–1673. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosellini AJ, et al. Predicting non-familial major physical violent crime perpetration in the US Army from administrative data. Psychol Med. 2016;46(2):303–316. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramesh D, et al. Prevalence of traumatic brain injury in cocaine-dependent research volunteers. Am J Addict. 2015;24(4):341–347. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein DJ, et al. Orbitofrontal cortical thinning and aggression in mild traumatic brain injury patients. Brain Behavior. 2016;6(12):e00581. doi: 10.1002/brb3.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coccaro EF, et al. Fronto-limbic morphometric abnormalities in Intermittenet Explosive Disorder and aggression. Biological Psychiatry: Clinical Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 2016;1(1):32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutgers DR, et al. White matter abnormalities in mild traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Am J Neuroradiology. 2008;29(3):514–519. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeter CB, et al. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of mild traumatic brain injury/concussion. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(8):657–670. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerr ZY, et al. Association between concussion and mental health in former collegiate athletes. Injury Epidemiology. 2014;1(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s40621-014-0028-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder as a disorder of impulsive aggression for DSM-5. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(6):577–588. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.First MB, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) New York: Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfohl B, et al. Structured interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorder: SIDP. Washington D.C: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coccaro EF, Nayyer H, McCloskey MS. Personality disorder-not otherwise specified evidence of validity and consideration for DSM-5. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2012;53(7):907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corrigan JD, Bogner J. Initial reliability and validity of the Ohio State University TBI identification method. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007;22(6):318–329. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000300227.67748.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coccaro EF, Berman ME, Kavoussi RJ. Assessment of life history of aggression: development and psychometric characteristics. Psychiatry Res. 1997;73(3):147–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63(3):452–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coccaro EF, Schmidt-Kaplan CA. Life history of impulsive behavior: Development and validation of a new questionnaire. J Psychiatric Research. 2012;46:346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patton J, Stanford M, Barratt E. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–74. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. IV. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Endicott J, et al. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29(2):321–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sorg MSF, Delano-Wood L, Luc MN, Schiehser DM, Hanson KL, Nation DA, Frank LR. White matter integrity in veterans with mild traumatic brain injury: associations with executive function and loss of consciousness. Journal of Head Trauma Rrehabilitation. 2014;29(1):21. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31828a1aa4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilde EA, Li X, Hunter JV, Narayana PA, Hasan K, Biekman B, Chu ZD. Loss of consciousness is related to white matter injury in mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2016;33(22):2000–2010. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tremblay RE. Early development of physical aggression and early risk factors for chronic physical aggression in humans. Curr Top Behav Neuroscience. 2014;17:315–327. doi: 10.1007/7854_2013_262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]