Dear editor,

Management of intra-oral infections in immunocompromised patients can be potentially challenging and deceiving [1]. Opportunistic pathogens including bacteria, viruses and fungi are the major cause of necrotising intra-oral infections in immunocompromised patients [2]. Overlapping clinical features produced by various infective agents acting alone or in combination may challenge clinical judgement at bedside. We present a case of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who developed Pseudomonas aeruginosa related necrotising ulcerative gingivitis.

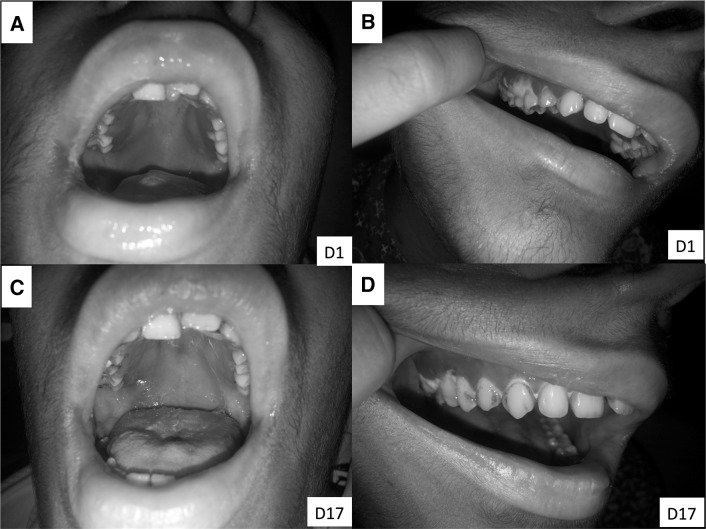

A 19-year-old girl, known case of AML, post allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) with graft failure was planned for second allogenic-HSCT. She presented on Day + 128 with fever and exquisite gingival pain in right maxillary pre-molar region of 1-day duration. She also complained difficulty in opening the mouth and pain on chewing food. Neither she had any such complaint in the past nor did she develop any such symptoms during high dose chemotherapy and HSCT. At presentation, she had fever (101.2 °F), tachycardia (112 beats/min) and tachypnea (26 breaths/min); her blood pressure was normal (114/72 mmHg). On oral cavity examination, generalised gingival erythema and edema was present (Fig. 1a) which was most conspicuous in right lateral maxillary region. A necrotic gingival plaque measuring 10 mm × 10 mm was present alongside the right upper premolar tooth (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

On day 1; generalized gingival erythema and edema (a), most conspicuous in right lateral maxillary region with a 10 mm necrotic plaque close to premolar tooth (b). On day 17; erythema and edema subsided, and healthy granulation tissue (c, d) replaced the necrotic slough

Investigations revealed Hemoglobin 94 g/L, total leucocyte count 0.3 × 109/L, absolute neutrophil count 0.1 × 109/L and platelet count 64 × 109/L. Peripheral smear was unremarkable for blasts/atypical cells. A panoramic dental radiograph was normal. Blood and urine cultures were sterile. On bacterial culture, swab from necrotic gingival plaque revealed growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on day 3 of admission. Fungal smear and culture were unremarkable.

Inj. Cefoperazone + sulbactam (2 g IV TDS) and Inj. Vancomycin (1 g IV BD) were empirically started with supportive measures (Fentanyl transdermal patch and morphine IV boluses for pain relief; 1% clotrimazole mouth paint and chlorhexidine mouth rinses). On day 3 of admission, in view of high grade fever and persistent pain, gram negative cover was escalated from Cefoperazone + sulbactam to Inj. Cefepime (2 g IV TDS) and Inj. Amikacin (750 mg IV OD). Vancomycin was stopped after sterile blood culture report.

She became afebrile by day 5 of admission. Gingival pain subsided completely by day 9. Gingival swab culture repeated on day 5 of admission was sterile. By day 17 of admission, necrotic gingival tissue got completely dislodged by underlying healthy granulation tissue (Fig. 1c, d). Cefepime and Amikacin were administered for a total of 3 weeks.

Intra-oral infections in immunocompromised patients result in substantial morbidity and mortality. These infections frequently lead to substantial pain and impaired feeding which in turn compromise tolerance and compliance to treatment especially in patients with haematological malignancies. It is well recognised that soft tissue infections in neutropenic patients have frequent association with little or no pus formation and favourably respond to prompt antimicrobial therapy. Clinical improvement in such infections has been reported to correlate with concurrent neutrophil count recovery. There is a limited role of operative management in view of risk of excessive bleeding due to concomitant thrombocytopenia and concerns regarding delayed healing [2, 3]. Maintenance of good oral hygiene and close adherence to neutropenic precautions have proven role in preventing such noxious infections [4]. Presence of dental caries and chemotherapy related transformation of oral flora are the important risk factors that favour development of destructive intra-oral infections after superinfection by pathogenic microorganisms [5]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa related bacteremia and necrotising soft tissue infections are known to portend a serious risk to severely neutropenic patients [6]. It is well-known that P. aeruginosa frequently inhabits oral cavities of immunocompromised patients. By virtue of its ubiquitous nosocomial existence, differentiation of P. aeruginosa infection from colonisation can be cumbersome [1]. The index case highlights some crucial learning points. Early isolation of P. aeruginosa in this severely neutropenic patient and prompt escalation to a combination of Cefipime and Amikacin proved worthy. Disappearance of P. aeruginosa on repeat swab and concurrent significant clinical improvement after starting combination of Cefipime and Amikacin reasonably speculates the role of P. aeruginosa as the perpetrator of gingivitis in this case. Gingival swab bacterial culture didn’t reveal growth of Porphyromonas, Prevotella or Fusobacterium—the microorganisms most often implicated in intra-oral infections [7]. Recently, the role of gram negative anaerobes belonging to phylum Synergistetes has been incriminated in necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis [8]. In view of severe neutropenia (due to underlying allograft failure) throughout the course of illness, it seems obvious that the combination antibiotic therapy played a major role in achieving a favourable outcome in this case. Despite no proven superiority of combination antibiotic therapy over monotherapy in P. aeruginosa infections, the decision to use a combination therapy in this case can be defended in view of anticipated prolonged neutropenia. Therefore, it shall be imperative to consider P. aeruginosa in the list of probable etiological agents causing intraoral infections in immunocompromised patients.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest between the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed signed written consent was taken from the patient involved.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Human and Animals Rights

No animals were involved in the study.

References

- 1.Enwonwu CO, Falkler WA, Idigbe EO. Oro-facial gangrene (noma/cancrum oris): pathogenetic mechanisms. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2000;11:159–171. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angel C, Patrick CC, Lobe T, et al. Management of anorectal/perineal infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in children with malignant diseases. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26(4):487–492. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(91)91001-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barasch A, Gordon S, Geist RY, et al. Necrotizing stomatitis: report of 3 Pseudomonas aeruginosa-positive patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96:136–140. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(03)00265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malhotra P, Varma S. Control of bacterial infection for effective treatment of oral mucositis. Lancet. 2002;360(9332):574–575. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09732-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamasaki Y, Satoh K, Nishiguchi M, et al. Acute oral complications in a pediatric patient with acute lymphoid leukemia. Pediatr Int. 2016;58:484–487. doi: 10.1111/ped.12829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatzinikolaou I, Abi-Said D, Bodey GP, et al. Recent experience with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia in patients with cancer: retrospective analysis of 245 episodes. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(4):501–509. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrera D, Alonso B, de Arriba L, et al. Acute periodontal lesions. Periodontol. 2000;65:149–177. doi: 10.1111/prd.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumgartner A, Thurnheer T, Lüthi-Schaller H, et al. The phylum Synergistetes in gingivitis and necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61(Pt 11):1600–1609. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.047456-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]