Abstract

Adult ocean sunfish are the heaviest living teleosts. They have no axial musculature or caudal fin. Propulsion is by unpaired dorsal and anal fins; a pseudocaudal fin (‘clavus’) acts as a rudder. Despite common perception, young sunfish are active predators that swim quickly, beating their vertical fins in unison to generate lift‐based propulsion and attain cruising speeds similar to salmon and marlin. Here we show that the thick subcutaneous layer (or ‘capsule’), already known to provide positive buoyancy, is also crucial to locomotion. It provides two compartments, one for dorsal fin musculature and one for anal fin muscles, separated by a thick, fibrous, elastic horizontal septum that is bound to the capsule itself, the roof of the skull and the dorsal surface of the short vertebral column. The compartments are braced sagittally by bony haemal and neural spines. Both fins are powered by white muscles distributed laterally and red muscles located medially. The anal fin muscles are mostly aligned dorso‐ventrally and have origins on the septum and haemal spines. Dorsal fin muscles vary in orientation; many have origins on the capsule above the skull and run near‐horizontally and some bipennate muscles have origins on both capsule and septum. Such bipennate muscle arrangements have not been described previously in fishes. Fin muscles have hinged tendons that pass through capsular channels and radial cartilages to insertions on fin rays. The capsule is gelatinous (89.8% water) with a collagen and elastin meshwork. Greasy in texture, calculations indicate capsular buoyancy is partly provided by lipid. Capsule, septum and tendons provide elastic structures likely to enhance muscle action and support fast cruising.

Keywords: dorsal and anal fins, horizontal septum, locomotion, Mola mola, ocean sunfish, red and white muscle, subcutaneous gelatinous capsule, tendons

Introduction

The ocean sunfish Mola mola (L.) (Tetraodontiformes: Molidae) is the heaviest (< 2.3 tonnes) living teleost fish and displays one of the most unusual morphologies of any vertebrate. A highly derived tetraodontiform species (related to puffer fish and boxfish), it is characterised by complete loss of the axial musculature, caudal and pelvic fins during development (Ryder, 1885; Gregory & Raven, 1934; Fraser‐Brunner, 1951; Santini & Tyler, 2002). Propelled by muscles of the (unpaired) dorsal and anal fins which function as lift‐generating wings (Watanabe & Sato, 2008), its vertebral column is short and rigid. The species has an evolutionarily novel rudder‐like tail structure described as a pseudocaudal fin or clavus (Fraser‐Brunner, 1951). The endoskeleton is largely cartilaginous (Cleland, 1862).

Mola is also noteworthy for the possession of a thick white layer beneath the skin that has been variously described as inflexible, rubbery, collagenous or (most recently) gelatinous (Watanabe & Sato, 2008). The material of this layer is positively buoyant in seawater, having a mean density of 1.015 g mL−1 (Watanabe & Sato, 2008). Its thickness increases in positive allometric fashion with body mass, so that the layer contributes 26% to total body mass in a 2‐kg sunfish and 44% in a 247‐kg individual (Watanabe & Sato, 2008).

Once thought to be slow‐moving surface‐dwelling fish that fed solely on gelatinous prey, sunfish are now known to be highly active fish that feed benthically on a variety of prey when young, chase fast‐moving prey in mid water, and are capable of substantial vertical (hundreds of metres) and horizontal (hundreds/thousands of km) migrations (Pope et al. 2010; Nakamura & Sato, 2014). Burst swimming speeds of 2.1 m s−1 (1 m TL fish) and 6.6 m s−1 (2 m TL fish) have been recorded (Nakamura & Sato, 2014; Thys et al. 2015), similar to values recorded for a variety of streamlined scombroid fish (Block et al. 1992). Sustained (cruising) swimming speeds are much lower (0.2–0.7 m s−1; Nakamura & Sato, 2014), but allow swimming rates of < 60 km day−1, comparable with cruising speeds of fish with axial musculature such as salmon and marlin (Pope et al. 2010).

Here we show that the musculo‐skeletal structure of Mola is far more complex than previously recognised, that the subcutaneous collagenous/gelatinous layer plays roles beyond simply providing the fish with neutral buoyancy. We also show that a fibrous horizontal septum plus long muscle tendons likely have significant roles in permitting the high swimming speeds recorded for the species.

Materials and methods

The sunfish studied (wet mass 17 kg, total length 0.67 m) was stranded live on the shores of Lough Foyle, N. Ireland, on 19 September 2014. It was stored at −20 °C until defrosted for dissection at Queen's University Belfast Marine Laboratory.

Dissection was carried out on 16–17 January 2017 and the procedure recorded from above by time‐lapse photography (Fujifilm X‐Pro2 camera; photo taken every 15 s; 2329 images). Initially the left‐hand side of the fish was dissected to determine structure and collect tissue (muscles, subcutaneous tissue, tendons) for histology. Next, the fish was turned over and muscles collected from the right‐hand side for determination of their mass. Subsamples (n = 3) of capsular collagenous/gelatinous tissue, dorsal and anal fin muscle types were collected for determination of water, salt and organic content (by drying in an oven at 60 °C to constant mass, then ashing in a furnace at 500 °C). Extra photography (still and video) was carried out throughout the dissection using Fujifilm X‐T1, Sony RX100, Nikon D5000 and Olympus TG‐4 cameras. During the preparation of published figures, to avoid confusion, all images were standardised in orientation so that the fish anterior was to the left of the image, the fish posterior to the right.

Histological samples (each approximately 5 mm long) were collected (n = 5) for capsular tissue and each muscle type. In addition, samples of tendon were taken from anal fin white muscles. Samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at 4 °C for 48 h, then stored in 70% ethanol until processing. These were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 7 μm. Staining was with haematoxylin and eosin. Sections were examined using a Leica ICC50HD microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH Wetzlar, Germany) 183 connected to a Dell workstation.

Results

Dissection

Subcutaneous collagenous/gelatinous tissue (‘capsule’)

When the thin, rough skin was removed, a brilliant white collagenous/gelatinous subcutaneous layer (hereafter named the ‘capsule’) was revealed (Fig. 1A). The capsular material varied in thickness, being about 6 cm thick in the region of the ventral keel (Fig. 1B) and about 3 cm thick anterior to the dorsal fin. Over most of the lateral surfaces, the capsule was about 2 cm thick, but was thinner (ca. 1 cm thick) over the visceral cavity. It > 0.5–1 cm over the surfaces of the skull and there were gaps at the eyes and spiracles. At the base of the dorsal/anal fins and clavus, the radial cartilages were firmly embedded in capsular material, as were the sheaths around tendons.

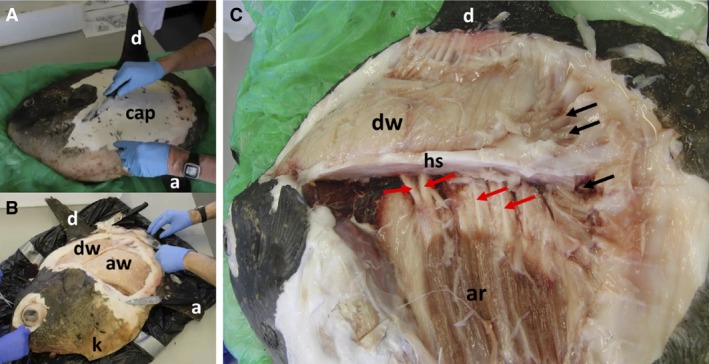

Figure 1.

Dissection of Mola mola. (A) Oblique view of fish from left‐hand side and from ventral aspect. Dorsal fin (d), anal fin (a), subcutaneous capsule (cap). (B) Oblique view of fish from anterior and ventral aspects, with capsule removed to reveal white muscles of dorsal (dw) and anal (aw) fins. The keel (k) is also labelled. (C) Lateral view of fish. Note that the image exhibits barrel distortion with head, medial fins and clavus curving away from the central part of the image. White anal fin muscles have been removed. Dorsal fin white muscles (dw), anal fin red muscles (ar), fibrous horizontal septum (hs). Black arrows indicate claval muscles; red arrows indicate haemal spines.

The capsular material was greasy and slippery to the touch. The capsule has been described as rubbery and having a function as armour (Gregory & Raven, 1934). We found that most of the capsule was stiff and relatively inflexible but had limited resistance to penetration by a knife or scalpel blade; it seemed unlikely that it could protect against large, sharp‐toothed predators such as sharks, seals or orcas. However, the capsule was far more rigid and resistant to cutting in areas at the bases of the fins and clavus, as well as in the thick keel.

Muscles and tendons

Vertebrate muscles are attached to structures at their two ends. By convention, the fixed proximal attachment is called the origin, and the mobile distal attachment (known as the insertion) moves with contraction. Following removal of the capsule, the lateral surfaces of the dorsal and anal fin musculature were revealed (Fig. 1B). The muscles were cream/white in colour and there was no sign of significant vascularisation. Dissection showed that almost all anal fin white muscles had broad origins on the ventral surfaces of a thick, tough, multilayered elastic fibrous sheet (horizontal septum, Fig. 1C; see also schematic Figs 7 and 8) that ran dorsal and lateral to the vertebral column (to which it was firmly bound by connective tissue) and was also firmly bound to the inner surfaces of the capsule. The horizontal septum therefore forms an elastic diaphragm between the dorsal and anal fin musculatures. It is non‐gelatinous and much more elastic than the capsule.

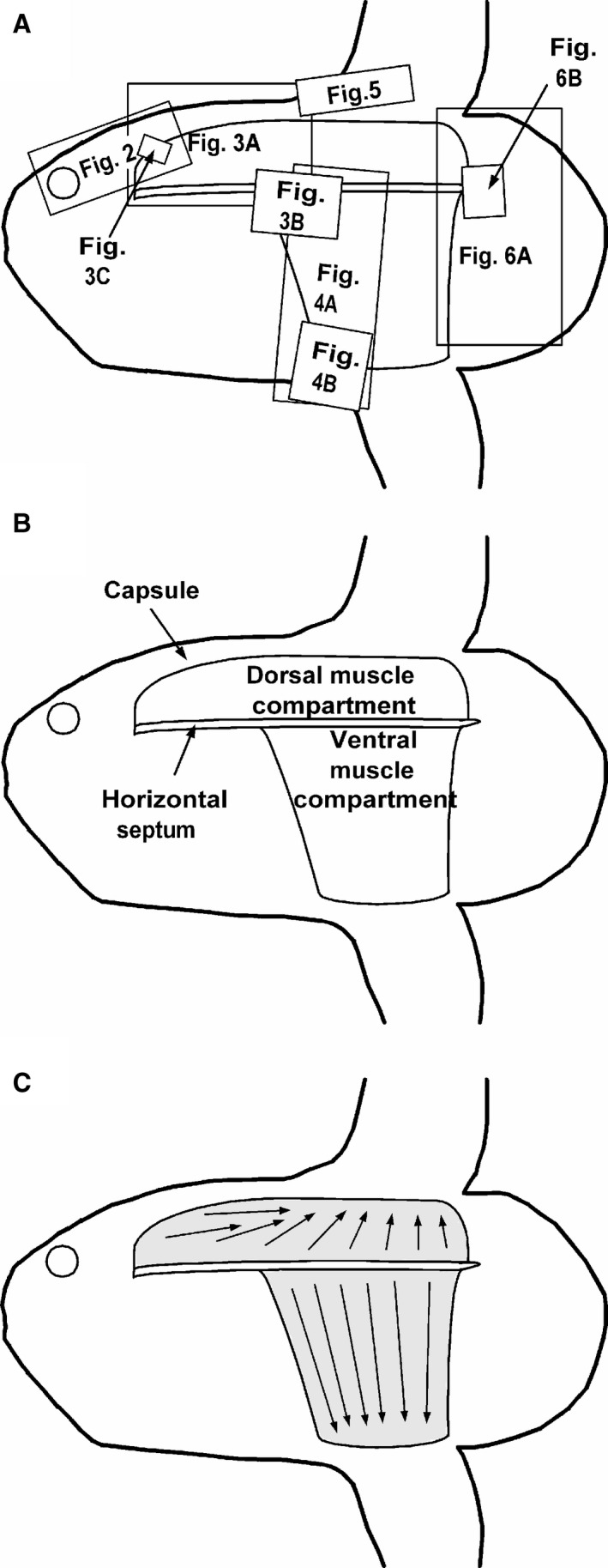

Figure 7.

Schematic diagrams of Mola mola from the side. (A) Locations of images displayed in Figs 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 superimposed upon an outline of a young sunfish. (B) Location of muscle compartments and horizontal septum. (C) Axes of muscle bellies in the two compartments. Head of arrows point towards tendons and their insertions on fin rays.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagrams of Mola mola locomotor system. (A) Lateral view to indicate location of origins of white muscles (yellow) and red muscles (red). (B) Transverse section through muscle compartments to indicate location of origins of white muscles (yellow), red muscles (red) and mixed red and white muscles (orange). (C) Transverse section through muscle compartments to indicate location of muscle blocks. Yellow indicates white muscle, red indicates red muscle, while orange indicates mixture of red and white muscles. (D) Simplified diagram of relationship between muscle, tendon, capsule, articular cartilage and dorsal fin ray from lateral aspect. (E) Simplified transverse section diagram of relationship between muscle bellies, tendons, capsule, articular cartilage and dorsal fin ray.

A small number of anal fin white muscles had origins on the interior surface of the capsule. The anal fin white muscles were inserted (via long tendons) onto processes at the proximal ends of the bony rays (lepidotrichia) of the anal fin. Manipulation of the muscles indicated that they were primarily inclinators that served to move the rays from side to side, though the more anterior muscles also served to elevate the anal fin. The white muscle origins occupied the full length and width of the ventral surface of the horizontal septum from the rear of the visceral cavity to the end of the vertebral column. Mainly, the muscle and tendons were directed dorso‐ventrally, though the anterior muscles were rather longer and directed caudally as well as dorso‐ventrally (Fig. 7C).

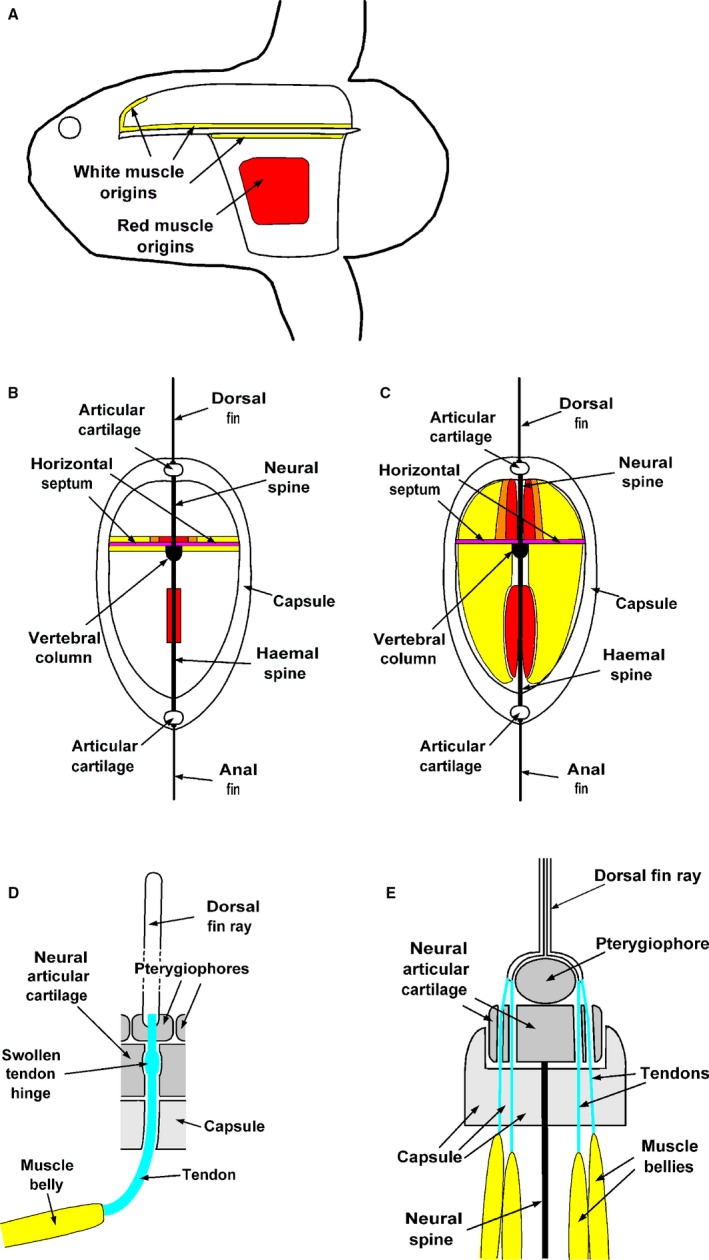

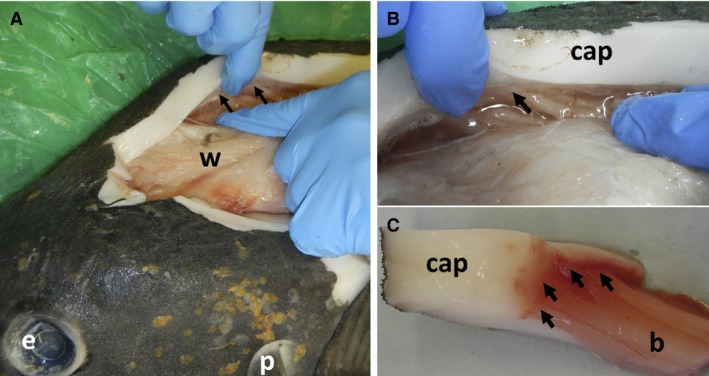

Many of the dorsal fin white muscles had origins on the dorsal surface of the horizontal septum, which surface ran anteriorly above the skull and acted as the floor to a chamber (semi‐circular section) in the capsule above the skull. Some of the white muscles had origins in the capsule, laterally and in the chamber above the skull (Figs 2 and 3; see also Fig. 8A,B). The white muscles were connected via tendons to the fin rays of the dorsal fin, but the length of the muscles and their orientation varied considerably. Posteriorly, the muscles and tendons were short and directed ventro‐dorsally. Anteriorly, many of the muscles were long and directed almost parallel with the vertebral column; their tendons curved through capsular channels and radial cartilages to meet the fin rays. Figure 3 illustrates the complexity of the dorsal fin white muscles. In some cases, at the anterior end of the dorsal chamber, multiple short white muscle bellies (bipennate muscles) were attached to shared tendons (Fig. 3A); those bellies had origins on both capsule and horizontal septum.

Figure 2.

Muscle origins on capsule of Mola mola. (A) View of muscle chamber above skull. White muscle (w), black arrows indicate position of origins. (B,C) Close‐ups of white muscle origins (arrowed). Capsule (cap), muscle belly (b). See Fig. 7A for positions of these images.

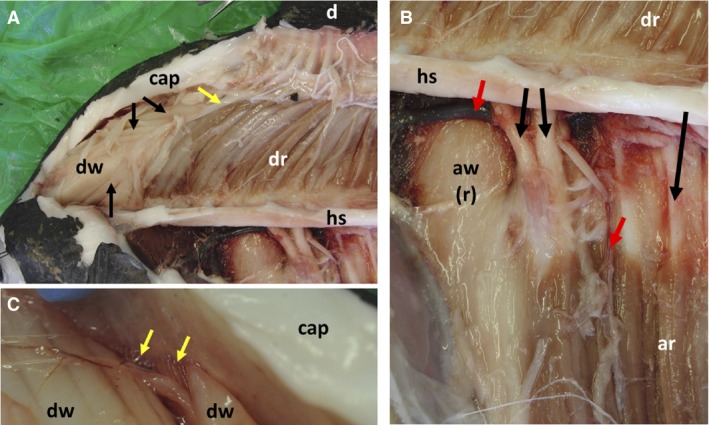

Figure 3.

Detail of arrangements of locomotory muscles of dorsal and anal fins of Mola mola. (A) Muscle chamber above skull (most dorsal fin white muscles removed). Dorsal fin (d), capsule (cap), dorsal fin white muscles (dw), dorsal fin red muscles (dr), horizontal septum (hs). Black arrows indicate separate white muscle bellies connected to a single tendon (indicated by yellow arrow), forming a bipennate muscle. (B) Close‐up of midsection of horizontal septum (hs), all white muscles removed from left side of fish. Dorsal fin red muscles (dr), anal fin red muscles (ar). Medial surface of anterior anal fin white muscles of right side of fish (aw(r)). Red arrows indicate blood vessels, black arrows indicate haemal spines. (C) Close‐up of dorsal fin muscle origins at anterior of muscle chamber. Red muscle origins (indicated by yellow arrows) are medial to those of dorsal fin white muscles (dw). See Fig. 7A for positions of these images.

Medial to the anal fin white muscles we found red muscles that were entirely separate from the white musculature and brown/red in colour (Fig. 1C); they were well vascularised with numerous arteries and veins visible. They had origins on the lateral surfaces of ventral bony projections (haemal spines) that linked the vertebral column with the anal fin radial cartilages. These were the only muscles driving the dorsal and anal fins that had origins on skeletal elements; all other origins were on the upper or lower surfaces of the horizontal septum or the inner surfaces of the capsule (Fig. 8A,B). The anal fin red muscles were much shorter than the overlying white muscles. Their insertions (via long tendons) were on the anal fin rays. The muscles were not connected either to the vertebral column or to the horizontal fibrous septum. As with the white muscles, they operated primarily as inclinators. All were directed dorso‐ventrally and were similar in length.

The dorsal fin white muscles also overlaid more medial, dark‐coloured red muscles (Fig. 3A). However, the dorsal fin red muscles had a different arrangement from that of the anal fin red muscles. They were more medially distributed than the white muscles that hid them, but their origins (on the horizontal septum and collagenous capsule) were similar in location to those of the overlying white muscles. Hence the red muscles varied greatly in length, being long and axially orientated anteriorly, short and ventro‐dorsally orientated at the posterior end of the fin; curving of muscles and tendons to connect with the fin rays was like that of the white muscles. The short red muscles that drive the posterior part of the dorsal fin were separate from the more lateral white muscles. However, the longer, more anterior red muscles were ‘pure’ medially, but showed some mixing with white muscles, before ‘pure’ white muscles were found laterally (Fig. 3A). Although neural vertebral spines ran from the vertebral column towards the radial cartilages of the dorsal fin bases, no muscles had origins on them. Red muscles of the dorsal fin were well vascularised.

Figures 4 and 5 show details of the tendons of the white muscles of the anal and dorsal fins respectively. From Fig. 4, it is evident that the anal fin white muscle tendons are very long, of similar length, and are held distally within sheaths that traverse the radial cartilages. The portions of the sheaths within the cartilages are swollen and pink in colour (Fig. 4B). Manipulation showed that the swollen sections could be bent easily, effectively acting as tendon hinges. Histological analysis was limited by freeze‐thaw damage, but it was clear that the swollen sections were characterised by thicker and well vascularised epitenons (outer connective tissue surrounding tendon bundles).

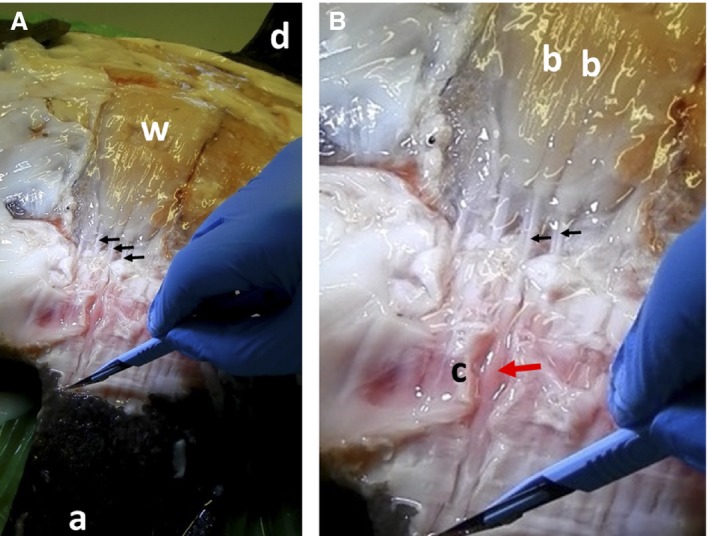

Figure 4.

Arrangement of anal fin white muscles and corresponding tendons of Mola mola. (A) Lateral view, capsular material mostly removed. Anal fin (a), dorsal fin (d), anal fin white muscle (w). Black arrows indicate tendons. (B) Close‐up of basal area of anal fin. Bellies of white muscles (b), haemal radial cartilage (c). Black arrows indicate tendons; red arrow indicates swollen portion of tendon sheath within cartilage; point of scalpel indicates distal part of tendon. See Fig. 7A for positions of these images.

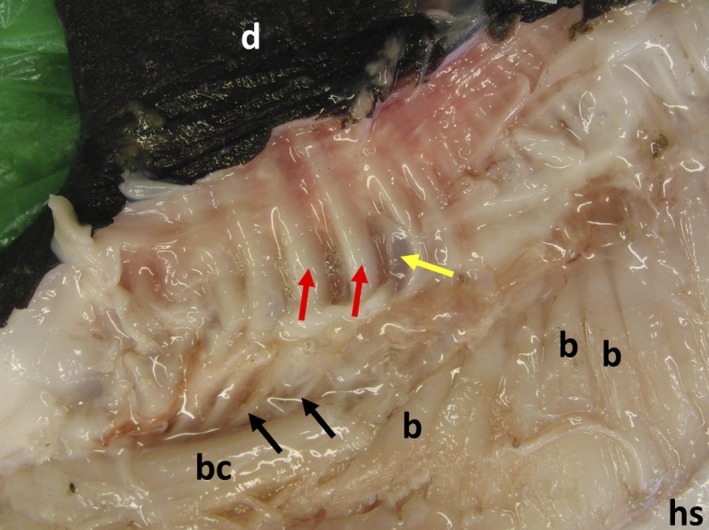

Figure 5.

Arrangement of dorsal fin white muscles and corresponding tendons of Mola mola: capsular material removed. Dorsal fin (d), horizontal septum (hs), bellies of white muscles with origins on horizontal septum (b), belly of white muscle with an origin on the capsule (bc). Black arrows indicate tendons, red arrows indicate tendon sheaths, yellow arrow indicates neural radial cartilage. See Fig. 7A for positions of these images.

Figure 5 demonstrates the complexity of the tendon arrangements of the dorsal fin white muscles. The tendons vary greatly in length and most curve dorsally in the capsule before entering the tendon sheaths and traversing the neural radial cartilages. Manipulation of the muscles and tendons of the dorsal and anal fins demonstrate that they could produce substantial lateral movements of the fins (i.e. acting as inclinators), as well as changes in fin shape by acting as elevators.

Figure 6 illustrates some of the muscles and tendons of the clavus. The muscles, buried in capsular material, are all short, red, and have origins close to one another on the rearmost part of the horizontal septum and/or the caudal end of the vertebral column. The matching tendons pass through cartilaginous material and cross a long, narrow ‘hinge’ of flexible connective tissue into the clavus itself, where they are attached to fin rays. Manipulation showed that the clavus acts as a simple rudder.

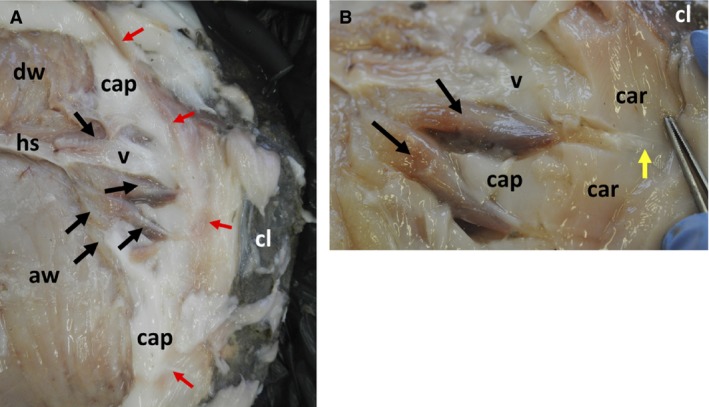

Figure 6.

Detail of arrangements of locomotory muscles of clavus of Mola mola. (A) View of rear of left‐hand side of fish, capsular material mostly removed. Dorsal fin white muscle (dw), anal fin white muscle (aw), horizontal septum (hs), capsule (cap), clavus (cl), caudal end of vertebral column (v). Black arrows indicate claval muscles; red arrows indicate position of soft ‘hinge’ of clavus. (B) Close‐up of two claval muscles (indicated by black arrows) and associated structures. Capsule (cap), clavus (cl), caudal end of vertebral column (v), cartilage (car). Yellow arrow indicates position of tendon; tip of forceps indicates position of hinge. See Fig. 7A for positions of these images.

Figures 7 and 8 are schematic diagrams that are designed to summarise and clarify the findings of the capsular, muscle and tendon dissections. Figure 7A shows the positions of the images shown in Figs 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 plotted on an outline image of a young sunfish. Figure 7B and C indicates the positions of muscle compartments and general directions of muscle bellies, respectively. Figure 8 consists of diagrams highlighting positions of muscle origins and muscle blocks, both from the lateral aspect and in transverse section, plus details of relations between muscle bellies, tendons, capsule, articular cartilages and dorsal fin rays.

Skeletal elements

There are numerous published images of museum skeletons of large Mola specimens (e.g. https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/108719778476213105/), and the skeleton of the dissected specimen was of similar appearance. Bony neural and haemal spines (the latter much longer than the former) connected the vertebral column (largely cartilaginous) to the dorsal and anal fin radial cartilages, respectively. The spines were reinforced in the sagittal plane by very thin ellipsoidal bony plates that served to separate blocks of muscles on either side of the body.

Figure 9 shows the structure of the bases of the dorsal and anal fins. The fin ray count (dorsal fin, 18; anal fin 17) was slightly lower than reported by Anderson & Cupka (1973) (dorsal fin, 19; anal fin 18). The cartilage pads (pterygiophores) that support the fin rays of both fins varied in width, being broad anteriorly, becoming wider until about halfway along the fin and becoming smaller posteriorly. The fin bases consequently have hydrofoil rather than flat plate sections; manipulation of the muscle tendons demonstrated that the hydrofoil camber could be altered greatly during flapping. It is also evident from this figure that the sections of the two fins and the shapes of their pterygiophores were dissimilar, implying asymmetrical hydrodynamic characteristics.

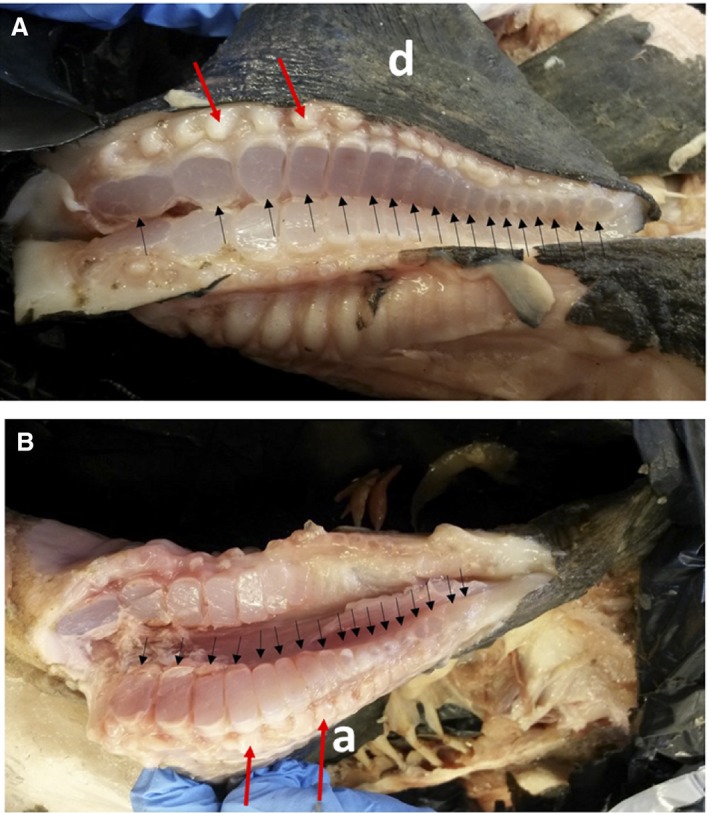

Figure 9.

Cut bases of propulsive dorsal (A) and anal (B) fins of Mola mola. Dorsal fin (d), anal fin (a). Black arrows indicate cut cartilaginous pads (pterygiophores) that support fin rays (lepidotrichia). Red arrows indicate lateral processes at bases of lepidotrichia (to which tendons are attached).

Histology

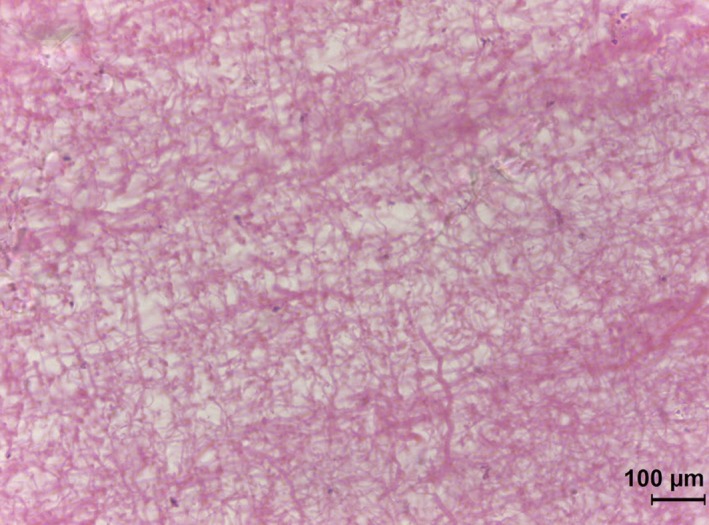

The muscle and tendon samples showed extensive freeze–thaw damage (cf. Kaale & Eikevik, 2013). However, it could be observed that vascularisation of the perimysium (layers between muscle bundles) was richest in the claval muscles and the vertical fin red muscles, but sparsest in the vertical fin white muscles. The capsular material was almost free of vascularisation; it had a homogeneous appearance with no directionality or layering (Fig. 10). There were two categories of fibres distributed in an open meshwork. The thicker ones were collagenous, the thinner composed of elastin. There was no sign of structure within the matrix. In particular, there was no evidence of adipose tissue or oil globules.

Figure 10.

Section of subcutaneous capsular material. Note meshwork of thick (collagen) and thin (elastin) fibres. Note also the absence of blood vessels and lipid globules.

Tissue composition

Sunfish tissue water contents are displayed in Table 1 and compared with data for the lumpfish Cyclopterus lumpus (Davenport & Kjørsvik, 1986), another oceanic fish of demersal ancestry that has a thick gelatinous subcutaneous layer that aids in the attainment of neutral buoyancy and acts as an exoskeleton. These data show that the subcutaneous tissue of the capsule has similar water content (90%) to that of female lumpfish subcutaneous tissue (93%), rather lower than the 96.5% of gelatinous tissues of deep‐sea snail fish (Gerringer et al. 2017) and the 95–98% of neutrally‐buoyant gelatinous invertebrates such as medusae (Doyle et al. 2007). However, the water content is higher than that of the sunfish fin muscles (79–84%). The salt content (23% of dry mass) is low by comparison with known jellyfish prey (Doyle et al. 2007); this presumably reflects the low osmolarity of body fluids of teleosts by comparison with marine invertebrates. Most (77%) of the dry mass is made up of organic matter (Table 2).

Table 1.

Water content of tissues of Mola mola (this study) and Cyclopterus lumpus (Davenport & Kjørsvik, 1986)

| Tissue type | Water content (mean % by mass, n = 3, SD in parentheses) |

|---|---|

| Mola mola | |

| Dorsal fin white muscle | 83.5 (3.6) |

| Dorsal fin red muscle | 80.3 (0.2) |

| Anal fin white muscle | 82.2 (1.1) |

| Anal fin red muscle | 79.4 (1.0) |

| Subcutaneous collagenous/gelatinous tissue | 89.8 (1.1) |

| Cyclopterus lumpus | |

| Female | |

| Axial white muscle | 86 |

| Subcutaneous gelatinous tissue | 93 |

| Male | |

| Axial white muscle | 64 |

| Subcutaneous gelatinous tissue | 89 |

Table 2.

Composition of subcutaneous capsule of Mola mola

| Mean (n = 3) | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Water content as % wet mass | 89.8 | 1.1 |

| Salt content as % dry mass | 23.4 | 4.5 |

| Organic content as % dry mass | 76.6 | 4.5 |

| Salt content as % wet mass | 2.4 | 0.7 |

| Organic content as % wet mass | 7.8 | 0.6 |

Discussion

Ocean sunfish exhibit the most extreme known form of tetraodontiform locomotion. Although all tetraodontid fish (including pufferfish and boxfish) employ the dorsal and anal fins as propulsors, in most cases these are supplemented by the action of other fins; they are median and paired fin (MPF) swimmers. For example, Gordon et al. (1996) showed that pufferfish combine in‐phase use of the dorsal and anal fins with out‐of phase pectoral fin propulsion. During burst swimming they even recruit the caudal fin (used as a rudder at lower speeds) to provide additional propulsive force. The puffer body shape is variable and a degree of posterior body undulation occurs at high speed. In the ocean sunfish the caudal fin is absent, the body entirely rigid and the pectoral fins very small; although they are undoubtedly of use in low speed manoeuvring, they can make little contribution to cruising or burst swimming. Effectively rectilinear propulsion depends on two median fins alone.

Capsular exoskeleton

From our study it is evident that the thick, white, homogeneous subcutaneous ‘capsule’ plays a substantial exoskeletal role. First, it provides a stiff, streamlined, non‐undulatory body shape that presumably has a low drag coefficient and avoids the high drag costs of undulation (cf. Weihs, 1974; Webb, 1975). The combination of a thin rough skin and a thick underlying capsule differs markedly from the thin, complex, collagenous fabric that surrounds the axial musculature of undulatory teleosts and transmits axial muscular force to a flexible vertebral column (Hebrank, 1982). Secondly, the capsule forms two chambers (separated by the thick, fibrous, horizontal septum, robustly connected to the capsule on either side; Figs 7B and 8A–C) that contain the muscles that drive the tall dorsal and anal fins. Thirdly, it provides secure anchorages for the dorsal and anal fin radial cartilages that are embedded within in it. These cartilages are braced apart by the neural and haemal spines, themselves bound by fibrous tissue to the vertebral column, so that the capsule and endoskeleton are interdependent. Fourthly, it provides origins for many of the dorsal fin red and white muscles and a few of the anal fin white muscles. Finally, it provides channels that guide and hold the muscle tendons that link muscles to fin rays; this is particularly important in the case of the anterior dorsal fin musculature, where the channels are curved to permit the tendons to transfer the direction of muscle action to the fin rays.

The material of the capsule is known to be less dense (density 1.015 g mL−1) than seawater (density 1.033 g mL−1) (Watanabe & Sato, 2008); our finding that water content is 90% by mass, derived from a stranded fish that might conceivably have been dehydrated, indicates that it is gelatinous (as well as collagenous) but less watery than in a range of deep‐water teleosts (96.5%; Gerringer et al. 2017). Histologically, the observed meshwork of collagen and elastin indicates that protein makes up some of the organic content of the capsule. Protein has a density of about 1.35 g mL−1 (Fischer et al. 2004), substantially denser than seawater. Lipids of various sorts, some intracellular, some extracellular, have often been implicated in buoyancy provision in fish (see review of Phleger, 1998), but there were no signs of lipid globules histologically. More study, including appropriate biochemical analysis, is required to further elucidate the low density of Mola capsular material identified by Watanabe & Sato (2008). However, our qualitative observation that the capsule material is greasy suggests that lipids may be present.

Muscles and tendons

Our dissection revealed numerous differences in muscle arrangements from the images shown in Gregory & Raven (1934). Particularly, it showed that the thick, fibrous horizontal septum (undescribed in their study) is crucial, carrying the origins of almost all anal fin white muscles and most of the dorsal fin muscles (Fig 8), as their origins are not on the vertebral column itself. The horizontal septum clearly has a substantial role in force transmission and has the potential for energy storage.

Gregory & Raven (1934) indicated that the dorsal and anal fin muscles were a mixture of erectors and depressors. In ‘conventional’ teleosts, each vertical fin ray is moved by three pairs of muscles. First, there are erectors and depressors that respectively raise and lower the fin rays in the medial plane. Secondly, there are inclinators that move the fin rays from side to side (Videler, 1993). In Mola, the dorsal and anal fin muscles are essentially inclinators that flap the fin rays from side to side, although also serving to maintain the fins erect and maximise web area.

The medial positioning of Mola red vertical fin muscles implies that they will exert less force on the fin rays than will the more lateral white muscles, as they are more closely aligned with the axes of the fin rays than are the white muscles (cf. tuna red muscles: Syme & Shadwick, 2011). However, as red muscles are employed primarily in cruising, this layout is appropriate.

A novel finding was that the supracranial chamber of the capsule contained bipennate white muscles (i.e. muscles in which multiple muscle bellies are connected at an angle to a single tendon) that acted on fin rays in the anterior part of the dorsal fin; they were not present in the anal fin musculature. The bipennate muscles had origins on the capsule and horizontal septum. When pennate muscles contract and shorten, their pennate angle increases, transferring force to the tendon. Pennate muscles are known from terrestrial vertebrates (particularly mammals) and are also found in the chelipeds of crabs. These types of muscles generally allow higher force production, but a smaller range of movement (Martini & Ober, 2006). Alexander (1979) demonstrated (for crab claws), that the bipennate arrangement allowed more powerful muscles to be packed into smaller spaces than is the case for conventional muscles in which the muscle fibres and tendons are parallel. As far as we are aware, a bipennate muscle arrangement has not been described previously in fish.

Watanabe & Sato (2008) found that dorsal fin muscles and anal fin muscles of Mola were of similar mass over a wide range of body size and suggested that the two fins were flapped by similar levels of muscle power. They recognised that the muscles had very different morphologies, but not that this has implications for power generation – the relation between muscle mass, length, cross‐sectional area and angle in relation to power is complex and at present it cannot be assumed that power supplied to both fins is equal.

A feature of all anal and dorsal fin muscles of Mola is that their force is transmitted distally to the fin rays by long tendons. Fish tendons have been extensively studied, but only in terms of axial musculature. Gemballa et al. (2003) reported on the evolution of gnathostome myoseptal tendons, demonstrating their great antiquity (400 million years), and the characteristics of tuna tendons were studied experimentally by Shadwick et al. (2002). Long tendons have been repeatedly associated with spring‐like elastic storage of energy in terrestrial mammals, in which they allow great enhancement of muscle action and economy (e.g. Alexander & Vernon, 1975; Biewener, 1998; Biewener et al. 1998). However, this requires significant strain (stretching) of the tendons. In tuna, Shadwick et al. (2002) showed (in vivo) that strain did not occur, even during burst swimming; the tendons simply transferred force from muscles to the oscillatory caudal peduncle, even though tendon structure was like that of mammals. Here we have demonstrated that the Mola fin muscle tendons also incorporate hinges (located within the articular cartilages), which opens up the possibility that tendons distal to the hinge behave differently from the tendons proximal to the hinge.

In addition, it has been recognised since the late 20th century that connective tissue sheets (e.g. horizontal septum), muscles and tendons are all elastic structures that have the potential to store and exchange energy (Roberts & Azizi, 2011). It seems very likely that the septum‐muscle–tendon combination of Mola enhances the forces generated by muscle contractions, but experiments upon live fish and/or freshly excised material would be needed to confirm this.

Synthesis

The primary role of unpaired dorsal and anal fins of primitive undulating teleosts was once assumed to lie solely in providing stability against roll and yaw, but Flammang et al. (2011) demonstrated that they provided thrust, too, augmenting that developed by the oscillating caudal fin, with the dorsal fin contributing more thrust than the anal fin. In tail‐less Mola, almost all thrust is generated by the median anal and dorsal fins, although the pectoral fins may play a role at low speeds.

Our study has demonstrated that the unpaired fins have pronounced differences in the arrangement of their muscles, muscle origins and tendon arrangements. That the axis of delivery of muscle force to the fins is at near‐right angles to the body axis in Mola has long been known (e.g. Ryder, 1885; Gregory & Raven, 1934), but the great differences in the anatomical arrangements involved in achieving this have not previously been described in detail. Particularly interesting is the role of the horizontal septum. This thick, multi‐layered, fibrous sheet carries the origins of white muscles of both fins. This suggests that efficient fast swimming will have to involve simultaneous contraction of the two sets of muscles if they are not to interfere with each other. The situation is different for the red muscles. Anal fin red muscles have no connection with the horizontal septum, whereas many dorsal fin red muscles do. This will facilitate independent fin action at low speeds.

It is also evident that the thick subcutaneous skin capsule is crucial to the locomotory function of the sunfish, its role being far more complex than simply providing buoyancy. The current study was carried out on frozen material; a detailed study of the capsular material of fresh specimens would be valuable. Similarly, Watanabe & Sato (2008) demonstrated great allometric changes in capsular thickness, median fin size and aspect ratio during growth. It is likely that the role and composition of the capsule will also vary over the wide size range of this highly derived teleost.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

The study was initially planned jointly by J.D., N.P. and J.H. The dissection was carried out by J.D., N.P. and L.E. L.E. provided photographic and IT support, and E.C. conducted all histology; both provided appropriate text. All authors contributed to preparation and finalisation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The Fisheries Society of the British Isles (FSBI) funded a PhD studentship held by N.P. The FSBI also awarded an Alwyn Wheeler travel award to J.D. Additional support funding was provided by Queens University Belfast through the G & M Williams Fund. We would also like to thank the Loughs Agency for supplying the stranded sunfish used in this study. We are grateful for the constructive criticism of two anonymous reviewers that has significantly improved the manuscript.

References

- Alexander RM (1979) The Invertebrates. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RM, Vernon A (1975) The mechanics of hopping by kangaroos (Macropodidae). J Zool 177, 265–303. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WD Jr, Cupka DM (1973) Records of the ocean sunfish, Mola mola, from the beaches of South Carolina and adjacent waters. Chesapeake Sci 14, 295–298. [Google Scholar]

- Biewener AA (1998) Muscle function in vivo: a comparison of muscles used for elastic energy savings versus muscles used to generate mechanical power. Am Zool 38, 703–717. [Google Scholar]

- Biewener AA, Konieczynski D, Baudinette RV (1998) In vivo muscle force–length behavior during steady‐speed hopping in tammar wallabies. J Exp Biol 201, 1681–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block BA, Booth D, Carey FG (1992) Direct measurement of swimming speed and depth of blue marlin. J Exp Biol 166, 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J (1862) On the anatomy of the short sunfish (Orthragoriscus mola). Nat Hist Rev (Lond) 2, 170–185. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport J, Kjørsvik E (1986) Buoyancy in the lumpsucker Cyclopterus lumpus (L.). J Mar Biol Assoc UK 66, 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle TK, Houghton JDR, McDevitt R, et al. (2007) The energy density of jellyfish: estimates from bomb‐calorimetry and proximate‐composition. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 343, 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H, Polikarpov I, Craievich AF (2004) Average protein density is a molecular‐weight‐dependent function. Protein Sci 13, 2825–2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flammang BE, Lauder GV, Troolin DR, et al. (2011) Volumetric imaging of fish locomotion. Biol Lett 7, 695–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser‐Brunner A (1951) The ocean sunfishes (Family Molidae). Bull Br Mus (Nat Hist) Zool 1, 87–121. [Google Scholar]

- Gemballa S, Ebmeyer L, Hagen K, et al. (2003) Evolutionary transformations of myoseptal tendons in gnathostomes. Proc Biol Sci 270, 1229–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerringer ME, Drazen JC, Linley TD, et al. (2017) Distribution, composition and functions of gelatinous tissues in deep‐sea fishes. R Soc Open Sci 4, 171063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MS, Plaut I, Kim D (1996) How puffers (Teleostei: Tetraodontidae) swim. J Fish Biol 49, 319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory WK, Raven HC (1934) Notes on the anatomy and relationships of the ocean sunfish (Mola mola). Copeia 1934, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hebrank MR (1982) Mechanical properties of fish backbones in lateral bending and in tension. J Biomech 15, 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaale LD, Eikevik TM (2013) A histological study of the microstructure sizes of the red and white muscles of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) fillets during superchilling process and storage. J Food Eng 114, 242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Martini F, Ober WC (2006) Fundamentals of Anatomy and Physiology. London: Pearson Educational. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura I, Sato K (2014) Ontogenetic shift in foraging habit of ocean sunfish Mola mola from dietary and behavioral studies. Mar Biol 161, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Phleger CF (1998) Buoyancy in marine fishes: direct and indirect role of lipids. Am Zool 38, 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Pope EC, Hays GC, Thys TM, et al. (2010) The biology and ecology of the ocean sunfish Mola mola: a review of current knowledge and future research perspectives. Rev Fish Biol Fish 20, 471–487. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TJ, Azizi E (2011) Flexible mechanisms: the diverse roles of biological springs in vertebrate movement. J Exp Biol 214, 353–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder JA (1885) The swimming‐habits of the sunfish. Science 6, 103–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini F, Tyler JC (2002) Phylogeny of the ocean sunfishes (Molidae, Tetraodontiformes), a highly derived group of teleost fishes. Ital J Zool 69, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shadwick RE, Rapoport HS, Fenger JM (2002) Structure and function of tuna tail tendons. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 133, 1109–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme DA, Shadwick RE (2011) Red muscle function in stiff‐bodied swimmers: there and almost back again. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366, 1507–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thys TM, Ryan JP, Dewar H, et al. (2015) Ecology of the Ocean Sunfish, Mola mola, in the southern California Current System. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 471, 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Videler JJ (1993) Fish Swimming. The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Sato K (2008) Functional dorsoventral symmetry in relation to lift‐based swimming in the ocean sunfish Mola mola . PLoS ONE 3, e3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb PW (1975) Hydrodynamics and energetics of fish propulsion. Bull Fish Res Board Can 190, 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Weihs D (1974) Energetic advantages of burst swimming of fish. J Theor Biol 48, 215–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illustration of the skeleton of the Mola mola (Mola rotunda), the ocean sunfish, 1898. https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/108719778476213105/ (last accessed 30‐3‐2018).