Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes (LM) is an opportunistic pathogen, and the most common central nervous system manifestation is meningitis while listerial brain abscesses are rare. We describe 2 cases of brain abscess due to LM and a literature review. Only 73 cases were reported in the literature from 1968 to 2017. The mean age was 51.9, and the mortality rate was 27.3%. In 19% of cases, no risk factors for neurolisteriosis were identified. Blood cultures were positive in 79.5% while CSF or brain abscess biopsy material was positive in 50.8%. In 40% was started a monotherapy regimen while in 60% a combination therapy without substantial differences in mortality. Fifty-two percent underwent neurosurgery while 45.3% has been treated only with medical therapy. The mortality rates were, respectively, 13% and 38.2%. Only 25% of patients who were treated for ≤6 weeks underwent neurosurgery, while 80% of those who were treated for ≥8 weeks were operated. The mortality rates were, respectively, 12.5% and 0%, suggesting that a combined approach of surgery and prolonged medical therapy would have an impact on mortality. We believe that it is essential to carry out this review as brain abscesses are rare, and there are no definitive indications on the optimal management, type, and duration of therapy.

1. Introduction

Listeria monocytogenes (LM) is a facultative intracellular Gram-positive bacillus, widely distributed in nature and therefore found in multiple ecological sites, which can cause listeriosis, a serious foodborne bacterial infection [1]. Invasive listeriosis is classified into three forms: bacteraemia, neurolisteriosis, and maternal-neonatal infection. The incidence of listeriosis in the western hemisphere is estimated to be approximately three to six cases per 1 million population per year [2]. Epidemiological studies have identified host risk factors for bacteraemia and neurolisteriosis which include old age, innate and cellular immune deficiencies, cancer, HIV infection, cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, and immunosuppressive therapies [3–6]. The most common central nervous system manifestation is meningitidis, while meningoencephalitis, rhombencephalitis, and cerebritis are less common [7]. Brain abscesses are extremely rare as they account for approximately 1–10% of CNS listerial infections and are observed in 1% of all listerial infections [8]. There are unresolved issues regarding surgical drainage of the abscess, selection of antibiotic regimen, and optimal treatment duration. We describe two cases (the first without evident immunodeficiency and the second affected by bullous pemphigoid) of brain abscess due to Listeria monocytogenes and discuss them by reviewing the literature on this topic.

2. Case Report

2.1. Case 1

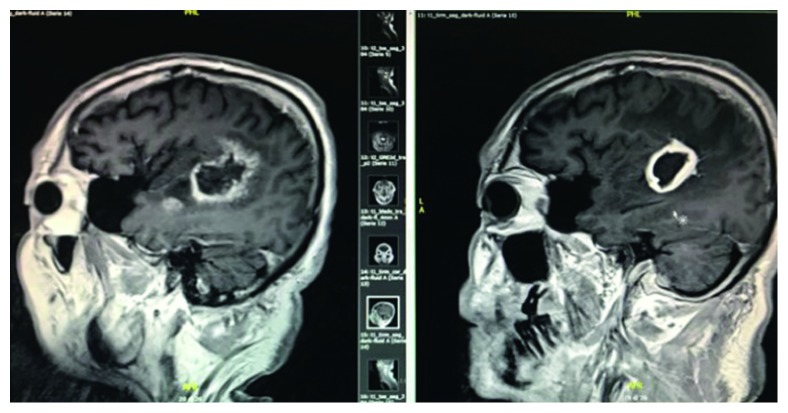

A 62-year-old immunocompetent man with no significant previous medical history was hospitalized for high-grade fever, intractable hiccup, and interscapular pain. On admission, his white blood cell count was 11 × 109/L (normal range 4.50–10.80 103 mmc), his C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated at 4.30 mg/dl (normal range 0.00–0.75 mg/dl), while his chest radiograph, abdomen ultrasound, and echocardiography were normal. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain revealed a diffuse abnormal pattern (presence of aspecific inflammatory material) with hypodense lesions located in the trigonum of lateral ventricle in an underlying condition of demyelination and gliosis, suspicious for chronic ischemic vascular disease. A broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and ceftriaxone was initiated. The patient became afebrile within a few days. A neurological examination found him to be alert and oriented, and he did not have a stiff neck. However, the patient had persistent hiccups and headache. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed enhancement of both trigeminal nerves and white spot lesions on the pons, cerebral peduncle, midbrain, and thalamus. He was then transferred to the Neurology Department where a lumbar puncture was carried out. His cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was clear, WBC count was 50 cells/µl, 100% lymphocytes, normal glucose level (normal range 40–70 mg/dl), 103 mg/dl protein (normal range 15–45 mg/dl), and the CSF culture was negative. As a viral etiology was suspected, antibiotic therapy with vancomycin + ceftriaxone was discontinued and treatment with acyclovir and steroid was initiated. After 72 hours, a progressive deterioration of his clinical-neurological condition occurred: he became hyperpyretic and aphasic and Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) was 9. CT brain imaging showed the involvement of the subcortical left temporoparietal lobe, and he was then transferred to the Infectious Disease Department. Blood cultures were performed, and another lumbar puncture was carried out. A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed cloudy CSF with increased spinal column pressure, granulocytic pleocytosis (180 cells/µl, with PMN 90%), normoglychorrachia, and 145 mg/dl spinal fluid protein. A combination antimicrobial therapy with ampicillin 3 g/6 h + gentamicin 80 mg/8 h was initiated; 72 hours later, fever and other systemic signs and symptoms disappeared resulting in complete recovery (GCS15). Listeria monocytogenes were isolated from the patient's blood and recognized from CSF using the molecular technique (Multiplex Real-Time PCR Meningitis/Encephalitis Filmarray bioMerieux). The patient was treated with intravenous ampicillin for 4 weeks, with combination intravenous gentamicin for the initial 2 weeks and switched to oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160/800 mg/8 h for 1 month. An MRI was repeated after 8 weeks of antibiotic therapy due to the persistence of fluent aphasia. MR imaging showed a ring-enhancing lesion in the left fronto-temporoparietal lobe, consistent with a brain abscess with significant perilesional edema (Figure 1). Surgical excision of the lesion was performed. Molecular identification of the pus using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) identified DNA of Listeria monocytogenes. The patient was represcribed intravenous ampicillin + gentamicin for 4 weeks, and therapy was then switched to oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160/800 mg/12 h for further 4 weeks. Patient's condition has improved progressively and with a complete recovery of linguistic abilities.

Figure 1.

MR image showing the evolution of the ring-enhancing lesion in the left fronto-temporoparietal lobe in a brain abscess with significant perilesional edema.

2.2. Case 2

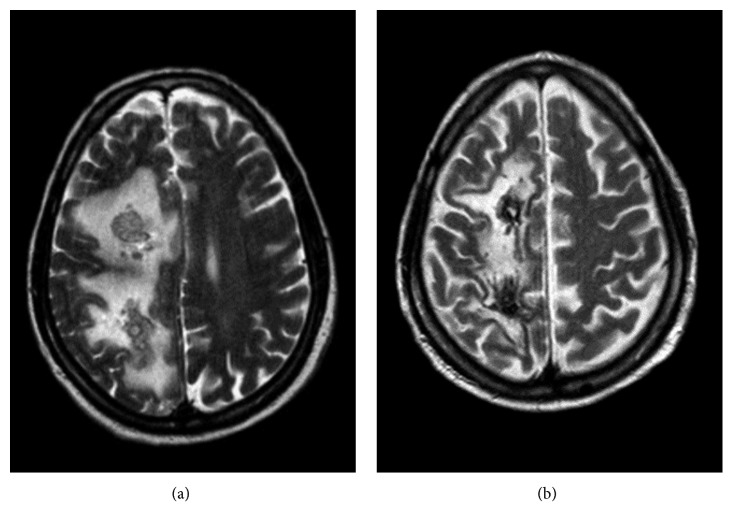

A 72-year-old man with a history of bullous pemphigoid treated with a monoclonal antibody was admitted to another hospital due to a balance disorder. A neurological examination identified a left hemiplegia with no sensory deficits. An immediate CT brain scan showed a ring-enhancing cortical-subcortical lesion on the right frontal-parietal hemisphere. In view of the CT scan findings, gadolinium MRI of the brain was performed. MRI showed a caudal extension of the lesion with irregular enhancement and a necrotic region (Figure 2). Blood cultures were collected before initiating antimicrobial therapy. A few days later, his blood cultures grew Listeria monocytogenes. Based on organism sensitivity, intravenous therapy with ampicillin 3 g/6 h + gentamicin 80 mg/8 h + vancomycin 1 g/12 h was initiated. Steroid therapy was also administered due to the associated moderate mass effect. The patient was then transferred to our Infectious Diseases Department for further workup and management. Forty-eight hours after the initiation of target therapy, the patient was afebrile. Twenty days later, he showed progressive clinical and neurologic deterioration characterized by visual hallucinations, frontal symptoms with disinhibition, and persistent hemiplegia. An MRI brain scan showed a substantial increase in lesion size, and new lesions appeared on splenium of corpus callosum and right temporal lobe with a significant mass effect on the right lateral ventricle. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160/800 mg/8 h was added. The patient underwent a surgical biopsy of the lesion. Molecular identification of the brain tissue using PCR identified Listeria monocytogenes DNA. At the follow-up appointment five weeks later, additional imaging studies were performed which showed a considerable reduction in the size and enhancement of the lesions. Ampicillin, gentamicin, and vancomycin therapy was stopped while trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole therapy was continued. The patient's neurological condition improved. An MRI brain scan performed after 8 weeks of antibiotic therapy, showed significant improvement, with noticeable decrease in the amount of vasogenic edema. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole therapy was discontinued, and the patient was discharged. A year after the listeria brain abscess diagnosis, the patient does not show any significant neurologic deficits and is able to carry out all activities of daily living.

Figure 2.

MR image showing a caudal extension of the lesion with irregular enhancement with irregular enhancement and a necrotic region (FLAIR/long TR).

3. Discussion

Listeria monocytogenes can invade tissues that are normally resistant to infection, such as the CNS, a gravid uterus, or a fetus. This bacterium reaches the CNS due to hematogenous spread from the gastrointestinal tract [9]. The epithelium of the choroid plexus enables LM to gain access to CNS and causes a meningitides infection. On the other hand, LM may reach the brain parenchyma via the cerebral capillary endothelium, a single layer of brain microvascular endothelial cells characterized by tight junctions. It has been reported that LM-infected macrophages may pass through endothelial cells via the middle cerebral artery resulting in cerebritis which leads to brain abscess formation [10–13].

Furthermore, LM can use a peripheral intraneural route to invade the CNS. A recent animal study suggests that once the bacteria have gained access to the CNS via the peripheral nervous system, the infection can spread along the axons, producing additional lesions by traveling within the axons of the trigeminal nerve [14–16]. According to Bojanowski et al., once inside the CNS, the bacterium may travel along the white fiber tracts of the brain, resulting in a distinct anatomical imaging thus enabling early diagnosis [17]. The spreading of multiple listeria brain abscess within the cerebral nervous system through the intrassonal pathway justified their specific pattern and why they have more detrimental effects than bacterial brain abscess. In our case 1, MRI shows that the spreading follows the arcuate fasciculus. In case 2, the caudal extension of the lesions may also suggest that the lesion follows the projection fiber tracts.

Brain abscesses are extremely rare, accounting for approximately 1–10% of CNS listerial infections. These abscesses are generally located in the subcortical grey matter, especially in the thalamus and basal ganglia [18, 19]. Protection against LM is predominantly cell-mediated. Individuals with impaired cell-mediated immunity are at risk of developing listerial infections [20].

To the best of our knowledge, only 73 cases of brain abscess caused by L. monocytogenes were reported in the literature between 1968 and 2017. We report further two cases (Table 1) [1, 13, 17, 21–23].

Table 1.

Seventy-three cases of brain abscess caused by Listeria monocytogenes reported in the literature between 1968 and 2017 (we described two other cases).

| N. | Age/sex | Underlying diseases | Blood | CSF/brain abscess | Surgery/type | Antibiotic | Duration of therapy | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70/M | Myasthenia gravis in immunosuppressive TP | + | − | ND | Ampicillin + gentamicin; trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 6 weeks ampicillin + gentamicin for 10 days trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole | Survived | Chalouhi et al., 2013 |

| 2 | 57/F | Cirrhosis; DM | + | + | Biopsy | Ampicillin + gentamicin | NR | Died | Matera et al., 2012 |

| 3 | 60/M | DM; rheumatoid arthritis methotrexate | − | + | ND | (a) Amoxicillin + trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (b) Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (c) Linezolid (d) Amoxicillin |

(a) 17 days (b) 20 days (c) 33 days (d) NR |

Survived | Coste et al., 2012 |

| 4 | 52/M | OLT in HCC secondary to hepatitis C and alcoholic cirrhosis; cyclosporine | + | + | Craniotomy with resection of the lesion | Ampicillin + gentamicin + penicillin G | 3 weeks (gentamicin only for 2 weeks) | Survived | Choudhury et al., 2013 |

| 5 | 56/F | Primary biliary cirrhosis; OLT; tacrolimus, azathioprine, prednisone | + | + | Biopsy | Ampicillin + gentamicin | 8 weeks (gentamicin only for 2 weeks) | Survived | Tseng et al., 2013 |

| 6 | 42/M | None | + | + | Biopsy and drainage | Ampicillin + gentamicin + meropenem | NR | Survived | Beynon et al., 2013 |

| 7 | 47/F | SLE; mycophenolate | − | + | ND | Ampicillin | 6 weeks | Survived | Horta-Baas et al., 2013 |

| 8 | 16/F | SLE; mycophenolate | + | − | External ventricles device | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole + ampicillin + meropenem | 13 weeks trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; ampicillin for 4 weeks; meropenem for 5 weeks (total of 22 weeks) | Survived | Perini et al., 2014 |

| 9 | 81/M | Myelodys plastic syndrome; basal cell skin carcinoma, prostate cancer treated | + | + | Craniotomy with resection of the lesion | Ampicillin | NR | Survived | West et al., 2015 |

| 10 | 52/F | DM, hypothyroidism, prednisolone, azathioprine | + | − | Biopsy | Ampicillin + gentamicin | 6 weeks | Survived | Al-HarabI et al., 2015 |

| 11 | 81/F | DM | NR | + | Biopsy | Ampicillin | 8 weeks | Survived | Dejesus-Alvelo et al., 2015 |

| 12 | 74/F | DM | + | NR | NR | Vancomycin + ampicillin + ceftriaxone | NR | Survived | Bojanowski et al. [17] |

| 13 | 32/F | LAC | + | NR | NR | Ampicillin + trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole + linezolid | 8 weeks; linezolid for 10 days | Survived | Fervienza et al., 2016 |

| 14 | 72/M | None | − | + | ND | Ampicillin | NR | Survived | Mano et al., 2017 |

| 15 | 52/M | Inflammatory myositis treated with prednisolone and azathioprine | + | − | ND | Ampicillin | 6 weeks | Survived | Onder et al., 2016 |

| 16 | 70/M | Alcoholism | + | + | ND | Ampicillin + gentamicin + vancomycin | 3–6 weeks | Died | Cone et al. [13] |

| 17 | 56/M | AIDS | + | − | ND | Ampicillin + gentamicin | Article not available | Survived | Patey et al., 1989 |

| 18 | 49/M | Rheumatic fever, alcoholism, DM | + | − | ND | Penicillin G + streptomycin + tetracycline | NR | Died | Buchner and Schneierson, 1968 |

| 19 | 64/M | DM, aortic valve replacement | + | − | ND | Ampicillin + gentamicin | 4 weeks + ampicillin for 2 weeks | Survived | Soto and Sliman, 1992 |

| 20 | 71/M | DM, rheumatic heart disease | + | − | ND | Ampicillin + gentamicin | NR | Died | Eckburg et al. [22] |

| 21 | 56/M | AIDS | + | − | ND | Ampicillin + gentamicin | Article not available | Survived | Patey et al., 1989 |

| 22 | 70/F | Cirrhosis, DM, heart failure | + | ND | ND | Ampicillin + trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Article not available | Died | Sivalinga et al., 1992 |

| 23 | 25/F | Ulcerative colitis | NR | NR | ND | NR | NR | Died | Larsson and Linell, 1979 |

| 24 | 87/M | None | + | + | ND | Penicillin G + chloramphenicol | NR | Died | Spilkin et al., 1968 |

| 25 | 63/M | None | + | − | ND | Ampicillin | NR | Died | Kennard et al., 1979 |

| 26 | 24/M | None | + | − | ND | Ampicillin + gentamicin | 6 weeks, gentamicin only for 10 days | Survived | Smiatacz et al., 2006 |

| 27 | 53/F | None | + | − | ND | Minocycline, gentamicin | 2 weeks | Survived | Mrowka et al., 2002 |

| 28 | 63/F | None | − | − | ND | NR | NR | Died | Brun-Buisson et al., 1985 |

| 29 | 43/F | None | − | − | ND | Ampicillin | NR | Died | Brun-Buisson et al., 1985 |

| 30 | 39/M | None | NR | − | ND | NR | NR | Died | Kwantes and Isaac, 1971 |

| 31 | 54/F | None | NR | NR | ND | NR | NR | Died | Larsson and Linell, 1979 |

| 32 | 1+1/4/M | None | NR | NR | ND | Amoxicillin | Article not available | Survived | Mancini et al., 1990 |

| 33 | 70/M | NONE | − | + | Craniectomy and open biopsy | Ampicillin | NR | Survived | Salgado et al., 1996 |

| 34 | 53/M | Cirrhosis, seizure | + | − | + | Penicillin G + erythtomycin | Article not available | Survived | Halkin et al., 1971 |

| 35 | 85/M | DM | + | − | + | Ampicillin | Article not available | Died | Brown et al., 1991 |

| 36 | 43/M | OSAS, alcoholism | + | − | + | NR | Article not available | Survived | Douen and Bourque, 1997 |

| 37 | 0/M | Pronatis | + | − | + | Ampicillin + gentamicin | Article not available | Survived | Banerji and Noya, 1999 |

| 38 | 63/M | MM | + | − | Biopsy | (a) Ampicillin | (a) 5 weeks | Survived | Leiti et al. [20] |

| (b) Linezolid + rifampin | (b) 15 weeks | ||||||||

| 39 | 61/M | DM | NR | NR | Biopsy | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole + chloramphenicol | 3 weeks, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole alone for 20 weeks | Survived | Sjostrom et al., 1995 |

| 40 | 60/M | HIV | NR | + | Craniotomy and intraoperative cultures | Penicillin G + chloramphenicol | NR | Died | Harris et al., 1989 |

| 41 | 68/M | Leukemia | NR | NR | ND | Chloramphenicol | NR | Died | Larsson et al., 1978 |

| 42 | NR/M | None | NR | NR | ND | NR | NR | Died | Pollock et al., 1984 |

| 43 | 2/M | NR | NR | + | Craniotomy with resection of the lesion | NR | NR | Survived | Umenai et al., 1978 |

| 44 | 49/M | Renal transplant | + | + | ND | Chloramphenicol | NR | Died | Crocker and Leicester, 1976 |

| 45 | 16/M | ALL | + | + | ND | Penicillin G + chloramphenicol | NR | Survived | Dykes et al., 1979 |

| 46 | 20/M | ALL | + | + | ND | Ampicillin + chloramphenicol + erythromycin, gentamicin | 8 weeks | Survived | Hutchinson and Heyn, 1983 |

| 47 | 6/F | ALL | + | + | ND | Ampicillin, vancomycin, netilmicin | NR | Survived | Viscoli et al., 1991 |

| 48 | 46/F | Ulcerative colitis | + | + | ND | Ampicillin, gentamicin | 8 weeks, 4 weeks | Survived | Soares-Fernandes et al., 2008 |

| 49 | 58/F | SLE | + | − | ND | Penicillin G + tobramycin | ARTICLE NOT AVAILABLE | Survived | Takano et al., 1999 |

| 50 | 58/F | Immunoblastic lymphadenopathy | + | − | ND | Ampicillin | 8 weeks | Survived | Maezawa et al. [21] |

| 51 | 65/M | DM | + | NR | ND | Ampicillin + gentamicin | 4 weeks | Died | Wu et al., 2010 |

| 52 | 19/M | Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, tetralogy of Fallot | NR | + | ND | Vancomycin + ampicillin | Article not available | Survived | Turner et al., 1995 |

| 53 | 55/M | Renal transplant | + | − | + | Ampicillin | Article not available | Survived | Lechtenberg et al., 1979 |

| 54 | 45/M | Renal transplant | + | − | Craniotomy and drainage | Ampicillin | 10 weeks | Survived | Stam et al., 1982 |

| 55 | 60/F | Rheumatoid arthritis | + | − | Biopsy | Ampicillin, amoxicillin | 8 weeks, 24 months | Survived | Updike et al., 1990 |

| 56 | 66/F | AML, Crohn's disease | + | + | Biopsy | Ampicillin | 4 weeks | Survived | Eckburg et al. [22] |

| 57 | 47/M | AIDS | + | − | Craniotomy | Ampicillin, gentamicin, vancomycin | NR | Died | Cone et al. [13] |

| 58 | 54/F | Sarcoidosis | + | − | Biopsy | Ampicillin + gentamicin | NR | Died | Ackermann et al., 2001 |

| 59 | 23/F | ITP | + | − | Drainage of the abscess | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 12 months | Survived | Treebupachatsaul et al., 2006 |

| 60 | 58/M | MM | + | − | Craniotomy and drainage | (a) Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole + gentamicin (b) Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | (a) 12 weeks (gentamicin only 2 weeks) (b) 5 months | Survived | Al-Khatti and Al- Tawfiq, 2010 |

| 61 | 55/M | Glioblastoma multiforme | − | + | Biopsy | Amoxicillin + gentamicin | 12 weeks | Survived | Ganiere et al., 2006 |

| 62 | 51/M | Cardiac transplant | + | + | Stereotactic brain aspiration | Ampicillin + gentamicin | 6 weeks, gentamicin only 2 weeks | Survived | Eckburg et al. [22] |

| 63 | 37/M | Cardiac transplant | + | + | Craniotomy with resection of the lesion | penicillin G | 8 weeks | NR | Eckburg et al. [22] |

| 64 | 56/F | Primary biliary cirrhosis | + | + | Biopsy | Ampicillin + gentamicin | 6 weeks gentamicin only 2 weeks | Survived | Cone et al. [13] |

| 65 | 50/M | Sarcoidosis | − | + | Craniotomy | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Article not available | Survived | Poropatich and Phillips, 1992 |

| 66 | 51/F | Crohn's disease | − | + | Biopsy | Ampicillin + gentamicin | 12 weeks (gentamicin not reported) | Survived | Stefanovich et al., 2010 |

| 67 | 50/M | Cardiac transplant, DM | − | + | Biopsy and aspiration | Ampicillin + gentamicin | 18 weeks of ampicillin; 14 weeks gentamicin | Survived | Eckburg et al. [22] |

| 68 | 75/M | None | − | ND | + | Ampicillin + gentamicin | Article not available | Survived | Mylonakis et al., 1998 |

| 69 | 77/M | CLL | − | NR | + | Chloramphenicol | Article not available | NR | Cleveland and Gelfand, 1993 |

| 70 | 58/M | CLL | − | + | Biopsy | Ampicillin + gentamicin | 6 weeks | Survived | Dee and Lorber, 1986 |

| 71 | Child | ALL | NR | NR | + | NR | Article not available | Survived | Antunes et al., 1998 |

| 72 | 68/F | Breast cancer | + | ND | Biopsy | Ampicillin, amoxicillin | 10 weeks, 24 weeks | Survived | Limmahakhun and Chayakulkeeree [1] |

| 73 | 47/F | Evans syndrome, SLE, DM | + | − | ND | Ampicillin, amoxicillin | 6 weeks, NR | Survived | Limmahakhun and Chayakulkeeree [1] |

| Case 1 | 62/M | None | + | + | Craniotomy with resection of the lesion | (a) Ampicillin + gentamicin (b) Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | (a) 8 weeks (gentamicin only 4 weeks) (b) 8 weeks | Survived | |

| Case 2 | 72/M | Bullous pemphigoid | + | + | Biopsy | (a) Ampicillin + gentamicin + trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (b) Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | (a) 5 weeks (b) 3 weeks | Survived | |

Forty-eight of these patients were male (64%). The mean age of the patients was 51.9, and median age was 55 years (range 0–87 years). Fifty-nine out of 73 had one or more risk factors described in the literature for the development of neurolisteriosis (81%), 15/75 had no risk factors (19%), and in 1 case, nothing was specified. The mortality rate was 27.3%.

Blood cultures were reported for 63 cases: 50/63 were positive (79.5%).

L. monocytogenes was isolated from the CSF or brain abscesses in 31/61 patients (50.8%).

The therapeutic regimen was reported for 67/75 cases, while it is unknown in 8/75.

Twenty-seven out of 67 patients received a monotherapy regimen (40%), while a combination therapy was prescribed for 40/67 (60%) cases: a two-drug therapy was prescribed in 31 cases (50.8%) and a three-drug therapy was administered in 9 cases (14.7%).

The mortality rate in the monotherapy regimen group was 18.5% (five patients out of 27) while the group that received combination therapy showed a 20% mortality rate (eight patients out of 40). Fifty-nine out of 67 patients received a beta-lactam regimen, while 8/59 received a free beta-lactam regimen.

Considering the substantial numerical difference of the two samples, these are not comparable.

Ampicillin was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic as it was administered to 49 patients: in 21 patients, it was prescribed as monotherapy; in 23 cases, it was administered in combination with gentamicin; in 3 cases, it was administered in combination with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole while in 2 cases, it was administered in combination with other drugs such as vancomycin or macrolides.

There are currently no guidelines for brain abscess management. Starting from the 2010 consensus on the management and treatment of brain abscesses, we reviewed our case series [24].

Thirty-nine out of 75 patients underwent neurosurgery (52%). Four out of 31 died (13%). Thirty-four patients out of 75 (45.3%) had only been treated with medical therapy. Of these, 15/34 died (38.2%). In 2 cases, no data have been reported.

Therefore, in our case series, taking into account all of the possible bias, mortality would appear to be significantly higher in the group of patients treated exclusively with medical therapy.

In our opinion, this is a very interesting finding which requires further investigation.

However, as yet, there is no evidence concerning the appropriate duration of therapy for those patients who underwent neurosurgery.

According to a recent consensus study, antimicrobial treatment for brain abscesses should generally last 6–8 weeks and treatment for those undergoing neurosurgery should last 4–6 weeks [24].

From our literature review, the duration of therapy was known in 36/75 patients. Sixteen out of 36 received less than or equal to 6 weeks while 20/36 patients were treated for 8 weeks or more. Of the group of patients who received ≤6 weeks of therapy, 4/16 (25%) underwent neurosurgery, while of those belonging to the group who received ≥8 weeks, 16/20 (80%) underwent neurosurgery.

A 12.5% mortality rate was observed for the first group while 0% died in the second group, thus suggesting that a combination of surgery and prolonged medical therapy has a positive impact on mortality.

We believe that it is essential to carry out this review as brain abscesses are rare, and there are no definitive guidelines on the optimal management, type, and duration of therapy. LM infection should also be suspected in immunocompetent patients, and new molecular biology techniques play key roles in the early diagnosis of this rare pathology.

4. Conclusions

In our literature review, we found that listeria brain abscess is not related to advanced age and that it is related to high mortality (27.3%).

Diagnosis should not be suspected only in immunocompromised patients as it was found in 20% of patients who had no risk factor.

Blood cultures were positive in more than 80% of cases. Most patients received a beta-lactam regimen, and mortality appears to be lower in patients treated with combination regimens.

This result looks certainly very interesting and should be explored with dedicated studies (i.e., sharp difference in mortality between the group undergoing neurosurgery and the group that only received medical therapy). Furthermore, the specific pattern of brain diffusion, reported and highlighted in our two clinical cases, should be considered when this diagnosis is hypothesized.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- 1.Limmahakhun S., Chayakulkeeree M. Listeria monocytogenes brain abscess: two cases and review of the literature. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2013;44(3):468–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pagliano P., Ascione T., Boccia G., De Caro F., Esposito S. Listeria monocytogenes meningitis in the elderly: epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic findings. Le Infezioni in Medicina. 2016;24(2):105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Noordhout C. M., Devleesschauwer B., Angulo F. J., et al. The global burden of listeriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2014;14(11):1073–1082. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70870-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pagliano P., Arslan F., Ascione T. Epidemiology and treatment of the commonest form of listeriosis: meningitis and bacteraemia. Le Infezioni in Medicina. 2017;25(3):210–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlier C., Perrodeau É., Leclercq A., et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors of listeriosis: the MONALISA national prospective cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2017;17(5):510–519. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vázquez-Boland J. A., Kuhn M., Berche P., et al. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2001;14(3):584–640. doi: 10.1128/cmr.14.3.584-640.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morosi S., Francisci D., Baldelli F. A case of rhombencephalitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes successfully treated with linezolid. Journal of Infection. 2006;52(3):e73–e75. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorber B. Listeriosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1997;24(1):1–11. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vázquez-Boland J. A., Krypotou E., Scortti M. Listeria placental infection. mBio. 2017;8(3) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00949-17.e00949-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Disson O., Lecuit M. Targeting of the central nervous system by Listeria monocytogenes. Virulence. 2012;3(2):213–221. doi: 10.4161/viru.19586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drevets D. A., Bronze M. S. Listeria monocytogenes: epidemiology, human disease, and mechanisms of brain invasion. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology. 2008;53(2):151–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlüter D., Chahoud S., Lassmann H., Schumann A., Hof H., Deckert-Schlüter M. Intracerebral targets and immunomodulation of murine Listeria monocytogenes meningoencephalitis. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1996;55(1):14–24. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cone L. A., Leung M. M., Byrd R. G., Annunziata G. M., Lam R. Y., Herman B. K. Multiple cerebral abscesses because of Listeria monocytogenes: three case reports and a literature review of supratentorial listerial brain abscess(es) Surgical Neurology. 2003;59(4):320–328. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(03)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dons L., Weclewicz K., Jin Y., Bindseil E., Olsen J. E., Kristensson K. Rat dorsal root ganglia neurons as a model for Listeria monocytogenes infections in culture. Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 1999;188(1):15–21. doi: 10.1007/s004300050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guldimann C., Lejeune B., Hofer S., et al. Ruminant organotypic brain-slice cultures as a model for the investigation of CNS listeriosis. International Journal of Experimental Pathology. 2012;93(4):259–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2012.00821.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oevermann A., Di Palma S., Doherr M. G., Abril C., Zurbriggen A., Vandevelde M. Neuropathogenesis of naturally occurring encephalitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes in ruminants. Brain Pathology. 2010;20(2):378–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bojanowski M. W., Seizeur R., Effendi K., Bourgouin P., Magro E., Letourneau-Guillon L. Spreading of multiple Listeria monocytogenes abscesses via central nervous system fiber tracts: case report. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2015;123(6):1593–1599. doi: 10.3171/2014.12.JNS142100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartt R. Listeria and atypical presentations of Listeria in the central nervous system. Seminars in Neurology. 2000;20(3):361–373. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matano S., Satoh S., Harada Y., Nagata H., Sugimoto T. Antibiotic treatment for bacterial meningitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes in a patient with multiple myeloma. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy. 2010;16(2):123–125. doi: 10.1007/s10156-009-0014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leiti O., Gross J. W., Tuazon C. U. Treatment of brain abscess caused by Listeria monocytogenes in a patient with allergy to penicillin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;40(6):907–908. doi: 10.1086/428355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maezawa Y., Hirasawa A., Abe T., et al. Successful treatment of listerial brain abscess: a case report and literature review. Internal Medicine. 2002;41(11):1073–1078. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.41.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckburg P. B., Montoya J. G., Vosti K. L. Brain abscess due to Listeria monocytogenes: five cases and a review of the literature. Medicine. 2001;80(4):223–235. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samra Y., Hertz M., Altmann G. Adult listeriosis–a review of 18 cases. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1984;60(702):267–269. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.60.702.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arlotti M., Grossi P., Pea F., et al. Consensus document on controversial issues for the treatment of infections of the central nervous system: bacterial brain abscesses. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;14(4):S79–S92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]