Abstract

The promoters of two mouse ribosomal protein genes, rpL30 and rpL32, contain a similarly located element, called β, which was previously shown to interact with the same nuclear protein. This protein has now been identified as the GA-binding protein (GABP) on the basis of studies with recombinant GABP subunits and GABP-specific antibodies. The rpL30 element consists of two contiguous GABP binding sites that can form a tetrameric complex with two α and two β1 subunits of GABP, as well as dimeric complexes with α and either the β1 or β2 subunit. The rpL32 element consists of a solitary GABP binding site that can form only dimeric complexes with a and β1 or β2. Footprint analysis and a comparison of the effects of mutations in each of the tandem rpL30 binding sites demonstrated that the site nearest to the transcriptional start point is strongly favored for dimeric complex formation and is correspondingly more important for rpL30 promoter function. The contributions to overall promoter activity of the proximal rpL30 site and the solitary rpL32 site are virtually the same. Paradoxically, the potential for tetramer formation afforded by the tandem sites in rpL30 has a relatively minor effect on overall promoter strength. These findings illustrate the subtlety of mechanisms by which fine-tuning of rp promoters is achieved.

The mammalian ribosome is a complex organelle comprising four RNA components and about eighty distinct proteins. Coordinate expression of the genes encoding these proteins is vital for the growth and maintenance of all cell types. Although the various ribosomal protein (rp) genes are widely dispersed in the genome, they are transcribed at very similar rates owing to the equivalent strengths of their promoters (Hariharan et al., 1989). The strength of each promoter depends upon the particular combination of transcription factors that bind to its sequence elements. The way in which such factors act to stimulate transcriptional activity is still poorly understood. To gain further insight into this process, it is important to identify the factors and to determine their particular roles in different rp promoters.

Previous studies defined three similarly located cis-acting elements that contribute positively to the overall promoter activity of both the rpL30 and rpL32 genes (Hariharan et al., 1989). These elements were shown to contain binding sites for nuclear protein factors β, γ, and δ (Fig. 1). The rpL30/L32-γ and rpL30/L32-δ proteins have been purified in our laboratory, and a cDNA for rpL30/L32-δ was isolated and characterized (D. E. Kelley, unpublished data; Hariharan et al., 1991). The binding site for rpL30-β, located 53 to 64 bp upstream of the transcriptional start point, contains a tandemly repeated sequence — (CGGAAR)2 — that is identical to a motif in the enhancer of a herpesvirus immediate early gene (HSV-IE), which interacts with a transcription factor called GA-binding protein (GABP; Thompson et al., 1991). In contrast, the rpL32-β site contains a single CGGAAR sequence at position −76 to −71. It has recently been reported that the rpL32-β site binds a protein that is immunologically related to GABP (Yoganathan et al., 1992).

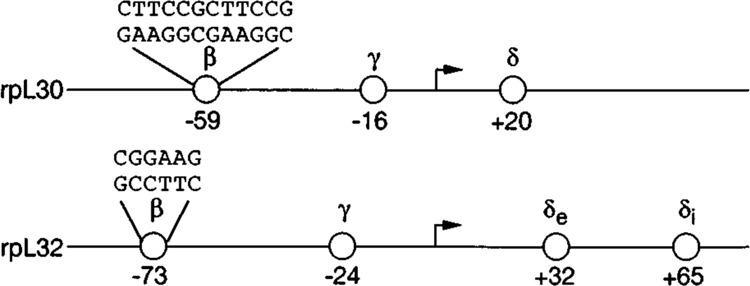

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the promoters of the rpL30 and rpL32 genes showing the locations of the β, γ, and δ elements and sequences of the β factor binding sites. The coordinates represent the approximate centers of the elements, as determined by DNase I or methylation interference footprint analyses.

GABP is a heterodimeric protein. cDNAs encoding both subunits were cloned and sequenced by LaMarco et al. (1991). Analysis of the amino acid sequence showed that the GABPα subunit is a member of the Ets family of DNA-binding proteins and that the GABPβ subunit contains Notch-related structural motifs. By itself, the α subunit can weakly bind to DNA, whereas the β subunit binds to DNA only when the α subunit is present (Thompson et al., 1991). There are two isoforms of GABPβ, termed β1 and β2, which have completely different C-terminal ends (LaMarco et al., 1991). HSV-IE DNA forms considerably more stable complexes with α and β1 subunits than with α and β2 subunits, presumably because β1 subunits on each of the tandem sites can associate to produce an (αβ1)2 tetramer, whereas such an association between β2 subunits does not occur (Thompson et al., 1991).

To determine whether and how GABP interacts with the rpL30 and rpL32 promoters, we carried out electrophoretic mobility-shift assays (EMSA) and footprinting assays with recombinant GABP proteins and antibodies raised against these proteins. Additionally, to investigate the relative contribution to promoter activity of the solitary GABP site in rpL32 versus the tandem GABP sites in rpL30, we made mutations in each of the sites and tested the activity of the mutants in transient transfection experiments. Our results indicate that GABP interacts effectively with both the rpL30 and the rpL32 promoters. Furthermore, we observed that each of the tandem rpL30 sites has a different affinity for GABP and that the affinity correlates with the value of the site for rpL30 promoter activity. Interestingly, the contributions of the solitary site in rpL32 and the high affinity site in rpL30 are virtually the same. The additional GABP binding site and the potential for tetramer formation has a relatively small effect on the overall strength of the rpL30 promoter.

Materials and methods

Nuclear extracts and EMSA

Nuclear extracts were prepared from S194 mouse plasmacytoma cells by the method of Dignam et al. (1983). Recombinant GABPα, GABPβ1, and GABPβ2 subunits and rabbit antibodies against GABPα and GABPβ were generous gifts from Catherine Thompson and Steve McKnight. GABP binding activity was determined by EMSA. The binding reactions contained 20 mM Hepes-K+ (pH 7.9), 50 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 10% glycerol. Two μg poly(dI-dC)poly(dI-dC) were added as nonspecific competitor when nuclear extracts were used. Unless stated otherwise, nuclear extracts (2–5 μg protein) or recombinant GABP subunits (approximately 3 nM) were incubated at 25°C for 15 minutes in a 25 μl reaction with 0.1–0.5 ng of end-labeled, double-stranded oligonucleotides. The reactions were analyzed by electrophoresis in nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) or 0.25× TBE, as indicated.

DNase I footprint analysis

DNA probes for DNase I footprinting were generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with oligonucleotide primers 5′ and 3′ to the rpL30 or rpL32 GABP binding sites. Either the sense or antisense primer was 5′ end-labeled prior to PCR. Recombinant GABP subunits were incubated with a 32P-labeled DNA fragment under conditions described for EMSA. Free DNA and protein-bound DNA were partially digested with DNase I and subjected to electrophoresis on 4% polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× TBE. Free DNA and protein-bound DNA were identified, excised from the gel, recovered by electrocution, and subjected to electrophoresis on an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 7M urea. DNA sequencing markers were electrophoresed in parallel.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the rpL30 and rpL32 CABP sites

All site-directed mutations were generated by PCR using the rpL30-CAT construct “g” (−205 to +167; Hariharan et al., 1989) or the rpL32-CAT construct (−159 to +115; Atchison et al., 1989), both of which utilized the CAT expression vector pl06. These constructs contain all the elements, including those in the first intron, that are required for maximal promoter activity. To generate an individual mutant, primer 1 (sense strand) containing a mutation in the rpL30 or rpL32 GABP site and primer 3, complementary to CAT vector sequences, were used in PCR. Primer 2 (a reverse complement of primer 1) and primer 4, containing sequences 5′ to the multiple cloning site of the vector pl06, were also used in PCR. Both PCR products were purified using Stratagene Prime Erase Push Columns, and equal amounts were mixed and used as template for an additional PCR with primers 3 and 4. The final PCR product was digested with Hind III and Sma I, gel purified, and cloned in Hind III and Sma I sites of pl06. Each site-directed mutant was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Cell culture and DNA transfection

S194 mouse plasmacytoma cells (ATCC TIB19) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% horse serum and antibiotics. Approximately 2 × 107 cells were transfected with 5 μg of plasmid by the DEAE-dextran procedure, followed by a 30 minute treatment with chloroquine diphosphate (Grosschedl and Baltimore, 1985). Cells were harvested approximately 40 hours after transfection. Extract preparation, CAT assays, and thin-layer chromotography were performed essentially as described by Gorman et al. (1982). CAT activity was quantified with an Ambis radioimage analyzer.

Oligonucleotides

The following oligonucleotides were used. Mutations are in lower case.

-

rpL30(−70 to −37) wt

(5′-AATTCCTTCTCTTCCCCTTCCCCTCCCACAATCCTCTC-3′)

and

(3′-CCAACACAACCCCAACCCCACCCTCTTACCACACTTAA-5′)

-

rpL30 Al site mutant

(5′-CCTTCTCcTCCCCTTCCCCTCCCACAATCCTCT-3′)

and

(3′-CCAACACgACCCCAACCCCACCCTCTTACCACA-5′)

-

rpL30 A2 site mutant

(5′-CCTTCTCTgCCCCrTCCCCTCCCACATCCTCT-3′)

and

(3′-CCAACACAcCCCCAACCCCACCCTCTTACCACA-5′)

-

rpL30B site mutant

(5′-CCTTCTCTTCCCCTgCCCCTCCCACAATCCTCT-3′)

and

(3′-CGAACAGAAGCCCAcCCCCACCCTGTTAGGACA-5′)

-

rpL30 AB double site mutant

(5′-GCTTCTCcTCCGCTgCCGGTCCCACAATCCTCT-3′)

and

(3′-CGAAGAGgAGGCGAcGGCCAGGGTGTTAGGAGA-5′).

-

rpL32(−83 to −54) wt

(5′-AATTCCAGAGCCGGMGTGCTTCCCTTTTCTCTG-3′)

and

(3′-GGTCTCGGCCTTCACGAAGGGAAAAGAGACTrAA-5′)

-

rpL32 mutant

(5′-CCCAGAGCCtGAAGTGCTTCCCTTTTCTCT-3′)

and

(3′-GGGTCTCGGaCTTCACGAAGGGAAAAGAGA-5′)

-

HSV IE

(5′-AACCAAGCTTGCGGAACGGAAGCGGAAACC-3′)

and

(3′-TTGGTTCGAACGCCTTGCCTTCGCCTTTGG-5′)

-

PCR primer 3

(5′-CTCCATTTTAGCTTCCTrAGCTCCTGAAAATCTCGCC-3′)

-

PCR primer 4

(5′-ATGATTACGCCAAGCTTG-3′).

Results

Antibodies specific to CABP subunits recognize the rpL30/L32-β factor

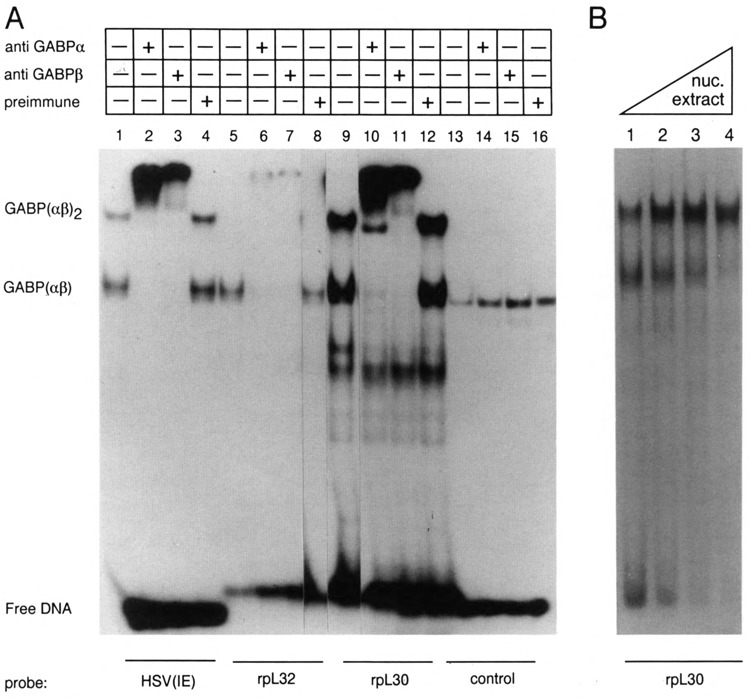

To determine whether GABP binds to the rpL30/L32-β sites, oligonucleotides representing sequences in the rpL30 (−70 to −37) or rpL32 (−83 to −54) promoters or the enhancer of the HSV-IE gene ICP4 were incubated with nuclear extract in the presence or absence of rabbit antibodies specific for each GABP subunit. We observed two retarded complexes that have the same mobilities with the HSV-IE and rpL30 probes, both of which contain tandem GABP sites (Fig. 2A; compare lanes 1 and 9). We interpret the lower and upper bands to represent complexes with GABP dimers on one or both binding sites — GABP(αβ) and GABP(αβ)2, respectively. This interpretation was confirmed by several lines of evidence, including a titration of the rpL30 binding sites, in which the proportion of the upper band increased with increasing amounts of nuclear extract (Fig. 2B), footprint analysis (Fig. 4B), and experiments with rpL30 binding site mutants (Fig. 5A). No upper band was observed with the rpL32 probe (Fig. 2A, lane 5), consistent with the fact that it contains only a single GABP site. As observed for the HSV-IE control (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 3), the rpL30 and rpL32 complexes were both super-shifted by antibodies specific for either the α or β subunit of GABP (Fig. 2A, lanes 6, 7, 10, 11). This indicates that the sites in both the rpL30 and rpL32 genes bind GABP as a heterodimer. No supershift was observed in the following control experiments: (1) with serum from a nonimmunized rabbit (Fig. 2A, lanes 4, 8, and 12); (2) with an oligonucleotide that lacks a GABP binding site (Fig. 2A, lanes 13–16); and (3) when 1/20 diluted antibodies and probe were mixed without nuclear extract (data not shown). The results of these control experiments confirm the specificity of the GABP antibodies for the β-site binding proteins. These experiments cannot distinguish between αβl and αβ2 heterodimers because the β subunit antibodies would recognize both isoforms. This issue was specifically addressed in experiments with recombinant GABP proteins (see below).

Figure 2.

Antibodies specific to GABP subunits recognize the rpL30/L32-β factor. A. S194 nuclear extract was incubated with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide containing a GABP binding site derived from the enhancer of the Herpes simplex virus ICP4 gene [HSV(IE)], rpL32 (−83 to −37), or rpL30 (−70 to −37) in the presence or absence of rabbit antibodies, as indicated at the top of the figure. Rabbit antibodies at a dilution of 1/20 were incubated with nuclear extract for 5 minutes at room temperature prior to the addition of labeled oligonucleotides. Control incubations contained a rpL30 oligonucleotide (−35 to −1), which does not contain a GABP binding site, but rather contains a binding site for the factor, a homodimeric protein of similar size as GABP. The reactants were subjected to electrophoresis on a 4% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× TBE. The bands corresponding to the tetrameric (αβ)2 and the dimeric (αβ) complexes are indicated. B. The ratio of (αβ)2 to (αβ) increases with increasing ratio of nuclear extract to probe. Lanes 2, 3, and 4 contained 2-, 3-, and 5-fold more protein than lane 1.

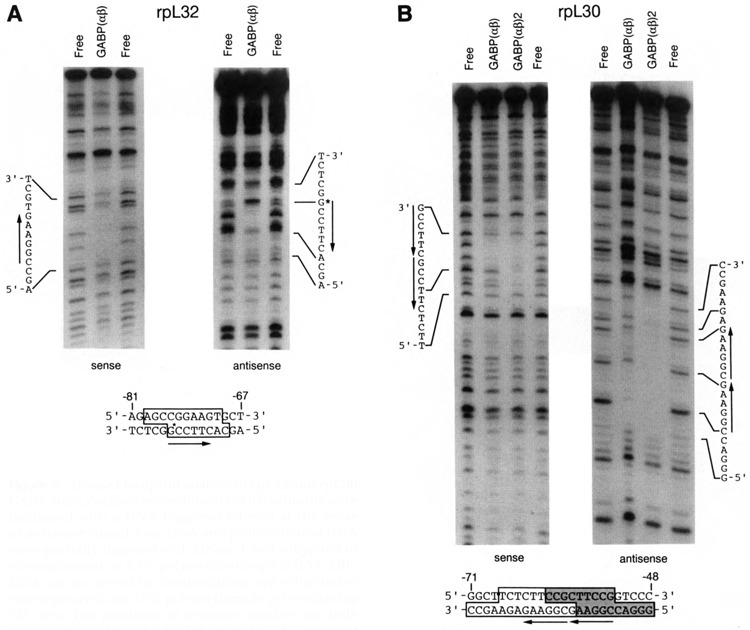

Figure 4.

DNase I footprint analysis of rpL32 and rpL30 GABP sites. Purified recombinant GABP subunits were incubated with a DNA fragment labeled at the sense or antisense strand. Free DNA and protein-bound DNA were partially digested with DNase I and subjected to electrophoresis on a 4% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE. DNA was recovered by electroelution and subjected to electrophoresis on a 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 7M urea. The positions of sequence markers are indicated at the right and left of the panels. A. Fragment corresponding to the −126 to −13 region of rpL32. B. Fragment corresponding to the −125 to −6 region of rpL30. At the bottom of the figures, the sequences of the protected regions are delineated by boxes. The stippled portion of the rpL30 box was protected in both the αβ1 and (αβ1)2 complexes; the nonstippled portion was protected only in the (αβ1)2 complex.

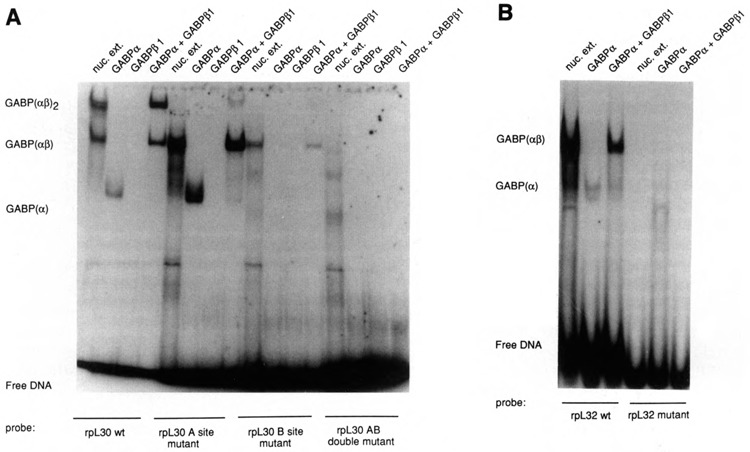

Figure 5.

Analysis of rpL30 and rpL32 GABP binding-site mutants. Purified recombinant GABP subunits or SI94 nuclear extract were incubated with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing wild-type GABP sites or sites with point mutations (see Table 1). The reactants were subjected to electrophoresis on a 4% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× TBE. A. rpL30. Results with the A1 mutant are shown here; similar results were obtained with the A2 mutant. B. rpL32.

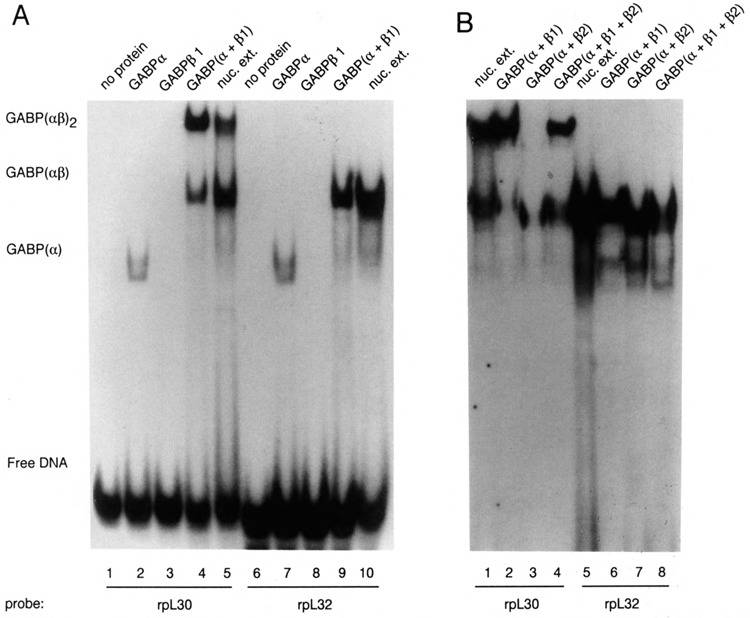

Binding of recombinant GABP subunits to the rpL30/L32-β sites

Recombinant GABP subunits were used to examine further the binding of GABP to the rpL30 and rpL32 promoters. As shown in Figure 3A, a mixture of GABPα and GABPβ1 subunits formed complexes with the rpL30 and rpL32 probes that were very similar to those formed with nuclear extract proteins (lanes 4, 5, 9, 10). Consistent with previous findings by Thompson et al. (1991), the α subunit — but not the β1 subunit – can weakly bind to DNA in the absence of its dimeric partner (lanes 2, 3, 7, 8). A similar experiment with a mixture of GABPα and GABPβ2 subunits showed good binding to the rpL32 solitary site (Fig. 3B, lane 7) and to one of the two tandem sites in rpL30 (Fig. 3B, lane 3). In agreement with the inability of β2 subunits to associate with each other (Thompson et al., 1991), there was little or no (αβ2)2 tetramer formation on the rpL30 tandem sites (compare lanes 2, 3, and 4 of Fig. 3B). Since the β2 subunit is slightly smaller than the β1 subunit (37 kD versus 41.5 kD), the mobility of the dimeric complex αβ2 is slightly faster than that of αβ1 — most clearly seen with the solitary L32 site (Fig. 3B, lanes 6 and 7). The broad band observed with nuclear extract protein (Fig. 3A, lane 10; Fig. 3B, lane 5) resembles that seen with a mixture of αβ1 and αβ2 complexes (Fig. 3B, lane 8). It would appear, therefore, that a single GABP site can effectively bind dimers composed of a and either β1 or β2, whereas tetramer formation on a tandem GABP site can occur only with α and β1. Since we were interested in comparing the importance of GABP for promoters with solitary and tandem binding sites, we focused our attention on the α and β1 subunits, which interact equally well with both types of promoter.

Figure 3.

Recombinant GABP subunits bind to the rpL30/L32-β site. 32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing the GABP binding sites of rpL30 and rpL32 were incubated with either purified recombinant GABP subunits or S194 nuclear extract. Binding reactions containing approximately 20 ng of the indicated recombinant proteins were subjected to electrophoresis on a 4% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× TBE. A. Assays of α and β1 complexes. B. Comparison of αβ1 and αβ2 complexes. In this particular experiment, the GABP(αβ2) complex with the rpL30 probe was largely confined to the edges of lane 3 because of a problem with sample loading.

DNase I footprint analysis confirmed the GABP binding sites in the rpL32 and rpL30 promoters. GABP protects a region on the rpL32 DNA fragment equivalent to one GABP binding site (Fig. 4A). In addition, a hypersensitive DNase I site was observed on the rpL32 antisense DNA strand. Protein-DNA complexes corresponding to both GABP(αβ1) and GABP(αβ1)2 were characterized on rpL30 DNA (Fig. 4B). As expected, when the GABP(αβ1)2 complex was characterized, a site of DNase I protection encompassing both GABP sites was observed. Interestingly, when the GABP(αβ1) complex was analyzed, the site proximal to the transcriptional initiation site on both sense and antisense strands was consistently protected from DNase I digestion to a greater extent than the distal site, suggesting that the affinity of the proximal site for GABP is greater than that of the distal site. This observation was confirmed when mutants with substitutions in each of the sites were analyzed by EMSA and transfection studies (see below).

Analysis of rpL30 and rpL32 GABP-site mutants

The DNase I footprint analysis of the rpL30 dimeric complexes suggested that the two tandem sites do not bind GABP with the same affinity. To test this hypothesis, single point mutations (Table 1) were introduced into each site, and the effect on GABP binding was characterized. When oligonucleotides with a point mutation in the distal site (Al or A2 mutants) were incubated with either nuclear extract or recombinant GABP subunits, the GABP(αβl) complex was readily formed (Fig. 5A; Table 1). However, these mutants formed negligible amounts of GABP(αβ1)2 complex, indicating that two intact sites are required to form stable GABP(αβ1)2 tetramers. When an oligonucleotide with a point mutant in the proximal site (B mutant) was analyzed, a reproducibly lower amount of the GABP(αβ1) complex was observed compared to that formed with the A mutants, and no GABP(αβ1)2 complex was observed. An oligonucleotide with point mutations in both sites (AB double mutant) failed to bind any GABP. The same result was obtained irrespective of whether the nucleotide substitutions were at a different (Al) or a corresponding (A2) position in the A and B sites (Table 1), indicating that this effect is due to an intrinsic difference in the affinity of the two sites, rather than a difference in the efficacy of the particular point mutations. The effects of these mutations are in good agreement with the footprinting data, suggesting that the proximal rpL30 GABP site has a greater affinity for GABP than the distal site.

Table 1.

Effect of mutations on GABP binding and rpL30/rpL32 promoter activity.

| Binding was assayed by EMSA, as shown in Figure 5. For activity measurements, the rpL30 and rpL32 promoters (−205 to +167 and −159 to +115, respectively) containing wild-type or mutant GABP binding sites were linked to a cat reporter plasmid and transfected into SI 94 plasmacytoma cells. Extracts of cells harvested 40 hours after transfection were assayed for CAT activity and normalized to the values for the wild-type promoter. The mean values for duplicate assays of two to five independent transfection experiments are listed together with the average deviations. For ease of comparison of common motifs, the sequences on the minus strand of rpL30 and the plus strand of rpL32 are listed. | ||||

| Gene | Proximal(B) site | distal(A) site | Binding complex | Activity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| αβ1 | (αβ1)2 | |||

| rpL30 | ||||

| wild-type | 5′-CGGAAGCGGAAG-3′ | ++ | ++ | 100 |

| A1 mutant | CGGAAGCGGAgG | ++ | − | 78 ± 18 |

| A2 mutant | CGGAAGCGGcAG | ++ | − | 69 ± 8 |

| B mutant | CGGcAGCGGAAG | + | − | 42 ± 13 |

| AB mutant | CGGcAGCCCAgG | − | − | 27 ± 7 |

| rpL32 | ||||

| wild-type | 5′-CGGAAG-3′ | ++ | − | 100 |

| mutant | CtGAAG | − | − | 44 ± 8 |

To examine the effects of these mutations on the activity of the rpL30 promoter, we cloned the GABP-site mutants into rpL30 constructs linked to a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase reporter gene (cat) and assayed the relative activities after transient transfection into S194 cells. In good agreement with the in vitro binding analyses, we observed that the rpL30 proximal site mutant has an activity that is about 40% of the wild-type promoter, whereas the activity of the distal site mutants was about 75% of the wild-type level (Table 1). Mutation of both rpL30 GABP sites resulted in a residual promoter activity of approximately 25 to 30%, which is roughly additive of the effects of the individual site mutations.

The effects of a point mutation in the rpL32 GABP site were also investigated. This mutation abolished binding of both nuclear extract and recombinant GABP proteins (Fig. 5B) and reduced rpL32 promoter activity to about 45% of the wild-type level (Table 1). Thus the contribution to promoter activity of the solitary GABP site in rpL32 is basically the same as that of the high affinity site in rpL30.

Discussion

Several pieces of evidence indicate that GABP is an important positive regulator of the ribosomal protein genes rpL30 and rpL32. First, antibodies specific for the α and β subunits of GABP recognize a nuclear protein (previously termed the β factor) that binds to functionally important elements of the rpL30 and rpL32 promoters. Second, recombinant GABP proteins bind to these elements and give DNase I footprints on the known GABP core motif, CGGAAR. Third, point mutations in this motif had corresponding effects on GABP binding in vitro and on transcriptional activity in vivo.

In general, the interaction of GABP with the rpL30 promoter resembles that observed with the enhancer of the herpesvirus ICP4 gene. In both cases, two GABPα and two GABPβ1 subunits form a tetrameric complex (αβ1)2 on two contiguous CGGAAR motifs. Although the α subunit itself can bind weakly to DNA, the stability of the tetrameric complex appears to depend on an interaction between the C-terminal portions of the β1 subunits (Thompson et al., 1991). The β2 subunit lacks this C-terminal segment and is therefore ineffective in forming tetrameric complexes on both the ICP4 promoter (Thompson et al., 1991) and the rpL30 promoter (Fig. 3B).

Interestingly, the tandem sites in rpL30 do not have equivalent affinities for GABP. In mobility-shift experiments carried out with limiting amounts of protein — for example, Fig. 2A and B (lane 1) and Fig. 3A — a substantial proportion of the probe has GABP bound only to one of the two contiguous sites, and in rpL30 this site is predominately the one that is proximal to the transcriptional start point, as indicated by DNase I footprinting analysis. Moreover, point mutations in this proximal (B) site almost completely obliterate GABP binding, whereas identical mutations in the distal (A) site only prevent assembly of the tetrameric complex. Thus, the proximal site would be favored for the formation of dimeric complexes, which could become critical when the amount of GABP is limiting or the ratio of β2 to β1 subunit is high. This affinity difference probably accounts for the fact that mutations in the proximal GABP site have a more deleterious effect on in vivo promoter activity than mutations in the distal site.

The solitary GABP site in the rpL32 promoter forms dimeric complexes equally well with α and either the β1 or the β2 subunits. Since αβ1 dimeric complexes are more stable than complexes with a alone, stabilization at solitary sites must involve an interaction other than β1–βl association. A.similar interaction probably also occurs with the β2 subunit. Mutagenesis studies indicate that the contribution of GABP to promoter activity in rpL32 is comparable to that in rpLSO when only the high affinity site is occupied. The potential for tetrameric complex formation on the tandem rpL30 sites is associated with a moderate increment (1.3- to 1.6-fold) in promoter strength over that achieved with dimeric complexes, presumably because this potential is only partially realized in vivo.

A survey of the −100 to +20 regions of 18 other vertebrate rp genes revealed 23 possible GABP binding sites (Table 2). Several of these examples resemble the rpL32 promoter in that there is a single GABP target site upstream of the transcriptional start point. The GABP sites occur in both orientations with respect to the direction of transcription, as is the case in rpL30 versus rpL32. The site in the Xenopus rpL14 gene has been shown to be a positive activator of transcription and to bind a factor that is immunologically related to GABPα and GABPβ (M. Marchioni et al., 1993). Although four genes — rpL7(m), rpS6(h), rpS14(h), and rpS15(c) — have multiple GABP sites, these sites are not contiguous, as they are in rpL30 and the herpes-virus ICP4 gene. In rpL7(m), rpS16(m), rpS14(h), rpS6(h), and rpS15(c), putative GABP sites are located immediately downstream of the transcriptional start point. We demonstrated previously that the region of rpS16 containing the GABP site is important for promoter function (Hariharan and Perry, 1989), and recently we verified that this site does indeed bind GABP. It is noteworthy that in 23 of the 26 listed examples, the proposed binding site sequence is (C/G)CGGAAR. Thus, there may be a preference for C or G in the position immediately 5′ of the CGGAAR consensus.

Table 2.

Occurrence of the GABP consensus binding site sequence (XCGCAAR) in the −100 to +20 regions of vertebrate rp genes.

| Sequences of rp genes are from twenty Genbank/EMBL compilations. rpL13a(m) is listed as tum− transplantation antig ub/rp-52 is a ubiquitin/ribosomal protein fusion gene, mouse; r, rat; h, human; c, chicken; X, Xenopus laevis. The genes that lack GABP sites in the region scanned are rpL7a(m), rpL7a(h), rpS15(h), rpS8(h), and rpL1(X). | |||

| Gene | Positions of X/R | Identity of X/R | Strand |

|---|---|---|---|

| rpL30(m) | −52/58 | C/G | − |

| −58/64 | G/G | − | |

| rpL32(m) | −77/71 | C/G | + |

| rpL7(m) | −72/78 | C/A | − |

| +16/10 | C/A | − | |

| rpL13a(m) | −82/76 | A/A | + |

| rpS16(m) | +10/4 | C/A | − |

| rpP2(r) | −96/102 | C/G | − |

| rpS15(r) | −76/70 | G/G | + |

| rpS17(h) | −52/58 | G/G | + |

| rpS14(h) | −82/88 | C/G | − |

| −42/48 | C/G | − | |

| −38/32 | A/G | + | |

| +10/4 | C/A | − | |

| ub/rp-52(h) | −12/18 | C/A | − |

| rpL26(h) | −21/15 | C/G | + |

| rpS6(h) | −104/98 | C/G | + |

| −72/78 | G/G | − | |

| −13/7 | G/G | + | |

| +11/5 | A/A | − | |

| rpL7a(c) | −70/76 | C/A | − |

| rpS15(c) | −75/69 | G/G | + |

| −37/43 | G/G | − | |

| −3/9 | C/G | − | |

| +11/5 | G/A | − | |

| rpL14(X) | −45/51 | C/G | − |

Recently, GABP has been implicated in the promoter function of the murine genes that encode cytochrome c oxidase (COX) subunits IV and Vb (Carter et al., 1992; Virbasius et al., 1993). In the COXVb gene, three noncontiguous GABP binding sites are located on both sides of a set of multiple transcriptional start points, whereas in COXIV, the sites occur in the immediate vicinity of the start points. Thus, in both the rp and the COX genes, GABP may play a variety of roles in transcriptional activation, depending on its location within the promoter. It is clear from both the COX gene studies and from our studies of rp genes that the arrangement of tandem GABP sites found in the herpesvirus ICP4 promoter, which confers a potential for GABP tetramer formation, is not essential for GABP utilization. The widespread occurrence of this transcription factor in a variety of tissues (LaMarco et al., 1991), its flexibility with regard to binding site arrangement and location, and its presence in genes encoding critical components of the translational and respiratory machinery point to its vital role in higher eukaryotes.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to Drs. C. Thompson and S. McKnight for their gift of the GABP reagents.

Research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (DMB-8918147) and the National Institutes of Health (AI-17330, CA-06927, CA-09035-18, RR-05539), and by an appropriation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

The costs of publishing this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- Atchison M. L., Meyuhas O., and Perry R. P. (1989), Mol Cell Biol 9, 2067–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. S., Bhat N. K., Basu A., and Avadhani N. G. (1992), J Biol Chem 267, 23418–23426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam J. D., Lebovitz R. M., and Roeder R. G. (1983), Nucleic Acids Res 11, 1475–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman C. M., Moffat L. F., and Howard B. H. (1982), Mol Cell Biol 2, 1044–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosschedl R. and Baltimore D. (1985), Cell 41, 885–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan N. and Perry R. P. (1989), Nucleic Acids Res 17, 5323–5337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan N., Kelley D. E., and Perry R. P. (1989), Genes Dev 3, 1789–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan N., Kelley D. E., and Perry R. P. (1991), Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88, 9799–9803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMarco K., Thompson C. C., Byers B. P., Walton E. M., and McKnight S. L. (1991), Science 253, 789–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchioni M., Morabito S., Salvati A. L., Beccari E., and Carnevali F. (1993), Mol Cell Biol 13, 6479–6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. C., Brown T. A., and McKnight S. L. (1991), Science 253, 762–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virbasius J. V., Virbasius C.-M. A., and Scarpulla R. C. (1993), Genes Dev 7, 380–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoganathan T., Bhat N. K., and Sells B. H. (1992), Biochem J 287, 349–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]