Abstract

Introduction:

The mammalian SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich serine-threonine kinase SPAK (STK39) modulates the transport across and between epithelial cells in response to environmental stimuli such osmotic stress and inflammation. Research over the last decade has established a central role for SPAK in the regulation of ion and water transport in the distal nephron, colonic crypts, and pancreatic ducts, and has implicated deregulated SPAK signaling in NaCl-sensitive hypertension, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, and cystic fibrosis.

Areas covered:

We review recent advances in our understanding of the role of SPAK kinase in the regulation of epithelial transport. We highlight how SPAK signaling - including its upstream Cl--sensitive activators, the WNK kinases, and its downstream ion transport targets, the cation- Cl--cotransporters contribute to human disease. We discuss prospects for the pharmacotherapeutic targeting of SPAK kinase in specific human disorders that feature impaired epithelial homeostasis.

Expert opinion:

The development of novel drugs that antagonize the SPAK-WNK interaction, inhibit SPAK kinase activity, or disrupt SPAK kinase activation by interfering with its binding to Μ025α/β could be useful adjuncts in essential hypertension, inflammatory colitis, and cystic fibrosis.

Keywords: Blood pressure regulation, cation-chloride cotransporters (CCCs), ion homeostasis, kinase inhibitors, signal transduction, SPAK phosphorylation

1. Introduction

Protein kinases have become one of the most important classes of drug targets in medicine, particularly in the field of oncology [1]. In the past decade, more than 20 different drugs targeting kinases have been approved for clinical use in humans for the treatment of various types of cancer [2]. However, the use of kinase inhibitors in other human diseases, including those with cardiovascular, renal, neurological, and psychiatric phenotypes, have lagged behind despite the existence of promising kinase targets identified by genetic studies in humans and model organisms [2].

SPAK (SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich kinase) and OSR1 (oxidative stress-responsive kinase 1) are closely related protein kinases, which play key roles in regulating cellular ion homeostasis and blood pressure (BP) [3, 4]. SPAK and OSR1 are activated following the phosphorylation of their T-loop residue (SPAK Thr233 and OSR1 Thr185) by one of the four isoforms of the WNK [with no lysine (K) kinase] protein kinase [5, 6]. The activity of SPAK and OSR1 is further enhanced following interaction with the scaffolding protein termed M025 [7]. The best- characterized SPAK/OSR1 substrates comprise the SLC12A (solute carrier family 12) family of electroneutral CCCs (cation-Cl- cotransporters) [8–13]. These transporters regulate intracellular chloride concentration critical in controlling BP and cell volume homoeostasis [14, 15]. SPAK/OSR1 protein kinases drive chloride influx by phosphorylation and activating sodium- driven CCC members. These include the NCC (Na-Cl cotransporter) in the distal convoluted tubule of the kidney [11]. the NKCC2 (Na-K-2Cl cotransporter 2) in the thick ascending limb (TAL) of the kidney [13] and the ubiquitously expressed NKCC1[8–10]. SPAK/OSR1 also phosphorylate and inhibit potassium-driven CCCs that drive chloride efflux [12], which comprise four different K-Cl cotransporters (KCC1-KCC4) [15, 16]. This reciprocal regulation of Na+- and K+-driven CCCs by SPAK and OSR1 ensures that cellular Cl influx and efflux is tightly coordinated [15, 16].

The importance of the WNK signaling pathway is exemplified by its evolutionary conservation from worms to humans and that several Mendelian hypertension disorders in humans are caused by mutations in WNK pathway components [17, 18]. These include various mutations that lead to increased expression of the WNK1 and WNK4 genes causing PHAII [PseudoHypoAldosteronism type II, OMIM [19–24]]. A Gordon-like phenotype is also observed in mice that express a constitutively active SPAK in DCT1. These mice display thiazide-treatable hypertension and hyperkalemia, concurrent with NCC hyperphosphorylation [25]. Conversely, loss-of-function mutations in NCC and NKCC2 cause familial forms of hypotension and hypokalaemia termed Gitelman (OMIM #263800) and Bartter type 1 syndrome (OMIM #601678), respectively [26]. A mutation that ablates the key activating WNK-regulated SPAK/OSR1 phosphorylation site on NCC [T60M[11]] also causes Gitelman’s syndrome [27, 28]. Moreover, SPAK-knockout mice [29–31] or knock-in mice expressing a form of SPAK that cannot be activated by WNK kinase isoforms [32] exhibit low BP and are resistant to hypertension when crossed with animals bearing a PHAII-causing knock-in mutation that enhances WNK4 expression [33]. Genome-wide association studies have also identified intronic SNPs within the SPAK gene (STK39) that correlate with increased BP in humans [34]. Two commonly used drugs in medicine to lower high BP also target SPAK sodium-driven CCC substrates, namely thiazide diuretics (such as bendroflumethiazide) that inhibit NCC and the loop diuretics (such as furosemide) that inhibits NKCC2 [35, 36].

2. SPAK kinase

2.1. Discovery and characterization of the SPAK kinase

Ste20/SPS1-related proline/alanine rich kinase (SPAK) was discovered in the late 1990s as an unidentified band recognized by an antibody raised against PARP, the protein gene was cloned and found to be an unknown kinase [37]. The kinase was found to contain an N-terminal kinase domain which showed highest relationship to the Ste20 family of kinases. Furthermore N- terminal 71 amino acids are rich in proline and alanine, consequently Ushiro and coworkers first named the kinase proline-alanine-rich Ste20-related kinase (PASK), however in most subsequent publications the kinase is referred to as SPAK for the mouse isoform [38]. A colon specific splice variant of SPAK has been described, which is slightly shorter than the ubiquitous SPAK due to usage of two alternative splice donors in exon 1 and 7 [39]. Oxidative stress-response kinase-1 (OSR1) was identified in a large scale sequencing effort trying to map tumor suppressors within the human chromosome 3 [40]. OSR1 was named due to its similarity with the Ste20 kinase Ste20/oxidant stress response kinase 1 (SOK1). While the overall sequence identity of human SPAK and OSR1 is 68%, the kinase domains of the two kinases are highly similar and exhibit 88% sequence identity and 96% sequence similarity. Furthermore both kinases have 79% conserved C-terminal (CCT) domain that is unique to SPAK, OSR1 and orthologues of these two kinases. The presence of the unique CCT domain also meant that OSR1 and SPAK were placed in a distinct subfamily (GCK-VI) of the Ste20 kinases in the kinome [41]. Manning et al. placed OSR1 and SPAK in a subfamily called Fray, named after the Drosophila orthologue of OSR1 and SPAK [42]. Interestingly these two Fray or GCK-VI kinases evolutionary are not too distant from the WNK kinases.

Both SPAK and OSR1 kinases contain a putative nuclear localization signal and a caspase cleavage site between the kinase domain and the CCT domain. In unstimulated cultured cells full length SPAK exhibits diffuse localization whereas truncated constructs that mimic the caspase-cleaved SPAK targets is located in the nucleus [38, 39, 43]. Immunohistochemical studies of mouse choroid plexus and salivary glands show SPAK localization to be intense where NKCC1 is expressed: at the apical membrane of choroid plexus and basolateral membrane of salivary gland epithelial cells [8, 44]. SPAK overexpressed in Cos-7 cells re-localizes from a diffuse pattern to distinct membrane and vesicular staining patterns upon hypertonic stimulation [45]. Association of SPAK/OSR1 with plasma membrane was also clearly demonstrated by presence of the kinases in exosomes [46].

SPAK mRNA transcripts and protein are found abundantly in brain, salivary gland, pancreas, adrenal gland and testis, and to a lesser degree in heart, lung, kidney, stomach, intestine, ovary, thymus and spleen, and skeletal muscle [37, 38, 44]. OSR1 is more ubiquitously expressed and present in the tissues of the brain, heart, kidney, lung, spleen, testis, liver and skeletal muscle; likely indicative of the more global regulatory actions of OSR1, evidenced by the embryonically lethal constitutive OSR1-KO mouse models previously attempted [4, 32]. The SPAK knockout mouse is viable and shows no adverse behavioral phenotype [47]; however, other studies (Table 1) have shown SPAK knockout mice have low blood pressure [29]. This tissue specific expression correlates well with the expression patterns of the known substrates of OSR1 and SPAK, namely NCC, NKCC1 and NKCC2 which they directly phosphorylate at conserved key S/T residues to positively regulate transporter activity [5].

Table 1.

Mouse models in which SPAK have been genetically modified a

| Gene | Genetic modification | Effect on blood pressure |

Expression and activity of NCC |

Phenotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAK | SPAK−/− | ↓ with a Na+ depleted diet |

↓↓ | Hypokalemia when fed a K+-depleted diet Vasopressin induced NCC phosphorylation |

[30] |

| SPAK−/− | ND | ↓↓ | No NKCC2 phosphorylation Decreased NKCC2 |

[79] | |

| SPAK−/− | ND | ND | mediated Na+ reabsorption |

[80] | |

| SPAK−/− | ↓ | ↓ | [29] | ||

| SPAK−/− | ↓ | ↓↓ | Gitelman syndrome Na reabsorption in the TAL blunted, |

[29] | |

| SPAK−/− | ND | ND | vasopressin stimulation of NKCC2 intact |

[16] | |

| SPAKT243A/T243A | ↓ | ↓↓ | Gitelman syndrome | [32] | |

| SPAKL502A/L502A | ↓ | ↓↓ | Gitelman syndrome | [73] | |

| SPAKT243E/S383D | asl- sensitive hyper |

↓↓ | FHHt | [81] | |

| Wnk4- SPAK |

Wnk4D561A/+ | ↓ | ↑↑ | FHHt | [63] |

|

Wnk4D561A/+

SPAKT243A/ + |

Partial correction |

↑ | Partial correction |

[33] | |

| Wnk4D561/+ SPAK−/− | Normal | Normal | None | [82] |

↑ indicates increase; ↓indicates decrease. The number of up or down arrows denotes the relative magnitude of increase or decrease. Abbreviations: FHHt, familial hyperkalemic hypertension; ND, not determined.

There are three different isoforms of SPAK with the full-length isoform (FL-SPAK) being expressed ubiquitously with higher expression in the brain, heart, and testis [32, 44]. FL-SPAK is also expressed in the thick ascending limb (TAL) and distal convoluted tubules (DCT) of the kidney [30]. SPAK2, the second isoform, lacks the N-terminal PAPA box and a part of the kinase domain, and is also expressed ubiquitously. Kidney-specific SPAK (KS-SPAK) is the third isoform which is expressed mainly in the kidney, as the name suggests. Immunofluorescence studies showed that the FL-SPAK co-localized with NCC and NKCC2 at the DCT, whereas SPAK2 and KS-SPAK are more abundant in the TAL, the site of NKCC2 expression [30].

Both SPAK and OSR1 were shown to be able to autophosphorylate [37, 38, 43]. The crystal structure of the OSR1 kinase domain revealed that the kinase domain assumes a classical bi-lobal kinase fold similar to cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA). Furthermore the kinase domain forms a dimer and performs an activation segment exchange, where the two molecules swap α-helix EF [48, 49]. Whether this domain swapping actually occurs in the full length kinases, or whether it is a crystal artefact is still unclear. The kinase domain of OSR1 has however been shown to dimerize when overexpressed [10] and dimerization and domain swapping was shown to facilitate kinase activation [50].

2.2. SPAK as major regulator of CCCs

Biochemical experiments subsequently clarified the molecular mechanism by which the SPAK and OSR1 kinases activated by their upstream kinase WNKs, and to phosphorylate and stimulate N[K]CC activity [5, 6], or to phosphorylate and inhibit KCC activity [12]. Yeast-2-hybrid experiments have originally demonstrated that a unique 90 amino acid domain, the conserved C-terminal (“CCT”) docking domain, of SPAK and OSR1 bind a conserved peptide motif of their downstream targets [8]. The motifs are RFXV/I in the N-terminus of NCC, NKCC1, and NKCC2 [3, 51], RFMV motif in the N-terminus of KCC2A and KCC3A [12, 52]. However, KCC1 and KCC4 have HFTV or NFTV motif in their N-terminus which did not show interaction with SPAK/OSR1 [8, 53]. The CCT domain in SPAK/OSR1 is also required for the binding and activation of SPAK/OSR1 by the WNKs, which also possess RFXV/I motifs [54]. The structure of this specific CCT domain-peptide interaction was resolved by x-ray crystallography [6]. WNK isoforms, typically WNK1, WNK3 and WNK4, stimulate SPAK/OSR1 kinase activity by phosphorylating a conserved threonine residue (hSPAK Thr233, hOSR1 Thr185) within the SPAK/OSR1 catalytic T-loop motif, and a conserved Ser residue (hSPAK Ser373, hOSR1 Ser325) in the S-motif [32, 55]. Following hypertonic or hypotonic low-Cl- conditions, WNK isoforms, and hence SPAK/OSR1, are rapidly activated and phosphorylate a cluster of conserved Thr residues in the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain of the N[K]CCs [3]. This mechanism of CCC phosphorylation and activation is conserved for NCC, NKCC1, and NKCC2.

This activation model has been tested and confirmed using both biochemical experiments and functional experiments performed in heterologous expression systems, employing a variety of kinase-dead WNKs and SPAK/OSR1 mutants [4, 11, 51, 55]. A study done in mice showed that the WNK-SPAK/OSR1-NCC signaling cascade in the distal nephron has a circadian rhythm, with phosphorylated levels of NCC, SPAK and OSR1 increasing at the start of the active period (night for a mouse), while decreasing at the start of the resting period (day) [56]. It has also been shown that OSR1 and SPAK, in the presence of mouse protein-25 (M025, also called cab39) can form functional homo-dimers and hetero-dimers that are capable of self-activation by transphosphorylation, bypassing the required activation by WNK [48, 50]. M025 (Cab39) interacts with both SPAK and OSR1 to enhance their catalytic activities over 100-fold [7].

3. Role of SPAK in human physiology and disease

3.1. Targeting SPAK in essential hypertension

One quarter of adults in Western societies have elevated blood pressure (i.e., hypertension), which is a major risk factor for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, congestive heart failure, and end stage renal disease [57]. Hypertension is a tremendous burden on the budgets of health care systems worldwide; greater than $130 billion was spent on the treatment of this condition in 2010[57]. While lifestyle changes can modify hypertension, most patients require drugs to lower blood pressure. However, some patients on multi-drug regimens with currently available agents (e.g., hydrochlorothiazides, Ca2+ channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, loop diuretics, etc.) have poorly controlled disease or suffer from drug side effects, like K+ wasting. The treatment of hypertension is therefore an area of unmet clinical need, and the development of other efficacious agents that harbor fewer side effects is needed.

In the kidney, the WNK-SPAK/OSR1-mediated activation of NCC and NKCC2, which together mediate ~25% of renal salt reabsorption, is critical for extracellular volume levels, and this in turn influences blood pressure and electrolyte homeostasis. Of note, NCC is the target of thiazides, and NKCC2 the target of furosemide - these two drugs are some of the most common agents used in the treatment of hypertension and edematous states in clinical medicine today. The importance of the WNK-SPAK/OSR1-CCC pathway for renal physiology is exemplified most powerfully by human and mouse genetics. Consider: 1) mouse models strongly suggest that gain-of-function mutations in WNK1 and WNK4 and SPAK resulting in increased NCC- and NKCC2-activating phosphorylation cause hypertension in humans with PHAII [58–61]; 2) loss-of-function mutations in the upstream regulators of WNK1 and WNK4, KLHL3 and CUL3, also cause PHAII by increasing WNK1 and WNK4 expression due to a failure of protein degradation [21, 23, 24, 62–67]; 3) loss-of-function mutations in NCC and NKCC2 cause hypotension in humans with Gitelman’s and Bartter’s type 1 syndromes, respectively [68, 69]; 4) rare heterozygous mutations in NCC and NKCC2 alter renal NaCl handling and blood pressure variation in the general population, reduce blood pressure, and protect from development of hypertension [70]; 5) a mutation in NCC at a residue (Thr60Met) that abolishes the critical WNK-regulated SPAK-OSR1 activating phosphorylation event causes Gitelman’s syndrome in Asians [27, 28]; 6) genome-wide association studies of systolic and diastolic blood pressure reveals a strong disease association with common variants of SPAK [71, 72]; 7) SPAK knock-out mice exhibit reduced NCC activation [29] and knock-in mice expressing SPAK or OSR1 mutants that cannot be activated by WNK kinase isoforms exhibit reduced NCC and NKCC2 activating phosphorylation, hypotension, and are resistant to hypertension when crossed to transgenic knock-in mice bearing a PHAII-causing mutant WNK4 [32, 33, 73]; and 8) in distal nephron cells, WNK4 inhibits epithelia sodium channels (ENaC) [74], decreased ENaC expression compensates the increased NCC activity following inactivation of the kidney-specific isoform of WNK1 and prevents hypertension [75]. In oocytes, ENaC expression was significantly increased following coexpression of wild-type SPAK and constitutively active (T233E)SPAK, but not following coexpression of WNK insensitive (T233A)SPAK or catalytically inactive (D212A)SPAK [76].

Independently generated SPAK-KO [29, 47], kinase inactive SPAK-KI [32] and SPAK-CCT KI mouse models [73] have provided viable animals exhibiting sodium-wasting hypotensive phenotypes similar to Gitelman’s syndrome or chronic thiazide use (Table 1). These mice have significantly reduced expression of total and phospho-NCC (p-NCC), thus verifying the dominant role of SPAK in DCT regulation of NCC activity in vivo [11, 29, 47]. Notably SPAK- KO mice also exhibit an increase in TAL phospho-NKCC2 (p-NKCC2) which cannot be entirely attributed to an increase in phospho-OSR1 (p-OSR1), but rather may be explained by the emergence of a novel theory supporting a role for shorter sequence SPAK isoforms that exert a negative regulatory effect on CCCs reminiscent of the KS-WNK1/L-WNK1 story [30, 31]. Two of these isoforms that have been discovered in the kidney differ from full length SPAK (~60kDa) in predicted molecular weight and kinase activity; the first isoform SPAK2 (~49kDa) is missing part of the N-lobe of the kinase domain and presumed to be kinase impaired, while the second isoform KS-SPAK (~34kDa) is solely kidney specific and kinase inactive as the entire kinase domain is missing [31]. Note that, as an alternative mechanism to the downstream promoter, the role of a protease has also been proposed as a mechanism for producing the short KS-SPAK isoform [77]. As the CCT domain is intact in these isoforms it is presumed that they compete with full length SPAK and OSR1 for RFxV docking sites, thus inhibiting CCC activity. Another distinguishing factor is the differential expression of these isoforms along the nephron; of particular note in the TAL where SPAK2 and KS-SPAK is significantly higher than full length SPAK and also in the DCT where the inverse is true [30]. It was noted in oocyte and HEK-293 experiments that SPAK2 significantly decreased NKCC1 activity and that KS-SPAK attenuates levels of p-NCC, and perhaps in vivo at the TAL this abundance of negatively regulatory SPAK isoforms normally competes with the overwhelmingly OSR1 dominated regulation of NKCC2, while also muting positive SPAK regulation in this region. However, in the DCT full length SPAK is the dominant form expressed and can overcome the inhibitory effects of SPAK2 and KS-SPAK, evidenced by in vitro co-expression of full length SPAK significantly diminishing the inhibitory effects of SPAK2 on NKCC1 activity [30, 31]. Perhaps the most striking find in this newly discovered system of regulation was the presence of an isoform ratio switch in response to extracellular fluid (ECF) depletion; in which a low sodium diet decreased the abundance of KS-SPAK while increasing levels of full length SPAK, promoting sodium retention [31]. It is conceivable that complete SPAK-KO removes this negative competition and leaves OSR1 to increase NKCC2 activity uninhibited, thus accounting for increased pNKCC2 in these models [29, 47] and furthermore explaining the absence of change in NKCC2 activity in SPAK-KI mice, where the ratios of full length SPAK (although mutated), SPAK2, KS-SPAK and OSR1 are maintained [32].

Together, these data strongly suggest inhibition of the WNK-SPAK/OSR1 pathway might yield a new opportunity to develop improved anti-hypertensives. WNK-SPAK/OSR1 inhibitors are likely to have increased potency over either thiazides or furosemide alone, because they would simultaneously inhibit both NKCC2 and NCC activity. Additionally, WNK-SPAK/OSR1 inhibitors would likely spare K+ wasting and so may produce robust blood pressure lowering effects without the side effects of hypokalemia that is commonly associated with thiazides and loop diuretics [78]. How can the WNK-SPAK/OSR1 pathway be targeted to treat hypertension?

3.2. Intestine: secretory diarrhea/colitis

The WNK-SPAK pathway has only recently been explored in the regulation of ion transport across secretory epithelia in tissues other than the kidney, such as the skin, pancreas, and intestine. This investigation has stemmed in part from the original observations that, outside the kidney, WNK1 and WNK4 predominantly localized to polarized epithelia, including those lining the lumen of the hepatic biliary ducts, pancreatic ducts, sweat ducts, and colonic crypts [83, 84]. Epithelia in these tissues express channels and transporters that are responsible for transcellular Cl- and/or HCO3- ion movement from the blood, across the epithelial cell basolateral and apical membranes, and into the tissue lumen (e.g., sweat duct, pancreatic duct, or intestinal lumen). In doing so, these secretory epithelial cells therefore produce and maintain the homeostasis of sweat, pancreatic juice, intestinal mucus, and other bodily fluids. So far, the primary transport molecules in these tissues identified as targets of the WNKs-SPAK pathway include the Na+/HCO3- transporter NBCe1 (electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter 1); the Cl-/HCO3- exchanger family SLC26A; and the Cl- channel CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) [85–89].

The exocrine gland of the pancreas secretes a pancreatic juice rich in Cl- and HCO3- that also contains enzymes to digest dietary carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. WNK1-SPAK phosphorylation of NBCe1 and CFTR significantly inhibits ductal HCO3- secretion by reducing the plasma membrane expression of both NBCe1 and CFTR [88, 90]. Consistent with this, knock-down of several different WNK kinases in pancreatic ducts increases NBCe1 and CFTR- dependent ductal secretion. Interestingly, the NBCe1-B/CFTR activator inositol-1,4,5- trisphosphate (IP(3)) receptor-binding protein released with IP(3) (IRBIT) antagonizes the effects of the WNKs and SPAK on NBCe1 and CFTR by recruiting PP1 to the complex to dephosphorylate CFTR and NBCe1-B and stimulate their activities [88]. Given that the regulatory modalities in a conserved domain of NBCe1 may be present in CFTR and other transporters like the Slc26a6 sulfate transporter [87], and multiple ion transport proteins in secretory epithelia are regulated by PP1 and/or calcineurin, the WNK-SPAK and IRBIT-PP1 regulatory pathways of Cl- and HCO3- transport may serve to precisely tune the rate of epithelial secretion in response to physiological demands or pathological stimuli in numerous epithelia [86]. The relevance of this pathway for human physiology and disease was recently demonstrated in a large-scale human genetic study. CFTR variants that disrupt the WNK1-SPAK activation are associated with a selective, HCO3- defect in CFTR channel function and in turn affects organs that utilize CFTR for bicarbonate secretion (e.g. the pancreas), but do not cause typical CF [91, 92].

The colonic epithelium secretes mucus that is also rich in HCO3- and Cl-. Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are characterized by impaired immune regulation and epithelial barrier disruption. The mechanisms of the WNK-SPAK pathway in the regulation of colonic transport are less well characterized than in the pancreas. Targeted expression of SPAK has been shown to increase colonic epithelial permeability, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are elevated in induced experimental colitis, exacerbate this effect [39, 93]. In contrast, SPAK knockout mice exhibit higher intestinal barrier function and lower cytokine production in induced experimental colitis [94]. The correlated expression of SPAK with colon osmolality and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines has been linked to SP1 and NF-kB binding sites in the SPAK promoter [95]. These studies highlight the shared mechanisms and roles of the SPAK in regulating ion homeostasis in different tissues, and have implications for our understanding of CF and IBD, both of which are associated with abnormal epithelial transport. Interestingly, SPAK has also been implicated as potential therapeutic target for the glomerular disorder [96] due to the involvement of NF-κΒ and p38 MAPK in the nephrogenic effect of SPAK.

4. Strategies of SPAK inhibition

4.1. Inhibition of SPAK kinase catalytic activity

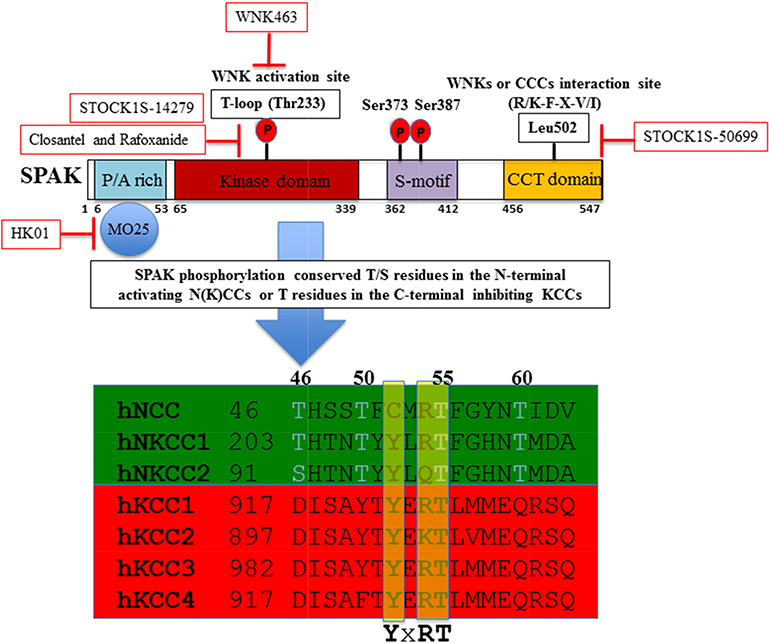

T-loop phosphorylation triggers activation of SPAK, as its mutation to Ala prevents activation [6, 97]. Knock-in mice in which the T-loop Thr residue in SPAK (Thr243) was mutated to Ala to prevent activation by WNK isoforms, and display significantly reduced blood pressure [32]. Therefore, a straightforward approach would be to target SPAK kinase, which is likely to function redundantly in the regulation of NCC and NKCC2, by generating SPAK-specific ATP- competitive kinase inhibitors. A SPAK kinase inhibitor would likely be more efficacious at blood pressure reduction over current agents that target either NCC or NKCC2 alone, since SPAK inhibition would coordinately reduce the activities of both NCC and NKCC2, as well as other less-characterized but no less important substrates of these kinases. However, Genomewide association studies of essential hypertension show a strong association with common variants of SPAK [34]. The strategy of targeting the ATP-binding site of the SPAK raises concern regarding the ability to develop sufficiently selective inhibitors that do not suppress other kinases. The development of Closantel, STOCK1S-14279 and Rafoxanide, ATP insensitive inhibitors, has introduced the possibility of developing inhibitors of WNKs signaling by binding to constitutively active or WNK-sensitive SPAK-T233E [98, 99] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The domain structure of SPAK and the phosphorylation target sites on NCC, NKCC1, NKCC2 and KCCs. OSR1 differs from SPAK in lacking the P/A rich (PAPA) domain. STOCK1S-50699 is a small-molecule inhibitor that blocks the interaction between SPAK/OSR1 and WNK by binding to the CCT domain [102]; Closantel is a small-molecule inhibitor that binds to constitutively active or WNK-sensitive(T233E)SPAK [98]; WNK463 inhibits of WNK1 catalytic activity [100]; and HK01 is an inhibitor of the M025 [105].

4.2. Direct WNK kinase inhibition

An alternative approach would be to target the atypical position of the catalytic lysine residue (Lys233 of WNK1) in the WNKs (recall, with no lysine = [K]), which is unique compared with all other proteins in the human kinome. This peculiarity could theoretically be exploited to create WNK-specific ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors. Indeed, Yamada et al. exploited these unique structural features to conduct a high throughput screen for inhibitors of WNK1 catalytic activity and discovered the first orally bioavailable pan-WNK kinase inhibitor, WNK463, which exhibits both low nanomolar affinity and high kinase selectivity (Figure 1). In spontaneously hypertensive rats, orally administered WNK463 significantly decreased blood pressure, facilitated a brisk diuresis, and reduced the phosphorylation of SPAK and OSR1 [100].

4.3. Inhibiting the WNK-SPAK interaction

As hypertension is a chronic largely asymptomatic condition it will be important to develop WNK or SPAK inhibitors that are sufficiently selective that do not cause intolerable side effects by inhibiting other signaling components. The strategy of targeting the ATP binding site of the SPAK or WNK, raises concern whether it will be possible to develop sufficiently selective inhibitors that do not suppress other kinases. The development of STOCK1S-50699 has introduced the possibility of developing inhibitors of SPAK signaling which target the CCT domain rather than the kinase domain (Figure 1). Crystallographic analysis demonstrates that the CCT domain adopts a unique fold not found in other proteins which possesses a pocket which forms a network of interactions with the conserved RFXV/I residues on WNKs and substrates [101]. A compound that binds to this structurally distinct CCT domain pocket and thus blocks RFXI/V binding motif, could be expected to display highly selectivity and not interfere with other signaling pathways.

Recently, Mori et al. utilized high-throughput screening of > 17,000 chemical compounds with fluorescent correlation spectroscopy and discovered inhibitors that disrupt the WNK(RFXV/I)- SPAK/OSR1(CCT) interaction which resulted in the identification of the aforementioned STOCK1S-50699 as well as a distinct compound termed STOCK2S-26016 [102]. We have confirmed that in vitro both compounds potently suppress CCT domain binding to RFXV motifs, but that in cellular studies we observed that only STOCK1S-50699 but not STOCK2S-26016 suppressed SPAK/OSR1 and NKCC1 phosphorylation induced by hypotonic low chloride conditions [12, 52]. Consistent with STOCK1S-50699 and STOCK2S-26016 being selective, they did not inhibit the activity of 139 different protein kinases tested [102]. Further experiments are required to study the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of STOCK1S-50699 to establish whether it could be deployed in live animals experiments. Ishigami-Yuasa et al. further applied screening their chemical library for WNK-SPAK binding inhibitors, and discovered novel inhibitors of this signal cascade from the 9-aminoacridine lead compound 1 [103]. Acridine derivatives were synthesized, such as several acridine-3-amide and 3-urea derivatives, show certain inhibition of the phosphorylation of NCC with doses of 10–20 mg/kg in mouse [103]. These initial studies offer encouragement that targeting the CCT domain could lead to the development of a novel class drugs that would be effective at lowering blood pressure. Given the phenotypes of human and mice with similar alterations in the WNK-SPAK pathway, a drug that suppressed SPAK might elicit particular potent anti-hypertensive effects due to its ability of suppressing renal NaCl reabsorption in a more coordinated and balanced manner than thiazide or loop diuretics, which only suppress activity of NCC (thiazide) or NKCC2 (loop diuretics) individually, while concurrently sparing renal K+ wasting - a common side effect of these diuretics. Also intriguing is suggestion that WNK-SPAK inhibition may elicit anti-hypertensive effects via a decrease in NKCC1-mediated vasoconstriction in blood vessels [29], though this hypothesis needs to be further explored. Such an action would offer synergistic effects on both renal and extra-renal targets for blood pressure reduction.

4.4. Inhibition of MO25, a key SPAK/OSR1 regulator

In addition, the closely related isoforms of the M025α and Μ025β scaffolding proteins operate as critical regulators of SPAK and OSR1 as well as a number of STE20 family protein kinases (e.g. MST and STRAD isoforms) [7, 104]. Therefore compounds that disrupt the activation of SPAK/OSR1 kinase activities by interfering with Μ025α/β binding could potentially represent a strategy for lowering blood pressure. To explore this approach, Kadri et al. developed a fluorescent polarization assay and used it in screening of a small in-house library of ~4000 compounds. This led to the identification of one compound-HK01-as the first small-molecule inhibitor of the MO25-dependent activation of SPAK and OSR1 in vitro [105] (Figure 1). This data confirm the feasibility of targeting this protein-protein interaction by small-molecule compounds and highlights their potential to modulate ion co-transporters and thus cellular electrolyte balance.

5. Expert opinion

The importance of coordinating cellular Cl- influx and efflux in renal epithelia and neurons is well known [106, 107]. The finding that SPAK/OSR1 kinases phosphorylate and thereby trigger activation of the Na+-driven, Cl- influx CCCs (NKCC1, NKCC2 and NCC) and also phosphorylate and inhibit K+-driven, Cl- efflux CCCs (KCC1, KCC2, KCC3 and KCC4) helps explain how the CCCs are normally reciprocally and coordinately controlled to achieve homeostasis in multiple tissues. This coordinated and potent mechanism, with opposite effects on the main Cl- influx and Cl- efflux mediators involved in cellular Cl- homeostasis, is of obvious interest to drug development. The WNK-SPAK-CCC pathway is critically important for normal human physiology, and humans and mice with mutations in this pathway have illustrated the potential effects of targeting this pathway for therapeutic benefit in human diseases. The current data suggest that this mechanism is most specifically and powerfully druggable by the targeting of 1) WNK catalytic lysine residue, 2) the CCT domain within SPAK, which interferes with WNK kinase activation, 3) SPAK with inhibitors able to bind to constitutively active or WNK- sensitive SPAK-T223E and 4) M025 interacts with SPAK. A disease most obviously amenable to inhibition of the WNK-SPAK/ OSR1 pathway would include essential hypertension, one of the most common diseases of the industrialized world. In addition, given the recent enthusiasm for the discovery of KCC2 activators to enhance neuronal Cl- extrusion in diseases featuring GABAergic disinhibition, exploring the effects of WNK-SPAK/OSR1 inhibition in seizures, neuropathic pain, spasticity, and other diseases featuring neuronal excitability seems like a very compelling idea. SPAK inhibition enhances cellular Cl- extrusion by concurrently inhibiting NKCC1-mediated Cl- influx via NKCC1 and activating KCC-mediated Cl- efflux via the KCCs Therefore, targeting SPAK kinase might also prevent inhibition of feedback on other CCCs or molecules that aim to equilibrate ion gradients, offering a coordinated, multivalent, and sustained effect.

Article highlights.

Discovery and characterization of the SPAK kinase

SPAK as major regulator of CCCs

Targeting SPAK in essential hypertension

Targeting SPAK in secretory diarrhea/colitis

Strategies of SPAK inhibition

Acknowledgments

Funding

This paper was supported in part by NIH grant R21GM118944 to E. Delpire; and the March of Dimes Basil O’Connor Award, Simons Foundation SFARI Award and NIH award (NRCDP K12) to K. T. Kahle.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Bibliography

- 1.Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:28–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen P, Alessi DR. Kinase drug discovery--what’s next in the field? ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson C, Alessi DR. The regulation of salt transport and blood pressure by the WNK-SPAK/OSR1 signalling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delpire E, Gagnon KB. SPAK and OSR1: STE20 kinases involved in the regulation of ion homoeostasis and volume control in mammalian cells. Biochem J. 2008;409:321–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriguchi T, Urushiyama S, Hisamoto N, et al. WNK1 regulates phosphorylation of cation-chloride-coupled cotransporters via the STE20-related kinases, SPAK and OSR1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42685–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. •.Vitari AC, Deak M, Morrice NA, et al. The WNK1 and WNK4 protein kinases that are mutated in Gordon’s hypertension syndrome phosphorylate and activate SPAK and OSR1 protein kinases. Biochem J. 2005;391:17–24. Refs 5 and 6 - WNK1 and SPAK/OSR1 mediate the hypotonic stress signaling pathway to the transporters (NKCC1, NKCC2, and NCC) and may provide insights into the mechanisms by which WNK1 regulates ion balance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. •.Filippi BM, de los Heros P, Mehellou Y, et al. MO25 is a master regulator of SPAK/OSR1 and MST3/MST4/YSK1 protein kinases. EMBO J. 2011;30:1730–41. First time demonstrates MO25 as a key regulator of SPAK kinases in vitro, suggesting that MO25 inhibitors would be effective at reducing BP by lowering SPAK activity and phosphorylation as well as expression of NCC and NKCC2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piechotta K, Lu J, Delpire E. Cation chloride cotransporters interact with the stress-related kinases Ste20-related proline-alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) and oxidative stress response 1 (OSR1). J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50812–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gagnon KB, England R, Delpire E. Volume sensitivity of cation-Cl- cotransporters is modulated by the interaction of two kinases: Ste20-related proline-alanine-rich kinase and WNK4. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C134–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anselmo AN, Earnest S, Chen W, et al. WNK1 and OSR1 regulate the Na+, K+, 2C1- cotransporter in HeLa cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10883–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson C, Rafiqi FH, Karlsson HK, et al. Activation of the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl- cotransporter by the WNK-regulated kinases SPAK and OSR1. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:675–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. •.de Los Heros P, Alessi DR, Gourlay R, et al. The WNK-regulated SPAK/OSR1 kinases directly phosphorylate and inhibit the K+-C1- co-transporters. Biochem J. 2014;458:559–73. WNK-regulated SPAK/OSR1 act as direct phosphorylators and major regulators of the KCC isoforms, which explains how activation of the WNK signalling pathway can co-ordinately regulate Cl- influx and efflux by reciprocally controlling the SLC12A family N[K]CC and KCC isoforms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson C, Sakamoto K, de los Heros P, et al. Regulation of the NKCC2 ion cotransporter by SPAK-OSR1-dependent and -independent pathways. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:789–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gagnon KB, Delpire E. Physiology of SLC12 transporters: lessons from inherited human genetic mutations and genetically engineered mouse knockouts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C693–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arroyo JP, Kahle KT, Gamba G. The SLC12 family of electroneutral cation-coupled chloride cotransporters. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:288–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahle KT, Rinehart J, Lifton RP. Phosphoregulation of the Na-K-2Cl and K-Cl cotransporters by the WNK kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:1150–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahle KT, Ring AM, Lifton RP. Molecular physiology of the WNK kinases. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:329–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alessi DR, Zhang J, Khanna A, et al. The WNK-SPAK/OSR1 pathway: master regulator of cation-chloride cotransporters. Sci Signal. 2014;7:re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson FH, Disse-Nicodeme S, Choate KA, et al. Human hypertension caused by mutations in WNK kinases. Science. 2001;293:1107–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyden LM, Choi M, Choate KA, et al. Mutations in kelch-like 3 and cullin 3 cause hypertension and electrolyte abnormalities. Nature. 2012;482:98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohta A, Schumacher FR, Mehellou Y, et al. The CUL3-KLHL3 E3 ligase complex mutated in Gordon’s hypertension syndrome interacts with and ubiquitylates WNK isoforms: disease-causing mutations in KLHL3 and WNK4 disrupt interaction. Biochem J. 2013;451:111–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schumacher FR, Sorrell FJ, Alessi DR, et al. Structural and biochemical characterization of the KLHL3-WNK kinase interaction important in blood pressure regulation. Biochem J. 2014;460:237–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakabayashi M, Mori T, Isobe K, et al. Impaired KLHL3-mediated ubiquitination of WNK4 causes human hypertension. Cell Rep. 2013;3:858–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louis-Dit-Picard H, Barc J, Trujillano D, et al. KLHL3 mutations cause familial hyperkalemic hypertension by impairing ion transport in the distal nephron. Nat Genet 2012;44:456–60, S1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grimm PR, Coleman R, Delpire E, et al. Constitutivelyactive SPAK causes hyperkalemia by activating NCC and remodeling distal tubules. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;pii: ASN.2016090948. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016090948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon DB, Nelson-Williams C, Bia MJ, et al. Gitelman’s variant of Bartter’s syndrome, inherited hypokalaemic alkalosis, is caused by mutations in the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter. Nat Genet. 1996;12:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin SH, Shiang JC, Huang CC, et al. Phenotype and genotype analysis in Chinese patients with Gitelman’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2500–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shao L, Ren H, Wang W, et al. Novel SLC12A3 mutations in Chinese patients with Gitelman’s syndrome. Nephron Physiol. 2008;108:p29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. •.Yang SS, Lo YF, Wu CC, et al. SPAK-knockout mice manifest Gitelman syndrome and impaired vasoconstriction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1868–77. First genetic evidence to show that SPAK-null mice have defects of NCC in the kidneys and NKCC1 in the blood vessels, leading to hypotension through renal salt wasting and vasodilation, suggesting that SPAK may be a promising target for antihypertensive therapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCormick JA, Mutig K, Nelson JH, et al. A SPAK isoform switch modulates renal salt transport and blood pressure. Cell Metab. 2011;14:352–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grimm PR, Taneja TK, Liu J, et al. SPAK isoforms and OSR1 regulate sodium-chloride cotransporters in a nephron-specific manner. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:37673–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. •.Rafiqi FH, Zuber AM, Glover M, et al. Role of the WNK-activated SPAK kinase in regulating blood pressure. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:63–75. First in vivo mouse evidence to establish that SPAK kinase plays an important role in controlling blood pressure in mammals, suggesting that SPAK kinase inhibitors would be effective at reducing BP by lowering phosphorylation as well as expression of NCC and NKCC2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiga M, Rafiqi FH, Alessi DR, et al. Phenotypes of pseudohypoaldosteronism type II caused by the WNK4 D561A missense mutation are dependent on the WNK-OSR1/SPAK kinase cascade. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1391–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, O’Connell JR, McArdle PF, et al. Whole-genome association study identifies STK39 as a hypertension susceptibility gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:226–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gordon RD, Hodsman GP. The syndrome of hypertension and hyperkalaemia without renal failure: long term correction by thiazide diuretic. Scott Med J. 1986;31:43–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon RD, Klemm SA, Tunny TJ, et al. Gordon’s syndrome: A sodium-volume- dependent form of hypertension with a genetic basis In: Laragh JH, Brenner BM, eds. Hypertension: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. New York: Raven Press; 1995:2111–23. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ushiro H, Tsutsumi T, Suzuki K, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel Ste20-related protein kinase enriched in neurons and transporting epithelia. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;355:233–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnston AM, Naselli G, Gonez LJ, et al. SPAK, a STE20/SPS1-related kinase that activates the p38 pathway. Oncogene. 2000;19:4290–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. •.Yan Y, Nguyen H, Dalmasso G, et al. Cloning and characterization of a new intestinal inflammation-associated colonic epithelial Ste20-related protein kinase isoform.Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1769:106–16. This paper collectively suggests that pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling may induce expression of this novel SPAK isoform in intestinal epithelia, triggering the signaling cascades that govern intestinal inflammation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamari M, Daigo Y, Nakamura Y. Isolation and characterization of a novel serine threonine kinase gene on chromosome 3p22–21.3. J Hum Genet 1999;44:116–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delpire E The mammalian family of sterile 20p-like protein kinases. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:953–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, et al. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen W, Yazicioglu M, Cobb MH. Characterization of OSR1, a member of the mammalian Ste20p/germinal center kinase subfamily. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piechotta K, Garbarini N, England R, et al. Characterization of the interaction of the stress kinase SPAK with the Na+-K+−2Cl- cotransporter in the nervous system: evidence for a scaffolding role of the kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52848–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsutsumi T, Kosaka T, Ushiro H, et al. PASK (proline-alanine-rich Ste20-related kinase] binds to tubulin and microtubules and is involved in microtubule stabilization. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;477:267–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koumangoye R, Delpire E. The Ste20 kinases SPAK and OSR1 travel between cells through exosomes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2016;311:C43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geng Y, Hoke A, Delpire E. The Ste20 kinases Ste20-related proline-alanine-rich kinase and oxidative-stress response 1 regulate NKCC1 function in sensory neurons. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14020–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee SJ, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. Crystal structure of domain-swapped STE20 OSR1 kinase domain. Protein Sci. 2009;18:304–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Villa F, Deak M, Alessi DR, et al. Structure of the OSR1 kinase, a hypertension drug target. Proteins. 2008;73:1082–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ponce-Coria J, Gagnon KB, Delpire E. Calcium-binding protein 39 facilitates molecular interaction between Ste20p proline alanine-rich kinase and oxidative stress response 1 monomers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C1198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. ••.Vitari AC, Thastrup J, Rafiqi FH, et al. Functional interactions of the SPAK/OSR1 kinases with their upstream activator WNK1 and downstream substrate NKCC1. Biochem J. 2006;397:223–31. This paper establishes that the CCT domain functions as a multipurpose docking site, enabling SPAK/OSR1 to interact with substrates (NKCC1) and activators (WNK1/WNK4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. •.Zhang J, Gao G, Begum G, et al. Functional kinomics establishes a critical node of volume-sensitive cation-Cl- cotransporter regulation in the mammalian brain. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35986 This paper concludes that WNK3-SPAK is an integral component of the long-sought “Cl-/volume-sensitive kinase” of the cation-Cl- cotransporters, and functions as a molecular rheostat of cell volume in the mammalian brain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kahle KT, Delpire E. Kinase-KCC2 coupling: Cl- rheostasis, disease susceptibility, therapeutic target. J Neurophysiol. 2016;115:8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. ••.Thastrup JO, Rafiqi FH, Vitari AC, et al. SPAK/OSR1 regulate NKCC1 activity: analysis of WNK isoform interactions and activation by T-loop trans-autophosphorylation Biochem J. 2012;441:325–37. This paper provides novel insights into the WNK signal transduction pathway and provide genetic evidence confirming the essential role that SPAK/OSR1 play in controlling NKCC1 function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ponce-Coria J, San-Cristobal P, Kahle KT, et al. Regulation of NKCC2 by a chloride sensing mechanism involving the WNK3 and SPAK kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8458–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Susa K, Sohara E, Isobe K, et al. WNK-OSR1/SPAK-NCC signal cascade has circadian rhythm dependent on aldosterone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;427:743–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. Forecasting the Future of Cardiovascular Disease in the United States A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vidal-Petiot E, Elvira-Matelot E, Mutig K, et al. WNK1-related Familial Hyperkalemic Hypertension results from an increased expression of L-WNK1 specifically in the distal nephron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:14366–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bergaya S, Faure S, Baudrie V, et al. WNK1 regulates vasoconstriction and blood pressure response to alpha 1-adrenergic stimulation in mice. Hypertension. 2011;58:439–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Castaneda-Bueno M, Cervantes-Perez LG, Vazquez N, et al. Activation of the renal Na+:C1- cotransporter by angiotensin II is a WNK4-dependent process. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:7929–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takahashi D, Mori T, Nomura N, et al. WNK4 is the major WNK positively regulating NCC in the mouse kidney. Biosci Rep. 2014;34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glover M, Ware JS, Henry A, et al. Detection of mutations in KLHL3 and CUL3 in families with FHHt (familial hyperkalaemic hypertension or Gordon’s syndrome). Clin Sci (Lond). 2014;126:721–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Susa K, Kita S, Iwamoto T, et al. Effect of heterozygous deletion of WNK1 on the WNK- OSR1/ SPAK-NCC/NKCC1/NKCC2 signal cascade in the kidney and blood vessels. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2012;16:530–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anderica-Romero AC, Escobar L, Padilla-Flores T, et al. Insights in cullin 3/WNK4 and its relationship to blood pressure regulation and electrolyte homeostasis. Cell Signal. 2014;26:1166–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mori Y, Wakabayashi M, Mori T, et al. Decrease of WNK4 ubiquitination by disease-causing mutations of KLHL3 through different molecular mechanisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;439:30–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsuji S, Yamashita M, Unishi G, et al. A young child with pseudohypoaldosteronism type II by a mutation of Cullin 3. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shibata S, Zhang J, Puthumana J, et al. Kelch-like 3 and Cullin 3 regulate electrolyte homeostasis via ubiquitination and degradation of WNK4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:7838–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simon DB, Karet FE, Hamdan JM, et al. Bartter’s syndrome, hypokalaemic alkalosis with hypercalciuria, is caused by mutations in the Na-K-2CI cotransporter NKCC2. Nat Genet. 1996;13:183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simon DB, Nelson-Williams C, Johnson Bia M, et al. Gitelman’s variant of Barter’s syndrome, inherited hypokalaemic alkalosis, is caused by mutations in the thiazide- sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter. Nat Genet. 1996;12:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ji W, Foo JN, O’Roak BJ, et al. Rare independent mutations in renal salt handling genes contribute to blood pressure variation. Nat Genet. 2008;40:592–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adeyemo A, Gerry N, Chen G, et al. A genome-wide association study of hypertension and blood pressure in African Americans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang H, Ye L, Wang Q, et al. A meta-analytical assessment of STK39 three well-defined polymorphisms in susceptibility to hypertension. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. •.Zhang J, Siew K, Macartney T, et al. Critical role of the SPAK protein kinase CCT domain in controlling blood pressure. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:4545–58. First genetic evidence to show that SPAK CCT domain defective knock-in mice displayed markedly reduced SPAK activity and phosphorylation of NCC and NKCC2 co-transporters at the residues phosphorylated by SPAK have, leading to hypotension through renal salt wasting, suggesting that CCT domain inhibitors would be effective at reducing BP by lowering phosphorylation as well as expression of NCC and NKCC2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yu L, Cai H, Yue Q, et al. WNK4 inhibition of ENaC is independent of Nedd4–2-mediated ENaC ubiquitination. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305:F31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hadchouel J, Soukaseum C, Busst C, et al. Decreased ENaC expression compensates the increased NCC activity following inactivation of the kidney-specific isoform of WNK1 and prevents hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18109–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ahmed M, Salker MS, Elvira B, et al. SPAK Sensitive Regulation of the Epithelial Na Channel ENaC. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2015;40:335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Markadieu N, Rios K, Spiller BW, et al. Short forms of Ste20-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) in the kidney are created by aspartyl aminopeptidase (Dnpep)-mediated proteolytic cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:29273–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Greenberg A Diuretic complications. Am J Med Sci. 2000;319:10–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Saritas T, Borschewski A, McCormick JA, et al. SPAK differentially mediates vasopressin effects on sodium cotransporters. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:407–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheng CJ, Yoon J, Baum M, et al. STE20/SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) is critical for sodium reabsorption in isolated, perfused thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;308:F437–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grimm PR, Coleman R, Delpire E, et al. Enhanced NCC function due to constitutively active SPAK causes hyperkalemia by inducing distal tubule remodeling. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017:In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chu PY, Cheng CJ, Wu YC, et al. SPAK deficiency corrects pseudohypoaldosteronism II caused by WNK4 mutation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Choate KA, Kahle KT, Wilson FH, et al. WNK1, a kinase mutated in inherited hypertension with hyperkalemia, localizes to diverse Cl- -transporting epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:663–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kahle KT, Gimenez I, Hassan H, et al. WNK4 regulates apical and basolateral Cl- flux in extrarenal epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2064–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mendes AI, Matos P, Moniz S, et al. Antagonistic regulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator cell surface expression by protein kinases WNK4 and spleen tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4076–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hong JH, Park S, Shcheynikov N, et al. Mechanism and synergism in epithelial fluid and electrolyte secretion. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:1487–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hong JH, Yang D, Shcheynikov N, et al. Convergence of IRBIT, phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate, and WNK/SPAK kinases in regulation of the Na+-HC03- cotransporters family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4105–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang D, Li Q, So I, et al. IRBIT governs epithelial secretion in mice by antagonizing the WNK/SPAK kinase pathway. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:956–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang CL, Liu X, Paliege A, et al. WNK1 and WNK4 modulate CFTR activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:535–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang D, Shcheynikov N, Zeng W, et al. IRBIT coordinates epithelial fluid and HC03- secretion by stimulating the transporters pNBC1 and CFTR in the murine pancreatic duct. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Park HW, Nam JH, Kim JY, et al. Dynamic Regulation of CFTR Bicarbonate Permeability by [Cl-](i) and Its Role in Pancreatic Bicarbonate Secretion. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:620–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.LaRusch J, Jung J, General IJ, et al. Mechanisms of CFTR functional variants that impair regulated bicarbonate permeation and increase risk for pancreatitis but not for cystic fibrosis. PLoS Genet. 2014;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yan Y, Laroui H, Ingersoll SA, et al. Overexpression of Ste20-related proline/alanine- rich kinase exacerbates experimental colitis in mice. J Immunol. 2011;187:1496–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang Y, Viennois E, Xiao B, et al. Knockout of Ste20-like proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) attenuates intestinal inflammation in mice. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1617–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yan Y, Dalmasso G, Nguyen HT, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB is a critical mediator of Ste20-like proline-/alanine-rich kinase regulation in intestinal inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1013–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lin TJ, Yang SS, Hua KF, et al. SPAK plays a pathogenic role in IgA nephropathy through the activation of NF-kappaB/MAPKs signaling pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;99:214–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zagorska A, Pozo-Guisado E, Boudeau J, et al. Regulation of activity and localization of the WNK1 protein kinase by hyperosmotic stress. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:89–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. •.Kikuchi E, Mori T, Zeniya M, et al. Discovery of Novel SPAK Inhibitors That Block WNK Kinase Signaling to Cation Chloride Transporters. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1525–36. This paper reports one small-molecule compound (Stock 1S-14279) and an antiparasitic agent (Closantel) that inhibited SPAK-regulated phosphorylation and activation of NCC and NKCC1 in vitro and in mice, in an ATP-insensitive manner. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alamri MA, Kadri H, Alderwick LJ, et al. Rafoxanide and Closantel inhibit SPAK and OSR1 kinases by binding to a highly conserved allosteric site on their C-terminal domains. ChemMedChem. 2017;12:639–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. ••.Yamada K, Park HM, Rigel DF, et al. Small-molecule WNK inhibition regulates cardiovascular and renal function. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:896–8. The paper reports the development of the first orally bioavailable pan-WNK- kinase inhibitor WNK463 that exploits unique structural properties of the WNKs to achieve high affinity and kinase selectivity as a potential therapeutic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. •.Villa F, Goebel J, Rafiqi FH, et al. Structural insights into the recognition of substrates and activators by the OSR1 kinase. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:839–45. Crystallographic analysis demonstrates that the CCT domain of SPAK/OSR1 adopts a unique fold not found in other proteins and has a pocket that forms a network of interactions with the conserved RFXV/I residues on WNKs and substrates. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. •.Mori T, Kikuchi E, Watanabe Y, et al. Chemical library screening for WNK signalling inhibitors using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biochem J. 2013;455:339–45. This paper reports the screening of WNK signalling inhibitors that reproducibly disrupted the binding of WNK to SPAK, therefore result in the inhibition of hypotonicity-induced activation of WNK and the phosphorylation of SPAK and its downstream transporters NKCC1 and NCC in cultured cell lines. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. ••.Ishigami-Yuasa M, Watanabe Y, Mori T, et al. Development of WNK signaling inhibitors as a new class of antihypertensive drugs. Bioorg Med Chem. 2017; 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.05.034. This paper reports the screening of a new class of antihypertensive inhibitors of the WNK- OSR1/SPAK-NCC cascade. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mehellou Y, Alessi DR, Macartney TJ, et al. Structural insights into the activation of MST3 by MO25. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;431:604–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. •.Kadri H, Alamri MA, Navratilova IH, et al. Towards the development of small-molecule MO25 binders as potential indirect SPAK/OSR1 kinase inhibitors. Chembiochem. 2016;18: 460–65 This paper reports the first small-molecule inhibitor (HK01) of the MO25- dependent activation of SPAK and OSR1 in vitro from a compound library. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gamba G Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of electroneutral cation-chloride cotransporters. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:423–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Adragna NC, Di Fulvio M, Lauf PK. Regulation of K-Cl cotransport: from function to genes. J Membr Biol. 2004;201:109–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]