Abstract

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) catalyzes the formation of prostaglandins, which are involved in immune regulation, vascular function, and synaptic signaling. COX-2 also inactivates the endogenous cannabinoid (eCB) 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) via oxygenation of its arachidonic acid backbone to form a variety of prostaglandin glyceryl esters (PG-Gs). Although this oxygenation reaction is readily observed in vitro and in intact cells, detection of COX-2-derived 2-AG oxygenation products has not been previously reported in neuronal tissue. Here we show that 2-AG is metabolized in the brain of transgenic COX-2-overexpressing mice and mice treated with the lipopolysaccharide to form multiple species of PG-Gs that are detectable only when monoacylglycerol lipase is concomitantly blocked. Formation of these PG-Gs is prevented by acute pharmacological inhibition of COX-2. These data provide evidence that neuronal COX-2 is capable of oxygenating 2-AG to form a variety PG-Gs in vivo and support further investigation of the physiological functions of PG-Gs.

Keywords: Endocannabinoid, prostaglandin glyceryl esters, cannabinoid, monoacylglycerol lipase, Lumiracoxib, lipopolysaccharide, prostamide

Introduction

Endogenous cannabinoids (eCBs) are a class of bioactive lipid signaling molecules implicated in a variety of physiological processes including appetite regulation, energy homeostasis, cardiovascular function, motivation, anxiety, and sleep1–5. Within neurons, the eCBs 2-AG and anandamide (AEA) are generated in an activity-dependent manner and serve primarily as retrograde signaling molecules that reduce presynaptic neurotransmitter release via activation of type-1 cannabinoid receptors6. eCBs may also have direct postsynaptic effects on membrane potential and neuronal excitability7, 8. Despite these well-established roles of eCBs, how these lipids are metabolized via non-canonical routes to generate potentially distinct signaling molecules is an active area of investigation.

The exact biosynthesis of AEA is poorly understood, but AEA is primarily metabolized by neuronal fatty-acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) to arachidonic acid (AA)9. However, COX-2 can also metabolize AEA to form prostaglandin ethanolamides (PG-EAs; prostamides)10. The prostamides include PGE2-EA, PGD2-EA, and PGF2α-EA and have been previously detected in vivo, supporting the notion that COX-2 serves as a non-canonical eCB metabolic enzyme. For example, PGF2α-EA is detected upon COX-2 upregulation in both rodent dorsal spinal neurons after carrageenan-induced knee inflammation11 and in preadipocyte cells where PGF2α-EA acts to prevent adiopogenesis12. It has been suggested that the ability to detect prostamides in vivo may be facilitated by their relative metabolic stability and lack of metabolism by FAAH13.

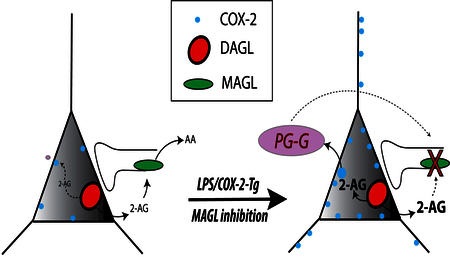

2-AG is a highly abundant eCB that mediates retrograde inhibition at central glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses14. Synaptic 2-AG is generated via the sequential actions of phospholipase C and diacylglycerol lipase-α, in response to a variety of activity-dependent mechanisms. In addition to its signaling functions, 2-AG is thought to be the most common source of AA for PG production in the CNS15. The synaptic actions of 2-AG are terminated predominantly via monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL), but also by α/β-hydrolase domain 6 and 12, as well as COX-216. Indeed, 2-AG is efficiently oxygenated by COX-2 in vitro to form prostaglandin glyceryl esters (PG-Gs), and 2-AG-mediated retrograde synaptic inhibition can be enhanced by pharmacological inhibition of COX-210,17–20. Despite being detected in macrophages following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) administration21–23 and in inflamed rat hindpaw24, COX-2-derived oxidative metabolites of 2-AG in brain have remained elusive. It is possible that PG-Gs are hydrolytically unstable in vivo or rapidly further metabolized, and thus have eluded detection. Given that PG-Gs have been recently identified as endogenous agonists of P2Y6 receptors25 and implicated as neuronal signaling molecules16 and pain modulators in the periphery24, a clearer understanding of the conditions under which PG-Gs are formed is needed.

Here we use an LPS model of neuroinflammation, a transgenic COX-2 overexpression model, and pharmacological approaches combined with stable isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to detect and quantify PG-G formation in mouse brain for the first time. These data provide evidence that neuronal COX-2 can produce PG-Gs in the brain when 2-AG levels are elevated via MAGL inhibition and provide direct support for the contention that neuronal COX-2 metabolizes 2-AG in vivo.

Results and Discussion

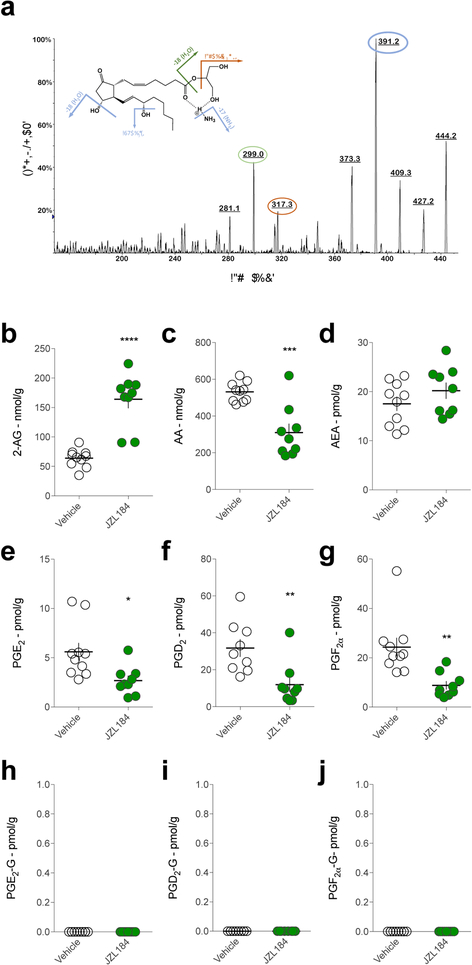

We first optimized our analytical detection of PG-Gs by LC/MS/MS using deuterated PGE2-G and PGD2-G as authentic standards. PGE2-G, PGD2-G and PGF2α-G were identified and quantified by LC-MS/MS analysis. These three analytes and the internal standards (PGE2-G-d5 and PGF2α-G-d5) were ionized by complexation with the ammonium cation, resulting in an [M+NH4]+ complex. Multiple product ions were observed when this complex was subjected to collision induced dissociation (CID). For example, the CID spectrum of the [PGE2-G+NH4]+ complex (m/z = 444.3) is shown in Fig. 1a, where the product ions at m/z 391.2, 317.3, and 299.0 are observed. Fragmentation of the [PGD2-G+NH4]+ complex gives a similar spectrum (not shown). For both PGE2-G and PGD2-G, the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) transition m/z 444.2 – 391.1 was used for quantitative analysis as this transition gave the greatest signal:noise ratio. Table S1 gives the SRM transitions for all analytes reported here. The chromatographic system we employed here was able to resolve the sn-1 and sn-2 isomers of PGE2-G, PGD2-G and PGF2α-G (Fig. S1). PG-Gs are monoacylglycerols and thus will undergo isomerization from the presumed original sn-2 conformation to the thermodynamically favored sn-1 conformation. Importantly, LC-MS/MS analysis using alternative SRM transitions (m/z 444.2 – 317.1 & 444.2 – 299.0) generated nearly identical chromatograms to that generated by m/z 444.2 – 391.1 transition, providing compelling support for our accurate and reliable detection of authentic PG-Gs using our analytical approach (Fig. S2 a–b).

Figure. 1. PG-Gs are not detected in C57/Bl6J mouse brain after MAGL inhibition.

(a) CID spectra of PGE2-G. Upon CID, the ammonium complex of PGE2-G (m/z 444) undergoes sequential loss of NH3 and two molecules of H2O to generate the product ions at m/z 427, 409 and 391, respectively. Subsequently, m/z 391 species will undergo a loss of H2O and C3H6 O2 (74 Da) – in either order – to generate the product ions at m/z 373, 317 and 299. Circled peak 391 was used for quantitative analysis while 299 and 317 were used for confirmatory analysis (see Fig. S1). (b-d) Effects of JZL184 on 2-AG, AA, and AEA levels in mouse brain. (e-g) Effects of JZL184 on prostaglandin levels in mouse brain. (h-j) Effects of JZL184 on PG-G levels in mouse brain, relative to vehicle-treated mice. Each point (circle) represents a biological replicate (one mouse). Veh n=10, JZL184 n=9. Error bars represent S.E.M. * p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 by t-test.

To determine whether PG-Gs are present in mouse brain, we extracted lipids from one hemisphere of C57/Bl6J mouse brains and analyzed them for PG-G levels. Under these conditions, we were unable to detect any native PG-G species, consistent with our previous attempts and previously published studies20, 24 (Fig. 1h–j, vehicle-treated mice). We hypothesized that COX-2-mediated generation of PG-Gs might be substrate-limited, and thus the lack of detectable PG-Gs may be due to insufficient levels of 2-AG available for oxygenation by COX-2. To test this hypothesis, we administered the MAGL inhibitor JZL184 (40 mg/kg) to elevate 2-AG levels. As expected, 2-AG levels were significantly elevated after JZL184 treatment, whereas free AA levels were reduced, and AEA levels were unchanged (Fig. 1b–d). Also, consistent with previous studies, levels of PGs were reduced in JZL184-treated mice relative to vehicle-treated mice15 (Fig. 1e–g). Despite elevated 2-AG levels present in the brains of JZL184-treated mice, we were still unable to detect PG-Gs under these conditions (Fig. 1h–j). It has been suggested that PG-Gs are metabolized by MAGL26, therefore the lack of detectable PG-Gs after JZL184 treatment was quite surprising and suggests that elevation of 2-AG combined with PG-G degradation inhibition may not be sufficient for generation of detectable levels of PG-Gs. Alternatively, the levels of 2-AG may not be sufficiently high after JZL184 treatment to allow for PG-G formation.

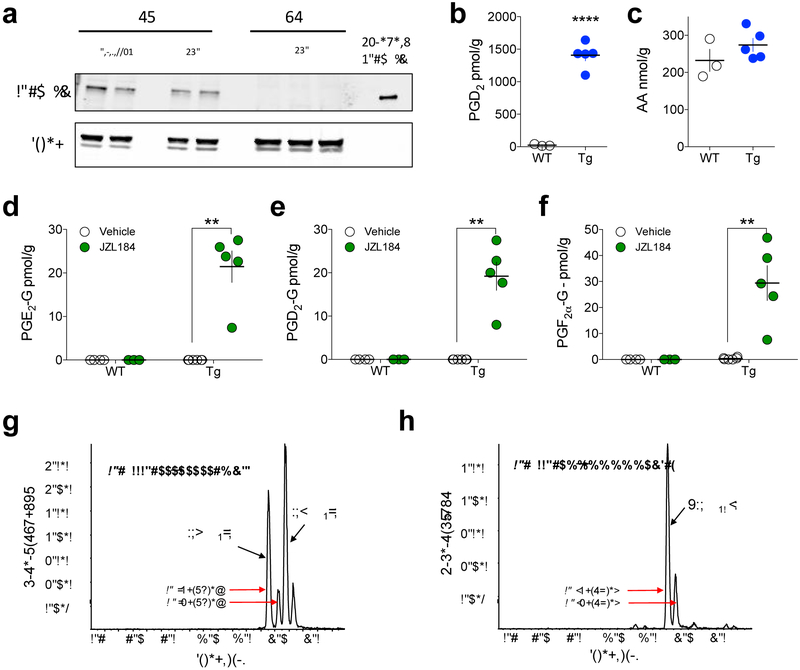

We next considered the possibility that COX-2 levels are too low to generate detectable levels of PG-Gs under basal conditions. To test this hypothesis, we utilized COX-2-Tg mice that overexpress human COX-2 (hCOX-2) in neurons. COX-2-Tg mice showed high levels of hCOX-2 in the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex (PFC) consistent with previous studies27 (Fig. 2a). Levels of PGs, but not free AA, were highly elevated in COX-2-Tg mice (Fig. 2b–c), however we were unable to detect PG-Gs in vehicle-treated COX-2-Tg mice (Fig 2d–f). In contrast, when COX-2-Tg mice were treated with JZL184, a variety of PG-Gs were easily detected (Fig. 2d–f).

Figure 2. Detection of PG-Gs in COX-2-Tg mice after MAGL inhibition.

(a) Validation of COX-2 overexpression in COX-2-Tg mice by western blot. (b-c) COX-2-Tg mice (Tg; n=5, WT; n=3) exhibit high levels of PGD2 but not AA. (d-f) Effects of JZL184 on PG-G levels in WT and COX-2-Tg mice (WT Veh n=4, WT JZL n=3, Tg Veh n=6, Tg JZL n=5). (g-h) Representative chromatograms of endogenous PGE2-G, PGD2-G, and PGF2 α-G in COX-2-Tg mouse brain after JZL184 treatment. ** p<0.01, **** p<0.0001 by t-test (b) or Holm-Sidak test after two-way ANOVA (d-f). Each point (circle) represents a biological replicate (one mouse). Error bars represent S.E.M. Also see Supplementary Fig. 2 (c–d) for representative chromatogram of native PG-Gs using alternate SRM transitions.

Specifically, we detected both sn-1 and sn-2 isomers of PGE2-G, PGD2-G and PGF2α-G in the brains of COX-2-Tg mice treated with JZL184 (40 mg/kg) (Fig. 2d–f and g–h). The sn-2 isomer predominated in all cases (Fig. 2g–h and Fig. S2c–d for confirmatory analysis using alternate SRM transitions). Detection of PG-Gs in COX-2-Tg mice was not due to higher levels of 2-AG after JZL184 treatment relative to WT mice, as 2-AG levels were comparable in WT and COX-2-Tg mice after JZL184 treatment (Fig. S3).

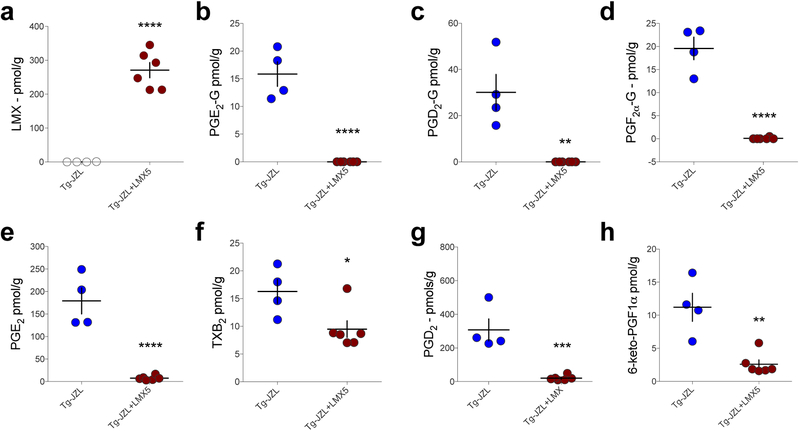

In order to confirm the increase in PG-Gs observed in COX-2-Tg mice after JZL184 treatment was indeed mediated via enzymatic activity of COX-2, we pretreated COX-2-Tg mice with the highly selective COX-2 inhibitor lumiracoxib (LMX; 5 mg/kg). LMX treatment resulted in high drug levels in brain tissue (Fig. 3a) and prevented formation of PG-Gs in COX-2-Tg mice treated with JZL184 (Fig 3b–d). LMX also reduced PG levels in COX-2-Tg mice treated with JZL184 (Fig. 3e–h).

Figure 3. Lumiracoxib (LMX) reduces PG-G levels in COX-2-Tg mice treated with JZL184.

(a) LMX is detected at high levels in brain after i.p. administration (5 mg/kg). (b-d) LMX treatment reduced PG-G levels in JZL184-treated COX-2-Tg mice. (e-h) LMX decreased PG levels in JZL184-treated COX-2-Tg mice (Tg-JZL n=4, Tg-JZL+LMX n=6). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 by unpaired t-test. Each point (circle) represents a biological replicate (one mouse). Error bars represent S.E.M.

We also investigated the effects of two putative substrate-selective COX-2 inhibitors, R-flurbiprofen28 (9 mg/kg) and LM-413129 (10 mg/kg), in combination with JZL184 (40 mg/kg) in COX-2-Tg mice. Both R-flurbiprofen and LM-4131 prevented the formation of PG-Gs, and also reduced levels of all PG species, in COX-2-Tg mice treated with JZL184 (Fig. S4). These data suggest that under the conditions used here, neither compound demonstrated clear substrate-selective profile in vivo. However, we found that ~10% of LM-4131 converted to indomethacin, and also detected S-flurbiprofen in R-flurbiprofen-treated mice (Fig. S5), suggesting pharmacokinetic issues could complicate interpretation of these findings since neither indomethacin nor S-flurbiprofen are substrate-selective.

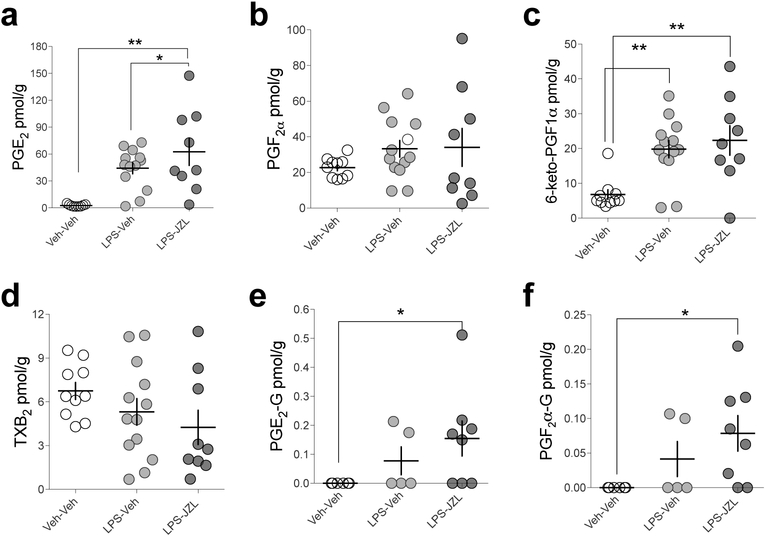

Lastly, the detection of PG-Gs have been reported in other in vivo models of increased COX-2 expression, namely under inflammatory conditions30. To assess the potential COX-2-mediated generation of PG-Gs using an inflammatory model of increased COX-2 expression, we induced neuroinflammation in mice using lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment. We pretreated WT mice with LPS (3 mg/kg, once daily for two days), and JZL184 2h prior to sacrifice. LPS alone and LPS combined with JZL184 increased PGE2 and 6-keto-PGF1α (Fig. 4 a–d) while only LPS combined with JZL184 significantly increased PG-G levels (Fig. 4 e–f), albeit to levels approximately 100-fold lower than seen in COX-2-Tg mice treated with JZL184.

Figure 4. LPS combined with JZL184 pretreatment increases PG and PG-G levels in brain.

(a-d) LPS (3 mg/kg, twice over 48 hours) and LPS+JZL increased PGE2 and 6-keto-PGF1α levels in WT mice (Veh-Veh n=10, LPS-Veh n=13, LPS-JZL n=9). (e-f) LPS+Veh and LPS+JZL did not significantly increase PG-Gs in WT mice (Veh-Veh n=6, LPS-Veh n=5, LPS-JZL n=8). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 by Fisher’s LSD test after one-way ANOVA. Each point represents biological replicate (one mouse). Error bars represent S.E.M.

Here we show that PG-Gs are generated in mouse brain under conditions of increased neuronal COX-2 expression combined with elevated 2-AG levels. Given that our approach to elevating 2-AG utilized inhibition of MAGL, which has also been suggested to hydrolyze PG-Gs26, it is likely that PG-G hydrolysis inhibition facilitated in vivo detection of PG-Gs under these conditions. This is in contrast to prostamides, which are not hydrolyzed by FAAH13, which may account for their previous in vivo detection11, 12. Our data also indicate a requirement for COX-2 enzymatic activity in the generation of PG-Gs, since formation was prevented by the highly selective COX-2 inhibitor LMX. In addition to LMX, we utilized two other compounds that have demonstrated substrate-selective activity (i.e. preferentially inhibiting 2-AG oxygenation by COX-2 over AA) in various assays, R-flurbiprofen28 and LM-413129. Both compounds prevented the formation of most PGs and PG-Gs to a similar degree indicating a lack of substrate-selectivity in vivo. Our data indicate that in vitro substrate-selectivity of these compounds does not translate to in vivo substrate-selectivity across all species of PGs, possibly due to in vivo conversion to non-substrate-selective metabolites. Development of metabolically stable substrate-selective probes is needed to determine whether substrate-selectivity measured in recombinant enzymatic and cellular assays can be measured in vivo and any potential PG species-specific effects of substrate-selective inhibitors.

The function of PG-G signaling is not well understood. At the synaptic level, exogenous PG-Gs can increase inhibitory neurotransmission, possibly via release of intracellular calcium16; these effects are opposite those seen with 2-AG which decreases inhibitory neurotransmission via CB1 receptor activation6, 16. Therefore, it is possible that elevated neuronal COX-2 expression represents a mechanism by which traditional eCB signaling can be “switched” from inhibition to facilitation of presynaptic neurotransmitter release through generation of PG-Gs acting through an as of yet unidentified receptor target. Interestingly, the recent report that PG-Gs activate P2Y6 receptors25, which are known to trigger calcium release in astrocytes31, suggests that PG-Gs may indirectly regulate neurotransmission via astrocyte-neuronal crosstalk. Based on our findings, the conditions under which PG-G signaling occurs would most likely require elevated COX-2 expression and increased levels of 2-AG production, such as those observed after brain injury or inflammation for example32–36. That LPS injection combined with JZL184 treatment led to the detection of PG-Gs (albeit at very low levels) further supports this notion. Future studies should be aimed at determining the precise physiological or pathophysiological conditions under which PG-Gs are generated and the functional significance of these signaling molecules.

Methods

Animals:

Male and female COX-2-Tg mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME; JAX stock #010703) that overexpress COX-2 under the neuron specific Thy-1 promoter or wild-type littermates derived from heterozygous breeding pairs were used as subjects. Mice were 60–90 days of age at time of experimentation. COX-2-Tg and wild-type (WT) progeny were genotyped using PCR analysis of tail genomic DNA. Briefly, tail tissue from tail snips were placed on 95oC heat block in lysis solution for one hour with neutralizing solution applied immediately after. Samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 3 min at 4oC. 2μl of each sample was loaded, with REDTaq DNA polymerase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), autoclaved H2O, and hCOX-2 DNA primers. Following PCR, the results were visualized with gel electrophoresis, using an agarose gel run at 105 V, 3.00 A, for 45 min. Transgenic bands were defined with a top band at 500 kb, and WT mice had top band as well as bottom band (700 kb)27. All WT mice referenced in these experiments are native WT littermates of the COX-2-Tg colony. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Vanderbilt University Office of Animal Welfare.

Drugs:

The MAGL inhibitor JZL184 (40 mg/kg) and R-flurbiprofen (9 mg/kg) were purchased from Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI; Lumiracoxib (5 mg/kg) from Selleck Chemicals, TX, USA; and LM-4131 (10 mg/kg), was synthesized as previously described29; and were administered via intraperitoneal injection (1 ml/kg DMSO) 3 h before sacrifice. LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), was administered via intraperitoneal injection (10 ml/kg; pyrogen-free saline), with two injections of LPS given, 24 h apart. Four hours after the second injection, mice were treated with JZL184 (40 mg/kg). Mice were sacrificed 3 hours after JZL184 or DMSO injection.

Western Blot:

Western blot analysis for COX-2 was performed as previously described using a rabbit-anti hCOX-2 antibody28 (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI).

LC-MS/MS:

Whole mouse brains were frozen on dry ice and stored at -80°C prior to processing and analysis. Brain tissue was prepared for LC-MS/MS analysis as previously described. All LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on a Shimadzu Nexera system in-line with a SCIEX 6500 QTrap as previously described37. The QTrap was equipped with a TurboV Ionspray source and operated in both positive and negative ion mode. SCIEX Analyst software (ver 1.6.2) was used to control the instruments and acquire and process the data. The deuterated internal standards AEA-d4, 2-AG-d5, AA-d8, PGE2-d4, PGD2-d4, PGF2α-d4, 6-keto-PGF2α-d4, TXB2-d4, PGE2-G-d5 were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). Authentic unlabeled standards of these analytes also were purchased from Cayman.

For PG, eCB, and AA analysis, the analytes were chromatographed on an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 reversedphase- column (5.0 × 0.21 cm; 1.7 μm) which was held at 40°C. A gradient elution profile was applied to each sample; %B was increased from 15% (initial conditions) to 99% over 4.0 min and held at 99% for another minute. Then the column was returned to initial conditions for 1.5 min prior to the next injection. The flow rate was 330 μL/min and component A was water with 0.1% formic acid while component B was 2:1 acetonitrile:methanol (v/v) with 0.1% formic acid.

For PG-G analysis, the analytes were chromatographed on a Acquity BEH C18 column (10.0 × 0.21 cm; 1.7 μm) which was held at 42°C. A gradient elution profile was applied to each sample; %B was increased from 6% (initial conditions) to 50% over 8.5 min, then increased to 99% over 0.5 min and held at 99% for another 2.2 min. Finally, the column was returned to initial conditions for 2.5 min prior to the next injection. The flow rate was 300 μL/min and component A was 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH adjusted to approximately 3.3 with glacial acetic acid) while component B was acetonitrile with 5% component A.

All analytes were detected using a SCIEX 6500 QTrap via selected reaction monitoring. Table S1 gives the Q1 and Q3 m/z values, collision energy (CE), declustering potential (DP) and ionization mode for all analytes and their respective internal standards. Analytes were quantitated by stable isotope dilution against their deuterated internal standard. Data was normalized to tissue mass and are presented as either “pmol/g tissue” or “nmol/g tissue”.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by NIH Grants MH100096 (S.P) and S10OD017997. A.M. was supported by T33MH065215.

Abbreviations

- CE

Collision energy

- CID

collision-induced dissociation

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- DP

declustering potential

- eCB

endogenous cannabinoid

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- m/z

mass to charge ratio

- MAGL

monoacylglycerol lipase

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- PG-G

prostaglandin glyceryl esters

- PG-EA

prostaglandin ethanolamide

- SRM

selected reaction monitoring

- Tg

transgenic

- 2-AG

2-arachidonoylglycerol

- AEA

anandamide

- FAAH

fatty-acid amide hydrolase

- AA

arachidonic acid

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LMX

lumiracoxib

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Vanderbilt University owns patent #14/415,977 entitled “Compositions and Methods for Substrate-Selective Inhibition of Endocannabinoid Oxygenation.”

References

- 1.Prospero-Garcia O, Amancio-Belmont O, Becerril Melendez AL, Ruiz-Contreras AE, and Mendez-Diaz M (2016) Endocannabinoids and sleep, Neurosci Biobehav Rev 71, 671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenzel JM, and Cheer JF (2017) Endocannabinoid Regulation of Reward and Reinforcement through Interaction with Dopamine and Endogenous Opioid Signaling, Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(1), 103–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill MN, Campolongo P, Yehuda R, and Patel S (2017) Integrating Endocannabinoid Signaling and Cannabinoids into the Biology and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(1), 80–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cristino L, Becker T, and Di Marzo V (2014) Endocannabinoids and energy homeostasis: an update, Biofactors 40, 389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maccarrone M, Bab I, Biro T, Cabral GA, Dey SK, Di Marzo V, Konje JC, Kunos G, Mechoulam R, Pacher P, Sharkey KA, and Zimmer A (2015) Endocannabinoid signaling at the periphery: 50 years after THC, Trends Pharmacol Sci 36, 277–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katona I, and Freund TF (2012) Multiple functions of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain, Annu Rev Neurosci 35, 529–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marinelli S, Pacioni S, Cannich A, Marsicano G, and Bacci A (2009) Self-modulation of neocortical pyramidal neurons by endocannabinoids, Nat Neurosci 12, 1488–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maroso M, Szabo GG, Kim HK, Alexander A, Bui AD, Lee SH, Lutz B, and Soltesz I (2016) Cannabinoid Control of Learning and Memory through HCN Channels, Neuron 89, 1059–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas EA, Cravatt BF, Danielson PE, Gilula NB, and Sutcliffe JG (1997) Fatty acid amide hydrolase, the degradative enzyme for anandamide and oleamide, has selective distribution in neurons within the rat central nervous system, J Neurosci Res 50, 1047–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozak KR, Crews BC, Morrow JD, Wang LH, Ma YH, Weinander R, Jakobsson PJ, and Marnett LJ (2002) Metabolism of the endocannabinoids, 2-arachidonylglycerol and anandamide, into prostaglandin, thromboxane, and prostacyclin glycerol esters and ethanolamides, J Biol Chem 277, 44877–44885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatta L, Piscitelli F, Giordano C, Boccella S, Lichtman A, Maione S, and Di Marzo V (2012) Discovery of prostamide F2alpha and its role in inflammatory pain and dorsal horn nociceptive neuron hyperexcitability, PLoS One 7, e31111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silvestri C, Martella A, Poloso NJ, Piscitelli F, Capasso R, Izzo A, Woodward DF, and Di Marzo V (2013) Anandamide-derived prostamide F2alpha negatively regulates adipogenesis, J Biol Chem 288, 23307–23321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matias I, Chen J, De Petrocellis L, Bisogno T, Ligresti A, Fezza F, Krauss AH, Shi L, Protzman CE, Li C, Liang Y, Nieves AL, Kedzie KM, Burk RM, Di Marzo V, and Woodward DF (2004) Prostaglandin ethanolamides (prostamides): in vitro pharmacology and metabolism, J Pharmacol Exp Ther 309, 745–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Busquets-Garcia A, Bains J, and Marsicano G (2017) CB1 Receptor Signaling in the Brain: Extracting Specificity from Ubiquity, Neuropsychopharmacology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nomura DK, Morrison BE, Blankman JL, Long JZ, Kinsey SG, Marcondes MC, Ward AM, Hahn YK, Lichtman AH, Conti B, and Cravatt BF (2011) Endocannabinoid hydrolysis generates brain prostaglandins that promote neuroinflammation, Science 334, 809–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sang N, Zhang J, and Chen C (2006) PGE2 glycerol ester, a COX-2 oxidative metabolite of 2-arachidonoyl glycerol, modulates inhibitory synaptic transmission in mouse hippocampal neurons, J Physiol 572, 735–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kozak KR, Rowlinson SW, and Marnett LJ (2000) Oxygenation of the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonylglycerol, to glyceryl prostaglandins by cyclooxygenase-2, J Biol Chem 275, 33744–33749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Straiker A, Wager-Miller J, Hu SS, Blankman JL, Cravatt BF, and Mackie K (2011) COX-2 and fatty acid amide hydrolase can regulate the time course of depolarization-induced suppression of excitation, Br J Pharmacol 164, 1672–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, and Alger BE (2004) Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 potentiates retrograde endocannabinoid effects in hippocampus, Nat Neurosci 7, 697–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chicca A, Gachet MS, Petrucci V, Schuehly W, Charles RP, and Gertsch J (2015) 4’-O-methylhonokiol increases levels of 2-arachidonoyl glycerol in mouse brain via selective inhibition of its COX-2-mediated oxygenation, J Neuroinflammation 12, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rouzer CA, and Marnett LJ (2005) Glycerylprostaglandin synthesis by resident peritoneal macrophages in response to a zymosan stimulus, J Biol Chem 280, 26690–26700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rouzer CA, Tranguch S, Wang H, Zhang H, Dey SK, and Marnett LJ (2006) Zymosan-induced glycerylprostaglandin and prostaglandin synthesis in resident peritoneal macrophages: roles of cyclo-oxygenase-1 and −2, Biochem J 399, 91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alhouayek M, Masquelier J, Cani PD, Lambert DM, and Muccioli GG (2013) Implication of the anti-inflammatory bioactive lipid prostaglandin D2-glycerol ester in the control of macrophage activation and inflammation by ABHD6, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 17558–17563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu SS, Bradshaw HB, Chen JS, Tan B, and Walker JM (2008) Prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester, an endogenous COX-2 metabolite of 2-arachidonoylglycerol, induces hyperalgesia and modulates NFkappaB activity, Br J Pharmacol 153, 1538–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruser A, Zimmermann A, Crews BC, Sliwoski G, Meiler J, Konig GM, Kostenis E, Lede V, Marnett LJ, and Schoneberg T (2017) Prostaglandin E2 glyceryl ester is an endogenous agonist of the nucleotide receptor P2Y6, Sci Rep 7, 2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savinainen JR, Kansanen E, Pantsar T, Navia-Paldanius D, Parkkari T, Lehtonen M, Laitinen T, Nevalainen T, Poso A, Levonen AL, and Laitinen JT (2014) Robust hydrolysis of prostaglandin glycerol esters by human monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL), Mol Pharmacol 86, 522–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vidensky S, Zhang Y, hand T, Goellner J, Shaffer A, Isakson P, and Andreasson K (2003) Neuronal overexpression of COX-2 results in dominant production of PGE2 and altered fever response, Neuromolecular Med 3, 15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duggan KC, Hermanson DJ, Musee J, Prusakiewicz JJ, Scheib JL, Carter BD, Banerjee S, Oates JA, and Marnett LJ (2011) (R)-Profens are substrate-selective inhibitors of endocannabinoid oxygenation by COX-2, Nat Chem Biol 7, 803–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermanson DJ, Hartley ND, Gamble-George J, Brown N, Shonesy BC, Kingsley PJ, Colbran RJ, Reese J, Marnett LJ, and Patel S (2013) Substrate-selective COX-2 inhibition decreases anxiety via endocannabinoid activation, Nat Neurosci 16, 1291–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alhouayek M, and Muccioli GG (2014) COX-2-derived endocannabinoid metabolites as novel inflammatory mediators, Trends Pharmacol Sci 35, 284–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer W, Appelt K, Grohmann M, Franke H, Norenberg W, and Illes P (2009) Increase of intracellular Ca2+ by P2X and P2Y receptor-subtypes in cultured cortical astroglia of the rat, Neuroscience 160, 767–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panikashvili D, Simeonidou C, Ben-Shabat S, Hanus L, Breuer A, Mechoulam R, and Shohami E (2001) An endogenous cannabinoid (2-AG) is neuroprotective after brain injury, Nature 413, 527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartig W, Michalski D, Seeger G, Voigt C, Donat CK, Dulin J, Kacza J, Meixensberger J, Arendt T, and Schuhmann MU (2013) Impact of 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors on the spatiotemporal distribution of inflammatory cells and neuronal COX-2 expression following experimental traumatic brain injury in rats, Brain Res 1498, 69–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunther M, Plantman S, Davidsson J, Angeria M, Mathiesen T, and Risling M (2015) COX-2 regulation and TUNEL-positive cell death differ between genders in the secondary inflammatory response following experimental penetrating focal brain injury in rats, Acta Neurochir (Wien) 157, 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minghetti L (2004) Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in inflammatory and degenerative brain diseases, J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 63, 901–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tzeng SF, Hsiao HY, and Mak OT (2005) Prostaglandins and cyclooxygenases in glial cells during brain inflammation, Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 4, 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bedse G, Hartley ND, Neale E, Gaulden AD, Patrick TA, Kingsley PJ, Uddin MJ, Plath N, Marnett LJ, and Patel S (2017) Functional Redundancy Between Canonical Endocannabinoid Signaling Systems in the Modulation of Anxiety, Biol Psychiatry 82, 488–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.