Abstract

Use of agro-waste for production of value added products is a good alternative for developing low-cost carriers for formulation of Trichoderma-based bio-products. It provides avenues for safe utilization of wastes, while reducing cost and environment pollution load of waste disposal. The present study was undertaken to find suitable agro-waste for economical and higher mass production of Trichoderma lixii TvR1 under solid-state fermentation, optimizing culture conditions using mathematical model and assessing effect of formulated bio-product on growth of Spinach (Spinacia oleracea). Among various agro-wastes screened, sugarcane bagasse was observed to support maximum growth (20.08 × 107 spores/g) of T. lixii TvR1 which was significantly (p ≤ 0.05) higher than the others. The Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was used to optimize culture conditions using optimal point prediction analysis which predicted that maximum spore production of T. lixii TvR1 (19.1245 × 107 spores/g) will be obtained at 30 °C and 68.87% of moisture content after 31 days of incubation. Amendment of formulated bio-product of T. lixii TvR1 in soil at concentration 15% w/w promoted biomass, photosynthetic pigments, and protein content of spinach (significant at p ≤ 0.05). After 6 weeks of sowing the shoot length, root length, and photosynthetic pigments of plants irrigated daily and on alternate days were reported to be increased by 66.97, 185.03, and 82.80%; and 56.56, 71.36, and 74.64%, respectively; over the no amendment.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-018-1360-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Agro-waste, Sub-optimal irrigation, Trichoderma, Optimal point prediction analysis, Photosynthetic pigments

Introduction

Trichoderma is outstanding and versatile genus of fungi that has agricultural as well as industrial importance. It possess ability to promote plant growth and productivity, manage pests and pathogens, alleviate abiotic stresses, biodegrade xenobiotic compounds and produce industrially important metabolites (Mastouri et al. 2010; Blaszczyk et al. 2014; Keswani et al. 2014; Hyder et al. 2017). Earlier species of Trichoderma were generally considered as biocontrol agents that promote plant growth indirectly by inhibiting growth of pathogens, however recently many studies supported their direct role in plant growth. Certain beneficial strains of Trichoderma release several proteinaceous and auxin-like compounds that modify phytohormones leading to plant growth and development on interaction with plants (Garnica-Vergara et al. 2015; Contreras-Cornejo et al. 2016). The vibrant traits of Trichoderma, craft them as a potential candidate for commercial use in agriculture and industries worldwide. For extensive application of Trichoderma based products, large scale production of micropropagules is required. The developmental cost and technological challenges are major hindrance for development of successful product (Singh and Nautiyal 2012; Sachdev and Singh 2016). The cost effective large scale production can be achieved through solid state fermentation. Solid state fermentation (SSF) is a cost effective process, widely used for the mass production of filamentous fungi, their enzymes and/or other metabolites on solid substrates with sufficient moisture but not in free-state (Cavalcante et al. 2008). The raw material used as substrate for biomass production accounts 35–40% of production cost (Eltem et al. 2017). Therefore, utilization of materials that are cheap, easily available and support extensive growth of beneficial fungi is required for cost effective formulation of product.

The factors that influence the mass production of fungi in SSF include temperature, pH, substrate, and moisture content. The variation in environmental factors affects the growth, sporulation, and germination of the propagules. Therefore, substrates used for mass production of fungi should possess ability to retain large number of germinating fungal propagules, without being affected by minor variation in environmental conditions; simultaneously it should be economically viable, stable, and easily reproducible, whenever required, to make process cost-effective. Hence, the environmental conditions must be optimized for SSF to produce micropropagules on large scale.

The present study was aimed on three steps: (1) screening most suitable agro-waste for mass production of Trichoderma lixii TvR1, (2) optimizing culture conditions for maximum mass production of the T. lixii TvR1 through SSF using Box–Behnken design of Response Surface Methodology (RSM), which is a mathematical modeling and a statistical tool providing aid for optimizing conditions in a multivariable system with less number of experiments (Shamshad et al. 2018), and (3) to assess the effect of mass multiplied T. lixii TvR1 on spinach growth under optimal and sub-optimal irrigation regimes.

Materials and methods

Fungal strain and substrate collection

Trichoderma lixii TvR1 accession number MF70730 isolated from root of vetiver roots was used in present study (Sachdev and Singh 2018). Five different agro-wastes, viz. vegetable wastes and spent tea leaves collected from hostel mess, Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar (BBA) University, Lucknow, India; sugarcane bagasse collected from local fruit juice vendors; and cow dung and vermicompost collected from local farms were used for mass multiplication of T. lixii TvR1.

Mass production of Trichoderma on different agro-wastes

The substrates including vegetable wastes and sugarcane bagasse (cut into small pieces < 0.5 cm) were dried under shade. 50 g of each substrate was pre-soaked overnight in sterilized distilled water (SDW) and put into 500 ml conical flask with cotton plug, autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min. The autoclaved substrates were inoculated with 2 ml of spore suspension (1 × 107 spores/ml) of T. lixii TvR1 and incubated at 27 ± 1 °C for 20 days. The experiment was performed in triplicate. The spore density on different substrates was assessed by mixing 1 g of colonized substrate with 9 ml of SDW and agitated at 150 rpm in rotary shaker at room temperature for 1 h. The suspension was filtered through two layers of muslin cloth and spore count was determined by Neubauer’s Haemocytometer as spores/g of substrate.

Optimization of temperature, moisture, and incubation time for mass production of Trichoderma lixii TvR1 using RSM

A factorial experimental design was carried out to optimize mass production at three levels of temperature (25, 30, and 35 °C), moisture (56.50, 64.97, and 68.87%) and incubation time (5, 10, and 15 days) given in Table 1. 20 g of substrate was taken in conical flask, humidified by adding fixed amount of water. The substrates were autoclaved and inoculated with T. lixii TvR1 as mentioned above and incubated at different temperatures in BOD incubator. The spore count was determined at regular interval of time as described above. The growth of T. lixii TvR1 was optimized by Box–Behnken model given by Box and Behnken (1960) and computed using quadratic equation:

Table 1.

Experimental range of three variables at three levels in Box–Behnken design

| Variables | Coded levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| − 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Temperature A (ºC) | 25 | 30 | 35 |

| Moisture B (%) | 56.50 | 64.97 | 68.87 |

| Incubation time C (days) | 5 | 10 | 15 |

where Y predicted response, X determining variable, β0 intercept term, βi linear effect, βii squared effect, βij interaction effect.

Pot experiment

Pot experiment was conducted during April–May, 2015, at environmental field station of BBA University, Lucknow, India, to assess the effect of amendment of T. lixii TvR1, mass multiplied on sugarcane bagasse at different concentrations on growth of spinach under optimal and sub-optimal irrigation regimes, i.e., irrigated daily and on alternate days, respectively. T. lixii TvR1 mass cultured for one week on sugarcane bagasse was mixed with soil at different concentration viz. 5, 10, and 15% w/w. In control setup only soil was used. Further increase in bagasse concentration (beyond 15% w/w) in soil was avoided due to its large volume size. The spinach seeds were procured from local market. The seeds were disinfected with 0.1% HgCl2 solution for 5 min and then rinsed with SDW for thrice before sowing. The experiments were performed in replicate of three and arranged in complete randomized design.

After 6 weeks of sowing, the plants were uprooted carefully and analyzed for various growth and biochemical parameters including root and shoot length, number of leaves, leaf area, fresh and dry weight of root and shoot, total photosynthetic pigments (Lichtenthaler and Wellburn 1983), and total protein content (Lowry et al. 1951).

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were analyzed statistically using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test at significance level of 5% (p ≤ 0.05) using Statistical Analysis software SPSS 16.0 Chicago, SPSS Inc. and Microsoft Office 2007. The results presented as mean ± SD. The mathematical modeling (Response Surface Methodology) was performed using Design Expert software version 9.0.6.

Results and discussion

Mass production of Trichoderma on different agro-waste

The result obtained for mass production of T. lixii TvR1 on different agro-wastes is presented in Table 2. The data show significantly (p ≤ 0.05) higher spore production of T. lixii TvR1 on sugarcane bagasse as compared to other substrates. The sugarcane bagasse constitutes high cellulosic and sucrose content that supports luxurious fungal growth. Degradation of cellulose helps Trichoderma to obtain nutrients effectively (Doni et al. 2014). The sugarcane bagasse also have loose and less compact texture that ease the oxygen diffusion, nutrients absorption and assimilation by the fungal mycelia (Pang et al. 2006). The strain T. lixii TvR1 was found to produce cellulase enzyme (Sachdev and Singh 2018), possessing potential to degrade cellulosic content effectively. The degradation of cellulose fulfills the need of nutrients and presence of sufficient oxygen may be the probable reasons for substantial growth of T. lixii TvR1 on sugarcane bagasse. Several workers have reported various other agro-wastes as suitable substrate for mass production of Trichoderma. Rama et al. (2001) reported sugarcane bagasse with spent tea leaves as best substrate for growth of T. ressei whereas for T. viride and T. koningii, spent tea leaves + wheat bran and for T. harzianum, wheat straw + wheat bran were found as suitable substrates for supporting maximum growth. Analogously, the maximum growth of T. harzianum was reported by Mohiddin et al. (2017) on maize seeds supplement with molasses at 10 °C. The conidial growth of T. harzianum on rice bran was recorded 10.80 × 108 cfu/g, whereas on sugarcane bagasse only 3.73 × 108 cfu/g was documented after 20 days of incubation (Tewari and Bhanu 2004). Similarly, in another study the growth of T. harzianum was recorded higher in coir pith (43 × 1010 cfu/g) as compared to sugarcane bagasse (21 × 1010 cfu/g) after 60 days of incubation (Siddhartha et al. 2017). In contrast to the above reports, the study undertaken by Rajput and Shahzad (2015) demonstrated wheat straw and rice husk as less suitable substrate for growth of T. polysporum. The dissimilarity in growth of different strains of Trichoderma on particular substrate has been well documented in literature. In our study, cow dung was found to support mass production of T. lixii whereas it was reported to be unsuitable for growth of T. polysporum (Rajput and Shahzad 2015). These findings suggest that the mass production of Trichoderma on different substrates is strain-specific owing ability to utilize carbon and nitrogen as a source of nutrition differently.

Table 2.

Spore density of Trichoderma lixii TvR1 on different substrates after 20 days of incubation at 27 ± 1°C

| Organic Substrate | Spore density (1 × 107 spores/g) |

|---|---|

| Spent tea leaves | 3.3 ± 0.50ab |

| Sugarcane bagasse | 20.05 ± 1.56c |

| Cow dung | 2.7 ± 0.35a |

| Vegetable waste | 5.2 ± 1.58b |

| Vermicompost | 3.2 ± 0.283a |

Data are presented as mean of triplicate and values with different letters differ significantly (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05)

Optimization of temperature, moisture and incubation time for mass production of T. lixii TvR1

The influence and interaction of all three factors (temperature, moisture, and time) were investigated in 17 runs using Box–Behnken design and the data are presented in Table 3. The predicted values were calculated using coded values of factors through following equation:

Table 3.

Box–Behnken design determining factors temperature, moisture level, and time interval for spore density of Trichoderma lixii TvR1

| Run | A | B | C | Observed value of spores (1 × 107 spores/g) | Predicted value of spores (1 × 107 spores/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | 56.50 | 10 | 3.735 | 3.835 |

| 2 | 35 | 56.50 | 10 | 2.738 | 2.434 |

| 3 | 25 | 68.87 | 10 | 7.185 | 7.492 |

| 4 | 35 | 68.87 | 10 | 5.856 | 5.759 |

| 5 | 25 | 64.97 | 5 | 0.237 | 0.063 |

| 6 | 35 | 64.97 | 5 | 0 | 0.169 |

| 7 | 25 | 64.97 | 15 | 9.158 | 10.437 |

| 8 | 35 | 64.97 | 15 | 5.452 | 7.074 |

| 9 | 30 | 56.50 | 5 | 1.18 | 1.571 |

| 10 | 30 | 68.87 | 5 | 2.5 | 2.685 |

| 11 | 30 | 56.50 | 15 | 7.138 | 6.955 |

| 12 | 30 | 68.87 | 15 | 13.212 | 12.823 |

| 13 | 30 | 64.97 | 10 | 6.033 | 6.757 |

| 14 | 30 | 64.97 | 10 | 6.033 | 6.757 |

| 15 | 30 | 64.97 | 10 | 6.033 | 6.757 |

| 16 | 30 | 64.97 | 10 | 6.033 | 6.757 |

| 17 | 30 | 64.97 | 10 | 6.033 | 6.757 |

The statistical analysis of obtained data revealed that the model F value was 126.12, suggesting that the model is significant. The value of “Prob > F” was less than 0.05 indicating model terms are significant (Table 4) and the actual values were more or less similar to the predicted values (Supplementary Fig. 1). The value of CV (7.51%) was found to be low, which determined that the experiment was significant. Overall the result obtained showed that model was significant and reliable to determine the variable for maximum spore production.

Table 4.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the experimental results of the quadratic model

| Source | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F value | Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 173.77 | 9 | 19.31 | 126.12 | < 0.0001 (Significant) |

| A-temperature | 4.91 | 1 | 4.91 | 32.09 | 0.0008 |

| B-moisture | 24.37 | 1 | 24.37 | 159.17 | < 0.0001 |

| C-time | 120.46 | 1 | 120.46 | 786.84 | < 0.0001 |

| AB | 0.028 | 1 | 0.028 | 0.18 | 0.6841 |

| AC | 3.01 | 1 | 3.01 | 19.65 | 0.0030 |

| BC | 5.65 | 1 | 5.65 | 36.91 | 0.0005 |

| A 2 | 12.53 | 1 | 12.53 | 81.85 | < 0.0001 |

| B 2 | 1.37 | 1 | 1.37 | 8.96 | 0.0202 |

| C 2 | 1.50 | 1 | 1.50 | 9.77 | 0.0167 |

| Residual | 1.07 | 7 | 0.15 | – | – |

| Lack of fit | 1.07 | 3 | 0.36 | – | – |

| Pure error | 0.000 | 4 | 0.000 | – | – |

| Cor total | 174.85 | 16 | – | – | – |

A, B, C linear model, AC and BC interactive model, A2 quadratic model (significance level p ≤ 0.01%)

CV% = 7.51; R2 = 0.9939; Actual R2 = 0.9860; Predicted R2 = 0.9019

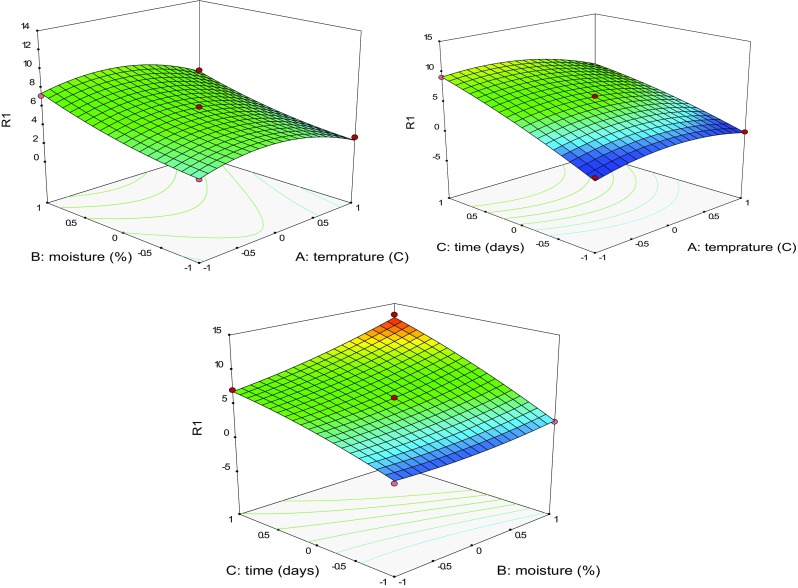

To assess the effect on mass production of Trichoderma (behavior of response) by different culture conditions, three-dimensional response surface contour plots were drawn with respect to simultaneous change in two factors at a time (Fig. 1), which determine the interaction effect and optimum level of factors.

Fig. 1.

Three-dimensional response surface plots showing spore density (1 × 107cfu/g) of Trichoderma lixii TvR1 (R1) under the effect of; A—moisture and temperature; B—time and temperature; C—time and moisture

The maximum spore production of T. lixii TvR1 in all culture conditions studied was found at 30 °C and 68.87% moisture after 15th day incubation (Supplementary Fig. 2) at which spore density was counted 13.21 × 107 spores/g. Cavalcante et al. (2008) have reported 68.41% moisture content favor maximum spore production of Trichoderma spp. on wheat bran and further increase in moisture content decreased the conidial count. This result was supported by the study of Rini and Sulochana (2007), who reported maximum spore density of T. harzianum and T. viride at 60% moisture content on 30th day of incubation on substrates in combination of coir pith and neem cake, and cowdung, neem cake and wheat flour. Moisture content present in SSF affects the physical properties of the substrate. The moisture present cause swelling of the substrates and aid in effective absorption of the nutrients from the substrates that facilitate growth and metabolic activities of fungi (Pang et al. 2006; Cavalcante et al. 2008). Insufficient water content also prevents nutrient accessibility from the substrates by reducing the swelling of substrate which in turn reduce solubilization of nutrients and increase water tension (Pang et al. 2006). Thus, both low as well as high moisture content hinders the growth of fungi in SSF. The optimum temperature that supported maximum growth of T. lixii TvR1 was 30 °C. This result was comparable with the results reported by Shahid et al. (2011) where 25–30 °C was observed as optimum temperature range for fast growth of Trichoderma spp. However, the study undertaken by Mohiddin et al. (2017) 10 °C was found as most favorable temperature, supporting maximum growth of T. harzianum compared to 20 and 30 °C. In our study, after 15 days of incubation, T. lixii TvR1 was still found in growth phase which indicated further increase in incubation time could result in more spore production. The maximum spore production (19.1245 × 107 spores/g) was predicted to be obtained after 31 days of incubation using optimal point prediction analysis under similar condition of temperature and moisture. This finding corroborates with results of Rini and Sulochana (2007), who reported maximum spore density on 30th day after incubation.

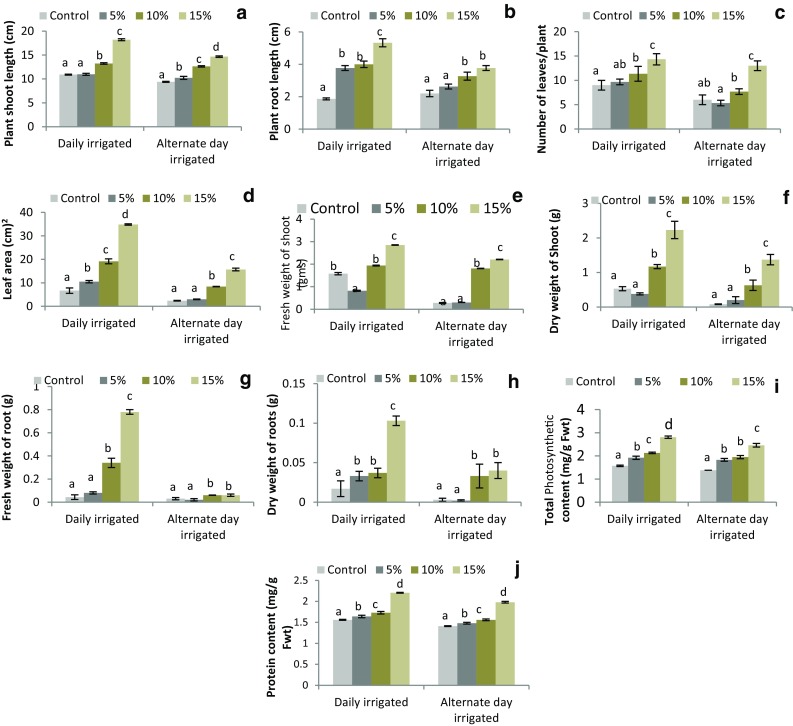

Growth stimulating role of mass multiplied T. lixii TvR1 on spinach

The data presented in Fig. 2a–j show positive relation between spinach growth and increase in concentrations of T. lixii TvR1. The maximum growth and biochemical parameters were reported for spinach plants grown in soil amended with 15% w/w T. lixii TvR1 formulated biofertilizer under both irrigation regimes and were found significantly higher (p ≤ 0.05) than their respective controls. However, plants subjected to alternate day irrigation showed slighlty lower values for growth parameters as compared to plants irrigated daily. Increase in sugarcane bagasse concentration in soil could positively have stimulated the plant growth; however owing to large volume its higher concentration was not taken in present study. This problem can be resolved by increasing concentration of Trichoderma inoculums in sugarcane bagasse. The increased growth of spinach in all treatments as compared to control highlights the positive effect of Trichoderma in plant growth promotion representing Trichoderma as Plant growth promoting fungi (PGPF) effective even under sub-optimal water condition. The increase in growth parameters of maize plant with increase in concentration of Trichoderma has been reported by Akladious and Abbas (2014). This increase may be contributed by the ability of Trichoderma spp. to increase the solubility of insoluble plant nutrients and enhanced uptake by plants and by production of various organic acids that reduce soil pH (Kaya et al. 2009; Akladious and Abbas 2014). Yedidia et al. (2001) reported significant increase in shoot length, plant dry weight and leaf area of cucumber plants colonized by T. asperellum due to enhanced availability of Phosphorus and Iron. Availability of nutrients to plants grown in Trichoderma amended soil may be the reason for increase in plant height, leaf number and area and fresh and dry weight in present work. The Trichoderma spp. are also known to produce phytohormones like auxin and gibberellins that promote lateral root formation and water uptake efficiency from soil (Contreras-Cornejo et al. 2009; Martinez-Medina et al. 2011; Doni et al. 2014). Trichoderma spp. also possess ability to buffer environmental conditions such as drought, pH, flooding, etc. through action of various mechanisms (Doni et al. 2014). Mastouri et al. (2010) and Shukla et al. (2012) observed increased uniformity in seed germination and seedling growth of tomato; and water holding capacity of rice plants, respectively under water deficient condition on inoculation with T. harzianum. Similarly, T. hamatum isolate DIS 219b was found to delay drought response in coco seedling, probably due to the enhanced root growth that improved water status (Bae et al. 2009). These findings are analogous to the findings of present study, demonstrating stimulation of root size of plant may be due to production of phytohormones that strengthens the capacity of plant to anchor more firmly deep into soil and obtain maximum water and nutrients, enhancing physiological processes of plant and resulting in good plant growth and development even under sub-optimal water condition.

Fig. 2.

Growth and Biochemical parameters of Spinach plants grown in soil amended with different concentration of Trichoderma lixii TvR1 mass multiplied on bagasse under different irrigation regimes after 6 weeks of sowing. a Shoot length; b root length; c number of leaves; d leaf area; e fresh shoot weight; f dry shoot weight; g fresh root weight; h dry root weight; i total photosynthetic pigment in mg/g Fwt; and j protein content in mg/g Fwt. Data are presented as mean and values with different letters differ significantly (Tukey’s test, p < 0.05) (n = 3)

Total photosynthetic pigments and protein content were also observed to be increased significantly (p ≤ 0.05) with increase in T. lixii TvR1 and were found comparatively higher in plants irrigated regularly than corresponding alternate day irrigated plants (Fig. 2i). Contreras-Cornejo et al. (2009) and Akladious and Abbas (2014) in their study observed the significant increase in photosynthetic pigment in plants treated with Trichoderma. Shoresh (2010) and Vitti et al. (2016) reported enhanced greenness and photosynthetic activity in maize and tomato plants, respectively, on inoculation with T. harzianum-T22 which may be attributed by reprogramming of plant gene expression. Prolonged photosynthetic activity in rice plants was found to be related with the increased root growth and distribution, attributed by the activity of Trichoderma spp. (Mishra and Salokhe 2011). Increase in protein content in plants may be due to increased uptake of nitrates and other ions. Trichoderma on cellulose degradation release large amount of nitrogen (N) in soil that contributes to high photosynthetic rate (Doni et al. 2014) and protein content (Subramanian et al. 2006) due to increased N uptake by plant. Even Trichoderma spp. are known to enhance nitrogen use efficiency in plants that results in greater yields (Shoresh 2010). These observations suggests degradation of sugarcane bagasse by T. lixii TvR1 may resulted in release of N in soil that positively stimulated photosynthetic and protein content by increasing availability and uptake of N by the spinach plants.

Conclusion

The study concluded that sugarcane bagasse was an efficient agro-waste for mass production of T. lixii TvR1. The sugarcane bagasse was a good source of nutrition that resulted in the significant mass production of T. lixii TvR1 in absence of any additional supplement and retained viable spores. The study also highlighted the fact that the growth of Trichoderma on different agro-wastes could be strain specific. The application of mathematical modeling was a significant approach to optimize the culture conditions with less number of experiments. The results of mathematical modeling indicate its applicability to predict the growth rate of T. lixii TvR1 under different culture conditions. Therefore, this approach could be used to predict impact of controlled environmental conditions on growth rate of fungus and assist in formulation of commercial product. The formulated bio-product effectively promoted the growth of spinach under normal and sub-optimal irrigation condition revealing that the utilization of agro-waste as carrier for formulation of Trichoderma-based bio-product is an economical and safer alternative under prevailing sub-optimal environmental conditions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors gratefully acknowledge University Grant Commission, New Delhi, India for providing UGC Major Research Project; MRP-MAJOR-ENV-2013-11912 and UGC-Senior Research Fellowship grant to Swati Sachdev.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Akladious SA, Abbas SM. Application of Trichoderma harzianum T22 as a biofertilizer potential in Maize growth. J Plant Nutr. 2014;37(1):30–49. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2013.829100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H, Sicher RC, Kim MS, Kim SH, Strem MD, Melnick RL, Bailey BA. The beneficial endophyte Trichoderma hamatum isolate DIS 219b promotes growth and delays the onset of the drought response in Theobroma cacao. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:3279–3295. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Błaszczyk L, Siwulski M, Sobieralski K, Lisiecka J, Jedryczka M. Trichoderma spp.—application and prospects for use in organic farming and industry. J Plant Prot Res. 2014;54(4):309–317. doi: 10.2478/jppr-2014-0047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Box G, Behnken D. Some new three level designs for the study of quantitative variables. Technometrics. 1960;2(4):455–475. doi: 10.1080/00401706.1960.10489912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante RS, Lima HLS, Pinto GAS, Gava CAT, Rodrigues S. Effect of moisture on Trichoderma conidia production on corn and wheat bran by Solid State Fermentation. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2008;1(1):100–104. doi: 10.1007/s11947-007-0034-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Cornejo HA, Macias-Rodriguez L, Cortes-Penagos C, Lopez-Bucio J. Trichoderma virens, a plant beneficial fungus, enhances biomass production and promotes lateral root growth through an auxin-dependent mechanism in arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:1579–1592. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.130369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Cornejo HA, Macias-Rodriguez L, del-Val E, Larsen J. Ecological functions of Trichoderma spp. and their secondary metabolites in the rhizosphere: interactions with plants. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doni F, Isahak A, Zain CRCM, Yusoff WMW. Physiological and growth response of rice plants (Oryza sativa L.) to Trichoderma spp. inoculants. AMB Express. 2014;4:45. doi: 10.1186/s13568-014-0045-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltem R, Sayit S, Sozer S, Sukan FV (2017) Production of Trichoderma citrinoviride micropropagules as a biocontrol agent by means of an economical process. US Patent 9551012

- Garnica-Vergara A, Barrera-Ortiz S, Munoz-Parra E, Raya-Gonzalez J, Mendez-Bravo A, Macias-Rodriguez L, Ruiz-Herrera LF, López-Bucio J. The volatile 6-pentyl-2H-pyran-2-one from Trichoderma atroviride regulates Arabidopsis thaliana root morphogenesis via auxin signaling and ethylene insensitive 2 functioning. N Phytol. 2015;209:1496–1512. doi: 10.1111/nph.13725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyder S, Inam-ul-Haq MD, Bibi S, Malik AH, Ghuffar S, Iqbal S. Novel potential of Trichoderma spp. as biocontrol agent. J Entomol Zool Stud. 2017;5(4):214–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya C, Ashraf M, Sonmez O, Aydemir S, Tuna AL, Cullu MA. The influence of arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization on key growth parameters and fruit yield of pepper plants grown at high salinity. Sci. 2009;121(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Keswani C, Mishra S, Sarma BK, Singh SP, Singh HB. Unraveling the efficient application of secondary metabolites of various Trichoderma. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:533–544. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler HK, Wellburn AR. Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem Soc Trans. 1983;11:591–592. doi: 10.1042/bst0110591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosembrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Medina A, Roldan A, Albacete A, Pascual JA. The interaction with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi or Trichoderma harzianum alters the shoot hormonal profile in melon plants. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastouri F, Björkman T, Harman GE. Seed treatment with Trichoderma harzianum alleviates biotic, abiotic and physiological stresses in germinating seeds and seedlings. Phytopathology. 2010;100(11):1213–1221. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-03-10-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A, Salokhe VM. Rice growth and physiological responses to SRI water management and implications for crop productivity. Paddy Water Environ. 2011;9:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s10333-010-0240-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohiddin FA, Bashir I, Padder SA, Hamid B. Evaluation of different substrates for mass multiplication of Trichoderma species. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2017;6(6):563–569. [Google Scholar]

- Pang PK, Darah I, Poppe L, Szakacs G, Ibrahim CO. Xylanase production by a local isolate, Trichoderma spp. FETL c3-2 via solid state fermentation using agricultural wastes as substrates. Malays J Microbiol. 2006;2(1):7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rajput AQ, Shahzad S. Growth and sporulation of Trichoderma polysporum on organic substrate by addition of carbon and nitrogen sources. Pak J Bot. 2015;47(3):979–986. [Google Scholar]

- Rama SS, Singh HV, Singh P, Kaur J. A comparison of different substrates for the mass production of Trichoderma. Ann Pl Protec Sci. 2001;9(2):248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Rini CR, Sulochana KK. Substrate evaluation for multiplication of Trichoderma spp. J Trop Agric. 2007;45(1–2):58–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev S, Singh RP. Current challenges, constraints and future strategies for development of successful market for biopesticides. Clim Change Environ Sustain. 2016;4(2):129–136. doi: 10.5958/2320-642X.2016.00014.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev S, Singh RP. Isolation, characterisation and screening of native microbial isolates for biocontrol of fungal pathogens of tomato. Clim Change Environ Sustain. 2018;6(1):46–58. doi: 10.5958/2320-642X.2018.00006.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid M, Singh A, Srivastava M, Mishra RP, Biswas SK. Effect of temperature, pH and media for growth and sporulation of Trichoderma longibrachiatum and self life study in carrier based formulations. Ann Pl Protec Sci. 2011;19(1):147–149. [Google Scholar]

- Shamshad A, Vinayak VP, Richa K, Ashwani K, Suresh BNK. Optimization of nutrient stress using C. pyrenoidosa for lipid and biodiesel production in integration with remediation in dairy industry wastewater using response surface methodology. 3 Biotech. 2018;8:326. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1342-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M. Induced systemic resistance and plant responses to fungal biocontrol agents. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2010;48:21–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla N, Awasthi RP, Rawat L, Kumar J. Biochemical and physiological responses of rice (Oryza sativa L.) as influenced by Trichoderma harzianum under drought stress. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2012;54:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddhartha NS, Amara KV, Ramya Mol KA, Saju KA, Harsha KN, Sharanappa P, Kumar KP. Evaluation of substrates for mass production of Trichoderma harzianum and its compatibility with Chlorpyrifos + Cypermethrin. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2017;6(8):3628–3635. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.608.437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PC, Nautiyal CS. A novel method to prepare concentrated conidial biomass formulation of Trichoderma harzianum for seed application. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113(6):1442–1450. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian KS, Santhanakrishnan P, Balasubramanian P. Responses of field grown tomato plants to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal colonization under varying intensities of drought stress. Sci Hortic. 2006;107:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2005.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari L, Bhanu C. Evaluation of agro-industrial waste for conidia based inoculum production of biocontrol agent: Trichoderma harzianum. J Sci Ind Res. 2004;63:807–812. [Google Scholar]

- Vitti A, Pellegrini E, Nali C, Lovelli S, Sofo A, Valerio M, Scopa A, Nuzzaci M. Trichoderma harzianum T-22 induces systemic resistance in tomato infected by Cucumber mosaic virus. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1520. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedidia I, Srivastva AK, Kapulnik Y, Chet I. Effect of Trichoderma harzianum on microelement concentrations and increased growth of cucumber plants. Plant Soil. 2001;235(2):235–242. doi: 10.1023/A:1011990013955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.