Abstract

Capsicum is thought as one of the most diverse and significant genera due to its varied uses in different parts of the world. In this study, we worked with a total of 71 pepper genotypes from different locations of Turkey to investigate the level of their diversity using the peroxidase gene polymorphism (POGP) markers to reveal their population structure. For this purpose, 14 peroxidase primer pairs were used. They produced 139 bands (mean = 9.9 bands/primer), of which ~ 85.6% were polymorphic in the all germplasm collection. Polymorphism information content (PIC) ranged between 0.48 and 0.97 with an average of 0.75. Range and mean values for gene diversity (h) were 0.09–0.22 and 0.17, respectively. Shannon’s information index (I) per POGP marker ranged from 0.18 to 0.35 with a mean of 0.29. Using three clustering methods (unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic means, principal coordinate analysis, and STRUCTURE) revealed a clear separation of all the C. annuum accessions from C. frutescens and C. chinense accessions in our study. Clusters did not establish an association between the accessions and their geographical origin. This is the first study exploring the population structure through the genetic diversity of Turkish peppers from different regions of the country based on the peroxidase gene markers.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-018-1380-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Capsicum, Genetic resources, Peroxidase, Polymorphism

Introduction

Peppers which are the good source of vitamin A and C are grown almost in every part of the world for the variety of the purposes including vegetable, medicinal and ornamental uses (Bosland et al. 2012). Archeological studies indicated that the history of pepper goes to 6000 years ago based on the fossils of food items. They confirm the hypothesis that peppers are one of the first spices used by the human beings in history (Perry et al. 2007). Genus Capsicum belongs to the Solanaceae family. It was originated from the central tropical regions of South America known as Bolivia in the present day (Olmstead et al. 2008). There are twenty-seven identified species in this genus. Five of them were domesticated through prominent events at different locations in America (Nicolai et al. 2013; Olmstead et al. 2008). For the taxonomic studies about this genus, many alternative approaches such as numerical taxonomy, cytogenetics, cross-fertility, geographical, ethnobotanical and biochemical data have been used (Pickersgill 1991; Nicolai et al. 2013). Capsicum annuum, C. frutescens, C. chinense, C. pubescens, and C. baccatum are the most commonly cultivated ones among the identified species of Capsicum genus in the world. It is considered that they were domesticated through five different independent domestication events (Pickersgill 2007). Two regions are known in the history for the domestication of these five species; South America for C. baccatum, C. pubescens, and C. chinense, and Mesoamerica for C. annuum and C. frutescens species (Kumar et al. 2006; Nicolai et al. 2013). Capsicum annuum is the most widely distributed and economically important species of Capsicum in the world. It is a diploid and self-pollinating crop with a chromosome number of 24 (Gyulai et al. 2000). It was shown that C. annuum was domesticated from wild bird pepper known as ‘‘Chiltepin’’ (C. annuum var. glabriusculum) in Mexico (Kraft et al. 2014; Perry et al. 2007). Wild ancestors of C. annuum have red-colored fruits characterized as small, erect, bitter, deciduous and soft-fleshed. These characteristics promote their dispersion through the birds rather than the mammals since birds do not have receptors for capsaicin (Tewksbury and Nabhan 2001). Different lines of fruits with new traits such as smaller, non-pungent or larger fruits have emerged in time as a result of domestication and selection methods (Paran and van der Knaap 2007). Among them, small ones known as hot peppers are mainly used as spices and for condiments purposes. On the other hand, the larger ones known as sweet peppers have gained economical importance across the world due to their higher yield potential (Boslandet al. 2012). It was shown that Turkey is one of the most important areas having great genetic resources of peppers. This valuable source of variation leads to a huge opportunity for the pepper breeding (Bozokalfa et al. 2009). Turkey is not the origin of peppers and still, it is not fully known how Turkey met the peppers for the first time. However, Andrews (1999) stated different speculations about the history of pepper in Turkey. The most accepted hypothesis is that peppers reached into Istanbul (Turkey) as a commercial product during fifteenth and sixteenth centuries through the Portuguese travelling to Asia (Bozokalfa and Eşiyok 2011). Annual production of dry peppers and green peppers in Turkey were reported to be 16,139 and more than 2 million tonnes, respectively (FAOSTAT 2016). Pepper is a favorite vegetable in Turkey. It is consumed in different ways such as in the form of fresh, pickled, grilled, paste, sauce or in cooked dishes (Bozkurt and Erkmen 2005; Yentur et al. 2012).

Studying genetic diversity between different species and also among the individuals within the same species is very crucial. These investigations will produce new perspectives on exploring the candidate parents for the Capsicum breeding. In addition, the information coming from these studies is very helpful to develop novel strategies for the genetic resource conservation not only for the gene banks but also for in situ (González-Pérez et al. 2014). Although there are many strategies and techniques, molecular markers still provide a very effective way of studying the diversity and genetic structure of crop plants (Nadeem et al. 2018). For this purpose, different types of molecular markers have been used by the researchers in their studies involving the wild and the domesticated Capsicum annuum (González-Pérez et al. 2014; Hill et al. 2013; Hulse-Kemp et al. 2016). However, the number of studies about diversity level and population structure of Turkish pepper germplasm is very limited (Aktas et al. 2009; Bozokalfa et al. 2009; Bozokalfa and Eşiyok 2011).

As the members of a multigene family, plant peroxidases exist in the most plants in a large number (Yoshida et al. 2003; Uzun et al. 2014). They are the parts of various important biochemical pathways such as pathogen infection, cell wall lignification as a salt tolerance strategy, auxin degradation, tissue suberization and plant senescence (Hinman and Lang 1965; Espelie et al. 1986; Amaya et al. 1999; Passardi et al. 2005; Gulsen et al. 2010; Ocal et al. 2014; Pinar et al. 2016). It has been shown that the peroxidase gene family possesses highly conserved domains allowing oligonucleotide primers to be designed to amplify DNA sequences coding for peroxidases from many different plants. There are several studies in the literature investigating the peroxidase gene polymorphism (POGP) in a few crops such as buffalo grasses, bermudagrasses, apple, watermelon, Citrus spp., common bean and almond (Gulsen et al. 2007, 2009, 2010; Ocal et al. 2014; Uzun et al. 2014; Nemli et al. 2014; Pinar et al. 2016). Due to critical roles of peroxidases in the evolution of plants, the POGP analyses may increase the understanding of the relationship among Capsicum genotypes from different geographic locations and they may give the new perspectives for pepper breeding.

The main goal of this study was to investigate the level of variation and genetic relatedness among the 71 Turkish pepper accessions. To our best knowledge, this is a very first study to investigate the diversity and population structure of Turkish pepper germplasm using peroxidase gene markers.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

In this study, a total of 71 Capsicum spp., 64 of which are C. annuum, 6 are C. frutescens and 1 is C. chinense were used (Table 1). All the samples were provided by ALATA Horticulture Research Department. They were grown in pots using greenhouse conditions.

Table 1.

Structure code, accession names, accession ID, species, geographical origin and comments/remarks of Capsicum germplasm used in this study

| Structure code | Accession name | Accession ID | Species | Geographical origin | Comments/remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hybrid1 | C. annuum | Turkey | a | |

| 2 | Hybrid2 | C. annuum | Turkey | a | |

| 3 | 283A | C. annuum | Turkey | a | |

| 4 | ChiliPepper1 | 221 | C. annuum | Turkey | Chili pepper |

| 5 | FloridaVR2 | 56 | C. annuum | Florida/USA | Sivri pepper, VR2 X, resistance to Potato Virus Y (PVY) |

| 6 | LamiaType | 1608 | C. annuum | Turkey | Lamia type |

| 7 | Perennial | 67 | C. annuum | a | Perennial, tolerance to CMV and ToMV |

| 8 | KmarasPepper2 | 1779 | C. annuum | Turkey | Kahramanmaras pepper type |

| 9 | BellPepper1 | 467 | C. annuum | Turkey | Bell pepper |

| 10 | ChiliPepper3 | 320 | C. annuum | Turkey | Chili pepper |

| 11 | Kapia2 | 1121A | C. annuum | Turkey | Kapia |

| 12 | Charleston2 | 441 | C. annuum | Turkey | Charleston |

| 13 | BellPepper2 | 405 | C. annuum | Turkey | Bell pepper |

| 14 | Frutescens1 | 1842 | C. frutescens (PI 281418) | University of California, USA | a |

| 15 | Chinense2 | 1840 | C. chinense (PI 159264) | University of Georgia | a |

| 16 | SivriPepper3 | 215 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper, short fruit |

| 17 | KmarasPepper4 | 111 | C. annuum | Turkey | Kahramanmaras pepper type |

| 18 | ChiliPepper4 | 47 | C. annuum | India | Chili pepper, tolerance to high temperature and sensitive to low temperature |

| 19 | Frutescens2 | 1841 | C. frutescens (PI 281421) | University of California, USA | a |

| 20 | HatayPepper | 1676 | C. annuum | Turkey | Hatay pepper |

| 21 | YoloWonder | 66 | C. annuum | USA | Yolo Wonder, tolerance to PVY and TMV |

| 22 | SivriPepper4 | 343 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper |

| 23 | Frutescens4 | 1843 | C. frutescens (PI 281419) | University of California, USA | a |

| 24 | SanliurfaPepper1 | 302 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sanliurfa pepper |

| 25 | Frutescens5 | 1845 | C. frutescens (PI 281422) | University of California, USA | a |

| 26 | ChiliPepper5 | 390 | C. annuum | Turkey | Chili pepper |

| 27 | ChiliPepper6 | 293A | C. annuum | Turkey | Chili pepper |

| 28 | SivriPepper5 | 475A | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper |

| 29 | BellPepper3 | 468 | C. annuum | Turkey | Bell pepper |

| 30 | SivriPepper6 | 164 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper |

| 31 | BellPepper4 | 458 | C. annuum | Turkey | Bell pepper |

| 32 | HungarianPepper1 | 776-7 | C. annuum | Hungary | Hungarian pepper |

| 33 | BellPepper5 | 244 | C. annuum | Turkey | Bell pepper |

| 34 | YoloY | 63 | C. annuum | USA | Yolo Y, tolerance PVY, and TMV |

| 35 | ChiliPepper7 | N50 | C. annuum | Turkey | Chili pepper, tolerance to nematode |

| 36 | SivriPepper7 | 425 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper, high heterosis ability |

| 37 | SivriPepper8 | 24-A | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper |

| 38 | HungarianPepper2 | 765-4-1B | C. annuum | Hungary | Hungarian pepper |

| 39 | HungarianPepper3 | 765-4-2B | C. annuum | Hungary | Hungarian pepper |

| 40 | BellPepper6 | 15-A | C. annuum | Turkey | Bell pepper |

| 41 | SivriPepper10 | 409 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper, high heterosis ability |

| 42 | ChiliPepper8 | 398-A | C. annuum | Turkey | Chili pepper |

| 43 | B7 | B-7 | C. annuum | Turkey | a |

| 44 | SivriPepper11 | N164 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper, tolerance to nematode |

| 45 | KmarasPepper6 | 107 | C. annuum | Turkey | Kahramanmaras pepper type |

| 46 | SivriPepper12 | 32 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper, high heterosis ability |

| 47 | KmarasPepper7 | 1452 | C. annuum | Turkey | Kahramanmaras pepper type |

| 48 | Charleston4 | 333 | C. annuum | Turkey | Charleston, high heterosis ability |

| 49 | SanliurfaPepper2 | İNAN | C. annuum | Turkey | Sanliurfa pepper |

| 50 | Sivripepper14 | 331 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper, high heterosis ability |

| 51 | Kapia3 | K34 | C. annuum | Turkey | Kapia |

| 52 | Kapia4 | K7 | C. annuum | Turkey | Kapia |

| 53 | ChilliPepper9 | 317 | C. annuum | Turkey | Chili pepper |

| 54 | ChiliPepper10 | 35 | C. annuum | Turkey | Chili pepper |

| 55 | ChiliPepper11 | 261 | C. annuum | Turkey | Chili pepper |

| 56 | KmarasPepper8 | KMH-1 | C. annuum | Turkey | Kahramanmaras pepper |

| 57 | Frutescens7 | 287-A | C. frutescens | a | Rosy fruit shape |

| 58 | Kapia5 | K25 | C. annuum | Turkey | Kapia |

| 59 | HungarianPepper8 | 774-4-2B | C. annuum | Hungary | Hungarian pepper, high heterosis ability |

| 60 | Frutescens8 | 287 | C. frutescens | a | Rosy fruit shape |

| 61 | SweetPicle | 1895 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sweet pickle |

| 62 | KmarasPepper9 | 250 | C. annuum | Turkey | Kahramanmaras pepper |

| 63 | BellPepper8 | 1530 | C. annuum | Turkey | Bell pepper |

| 64 | SivriPepper16 | 195 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper |

| 65 | SivriPepper17 | 438 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper, high yield |

| 66 | SivriPepper18 | 407 | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper, very high yield |

| 67 | Aricne | 1882 | C. annuum | USA | a |

| 68 | Kapia6 | 953W | C. annuum | Turkey | Kapia, high yield |

| 69 | SivriPepper19 | 332-D | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper |

| 70 | KmarasPepper10 | 1787 | C. annuum | Turkey | Kahramanmaras pepper |

| 71 | SivriPepper20 | 32-B | C. annuum | Turkey | Sivri pepper, high heterosis ability |

aUnknown location and other characteristics

DNA isolation

Fresh leaves which had been frozen at − 80 °C were lyophilized just before the DNA isolation. Total genomic DNA isolation from lyophilized leaf samples was carried on following the CTAB protocol (Doyle and Doyle 1990) with minor modifications incorporated by Boiteux et al. (1999). Purity and amount of the DNA samples were assessed with NanoDrop (DeNovix DS-11 FX, USA). Finally, DNA samples were diluted to a final concentration of 25 ng/µL for further use in PCR reactions and stored at − 20 °C. All the chemicals and reagents used in this study were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States.

Primer selection and PCR conditions

POGP primers based on 34 rice peroxidase cDNA sequences were used in this study (Gulsen et al. 2007). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Sentromer DNA Technologies, Istinye, Istanbul. Initially, a total of 22 degenerate POGP primer pairs were used on 8 randomly selected peppers’ DNA in PCR reactions. In this screening, 14 POGP primer pairs that yielded intense and polymorphic bands were selected for further analysis in the entire pepper germplasm collection (Table 2). For the PCR reactions, the following substrates were combined in a total volume of 20 µl including 50 ng of template DNA; 2µ l of 1XPCR reaction buffer, 2.5 µl MgCl2, 2 µl dNTP (5 mM), 3 µl (5 mM) each of forward and reverse primer, 0.8 µg/µl bovine serum albumin, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase. Reactions were performed in an automated thermocycler (Applied Biosystems-Veriti Thermal Cycler). The PCR temperature profile used was: 94 °C for 2 min, then 34 cycles consisting of 94 °C for 1 min, 48–57 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min and finally an extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were separated on 2.5% agarose gel in 1 × TBE buffer at 115V for 5 h and visualized using ‘Imager Gel Doc XR+’ system (Bio-Rad, USA). A 100-bp ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as a molecular weight marker.

Table 2.

Peroxidase gene-based primer combinations, fragment size, and estimates for genetic diversity parameters in the Turkish pepper germplasm

| Primer combinations | Fragment size | Amplified bands | % Polymorphism | PIC | h | I | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Polymorphic | ||||||

| POX1F-POX1R | 100–1000 | 10 | 9 | 90 | 0.72 | 0.22 | 0.34 |

| POX5F-POX5R | 200–900 | 10 | 9 | 90 | 0.77 | 0.12 | 0.22 |

| POX6F-POX6R | 100–1000 | 12 | 11 | 91.7 | 0.48 | 0.18 | 0.31 |

| POX9F-POX9R | 80–1600 | 13 | 12 | 92.3 | 0.68 | 0.21 | 0.34 |

| POX10Fa-POX10Ra | 100–1600 | 7 | 6 | 85.7 | 0.86 | 0.09 | 0.18 |

| POX10Fa-POX10Rb | 200–1000 | 8 | 6 | 75 | 0.97 | 0.17 | 0.29 |

| POX10Fa-POX10Rc | 80–1200 | 9 | 7 | 77.8 | 0.77 | 0.21 | 0.35 |

| POX10Fa-POX10Rd | 100–1400 | 14 | 12 | 85.7 | 0.78 | 0.16 | 0.29 |

| POX10 Fb-POX10Rc | 100–1400 | 7 | 6 | 85.7 | 0.89 | 0.15 | 0.27 |

| POX10Fb-POX10Re | 200–800 | 11 | 11 | 100 | 0.60 | 0.17 | 0.29 |

| POX10Fc-POX10Re | 200–1600 | 11 | 9 | 81.8 | 0.77 | 0.19 | 0.31 |

| POX10Fd-POX10Re | 80–900 | 7 | 6 | 85.7 | 0.67 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| POX11F-POX11R | 80–500 | 11 | 10 | 90.9 | 0.83 | 0.21 | 0.34 |

| POX12Fa-POX12Ra | 80–900 | 9 | 6 | 66.7 | 0.69 | 0.09 | 0.19 |

| Total | 139 | 120 | |||||

| Average | 9.9 | 8.6 | 85.6 | 0.75 | 0.17 | 0.29 | |

PIC polymorphic information content, h gene diversity, I Shannon's information index

Data analysis

For the data analysis, only reproducible and legible bands were used. Gel images were evaluated and a data matrix was developed using ‘1’ for the existence and ‘0’ for the absence of POGP bands. Analysis of gene diversity and Shannon information index within and among in 71 peppers’ genome were carried out using POPGENE version 1.32 software (Yeh et al. 2000). The average Polymorphism Information Content (PIC) for dominant markers was calculated according to De Riek et al. (2001) by the following formula:

where f is the frequency of the marker in the data set. PIC for dominant markers is a maximum of 0.5 for f = 0.5.

Genetic diversity among 71 peppers was constructed using the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic average (UPGMA) based on the Jaccard’s similarity coefficient (Jaccard 1908). The distribution of populations was analyzed with principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) using PAST3. Analysis of the population structure among 71 pepper genotypes was carried out using a model-based Bayesian clustering model executed with the software STRUCTURE. The number of subgroups (K) in the population was determined by calculating the ad hoc statistics ΔK, based on the rate of change in the ln probability of data between successive K values (Evanno et al. 2005).

Results and discussion

PCR reactions of 71 pepper accessions with 14 polymorphic POGP primer pairs produced a total of 139 expressive bands with an average of 9.9 fragments per primer (Table 2). Among the bands, 85.6% were found polymorphic. 8.6% was the average number of polymorphic fragments per primer and band size ranged from 80 to 1600 bp (Table 2). POX10Fa-POX10Rd primer combination produced the maximum (Supplementary Figure 1), on the other hand, POX10Fa-POX10Ra (Supplementary Fig. 2), POX10Fb-POX10Rc, and POX10Fd-POX10Re primer combinations gave the minimum numbers of bands which were 14 and 7, respectively. A maximum number of polymorphic bands (12) were resulted with the POX9 and POX10Fa-POX10Rd, while the minimum number of polymorphic bands (6) resulted with the POX10Fa-POX10Ra, POX10Fa-POX10Rb, POX10Fb-POX10Rc, POX10Fd-POX10Re and POX12Fa-POX12Ra primer pairs. All of these selected 14 primer pairs resulted in a higher level of polymorphism with an average of 85.6% in Turkish pepper germplasms. The number of polymorphic bands obtained in this study is higher than those previously performed by Ibarra-Torres et al. (2015) and Aktas et al. (2009). Ibarra-Torres et al. (2015) found 24 and 36 polymorphic SSRs and ISSRs for addressing inter- and intraspecific diversity in C. pubescens and C. annuum, respectively. Aktas et al. (2009) revealed 56 polymorphic AFLPs for assessing the genetic diversity in Turkish C. annuum accessions. On the other hand, Krishnamurthy et al. (2015) reported 389 polymorphic and 414 total bands using AFLPs in a collection of 59 C. annuum and C. baccatum accessions which is a higher level of polymorphism as compared to the present study. Nonetheless, it must be noted that both studies, using AFLP (Krishnamurthy et al. 2015) and POGP markers (the present study), revealed higher polymorphic bands compared to other studies. Thus, it may be concluded that POGP represents an excellent cost-effective marker option for detecting genetic variations in Capsicum.

Average value of polymorphism information contents (PIC) was 0.75. POX10Fa-POX10Rb and POX6 primer pairs gave the maximum and the minimum PIC values which were 0.97 and 0.48, respectively. Both range and average PIC values were found higher than those obtained by the Naegele et al. (2016) (PIC = 0.40). They used SSR markers in a C. annuum collection from 9 countries in their study. In addition, the average PIC value found in this study is higher than the mean PIC of 0.69 obtained in the study using a Capsicum collection conducted by Rai et al. (2013).

Range and mean values for gene diversity (h) were 0.09–0.22 and 0.17, respectively. Allelic diversity and genomic distribution of markers are considered as universal criteria for the identification of cultivars. According to Werner et al. (2004), candidate markers should have allele frequency higher than 0.1. We obtained a higher level of Shannon’s information index for all primers. Average Shannon’s information index was 0.29. POX10Fa-POX10Rc and POX10Fa-POX10Ra were two primer pairs resulting in the maximum and minimum Shannon’s information index, 0.35 and 0.18, respectively (Table 2). Our results were found to be parallel with the results of Aktas et al. (2009) investigating on Turkish pepper. However, range and average Shannon’s information index were found much lower than the results obtained by Jung et al. (2010). They reported higher average (I = 0.49) and range (I = 0.035–0.69) of Shannon’s information index using SNP markers in Capsicum genus.

Pair-wise genetic similarity (GS) values (Jaccard) among 71 peppers were also used to evaluate the level of diversity more clearly. It revealed that SivriPepper14 and Charleston4 were the most similar accessions with the value of GS, 0.95. It was followed by BellPepper8-BellPepper2 and KmarasPepper10-KmarasPepper2 with the value of GS, 0.93. They were developed using a common progenitor. On the other hand, the genetically most distant accessions were frutescens7–frutescens1, frutescens8–frutescens1 and frutescens8–frutescens5 with the value of GS, 0.11. Overall, the average GS value in the entire pepper collection was 0.63. These genetically distinct variants within C. annuum and C. frutescens can be used for developing populations for traits of interest, as well as for generating and selecting new phenotypic variants for breeding purposes.

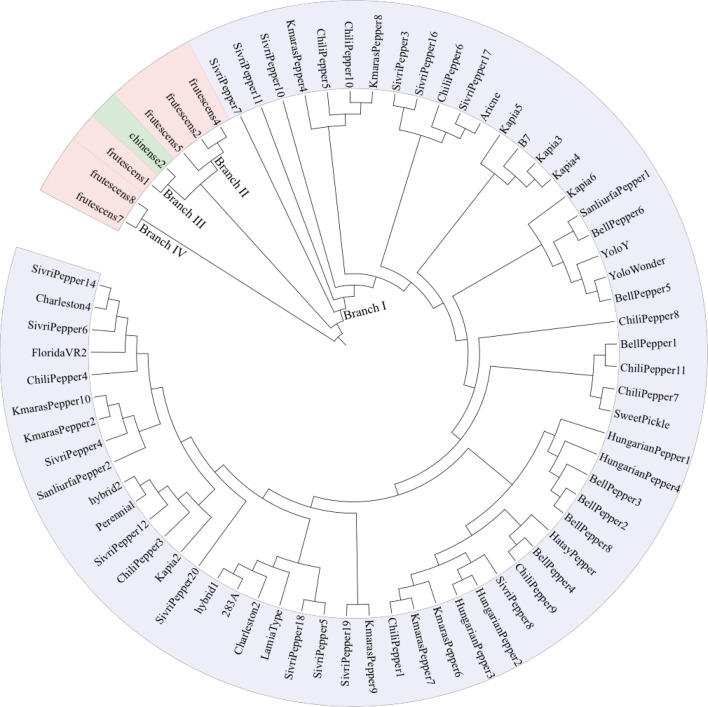

In UPGMA cluster analysis, the genotypes were grouped into four major clusters defined as branches I–IV in Fig. 1. The first cluster (I) involved the largest number of the accessions which belong to the C. annuum species (64 accessions, representing 90% of the pepper collection). Within this group, no clear association was found between clustering and geographical origin or fruit characteristics of the individuals. Branch III included both C. chinense and C. frutescens. The content of this branch supports the hypothesis that C. chinense was developed from C. frutescens (Djian-Caporilano et al. 2007). On the other hand, Branch II and branch IV contained accessions from C. frutescens only.

Fig. 1.

UPGMA-based clustering of 71 Turkish pepper accessions. Four groups originated in branches I–IV

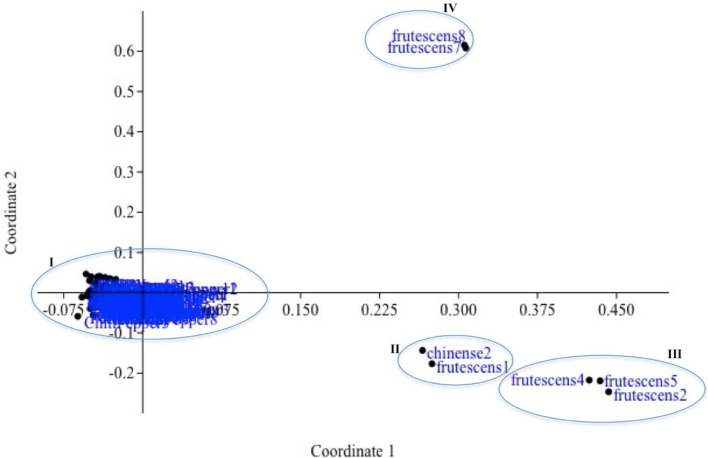

The principal coordinate analysis (PcoA) was applied to obtain more detailed insights into the genetic relationship among the 71 Turkish pepper germplasms. PCoA verified the results of UPGMA which also clustered the genotypes into four groups (Fig. 2). Similar to the UPGMA clustering pattern, PCoA showed that all the individuals belonging to C. annuum grouped into the same branch and most of C. frutescens and C. chinense clustered together. However, different from UPGMA results, it was found that some individuals of C. frutescens (frutescen8–frutescens7) scattered away from their axis. The rosy fruit shape of these frutescens may contribute to this difference. Population substructure was found in the Turkish pepper germplasm, with two major genetic pools identified (K = 2); a C. frutescens group (cluster I), a ‘C. frutescens + C. chinense’ group (cluster II) and a C. annuum group (cluster III) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Genetic clustering of 71 Capsicum accessions based on the principal component analysis (PCoA) of 120 POGP marker data

Fig. 3.

Population structure estimated by Bayesian clustering. Each individual is represented by a vertical line. The numbers on the x-axis represent the Capsicum accessions indicated in Table 1

Our results using all three clustering methods (UPGMA, PCoA, and Structure) presented a clear separation of all the C. annuum accessions from C. frutescens and C. chinense accessions. They are in close agreement with those reported by González-Pérez et al. (2014) who found the clear genetic separation among accessions belonging to C. annuum, C. frutescens, and C. chinense.

In conclusion, this study characterized the genetic diversity and population structure in the Turkish pepper germplasm using POGP markers for the first time. It was shown that they separated the C. annuum accessions from C. frutescens and C. chinense accessions clearly. They were used successfully as highly polymorphic and cost-efficient markers for addressing genetic-related questions in Capsicum in our experiments. In recent years, the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has facilitated the development of new genetic markers such as GBS-SNPs and is still increasingly being deployed to guide researchers in developing the resolution and informativeness of the analysis. It is expected that the results from this study will have a positive impact on pepper breeding and genetic research in Turkey and elsewhere.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Project Units of Van Yuzuncu Yil University (Project number: FYL-2016-5521). We would like to express our gratitude to ALATA Horticultural Research Institute for providing seed samples.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed to the work, and they have agreed to submit the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no financial/commercial conflict of interest.

References

- Aktas H, Abak K, Sensoy S. Genetic diversity in some Turkish pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes revealed by AFLP analyses. Afr J Biotech. 2009;8:4378–4386. [Google Scholar]

- Amaya I, Botella MA, de la Calle M, Medina MI, Heredia A, Bressan RA, Hasegawa PM, Quesada MA, Valpaesta V. Improved germination under osmotic stress of tobacco plants over expressing a cell wall peroxidase. FEBS Lett. 1999;457:80–84. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J. Pepper trail: history and recipes from around the world. Denton, Texas, USA: University of North Texas Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Boiteux LS, Fonseca MEN, Simon PW. Effects of plant tissue and DNA purification methods on randomly amplified polymorphic DNA-based genetic fingerprinting analysis in carrot. J Am Soc Hort Sci. 1999;124:32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bosland PW, Votava EJ, Votava EM. Peppers: vegetable and spice capsicums. Crops Prod Sci Hortic. 2012;12:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt H, Erkmen O. Effects of salt, starter culture and production techniques on the quality of hot pepper paste. J Food Eng. 2005;69(4):473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.08.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bozokalfa MK, Eşiyok D. Evaluation of morphological and agronomical characterization of Turkish pepper accessions. Int J Veg Sci. 2011;17(2):115–135. doi: 10.1080/19315260.2010.516329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bozokalfa MK, Esiyok D, Turhan K. Patterns of phenotypic variation in a germplasm collection of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) from Turkey. Span J Agric Res. 2009;7(1):83–95. doi: 10.5424/sjar/2009071-401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Riek J, Calsyn E, Everaert I, Van Bockstaele E, De Loose M. AFLP based alternatives for the assessment of distinctness, uniformity and stability of sugar beet varieties. Theor Appl Genet. 2001;103:1254–1265. doi: 10.1007/s001220100710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Djian-Caporilano C, Lefebvre V, Sage-Daubeze AM, Palloix A. Capsicum. In: Singh RJ, editor. Genetic resources, chromosome engineering, and crop improvement: vegetable crops. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 185–243. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus. 1990;12:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Espelie KE, Franceschi VR, Kolattukudy PE. Immunocyto- chemical localization and time course of appearance of an anionic peroxidase associated with suberization in wound- healing potato tuber tissue. Plant Physiol. 1986;81:487–492. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.2.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT (2016) http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC

- González-Pérez S, Garcés-Claver A, Mallor C, de Miera LE, Fayos O, Pomar F, Merino F, Silvar C. New insights into Capsicum spp relatedness and the diversification process of Capsicum annuum in Spain. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e116276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulsen O, Shearman RC, Heng-Moss TM, Mutlu N, Lee DJ, Sarath G. Peroxidase gene polymorphism in buffalograss and other grasses. Crop Sci. 2007;47:767–772. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2006.07.0496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gulsen O, Sever-Mutlu S, Mutlu N, Tuna M, Karaguzel O, Shearman RC, Riordan TP, Heng-Moss TM. Polyploidy creates higher diversity among Cynodon accessions as assessed by molecular markers. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;118:1309–1319. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-0982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulsen O, Kaymak S, Ozongun S, Uzun A. Genetic analysis of Turkish apple germplasm using peroxidase gene-based markers. Sci Hortic. 2010;125:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2010.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gyulai G, Gémesné JA, Sági ZS, Venczel G, Pintér P, Kristóf Z, Törjék O, Heszky L, Bottka S, Kiss J, Zatykó L. Doubled haploid development and PCR-analysis of F1 hybrid derived DH-R2 paprika (Capsicum annuum L.) lines. J Plant Physiol. 2000;156(2):168–174. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(00)80302-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TA, Ashrafi H, Reyes-Chin-Wo S, Yao J, Stoffel K, Truco MJ, Kozik A, Michelmore RW, Van Deynze A. Characterization of Capsicum annuum genetic diversity and population structure based on parallel polymorphism discovery with a 30K unigene Pepper GeneChip. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinman RL, Lang J. Peroxidase catalyzed oxidation of indole- 3-acetic acid. Biochemistry. 1965;4:144–158. doi: 10.1021/bi00877a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulse-Kemp AM, Ashrafi H, Plieske J, Lemm J, Stoffel K, Hill T, Luerssen H, Pethiyagoda CL, Lawley CT, Ganal MW, Van Deynze A. A HapMap leads to a Capsicum annuum SNP infinium array: a new tool for pepper breeding. Hortic Res. 2016;3:16036. doi: 10.1038/hortres.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra-Torres P, Valadez-Moctezuma E, Pérez-Grajales M, Rodríguez-Campos J, Jaramillo-Flores ME. Inter-and intraspecific differentiation of Capsicum annuum and Capsicum pubescens using ISSR and SSR markers. Sci Hortic. 2015;181(2):137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.10.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard P. Nouvelles recherchessur la distribution florale. Bull Soc Vaud Sci Nat. 1908;44:223–270. [Google Scholar]

- Jung JK, Park SW, Liu WY, Kang BC. Discovery of single nucleotide polymorphism in Capsicum and SNP markers for cultivar identification. Euphytica. 2010;175(1):91–107. doi: 10.1007/s10681-010-0191-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft KH, Brown CH, Nabhan GP, Luedeling E, Ruiz JD, d’Eeckenbrugge GC, Hijmans RJ, Gepts P. Multiple lines of evidence for the origin of domesticated chili pepper, Capsicum annuum, in Mexico. PNAS. 2014;111(17):6165–6170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308933111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy SL, Prashanth Y, Rao AM, Reddy KM, Ramachandra R. Assessment of AFLP marker based genetic diversity in chilli (Capsicum annuum. L. & C. baccatum L.) Indian J Biotechnol. 2015;14(1):49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Kumar R, Singh J. Cayenne/American pepper (Capsicum species) In: Peter KV, editor. Handbook of herbs and spices. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing; 2006. pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem MA, Nawaz MA, Shahid MQ, Doğan Y, Comertpay G, Yıldız M, Hatipoğlu R, Ahmad F, Alsaleh A, Labhane N, Özkan H. DNA molecular markers in plant breeding: current status and recent advancements in genomic selection and genome editing. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2018;32(2):261–285. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2017.1400401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naegele RP, Mitchell J, Hausbeck MK. Genetic Diversity, Population Structure, and Heritability of Fruit Traits in Capsicum annuum. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0156969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemli S, Kaya HB, Tanyolac B. Genetic assessment of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) accessions by peroxidase gene-based markers. J Sci Food Agric. 2014;94(8):1672–1680. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolai M, Cantet M, Lefebvre V, Sage-Palloix AM, Palloix A. Genotyping a large collection of pepper (Capsicum spp.) with SSR loci brings new evidence for the wild origin of cultivated C. annuum and the structuring of genetic diversity by human selection of cultivar types. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2013;60(8):2375–2390. doi: 10.1007/s10722-013-0006-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ocal N, Akbulut M, Gulsen O, Yetisir H, Solmaz I, Sari N. Genetic diversity, population structure and linkage disequilibrium among watermelons based on peroxidase gene markers. Sci Hortic. 2014;176:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead RG, Bohs L, Migid HA, Santiago-Valentin E, Garcia VF, Collier SM. A molecular phylogeny of the Solanaceae. Taxon. 2008;57(4):1159–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Paran I, van der Knaap E. Genetic and molecular regulation of fruit and plant domestication traits in tomato and pepper. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(14):3841–3852. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passardi F, Cosio C, Penel C, Dunand C. Peroxidases have more functions than a Swiss army knife. Plant Cell Rep. 2005;24:255–265. doi: 10.1007/s00299-005-0972-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry L, Dickau R, Zarrillo S, Holst I, Pearsall DM, Piperno DR, Berman MJ, Cooke RG, Rademaker K, Ranere AJ, Raymond JS, et al. Starch fossils and the domestication and dispersal of chili peppers (Capsicum spp. L.) in the Americas. Science. 2007;315(5814):986–988. doi: 10.1126/science.1136914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickersgill B. Cytogenetics and evolution of Capsicum. In: Part L, editor. Chromosome engineering in plants: genetics, breeding, evolution. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1991. pp. 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Pickersgill B. Domestication of plants in the Americas: insights from Mendelian and molecular genetics. Ann Bot. 2007;100(5):925–940. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinar H, Unlu M, Ercisli S, Uzun A, Bircan M. Genetic analysis of selected almond genotypes and cultivars grown in Turkey using peroxidase-gene-based markers. J For Res. 2016;27(4):747–754. doi: 10.1007/s11676-016-0213-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rai VP, Kumar R, Kumar S, Rai A, Kumar S, Singh M, Singh SP, Rai AB, Paliwal R. Genetic diversity in Capsicum germplasm based on microsatellite and random amplified microsatellite polymorphism markers. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2013;19(4):575–586. doi: 10.1007/s12298-013-0185-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewksbury JJ, Nabhan GP. Seed dispersal: directed deterrence by capsaicin in chillies. Nature. 2001;412:403–404. doi: 10.1038/35086653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzun A, Gulsen O, Seday U, Yesiloglu T, Aka Kacar Y. Peroxidase gene-based estimation of genetic relationships and population structure among Citrus spp. and their relatives. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2014;61:1307–1318. doi: 10.1007/s10722-014-0112-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werner FA, Durstewitz G, Habermann FA, Thaller G, Krämer W, Kollers S, Buitkamp J, Georges M, Brem G, Mosner J, Fries R. Detection and characterization of SNPs useful for identity control and parentage testing in major European dairy breeds. Anim Genet. 2004;35(1):44–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.2003.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh FC, Yang R, Boyle TJ, Ye Z, et al. Pop Gene 32, Microsoft Windows-based Freeware for population genetic analysis. Version 1.32. Edmonton: Mol Biol Biotechnol Centre University of Alberta; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yentur G, Onurdag FK, Er B, Demirhan B. Investigation of aflatoxin B1 levels in red pepper and products consumed in Ankara. Turk J Pharm Sci. 2012;9(3):293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Kaothien P, Matsui T, Kawaoka A, Shinmyo A. Molecular biology and application of plant peroxidase genes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;60:665–670. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.