Abstract

Background

Mutations in GJB2 gene are a major causes of deafness and their spectrum and prevalence are specific for various populations. The well-known mutation c.35delG is more frequent in populations of Caucasian origin. Data on the c.35delG prevalence in Russia are mainly restricted to the European part of this country. We aimed to estimate the carrier frequency of c.35delG in Western Siberia and thereby update current data on the c.35delG prevalence in Russia. According to a generally accepted hypothesis, c.35delG originated from a common ancestor in the Middle East or the Mediterranean ~ 10,000–14,000 years ago and spread throughout Europe with Neolithic migrations. To test the c.35delG common origin hypothesis, we have reconstructed haplotypes bearing c.35delG and evaluated the approximate age of c.35delG in Siberia.

Methods

The carrier frequency of c.35delG was estimated in 122 unrelated hearing individuals living in Western Siberia. For reconstruction of haplotypes bearing c.35delG, polymorphic D13S141, D13S175, D13S1853 flanking the GJB2 gene, and intragenic rs3751385 were genotyped in deaf patients homozygous for c.35delG (n = 24) and in unrelated healthy individuals negative for c.35delG (n = 67) living in Siberia.

Results

We present updated carrier rates for c.35delG in Russia complemented by new data on c.35delG carrier frequency in Russians living in Western Siberia (4.1%). Two common D13S141-c.35delG-D13S175-D13S1853 haplotypes, 126-c.35delG-105-202 and 124-c.35delG-105-202, were reconstructed in the c.35delG homozygotes from Siberia. Moreover, identical allelic composition of the two most frequent c.35delG haplotypes restricted by D13S141 and D13S175 was established in geographically remote regions: Siberia and Volga-Ural region (Russia) and Belarus (Eastern Europe).

Conclusions

Distribution of the c.35delG carrier frequency in Russia is characterized by pronounced ethno-geographic specificity with a downward trend from west to east. Comparative analysis of the c.35delG haplotypes supports a common origin of c.35delG in some regions of Russia (Volga-Ural region and Siberia) and in Eastern Europe (Belarus). A rough estimation of the c.35delG age in Siberia (about 4800 to 8100 years ago) probably reflects the early formation stages of the modern European population (including the European part of the contemporary territory of Russia) since the settlement of Siberia by Russians started only at the end of sixteenth century.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12881-018-0650-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Deafness; GJB2, c.35delG; Haplotypes; Siberia

Background

Pathogenic variants in the GJB2 gene (MIM 121011, chromosome 13q11q12) are the most common causes of autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing loss in various populations. Over 300 pathogenic variations in GJB2 have been reported in the Human Gene Mutation Database [1]. Many of them have high ethno-geographic specificity in prevalence [2], which for certain ethnic groups is being attributed to a founder effect [3–11].

The recessive pathogenic GJB2 variant c.35delG (p.Gly12Valfs*2) (NM_004004.5) is known to be prevalent in deaf patients of Caucasian origin [2, 12, 13]. Previous studies have revealed the c.35delG carrier frequency to be around 1 in 50 overall in Europe [12], reaching 1 in 31 in Southern Europe [14]. In meta-analysis of the data published up to 2008, mean carrier frequencies of c.35delG were found to be 1.89, 1.52, 0.64, 1, and 0.64% for European, American, Asian, Oceanic, and African populations, respectively [13]. The c.35delG is a deletion of one guanine (G) from a string of six (GGGGGG) in the GJB2 coding sequence resulting in a frameshift and termination of the Cx26 protein sequence at amino acid 13 (p.Gly12Valfs*2). The occurrence of c.35delG as a possible “hot spot” caused by DNA polymerase “slippage” was previously assumed to be an explanation of the high prevalence of this pathogenic variant in the GJB2 gene [5, 15, 16]. Nevertheless, convincing evidence emerged that the founder effect plays an important role in the prevalence and accumulation of c.35delG in populations of Caucasian origin since lower rates or absence of c.35delG are observed in other populations. According to a generally accepted hypothesis, c.35delG originated from a common ancestor in the Middle East or the Mediterranean approximately 10,000–14,000 years ago and spread throughout Europe with Neolithic migrations. Specific c.35delG prevalence and discovery of common STR- and SNP-haplotypes bearing the c.35delG mutation in Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, North-European populations, and in individuals of European origin in the USA support this hypothesis [14, 17–27]. Relevant data were also obtained for populations of the Volga-Ural region of Russia [28] and Belarus [29].

The c.35delG predominance in deaf patients was reported in several studies conducted in the European part of Russia [30–38]. In the ethnically heterogeneous population of Siberia, epidemiological and molecular genetic studies of hereditary deafness are currently limited to regions of the Altai Republic, the Tuva Republic (Southern Siberia), and the Sakha Republic (Yakutia, Eastern Siberia) [39–41]. The presence of c.35delG in a homozygous or compound-heterozygous state was the main cause of hereditary hearing loss in deaf Russian patients living in these regions in contrast to deaf patients belonging to Siberian indigenous peoples (Altaians, Tuvinians, Yakuts) who were negative for the c.35delG mutation [39–41].

This study presents an updated summary of published data on the c.35delG (p.Gly12Valfs*2) prevalence in Russia complemented by our original data on the c.35delG carrier frequency in Western Siberia. To test the c.35delG common origin hypothesis, we genotyped polymorphic markers flanking the GJB2 gene and reconstructed haplotypes bearing c.35delG in deaf patients from Siberia homozygous for c.35delG.

Methods

Subjects

Twenty-four unrelated patients (mostly Russians) with congenital or early onset profound hearing loss living in several Siberian regions (Altai, Tuva, Yakutia) were previously found to be homozygous for c.35delG [39–41]. The carrier frequency of c.35delG was estimated in 122 unrelated normal hearing individuals (mostly Russians) from the Novosibirsk region (Western Siberia). Genotyping of three polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) markers D13S141, D13S175, D13S1853 and an intragenic SNP (rs3751385) was performed in 24 unrelated deaf patients homozygous for c.35delG and in 67 unrelated healthy individuals from the Novosibirsk region (Western Siberia) who were negative for c.35delG.

C.35delG screening and analysis of genetic markers

All primers and genotyping methods are summarized in Table 1. The c.35delG screening was performed according to [42]. Polymorphic STR markers flanking the GJB2 gene: D13S141 (~ 39.2 kb centromeric to c.35delG), D13S175 and D13S1853 (~ 84.8 kb and ~ 277.1 kb telomeric to c.35delG, respectively), and intragenic SNP (rs3751385) locating ~ 0.7 kb centromeric from c.35delG were used to reconstruct haplotypes bearing c.35delG. These markers were used previously in relevant studies and were therefore chosen to keep compatibility and enable comparative analysis with already available data. Genotyping of D13S141, D13S175 and D13S1853 was performed in the SB RAS Genomics Core Facility (Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia).

Table 1.

Primer sequences for PCR, fragment analysis and Sanger sequencing

| c.35delG and studied markers (localization, GRCh38.p12)a | Primer sequences | Methods of detection |

|---|---|---|

| c.35delG (GJB2) (13:20189547) |

F: 5′-GGTGAGGTTGTGTAAGAGTTGG-3′ R: 5’-CTGGTGGAGTGTTTGTTCC*CAC-3’ |

PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis (PSDM) with use of Bsc4 I |

| D13S141b (13:20150320–20,150,445) |

F: 5’-GTCCTCCCGGCCTAGTCTTA-3’ (6-FAM) R: 5’-ACCACGGAGCAAAGAACAGA-3’ |

Fragment analysis (GeneScan 500 LIZ) on ABI 3130XL (Applied Biosystems) |

| D13S175b (13:20274367–20,274,479) |

F: 5’-TATTGGATACTTGAATCTGCTG-3’ (PET) R: 5’-TGCATCACCTCACATAGGTTA-3’ |

|

| D13S1853b (13:20466607–20,466,800) |

F: 5’- CAGACTGGCACAAACTTAACTG −3’ (6-FAM) R: 5’- TGTACATCTCTTCTTACATTCATGT − 3’ |

|

| rs3751385 (13:20188817) |

F: 5’-GGCTGGTGAAGTGCAACG-3′ R: 5’-GTAAGCAAACAAACTTTTGAAGTAG-3’ |

PCR-RFLP analysis with use of Nhe I |

aLocalization was taken from the Ensembl Genome browser [53]; b - Specific primer sequences for PCR amplification of microsatellites D13S141, D13S175, and D13S1853 were obtained from the Ensembl genome browser and the NCBI Probe Database [53, 54], one from each primer pairs was labeled with the fluorescent dyes

Statistical analysis

Haplotype frequencies were estimated from observed genotype data using Expectation–Maximization (EM) algorithm of the Arlequin 3.5.2.2 software [43]. Fisher’s exact test (significance level 0.05) was used to compare the allelic and haplotype distributions. Linkage disequilibrium between the marker alleles and c.35delG as well as the age of c.35delG were estimated as described previously [44, 45]. The linkage disequilibrium was calculated as

where δ is the measure of linkage disequilibrium, Pd is the frequency of the marker allele among all chromosomes carrying c.35delG, and Pn is the frequency of the same allele among chromosomes without c.35delG. The age of c.35delG was estimated as

where g is the number of generations from the moment of the c.35delG appearance to the present, Q is the share of chromosomes carrying c.35delG unlinked with the founder haplotype, Pn is the frequency of the allele included in founder haplotype in the population, and Ѳ is the recombinant fraction calculated from the physical distance of the markers from the c.35delG location on the assumption of 1 cM = 1000 kb.

Results

Carrier frequency of c.35delG in Russia

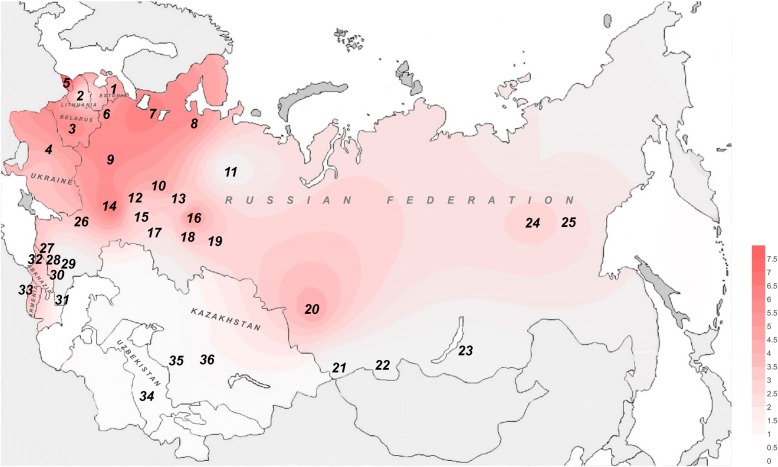

Screening of c.35delG in unrelated hearing individuals (mostly Russians) living in the Novosibirsk region (Western Siberia) has revealed 5 out of 122 examined subjects to be c.35delG carriers (4.1%). These data supplement current information about the c.35delG prevalence in Russia. We have analyzed all available literature data (published up to 2018) on c.35delG carrier frequencies in Russia and in some countries of the former Soviet Union (USSR) which populations undoubtedly contributed to the contemporary population of Russia. The distribution of c.35delG carrier frequencies is presented in Fig. 1. High c.35delG frequencies are observed in the populations of north-western and central parts of Russia with downward trend from west to east.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the c.35delG carrier frequency on the territory of Russia and in some countries of the former Soviet Union. The c.35delG carrier frequencies (%) were obtained from all available data published up to 2018 (Additional file 1: Table S1). Codes from 1 to 36 indicate analyzed samples (region under study and/or ethnicity which were indicated in the original publications). In some cases, c.35delG carrier frequency was calculated by us from the data given in original publications. The maximum value of the c.35delG carrier frequency is used for the figure if there are several data sets for a region or an ethnically stratified sample. Codes 1–4 – Northern and Eastern Europe: 1 – Estonia (4.4–4.5%), 2 – Lithuania (1.0%), 3 – Belarus (3.4–6.2%), 4 – Ukraine (3.3–4.1%); 5–8 - North-Western part of Russia: 5 – residents of Kaliningrad and Kaliningradskaya Oblast’ (7.5%), 6 - residents of Pskov and Pskovskaya Oblast’ (2.0–4.7%), 7 - residents of St. Petersburg and Leningradskaya Oblast’ (3.3–5.9%), 8 - residents of Arkhangelsk and Arkhangelskaya Oblast’ (5.0%); 9–10 - Central part of Russia: 9 – residents of different regions (3.8–5.1%); 10 – Russians (Kirovskaya Oblast’) (3.8%); 11–19 - Volga-Ural region of Russia: 11 – Komi (0%), 12 - Mari (2.0–2.6%), 13 - Udmurts (0.5–3.7%), 14 – Mordvins (5.7–6.2%), 15 – Chuvashes (0–2.6%), 16 - Russians (5.0%), 17 - Tatars (1.0–2.6%), 18 - Bashkirs (0–3.6%), 19 – Russians (Ekaterinburg) (2.2%); 20–25 – Siberia: 20 - Russians (Novosibirsk, Western Siberia) (4.1%), 21 – Altaians (0%), 22 – Tuvinians (0%); 23 - Buryats (0%); 24 - Yakuts (0.4–1.0%), 25 - Russians (Yakutia, Eastern Siberia) (2.5%); 26–31 - South-Western part of Russia (including North Caucasus): 26 - residents of Rostovskya Oblast’ (Russians) (2.9%), 27 – Cherkessians (1.3–2.0%), 28 – Karachays (0.3%), 29 - Ingush (0–2.0%), 30 - Chechens (0–0.7%), 31- Avars (0%); 32–33 - South Caucasus: 32 – Abkhazians (3.8%), 33 – Armenians (3.7%); 34–36 - Central Asia: 34 - Uzbeks (0%), 35 - Kazakhs (0.8%), 36 - Uighurs (0.9%)

Common haplotypes associated with c.35delG in Siberia

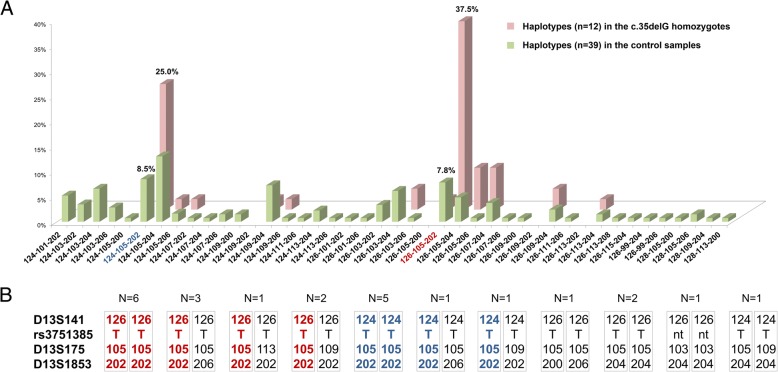

Certain polymorphic STR markers flanking GJB2 are traditionally used for c.35delG haplotype analysis: centromeric D13S141 (~ 39.1 kb from c.35delG), telomeric D13S175 (~ 84.8 kb from c.35delG) and distal telomeric D13S143 (~ 1.5 Mb from c.35delG) [17, 19–29]. Since c.35delG is presumably a very old mutation, a common ancestral haplotype could be observed in even a closest chromosomal locus, therefore instead of the more distal D13S143, we chose the marker D13S1853 that was closer to c.35delG (~ 277.1 kb telomeric), making the haplotype region (D13S141-c.35delG-D13S175-D13S1853) span over ~ 316 kb. Results of D13S141, D13S175, D13S1853 and rs3751385 genotyping in the c.35delG homozygotes and in control individuals from Siberia are summarized in Table 2. Significant differences in allele frequencies of markers D13S141, D13S175, D13S1853 are observed between the c.35delG homozygotes and control subjects (Table 2). Allele T of rs3751385 was only identified in the c.35delG homozygotes showing significant differences (p < 10− 21) between patients and control samples. A strong association of allele T (rs3751385) with c.35delG was also shown in previous studies [18, 22–25, 27, 29]. Twelve and thirty-nine D13S141-D13S175-D13S1853 haplotypes were reconstructed for c.35delG homozygotes and for control samples from Siberia, respectively (Fig. 2A). Two haplotypes, 126–105-202 (37.5%) and 124–105-202 (25.0%), were the most common (52.5% in total) among chromosomes bearing c.35delG in contrast with 7.8% for 126–105-202 and 8.5% for 124–105-202 among wild-type chromosomes (p < 10− 2–10− 5). Based on observed linkage disequilibrium for D13S175 and D13S1853 alleles (Table 2), we have roughly estimated the age of c.35delG in Siberia as ~ 4800 years (D13S1853) or ~ 8100 years (D13S175). It should be noted that an accurate calculation of the c.35delG age is difficult because of many uncertainties, first of all, unknown true recombination frequency of this chromosomal region [18, 22].

Table 2.

Allele frequencies of D13S141, D13S175, D13S1853, and rs3751385 in the c.35delG homozygotes and in the control samples (individuals without c.35delG)

| Markers (location from c.35delG) | Allelea | Homozygotes for c.35delG (n = 24) | Control samples (n = 67) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of alleles | Allele frequency | χ2 | p | δ | Number of alleles | Allele frequency | ||

| D13S141 (~ 39.2 kb centromeric) |

120 | 0 | 0.0000 | – | – | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 |

| 122 | 0 | 0.0000 | – | – | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | |

| 124 | 16 | 0.3333 | 7.8 | 0.0025 | −0.5953 | 78 | 0.5821 | |

| 126 | 32 | 0.6667 | 11 | 0.0006 | 0.4618 | 51 | 0.3806 | |

| 128 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.71 | 0.2121 | −0.0387 | 5 | 0.0373 | |

| Total | 48 | 134 | ||||||

| rs3751385 (intragenic, ~ 0.7 kb centromeric) |

C | 0 | 0.0000 | 76 | < 10 −21 | −5.1652 | 62 | 0.8378 |

| T | 46 | 1.0000 | 76 | < 10 −21 | 1.0000 | 12 | 0.1622 | |

| Total | 46 | 74 | ||||||

| D13S175 (~ 84.8 kb telomeric) |

99 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.002 | 0.5410 | −0.0151 | 2 | 0.0149 |

| 101 | 0 | 0.0000 | 2.1 | 0.0591 | −0.0720 | 9 | 0.0672 | |

| 103 | 2 | 0.0417 | 7.3 | 0.0016 | −0.2467 | 31 | 0.2313 | |

| 105 | 41 | 0.8542 | 28 | < 10 −7 | 0.7588 | 53 | 0.3955 | |

| 107 | 0 | 0.0000 | 2.5 | 0.0427 | −0.0806 | 10 | 0.0746 | |

| 109 | 4 | 0.0833 | 0.45 | 0.2570 | −0.0589 | 18 | 0.1343 | |

| 111 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.002 | 0.5410 | −0.0151 | 2 | 0.0149 | |

| 113 | 1 | 0.0208 | 0.46 | 0.2616 | −0.0413 | 8 | 0.0597 | |

| 115 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.29 | 0.7363 | −0.0076 | 1 | 0.0075 | |

| Total | 48 | 134 | ||||||

| D13S1853 (~ 277.1 kb telomeric) |

200 | 1 | 0.0208 | 0.092 | 0.4074 | −0.0251 | 6 | 0.0448 |

| 202 | 34 | 0.7083 | 23 | < 10 −6 | 0.5842 | 40 | 0.2985 | |

| 204 | 8 | 0.1667 | 16 | < 10 −4 | −0.6920 | 68 | 0.5075 | |

| 206 | 5 | 0.1042 | 0.17 | 0.3497 | −0.0439 | 19 | 0.1418 | |

| 208 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.29 | 0.7363 | −0.0076 | 1 | 0.0075 | |

| Total | 48 | 134 | ||||||

a - Designation of the STR allele corresponds to its size in nucleotides; δ - measure of linkage disequilibrium; the maximum indices of linkage disequilibrium and statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences in allele frequencies between the c.35delG homozygotes and the control samples are in bold

Fig. 2.

The D13S141-D13S175-D13S1853 haplotypes in studied samples. a Distribution of the D13S141-D13S175-D13S1853 haplotypes reconstructed by the Arlequin software (EM algorithm) in the c.35delG homozygotes (pink bars) and in the control samples (green bars) (see explanation in text). n – number of haplotypes. b The D13S141-rs3751385-c.35delG-D13S175-D13S1853 haplotypes found in the c.35delG homozygotes. N - number of individuals. The most frequent haplotypes are highlighted in color: 126-T-105-202 – by red, 124-T-105-202 – by blue; nt - not tested

Discussion

Distribution of the c.35delG carrier frequency in Russia is characterized by pronounced ethno-geographic specificity (Fig. 1). High c.35delG rates are typical for populations of Caucasian origin in north-western part of Russia (up to 7.5% in the Kaliningrad Oblast’ and 5.9% in the Leningrad Oblast’) [46]. The contemporary population of the Kaliningrad Oblast’ represented mainly by Russians (about 80%) was formed as a result of large-scale post-war (after 1945) migration from European regions of the former USSR. A high carrier frequency of c.35delG in rural areas of the Leningrad Oblast’ (5.9%) could probably be attributed to indigenous Finno-Ugric Vepsians, correlating with high c.35delG rates reported for other Finno-Ugrics: 4.4–4.5% in Estonians [12, 47], 5.7–6.2% in Mordvins [30, 48]. The highest carrier frequencies of c.35delG in the Caucasus are observed in Abkhazians (3.8%) [48] and Armenians (3.7%) [49]. Low carrier frequencies of c.35delG or its absence were observed among Turkic-speaking peoples of Volga-Ural region (Tatars, Bashkirs, Chuvashes), Siberia (Altaians, Tuvinians, Yakuts), Central Asia (Kazakhs, Uighurs, Uzbeks), and also in Mongolic-speaking Buryats (Siberia) [39–41, 48, 50]. In Siberia, the c.35delG carrier frequency in Russians varies from 4.1% in Western Siberia (this study) to 2.5% in Yakutia (Eastern Siberia) [41].

Haplotype (D13S141-rs3751385-D13S175-D13S1853) analysis of chromosome 13 in c.35delG homozygous deaf Russian patients from Siberia revealed the two most common haplotypes (126-T-c.35delG-105-202 and 124-T-c.35delG-105-202). It is interesting to compare the common c.35delG haplotypes identified in Siberia with available relevant data for other populations [19, 21, 23–26, 28, 29] (Table 3). Such comparisons are to some extent possible for the c.35delG haplotypes flanked by D13S141 and D13S175 (~ 124 kb). For these markers, the total share of two common c.35delG haplotypes in Siberia, 126-T-c.35delG-105 (56.3%, 27 of 48 chromosomes) and 124-T-c.35delG-105 (29.2%, 14 of 48 chromosomes), reaches 85.5% (Fig. 2B). Unfortunately, unified classification of the D13S141 and D13S175 alleles based on their size in nucleotides or number of dinucleotide (CA) repeats is absent due to different genotyping methods or simple numerical designations for alleles used in previous studies, making accurate comparative analysis hardly possible. Nonetheless, the 105 bp long allele of D13S175 was detected in the most common c.35delG haplotypes in the majority of studies while a broad variety of alleles was observed for D13S141. We were able to compare both allelic size in nucleotides (determined by fragment analysis) and numbers of CA repeats (detected by Sanger sequencing) in two most frequent D13S141 alleles in the c.35delG homozygotes from Siberia (analyzed in this study), Volga-Ural region of Russia (kindly provided by L. Dzhemileva [28]), and Belarus [29]. Fourteen CA repeats (CA14) were found in D13S141 alleles 126, 127, and 125 while thirteen CA repeats (CA13) were found in D13S141 alleles 124, 125, and 123 in DNA samples from Siberia, Belarus, and Volga-Ural region, respectively (Table 3). Thus, the identity of allelic composition of two most frequent haplotypes D13S141-c.35delG-D13S175 (~ 124 kb) was revealed in these geographically remote regions (Table 3). In addition, we assume that the conservative region of c.35delG haplotypes from Siberia may span longer being flanked by D13S141 and D13S1853 (~ 316 kb).

Table 3.

The most common D13S141-c.35delG-D13S175 haplotypes in different populations

| Common haplotypes D13S141-c.35delG-D13S175 (%) |

Geographical region (Ethnicity) | References |

|---|---|---|

| 126 a-105 (56.3%), 124b-105 (29.2%) | Siberia, Russia (mostly Russians) | this study |

| 125 a-105 (67.9%)c, 123b-105 (12.5%)c | Volga-Ural region of Russia (mostly Russians and Tatars) | [28] |

| 127 a-105 (71.8%), 125b-105 (18.2%) | Belarus | [29] |

| 3–4 (90%)c 3–4 (100%)c |

Palestine Israel |

[19] |

| 2–6 (34.5%)c, 3–5 (26.9%)c 2–5 (42.9%)c, 3–5 (33.3%)c |

Eastern Black Sea region, Turkey Other regions of Turkey |

[21] |

| 5 (127)-4 (105) (43%), 5 (127)-4 (105) / 4 (125)-4 (105) (18%) |

Anatolia, Turkey | [23] |

| 125–105 (83.3%)c, 123–105 (10.0%)c | Morocco | [24] |

| 127–105 (61.5%)c, 125–105 (15.6%)c 127–105 (60.3%)c, 125–105 (26.8%)c |

Spain Greece |

[26] |

The contemporary Siberian population of Caucasian origin (mostly Russians) was formed as a result of multiple migration flows from the European part of Russia that started from the first settlement of Siberia by Russians at the end of sixteenth century [51]. Our rough dating of c.35delG expansion into Siberia (about 4800–8100 years ago) could be a reflection of complex processes of early formation stages of the modern European population (including the European part of Russia). These data do not contradict the earlier hypothesis about the c.35delG occurrence in the Middle East or the Mediterranean approximately 10,000–14,000 years ago followed by its spreading with migration flows across Europe [14, 17–27]. However, taking into account the current data on three ancient components in the origin of modern Europeans [52], it cannot be ruled out that c.35delG could also have independently originated among any ancient populations of North-West Europe or anywhere else.

Conclusions

Distribution of the c.35delG carrier frequency in Russia is characterized by pronounced ethno-geographic specificity. High frequencies of c.35delG are observed in the populations living in north-western and central parts of Russia with a downward trend from west to east. The territory of Siberia can be assumed as the north-eastern geographic “end point” of the c.35delG prevalence in Eurasia. Comparative analysis of the c.35delG haplotypes supports the common origin of c.35delG in some regions of Russia (Siberia and Volga-Ural region) and in Eastern Europe (Belarus). A thorough study of the haplotypes associated with c.35delG in populations from different world regions could further elucidate its origin and age.

Additional file

Table S1. With detailed data on c.35delG carrier frequencies on the territory of Russia and in some countries of the former Soviet Union which were obtained from all available papers published up to 2018. This file also includes list of references for Table S1. (DOCX 42 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors are sincerely grateful to all participants of the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Project #0324–2016-0002 of Institute of Cytology and Genetics SB RAS, the RFBR grants #18–34-00166_mol-a (to MZ, VD), #17–29-06016_ofi-m and #14–04-90010 Bel_a (to OP, MZ, MB-Kh, VD, AB, IM); #18–015-00212_А, #18–013-00738_A, #18-05-600035_Arctica (to NB, AS) and by Government Task of Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation #6.1766.2017 (to NB, AS).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GJB2

Gap junction protein, beta-2

- SNP marker

Single nucleotide polymorphic marker

- STR marker

Short tandem repeat marker

Authors’ contributions

Preparation of manuscript: MZ, OP; collection of materials and experimental work: MB-Kh, NB, AS; experimental work: MZ, OSh-O, AB, IM, VD; collection of materials, interpretation of the data and critical review: ND, VM, OP, NB; concept, supervision, interpretation of the data: OP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Study was approved by the Bioethics Commission at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics SB RAS, Novosibirsk (Protocol #9, April 24, 2012) and was in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals who participated in this study or their legal guardians.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marina V. Zytsar, Email: zytzar@yandex.ru

Nikolay A. Barashkov, Email: barashkov2004@mail.ru

Marita S. Bady-Khoo, Email: marita.badyhoo@mail.ru

Olga A. Shubina-Olejnik, Email: oleinik.olga@yahoo.co.uk

Nina G. Danilenko, Email: cytoplasmic@mail.ru

Alexander A. Bondar, Email: alex.bondar@mail.ru

Igor V. Morozov, Email: Mor@niboch.nsc.ru

Aisen V. Solovyev, Email: nelloann@mail.ru

Valeriia Yu. Danilchenko, Email: baler93@mail.ru

Vladimir N. Maximov, Email: medik11@mail.ru

Olga L. Posukh, Email: posukh@bionet.nsc.ru

References

- 1.Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Evans K, Hayden M, Heywood S, Hussain M, Phillips AD, Cooper DN. The human gene mutation database: towards a comprehensive repository of inherited mutation data for medical research, genetic diagnosis and next-generation sequencing studies. Hum Genet. 2017;136:665–677. doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1779-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan DK, Chang KW. GJB2-associated hearing loss: systematic review of worldwide prevalence, genotype, and auditory phenotype. Laryngoscope. 2014; 10.1002/lary.24332. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Liu XZ, Xia XJ, Ke XM, Ouyang XM, Du LL, Liu YH, Angeli S, Telischi FF, Nance WE, Balkany T, et al. The prevalence of connexin 26 (GJB2) mutations in the Chinese population. Hum Genet. 2002;111:394–397. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0811-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohtsuka A, Yuge I, Kimura S, Namba A, Abe S, Van Laer L, Van Camp G, Usami S. GJB2 deafness gene shows a specific spectrum of mutations in Japan, including a frequent founder mutation. Hum Genet. 2003;112(4):329–333. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0889-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morell RJ, Kim HJ, Hood LJ, Goforth L, Friderici K, Fisher R, Van Camp G, Berlin CI, Oddoux C, Ostrer H, et al. Mutations in the connexin 26 gene (GJB2) among Ashkenazi Jews with nonsyndromic recessive deafness. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1500–1505. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamelmann C, Amedofu GK, Albrecht K, Muntau B, Gelhaus A, Brobby GW, Horstmann RD. Pattern of connexin 26 (GJB2) mutations causing sensorineural hearing impairment in Ghana. Hum Mutat. 2001;18:84–85. doi: 10.1002/humu.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.RamShankar M, Girirajan S, Dagan O, Ravi Shankar HM, Jalvi R, Rangasayee R, Avraham KB, Anand A. Contribution of connexin26 (GJB2) mutations and founder effect to non-syndromic hearing loss in India. J Med Genet. 2003;40:e68. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.5.e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez A, del Castillo I, Villamar M, Aguirre LA, González-Neira A, Lopez-Nevot A, Moreno-Pelayo MA, Moreno F. High prevalence of the W24X mutation in the gene encoding connexin-26 (GJB2) in Spanish Romani (gypsies) with autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing loss. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;137A:255–258. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wattanasirichaigoon D, Limwongse C, Jariengprasert C, Yenchitsomanus PT, Tocharoenthanaphol C, Thongnoppakhun W, Thawil C, Charoenpipop D, Pho-iam T, Thongpradit S, et al. High prevalence of V37I genetic variant in the connexin-26 (GJB2) gene among non-syndromic hearing-impaired and control Thai individuals. Clin Genet. 2004;66:452–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barashkov NA, Dzhemileva LU, Fedorova SA, Teryutin FM, Posukh OL, Fedotova EE, Lobov SL, Khusnutdinova EK. Autosomal recessive deafness 1A (DFNB1A) in Yakut population isolate in eastern Siberia: extensive accumulation of the splice site mutation IVS1+1G>a in GJB2 gene as a result of founder effect. J Hum Genet. 2011;56:631–639. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carranza C, Menendez I, Herrera M, Castellanos P, Amado C, Maldonado F, Rosales L, Escobar N, Guerra M, Alvarez D, et al. A Mayan founder mutation is a common cause of deafness in Guatemala. Clin Genet. 2016;89:461–465. doi: 10.1111/cge.12676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gasparini P, Rabionet R, Barbujani G, Melçhionda S, Petersen M, Brøndum-Nielsen K, Metspalu A, Oitmaa E, Pisano M, Fortina P, et al. High carrier frequency of the 35delG deafness mutation in European populations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:19–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahdieh N, Rabbani B. Statistical study of 35delG mutation of GJB2 gene: a meta-analysis of carrier frequency. Int J Audiol. 2009;48:363–370. doi: 10.1080/14992020802607449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucotte G, Diéterlen F. The 35delG mutation in the connexin 26 gene (GJB2) associated with congenital deafness: European carrier frequencies and evidence for its origin in ancient Greece. Genet Test. 2005;9:20–25. doi: 10.1089/gte.2005.9.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrasquillo MM, Zlotogora J, Barges S, Chakravarti A. Two different connexin 26 mutations in an inbred kindred segregating non-syndromic recessive deafness: implications for genetic studies in isolated populations. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2163–2172. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denoyelle F, Weil D, Maw MA, Wilcox SA, Lench NJ, Allen-Powell DR, Osborn AH, Dahl HH, Middleton A, Houseman MJ, et al. Prelingual deafness: high prevalence of a 30delG mutation in the connexin 26 gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2173–2177. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tekin M, Akar N, Cin S, Blanton SH, Xia XJ, Liu XZ, Nance WE, Pandya A. Connexin 26 (GJB2) mutations in the Turkish population: implications for the origin and high frequency of the 35delG mutation in Caucasians. Hum Genet. 2001;108:385–389. doi: 10.1007/s004390100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Laer L, Coucke P, Mueller RF, Caethoven G, Flothmann K, Prasad SD, Chamberlin GP, Houseman M, Taylor GR, Van de Heyning CM, et al. A common founder for the 35delG GJB2 gene mutation in connexin 26 hearing impairment. J Med Genet. 2001;38:515–518. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.8.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahin H, Walsh T, Sobe T, Lynch E, King MC, Avraham KB, Kanaan M. Genetics of congenital deafness in the Palestinian population: multiple connexin 26 alleles with shared origins in the Middle East. Hum Genet. 2002;110:284–289. doi: 10.1007/s00439-001-0674-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothrock CR, Murgia A, Sartorato EL, Leonardi E, Wei S, Lebeis SL, Yu LE, Elfenbein JL, Fisher RA, Friderici KH. Connexin 26 35delG does not represent a mutational hotspot. Hum Genet. 2003;113(1):18–23. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0944-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balci B, Gerçeker FO, Aksoy S, Sennaroğlu G, Kalay E, Sennaroğlu L, Dinçer P. Identification of an ancestral haplotype of the 35delG mutation in the GJB2 (connexin 26) gene responsible for autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing loss in families from the eastern Black Sea region in Turkey. Turk J Pediatr. 2005;47(3):213–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belguith H, Hajji S, Salem N, Charfeddine I, Lahmar I, Amor MB, Ouldim K, Chouery E, Driss N, Drira M, et al. Analysis of GJB2 mutation: evidence for a Mediterranean ancestor for the 35delG mutation. Clin Genet. 2005;68:188–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tekin M, Boğoclu G, Arican ST, Orman MN, Tastan H, Elsobky E, Elsayed S, Akar N. Evidence for single origins of 35delG and delE120 mutations in the GJB2 gene in Anatolia. Clin Genet. 2005;67:31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abidi O, Boulouiz R, Nahili H, Imken L, Rouba H, Chafik A, Barakat A. The analysis of three markers flanking GJB2 gene suggests a single origin of the most common 35delG mutation in the Moroccan population. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:971–974. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kokotas H, Van Laer L, Grigoriadou M, Iliadou V, Economides J, Pomoni S, Pampanos A, Eleftheriades N, Ferekidou E, Korres S, et al. Strong linkage disequilibrium for the frequent GJB2 35delG mutation in the Greek population. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:2879–2884. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kokotas H, Grigoriadou M, Villamar M, Giannoulia-Karantana A, del Castillo I, Petersen MB. Hypothesizing an ancient Greek origin of the GJB2 35delG mutation: can science meet history? Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14:183–187. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2009.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norouzi V, Azizi H, Fattahi Z, Esteghamat F, Bazazzadegan N, Nishimura C, Nikzat N, Jalalvand K, Kahrizi K, Smith RJ, et al. Did the GJB2 35delG mutation originate in Iran? Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:2453–2458. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dzhemileva LU, Posukh OL, Barashkov NA, Fedorova SA, Teryutin FM, Akhmetova VL, Khidiyatova IM, Khusainova RI, Lobov SL, Khusnutdinova EK. Haplotype diversity and reconstruction of ancestral haplotype associated with the c.35delG mutation in the GJB2 (Cx26) gene among the Volgo-Ural populations of Russia. Acta Nat. 2011;3(3):52–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shubina-Olejnik OA. Genetic nature of non-syndromic sensorineural hearing impairment in Belarus. Institute of Genetics and Cytology, National Academy of Sciences, Minsk, Belarus: Dissertation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khidiiatova IM, Dzhemileva LU, Khabibulin RM, Khusnutdinova EK. Frequency of the 35delG mutation of the connexin 26 gene (GJB2) in patients with non-syndromic autosome-recessive deafness from Bashkortostan and in ethnic groups of the Volga-Ural region. Mol Biol (Mosk) 2002;36(3):438–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markova TG, Megrelishvilli SM, Zaĭtseva NG, Shagina IA, Poliakov AV. DNA diagnosis in congenital and early childhood hypoacusis and deafness. Vestn Otorinolaringol. 2002;6:12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shokarev RA, Amelina SS, Kriventsova NV, Elchinova GI, Khlebnikova OV, Tverskaya SM, Bliznetz EA, Polyakov AV, Zinchenko RA. Genetic-epidemiological and molecular study of hereditary deafness in Rostov province. Medizinskaya genetika. 2005;4:556–565. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markova TG, Poliakova AV, Kunel'skaia NL. Clinical picture of hearing defects caused by Cx26 gene mutations. Vestn Otorinolaringol. 2008;2:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osetrova AA, YeI S, Rossinskaya TG, Galkina VA, Zinchenko RA. Investigation of genetic aspects of congenital and early childhood deafness in specialized schools for children with impaired hearing of Kirov region, Russia. Medizinskaya genetika. 2010;9:30–40. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bliznets EA, Galkina VA, Matiushchenko GN, Kisina AG, Markova TG, Poliakov AV. Changes in the connexin 26 (GJB2) gene in Russian patients with hearing disorders: results of long-term molecular diagnostics of hereditary nonsyndromic deafness. Genetika. 2012;48(1):112–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zinchenko RA, Osetrova AA, Sharonova EI. Hereditary deafness in Kirov oblast: estimation of the incidence rate and DNA diagnosis in children. Genetika. 2012;48(4):542–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lalaiants MR, Markova TG, Bakhshinian VV, Bliznets EA, Poliakov AV, Tavartikiladze GA. The audiological phenotype and the prevalence of GJB2-related sensorineural loss of hearing in the infants suffering acoustic disturbances. Vestn Otorinolaringol. 2014;2:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bliznetz EA, Lalayants MR, Markova TG, Balanovsky OP, Balanovska EV, Skhalyakho RA, Pocheshkhova EA, Nikitina NV, Voronin SV, Kudryashova EK, et al. Update of the GJB2/DFNB1 mutation spectrum in Russia: a founder Ingush mutation del(GJB2-D13S175) is the most frequent among other large deletions. J Hum Genet. 2017;62:789–795. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2017.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Posukh O, Pallares-Ruiz N, Tadinova V, Osipova L, Claustres M, Roux AF. First molecular screening of deafness in the Altai Republic population. BMC Med Genet. 2005;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bady-Khoo MS, Bondar AA, Morozov IV, Zytsar MV, Mikhalskaya VYu, Skidanova OV, Barashkov NA, Mongush, RSh, Omzar OS, Tukar VM, et al. Study of hereditary forms of hearing loss in the Republic of Tyva. II. Evaluation of the mutational spectrum of the GJB2 (Cx26) gene and its contribution to the etiology of hearing loss Medizinskaya genetika. 2014;13:30–40. [Article in Russian].

- 41.Barashkov NA, Pshennikova VG, Posukh OL, Teryutin FM, Solovyev AV, Klarov LA, Romanov GP, Gotovtsev NN, Kozhevnikov AA, Kirillina EV, et al. Spectrum and frequency of the GJB2 gene pathogenic variants in a large cohort of patients with hearing impairment living in a subarctic region of Russia (the Sakha Republic). PLoS One. 2016; 10.1371/journal.pone.0156300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Storm K, Willocx S, Flothmann K, Van Camp G. Determination of the carrier frequency of the common GJB2 (connexin-26) 35delG mutation in the Belgian population using an easy and reliable screening method. Hum Mutat. 1999;14:263–266. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)14:3<263::AID-HUMU10>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Excoffier L, Lischer HE. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10(3):564–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bengtsson BO, Thomson G. Measuring the strength of associations between HLA antigens and diseases. Tissue Antigens. 1981;18:356–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1981.tb01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Risch N, de Leon D, Ozelius L, Kramer P, Almasy L, Singer B, Fahn S, Breakefield X, Bressman S. Genetic analysis of idiopathic torsion dystonia in Ashkenazi Jews and their recent descent from a small founder population. Nat Genet. 1995;9:152–159. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhuravskiy SG, Ivanov SA, Taraskina AE, Grinchik OV, Kurus AA. Prevalence of GJB2 gene mutation 35delG among healthy population of Northwest Region of Russia. Meditsinskiy Akademicheskiy Zhurnal. 2009;9:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teek R, Kruustük K, Zordania R, Joost K, Reimand T, Möls T, Oitmaa E, Kahre T, Tõnisson N, Ounap K. Prevalence of c.35delG and p.M34T mutations in the GJB2 gene in Estonia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:1007–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dzhemileva LU, Barashkov NA, Posukh OL, Khusainova RI, Akhmetova VL, Kutuev IA, Gilyazova IR, Tadinova VN, Fedorova SA, Khidiyatova IM, et al. Carrier frequency of GJB2 gene mutations c.35delG, c.235delC and c.167delT among the populations of Eurasia. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:749–754. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bliznetz EA, Sarkisian TF, Manoukyan TÀ, Bakhshinyan VV, Polyakov AV. GJB2 caused hearing loss in Armenians. Medizinskaya genetika. 2012;5:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petrina NE, Bliznetz EA, Zinchenko RA, AKh.-M M, Petrova NA, Vasilyeva TA, Chudakova LV, Petrin AN, Polyakov AV, Ginter EK. The frequency of GJB2 gene mutations in patients with hereditary non-syndromic sensoneural hearing loss in eight populations of Karachay-Cherkess Republic. Medizinskaya genetika. 2017;16:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okladnikov AP, editor. Istoriya Sibiri s drevneishikh vremen do nashikh dnei [History of Siberia since ancient times to the present day]. Leningrad: Nauka; 1968. [in Russian]

- 52.Lazaridis I, Patterson N, Mittnik A, Renaud G, Mallick S, Kirsanow K, Sudmant PH, Schraiber JG, Castellano S, Lipson M, et al. Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature. 2014;513:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nature13673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ensemble genome browser. http://www.ensembl.org. Accessed Mar 2018.

- 54.NCBI Probe Database. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/probe. Accessed Mar 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. With detailed data on c.35delG carrier frequencies on the territory of Russia and in some countries of the former Soviet Union which were obtained from all available papers published up to 2018. This file also includes list of references for Table S1. (DOCX 42 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.