SUMMARY

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) regulates mRNA metabolism and translation, serving as an important source of post-transcriptional regulation. To date, the functional consequences of m6A deficiency within the adult brain have not been determined. To achieve m6A deficiency, we deleted Mettl14, an essential component of the m6A methyltransferase complex, in two related yet discrete mouse neuronal populations: striatonigral and striatopallidal. Mettl14 deletion reduced striatal m6A levels without altering cell numbers or morphology. Transcriptome-wide profiling of m6A-modified mRNAs in Mettl14-deleted striatum revealed downregulation of similar striatal mRNAs encoding neuron- and synapse-specific proteins in both neuronal types, but striatonigral and striatopallidal identity genes were uniquely downregulated in each respective manipulation. Upregulated mRNA species encoded non-neuron-specific proteins. These changes increased neuronal excitability, reduced spike frequency adaptation and profoundly impaired striatal-mediated behaviors. Using viral-mediated, neuron-specific striatal Mettl14 deletion in adult mice, we further confirmed the significance of m6A in maintaining normal striatal function in the adult mouse.

eTOC blurb

Koranda et al. demonstrate Mettl14 is indispensable for m6A mRNA methylation in the adult mammalian brain. Striatal Mettl14 deficiency decreases m6A-tagging, altering the epitranscriptome profile. Mettl14 deficiency impairs behavior and alters intrinsic neuronal firing in the absence of morphological changes.

INTRODUCTION

The discovery of reversible m6A mRNA methylation (m6A-tagging) has revealed an important layer of post-transcriptional gene regulation (Meyer and Jaffrey, 2014; Zhao et al., 2017). m6A-tagging affects almost every aspect of mRNA metabolism including splicing, export, localization, translation efficiency and stability (Liu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014a; 2015). Recent studies have shown that constitutive knockout of Mettl14, a key element of the m6A methyltransferase complex (Liu et al., 2014), is embryonic lethal while conditional knockout of Mettl14 in neural progenitor cells disrupts cortical development and leads to premature death in mice (Yoon et al., 2017; Wang et al. 2018). Because m6A levels in mouse brain tissue are relatively low through embryogenesis but drastically increase by adulthood (Meyers et al., 2012), it remains possible that m6A-tagging plays a unique role in the adult brain. Indeed, studies examining the consequences of Fto manipulation, an m6A demethylase (Jia et al., 2012), suggest that m6A -tagging plays an important role in learning and behavior (Hess et al., 2013; Walters et al., 2013; Widagdo et al., 2016; Walters et al., 2017). However, Fto has functions aside from m6A demethylation (Jia et al., 2008; Mauer et al., 2017), and Fto encodes only one of two known m6A demethylases (Zheng et al., 2013). Thus, the functional consequences of Fto manipulations could arise from causes other than changes in m6A-tagging.

Using cell-type-specific genetic deletion or brain-region-specific AAV-mediated deletion of Mettl14, here we study the necessity of m6A-tagging in neurons by examining the functional consequences of m6A loss in the adult mammalian brain.

RESULTS

Conditional deletion of Mettl14 in striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons decreases m6A methylation and alters mRNA expression

To bypass the detrimental effects of Mettl14 deletion in early embryonic development (Yoon et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018), we crossed mice carrying a conditionally removable allele of Mettl14 (M14f/f) with mice expressing Cre recombinase under control of either the dopamine D1 receptor (D1R) promoter (D1R-fM14exp) or ADORA2A promoter (D2R-fM14exp) to delete Mettl14 in dopamine D1R-expressing striatonigral neurons or dopamine D2 receptor (D2R)-expressing striatopallidal neurons, respectively. These cells represent the two prominent striatal projection neuron types with roughly even distribution throughout the striatum. Both D1R- and D2R-fM14exp mice were viable. Adult mutant mice (2–6 months old) were not obviously distinguishable from littermate controls (referred herein as D1R-fM14ctrl and D2R-fM14ctrl), although motor impairments became more obvious in older mice.

Deletion of either striatonigral or striatopallidal Mettl14 significantly decreased striatal cells double-labeled for both NeuN and METTL14 (D1R: t=7.608, p=0.0032; D2R: t=3.2092, p=0.0326), without affecting overall levels of NeuN in either manipulation (Fig. S1A&S1B, D1R: t=−0.1079, p=0.9197; D2R: t=0.3825, p=0.7216). We also found intact striatonigral projections to the substantia nigra pars reticulata in D1R-fM14exp mice (Fig. S1C) and intact striatopallidal projections to the globus pallidus in D2R-fM14exp mice (Fig. S1C).

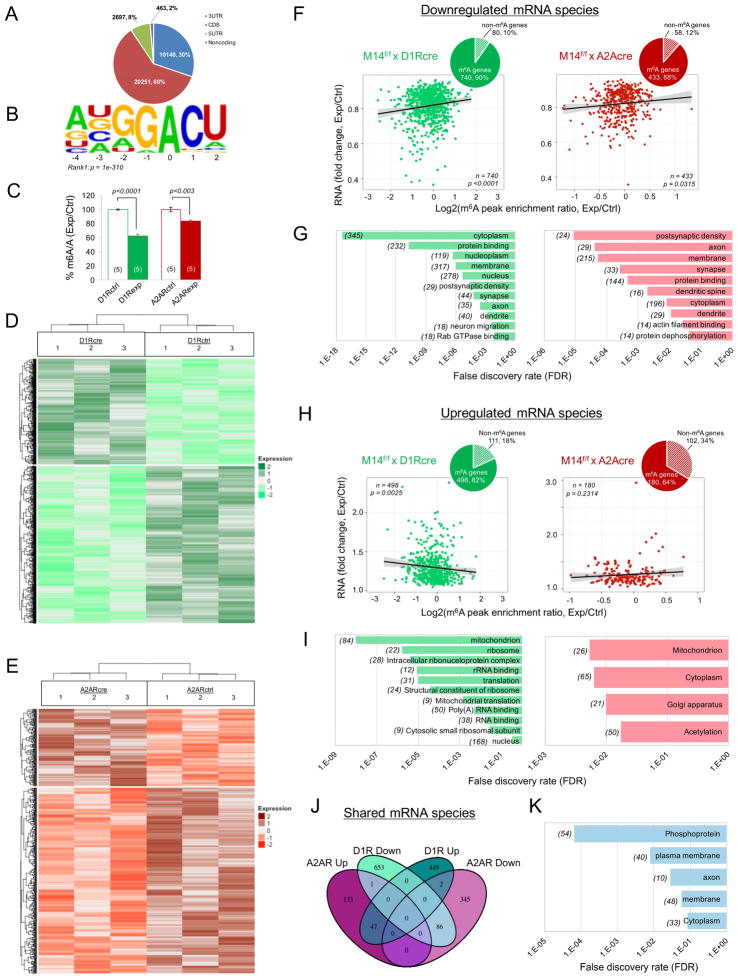

m6A mRNA immunoprecipitation followed by RNA sequencing (m6A-seq) revealed more than 33,500 putative m6A sites enriched in more than 11,000 mRNA species in control striatum, with a transcriptome-wide distribution and preferred consensus motif similar to previous reports (Meyer et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2014; Fig. 1A&1B). Mettl14 deletion in either cross significantly reduced overall m6A levels determined by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 1C, D1R: t=18.34, p<0.0001; D2R: t=4.402, p=0.0033). Loss of striatonigral Mettl14 resulted in the downregulation of 740 m6A-containing mRNAs (Fig. 1D&1F) and upregulation of 498 m6A-containing mRNAs (Fig. 1D,1F&1H). The magnitude of change in both downregulated (Fig. 1F, t=3.6157, p=0.0003) and upregulated (Fig. 1H, t=2.288, p=0.0225) mRNAs positively correlated with magnitude of decrease in m6A peak enrichment in D1R-fM14exp mice (Table 1S), meaning that transcripts with the largest decrease in m6A mRNA enrichment score in experimental mice relative to control mice also showed the greatest degree of change in mRNAs (either up or down).

Figure 1. Mettl14 deletion in striatonigral or striatopallidal neurons alters striatal epitranscriptome.

A) Transcriptome-wide distribution of m6A peaks of control samples. Number and percent of m6A peaks are shown. B) Consensus motif of m6A sites identified in m6A peaks of control samples. C) LC-MS/MS showing knockdown of striatal m6A levels. Data normalized to control percent methylated adenosine. D & E) Clustering and heat maps showing mRNA levels in three experimental and control mice following striatonigral (D) or striatopallidal (E) Mettl14 deletion. Relative mRNA expression level is represented in color. Only genes with log2 of enrichment fold of m6A peaks m6A-seq > 1 in controls and significant changes (p<0.05) in mRNA expression levels are shown. F) Correlation between (1) the fold change (FC) of RNA abundance in experimental relative to control mice and (2) the log2 ratio of m6A enrichment (experimental/control) in significantly downregulated mRNAs. P values were calculated from a Pearson’s product-moment correlation. left: D1R-fM14exp, right: D2R-fM14exp. Insets: Pie chart showing significantly altered m6A-containing and non-m6A-containing mRNA species. G) GO analysis of mRNAs with RPKM ratio< 1 and p <0.05. left: D1R-fM14exp, right: D2R-fM14exp. Number of genes in each category shown in parentheses. H) Correlation analysis as described for (F) using significantly upregulated mRNAs. left: D1R-fM14exp, right: D2R-fM14exp. Insets: Pie chart showing significantly altered m6A-containing and non-m6A-containing mRNA species. I) GO analysis with FC > 1 and p < 0.05. left: D1R-fM14exp, right: D2R-fM14exp. Number of genes in each category shown in parentheses. J) Venn diagram showing overlap of genes with significant changes in mRNA expression in both D1R-fM14exp and D2R-fM14exp mice. K) GO analysis of genes with significantly downregulated mRNA species in both D1R-fM14exp and D2R-fM14exp mice. Number of genes in each category shown in parentheses. See also Fig. S1 and Table S1.

In D2R-fM14exp mice, we similarly found a greater number of downregulated m6A-containing mRNAs (Fig. 1E&1F, n=433) than upregulated m6A mRNA species (Fig. 1E&1H, n=180). Similar to D1R-fM14exp mice, the degree of downregulation of mRNA species correlated with loss of m6A enrichment (Fig. 1F, t=2.1575, p=0.03151). However, we found no significant correlation between upregulation of mRNA species and m6A enrichment (Fig. 1H, t=1.2007, p=0.2314, Table S1).

Gene ontology (GO) analyses revealed that genes associated with downregulated mRNAs containing m6A sites were enriched in neuron-specific compartments including the synapse, postsynaptic membrane, axon and dendrites in both D1R- and D2R-fM14exp mice (Fig. 1G). Moreover, we found downregulation of striatal mRNAs containing m6A sites in numerous genes important for synaptic plasticity, including Homer1 and Cdk5r1 in both D1R- and D2R-fM14exp mice. Despite these shared changes in mRNAs encoding neuronal and synaptic proteins, only D1R-fM14exp mice showed significantly reduced expression of striatonigral identity genes encoding the precursors of substance-P (Tac1, t=3.806, p=0.0190) and dynorphin (Pdyn, t=5.288, p=0.0061). Likewise, only D2R-fM14exp mice showed decreased mRNA expression of the striatopallidal identity genes for the enkephalin precursor (Penk t=7.162, p=0.0029) and D2R (Drd2, t=3.389, p=0.02805). All of these identity genes contain m6A consensus sequences. In contrast, GO analyses of genes containing m6A sites that resulted in upregulation of striatal mRNA expression in D1R-fM14exp mice revealed enrichment primarily in metabolism, ribosomal machinery, and translation (Fig. 1I). In D2R-fM14exp mice, we found almost no significant enrichment terms when upregulated mRNA species were subjected to GO analysis (Fig. 1I).

Subsequent analysis revealed a subset of 86 genes (Fig. 1J) downregulated in both D1R- and D2R-fM14exp mice with GO enrichment in membrane, axon and phosphoproteins (Fig. 1K), while 47 genes were upregulated in both D1R- and D2R-fM14exp mice. Importantly, only 3 genes with significant changes in mRNA expression in both D1R- and D2R-fM14exp mice showed altered expression in opposite directions (e.g. upregulated in D1R-fM14exp, but downregulated in D2R-fM14exp mice), suggesting lack of Mettl14 alters mRNA expression in these two neural populations similarly.

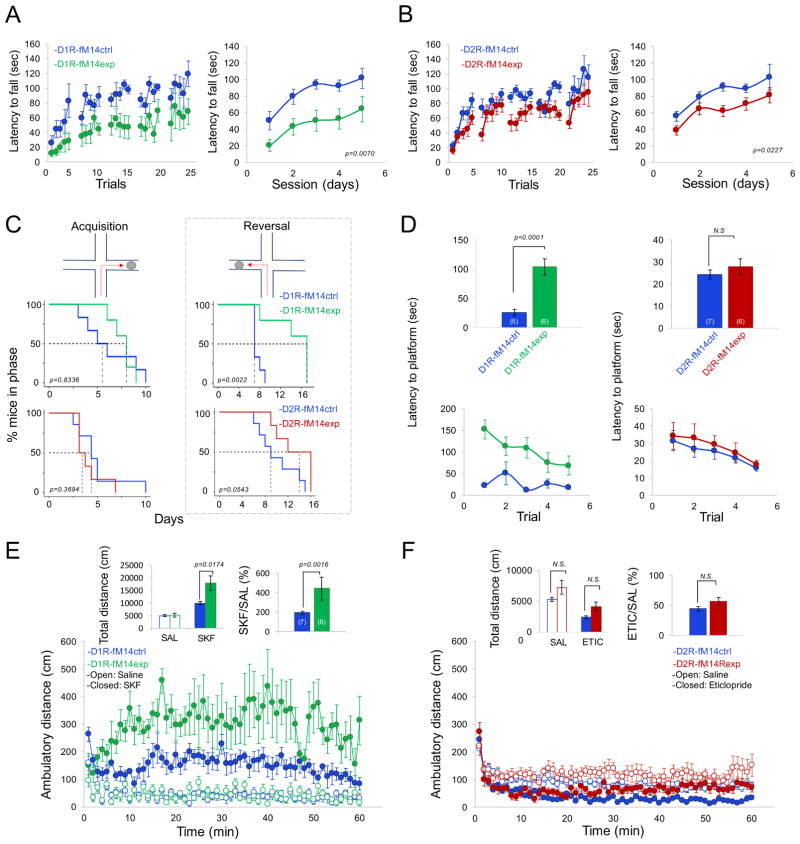

Striatonigral and striatopallidal Mettl14 deletion impairs striatal-mediated performance and learning

To examine the behavioral consequences of Mettl14 deletion, we focused on well-established striatum-dependent behaviors, which require intact cortico-striato-thalamic circuitry. We used the accelerating rotarod to assess sensorimotor learning and the water cross maze to assess response-reversal learning. Impairments were observed in sensorimotor learning (D1R: Fig. 2A, genotype main effect: F(1,52)=10.22, p=0.0070; D2R: Fig. 2B, genotype main effect: F(1,120)=4.615, p=0.0227) and reversal learning (Fig. 2C right, D1R: Log-rank Mantel-Cox, Chi-squared=9.356, p=0.0022; D2R: Log-rank Mantel-Cox, Chi-squared=3.704, p=0.0543) in both D1R- and D2R-fM14exp mice, while initial acquisition of response learning was normal (Fig. 2C left, D1R: Log-rank Mantel-Cox, Chi-squared=0.004413, p=0.8336; D2R: Log-rank Mantel-Cox, Chi-squared=0.8056, p=0.3694). Gross motor performance was then assessed using a visible platform task. We found significantly increased latency to reach the platform in mice with striatonigral (Fig. 2D left, t=−6.421, p=0.0016) but not striatopallidal (Fig. 2D right, t=−0.8932, p=0.3901) Mettl14 deletion.

Figure 2. Lack of Mettl14 in striatal subpopulations alters striatal-mediated behavior.

A and B) Latency to fall from the accelerating rotarod in 12 week old mice. Left: Mice were given 5 trials per day. Right: Each data point represents the average of 5 trials per training session. (A) D1R-fM14ctrl, n = 7, D1R-fM14exp, n =8; (B) D2R-fM14ctrl, n = 17, D2R-fM14exp, n = 14. C) Response learning acquisition (left) and reversal learning (right) in mice with Mettl14 deleted in striatonigral (top) and striatopallidal (bottom) neurons using water-cross maze. Survival plots show percent mice remaining below learning criterion. D1R-fM14exp: n = 6; D1R-fM14ctrl: n =5. D2R-fM14exp: n=6, D2R-fM14ctrl: n=7. D) Latency to reach a visible platform in the water maze for entire session (top) and across 5 trials (bottom). Left: D1R-fM14exp, n = 6; D1R-fM14ctrl, n =5. Right: D2R-fM14exp: n=6, D2R-fM14ctrl: n=7. E) Locomotor response of D1R-fM14exp and control mice to a single injection of the D1R agonist SKF82197 (8.0 mg/kg) across 1 min bins (bottom). Total ambulatory distance across 60 minutes (top, left) and % change in locomotion following SKF81297 injection relative to saline (top, right). D1R-fM14exp: n = 8; D1R-fM14ctrl: n =7. F) Locomotor response of D2R-fM14exp and control mice to a single injection of the D2R antagonist eticlopride (0.16 mg/kg) across 1 min bins (bottom). Total ambulatory distance across 60 minutes (top, left) and % change in locomotion following eticlopride injection relative to saline (top, right). D2R-fM14exp: n = 14; D2R-fM14ctrl: n =17. All data expressed as mean ± S.E.M.

Striatonigral and striatopallidal Mettl14 deletion increases sensitivity to dopaminergic drugs

We next administered pathway-specific drugs to evaluate locomotor responsivity. Baseline locomotor activity did not differ in either D1R-fM14exp (Fig. 2E, genotype: F(1.767)=0.0725, p=0.7920; genotype x time interaction: F(59,767)=0.9441, p=0.5963) or D2R-fM14exp mice (Fig. 2F, genotype: F(1.1711)=2.970, p=0.955; genotype x time interaction: F(59,1711)=0.1.326, p=0.0512), though there was a trend toward hyperactivity in D2R-fM14exp mice. D1R-fM14exp mice showed significantly increased sensitivity to the selective D1R agonist SKF-81297 (Fig. 2E, genotype x drug: F(1,13)=7.029, p=0.0200). In contrast, D2R-fM14exp mice showed almost normal sensitivity to the selective D2R antagonist eticlopride (Etic: Fig. 2F, genotype x drug: F(1,28)=0.0400, p=0.8430). We chose to treat D2R-fM14exp mice with an antagonist rather than an agonist due to a potential confound arising from D2R agonist activation of D2 autoreceptors, which dramatically reduce dopamine release.

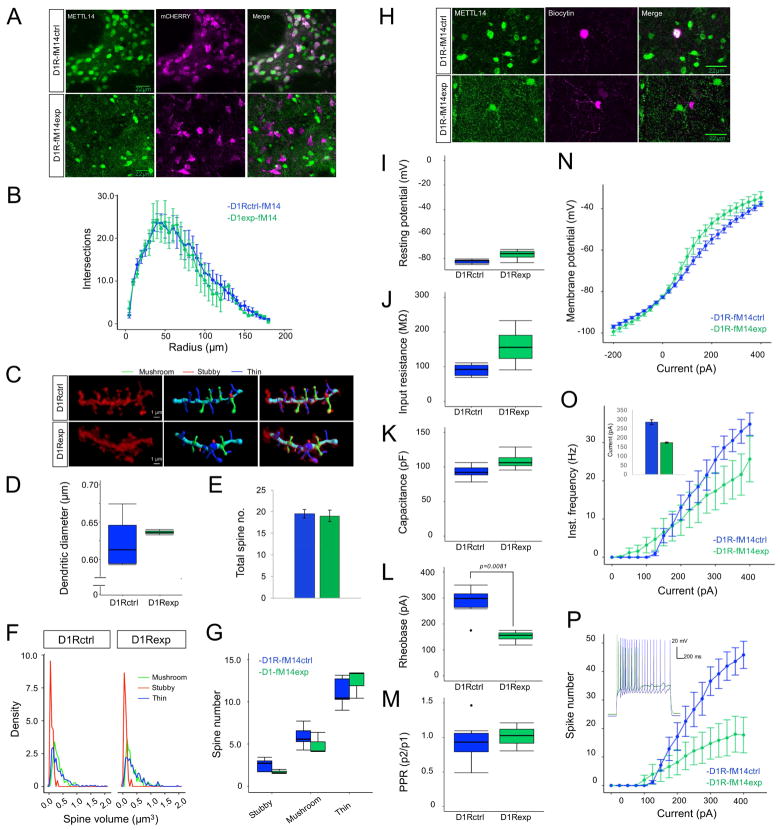

Morphology of striatonigral neurons is normal following Mettl14 deletion

The epitranscriptomic and behavioral analyses suggest that Mettl14 deletion from specific neuronal populations alters neuronal function. To study how neuron-specific Mettl14 deletion may alter neuronal structure and function, we first examined basic morphological properties in the striatonigral pathway of D1R-fM14exp mice. We focused on the striatonigral-specific deletion as we observed a more severe phenotype in these mice. To visualize dendritic spine morphology in D1R neurons (Fig. 3), we injected an AAV encoding Cre-dependent mCherry into the dorsal striatum of adult D1R-fM14exp and M14f/−;D1Rcre+ control (D1R-fM14ctrl) mice. Immunohistochemistry revealed a lack of METTL14 in mCherry-positive striatal cells in D1R-fM14exp mice (Fig. 3A). We found no difference in dendritic branching (Fig. 3B), dendritic diameter (Fig. 3C&3D), total spine number (Fig. 3C&3E), or number or volume of stubby, mushroom and thin dendritic spines (Fig. 3F&3G, See Table S2 for statistics).

Figure 3. Morphological and physiological analysis of striatonigral neurons lacking Mettl14 A).

Representative immunohistochemistry showing Mettl14 deletion in mCherry labelled D1R-expressing striatal neurons. B) Sholl analysis assessing dendritic branching as a function of distance from soma. C) Representative dendrites from showing sections of an mCherry-filled dendrite (left), reconstruction of dendrites (middle), and overlay of the reconstruction on the actual dendrite (right). D) Quantification of dendritic diameter. E) Total spine number. F) Frequency plots of spine volume. G) Average number of spines according to classification. D1R-fM14ctrl: n = 35 dendrites, 5 mice. D1R-fM14exp: n = 21 dendrites, 3 mice. H) Representative cells showing presence of METTL14 in a recorded control cell and the absence of METTL14 in a recorded experimental cell filled with biocytin. Intrinsic membrane properties of D1R-fM14exp mice, including (I) resting membrane potential, (J) input resistance, (K) capacitance, (L) rheobase and (M) paired pulse ratio (PPR). D1R-fM14exp: n = 15 cells, 4 mice. D1R-fM14ctrl: n = 23 cells, 6 mice. N) Membrane responses to current injection. D1R-fM14exp: n = 11 cells, 4 mice. D1R-fM14ctrl: n = 18 cells, 6 mice. O) Instantaneous firing rate responses to current injection. Inset: Average current to elicit train of action potentials. Cells that did not generate a train of spikes were not considered. D1R-fM14exp: n = 11 cells, 4 mice. D1R-fM14ctrl: n = 15 cells, 6 mice. P) Average spike number in response to current injection. Inset: Example of a trace elicited from cells with an ISI of ~14 Hz following 325 pA current injection. D1R-fM14exp: n = 11 cells, 4 mice. D1R-fM14ctrl: n = 15 cells, 6 mice. Box plot whiskers show min to max values. Black points indicate outliers. Data shows average across each mouse ± S.E.M. See also Table S2.

Deletion of Mettl14 in striatonigral neurons alters neuronal excitability

To determine if Mettl14 deletion alters intrinsic physiological properties of striatonigral neurons, we performed whole-cell recordings in mCherry-labeled D1 neurons. Recorded cells were filled with biocytin to confirm lack of METTL14 (Fig. 3H). We found no difference in passive membrane properties (Fig. 3I–K, Table S2) including resting membrane potential, input resistance, and capacitance. However, a leftward shift in the current-voltage relationship, while not significant, was observed in D1R-fM14exp mice (Fig. 3N). Striatonigral Mettl14 deletion also significantly lowered the current threshold to generate both a single action potential (rheobase: Fig. 3L) and a train of action potentials (Fig. 3O, inset), suggesting Mettl14 deletion increases neuronal excitability. Interestingly, instantaneous firing frequency did not differ (Fig. 3O), yet the number of spikes at a given frequency was significantly lower in D1R-fM14exp mice (Fig. 3P), suggesting Mettl14 deletion alters spike frequency adaptation. These differences are likely due to altered intrinsic striatonigral signaling rather than inputs to striatonigral neurons as we found no difference in paired pulse ratio (Fig. 3M).

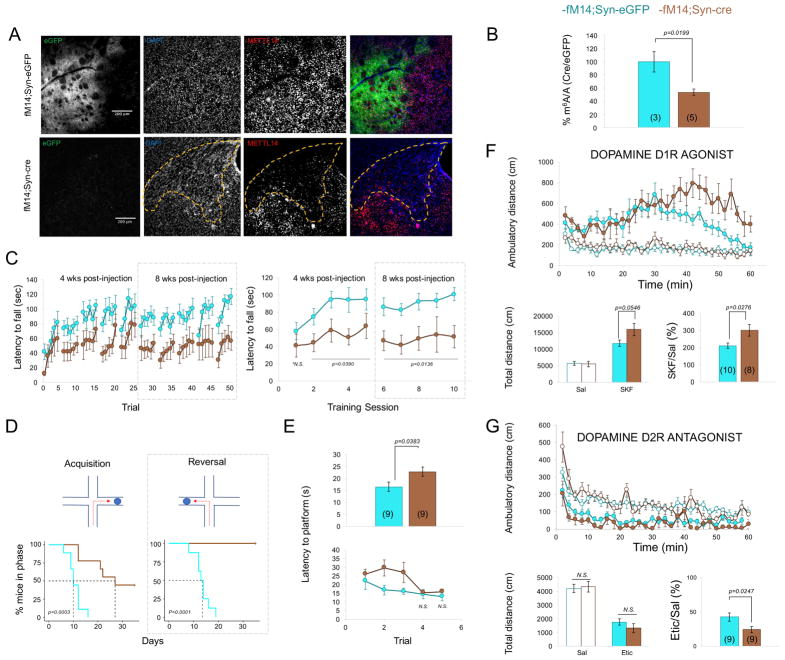

Viral-mediated deletion of Mettl14 in adult striatal neurons reduces m6A methylation, impairs striatal learning and alters dopamine signaling

Because D1Rcre and A2ARcre direct Cre expression starting in late embryonic development (Sillivan and Konradi, 2011, Weaver, 1993), data collected with these mouse lines may include developmental effects of Mettl14 deletion. To strictly test the necessity of Mettl14 in adult neurons, we injected an AAV encoding Cre or eGFP under control of the synapsin promoter (Syn-Cre or Syn-eGFP) bilaterally into the dorsal striatum of adult M14f/f mice. Viral-mediated Mettl14 deletion resulted in a substantial loss of METTL14 protein (Fig. 4A) and reduced striatal m6A levels (Fig. 4B, t=3.14, p=0.0199), providing the first definitive in vivo evidence that Mettl14 is indispensable for m6A modification of mRNAs in the adult brain. The remaining m6A-modified mRNA in the striatum likely reflects non-neuronal cells as well as neurons outside the range of AAV infection in the dorsal striatum. Transcriptome-wide m6A profiling showed no correlation between degree of change in m6A-enrichment and fold change of mRNA levels and returned no significantly enriched GO terms in Syn-Cre mice relative to controls (Fig. S2 and Table S1). Lack of significance may be due to a loss in signal-to-noise stemming from the inclusion of striatal cells outside the injection site. Moreover, the striatal network may not sufficiently adapt after only a few weeks of m6A deficiency.

Figure 4. Viral-mediated deletion of Mettl14 in the dorsal striatum of adult mice alters striatal learning and response to dopaminergic drugs.

A) Representative pictures showing deletion of METTL14 in adult dorsal striatal neurons following injection of an AAV expressing either eGFP (fM14;Syn-eGFP) or Cre recombinase (fM14;Syn-Cre) under control of the neuronal promotor synapsin (Syn). Yellow dotted line denotes approximate area of viral expression. B) LC-MS/MS showing reduced levels of m6A mRNA species. Data is normalized to control percent methylated adenosine relative to total adenosine. C) Latency to fall from the accelerating rotarod at 4 and 8 weeks post-injection in individual trials (left) or across whole session (right). N=9 for each group. D) Response learning acquisition (left) and reversal learning (right) in the water-cross maze. Survival graphs show mice reaching criteria for each phase. N=9 for each group. E) Latency to reach a visible platform in the water maze across all 5 trials (top) and for each individual trial (bottom). N=9 for each group. F) Locomotor response to a single injection of D1R agonist SKF82197 (8.0 mg/kg, SKF) across 2 min bins (top). Total ambulatory distance across 60 minutes (bottom, left) and % change in locomotion following SKF81297 injection relative to saline (bottom, right). Syn-eGFP: n=10, Syn-Cre: n=8. G) Locomotor response to a single injection of D2R antagonist eticlopride (0.16mg/kg, etic) across 2 min bins (top). Total ambulatory distance across 60 minutes (bottom, left) and % change in locomotion following eticlopride injection relative to saline (bottom, right). Syn-eGFP: n=9; Syn-Cre n=9. Data shows average across each mouse ± S.E.M. See also Fig. S2.

Analysis of striatal-mediated behaviors showed Syn-cre mice were impaired in sensorimotor learning (Fig. 4C, 4-weeks post-injection: AAV effect: F(1,9)=5.016, p=0.0390; 8-weeks post-injection: F(1,64)=7.639, p=0.0136) as well as both initial acquisition of response learning (Fig. 4D, Log-rank Mantel-Cox, Chi-squared=9.158, p=0.025) and reversal learning (Fig. 4D, Log-rank Mantel-Cox, Chi-squared=14.51, p=0.0001). Strikingly, not a single Syn-Cre mouse completed reversal training. A visible platform test revealed that Syn-Cre mice were overall slower to reach the escape platform (Fig. 4E, F(1,56)=5.227, p=0.0383).

We next assessed the effects of Mettl14 viral deletion on locomotor response to a D1R agonist or D2R antagonist. We found no difference in baseline ambulatory distance (Fig. 4F, F(1,826)=0.6530, p=0.4362; Fig. 4G, F(1,826) =0.05255, p=0.8220). Syn-Cre mice showed a significant increase in locomotor response to the D1R agonist (Fig. 4F virus x drug: F(1,16)=11.54, p=0.000368) and a minor increase in response to the D2R antagonist (Fig. 4G, virus x drug: F(1,14)=3.091, p=0.1010).

DISCUSSION

Brain epitranscriptomics is an emerging concept. Among post-transcriptional modifications, m6A methylation is the most abundant mammalian internal mRNA modification and plays a central role in translational control (Meyer et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2017). Recent studies have implicated m6A-tagging in processes such as the temporal timing of cortical development (Yoon et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018) and the regulation of peripheral axon regeneration (Weng et al., 2018). However, the necessity of m6A-tagging for normal function of neurons in the adult brain has not been definitively demonstrated. Using cell-type-specific or viral-mediated conditional deletion of Mettl14 in the striatum, we show that METTL14 is indispensable for m6A mRNA methylation in the adult mammalian brain and that m6A deficiency profoundly impacts gene expression and impairs striatal-mediated behaviors in adult mice.

In the current study, we focused on the adult striatum for two reasons. First, its functional role in motor learning is well established. Second, there are two prominent and largely discrete neuronal cell types throughout the striatum — striatonigral and striatopallidal — with only a few genes differentiating identity and function. Not too surprisingly, Mettl14 deletion in either subtype led to changes in similar classes of mRNA species. While the fate of m6A-tagged mRNAs (i.e. degradation or increased ribosomal loading) depends on the binding of specific m6A reader proteins (Fu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014a; 2015; Shi et al., 2017), it is remarkable that we observed a clear split in which downregulated mRNAs primarily encoded neuron- and synapse-specific proteins, and upregulated mRNAs primarily encoded globally expressed proteins involved in metabolism and translational regulation. Furthermore, it is intriguing that several mRNAs encoding striatonigral identity genes (e.g. Tac1, Pdyn) were uniquely downregulated following striatonigral Mettl14 deletion, while striatopallidal identity genes (e.g. Penk, Drd2) were uniquely downregulated following striatopallidal Mettl14 deletion. Notably, we found no difference in overall striatal cell numbers or axonal projections in either manipulation, and dendritic morphology was normal following striatonigral Mettl14 deletion. These results suggest that Mettl14, and y extension m6A-tagging, could play an important role in maintaining identity of discrete neuronal populations in adult mice.

The striatum acts to filter cortical inputs, with the striatonigral and striatopallidal pathways working in concert to promote some actions while inhibiting others (Lerner and Kreitzer, 2011). Thus, disruption to either striatonigral or striatopallidal neuron properties (e.g. downreguation of various ion channels) could have profound consequences. Functionally, we found increased neuronal excitability in Mettl14-deficient striatonigral neurons, yet prolonged stimulation impaired spike frequency adaptation. We speculate that such impairment (Venance and Glowinski, 2003; Ha and Cheong, 2017) may profoundly impact the ability of striatonigral neurons to properly integrate cortical inputs and faithfully respond to the increased activity demands that accompany learning. However, whether specific genes contribute to this phenomenon, and whether such a phenomenon translates across other neural subtypes (e.g. glutamatergic projection neurons or interneurons), remain to be determined.

Behaviorally, we observed impaired striatal-dependent behaviors among all three manipulations to varying extents. Mettl14 deletion in D1 neurons resulted in a more severe phenotype than Mettl14 deletion in A2A neurons. This effect may be specific to the affected pathway. Another possible explanation is that D1R, while mostly expressed in striatonigral neurons, is also expressed in some cortical neurons, whereas A2AR expression is more restricted to striatopallidal neurons. Notably, we found the most severe impairments in initial acquisition of response learning and reversal learning following pan-neuronal, viral-mediated Mettl14 deletion in the adult brain, where Mettl14 deletion was most pervasive.

The present study has provided the first direct and specific evidence that m6A deficiency in a subset of neurons in the adult brain impairs learning and performance. Given that activity-dependent protein synthesis in synapses is unique to neurons and central to synaptic plasticity and learning, it is imperative to determine how and if regulation and functional consequences of m6A-tagging in neurons differ from other cells. For example, different m6A reader proteins may mediate specific downstream functional consequences of m6A-tagging following experience-dependent learning. Major challenges remain in determining how m6A and its reader proteins (e.g. YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, or other reader proteins yet to be identified) are dynamically regulated in response to neural activities, and how they in turn influence the spatial and temporal control of protein synthesis to ultimately impact behavior.

STAR METHODS

Contact for reagent and resource sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact: Xiaoxi Zhuang (xzhunag@uchicago.edu).

Experimental models and subject details

General animal information

For all studies, male and female mice aged 2–8 months on a C57BL/J background were used. Mice were housed in standard conditions on a 12 h light/dark cycle in a temperature- and humidity-controlled barrier facility and allowed ad libitum access to standard chow and water. Behavioral testing occurred during the light phase. All procedures were in accordance with guidelines of and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Chicago.

Conditional Mettl14 deletion

Mice with a conditionally removable Mettl14 allele (Yoon et al., 2017; Weng et al., 2018) were crossed to a dopamine 1 receptor (D1R) promoter-driven Cre recombinase transgenic line (B6.FVB(Cg)-Tg(Drd1-cre)EY262Gsat/Mmucd, RRID: MMRRC-030989-UCD) to conditionally delete Mettl14 from striatonigral neurons, or an adenosinse 2A receptor (A2AR) promoter-driven Cre recombinase line (B6.FVB(Cg)-Tg(Adora2a-cre)KG139Gsat/Mmucd, RRID: MMRRC_036158-UCD) to delete Mettl14 from striatopallidal neurons. All experiments performed used double transgenic mice and respective littermate controls. A subset of mice homozygote for the floxed Mettl14 gene (M14f/f) were virally injected with an adeno-associated virus (see below).

Method Details

Viral Injection

Drug and behavior naïve male (~25.0 g) and female (~20.0 g) M14f/f mice aged 8–12 weeks were anesthetized using 2% isofluorane and placed in a stereotaxic frame. Under sterile conditions, the skull of each mouse was exposed and bregma identified. For viral Mettl14 deletion studies, three bilateral bur holes drilled above the dorsal striatum (AP: +1.1 mm, ML: ±1.5 mm; AP: +1.1 mm, ML: ±2.0 mm; AP: +0.5 mm, ML: ±2.0 mm). a guide needle was lowered ~2.7 mm DV into each site relative to the skull surface. 200 nl of an AAV-virus with Cre-recombinase (University of Pennsylvania Vector Core, AAV1.hSyn.Cre.WPRE.hGH,) or eGFP (University of Pennsylvania Vector Core, AAV1.hSyn.eGFP.WPRE.bGH) directed by the synapsin promoter was delivered at a rate of 100 nl/min, and the virus was allowed to diffuse for 7 min post-injection before needle extraction. For mCherry studies (University of North Caroline Vector Core, AAV2-EF1a-DIO-mCherry), the same procedure as above was followed except only one hole bilaterally (AP:0.8, ML: ± 1.7, DV: −2.7) was drilled and only 100 nl of virus was delivered.

Drugs

SKF-82197 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and eticlopride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were used in open field studies. All drugs were dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline, and all injections were intraperitoneal (i.p.) at 0.01 ml/g of body weight.

Rotarod

The accelerating rotarod was used to assess sensorimotor learning as described previously (Beeler et al., 2012; Koranda et al., 2016). Briefly, a computer-controlled rotarod apparatus (Rotamex-5, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA) with a rat rod (7 cm diameter) was set to accelerate from 4 to 40 revolutions per minute (rpm) over 300 s, and time to fall was recorded. Mice received five consecutive trials per session, one session per day with approximately 30 sec intertrial intervals (ITI). All groups of mice received rotarod training at approximately 3 months of age as a high pass filter to verify phenotype.

Visible Platform Test

A white acrylic pool 100 cm diameter (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) was filled so that the water line was approximately 15 cm below the lip of the pool. Water was maintained between 22 and 24 °C. Non-toxic white paint (Reeves and Poole Group, Toronto, Canada) was stirred in and a circular escape platform (diameter 8 cm, Med Associated, St. Albins, VT) was submerged ~0.5 cm below the water surface with a blue flag attached above the water surface. Mice were initially placed on the platform for 15 s. Five subsequent trials were run with the platform moved to a new location at each trial. If the mice did not find the platform within 120 s, the trial was terminated and the mouse was put on the platform for 15 s and then placed under a heat lamp for 30 sec before beginning the next trial. The five trials for each mouse were averaged to yield a single visible platform latency measure and a student’s t-test was performed.

Water Cross Maze

Mice were trained in the water cross maze as described previously (Kheirbek et al., 2008). Briefly, experiments were conducted in the above water tank with white plexiglass walls (University of Chicago, Machine Shop) inserted in the tank to make alleyways. The same escape platform used in the visible platform task was submerged with no visible markers. A black curtain surrounded the maze to reduce spatial cues. A trial was started by placing a mouse in the start arm facing the wall of the tank. Once the mouse made a right or left turn out of the start arm, a divider closed off the arm and the mouse was either allowed to stand on the platform for 15 s or explore the arm of the maze without the platform for 15 s. Mice were then removed from the maze and placed under a heat lamp for 30 seconds before beginning the next trial. Trials were started randomly from either the north or the south end of the maze with the goal arm always to the right of the start arm during initial response acquisition and to the left of the start arm during reversal learning. Correct or incorrect choices were recorded, and the walls of the maze were rotated every ten trials to reduce inter-maze cues. For each phase, criterion was reached once a mouse completed 8 out of 10 trials correctly for 3 consecutive days. For the viral-mediated deletion study, mice that did not reach acquisition criteria by 35 days were removed from the study and 35 days was recorded for statistical purposes. Similarly, for the conditional Mettl14 studies, mice that did not complete reversal in twice the amount of time it took them to complete acquisition were discontinued from the study and records reflected the last day of participating in the experiment. All measurements were made using a live camera and EthoVision (Noldus) software. A log-rank, Mantel-Cox test was used to determine significance.

Open Field

Open field chambers were 40 x 40 cm (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) with lighting at 21 lux. Each chamber was surrounded by black drop cloth obscuring views beyond the chamber. Infrared beams recorded the animals’ locomotor activity. Data were collected in 1 min bins during each session. All drugs were administered immediately prior to mice being placed in the open field.

Immunohistochemistry

Brain tissues were fixed with 4% formaldehyde at various time points post-injection as described in the results and figure legends. Brains were transferred into 30% sucrose for 24 hrs, and then 40 μm coronal serial brain sections were made using a cryostat (Leica Instruments). Prior to immunostaining for METTL14, slices underwent an epitope retrieval protocol where slices were treated for 30 min with a buffer containing 10 μM sodium citrate, pH 9 in tris buffer saline (TBS). This step was skipped for immunohistochemistry not requiring anti-METTL14. Sections were blocked in TBS containing 5% normal donkey serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature, transferred to primary antibody containing 0.3% Triton X-100 with 1% BSA, and incubated at 4 °C for 72 hr. Antibodies used include: mouse monoclonal anti-NeuN (1:250, EDM Millipore Cat# MAB377, RRID: AB_2298772), rabbit polyclonal anti-ENKEPHALIN (ImmunoStar Cat#20065, RRID:AB_572250) and rabbit monoclonal anti-METTL14 (1:200, Sigma-Aldrich Cat# HPA038002, RRID: AB_10672401). Secondary antibodies (Life Technology Invitrogen) were diluted in 5% normal serum at 1:500 for 1 hr at room temperature.

Fluorescent microscopy

Images to confirm Mettl14 deletion in D1R and A2AR cross as well as viral deletion were captured with an Olympus IX81 inverted epiflurorescence microscope with the Olympus Zero Drift Correction auto re-focusing system (Olympus Corporation of the Americas, Center Valley, PA) with a Hamamatsu Orca Flash 4.0 sCMOS camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Skokie, IL) run by Slidebook 5.0 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO). Images were captured at 10x or 60x. Fluorescent intensity and cell counting were performed and analyzed using a minimum of 3 striatal slices from each individual mouse in FIJI (Schindelin et al., 2012).

LC-MS/MS

Levels of total m6A in the striatum were quantified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Striata were dissected out from fresh tissue and total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) using an RNeasy® lipid tissue mini-prep (Qiagen). mRNA was further purified using Dynabeads™ mRNA purification kit and column (Invitrogen). After the addition of NH4HCO3 and alkaline phosphatase and an additional incubation of 2 h at 37 °C, the samples were diluted to 60 μl a nd filtered (Millipore), and 10 μl of each sample was injected into LC-MS/MS. Nucleosides were separated by reverse phase ultra-performance liquid chromatography on a C18 column with on-line mass spectrometry detection using an Agilent 6410 QQQ triple-quadrupole LC mass spectrometer in positive electrospray ionization mode. The nucleosides were quantified by using the nucleoside to base ion mass transitions of 282 to 150 (for m6A), and 268 to 136 (for A). Quantification was performed in comparison with the standard curve obtained from pure nucleoside standards running on the same batch of samples. The ratio of m6A to A was calculated based on the calibrated concentrations, and data was normalized to control samples.

mRNA-seq

PolyA+ RNA was isolated from the striata of 3 mice per group mice as described above. mRNA was further purified using RiboMinus™ Eukaryote Kit v2 (Invitrogen). Around 15 ng purified mRNA from an individual mouse was used for library construction using TruSeq stranded mRNA library prep kit (Illumina) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was carried out on Illumina HiSeq 4000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

m6A-seq

PolyA+ RNA was isolated from mice striata as described above. RNA fragmentation was performed by sonication at 10 ng/ul in 100 ul RNase-free water using Bioruptor Pico (Diagenode) with 30s on/30s off for 30 cycles. m6A-IP and library preparation were performed according to the previous protocol (Dominissini et al., 2013). Specifically, RNA from three mice were pooled together as one replicate. 5 ul 0.5 mg/ml rabbit polyclonal m6A antibody (Synaptic Systems Cat# 202-203, RRID:AB_2279214) and 20 ul Pierce™ protein A (Thermo) were used for each m6A-IP. m6A-modified fragments were eluted with 50 ul 6.6mM m6A nucleotide solution twice, and cleaned up with RNA Clean and Concentrator™-5 (Zymo). Half amount of elute was used for library preparation using TruSeq stranded mRNA library prep kit (Illumina). Sequencing was carried out on Illumina HiSeq 4000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Electrophysiology Slice preparation

Experimenter was bling to genotype. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated into cold oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM): 93 N-methyl-D-glucamine, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 30 NaHCO3, 25 glucose, 12N-acetyl-L-cysteine, 20 HEPES, 5 sodium ascorbate, 2 thiourea, 3 sodium pyruvate, 10 MgSO4(7H2O), and 0.5 CaCl2 (pH 7.3 with HCl). Brains were rapidly removed and 250 μm striatal slices were cut in cold ACSF using a vibratome (Leica VT1000 S). Slices were transferred to 32°C oxygenated ACSF for 12 minutes, then transferred to a perfusion holding chamber with room temperature (20–22°C) oxygenated ACSF containing (in mM): 92 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 30 NaHCO3, 25 glucose, 12 N-acetyl-L-cysteine, 20 HEPES, 5 sodium ascorbate, 2 thiourea, 3 sodium pyruvate, 2 MgSO4(7H2O), and 2 CaCl2 (pH 7.3 with NaOH). Slices were incubated for at least 60 min before recording.

Electrophysiology whole-cell patch clamp recording

Slices were perfused at 2 mL/min at room temperature with oxygenated ACSF containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2(6H2O), 2.5 CaCl2, 20 glucose, 1 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3. All experiments were carried out in the presence of 50 μM picrotoxin. Dorsal striatal MSNs expressing mCherry were identified with epifluorescence microscopy on an upright microscope (Olympus BX51W1). Recordings were made with borosilicate glass patch electrodes (3–7 MΩ) filled with internal solution containing (in mM): 130 K-gluconate, 3 KCl, 0.5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, 3 MgCl2, 4 ATP, 0.3 GTP, and 0.1% w/v biocytin (290 mOsm, pH 7.3 with KOH). Current- and voltage-clamp data were obtained with a MultiClamp 700B amplifier, digitized with a Digidata 1440A digitizer, and viewed with AxonTM pCLAMPTM v10.6.2.2 software (Molecular Devices). Signals were digitized at 10 kHz and filtered at 4 kHz. Holding potential was −80 mV, and series resistance (<25MΩ) was continuous monitored throughout recording with a 10 mV depolarizing step. Experiments were discarded if the series resistance varied by more than 20%. Synaptic currents were evoked by a 200 μs pulse delivered by Master-8 pulse stimulator (A.M.P.I.) through a bipolar tungsten electrode placed within the striatum dorsolateral to the site of recording. Paired-pulse ratio (PPR) was calculated by dividing the second evoked EPSC by the first with a 50-ms inter-stimulus interval. Capacitance was calculated by the pCLAMP 10 software. Input resistance was measured with a −50 pA hyperpolarizing step. Rheobase current, I-V curves, and F-I curves were measured in current clamp by applying 1500 ms current pulses ranging from −200 pA to 400 pA with 25 pA increment steps every 10 seconds. Post recording, lack or presence of METTL14 in biocytin (AnaSpec) filled cells was confirmed.

Dendritic spine morphology

For viral mCherry spine analysis, 250 um sections were submerged in cold formalin over-night and later held in PBS at 4’C. When ready for processing, sections were washed 3 times in PBS for 5 minutes, 3 times in PBS with Triton-X 1% for 5 minutes and an additional 3 times in PBS for 5 minutes. Slices were mounted in Gelvatol medium between two coverslips (Thermo). Imaging and analysis was performed by an analyst blind to the experimental conditions. Second and third order dendrites were imaged with an SP5 Leica confocal under a 63x oil lens with a resolution of .074um x .074um x .130 um. Seven dendrites, one dendrite per neuron, were imaged for each animal.

After acquisition, images were deconvolved using Huygens Professional software using classic maximum likelihood estimations (Scientific Volume Imaging). Images were imported into Imaris 9.0 (Bitplane), a segment 50–75 um away from the soma was cropped to a length of 10um and filtered for artifacts and axons. The Imaris Filament Tracer was used to reconstruct each dendritic segment. The Shortest Distance from Distance Map algorithm was used for dendrite and spine diameter thresholding. Imaris detected potential spines and seed point were inspected and manually adjusted for corrections. Data was exported and finally compiled by a different experimenter.

Sholl analysis

250 μm brain sections containing biocytin filled mCherry expressing D1-MSNs were fixed in formalin and then held in PBS at 4 C. Sections were blocked in TBS containing 5% normal donkey serum, 0.5% Triton-X, and 1% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature, transferred to streptavidin-488 (Invitrogen; Bill’s antibody) in blocking solution, and incubated for 3 hours at room temperature. The biocytin-filled neurons were imaged using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope with a 20x objective and 1.01 μm step size to capture the entire dendritic trees. Image stacks were manually traced and collapsed to 2D images using maximum intensity projection, which were thresholded to create 8-bit binary images in FIJI (Schindelin et al., 2012). Sholl analysis was performed using FIJI (Ferreira et al., 2014). Specifically, 5 μm concentric circles from the center of the cell body were drawn to quantify number of dendritic crossings.

Quantification and data analysis

Behavioral, electrophysiology and morphology experiments

Data are reported as mean ± SEM, and n represents number of mice used per experiment unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was assessed using a student’s t-test or repeated-measures ANOVA for experiments that tracked behavior over time or repeated training, as well as electrophysiology experiments that employed a range to current injections. For the water cross maze studies, a log-rank Mantel-Cox test was employed, due to the fact that several mice were unable to complete all phases of the task. Statistical analysis was performed using R.

High throughput sequencing data general information

All samples were sequenced by Illumina Hiseq 4000 with single end 50-bp read length. The deep sequencing data were mapped to mouse genome (GRCm38/mm10).

m6A-seq

Reads were aligned to the reference genome using Tophat v2.0. The longest isoform was used if the gene had multiple isoforms. Aligned reads were extended to 150bp (average fragments size) and converted from genome-based coordinates to isoform-based coordinates, in order to eliminate the interference from introns in peak calling. The peak calling method was modified from published work (Dominissini, et al., 2013). To call m6A peaks, the longest isoform of each gene was scanned using a 100 bp sliding window with 10 bp step. To reduce bias from potential inaccurate gene structure annotation and the arbitrary usage of the longest isoform, windows with read counts less than 1/20 of the top window in both m6A-IP and input sample were excluded. For each gene, the read counts in each window were normalized by the median count of all windows of that gene. A Fisher exact test was used to identify the differential windows between IP and input samples. The window was called as positive if the FDR < 0.01 and log2(Enrichment fold) ≥1. Overlapping positive windows were merged. The following four numbers were calculated to obtain the enrichment score of each peak (or window): reads count of the IP samples in the current peak/window (a), median read counts of the IP sample in all 100 bp windows on the current mRNA (b), reads count of the input sample in the current peak/window (c), and median read counts of the input sample in all 100 bp windows on the current mRNA (d). The enrichment score of each window was calculated as (a×d)/(b×c).

mRNA-seq

Reads were mapped with Tophat and Cufflink (v2.2.1) was used to calculate the RPKM of each gene to represent their mRNA expression level (Trapnell et al., 2010).

Integrative data analysis and statistics

(1) Fold change (FC) of RNA-seq data: only RPKM no smaller than 1 were kept in further analysis. Triplicates of RNA-seq data (two from replicates of mRNA-seq and one from input of m6A-seq) were used to calculate FC, that is the average RPKM from experimental sample over the average RPKM from control sample. T.test was used to calculate p value between experimental and control group. Only transcripts with p < 0.05 were used for further analysis. (2) m6A peak enrichment fold ratio (control over experimental) is used to represent m6A methylation extent for each transcript. For transcripts with more than one m6A peak, the largest enrichment fold was used. Correlation between m6A methylation extent and RNA expression level was determined using Pearson’s product-moment correlation, and a heat map was generated (Gu et al., 2016). (3) For GO analysis, the list of target genes was first uploaded into DAVID (Huang et al., 2009) and analyzed with functional annotation clustering. The result file was downloaded and extracted with GO terms and corresponding p values.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. m6A enrichment scores and mRNA levels following conditional genetic deletion of Mettl14 in striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons or pan-neuronal viral-mediated deletion in striatum of adult mice. Related to Fig. 1 and Fig. 4.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Mettl14 is required for m6A mRNA methylation in the adult mammalian brain

m6A deficiency in both D1 and D2 striatal neurons downregulates neuronal mRNAs

m6A deficiency in striatal neurons impairs learning and performance

Striatal m6A deficiency alters firing properties without morphological changes

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute of Health- NIGMS R01 GM113194 (H.C.), -NIDA R01DA044997 (X.Z.), NIH Training Grants: T32DA043469 (J.L.K.) and T32MH020065 (W.C.) the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (H.C.) and an equipment grant from the University of Chicago Grossman Institute for Neuroscience, Quantitative Biology and Human Behavior (X.Z). Imaging was performed at the University of Chicago Integrated Light Microscopy Facility. Finally, we would like to thank Jary Delgado and Scott Zhang for technical aid and Dan McGehee for help interpreting the electrophysiological data.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.L.K., C.H. and X.Z. conceived and designed experiments. L.D. developed the conditional mouse line. J.L.K., Y.Y., M.J.P., M.R., L.V., H.S., and K.C. performed the experiments. J.L.K., Z.L., H.S., W.C., performed data analysis and bioinformatics. J.L.K. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpretation of data and final writing of the manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Beeler JA, Frank MJ, McDaid J, Alexander E, Turkson S, Bernandez MS, McGehee DS, Zhuang X. A role for dopamine-mediated learning in the pathophysiology at treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1747–1761. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Salmon-Divon M, Amariglio N, Rechavi G. Transcriptome-wide mapping of N(6)-methyladenosine by m(6)A-seq based on immunocapturing and massively parallel sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:176–89. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira T, Blackman A, Oyrer J, Jayabal A, Chung A, Watt A, Sjöström J, van Meyel D. Neuronal morphometry directly from bitmap images. Nature Methods. 2014;11:982–984. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Eils R, Schlesner M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2847–2849. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha GE, Cheong E. Spike frequency adaptation in neurons of the central nervous system. Exp Neurobiol. 2017;4:179–185. doi: 10.5607/en.2017.26.4.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess ME, Hess S, Meyer KD, Verhagen LA, Koch L, Brönneke HS, Dietrich MO, Jordan SD, Saletore Y, Elemento O, et al. The fat mass and obesity associated gene (Fto) regulates activity of the dopaminergic midbrain circuitry. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1042–1048. doi: 10.1038/nn.3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DW, Lempicki RA, Sherman BT. Systemic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G, Yang S, Jian X, Yi C, Zhou Z, He C. Oxidative demethylation of 3-methylthymine and 3-methyluracil in single-stranded DNA and RNA by mouse and human FTO. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3313–3319. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y, Yi C, Lindahl T, Pan T, Yang YG, et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;8:885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheirbek MA, Britt JP, Beeler JA, Ishikawa Y, McGehee DS, Zhuang X. Adenylyl cyclase type 5 contributes to corticostriatal plasticity and striatum-dependent learning. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12115–12124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3343-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koranda JL, Krok AC, Xu J, Contractor A, McGehee DS, Beeler JA, Zhunag X. J Neurosci. 2016;36:5228–5240. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2754-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner TN, Kreitzer AC. Neuromodulatory control of striatal plasticity and behavior. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JZ, Yue Y, Han D, Wang X, Fu Y, Zhang L, Jia G, Yu M, Lu Z, Deng X, et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adeosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:93–95. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauer J, Luo X, Blanjoe A, Jiao X, Grozhik AV, Patil DP, Linder B, Pickering BF, Vasseur JJ, Chen Q, Gross SS, Elemento O, Debart F, Kiledjian M, Jaffrey SR. Reversible methylation of m6Am in the 5’ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature. 2017;541:371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature21022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, Elemento O, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3’ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012;149:1635–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:313–326. doi: 10.1038/nrm3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Wang X, Lu Z, Zhao BS, Ma H, Hsu PJ, Liu C, He C. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N6-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res. 2017;27:315–328. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillivan SE, Konradi C. Expression and function of dopamine receptors in the developing medial frontal cortex and striatum of the rat. Neurosci. 2011;199:501–514. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Patcher L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venance L, Glowinski J. Heterogeneity of spike frequency adaptation among medium spiny neurons from the rat striatum. Neuroscience. 2003;122:77–92. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, Hon GC, Yue Y, Han D, Fu Y, Parisien M, Dai Q, Jia G, et al. N6-methyladenosie-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2104a;505:117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, Lu Z, Han D, Ma H, Weng X, Chen K, Shi H, He C. N(6)-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell. 2015;161:1388–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li Y, Yue M, Wang J, Kumar S, Wechsler-Reya RJ, Zhang Z, Ogawa Y, Kellis M, Duester G, Zhao JC. N6-methyladenosine RNA modification regulates embryonic neural stem cell self-renewal through histone modifications. Nat Neurosci. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0057-1. Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver D. A2a adenosine receptor expression in the developing rat brain. Mol Brain Res. 1993;20:313–327. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90058-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng Y, Wang X, An R, Cassin J, Vissers C, Liu Y, Liu Y, Xu T, Wang X, Wong SZH, et al. Epitransctriptomic m6A regulation of axon regeneration in the adult mammalian nervous system. Neuron. 2018;97:313–325. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widagdo J, Zhao QY, Kempen MJ, Tan MC, Ratnu VS, Wei W, Leighton L, Spardaro PA, Edson J, Anggono V, et al. Experience-dependent accumulation of N6-methyladenosine in the prefrontal cortex is associated with memory processes in mice. J Neurosci. 2016;36:6771–6777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4053-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon KJ, Ringeling FR, Vissers C, Jacob F, Pokrass M, Jimenez-Cyrus D, Su Y, Kim NS, Zhu Y, Zheng L, Kim S, Wang X, Doré LC, Jin P, Regot S, Zhuang X, Canzar S, He C, Ming GL, Song H. Temporal control of mammalian cortical neurogenesis by m6A methylation. Cell. 2017;171:877–889. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, He C. Post-transcriptional gene regulation m6 mRNA modifications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:31–42. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, Vågbø CB, Shi Y, Wang WL, Song SH, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. m6A enrichment scores and mRNA levels following conditional genetic deletion of Mettl14 in striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons or pan-neuronal viral-mediated deletion in striatum of adult mice. Related to Fig. 1 and Fig. 4.