Abstract

Stachys pilifera (S. pilifera) Benth (Lamiaceae) is used in traditional medicine to treat a variety of diseases. Despite some reports on the antitumor effects of some species of this genus, anticancer activity of S. pilifera has not been yet reported. Here, we examined the cytotoxic effect and cell death mechanisms of methanolic extract of S. pilifera and its alkaloid and terpenoid fractions on the HT-29 colorectal cell line. HT-29 cells were cultivated and then incubated in the methanolic extract of S. pilifera and its fractions at various concentrations for 24 h. Cell viability was measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Morphology of cells was evaluated by contrast microscopy. Furthermore, effects of the tested extract and fractions were tested on some regulators of cell death and proliferation such as caspase-8, caspase-9, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), and nitric oxide (NO). Cisplatin was used as positive control. The estimated IC50 values of the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions, and cisplatin against HT29 cell after 24 h were determined to be 612, 48.12, 46.44, and 4.02 μg/mL, respectively. Morphological changes such as plasma membrane blebbing, cell size reduction, and apoptotic bodies were observed in cells faced with the extract and fractions. S. pilifera extract and its fractions induced apoptosis through inhibition of NF-κB, NO, and activation of caspase-8 and caspase-9. Data showed considerable cytotoxic and antiproliferative effects of S. plifera on colorectal cell line through induction of apoptosis. These findings provide a basis for the therapeutic potential of S. pilfera in the treatment of colon cancer.

Keywords: Apoptosis, HT29, NF-κB, Nitric oxide, Stachys pilifera

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is a complicated disease not curable in most cases and remains as a major leading cause of death all around the world(1). Colorectal cancer is considered as the third reason of cancer death in Iran. It is also the third leading reason of death in men after lung and prostate cancer tumors and in women after lung and breast cancers, respectively(2). Potential risk factors for the growth of colorectal cancer include lack of physical activity, alcohol consumption, smoking, a low-fiber and high-fat nutrition, obesity, and inadequate fruit and vegetable usage(3). Nowadays, there is no definite treatment for colorectal cancer; hence, an effective and safe treatment for colorectal cancer is urgently required.

The usage of medicinal herbs is always considered as an effective approach to control various diseases such as pain, inflammation, and cancers. Currently, many studies are being concentrated on natural compounds obtained from medicinal plants for suppression of growth or progression tumor.

Stachys (Lamiaceae) is a large genus, including about 300 species that widely spreads in tropical and subtropical regions(4). This genus is represented by 34 species in Iran of which13 are endemic(5,6). The presence of flavonoids, phenylethanoid glycosides, diterpenes, saponins, terpenoids, and steroids have been reported in Stachys species(7,8).

By phytochemical screening, the main classes of secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, iridoids, fatty acids, and phenolic acids have been isolated from various parts of the genus Stachys (9). Previous studies have revealed considerable anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial, and hepatoprotective properties of this genus. Furthermore, it has been identified that the essential oils and extracts of different Stachys species generate considerable cytotoxic and antitumor effects in vitro (10,11,12).

Stachys pilifera (S. pilifera) Benth is one of the endemic species in Iran. The aerial parts of this plant are utilized in Iranian traditional medicine for the treatment of various disorders such as asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and infections(13). A biological in vitro study showed the potent antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antitumor activities of the n-butanolic extract of S. pilifera (9). It has also been revealed that the hydroalcoholic extract of S. pilifera is an effective natural substance to suppress inflammation in various animal models. Sadeghi et al., identified the hepatoprotective effect of S. pilifera Benth on CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity in rats(14).

The cytotoxic effects of some Stachys species on A431, HeLa, and MCF-7 have been evaluated(15). It was reported that Stachys recta and Stachys palustris stem extracts significantly prevented the proliferation of HeLa cells. Furthermore, Khanavi et al., showed that Stachys laxa exhibits significant cytotoxicity on T47D and HT-29 cell lines(16).

To the best of our knowledge, thus far, the possible effects of S. pilifera on colorectal cancer cell linehas not been reported. Therefore, the aim of this work was to investigate the cytotoxic and apoptogenic activates of methanol extract, alkaloid, and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera against HT-29 human colorectal cancer cell line.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Cell culture medium (Dulbecco's modified eagle's medium (DMEM)), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, streptomycin, and trypsin-EDTA were purchased from Gibco BRL (Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland). 3- (4,5- dimethylthiazol -2- yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), ethanol, Griess reagent, and Triton X-100 were procured from Sigma-Aldrich Corp (St. Louis, MO, USA). Caspase-8 and caspase-9 activity assay kits were purchased from Biovision (Inc., USA). NF-κB p65 ELISA assay kits were supplied by Abcam, USA. Cisplatin was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Plant material

Stachys pilifera Benth was collected in spring 2017 from Kakan, Yasuj, I.R. Iran. The plant was identified by Dr. A. Jafari from Department of Botany, Center for Research in Natural Resource and Animal Husbandry, Yasuj University, Yasuj, I.R. Iran where a voucher specimen of the plant (herbarium No. 1897) was deposited. The aerial part of plant materials were cleaned and shade dried and then powdered. The powder was kept in a closed container at 4 °C.

Extract preparation

Dried leaf powder of the plant (200 g) was extracted three times with MeOH-H2O (70:30) at room temperature by maceration method for three days and then, the extract was filtered and evaporated using rotary evaporator to obtain 16.42 g of the methanolic extract. The residue was kept in the refrigerator for the assessment of cytotoxic activity(17). A part of the MeOH extract was consequently partitioned with petroleum ether. The methanolic phase was acidified with 2 N HCl (pH = 2.0)(18) and then, the pH of acidic solution was adjusted to 8-9 with 25% NH3 and re-extracted with chloroform (3 × 100 mL). The chloroform phase was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated to obtain 1.94 g of S. pilifera alkaloid fraction. The terpenoid fraction was prepared based on a method presented by Kumar et al.(19). Briefly, the powdered samples were twice extracted with n-hexane for 48 h at room temperature by maceration. After filtration, the n-hexane extract was diluted with methanol and maintained at -20 °C for 24 h. Afterward, methanolic phase was separated and evaporated using rotary evaporator to obtain terpenoid fraction.

Cell culture

The human colon adenocarcinoma (HT-29) cell line was obtained from Pasteur Institute of Iran (Tehran, I.R. Iran). The cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere (90%) containing 5% CO2 and then, cultured in DMEM with 10% (v/v) FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cells were seeded overnight and then, incubated with different concentrations of the methanolic extract, cisplatin, terpenoid or alkaloid fractions.

Cell viability

The cell viability was determined using a modified MTT assay(19). In brief, the cells (1 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates and exposed to the indicated concentration of the extract, fractions, and cisplatin for 24 h. The samples including methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions, and cisplatin were tested at 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800 μg/mL concentrations. The samples were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and further diluted with cell culture medium. The final concentration of DMSO was adjusted to 1% of total volume of the medium in all treatment, including the blank. A control medium without DMSO was also incubated. After the treatment, 5 mg/mL of MTT solution were added and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C in a dark place. The absorbance of formazan creation was measured at a wavelength of 540 nm with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The cell viability by MTT assay was calculated as a percentage of the control value (untreated cells)(20).

Morphological study

The HT-29 cells were cultured overnight at a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL on the sterile culture plates and then treated with methanolic extract, terpenoid and alkaloid fractions, and cisplatin at concentrations equal to 75% of the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 incubator. The untreated cells in 1% DMSO were used as a negative control. The changes in cellular morphology were observed using phase contrast microscopy at ×10 magnification (Olympus, Japan)(21).

Assessment of caspase-8 and caspase-9 activities

To examine caspase-8 and caspase-9 activities, the colorimetric protease assay kits were used which uses synthetic tetrapeptides Ile-Glu-Thr-Asp (IETD) for caspase-8 and Leu-Glu-His-Asp (LEHD) for caspase-9 labeled with p-nitroaniline (pNA). Briefly, 3 × 106 cells/well were aliquoted into 96-well plates and permitted to adhere overnight. Cells were then treated as indicated and pelleted after 24 h to include any floating cells. The supernatants were removed and the cell pellets were lysed and assayed according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 2 h incubation with IETD-pNA or LEHD-pNA substrates, the pNA light emission was quantified using a microtiter plate reader at 405 nm. The comparison of the absorbance of pNA from the apoptotic sample with un-induced control determined the fold increase in caspase activity(22,23).

Assessment of nuclear factor-κB p65

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) p65 ELISA assay kits were used to determine NF-κB p65. After the treatment of HT-29 cancer cells with lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (10 μg/mL for 6 h), they were lysed with hypotonic HEPES lysis buffer and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. Then, supernatants were used for the determination of NF-κB. To sum up, a specific double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) sequence containing the NF-κB response element was immobilized onto the bottom of wells of a 96-well plate. NF-κB contained in a nuclear extract binds specifically to the NF-κB response elements. NF-κB p65 was detected by the addition of specific primary antibody directed against NF-κB p65. A secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was added and the absorbance was read at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer(24).

Assessment of nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (NO) generation was evaluated by determining the stable end-product nitrite in the cell culture supernatants by the fluorometric assay, which is based on the reaction of nitrite with 2, 3-diaminonaphthalene to form the fluorescent product 1-(H)-naphthotriazole. Then, nitrite generation was determined by adding 0.1 mL of cell culture medium to 0.1 mL of Griess reagent in a 96-well plate. After 15 min incubation at 37 °C in a dark place, the absorbance was read at 540 nm with a Packard EL 340 microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). For each experimental condition, a blank sample was prepared in the absence of the cells, and its absorbance was subtracted from that measured in the presence of the cells(25).

Statistical analysis

The data are reported as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses of the results were performed using one-way ANOVA (Graph Pad Prism 6 for windows) followed by Tukey's post hoc test, and the level of P < 0.05 was considered significant between the treated and untreated groups.

RESULTS

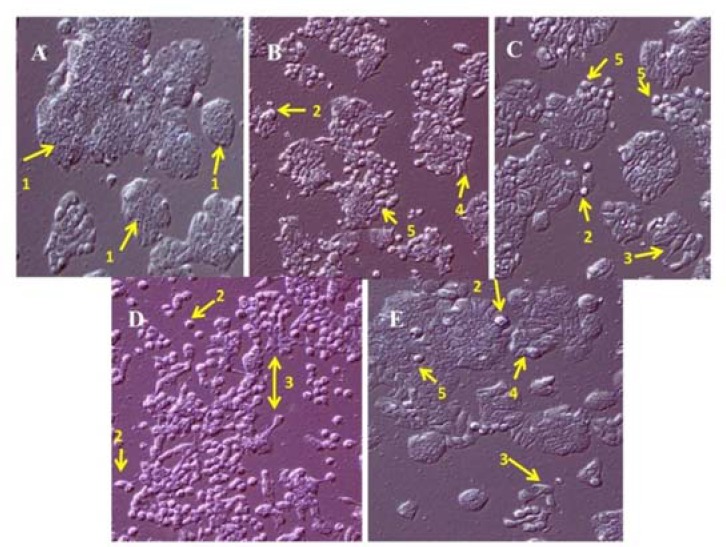

Cell viability

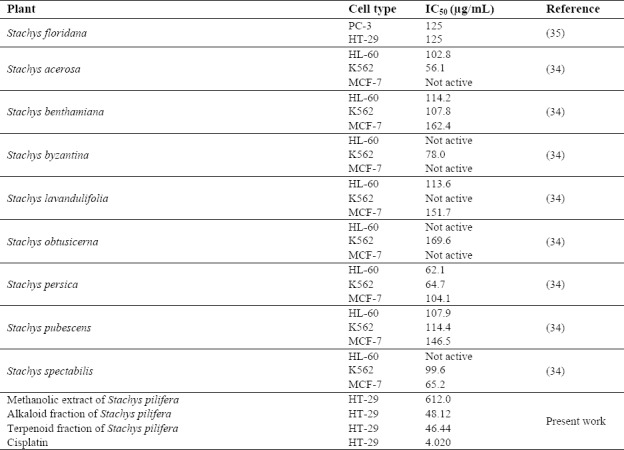

The HT-29 cells were treated with different concentration of the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera and cisplatin for 24 h. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. The doses of the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera and cisplatin inducing IC50 of HT-29 human colorectal cell are presented in Table 1. The IC50 of cisplatin, as the positive control, under all identical conditions, was nearly 4.02 μg/mL. In comparison to the methanolic extract having IC50 of 612 μg/mL, the results of alkaloid and terpenoid fractions showed favorable inhibitory properties in lower concentrations of 48.12 and 46.44 μg/mL, respectively.

Table 1.

The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of Stachys pilifera and cisplatin against HT-29 cell line.

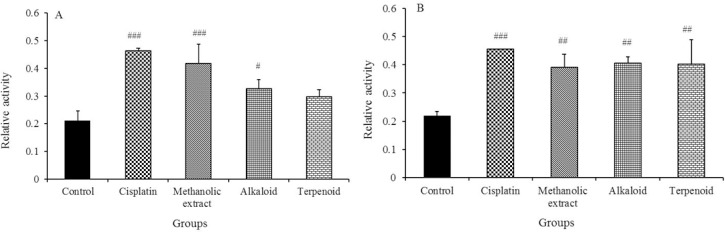

Effect of the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera and cisplatin on the morphology of HT-29 cell line

The cellular morphology of HT-29 cell line was visualized using phase contrast microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1, the treatment of cells with methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions induces the significant cellular morphological changes like apoptotic bodies, cell debris, cell shrinkage, and detached cells. The morphological changes induced with alkaloid fraction, to some extent, were similar to that observed with cisplatin.

Fig. 1.

Morphology of HT-29 cell line by phase contrast microscopy at ×10. (A) untreated, (B) treated with concentration less than IC50 (75% of IC50) of methanolic extract of Stachys plifera, (C) alkaloid fraction, (D) terpenoid fraction, and (E) cisplatin after 24 h. The arrows indicate (1) normal cell, (2) apoptotic bodies, (3) cell debris, (4) cell shrinkage, and (5) detached cells.

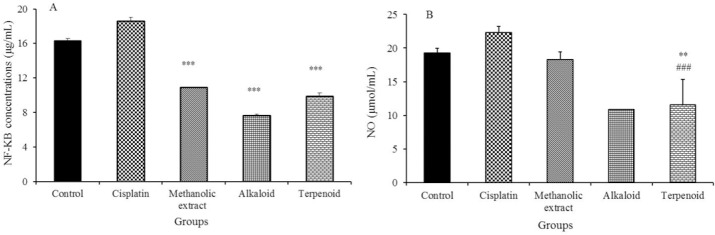

Effect of the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera and cisplatin on the activity of caspase-8 and caspase-9 in HT-29 cell line

As illustrated in Figs. 2A and 2B, the activity of caspase-8 and caspase-9 significantly were increased with the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera. Caspase 8 activity was increased respectively by 99, 55.2, and 41.42 % once cells were exposed to methanolic extract, alkaloid or terpenoid fractions, whereas caspase 9 activation was increased by 78.53, 85.38, and 83.56 % .

Fig. 2.

Effect of the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of Stachys pilifera and cisplatin on the activity of (A) caspase-8 and (B) caspase-9 in the HT-29 cell line. Values are expressed as means ± SD of 3 experiments. # Significantly different from cisplatin. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001.

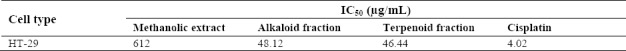

Effect of the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera and cisplatin on the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) p65

As shown in Fig. 3A, HT-29 cancer cell line treated with the methanolic extract, line treated with the methanolic extract, alkaloid or terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera showed a significant decrease in NF-κB p65 levels as compared with the untreated cells. The results indicate that NF-κB p65 level is not decreased by cisplatin as compared with untreated cells.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the methanolic extract, terpenoid and alkaloid fractions of Stachys pilifera on (A) nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and (B) nitric oxide (NO) concentration. Values are expressed as means ± SD of 3 experiments. Statistically significant differences are given compared to the control group (**P < 0.01) and cisplatin (#P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001).

Effect of the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera and cisplatin on the concentration of nitric oxide

As indicated in Fig. 3B, HT-29 cancer cell line treated with the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fraction of S. pilifera led to a significant decrease in NO concentration as compared with the untreated cells. Nitric oxide level is not decreased by cisplatin as compared with the untreated cells.

DISCUSSION

Natural products have long been utilized to inhibit and treat diseases such as pain, inflammation, and cancers. Previous findings have indicated that medicinal plants can be used as good candidates for the expansion of new anti-cancer agents(26). In the present work, the cytotoxic and apoptogenic effects of the methanolic extract, alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera were evaluated against HT-29 colorectal cell line. The results revealed that the methanolic extract of S. pilifera and its alkaloid and terpenoid fractions led to significant cytotoxic activities on HT-29 cell line. The MTT assay results indicated that the alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera have greater cytotoxic effects than the methanolic extract.

Cytotoxic effects of medicinal plant extracts can be intermediated through the initiation of apoptosis(27). Programmed cell death (apoptosis) happens in physiological and pathological situations and is characterized by morphological changes such as cell shrinkage, apoptotic bodies, cell debris, and detached cells(28,29). The results of the present study revealed that the methanolic extract of S. pilifera and its fractions induce the mentioned morphological changes. These changes could be an indicator of the occurrence of apoptosis in the treated cells.

It is important to mention that medicinal plants have different effects on cancer cell lines. Mechanistic elucidation of these effects is a fundamental aspect for researchers. Likewise, it has been identified that herbal medicine could mediate their effects throuh different pathways for modulation of proliferation and metastasis cancer cells. In the present study, several possible pathways were examined to investigate the cytotoxic effect of S. pilifera on HT-29 cell line.

Caspases, a group of cysteine proteases, are identified as primary controllers of apoptotic cell death. These enzymes are involved in the induction and execution phase of apoptosis by cleaving more than 400 substrates(29). The data demonstrated that treatment with the extracts induces activation of caspase-8 and caspase-9. Therefore, it could be suggested that one plausible mechanism of apoptosis induction by S. pilifera is through the activation of caspase-8 and caspase-9, i.e. extrinsic and intrinsic pathways.

Nitric oxide, a transient endogenously made gas, is generated by a complex group of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) enzymes. Nitric oxide has been reported to modulate diverse cancer-related events(2). There is some evidence to indicate that up-regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and nitrite production involve in the activation of NF-κB(3) and subsequent binding of the κB enhancer components in the iNOS gene promoter. Accordingly, targeting NF-κB could be important in suppression of tumor cells growth and their metastasis, and its expression has a good correlation with NO levels(30,31). The present results clarified that treated HT-29 cancer cell line with the methanolic extract and two fractions of S. pilifera decreased NF-κB and subsequently NO level.

Finally, it is important to mention that both alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera showed a significant anti-proliferative effects against HT-29 cell line. Thus, it could be suggested that cytotoxic effects of S. pilifera are not just related to one specific chemical agent, and it may be due to the combination of its materialistic existence and structural integrity, providing such positive anticancer results.

It has been reported that essential oils(32) and extracts of various Stachys species produce significant cytotoxic effects in vitro. Cytotoxicity of different extracts of Stachys species in human cancer cell lines reported in the literature are given in Table 2 for the sake of comparison with the toxicity of S. pilifera . It can be concluded from Table 2 that the alkaloid and terpenoid fractions of S. pilifera have a lower IC50 and a higher efficiency than those observed with the extracts of Stachys species in human cancer cell lines(33,34,35).

Table 2.

Comparison of cytotoxicity of Stachys pilifera with other Stachys species in human cancer cell lines reported in the literature.

Previous studies have demonstrated the presence of aucubin and harpagide (iridoid glycosides) in Stachys plants and have stated that these compounds are probably responsible for the cytotoxic effects observed for these plants(36). Other investigators have suggested that sesquiterpene compounds and carvacrol may be responsible for the cytotoxic activity of various Stachys species(32).

The presence of cytotoxic compounds with various polarities in different Stachys species observed by other investigators is in accordance with our observations that the alkaloid (48.12 μg/mL) and terpenoid (46.44 μg/mL) fractions of S. pilifera (that may contain more nonpolar compounds such as alkaloids and terpenoids) showed higher cytotoxic effects than its methanolic extract (that contains more polar agents such as phenolic compounds) (612.0 μg/mL).

CONCLUSION

The data confirmed the considerable cytotoxic and anti-proliferative properties of the methanolic extract of S. pilifera and its alkaloid and terpenoid fractions on HT-29 human colorectal cancer cell line through the induction of apoptosis pathways. These findings provide a good basis for the therapeutic potential of S. pilifera in the treatment of colorectal cancer. The isolation and identification of the compound that are responsible for these effects may lead to the development of a new anticancer compound against colorectal cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was financially and technically supported (Grant No. 1394.144) by Medicinal Plants Research Center of University of Guilan, Rasht, I.R. Iran and Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, I.R. Iran.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74(11):2913–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmedin Jemal DA, Tiwari RC, Murray T, Ghafoor A, Samuels A, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics. 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(1):8–29. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogan FS, Krishnegowda NK, Mikhailova M, Kahlenberg MS. Flavonoid, silibinin, inhibits proliferation and promotes cell-cycle arrest of human colon cancer. J Surg Res. 2007;143(1):58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar D, Bhat ZA, Kumar V, Khan NA, Chashoo IA, Zargar MI, et al. Effects of Stachys tibetica essential oil in anxiety. Eur J Integr Med. 2012;4(2):e169–e176. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salmaki Y, Zarre S, Govaerts R, Bräuchler C. A taxonomic revision of the genus Stachys (Lamiaceae: Lamioideae) in Iran. Bot J Linn Soc. 2012;170(4):573–617. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salmaki Y, Zarre S, Lindqvist C, Heubl G, Bräuchler C. Comparative leaf anatomy of Stachys (Lamiaceae: Lamioideae) in Iran with a discussion on its subgeneric classification. Plant Syst Evol. 2011;294(1-2):109–125. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Javidnia K, Miri R, Moein MR, Kamalinejad M, Sarkarzadeh H. Constituents of the essential oil of Stachys pilifera Benth. from Iran. J Essent Oil Res. 2006;18(3):275–277. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biglar M, Ardekani MR, Khanavi M, Shafiee A, Rustaiyan A, Salimpour F, et al. Comparison of the volatile composition of Stachys pubescence oils obtained by hydro distillation and steam distillation. Pak J Biol Sci. 2014;17(7):942–946. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2014.942.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farjam MH, Khalili M, Rustayian A, Javidnia K, Izadi S. Biological activity of the n-butanolic extract of Stachys pilifera. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5(28):5115–5119. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hajhashemi V, Ghannadi A, Sedighifar S. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of the hydroalcoholic, polyphenolic and boiled extracts of Stachys lavandulifolia. Res Pharm Sci. 2007;1(2):92–98. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonboli A, Salehi P, Ebrahimi SN. Essential oil composition and antibacterial activity of the leaves of Stachys schtschegleevii from Iran. Chem Nat Compd. 2005;41(2):171–174. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khanavi M, Sharifzadeh M, Hadjiakhoondi A, Shafiee A. Phytochemical investigation and anti-inflammatory activity of aerial parts of Stachys byzanthina C. Koch. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97(3):463–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadeghi H, Zarezade V, Sadeghi H, Toori MA, Barmak MJ, Azizi A, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of Stachys pilifera Benth. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(9):e19259–e19266. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.19259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panahi Kokhdan E, Ahmadi K, Sadeghi H, Sadeghi H, Dadgary F, Danaei N, Aghamaali MR. Hepatoprotective effect of Stachys pilifera ethanol extract in carbon tetrachloride-induce hepatotoxicity in rats. Pharm. Biol. 2017;55(1):1389–1393. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2017.1302484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khanavi M, Manayi A, Lotfi M, Abbasi R, Majdzadeh M, Ostad SN. Investigation of cytotoxic activity in four Stachys species from Iran. Iran J Pharm Res. 2012;11(2):589–593. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khanavi M, Nabavi M, Sadati N, Shams Ardekani M, Sohrabipour J, Nabavi SM, et al. Cytotoxic activity of some marine brown algae against cancer cell lines. Biological Res. 2010;43(1):31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordanian B, Behbahani M, Carapetian J, Fazilati M. In vitro evaluation of cytotoxic activity of flower, leaf, stem and root extracts of five Artemisia species. Res Pharm Sci. 2014;9(2):91–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadjiakhoondi F, Ostad SN, Khanavi M, Hadjiakhoondi A, Farahanikia B, Salarytabar A. Cytotoxicity of two species of Glaucium from Iran. J Med Plant. 2013;1(45):85–92. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S, Mishra A, Pandey AK. Antioxidant mediated protective effect of Parthenium hysterophorus against oxidative damage using in vitro models. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13(1):120–128. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadeghi H, Yazdanparast R. Effect of Dendrostellera lessertii on the intracellular alkaline phosphatase activity of four human cancer cell lines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;86(1):11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00380-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suhaimi SA, Hong SL, Malek SN. Rutamarin, an active constituent from Ruta angustifolia Pers., induced apoptotic cell death in the HT29 colon adenocarcinoma cell line. Pharmacogn Mag. 2017;13(Suppl 2):S179–S188. doi: 10.4103/pm.pm_432_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright K, Kolios G, Westwick J, Ward SG. Cytokine-induced apoptosis in epithelial HT-29 cells is independent of nitric oxide formation evidence for an interleukin-13-driven phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent survival mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(24):17193–17201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo YJ, Yang JS, Lu CC, Chiang Sy, Lin JG, Chung JG. Ethanol extract of Hedyotis diffusa willd upregulates G0/G1 phase arrest and induces apoptosis in human leukemia cells by modulating caspase cascade signaling and altering associated genes expression was assayed by cDNA microarray. Environ Toxicol. 2015;30(10):1162–1177. doi: 10.1002/tox.21989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park MH, Hong JE, Park ES, Yoon HS, Seo DW, Hyun BK, et al. Anticancer effect of tectochrysin in colon cancer cell via suppression of NF-kappaB activity and enhancement of death receptor expression. Mol Cancer. 2015;14(1):124–135. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0377-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopecka J, Campia I, Brusa D, Doublier S, Matera L, Ghigo D, et al. Nitric oxide and P‐glycoprotein modulate the phagocytosis of colon cancer cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(7):1492–1504. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song Y, Manson JE, Buring JE, Sesso HD, Liu S. Associations of dietary flavonoids with risk of type 2 diabetes, and markers of insulin resistance and systemic inflammation in women: a prospective study and cross-sectional analysis. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24(5):376–384. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2005.10719488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aghbali A, Hosseini SV, Delazar A, Gharavi NK, Shahneh FZ, Orangi M, et al. Induction of apoptosis by grape seed extract (Vitis vinifera) in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2013;13(3):186–191. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2013.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vitalone A, Guizzetti M, Costa LG, Tita B. Extracts of various species of Epilobium inhibit proliferation of human prostate cells. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2003;55(5):683–690. doi: 10.1211/002235703765344603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiss A, Kowalski J, Melzig MF. Induction of neutral endopeptidase activity in PC-3 cells by an aqueous extract of Epilobium angustifolium L. and oenothein B. Phytomedicine. 2006;13(4):284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baek S-H, Kwon TK, Lim JH, Lee Y-J, Chang H-W, Lee S-J, Kim J-H, Kwun K-B. Secretory phospholipase A2-potentiated inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by macrophages requires NF-κB activation. J Immunol. 2000;164(12):6359–6365. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prabhu KS, Zamamiri-Davis F, Stewart JB, Thompson JT, Sordillo LM, Reddy CC. Selenium deficiency increases the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in RAW 264.7 macrophages: role of nuclear factor-κB in up-regulation. Biochem J. 2002;366(Pt 1):203–209. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conforti F, Menichini F, Formisano C, Rigano D, Senatore F, Arnold NA, et al. Comparative chemical composition, free radical-scavenging and cytotoxic properties of essential oils of six Stachys species from different regions of the Mediterranean Area. Food Chem. 2009;116(4):898–905. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serbetci T, Demirci B, Güzel CB, Kültür S, Ergüven M, Başer KH. Essential oil composition, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of two endemic Stachys cretica subspecies (Lamiaceae) from Turkey. Nat Prod Commun. 2010;5(9):1369–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jassbi AR, Miri R, Asadollahi M, Javanmardi N, Firuzi O. Cytotoxic, antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of nine species of woundwort (Stachys) plants. Pharm Biol. 2014;52(1):62–67. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2013.810650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma L, Qin C, Wang M, Gan D, Cao L, Ye H, et al. Preparation, preliminary characterization and inhibitory effect on human colon cancer HT-29 cells of an acidic polysaccharide fraction from Stachys floridana Schuttl. ex Benth. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;60:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haznagy-Radnai E, Rethy B, Czigle S, Zupko I, Weber E, Martinek T, et al. Cytotoxic activities of Stachys species. Fitoterapia. 2008;79(7-8):595–597. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]