Abstract

Background

Maternal infection is a risk factor for periventricular leukomalacia and cerebral palsy (CP) in neonates. We have previously demonstrated hypomyelination and motor deficits in newborn rabbits, as seen in patients with cerebral palsy, following maternal intrauterine endotoxin administration. This was associated with increased microglial activation, primarily involving the periventricular region (PVR). In this study we hypothesized that maternal intrauterine inflammation leads to a pro-inflammatory environment in the PVR that is associated with microglial activation in the first 2 postnatal weeks.

Methods

Timed pregnant New Zealand white rabbits underwent laparotomy on gestational day 28 (G28). They were randomly divided to receive lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 20 μg/kg in 1 mL saline) (Endotoxin group) or saline (1 mL) (control saline, CS group), administrated along the wall of the uterus. The PVR from the CS and Endotoxin kits were harvested at G29 (1 day post-injury), postnatal day1 (PND1, 3 day post-injury) and PND5 (7 days post-injury) for real-time PCR, ELISA and immunohistochemistry. Kits from CS and Endotoxin groups underwent longitudinal MicroPET imaging, with [11C]PK11195, a tracer for microglial activation.

Results

We found that intrauterine endotoxin exposure resulted in pro-inflammatory microglial activation in the PVR of rabbits in the first postnatal week. This was evidenced by increased TSPO (translocator protein) expression co-localized with microglia/macrophages in the PVR, and changes in the microglial morphology (ameboid soma and retracted processes). In addition, CD11b level significantly increased with a concomitant decline in the CD45 level in the PVR at G29 and PND1. There was a significant elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and iNOS, and decreased anti-inflammatory markers in the Endotoxin kits at G29, PND1 and PND5. Increased [11C]PK11195 binding to the TSPO measured in vivo by PET imaging in the brain of Endotoxin kits was present up to PND14–17.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that a robust pro-inflammatory microglial phenotype/brain milieu commenced within 24 h after LPS exposure and persisted through PND5 and in vivo TSPO binding was found at PND14–17. This suggests that there may be a window of opportunity to treat after birth. Therapies aimed at inducing an anti-inflammatory phenotype in microglia might promote recovery in maternal inflammation induced neonatal brain injury.

Keywords: cerebral palsy, maternal inflammation, microglia, cytokines, neonatal brain injury, periventricular leukomalacia, rabbits

Introduction

Inflammation induced by in utero or perinatal infection, or triggered by a variety of causes (including ischemic insults) is implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders such as cerebral palsy (CP) and autism spectrum disorders [1–4]. Clinical studies have shed light on the role of maternal infection (chorioamnionitis) in the subsequent development of cystic periventricular leukomalacia and CP [5–7]. Chorioamnionitis confers a four-fold increased risk of CP in term infants [8]. The presence of inflammatory markers in the serum has been associated with a higher risk for delayed motor development and cognitive impairment in preterm infants [9].

In order to characterize the effect of maternal inflammation on fetal and postnatal brain, we have employed a rabbit model of CP produced by injecting LPS along the uterus at near-term (G28). Rabbit kits exposed to this treatment show motor deficits, such as hind limb spasticity, poor righting reflex, decreased movements and decreased coordination in sucking and swallowing [10]. In addition, there was hypomyelination and intense microglial activation in the white matter regions at PND1 measured in vitro with immunocytochemistry, and microglial activation imaged in vivo with PET by showing increased [11C]PK11195 binding to the mitochondrial TSPO [11, 12]. Thus, near-term LPS exposure in rabbit kits models clinical and neuropathological manifestations seen in patients with CP.

Microglia are resident immune cells in the healthy brain [13, 14] and are present in large numbers in the white matter tracts during development [15, 16]. Microglia are rapidly activated and undergo dramatic morphological and phenotypic changes after acute brain injury [17–19]. Activated microglia and recruited macrophages can promote both neurotoxicity through the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species [20, 21], and neuroprotection through the removal of cell debris [22] and production of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF [23, 24]. Studies have assessed the effects of microglial activation as a response to infection, inflammatory challenge, hypoxia–ischemia and excitotoxic insults in different species (sheep, rabbit, rat, mouse, piglet and guinea pig) during various stages of pregnancy and neonatal life (reviewed by [25–27]). Several studies have consistently shown that increased density of microglia and macrophages are related to white matter damage and deficits in myelination in the immature brain [28–35]. The predominant microglial phenotype clearly depends on the type of injury, location (grey versus white matter) and timing of the injury progression [25, 26]. In vitro studies have characterized actions of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in microglia [36, 37]. Microglia/macrophages can have both a protective and/or a deleterious role following injury and any change in microglial function in an immature brain can affect its role in normal development [38–40].

The purpose of this study is to further characterize the temporal changes in microglial phenotype and expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines at different time points after maternal inflammation as a step toward identifying pharmacological agents and time course for therapies for targeting neuroinflammation. In this study we demonstrate that in utero exposure to inflammation results in a predominantly pro-inflammatory microglial phenotype that persists in the postnatal period in the periventricular region, and that in vivo imaging of TSPO may be a sensitive biomarker of treatment response.

Material and Methods

Animal model

All animal procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at Wayne State University (PET imaging) and Johns Hopkins University. Timed-pregnant New Zealand white rabbits were purchased from Robinson Services, Inc. (Mocksville, NC). After one week of acclimation, the pregnant rabbits were randomly divided into control saline (CS, n=5) and Endotoxin (n=5) groups and underwent laparotomy at gestational day 28 (G28). 1 mL of saline or 1 mL of saline containing 20 μg/kg of LPS (E.coli serotype O127:B8, Sigma Aldrich, St Louis MO) was injected along the length of the uterus as previously described [10, 41]. Kits were studied at G29, PND1 and PND5. For the study at G29, dams were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital (120 mg/kg) intravenously. Fetuses were quickly removed, and the fetal brains were harvested for immunostaining, ELISA and real-time PCR. For the studies at PND1 and PND5 (or longer-term), dams were allowed to deliver spontaneously at-term (G31), and the kits were placed in an incubator and fed as described previously [42]. The neurobehavioral testing of the neonatal kits were evaluated as previously described [10,43]. Following behavioral testing, the kits were euthanized with 120 mg/kg pentobarbital on PND1 and PND5, and the brains were harvested for immunostaining, ELISA and real-time PCR.

Immunohistochemistry

Rabbit kits were anesthetized and intracardially perfused with saline followed by 10% formalin at G29, PND1 and PND5. Brains were post-fixed for 24 h and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose. 30 μm sections were cut with a cryostat and mounted onto poly-L-lysine coated slides (Sigma Aldrich, MO, USA). The sections were blocked with 5% donkey serum, incubated with goat anti-IBA1 (1:250, Abcam, MA, USA), rat anti-CD11b (1:100, Genetex, CA, USA) and mouse anti-CD45 (1:100, Bio-Rad, CA, USA), or goat anti-IBA1 (1:250, Abcam, MA, USA) and rabbit anti-iNOS (1:50, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), followed by fluorescent secondary antibodies (1:250, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) for 2h. For TSPO and Lectin co-staining, sections were blocked with 5% donkey serum, and incubated with goat anti-TSPO (1:500, GeneTex, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed, incubated with DyLight 594 lectin (1:250, Vector Laboratory) and fluorescent secondary antibody (1:250, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) for 2 h. Sections were washed and incubated in DAPI (1:1000) for 15 min. Immunolabelled sections were cover-slipped with Dako fluorescence mounting medium (VWR, PA, USA). All the images were captured on Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope, keeping similar settings during image acquisition for different groups.

ELISA

Coronal brain sections (1mm) were cut using a brain block, and the periventricular region, including part of the corpus callosum, corona radiata, internal capsule, caudate and dorsal hippocampus, were dissected from the beginning of the lateral ventricle to the beginning of the dorsal hippocampus (~65–75 mg tissue; n=5–6 kits/group/time point; denoted PVR). The total protein was isolated using the PARIS™ Kit (Protein and RNA isolation system, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), and protein concentration was determined using the BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). CD11b (MyBioSource, San Diego, CA), CD45 (LSBio, Seattle, WA), TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4 and IL-10 cytokines (R&D Systems, Inc., MN, USA) were measured using commercially available ELISA kits according to the manufacturer instructions.

Real Time PCR

Total RNA from the PVR (65–75 mg tissue) was extracted using the PARIS™ Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) according to manufacturer instructions (n=5–6 kits/each group/each time point). RNA samples were quantified using the Nanodrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer. Single-stranded complementary DNA (cDNA) was reverse transcribed from the total RNA samples by the high capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with RNase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reactions (qPCR) were conducted using Fast 7500 Real-time PCR systems (Life Technology, Applied Biosystems) with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Primers were custom designed and ordered from Integrated DNA technology. List of primers and their specifications are described in Table 1. Amplification conditions included 30 min at 48°C, 10 min at 95°C, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. For all samples, dissociation curves were acquired for quality control purposes. The comparative Ct method was used to assess differential gene expression between CS and endotoxin groups at different time points. First, gene expression levels for each sample were normalized to the expression level of the housekeeping gene encoding Glyceraldehydes 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) within a given sample (ΔCt); the difference between the endotoxin and CS groups was used to determine the ΔΔCt. The log2-ΔΔCt gave the relative fold change in gene expression of the CS and endotoxin kits.

Table 1.

Primers for performing real-time-PCR.

| Gene | Accession Number | Forward Primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSPO | XM_002723644.2 | ACT TGA ACC TTC ACC CAT GCA GGA | AAG CAG TTA CAG AGG GAG CGT |

|

| |||

| Il-12A | XM_008266409.1 | TCC AGT GCC TTA ACC ACT CCC AAA | ACT CCA GTG GTA AAC AGG CCT TCA |

| IL-12B | XM_002710347.2 | ACC TTG AGG TGA TGC TGG ATG CTA | ACA TGC CGG GAA TTC TTC AAT GGC |

|

| |||

| IL-23A | XM_002711079.2 | ATC CAG TGT GAA GAT GGC TGT GAC | AAT GTC TGA GCC CAA CAG CTT CTC |

| IL-17A | XM_002714498 | CCA GCA AGA GAT CCT GGT CCT A | ATG GAT GAT GGG GGT TAC ACA G |

|

| |||

| IL-17F | XM_008263041.1 | AAA ATC CCA AAG TGG AGG ATG C | AGC GGT TCT GGA AGT CAT GTG T |

|

| |||

| IL-18 | NM_001122940 | TCT TCA TGG ACC AAG GAC AGC AAC | AGG CTT ACA GCC ATG CCT CTA GTA |

| iNOS | U85094 | CAG GAC CAC ACC CCC TCG GA | AGC CAC ATC CCG AGC CAT GC |

|

| |||

| STAT-1 | XM_002712346.2 | TCG GAG GTA CTG AGT TGG CAG TTT | ATA AGA CCA TCG AGG CCG GCA TTA |

|

| |||

| STAT-3 | XM_002719395.2 | ACA TCC TGG GCA CAA ACA CCA AAG | AAT CAG GGA GGC ATC ACA ATT GGC |

|

| |||

| STAT-6 | XM_002720937.2 | TTT GCA CAG CTT GCT GGA AAC TCC | AGA TCT GGA TCC TCT TCA GCA CCA |

| GAPDH | NM_001082253 | TGA CGA CAT CAA GAA GGT GGT G | GAA GGT GGA GGA GTG GGT GTC |

MicroPET

Longitudinal MicroPET imaging using [11C] PK11195 was performed on newborn rabbits exposed to endotoxin or saline in utero over time (between PND 1 and PND 17) for in vivo evaluation of activated microglia as previously described [43]. In brief, PET scans were performed using a microPET R4 tomograph (Siemens Preclinical Solutions). Following anesthesia with 0.1–0.2% isoflurane, the rabbit kits were positioned on the head holder and placed on the microPET bed. The kits were injected intravenously with 10–20 MBq of [11C]PK11195 (half-life: 20 min), and a 60-min list mode data acquisition in 3D mode was initiated. The list mode data were subsequently rebinned into discrete time frames (6 × 10 min), and attenuation-corrected sinograms reconstructed using the ordered subset expectation-maximization iterative algorithm, yielding an isotropic image resolution of about 2 mm full width at half maximum. The images were processed using the AMIDE software (A Medical Image Data Examiner, version 1.0.4). The activity was standardized between animals by dividing the mean tracer concentration (in MBq per cubic centimeter) at each time point by the injected activity (in MBq) per weight (in grams) and expressed as standardized uptake values (SUV). The slope of the SUV curves derived from the whole acquisition period (0–60 min) was then used as a measure of microglial activation in the brain. Thus, a positive uptake slope indicates specific binding of the tracer to the TSPO on activated microglia, while a negative uptake slope indicates initial accumulation of the tracer in tissue, followed by washout due to weak nonspecific binding.

Locomotor activity

The locomotor activity of the rabbit kits was assessed with Opto-Varimex-4 Auto Track System (Columbus Instruments, Ohio, USA). The optovarimex consists of an open chamber 23.5 × 23.5× 21 cm with infrared optical beam sensors comprised of a detector and emitter on either sides of the cage. The autotrack system senses motion in the X and Y direction with a grid of infrared beams. Vertical motion (like head movement) was detected by a second set of photocells placed above the kits. The interruptions in the X and Y beams provide the location and distance traveled by the kits. The apparatus was placed in the test room under the same conditions as the room in which the kits were housed (~22°C, 12 h light-dark cycle). On PND1 and PND5 rabbit kits were transferred to the apparatus, and the spontaneous activity was recorded for 10 min. The recording was performed at a similar time (between 9–11am) in the morning at PND1 and PND5, and the animals were not disturbed during recording. Following the recording, the rabbit kits were returned to their home cage. The distance traveled (DT) by the kit (cm), resting time (RT) (s), large ambulatory movement (AT) (s), horizontal counts (HC), new beam breaks (AC), vertical sensor counts (VC), clockwise rotation (CR), counterclockwise rotation (CCR) and speed (calculated by DT/AT) were measured and compared between control and endotoxin groups.

Statistical Analyses

All data are expressed as means (±SD). Generalized estimating equations, which controls for the nesting of pups within litters was used to examine group differences. Due to heterogeneity of variance between the groups, data were transformed to ranks for the analysis. p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

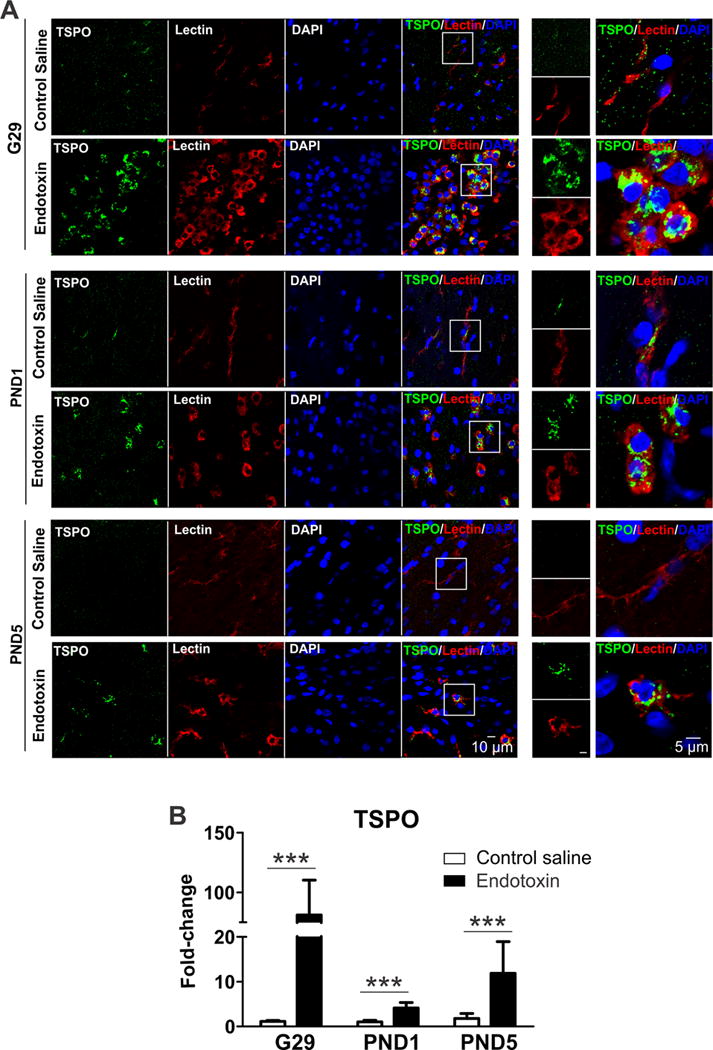

PVR of endotoxin kits have increased amoeboid microglia that co-stain for TSPO

An increase in microglial staining was seen in the periventricular white matter regions of the endotoxin kits as previously described by us in PND1 kits. Tomato lectin stained microglia/macrophages in the periventricular white matter areas (corpus callosum, angle of the lateral ventricle and the internal capsule) in the CS kits were ramified with long branching processes and small soma, while the microglia in the endotoxin group were amoeboid with short processes, indicating extensive microglia ‘activation’ at G29, PND1 and PND5 (Fig. 1A). TSPO has been shown to be upregulated in activated microglia [44, 45]. The microglia in the endotoxin kits at G29, PND1 and PND 5 had increased expression of TSPO as shown by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

In addition, we assessed the TSPO mRNA levels at G29, PND1 and PND5 in the PVR. We found that TSPO mRNA expression significantly increased in the endotoxin kits at G29 (p<0.001), PND1 (P<0.001) and PND5 (P<0.001) when compared to age-matched CS kits (Fig. 1B).

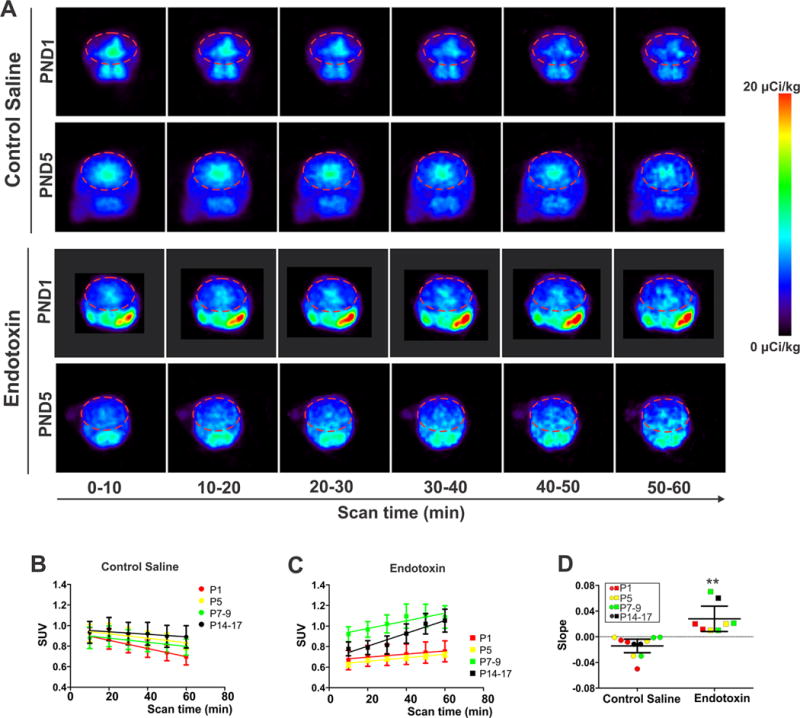

Increased TSPO binding measured in vivo in kits exposed to maternal inflammation

We confirmed the persistent increase in TSPO expression and microglial activation in endotoxin kits by in vivo PET imaging of postnatal rabbit kits. Consistent with our previous report [11], we found that there was selective binding of the TSPO ligand [11C]PK11195 in the brain at PND1 in the endotoxin kits compared to the CS kits. In addition we noted that this increased binding persisted in the endotoxin kits even at older ages up to PND17 (Fig. 2A, C). The extent of microglial activation was estimated by the slope of the SUV curves derived from the whole acquisition period (0–60 min) of the scan. Endotoxin kits at all ages demonstrated a positive uptake slope indicating specific binding of the tracer to TSPO on activated microglia (Fig. 2C,D), while CS kits had a negative uptake slope indicating initial non-specific accumulation of the tracer in tissue, followed by washout due to lack of specific binding (Fig, 2B, D). This indicates that microglial activation is persistent in the endotoxin kits up to 17 days after birth while CS kits did not demonstrate microglial activation at any time.

Fig. 2.

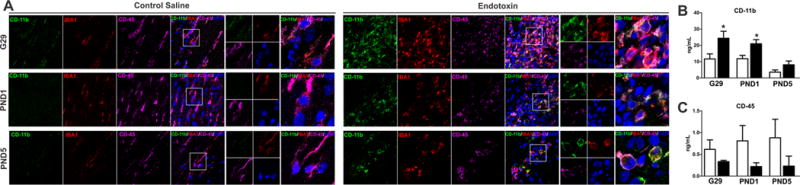

Changes in microglial cell surface markers expression in kits exposed to maternal inflammation

In order to further characterize the microglia phenotype at different time points after endotoxin administration (G29, PND1 and PND5) we assessed microglia for CD11b and CD45 expression [46]. Qualitative assessment of microglia in the PVR of young rabbits indicated that the microglial cells in CS kits had low levels of CD11b and constitutively expressed CD45 at all three time points. In contrast, the microglial cells in endotoxin kits had elevated expression of CD11b at all three time points (G29, PND1 and PND5), compared with CS kits (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Quantification of ELISA data confirmed that CD11b expression significantly increased in endotoxin kits at G29 (p<0.05) and PND1 (p<0.05), compared to their age-matched CS kits (Fig. 3B). Conversely, CD45 expression was decreased in endotoxin kits, compared to age-matched CS kits, but did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3C).

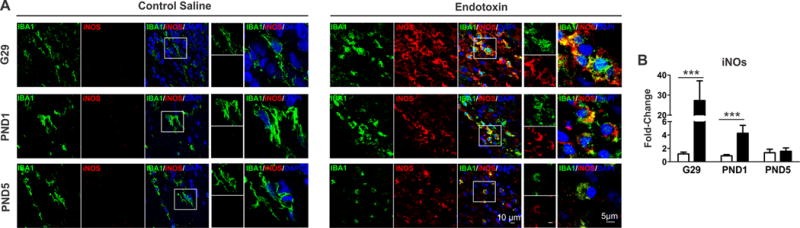

Increased iNOS expression in kits exposed to maternal inflammation

Microglial cells have been shown to upregulate iNOS expression in response to various pro-inflammatory stimuli. In accordance, here we observed an increase of iNOS expression in activated microglia in PVR in endotoxin kits (Fig. 4A). In addition, iNOS mRNA expression in PVR regions significantly increased at G29 (p<0.001) and PND1 (p<0.001) in endotoxin kits (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

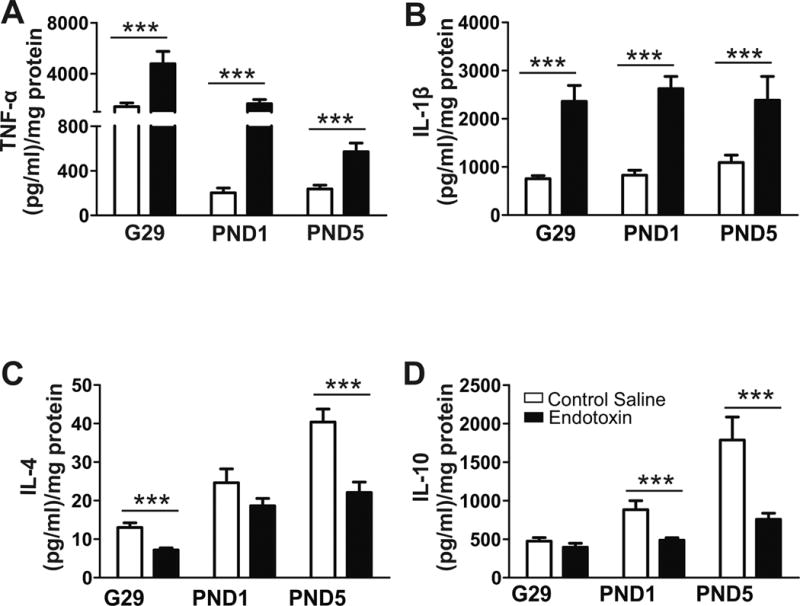

Protein expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines

Pro-inflammatory cytokine levels significantly increased in the PVR at G29, PND1 and PND5 in endotoxin kits compared to age-matched CS kits (TNF-α p<0.001; IL-1β p<0.001 for all ages) (Fig. 5A, B). Conversely, there were lower levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 in the endotoxin kits compared to CS kits with the lowest levels in both noted at PND5 (p<0.001) (Fig. 5C, D), indicating that there is a persistent pro-inflammatory milieu in the PVR after maternal intrauterine inflammation that is not countered by an adequate anti-inflammatory response.

Fig. 5.

Inflammatory marker mRNA expression

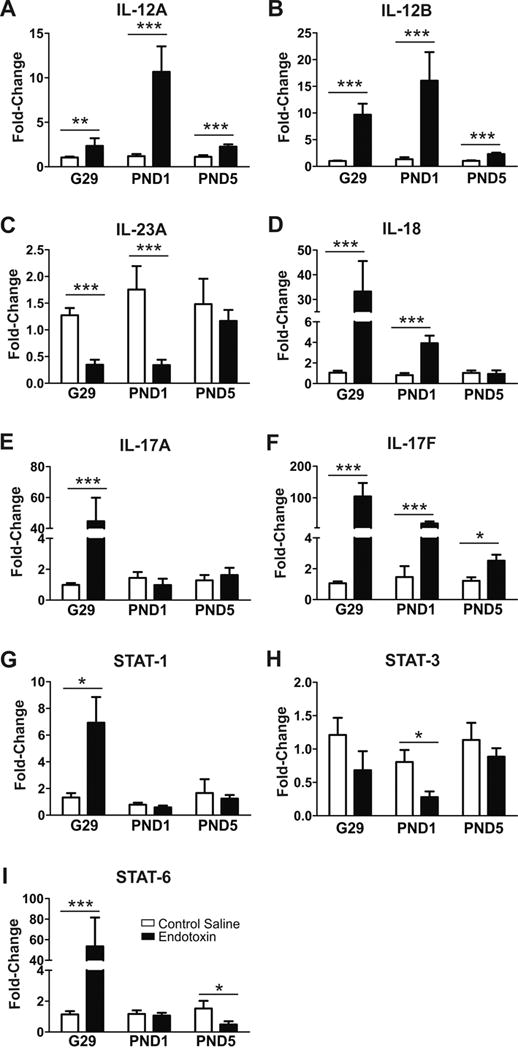

IL-12 and IL-23

There were significant increases in mRNA expression of IL-12A (G29, p<0.01; PND1, p<0.001; PND5, p<0.001) (Fig. 6A) and IL-12B (G29, p<0.001; PND1, p<0.001; PND5, p<0.001) noted in the endotoxin kits (Fig. 6B), while IL-23A mRNA levels significantly decreased at G29 (P<0.001) and PND1 (p<0.001) in endotoxin kits compared to age-matched CS kits (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

IL-17 & IL-18

We found that IL-18 mRNA level was significantly higher at G29 (p<0.001) and PND1 (p<0.001) in endotoxin kits, compared with CS kits (Fig. 6D). mRNA expression of IL-17A was significantly elevated in only G29 brain (p<0.001), whereas IL-17F expression was significantly higher in G29 (p<0.001), PND1 (p<0.001) and PND5 (p<0.001) in endotoxin kits, compared to CS kits (Fig. 6E, F).

Differentially regulated STATs

The JAK (Janus kinase)-STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) signaling pathway is involved in gene regulation during development, hormone release, inflammation or tumorigenesis in the central nervous system [47]. STAT-1, STAT-3 and STAT-6 expressions are high during embryonic stages and gradually decrease during postnatal development and into adulthood [48]. JAK-STAT signaling pathway is activated during inflammation, and we measured mRNA levels of STAT-1, STAT-3 and STAT-6. We found that STAT-1 expression significantly increased in endotoxin kits at G29 (p<0.05), but not at PND1 and PND5, compared to CS kits (Fig. 6G). Although there was a decrease in STAT-3 levels on G29 and PND1, it reached significance only at PND1 (p<0.05), when compared with the CS kits (Fig. 6H). STAT-6 level significantly increased at G29 (p<0.001), but significantly decreased at PND5 in endotoxin kits (p<0.05) (Fig. 6I).

Impaired locomotion in kits exposed to maternal inflammation

The distance traveled, resting time, large ambulatory movements, horizontal counts, new beam breaks, speed and numbers of vertical movements were measured and compared between CS and endotoxin groups. We found that kits exposed to maternal inflammation induced by LPS at G29 had reduced locomotor activity at PND1 and PND5, as indicated by the reduction in distance traveled (DT), large ambulatory movements (AT) and the horizontal counts (HC), new beam breaks (AC), as well as an increase in resting time (RT) (Table 2). In addition, the vertical movements (VC) significantly decreased in endotoxin group at PND5, suggesting the vertical body movements, including head movements, were significantly impacted by maternal inflammation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of open field motor activities were provided using mean ± SEM

| Day 1 | Day 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS (n=25) | CP (n=49) | P value CS vs. CP for Day1 | CS (n=18) | CP (n=24) | P value CS vs. CP for Day5 | P value CS vs. CP over Day1 to Day 5 | |

| DT (cm) | 584.9±36.1 | 376.8±38.9 | 0.03 | 1017.1±70.1 | 671.7±66.0 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| RT (s) | 50.8±4.5 | 109.3±12.6 | 0.01 | 25.6±3.6 | 68.2±13.7 | <0.01 | 0.02 |

| AT (s) | 178.4±5.0 | 131.5±13.0 | <0.01 | 227.7±5.6 | 175.3±12.6 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| HC | 1133.3±45.3 | 800.1±83.1 | <0.01 | 2198.7±119.7 | 1500.7±150.2 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| AC | 670.8±33.9 | 474.2±54.0 | 0.01 | 1481.4±106.5 | 923.0±98.6 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| VC | 113.4±9.7 | 91.9±28.4 | 0.12 | 854.9±89.7 | 440.6±82.1 | 0.03 | <0.01 |

| CR | 14.3±0.6 | 12.4±1.3 | 0.66 | 24.7±1.3 | 19.3±1.7 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| Speed (cm/s) | 3.2±0.1 | 2.8±0.1 | 0.96 | 4.3±0.2 | 3.7±0.3 | 0.96 | 0.12 |

Wherever applicable, P values were adjusted using Bonferroni correction; DT: Distance traveled by the kit (in cm); RT: Resting time when no movements (in sec); AT: Large ambulatory movements (in sec); HC: Horizontal counts; AC: New beam breaks; VC: Vertical sensor counts; CR: Clockwise rotation; Speed is calculated by dividing DT/AT.

Discussion

Maternal intrauterine infection results in a fetal inflammatory response syndrome (FIRS), mediated by maternal pro-inflammatory cytokines [49, 50]. FIRS increases the risk of preterm delivery, intra-ventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia and subsequently CP [51, 52]. We have demonstrated that LPS induced maternal inflammation in a rabbit model replicates many features of CP and mimics FIRS mediated neonatal brain injury in patients [33, 34, 42]. In this study, we utilized our previously established rabbit model to assess the temporal progression of microglial activation in vivo with PET and to characterize specific microglial phenotype markers and cytokines in the fetal and neonatal brains at different time points post-injury. We found that kits exposed to maternal intrauterine endotoxin demonstrated microglial activation and neuroinflammation for at least 7 days post-insult evidenced by 1) enhanced TSPO mRNA expression and immunoreactivity in ameboid microglia; 2) increased CD11b level with a concomitant decline in the CD45 level; 3) significantly elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines and iNOS, accompanied with decreased anti-inflammatory makers; and 4) differentially regulated mRNA expression of STAT-1, 3 and 6 in the periventricular areas in endotoxin kits. Furthermore, increased [11C]PK11195 binding to TSPO in endotoxin kits was detected up to PND17. Findings in this paper demonstrate that maternal inflammation induced pro-inflammatory microglial activation in the fetal and neonatal white matter regions that persisted in the postnatal period, which may guide therapeutic intervention aimed at repair and recovery in the postnatal period.

Postmortem studies of patients with PVL have shown that activated microglia and astrocytes are present irrespective of the etiology [53]. Microglia/macrophages play a key role after CNS injury, and can have both protective and deleterious effects based on the timing and type of insults [38, 54–58]. Recent studies show that specific environmental signals are able to induce different polarization states (pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory) of microglial cells [37, 59]. Microglia undergo a change in the expression of surface markers during embryonic and postnatal development related to their phenotype [59]. Studies have shown that pathogenic stimuli, such as IL-1β, fibrillar amyloid-β and HIV-1 gp120 can trigger the expression of CD11b via redox sensitive pathway [60]. CD11b expressing microglia play a key role in microglial-derived oxidative stress during neuroinflammation [61] and in turn, ROS (reactive oxygen species) and NO (nitric oxide) potentially enhance CD11b expression on activated microglia, thus increased CD11b directly correlates with oxidative injury [60], and corresponds to the severity of microglial activation in various neuroinflammatory diseases [62–64]. In our model the microglia in the PVR of endotoxin rabbits demonstrate both an increase in CD11b expression as well as upregulation of iNOS. In contrast, CD45 is a transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor which inhibits LPS induced microglial activation by significantly attenuating level of TNF-α and NO [65]. In our model, CD11b is expressed at very low levels in the brain of control animals while maternal inflammation induced intensive microglial activation and significantly increased CD11b in the fetal and neonatal brains. Interestingly, CD45 expression decreased in the neonatal rabbit brains exposed to maternal intrauterine inflammation. The increased CD11b in the fetal and neonatal brains post-injury, accompanied with decreased CD45 indicate a pro-inflammatory microglial phenotype in our CP model [66, 67].

The pro-inflammatory milieu in the PVR is further confirmed by the changes in the pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine expressions. In this study we found that the pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, and IL-17, along with iNOS, significantly increased in the white matter area at G29, PND1 and PND5; whereas, anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-10 significantly decreased in the endotoxin kits. Maternal inflammation results in an increase of cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α [68], which can cross the placenta and induce FIRS [49]. Increased TNF-α and IL-1β have been reported upon neuropathological testing of post-mortem neonatal brains with infection induced PVL [69], and are associated with a worse neurological outcome [70]. IL-12B activation can potentially induce iNOS and TNF-α production from microglia and macrophages [71]. iNOS can catalyze arginase on activated microglia to enhance NO formation. The increase in NO stimulates activated microglia to over-express CD11b-integrin surface receptors [60], which may explain our findings of increased CD11b expression in the endotoxin kits. Furthermore, iNOS expression has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative disorders, including multiple sclerosis, cerebral Adrenoleukodystrophy, Parkinson’s disease and HIV associated dementia, with demyelinating regions in the brains [72]. We have previously reported selective hypomyelination, decreased neuronal count and increased oxidative and nitrosative damage in PND5 CP kits compared to their age-matched controls [43]. In this study, we found that the endotoxin kits had motor deficits, especially deficits in vertical head and body moments, suggesting systemic inflammation may result in persistent oxidative stress and demyelination.

IL-17 is involved in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, cell adhesion molecules and growth factors, and is the key cytokine for the recruitment, activation, and migration of neutrophils [73]. Both astrocytes and microglia express IL-17 receptors and can produce IL-17 in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β [74], therefore, the elevated IL-1β in the periventricular region may contribute to the increased IL-17 production. Although we did not observe a large infiltration of T-cells in the brain in this model, it is possible that there is an interaction/cross talk between the peripheral immune cells and microglia in the brain that may promote the neuroinflammatory response. We have previously shown that maternal inflammation results in upregulation of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO), the rate limiting enzyme in tryptophan metabolism to kynurenine, in the placenta and fetal brain [75], which may decrease the proliferation and infiltration of T cells [76].

The JAK-STAT pathway is a classical signal transduction pathway for numerous cytokines and growth factors. Studies show that the developments of the Th1, Th2, and Th17 immune responses are mediated by STAT-4/STAT-1, STAT-6/STAT-5, and STAT-3 respectively [47, 77, 78]. In our study we found that STAT-1 and STAT-6 levels significantly increased at G29, suggesting upregulation of both Th1 and Th2 responses in the acute phase post-injury. Interestingly, STAT-6 level significantly decreased at PND5, indicating a suppressed Th2 response at a later time point post-injury, which might be responsible for the decreased anti-inflammatory response in endotoxin kits. STAT-3 mediates the IL-23 and IL-6 pathways [79, 80] and can both promote inflammation in some circumstances and inhibit it in others [81]. Evidence indicates that STAT-3 can inhibit toll like receptor (TLR) signaling either by inducing anti-inflammatory molecules or by a direct suppression of NF-κB [82]. In our study, we found that STAT-3 slightly decreased at G29 and significantly decreased at PND1, which might be responsible for the significantly decreased IL-23A levels at G29 and PND1. Activation of STAT-3 has been demonstrated in the astrocytes of post-mortem brain samples of patients with PVL and neonatal mice with conditional deficiency of STAT-3 in astrocytes had more pronounced hypomyelination when compared to WT following exposed to LPS treatment [83]. However, the role of STAT3 in our model needs to be further investigated.

Conclusions

In summary, maternal intrauterine inflammation induced by endotoxin leads to a pro-inflammatory environment in the PVR and pro-inflammatory microglial phenotype in the fetal and neonatal brain. While some elevated cytokines showed signs of a waning response at 7 days post-injury, IL-1β elevation was stable at 7 days post-injury and increased TSPO binding measured in vivo was present at 14–17 post-natal days. Data obtained in this study suggest that both cytokines and activated microglia may feed into and trigger each other to keep the white mater microenvironment pro-inflammatory, which might be responsible for hypomyelination, oxidative injury, neurobehavioral deficits and high mortality in this model and in patients with severe neonatal brain injury. Our study demonstrates that inflammation in the neonatal brain following a prenatal insult may be ongoing and persist for some time after birth. Therefore, postnatal therapies directed to promoting the microglial phenotype to enhance repair may be beneficial in neonates exposed to inflammation in utero or in the newborn period.

Highlights.

Maternal inflammation leads to pro-inflammatory microglial phenotype in the fetal and neonatal brain

11CPK11195 is an in vivo imaging biomarker that is upregulated in the postnatal period indicating ongoing microglial activation.

The pro-inflammatory microglial activation and environment provide a longer window of opportunity to attenuate the injury in the postnatal period.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by NIH R01 (R01HD069562) grant awarded to Dr. Sujatha Kannan. We thank Wilmer Core Grant (EY001765) for Vision Research, Microscopy and Imaging Core Module Facility.

Funding: This project is supported by NIH R01 (R01HD069562) grant awarded to Dr. Sujatha Kannan.

List of abbreviations

- CP

cerebral palsy

- PVR

periventricular region

- CS

control saline

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharides

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: All animal procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee

Consent for publication

Availability of data and material: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Authors’ contributions: Zhi Zhang performed experiments, analyzed data, wrote manuscript. Amar Jyoti performed experiments, analyzed data, wrote manuscript. Bindu Balakrishnan performed experiments. Monica Williams performed experiments. Sarabdeep Singh performed data analysis. Diane Chugani assisted with experimental design, PET analyses and writing the manuscript. Sujatha Kannan conceptualized the experiments and studies, analyzed data, wrote manuscript.

References

- 1.Adams Waldorf KM, McAdams RM. Influence of infection during pregnancy on fetal development. Reproduction. 2013;146(5):R151–62. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cordeiro CN, Tsimis M, Burd I. Infections and Brain Development. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2015;70(10):644–55. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleiss B, et al. Inflammation-induced sensitization of the brain in term infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57(Suppl 3):17–28. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagberg H, et al. The role of inflammation in perinatal brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(4):192–208. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chau V, et al. Chorioamnionitis in the pathogenesis of brain injury in preterm infants. Clin Perinatol. 2014;41(1):83–103. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu YW, Colford JM., Jr Chorioamnionitis as a risk factor for cerebral palsy: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;284(11):1417–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.11.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shatrov JG, et al. Chorioamnionitis and cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 Pt 1):387–92. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e90046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu YW, et al. Chorioamnionitis and cerebral palsy in term and near-term infants. JAMA. 2003;290(20):2677–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.20.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Shea TM, et al. The ELGAN study of the brain and related disorders in extremely low gestational age newborns. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85(11):719–25. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saadani-Makki F, et al. Intrauterine administration of endotoxin leads to motor deficits in a rabbit model: a link between prenatal infection and cerebral palsy. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;199(6):651.e1–651.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kannan S, et al. Magnitude of [(11)C]PK11195 binding is related to severity of motor deficits in a rabbit model of cerebral palsy induced by intrauterine endotoxin exposure. Dev Neurosci. 2011;33(3–4):231–40. doi: 10.1159/000328125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen MK, Guilarte TR. Translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO): molecular sensor of brain injury and repair. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;118(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graeber MB, Streit WJ. Microglia: immune network in the CNS. Brain Pathol. 1990;1(1):2–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1990.tb00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Haas AH, Boddeke HW, Biber K. Region-specific expression of immunoregulatory proteins on microglia in the healthy CNS. Glia. 2008;56(8):888–94. doi: 10.1002/glia.20663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Billiards SS, et al. Development of microglia in the cerebral white matter of the human fetus and infant. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497(2):199–208. doi: 10.1002/cne.20991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chugani DC, Kedersha NL, Rome LH. Vault immunofluorescence in the brain: new insights regarding the origin of microglia. J Neurosci. 1991;11(1):256–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-01-00256.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davalos D, et al. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(6):752–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madore C, et al. Early morphofunctional plasticity of microglia in response to acute lipopolysaccharide. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;34:151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chhor V, et al. Role of microglia in a mouse model of paediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain Behav Immun. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(1):57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanisch UK. Microglia as a source and target of cytokines. Glia. 2002;40(2):140–55. doi: 10.1002/glia.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoll G, Jander S. The role of microglia and macrophages in the pathophysiology of the CNS. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;58(3):233–47. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batchelor PE, et al. Activated macrophages and microglia induce dopaminergic sprouting in the injured striatum and express brain-derived neurotrophic factor and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci. 1999;19(5):1708–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01708.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.David S, Kroner A. Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(7):388–99. doi: 10.1038/nrn3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boksa P. Effects of prenatal infection on brain development and behavior: a review of findings from animal models. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(6):881–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagberg H, Gressens P, Mallard C. Inflammation during fetal and neonatal life: implications for neurologic and neuropsychiatric disease in children and adults. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(4):444–57. doi: 10.1002/ana.22620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Titomanlio L, et al. Pathophysiology and neuroprotection of global and focal perinatal brain injury: lessons from animal models. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;52(6):566–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McRae A, et al. Microglia activation after neonatal hypoxic-ischemia. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1995;84(2):245–52. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tahraoui SL, et al. Central role of microglia in neonatal excitotoxic lesions of the murine periventricular white matter. Brain Pathol. 2001;11(1):56–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2001.tb00381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallard C, et al. White matter injury following systemic endotoxemia or asphyxia in the fetal sheep. Neurochem Res. 2003;28(2):215–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1022368915400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rousset CI, et al. Maternal exposure to LPS induces hypomyelination in the internal capsule and programmed cell death in the deep gray matter in newborn rats. PediatrRes. 2006;59(3):428–33. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000199905.08848.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Favrais G, et al. Systemic inflammation disrupts the developmental program of white matter. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(4):550–65. doi: 10.1002/ana.22489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saadani-Makki F, et al. Intrauterine endotoxin administration leads to white matter diffusivity changes in newborn rabbits. J Child Neurol. 2009;24(9):1179–89. doi: 10.1177/0883073809338213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saadani-Makki F, et al. Intrauterine administration of endotoxin leads to motor deficits in a rabbit model: a link between prenatal infection and cerebral palsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6):651e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balakrishnan B, et al. Maternal endotoxin exposure results in abnormal neuronal architecture in the newborn rabbit. Dev Neurosci. 2013;35(5):396–405. doi: 10.1159/000353156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michelucci A, et al. Characterization of the microglial phenotype under specific pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory conditions: Effects of oligomeric and fibrillar amyloid-beta. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;210(1–2):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chhor V, et al. Characterization of phenotype markers and neuronotoxic potential of polarised primary microglia in vitro. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;32:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mallard C, et al. Astrocytes and microglia in acute cerebral injury underlying cerebral palsy associated with preterm birth. Pediatr Res. 2014;75(1–2):234–40. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt G, et al. Variability of ventricular premature complexes and mortality risk. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1996;19(6):976–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1996.tb03395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawson LJ, et al. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1990;39(1):151–70. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kannan S, et al. Decreased cortical serotonin in neonatal rabbits exposed to endotoxin in utero. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2010;31(2):738–749. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kannan S, et al. Dendrimer-based postnatal therapy for neuroinflammation and cerebral palsy in a rabbit model. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(130):130ra46. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kannan S, et al. Magnitude of [11C] PK11195 Binding Is Related to Severity of Motor Deficits in a Rabbit Model of Cerebral Palsy Induced by Intrauterine Endotoxin Exposure. Developmental Neuroscience. 2011;33(3–4):231–240. doi: 10.1159/000328125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kannan S, et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of neuroinflammation. J Child Neurol. 2009;24(9):1190–9. doi: 10.1177/0883073809338063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kannan S, et al. Microglial activation in perinatal rabbit brain induced by intrauterine inflammation: detection with 11C-(R)-PK11195 and small-animal PET. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(6):946–54. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.038539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hickman SE, et al. The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(12):1896–905. doi: 10.1038/nn.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicolas CS, et al. The role of JAK-STAT signaling within the CNS. JAKSTAT. 2013;2(1):e22925. doi: 10.4161/jkst.22925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De-Fraja C, et al. Members of the JAK/STAT proteins are expressed and regulated during development in the mammalian forebrain. J Neurosci Res. 1998;54(3):320–30. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981101)54:3<320::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gomez R, et al. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1998;179(1):194–202. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romero R, Erez O, Espinoza J. Intrauterine infection, preterm labor, and cytokines. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12(7):463–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dammann O, Leviton A. Maternal intrauterine infection, cytokines, and brain damage in the preterm newborn. Pediatric research. 1997;42(1):1–8. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leviton A, et al. Microbiologic and histologic characteristics of the extremely preterm infant’s placenta predict white matter damage and later cerebral palsy. The ELGAN Study. Pediatric research. 2010;67(1):95. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181bf5fab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haynes RL, et al. Nitrosative and oxidative injury to premyelinating oligodendrocytes in periventricular leukomalacia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62(5):441–50. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.5.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19(8):312–8. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polazzi E, Gianni T, Contestabile A. Microglial cells protect cerebellar granule neurons from apoptosis: evidence for reciprocal signaling. Glia. 2001;36(3):271–80. doi: 10.1002/glia.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faustino JV, et al. Microglial cells contribute to endogenous brain defenses after acute neonatal focal stroke. J Neurosci. 2011;31(36):12992–3001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2102-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tabas I, Glass CK. Anti-inflammatory therapy in chronic disease: challenges and opportunities. Science. 2013;339(6116):166–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1230720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aguzzi A, Barres BA, Bennett ML. Microglia: scapegoat, saboteur, or something else? Science. 2013;339(6116):156–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1227901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Butovsky O, et al. Identification of a unique TGF-beta-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(1):131–43. doi: 10.1038/nn.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roy A, et al. Reactive oxygen species up-regulate CD11b in microglia via nitric oxide: Implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2008;45(5):686–699. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Akiyama H, McGeer P. Brain microglia constitutively express β-2 integrins. Journal of neuroimmunology. 1990;30(1):81–93. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90055-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ling EA, Wong WC. The origin and nature of ramified and amoeboid microglia: a historical review and current concepts. Glia. 1993;7(1):9–18. doi: 10.1002/glia.440070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rock RB, et al. Role of microglia in central nervous system infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(4):942–64. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.942-964.2004. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gonzalez-Scarano F, Baltuch G. Microglia as mediators of inflammatory and degenerative diseases. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:219–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan J, Town T, Mullan M. CD45 inhibits CD40L-induced microglial activation via negative regulation of the Src/p44/42 MAPK pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(47):37224–37231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li F, et al. Lack of the scavenger receptor CD36 alters microglial phenotypes after neonatal stroke. J Neurochem. 2015;135(3):445–52. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Denker SP, et al. Macrophages are comprised of resident brain microglia not infiltrating peripheral monocytes acutely after neonatal stroke. J Neurochem. 2007;100(4):893–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Romero R, et al. Inflammation in pregnancy: its roles in reproductive physiology, obstetrical complications, and fetal injury. Nutrition reviews. 2007;65:S194–S202. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kadhim H, et al. Inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of periventricular leukomalacia. Neurology. 2001;56(10):1278–1284. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Armstrong-Wells J, Ferriero DM. Diagnosis and acute management of perinatal arterial ischemic stroke. Neurol Clin Pract. 2014;4(5):378–385. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jana M, Pahan K. IL-12 p40 homodimer, but not IL-12 p70, induces the expression of IL-16 in microglia and macrophages. Mol Immunol. 2009;46(5):773–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ghasemi M, Fatemi A. Pathologic role of glial nitric oxide in adult and pediatric neuroinflammatory diseases. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;45:168–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shabgah AG, Fattahi E, Shahneh FZ. Interleukin-17 in human inflammatory diseases. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31(4):256–61. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.40954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kawanokuchi J, et al. Production and functions of IL-17 in microglia. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;194(1–2):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Williams M, et al. Maternal Inflammation Results in Altered Tryptophan Metabolism in Rabbit Placenta and Fetal Brain. Dev Neurosci. 2017;39(5):399–412. doi: 10.1159/000471509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu WL, et al. Epstein-Barr virus infection induces indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages through p38/mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-kappaB pathways: impairment in T cell functions. J Virol. 2014;88(12):6660–71. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03678-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Knosp CA, et al. SOCS2 regulates T helper type 2 differentiation and the generation of type 2 allergic responses. J Exp Med. 2011;208(7):1523–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O’Shea JJ, et al. Genomic views of STAT function in CD4+ T helper cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(4):239–50. doi: 10.1038/nri2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang XO, et al. STAT3 regulates cytokine-mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(13):9358–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Durant L, et al. Diverse targets of the transcription factor STAT3 contribute to T cell pathogenicity and homeostasis. Immunity. 2010;32(5):605–15. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.El Kasmi KC, et al. General nature of the STAT3-activated anti-inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2006;177(11):7880–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang WB, Levy DE, Lee CK. STAT3 negatively regulates type I IFN-mediated antiviral response. J Immunol. 2011;187(5):2578–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nobuta H, et al. STAT3-mediated astrogliosis protects myelin development in neonatal brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(5):750–65. doi: 10.1002/ana.23670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]