Abstract

Exosomes are nanovesicles that participate in cell-to-cell communication and are secreted by a variety of cells including neurons. Recent studies suggest that neuronally-derived exosomes are detectable in plasma and that their contents likely reflect expression of various biomarkers in brain tissues. The receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) has been implicated in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and is increased in brain regions affected by AD. The goal of our project was to determine whether RAGE is present in plasma exosomes, and specifically exosomes derived from neurons. Exosomes were isolated from plasma samples (n=8) by precipitation (ExoQuick) and ultracentrifugation methods. Neuronally-derived exosomes were isolated using a biotin-tagged L1 Cell Adhesion Molecule (L1CAM) specific antibody and streptavidin-tagged agarose resin. RAGE expression was measured by Western blotting and ELISA. Western Blotting showed that RAGE is present in L1 CAM-positive exosomes isolated using both methods. Mean (SD) exosomal RAGE levels were 164 (60) pg/ml by ExoQuick and were highly correlated with plasma sRAGE levels (r=0.87, p=0.005), which were approximately 7.5-fold higher than exosomal levels. Weak to moderate correlations were found between exosomal RAGE and age, BMI, and cognitive function. These results show for the first time that RAGE is present in neuronally-derived plasma exosomes, and suggest that exosomal RAGE may be novel biomarker that reflects pathophysiological processes in the brain.

Keywords: receptor for advanced glycation endproducts, exosomes, cognition

INTRODUCTION

Over the last 10 years, accumulating evidence has emerged to support a key role for the receptor for AGEs (RAGE) in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1, 2]. By binding to both advanced glycation endproducts and amyloid-β (Aβ), RAGE contributes to the classical pathological features of AD by stimulating Aβ production in the brain and regulating the influx of circulating Aβ across the blood-brain barrier [3, 4]. RAGE also promotes senile plaque formation via tau hyperphosphorylation, synaptic dysfunction, and neuronal death [3, 5–7]. Soluble forms of RAGE (sRAGE) are generated by proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound receptor or by alternative splicing [8, 9]. In contrast to RAGE, sRAGE can prevent Aß transport into the brain and Aβ-induced neurotoxicity [7, 10]. These discoveries have led to the design of randomized clinical trials testing the efficacy of RAGE inhibitors in the treatment of mild-to-moderate AD [1, 2].

Both neuropathological and epidemiological studies show that RAGE expression is increased in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD compared to cognitively normal controls, whereas sRAGE levels are lower [3, 11–17]. Moreover, lower sRAGE levels are associated with cognitive impairment [11], as well as reduced brain volumes and increased cerebrovascular disease [18]. As such, low sRAGE levels may reflect an impaired endogenous protective response; yet, plasma/serum levels of sRAGE are non-specific. Thus, a blood-based RAGE biomarker that specifically reflects brain pathology is needed in epidemiological research to better understand the role of RAGE in neurodegenerative diseases.

Exosomes are small (~30–150 nm) extracellular vesicles of endosomal origin that are released in both a constitutive and stimulated manner by a variety of cell types [19]. Importantly, exosomes can be can released from neurons and detected in the blood, where their contents reflect the proteins, lipids, RNA, and other constituents of the parent cell. Given that exosomes may be able to cross the blood-brain barrier [20], measuring the contents of neuronally-derived exosomes found in blood has the potential to provide a brain “biopsy” that yields important information about pathophysiological processes occurring in the brain. Moreover, exosomes participate in cell-to-cell communication, removal of unwanted proteins, and transfer of pathogens (including prion-like misfolded proteins), mRNAs and miRNAs between cells, and consequently, are able to modulate protein synthesis and gene expression in recipient cells [21–23]. Previous studies indicate that neuronally-derived exosomes can be detected in plasma using L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1CAM), a surface protein located on neurons, and that their contents likely reflect protein expression in the brain [24–28]. Since exosomal RAGE may have important implications for AD, the purpose of this study was to determine whether RAGE is present in plasma exosomes, and specifically neuronally-derived exosomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

Blood samples were collected from obese older adults who were recruited to participate in a weight loss study, but failed to meet all eligibility criteria (n=8). Individuals reported to the laboratory in the morning after an overnight fast. Venous blood was drawn into EDTA tubes, centrifuged to collect the plasma fraction, and stored at −80°C until analysis. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was administered to assess global cognitive function [29]. MoCA scores were available for all but one participant. Written informed consent was provided prior to all data and blood collection.

Exosome Isolation from Plasma

Exosomes were isolated from plasma samples using two different methods: an ExoQuick precipitation method and an ultracentrifugation method, as we have described previously [30–32]. For the ExoQuick method, 0.5 ml plasma was centrifuged at 3000 × g for 15 minutes to remove cellular debris and collect supernates. 100 μl of ExoQuick Exosome Precipitation Solution (EXOQ; System Biosciences, Inc., Mountainview, CA) was added. Suspensions were incubated overnight and then centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 30 minutes. The supernatant from each sample was discarded and the remaining pellet was subjected to another centrifugation at 1500 × g for 5 minutes. All remaining trace fluid was removed, leaving a pellet containing exosomes. The exosome pellet was then suspended in lysis buffer for Western Blotting. For the ultracentrifugation method, one-half milliliter of plasma was gathered and subjected to serial centrifugations at 500 × g and 2000 × g for five minutes each. The samples were transferred to fresh vials and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g to remove microvesicles. Supernates were collected and filtered through 0.22 μm filters. Afterwards, suspensions were ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × rpm. The resultant pellet, which contained exosomes, was then suspended in lysis buffer for Western Blotting.

Isolation of Neuronally-derived Exosomes From Plasma

Neuronally-derived exosomes were isolated from plasma as previously described [33]. Briefly, 0.5 ml of plasma was incubated with 0.15 ml of thromboplastin-D (Fisher Scientific, Inc., Hanover Park, IL) at room temperature for 60 minutes, followed by addition of 0.35 ml of calcium- and magnesium-free Dulbecco’s phosphatase buffered saline (DPBS) with protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Pierce Halt, Thermo Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL). After centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 20 minutes, supernates were mixed with 252 ml of ExoQuick exosome precipitation solution and incubated for 1 hour at 4°C. Resultant exosome suspensions were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C and each pellet was resuspended in 250 ml of DPBS with inhibitor cocktails. Each sample was incubated for 1 hour at 4°C with 1 mg of mouse anti-human CD171 (L1CAM]) biotinylated antibody (clone 5G3, eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and then 25 ml of streptavidin-agarose resin (Thermo Scientific, Inc.) plus 50 ml of 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA; 1:3.33 dilution of Blocker BSA 10% solution in DPBS). After centrifugation at 200 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C and removal of the supernate, each pellet was suspended in 50 μl of 0.05 M glycine-HCl (pH 3.0) by vortexing for 10 seconds. Each suspension then received 500 μl of M-PER mammalian protein extraction reagent (Thermo Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL) that had been adjusted to pH 8.0 with 1 M Tris-HCl (Ph 8.6) and contained cocktail inhibitors. The suspensions were incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes, vortex-mixed for 15 seconds, and then stored at −80°C until Western Blotting.

Western Blotting

Total cell lysates were prepared using 1× RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail solution. Approximately, 40–60 μg of protein lysate per sample was denatured in Laemmli sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on Tris-glycine gel. The separated proteins were transferred on to a nitrocellulose membrane followed by blocking with 5% non-fat milk powder (w/v) in Tris-buffered saline (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were probed for RAGE protein using a rabbit polyclonal antibody corresponding to amino acids 39–58 of human RAGE (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), followed by the appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and then visualized by an electrochemiluminescence detection system.

RAGE Assay

Total RAGE was measured in plasma and exosomes isolated from plasma using a commercially available ELISA that uses a monoclonal antibody raised against amino acids Gln24-Ala344 in the N-terminal extracellular domain of human RAGE (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). This assay quantifies all circulating isoforms including cleaved isoforms shed into the bloodstream by extracellular metalloproteinases as well as secreted isoforms generated by alternative splicing.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

As shown in Table 1 the participants in this study were primarily older white females. All were obese and had normal cognitive function based on a cut-off score of 22 for the MoCA [34].

Table 1:

Clinical characteristics of study participants (n=8)

| Clinical Characteristic | Mean ± SD or N (%) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 69.5 ± 4.1 | 65 – 77 |

| Female gender | 7 (87.5%) | -- |

| White race | 6 (75%) | -- |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 36.3 ± 3.7 | 31.0 – 42.3 |

| MoCA | 25.1 ± 1.6 | 23 – 28 |

| Plasma sRAGE (pg/ml) | 1225±618 | 602 – 2145 |

| Exosomal RAGE (pg/ml) | 164 ± 60 | 93 – 248 |

RAGE is present in plasma exosomes

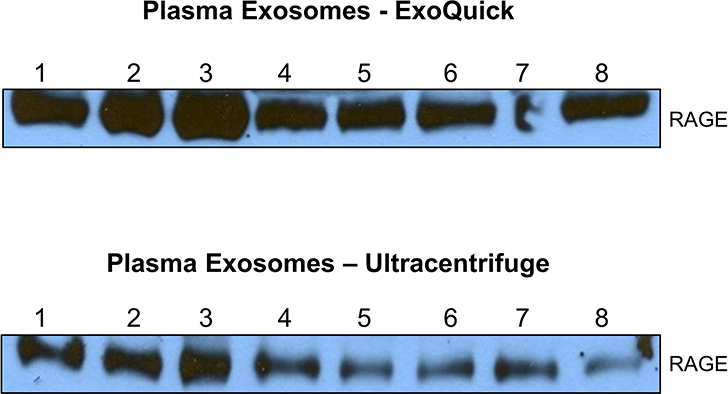

Western Blot results showed that RAGE was present in plasma exosomes isolated using both the precipitation and ultracentrifugation methods (Figure 1). Exosomal RAGE expression was confirmed by ELISA where mean (SD) RAGE levels were 1225 (618) pg/ml in plasma and 164 (60) pg/ml in plasma exosomes obtained via ExoQuick (Table 1). Although RAGE levels in plasma exosomes were approximately 13% of that found in the plasma fraction, plasma and exosomal RAGE levels were highly correlated (r=0.87, p=0.005). Moreover, the assay results were robust, with intra-assay coefficients of variation of <4%. Protein concentrations in the samples obtained via ultracentrifugation were very dilute and were generally below the minimum detectable dose for the RAGE ELISA (<16 pg/ml).

Figure 1. RAGE is present in plasma exosomes.

Exosomes were isolated from plasma by ExoQuick precipitation method or by ultracentrifugation. Exosomes were lysed and analyzed for RAGE expression by Western blotting and representative blots are shown.

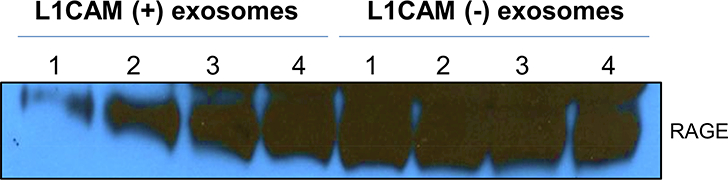

RAGE is present in neuronally-derived plasma exosomes

Plasma samples from 4 participants were used to isolate neuronally-derived exosomes using an antibody to L1CAM. Western Blot results confirmed that RAGE is detectable in both L1CAM-positive (i.e., neuronally-derived) and L1CAM-negative exosomes (Figure 2). The results show that RAGE expression is relatively lower in L1CAM-positive exosomes, and highly variable, compared to L1CAM-negative exosomes.

Figure 2. RAGE is present in neuronally-derived exosomes from plasma.

L1CAM-postive and L1CAM-negative exosomes were isolated from plasma as detailed in the methods and analyzed for RAGE expression by Western blotting. A representative blot is shown.

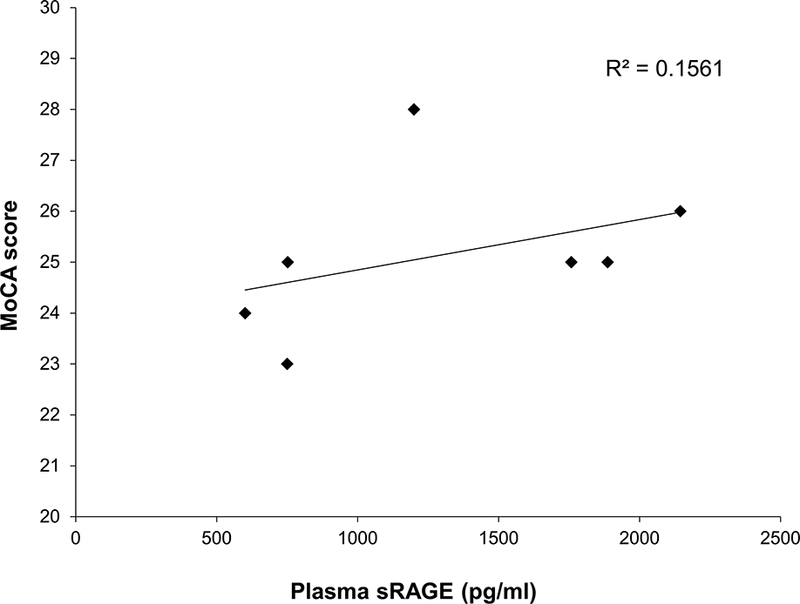

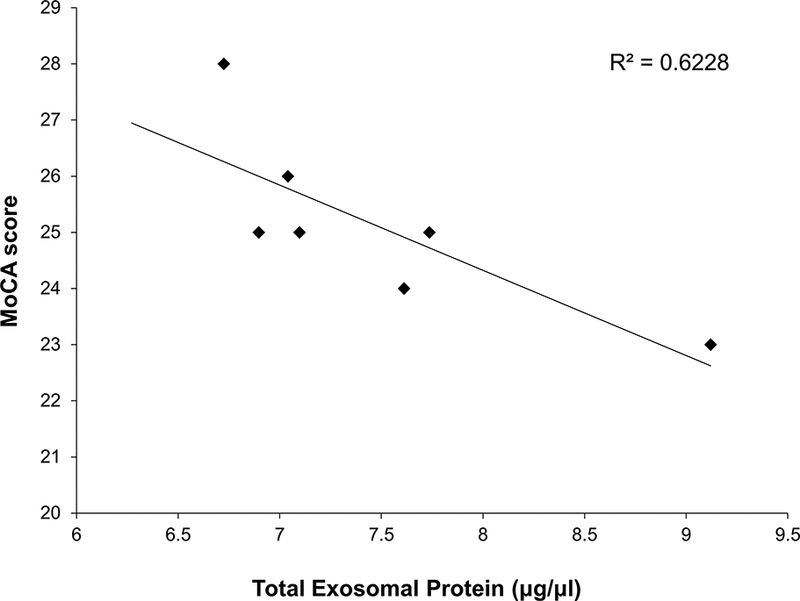

RAGE in plasma and plasma exosomes is correlated with cognitive function

A modest correlation was found between plasma sRAGE levels and MoCA score (r=0.40, p=0.38, Figure 3). RAGE levels in plasma exosomes were not correlated with MoCA (r=0.07, p=0.89); however, when exosomal RAGE was normalized to the total protein content, the association was stronger (r=0.25, p=0.58). This finding may be related to the significant association between MoCA score and total exosomal protein (r=−0.79, p=0.03) (Figure 4), which ranged from 6.27 μg/μl to 9.12 μg/μl. RAGE levels in both plasma and plasma exosomes were similarly correlated with BMI: r=−0.73, p=0.04 and r=−0.71, p=0.05, respectively. Weak to moderate correlations were also observed with age: r=−0.59, p=0.12 for plasma sRAGE and r=−0.28, p=0.50 for exosomal RAGE.

Figure 3.

Lower plasma sRAGE levels are associated with lower cognitive function.

Figure 4.

Higher total exosomal protein content is associated with lower cognitive function.

DISCUSSION

This study reports for the first time the discovery of a novel source of RAGE in the blood - exosomes. We have confirmed (via Western blot and ELISA) that plasma exosomes contain RAGE protein. Because exosomes participate in cell-to-cell communication and mediate many cellular processes, the presence of RAGE in exosomes suggests that the removal and/or transfer of RAGE between cells has important biological relevance. The presence of RAGE in neuronally-derived plasma exosomes also highlights potential implications for the development and progression of neurodegenerative diseases. Notably, RAGE expression in neuronally-derived plasma exosomes appears to be highly variable. Future studies should investigate whether this variability correlates with the onset of AD.

As has been shown previously [11], we found a positive association between plasma sRAGE levels and MoCA. Plasma RAGE reflects soluble isoforms, suggesting that low sRAGE levels are a risk factor for or a biomarker of cognitive impairment. In contrast, we found no association between exosomal RAGE levels and cognition. Since the ExoQuick method lyses the exosomes, the analysis of exosomal RAGE by the present ELISA likely quantifies both membrane-bound RAGE on the surface of the exosome and sRAGE found within the vesicle. The fact that these isoforms have differing associations with AD could explain the lack of association between exosomal RAGE and MoCA score.

Interestingly, another novel finding was the strong correlation between exosomal protein content and MoCA score. AD is characterized by the misfolding and aggregation of key proteins, and exosomes are known to participate in the transfer of unwanted proteins and pathogens [21]. As such, it is possible that the inverse association between exosomal protein content and MoCA score reflects a higher burden of misfolded or damaged proteins in individuals with greater cognitive impairment and the subsequent packaging of these proteins into exosomes for transfer or removal.

Using an exosomal biomarker derived from neuronal sources has the potential to not only facilitate the study of relevant brain pathology and neurodegeneration in clinical populations, but also aid in AD risk prediction. Our study suggests that exosomal RAGE may be a useful biomarker and/or therapeutic target in this regard. However, utilizing exosomes in the clinical setting will require greater knowledge of the mechanisms of biogenesis and secretion, as well as the development of more accurate methods to isolate and characterize exosomal fractions, including the origin and physiological function of different subpopulations [19]. Further research is needed to identify the exact RAGE isoforms present in exosomes (membrane-bound or soluble isoforms), determine where they are located (on the surface or within the vesicle), and better understand if and how trafficking of RAGE in plasma exosomes affects surrounding cells and contributes to pathophysiological processes.

In conclusion, we found that RAGE is detectable in plasma exosomes, and specifically exosomes derived from neurons. Despite the limitations of the current study (e.g., small sample size, non-specific RAGE assay), our findings contribute to the growing body of literature supporting a role for RAGE in the brain and in the pathogenesis of cognitive decline and dementia.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

RAGE is present in plasma exosomes

RAGE is present in neuronally-derived exosomes in plasma

Exosomal RAGE is weakly to moderately associated with age, BMI, and cognition

Higher total protein content in plasma exosomes is associated with worse cognition

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Alzheimer’s Association (grant number NIRGD-396460) and the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R21-CA199628 and R25-GM064249). The funding sources had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the writing of this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- BMI

body mass index

- L1CAM

L1 cell adhesion molecule

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- RAGE

receptor for advanced glycation endproducts

- sRAGE

soluble receptor for advanced glycation endproducts

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Burstein AH, Grimes I, Galasko DR, Aisen PS, Sabbagh M, Mjalli AM, Effect of TTP488 in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, BMC Neurol, 14 (2014) 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sabbagh MN, Agro A, Bell J, Aisen PS, Schweizer E, Galasko D, PF-04494700, an oral inhibitor of receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), in Alzheimer disease, Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 25 (2011) 206–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cai Z, Liu N, Wang C, Qin B, Zhou Y, Xiao M, Chang L, Yan LJ, Zhao B, Role of RAGE in Alzheimer’s Disease, Cellular and molecular neurobiology, 36 (2016) 483–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vitek MP, Bhattacharya K, Glendening JM, Stopa E, Vlassara H, Bucala R, Manogue K, Cerami A, Advanced glycation end products contribute to amyloidosis in Alzheimer disease, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 91 (1994) 4766–4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ko SY, Ko HA, Chu KH, Shieh TM, Chi TC, Chen HI, Chang WC, Chang SS, The Possible Mechanism of Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs) for Alzheimer’s Disease, PloS one, 10 (2015) e0143345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Li XH, Xie JZ, Jiang X, Lv BL, Cheng XS, Du LL, Zhang JY, Wang JZ, Zhou XW, Methylglyoxal induces tau hyperphosphorylation via promoting AGEs formation, Neuromolecular Med, 14 (2012) 338–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Byun K, Bayarsaikhan E, Kim D, Kim CY, Mook-Jung I, Paek SH, Kim SU, Yamamoto T, Won MH, Song BJ, Park YM, Lee B, Induction of neuronal death by microglial AGE-albumin: implications for Alzheimer’s disease, PloS one, 7 (2012) e37917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Raucci A, Cugusi S, Antonelli A, Barabino SM, Monti L, Bierhaus A, Reiss K, Saftig P, Bianchi ME, A soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is produced by proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound form by the sheddase a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10), FASEB J, 22 (2008) 3716–3727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yonekura H, Yamamoto Y, Sakurai S, Petrova RG, Abedin MJ, Li H, Yasui K, Takeuchi M, Makita Z, Takasawa S, Okamoto H, Watanabe T, Yamamoto H, Novel splice variants of the receptor for advanced glycation end-products expressed in human vascular endothelial cells and pericytes, and their putative roles in diabetes-induced vascular injury, Biochemical Journal, 370 (2003) 1097–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kojro E, Postina R, Regulated proteolysis of RAGE and AbetaPP as possible link between type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease, Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD, 16 (2009) 865–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang P, Huang R, Lu S, Xia W, Cai R, Sun H, Wang S, RAGE and AGEs in Mild Cognitive Impairment of Diabetic Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study, PloS one, 11 (2016) e0145521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen G, Cai L, Chen B, Liang J, Lin F, Li L, Lin L, Yao J, Wen J, Huang H, Serum level of endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation end products and other factors in type 2 diabetic patients with mild cognitive impairment, Diabetes Care, 34 (2011) 2586–2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liang F, Jia J, Wang S, Qin W, Liu G, Decreased plasma levels of soluble low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (sLRP) and the soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) in the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, J Clin Neurosci, 20 (2013) 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Emanuele E, D’Angelo A, Tomaino C, Binetti G, Ghidoni R, Politi P, Bernardi L, Maletta R, Bruni AC, Geroldi D, Circulating levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia, Arch Neurol, 62 (2005) 1734–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ghidoni R, Benussi L, Glionna M, Franzoni M, Geroldi D, Emanuele E, Binetti G, Decreased plasma levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products in mild cognitive impairment, Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996), 115 (2008) 1047–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nozaki I, Watanabe T, Kawaguchi M, Akatsu H, Tsuneyama K, Yamamoto Y, Ohe K, Yonekura H, Yamada M, Yamamoto H, Reduced expression of endogenous secretory receptor for advanced glycation endproducts in hippocampal neurons of Alzheimer’s disease brains, Arch Histol Cytol, 70 (2007) 279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhu H, Ding Q, Lower expression level of two RAGE alternative splicing isoforms in Alzheimer’s disease, Neurosci Lett, 597 (2015) 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hudson BI, Moon YP, Kalea AZ, Khatri M, Marquez C, Schmidt AM, Paik MC, Yoshita M, Sacco RL, DeCarli C, Wright CB, Elkind MS, Association of serum soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products with subclinical cerebrovascular disease: the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS), Atherosclerosis, 216 (2011) 192–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C, Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles, Annual review of cell and developmental biology, 30 (2014) 255–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Yin H, Betts C, Lakhal S, Wood MJA, Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes, Nat Biotech, 29 (2011) 341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bellingham SA, Guo BB, Coleman BM, Hill AF, Exosomes: vehicles for the transfer of toxic proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases?, Front Physiol, 3 (2012) 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hoy AM, Buck AH, Extracellular small RNAs: what, where, why?, Biochem. Soc. Trans, 40 (2012) 886–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO, Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells, Nature cell biology, 9 (2007) 654–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Goetzl EJ, Boxer A, Schwartz JB, Abner EL, Petersen RC, Miller BL, Carlson OD, Mustapic M, Kapogiannis D, Low neural exosomal levels of cellular survival factors in Alzheimer’s disease, Annals of clinical and translational neurology, 2 (2015) 769–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Goetzl EJ, Boxer A, Schwartz JB, Abner EL, Petersen RC, Miller BL, Kapogiannis D, Altered lysosomal proteins in neural-derived plasma exosomes in preclinical Alzheimer disease, Neurology, 85 (2015) 40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Goetzl EJ, Kapogiannis D, Schwartz JB, Lobach IV, Goetzl L, Abner EL, Jicha GA, Karydas AM, Boxer A, Miller BL, Decreased synaptic proteins in neuronal exosomes of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, Faseb j, 30 (2016) 4141–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Goetzl EJ, Mustapic M, Kapogiannis D, Eitan E, Lobach IV, Goetzl L, Schwartz JB, Miller BL, Cargo proteins of plasma astrocyte-derived exosomes in Alzheimer’s disease, Faseb j, 30 (2016) 3853–3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Winston CN, Goetzl EJ, Akers JC, Carter BS, Rockenstein EM, Galasko D, Masliah E, Rissman RA, Prediction of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia with neuronally derived blood exosome protein profile, Alzheimer’s & dementia (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 3 (2016) 63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H, The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc, 53 (2005) 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Schlaepfer IR, Nambiar DK, Ramteke A, Kumar R, Dhar D, Agarwal C, Bergman B, Graner M, Maroni P, Singh RP, Agarwal R, Deep G, Hypoxia induces triglycerides accumulation in prostate cancer cells and extracellular vesicles supporting growth and invasiveness following reoxygenation, Oncotarget, 6 (2015) 22836–22856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ramteke A, Ting H, Agarwal C, Mateen S, Somasagara R, Hussain A, Graner M, Frederick B, Agarwal R, Deep G, Exosomes secreted under hypoxia enhance invasiveness and stemness of prostate cancer cells by targeting adherens junction molecules, Molecular carcinogenesis, 54 (2015) 554–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Panigrahi GK, Praharaj PP, Peak TC, Long J, Singh R, Rhim JS, Elmageed ZYA, Deep G, Hypoxia-induced exosome secretion promotes survival of African-American and Caucasian prostate cancer cells, Scientific reports, 8 (2018) 3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fiandaca MS, Kapogiannis D, Mapstone M, Boxer A, Eitan E, Schwartz JB, Abner EL, Petersen RC, Federoff HJ, Miller BL, Goetzl EJ, Identification of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease by a profile of pathogenic proteins in neurally derived blood exosomes: A case-control study, Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 11 (2015) 600–607. e601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Freitas S, Simoes MR, Alves L, Santana I, Montreal cognitive assessment: validation study for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease, Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 27 (2013) 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.