Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer prediction tools provide quantitative guidance for doctor-patient decision-making regarding biopsy. The widely used online Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial Risk Calculator (PCPTRC) utilized data from the 1990s based on six-core biopsies and outdated grading systems.

Objective

We prospectively gathered data from men undergoing prostate biopsy in multiple diverse North American and European institutions participating in the Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group (PBCG) in order to build a state-of-the-art risk prediction tool.

Design, setting, and participants

We obtained data from 15 611 men undergoing 16 369 prostate biopsies during 2006–2017 at eight North American institutions for model-building and three European institutions for validation.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis

We used multinomial logistic regression to estimate the risks of high-grade prostate cancer (Gleason score ≥7) on biopsy based on clinical characteristics, including age, prostate-specific antigen, digital rectal exam, African ancestry, first-degree family history, and prior negative biopsy. We compared the PBCG model to the PCPTRC using internal cross-validation and external validation on the European cohorts.

Results and limitations

Cross-validation on the North American cohorts (5992 biopsies) yielded the PBCG model area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) as 75.5% (95% confidence interval: 74.2–76.8), a small improvement over the AUC of 72.3% (70.9–73.7) for the PCPTRC (p < 0.0001). However, calibration and clinical net benefit were far superior for the PBCG model. Using a risk threshold of 10%, clinical use of the PBCG model would lead to the equivalent of 25 fewer biopsies per 1000 patients without missing any high-grade cancers. Results were similar on external validation on 10 377 European biopsies.

Conclusions

The PBCG model should be used in place of the PCPTRC for prediction of prostate biopsy outcome.

Patient summary

A contemporary risk tool for outcomes on prostate biopsy based on the routine clinical risk factors is now available for informed decision-making.

Keywords: Digital rectal exam, Family history, High-grade disease, Prostate cancer, Prostate-specific antigen, Risk prediction

1. Introduction

The decision to conduct a prostate biopsy for the suspicion of prostate cancer is far from trivial, with potential consequences including sepsis, over-diagnosis of indolent disease or, conversely, delayed diagnosis of an aggressive cancer [1,2]. The new emphasis on shared-decision making for medical procedures has increased interest in decision tools to allow improved explanation of risk during the physician–patient interaction [3]. Many of the risk tools were developed on large comprehensive cohorts, where statistical modeling integrated the influences of established risk factors, such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA), digital rectal exam (DRE), race, and age, on biopsy outcomes.

Two of the most commonly used risk tools were built on large prospective screening trials: the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) risk tool and the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) risk calculator (PCPTRC) [4,5]. Both trials were performed during the 1990s and hence based on the study populations and clinical practice standards of that time. The PCPT was a heavily screened population of primarily healthy North American white men, requiring a PSA ≤3 ng/ml and a normal DRE to enter the trial, annual PSA and DRE screening, and a required end-of-study biopsy at the end of 7 yr. The ERSPC comprised a near exclusively white European population also heavily screened [6,7]. These populations are not in accord with contemporary patients from diverse backgrounds who are likely to undergo limited screening during the lifetime and only ever encounter risk assessment after an elevated PSA prompts referral to a tertiary care center. Both the ERSPC and PCPT involved sextant biopsy and grading scheme current in the 1990s. Contemporary biopsies utilize 10–12 twelve cores and are subject to pathologic grading under contemporary schemes that reclassify some cancers to higher Gleason scores [8,9].

To better understand the relationships between prostate biopsy outcomes and established risk factors in heterogeneous cohorts, the Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group (PBCG) was formed in 2009 as a consortium collecting retrospective data from 10 screening studies and tertiary referral centers [10]. Validation of both the ERSPC and PCPT risk tools revealed differences in operating characteristics across the cohorts, demonstrating that validation is a property of both the risk tool and the validation cohort [11,12]. Significant amounts of missing risk factors prohibited robust conclusions and further use from the retrospective data. To ensure high data quality for production of a new prostate cancer risk tool based on heterogeneous contemporary populations and practice, the PBCG began prospective collection from participating centers in 2014. The new risk tool was to be modeled after the PCPTRC, with the hypothesis that such a risk tool would have better external validation for contemporary populations [13].

2. Patients and methods

Data from 11 participating sites under local internal review board approval were prospectively collected. Cleveland Clinic, Hamburg, Mayo Clinic, San Raffaele, Zurich, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), and University of California San Francisco (UCSF) were participating tertiary referral centers. Durham Veterans Affairs (VA) and San Juan VA served a lower socioeconomic status population with a high percentage of African Americans and Hispanics, respectively. Sunnybrook and UT Health were consortia that include main hospitals, tertiary referral centers, and associated community urology providers. Four sites also provided retrospective data for prostate biopsies performed in 2006 or later.

This risk tool predicts three outcomes on biopsy: high-grade disease (Gleason score ≥7), low-grade disease (Gleason score <7), and benign findings (no prostate cancer). We chose the study outcomes as they reflect the clinical purpose of the tool, which is to aid biopsy decision-making. It is unequivocal that although we may not treat a man with Gleason 3+4, we do need to at least evaluate it before making treatment decisions. The definition of high-grade as Gleason score 3+4 or higher is entirely conventional, being used, in addition to PCPTRC version 2.0, for numerous studies including the Stockhom-3 model, the ERSPC Rotterdam Section update, and the Canary Prostate Active Surveillance Study [13–16].

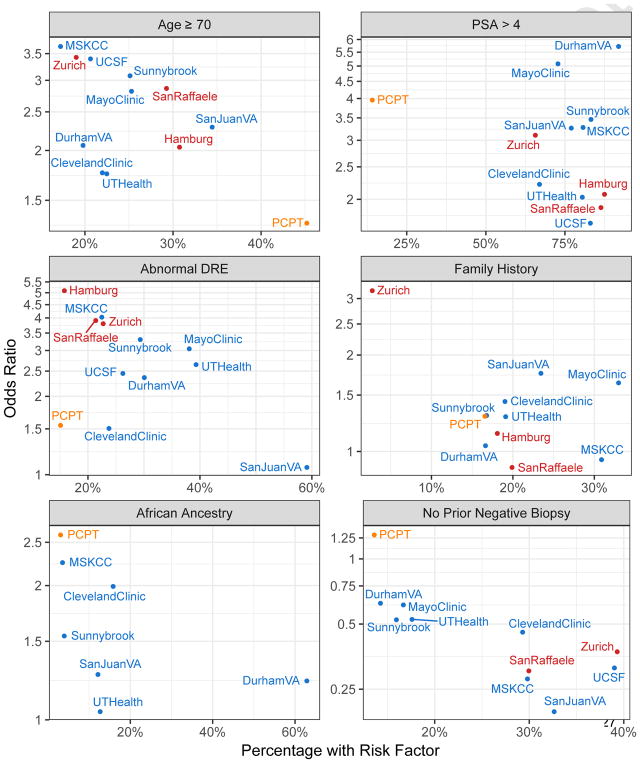

We compared patient and biopsy characteristics between the training and validation sets using chi-square and Wilcoxon tests. We examined the relationship between prevalence of the risk factors in each cohort to the odds ratio from a logistic regression of high-grade cancer on the risk factor alone for each of the PBCG cohorts, along with results from the PCPT population of 6664 biopsies used to build the PCPTRC version 2.0 [13]. We fit a multinomial logistic model to estimate risks of high- versus low-grade versus no cancer with predictors age, PSA (logarithmically transformed), DRE, African ancestry, first-degree family history, and prior negative biopsy history to data from all eight cohorts pooled together. Prostate volume was not included in the models as this requires an invasive test, a transrectal ultrasound, to obtain. The online PCPTRC allows missing values for DRE, family history, and negative prior biopsy history using marginal models fit without these covariates, and we followed the same procedure. For both model fitting and validation, we imputed missing values of African ancestry to be non-African; a sensitivity check determined results to be similar.

We compared the validation performance of the PBCB and PCPTRC models for the prediction of high-grade cancer versus the other endpoints combined (low-grade and no cancer) in terms of discrimination measured by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy measured by calibration curves, and clinical utility based on net benefit. For internal validation, we used leave-one-cohort-out cross-validation, whereby each of the eight North American cohorts alternatively served as a hold-out test set for a model fit to pooled data from the seven remaining cohorts. Predictions for each use of the eight cohorts as a test set were pooled for comparison to the PCPTRC. For external validation, we compared the PBCG model fit to all eight North American cohorts to the PCPTRC on data from all three European cohorts.

3. Results

We fit the PBCG model on 5992 biopsies from eight institutions in North America and validated it on 10 377 biopsies from three institutions in Europe. Descriptions of the pooled cohorts for fitting and validation are provided in Table 1 and by individual cohort in the Supplementary Appendix. Median age (approximately 65 yr) and PSA (approximately 6 ng/ml) were fairly consistent between cohorts. The rate of positive DRE varied from 13% in MSKCC to 51% in San Juan VA; the proportion of patients with African ancestry also varied, from <1% at European sites to 63% at the Durham VA. Prevalence of high-grade cancer ranged from 27% to 39%. Figure 1 shows the heterogeneity of prevalence of risk factors and their relationship to high-grade cancer outcome among the PBCG North American cohorts used to build the model, the PBCG European cohorts to validate it, and the PCPT population used to build the PCPTRC.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of the eight North American cohorts (5992 biopsies) used to build the models and three European cohorts (10 377 biopsies) used for external validation

| Eight North American centers to build model | Three European centers to validate model | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of biopsies | 5992 | 10 377 | |

| Age (yr), median (quartiles) | 64.7 (59;69) | 65.9 (60;70) | <0.0001 |

| PSA (ng/ml) | <0.0001 | ||

| Median (quartiles) | 6 (4.4;9) | 6.8 (4.8;10.6) | |

| ≤4, n (%) | 1098 (18) | 1683 (16) | |

| (4,20), n (%) | 4503 (75) | 7896 (76) | |

| >20, n (%) | 391 (7) | 798 (8) | |

| DRE result, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Normal | 3416 (57) | 7691 (74) | |

| Abnormal | 1698 (28) | 1645 (16) | |

| Unknown | 878 (15) | 1041 (10) | |

| 1st degree family history, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 4014 (67) | 5066 (49) | |

| Yes | 1095 (18) | 791 (8) | |

| Unknown | 883 (15) | 4520 (43) | |

| Race, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Black or African American | 780 (13) | 33 (0) | |

| Others | 4132 (69) | 5402 (52) | |

| Unknown | 1080 (18) | 4942 (48) | |

| Prior negative biopsy, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Yes | 1346 (22) | 1528 (15) | |

| No | 4612 (77) | 1749 (17) | |

| Unknown | 34 (1) | 7100 (68) | |

| Biopsy result, n (%) | 0.18 | ||

| Positive | 3009 (50) | 5324 (51) | |

| Negative | 2983 (50) | 5053 (49) | |

| Gleason score (of positive biopsies only), n (%) | 0.007 | ||

| <=6 | 1063 (35) | 1873 (35) | |

| 7 | 1366 (46) | 2279 (43) | |

| >=8 | 580 (19) | 1172 (22) | |

| Number of cores, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Median (quartiles) | 12 (12;14) | 10 (9;12) | |

| Unknown | 1297 (22) | 261 (3) | |

DRE = digital rectal exam; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Fig. 1.

Baseline demographics and univariate odds ratios for association between risk factor and high-grade cancer by cohort. Data not shown for African ancestry for Hamburg, Zurich, San Raffaele, Mayo Clinic, and UCSF. No prior negative biopsy for Hamburg and family history for UCSF because numbers were too low to reliably estimate the odds ratios.

DRE = digital rectal exam; MSKCC = Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; PCPT = Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; UCSF = University of California San Francisco; VA = Veterans Affairs.

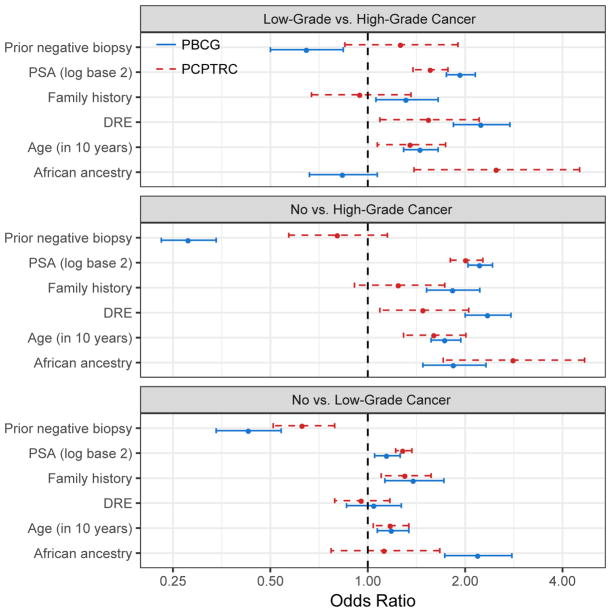

Results from fitting the PBCG model compared to the PCPTRC model are shown in Figure 2 in terms of odds ratios for comparison of all pairs of three outcomes: high- versus low-grade cancer, high-grade versus no cancer, and low-grade versus no cancer, with further data in the Supplementary Appendix. Coefficients are broadly similar for PSA and age but higher in the PBCG for family history and DRE and lower in the PBCG for prior negative biopsy. In the case of race, both studies found higher risk for African Americans. However, the PCPT but not the PBCG found that race distinguished high- from low-grade cancer, whereas the opposite was true for the comparison of low-grade to benign biopsy findings.

Fig. 2.

Odds ratios (in favor of endpoint listed to right over left) with 95% confidence intervals for the PBCG and PCPTRC multinomial logistic regression models.

DRE = digital rectal exam; PBCG = Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group; PCPTRC = Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

We compared the PBCG model to the PCPTRC for predicting risk of high-grade disease versus the two other outcomes combined (low-grade and no cancer) using both internal leave-one-out cross-validation on the 5992 biopsies used to build the PBCG model and external validation using 10 377 biopsies from the three European cohorts not used in constructing the PBCG model. The AUC of the PBCG model on internal validation was 75.5% (confidence interval [CI]: 74.2–76.8) compared to 72.3% (CI: 70.9–73.7) for the PCPTRC (p < 0.0001). For external validation, AUCs were 72.9% (CI: 71.8–73.9) and 69.7% (CI: 68.7–70.8), respectively, (p < 0.0001).

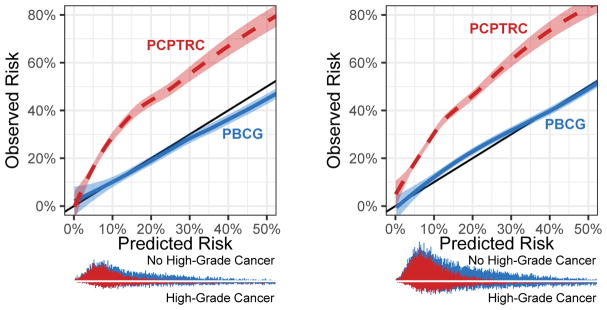

The PBCG model was well-calibrated. High-grade cancer risk was somewhat overestimated in the clinically irrelevant 30–50% range on internal validation; on external validation, the model slightly underestimated risk in the range 10–30% (Fig. 3). Comparatively, the PCPTRC underestimated risks up to nearly 20% across all thresholds on both data sets.

Fig. 3.

Calibration plot showing predicted versus observed risks for the PBCG risk model for high-grade cancer compared to the PCPTRC. Stacked histograms (PBCG on top of PCPTRC) showing distributions of risks from the two models are shown at the bottom. (A) North American cohorts. (B) External validation on European cohorts. PBCG = Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group; PCPTRC = Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator.

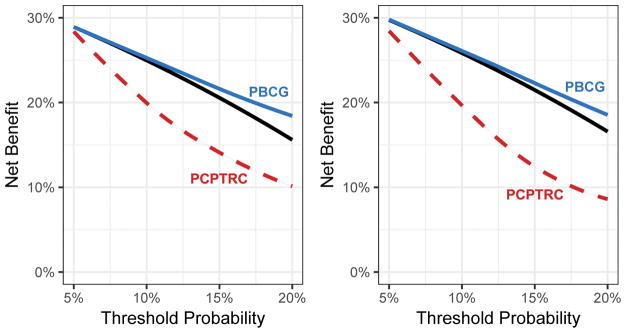

For clinical decision-making, both on internal and external validation, use of the PBCG model had superior net benefit to the strategy of “biopsy all patients” at thresholds starting above about 10%, and both of these strategies had superior net benefit to the PCPTRC across all relevant thresholds (Fig. 4). To give a concrete example, on internal (external) validation, at a risk threshold of 10%, the difference in net benefit between the PBCG model and the strategy of sending all men to biopsy was 0.0027 (0.0024), equivalent to a strategy that resulted in conducting approximately 27 (24) fewer biopsies per 1000 patients without missing any high-grade cancers. Results for several single cohort analyses as well as for the endpoint of overall cancer are given in the Supplementary Appendix.

Fig. 4.

Net benefit curves comparing the PBCG model for high-grade risk to the PCPTRC and the strategy of referring to biopsy all men. (A) North American cohorts. (B) External validation on European cohorts.

PBCG = Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group; PCPTRC = Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator.

The validated PBCG risk tool is now available online at the Cleveland Clinic Risk Calculator library for individual patient counseling. To illustrate how it may be used in practice, consider first a 65-yr-old Caucasian with no prior negative biopsy, no family history of prostate cancer, a normal DRE, and a PSA of 5 ng/ml. For this patient, the PBCG risk tool would return a risk of high-grade prostate cancer of 22.9% and a low-grade risk of 21.2%, corresponding to an overall risk of 44.1% for prostate cancer. These risk estimates are considerably higher than those provided by the PCPTRC, which would return estimates of 7.2%, 19.3%, and 26.5%, respectively. Now consider a second patient, a 55-yr-old African American, with other characteristics the same as the first patient. The PBCG would assign this patient a 20.4% risk of high-grade disease, 32.8% of low-grade disease, corresponding to an overall 53.2% overall risk of cancer, compared to the PCPTRC at 12.1%, 17.6%, and 29.7%, respectively. Risk curves for PSA values <10 for both of these patients are shown in the Supplementary Appendix.

4. Discussion

The foundation of the North American PBCG risk tool on contemporary North American biopsy patients contrasts that of the PCPTRC, which was built on a healthy predominantly Caucasian population (the PCPT required a PSA ≤4 ng/ml and normal DRE at entry and screened men annually up to 7 yr after) with a required end of study biopsy for all participants regardless of PSA level. One corollary is that only 10% of the PCPT population used to build the PCPTRC had PSA >4 ng/ml; this number exceeded 60% for each of the PBCG cohorts used to build the PBCG model. In addition to a population change, the switch in clinical practice from the six-core biopsy procedure used in the PCPTRC to the predominantly 12 cores used today and in the PBCG cohorts likely explains the under-prediction of the PCPTRC. Previous studies, including those within the PCPT, have confirmed the association of more biopsy cores with higher rates of detected prostate cancer [8,17]. Changes in the way in which pathologists grade prostate cancer have increased the prevalence of high-grade disease in contemporary cohorts [18,19]. Changing recommendations have also encouraged urologists to become more selective about biopsy, generally ordering a repeat PSA and assessing the likelihood of a benign cause for a PSA elevation. As such methods remove from the denominator a group of men at lower risk, this has the effect of increasing the prevalence of high-grade cancer at a given PSA level for men undergoing biopsy [20]. This explains why the PBCG gives a greater risk of cancer for a given PSA than the PCTPRC.

In addition to changes in the prevalence, many of the coefficients for prostate cancer risk factors differed between the PBCG and PCPTRC models, which may also be linked to changes in clinical practice. DREs in the current study were more likely to be undertaken by academic urologists specializing in prostate cancer rather than by general urologists, which may have contributed to the higher association between positive DRE and high-grade disease risk observed in this study. A prior negative biopsy will reduce risk more in an era where biopsy is more complete (more cores), leading to a greater reduction in the odds ratio. With respect to family history, the likelihood that family history will be noted in a clinical record is plausibly related to disease aggressiveness; for instance, prostate cancer in a family member may only be noted if it led to death or occurred at a young age. This stands in contrast to the PCPT clinical trial population where family history was a required data element from all participants, leading to the higher odds ratio for family history in this study. Odds ratios for the association of African American race to high-grade disease risk tended to be lower in this study compared to the PCPTRC, where they were not well-estimated due to the small number of African Americans included, as well as the low incidence of high-grade disease observed in a heavily screened study. They fall more in line with a recent study high-powered for this risk group [21].

There are several limitations to the study. The first is that despite a prospectively designed protocol, there were missing data for some six risk factors. For example, DRE was missing on 43% of MSKCC and 33% of Durham VA, race on 47% of Sunnybrook, and family history on 44% of San Juan VA and 100% of UCSF (Supplementary Appendix). Separate analyses with data not shown demonstrated that results did not differ much with multiple imputation for the missing data, and the online risk tool allows for missing values for some of the input variables. However, the imputation analyses assume the data are missing at random and would not cover a biased missing data mechanism. As motivated in the Patients and Methods section, the high-grade endpoint of Gleason score ≥7 is used, future work will investigate other definitions of significant disease, some that include the number of positive cores. Also in line with the PCPTRC, the new tool does not incorporate prostate volume as it is seldom collected prior to biopsy; however, future work will consider the impact of this risk factor. Additionally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) markers and biopsies were not collected as part of the primary protocol, but a small set of centers have contributed these to the PBCG and will be reported in future work. As the study cohort comprises men who have primarily undergone a standard 10–12 core prostate biopsy, the risk tool may not be well-calibrated for MRI-guided biopsies.

5. Conclusions

We have developed an online prostate cancer risk calculator based on multiple, contemporary biopsy cohorts with better performance characteristics compared to one of the currently most widely used online tools, the PCPTRC.

Take Home Message.

A North American multi-cohort-based risk tool for predicting prostate cancer outcomes on biopsy has been developed and outperformed a leading North American risk tool in validation. It is now available online for patients and their providers.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: This material is based upon work supported by the Research and Development Service, Urology Section, Department of Surgery and Department of Veterans Affairs, Caribbean Healthcare System San Juan, P.R. [LG]; Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense. [MAL]

CA179115 [All], P50-CA92629, P30-CA008748 [AJV], W81XWH-15-1-0441 [MAL], P30 CA054174 [RJL], K24 – CA160653 [SJF].

Footnotes

Author contributions: Donna P. Ankerst had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Ankerst, Vickers, Vertosick.

Acquisition of data: Guerrios, De Hoedt, Hernandez, Liss, Leach, Freedland, Kattan, Nam, Haese, Montorsi, Boorjian, Cooperberg, Poyet.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Ankerst, Vertosick.

Drafting of the manuscript: Ankerst, Vickers, Vertosick.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Ankerst, Vickers, Guerrios, De Hoedt, Hernandez, Liss, Leach, Freedland, Kattan, Nam, Haese, Montorsi, Boorjian, Cooperberg, Poyet.

Statistical analysis: Straubinger, Selig.

Obtaining funding: Ankerst, Vickers.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Leach, Vertosick.

Supervision: Leach.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: Donna P. Ankerst certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Borghese M, Ahmed H, Nam R, et al. Complications after systematic, random and image-guided prostate biopsy. Eur Urol. 2017;71:353–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liss MA, Ehdaie B, Loeb S, et al. An update of the American Urological Association White Paper on the prevention and treatment of the more common complications related to prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2017;198:329–34. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.01.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline. Part I: Risk stratification, shared decision making, and care options. J Urol. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Kranse R, Roobol M, Schröder FH. A graphical device to represent the outcomes of a logistic regression analysis. Prostate. 2008;68:1674–80. doi: 10.1002/pros.20840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson IM, Jr, Leach RJ, Ankerst DP. Focusing PSA testing on detection of high-risk prostate cancers by incorporating patient preferences into decision making. JAMA. 2014;312:995–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:215–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ankerst DP, Till C, Boeck A, et al. The impact of prostate volume, number of biopsy cores and American Urological Association symptom score on the sensitivity of cancer detection using the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator. J Urol. 2013;190:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.12.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB, et al. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma: Definition of grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:244–52. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Roobol MJ, et al. The relationship between prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer risk: the Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4374–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ankerst DP, Boeck A, Freedland SJ, et al. Evaluating the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial High Grade Prostate Cancer Risk Calculator in 10 international biopsy cohorts: results from the Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group. World J Urol. 2014;32:185–91. doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0869-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roobol MJ, Schröder FH, Hugosson J, et al. Importance of prostate volume in the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) risk calculators: results from the prostate biopsy collaborative group. World J Urol. 2012;30:149–55. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0804-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ankerst DP, Hoefler J, Bock S, et al. Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator 2. 0 for the prediction of low- vs high-grade prostate cancer. Urology. 2014;83:1362–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroem P, Nordstroem T, Groenberg H, Eklund M. The Stockholm-3 model for prostate cancer detection: Algorithm update, biomarker contribution, and reflex test potential. Eur Urol. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.12.028. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Alberts AR, Schoots IG, Bokhorst LP, et al. Characteristics of prostate cancer found at fifth screening in the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer Rotterdam: can we selectively detect high-grade prostate cancer with upfront multivariable risk stratification and magnetic resonance imaging? Eur Urol. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.06.019. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lin DW, Newcomb LF, Brown MD, et al. Evaluating the four kallikrein panel of the 4Kscore for prediction of high-grade prostate cancer in men in the Canary Prostate Active Surveillance Study. Eur Urol. 2017;72:448–54. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ankerst DP, Till C, Boeck A, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Thompson IM. Predicting risk of prostate cancer in men receiving finasteride: effect of prostate volume, number of biopsy cores, and American Urological Association symptom score. Urology. 2013;82:1076–81. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Mehta SS, Carroll PR CaPSURE. Time trends in clinical risk stratification for prostate cancer: implications for outcomes (data from CaPSURE) J Urol. 2003;170:S21–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000095025.03331.c6. discussion S26-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danneman D, Drevin L, Robinson D, Stattin P, Egevad L. Gleason inflation 1998–2011: a registry study of 97,168 men. BJU Int. 2015;115:248–55. doi: 10.1111/bju.12671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eapen RS, Herlemann A, Washington SL, 3rd, Cooperberg MR. Impact of the United States Preventive Services Task Force 'D' recommendation on prostate cancer screening and staging. Curr Opin Urol. 2017;27:205–9. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Punnen S, Freedland SJ, Polascik TJ, et al. A multi-institutional prospective trial in the Veterans Affairs Health System confirms the 4Kscore maintains its predictive value among African American men. J Urol. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.113. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]