Abstract

Background

The design of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) health insurance marketplaces influences complex health plan choices.

Objective

To compare the choice environments of the public health insurance exchanges in the fourth (OEP4) versus third (OEP3) open enrollment period and to examine online marketplace run by private companies, including a total cost estimate comparison.

Design

In November–December 2016, we examined the public and private online health insurance exchanges. We navigated each site for “real-shopping” (personal information required) and “window-shopping” (no required personal information).

Participants

Public (n = 13; 12 state-based marketplaces and HealthCare.gov) and private (n = 23) online health insurance exchanges.

Main Measures

Features included consumer decision aids (e.g., total cost estimators, provider lookups) and plan display (e.g., order of plans). We examined private health insurance exchanges for notable features (i.e., those not found on public exchanges) and compared the total cost estimates on public versus private exchanges for a standardized consumer.

Results

Nearly all studied consumer decision aids saw increased deployment in the public marketplaces in OEP4 compared to OEP3. Over half of the public exchanges (n = 7 of 13) had total cost estimators (versus 5 of 14 in OEP3) in window-shopping and integrated provider lookups (window-shopping: 7; real-shopping: 8). The most common default plan orders were by premium or total cost estimate. Notable features on private health insurance exchanges were unique data presentation (e.g., infographics) and further personalized shopping (e.g., recommended plan flags). Health plan total cost estimates varied substantially between the public and private exchanges (average difference $1526).

Conclusions

The ACA’s public health insurance exchanges offered more tools in OEP4 to help consumers select a plan. While private health insurance exchanges presented notable features, the total cost estimates for a standardized consumer varied widely on public versus private exchanges.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-018-4483-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: health insurance marketplace, Affordable Care Act, consumerism, health insurance, decision support

More than 12 million Americans selected a health insurance plan on the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) public marketplaces in fourth open enrollment period (OEP4; November 2016–January 2017).1 However, consumers have a hard time choosing health insurance plans because of the number and complexity of plan options, limited health insurance literacy, and lack of information.2–4 Sometimes consumers forgo insurance enrollment all together if too overwhelmed.5

Consumers’ insurance choices strongly influence how they access (or are unable to access) high-quality health care, particularly in the primary and inpatient care settings. To understand the true cost of a health insurance plan, consumers must calculate often complicated cost sharing values (e.g., deductibles and coinsurance) to estimate out-of-pocket spending. As a result, cost-conscious but overwhelmed consumers may overly focus on monthly premiums with suboptimal plan choices.6 Similarly, as insurers use narrow provider networks to control costs, consumers need to know if their preferred providers are covered in their selected plan.7 Choice errors carry substantial financial consequences, as cost sharing rises and out-of-network costs are often not subject to out-of-pocket maximums (meaning that consumers bear even more financial risk).

The design of the online health insurance marketplaces influences complex health plan choices.6, 8 Our prior work has demonstrated that the public ACA marketplaces have offered various tools in prior open enrollment periods (OEPs) to help consumers make informed health plan choices.9, 10 Total cost estimators, for example, are tools that can help consumers estimate their yearly total out-of-pocket spending on healthcare—by predicting the amount of cost sharing (based on expected healthcare utilization), adding it to the monthly premium, and subtracting any subsidy discounts. While most exchange officials see the value in providing these tools, no consensus exists on the best way to structure the estimators, nor has their accuracy been tested.11

Health policy reforms could make the design of the marketplace choice environments even more important if consumers are offered more diverse plan options in a less regulated health insurance market (e.g., repeal of universal coverage for essential health benefits or pre-existing conditions) and where consumers with more “skin-in-the-game” are exposed to higher costs.12, 13 In this study, we build on our prior work by presenting new data on the choice environments of the state-based marketplaces and HealthCare.gov in OEP4. We compare OEP4 to data previously collected from the third open enrollment period (OEP3), as we have seen an evolution in the health insurance exchanges over time .10, 14 We also add an examination of the choice environment on privately run health insurance marketplaces. These privately run health insurance exchanges are similar to the public exchanges in that they are a “one-stop shopping” site for a variety of health plans; however, they are developed and operated by private companies, rather than by the federal or state government. Current policy debates (e.g., selling health plans across state lines, employers forming Association Health Plans, full repeal of the ACA) could lead to increased opportunities for privately run exchange websites to enter the health insurance shopping landscape.13

METHODS

Data Collection

We collected data in November–December 2016 during OEP4 from the federal and all 12 state-based marketplaces established by the ACA (Appendix Table 5). We navigated each site as a typical marketplace shopper in two contexts: “window-shopping” allows consumers to browse plans and prices without creating an account or entering detailed personal information, while “real-shopping” requires a consumer account and personal information. We collected data in both contexts because real and window-shopping have differed in prior OEPs, potentially due to the use of different vendors for each context.9, 10 We compared data from OEP4 to data previously collected using similar procedures during OEP3 in November 2015.9

Table 5.

Reviewed Online Health Insurance Exchanges

| Public exchanges | |

| HealthCare.gov | |

| Covered California | |

| Connect for Health Colorado | |

| Access Health CT | |

| DC Health Link | |

| Your Health Idaho | |

| Maryland Health Connector | |

| Massachusetts Health Connector | |

| MNsure | |

| NY State of Health | |

| HealthSource RI | |

| Vermont Health Connect | |

| Washington Health Plan Finder | |

| Private exchanges | |

| Choice Health Insurance | |

| Stride Health | |

| GoHealth | |

| Healthsherpa | |

| HoneyInsured Insurance Services | |

| GetInsured | |

| ValuePenguin Inc. | |

| HealthPocket | |

| Consumer’s Checkbook | |

| Access Health Insurance INC | |

| Access Medical Health Group | |

| AXS Health Insurance Agency | |

| Benefinder | |

| Ehealth insurance services | |

| Freedom health | |

| Health Insurance | |

| Healthcompare insurance services | |

| JLBG Health | |

| Mintco Financial | |

| Navinsure | |

| TFA Benefits | |

| TrueCoverage LLC | |

| Welltheos |

We also surveyed privately run online health insurance exchanges in November–December 2016 for notable features, defined as choice architecture elements not found on the public exchanges, and total cost estimators. From a list of federally approved brokers15 and RAND-reviewed sites,16 we identified 23 private online exchanges that, like public online marketplaces, sold multiple private health plans without requiring email or phone communication (Appendix Table 5). These web-brokers completed the registration requirements for the federally facilitated marketplace and listed any on-exchange plans for the same prices as public exchange offerings. Some private online exchanges operated in geographically restricted areas.

We determined that total cost estimators for OEP4 plans were available on seven public exchanges (six state-based marketplaces, HealthCare.gov) and two of 23 federally approved private online exchanges (Stride Health, GoHealth). HoneyInsured had a total cost estimator but had not been updated for OEP4 plans, precluding price comparisons. We window-shopped on these nine exchanges as a standardized consumer with common medical conditions: a 30-year-old single male with $25,000 annual income, with type II diabetes and asthma on metformin and albuterol, with an average of four doctor visits per year and no expected medical procedures, and in “good” health.

Outcomes

We documented plan display characteristics, including default order of plans and plan features presented. We compared our findings to the choice environment features previously documented in OEP3, which were selected based on their known availability in prior enrollment periods and potential impact on health plan choice.10, 17

New data elements captured in OEP4 were how consumers could transition between window- and real-shopping platforms and whether exchanges offered a mobile application. Because our prior research illustrated substantial differences in window- and real-shopping and the transition was noted to be cumbersome, we documented if consumers were supported in moving from the browsing window-shopping environment to the real-shopping environment where they purchased plans, such as with an online shopping cart. We additionally searched for health insurance exchange mobile applications as consumers increasingly shop on their mobile devices.18

For the comparison of total cost estimators, we documented estimator inputs (i.e., questions used to generate estimates and descriptions for levels of healthcare utilization) and estimator outputs (i.e., total cost estimates for a particular silver-level plan and for different levels of healthcare utilization) on each of the nine exchanges with an estimator.

For data collection on both private and public exchange websites, all features were surveyed with screenshots and/or screen video-capture documentation by at least two researchers who worked independently. Any coding discrepancy was resolved by team consensus. This study was deemed exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

RESULTS

Public Health Insurance Exchanges

Consumer Decision Aids

Compared to OEP3, the public marketplaces increased use of nearly all studied consumer decision aids in OEP4 (Table 1). Exchange-specific choice environment details for OEP4 appear in Appendix Table 6. In window-shopping, we found total cost estimators on over half (n = 7 of 13) of the public exchanges versus five of 14 in OEP3. In the District of Columbia, Minnesota, and Vermont, consumers could both sort and filter health plans by total cost estimate, while the rest allowed either sorting or filtering. Idaho displayed flags, such as “low” or “average” to indicate the “expense estimate” without a specific estimate. In real-shopping, only California and HealthCare.gov had total cost estimators.

Table 1.

Choice Environment in the Health Insurance Marketplaces, Fourth Open Enrollment Period, Window-Shopping

| Consumer decision aid | Description |

|---|---|

| Total cost estimator | Personalized estimate of how much a shopper will pay out-of-pocket for the health plan. Includes monthly premiums, deductibles, coinsurance, and copays |

| Integrated provider lookup* | Enables shopper to lookup providers by name and filter health plans by those that cover the provider |

| Integrated drug lookup* | Allows shopper to lookup drugs by name and filter health plans by those that cover the specific drug |

| Quality ratings | Organizes plans by quality, which is typically based on patient experience or review by an accredited agency |

| Pop-up definitions | Explanations that appear when the cursor hovers over a key term |

| Choice tool | Additional sets of questions to further narrow health plan options |

| Discounted premium shown | An estimate of the premium for the health plan after tax subsidy is applied |

| Cost sharing reduction nudge | Prompt to shoppers with incomes less than 250% Federal Poverty Level to choose a silver tier health plan to receive extra savings on deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments |

*Websites that directed the consumer to another website or an external file were not classified as having an integrated decision aid

Table 6.

Choice Environment in Fourth Open Enrollment Period

| Window-shopping | Real-shopping | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Availability on HealthCare.gov | Availability on SBMs (N = 12) | Availability on HealthCare.gov | Availability on SBMs (N = 12) | |||

| Consumer decision aids | ||||||

| Total cost estimator | Yes | 6 | CA, CO, CT, DC, MN, VT | Yes | 1 | CA |

| Integrated provider lookup | Yes | 6 | CO, DC, MD, MA, RI, WA | Yes | 7 | CO, DC, MD, MA, NY, RI, WA |

| Integrated drug lookup | Yes | 2 | CO, DC | Yes | 0 | |

| Quality ratings | No | 6 | CA, CO, CT, MD, NY, WA | No | 8 | CA, CO, CT, MD, NY, RI, VT, WA |

| Pop-up definitions | Yes | 12 | CA, CO, CT, DC, ID, MD, MA, MN, NY, RI, VT, WA | Yes | 12 | CA, CO, CT, DC, ID, MD, MA, MN, NY, RI, VT, WA |

| Choice tool | No | 3 | CT, RI, WA | No | 3 | CO, RI, WA |

| Discounted premium shown | Yes | 11 | CA, CO, CT, DC, ID, MD, MN, NY, RI, VT, WA | –† | –† | –† |

| Cost sharing reduction nudge | Yes | 10 | CA, CO, CT, ID, MD, MN, NY, RI, VT, WA | –† | –† | –† |

| Default order of plans | ||||||

| Premium | Yes | 3 | ID, NY, MA* | Yes | 7 | CO, CT, ID, MD, RI, VT, WA |

| Estimated total OOP cost | No | 5 | CA, CO, DC, MN, VT | No | 1 | CA |

| Best fit for consumer | No | 1 | MN | No | 1 | MN |

| Silver listed first | Yes* | 3 | MD, RI, WA | No | 1 | MA |

| Standard plans listed first | No | 0 | No | 1 | DC | |

| Metal level | No | 0 | No | 1 | NY (bronze listed first) | |

Authors’ analysis of health insurance marketplaces in the fourth open enrollment period, November–December 2016

OOP out-of-pocket, SBM state-based marketplace

*Initial filter (before viewing plan options) highlights “SEE ALL SILVER PLANS” over “See all plans”

†Unable to shop as a consumer qualifying for a discounted premium or cost sharing reduction in real-shopping

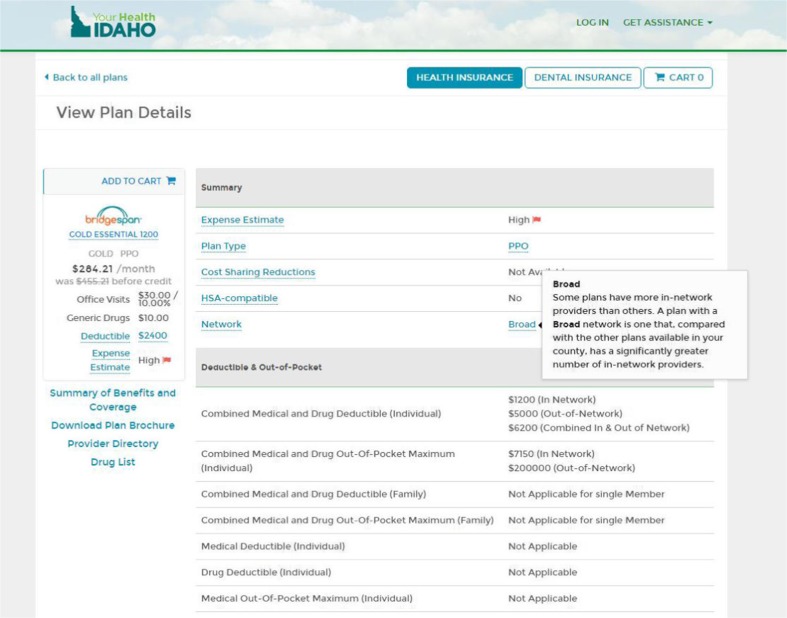

All sites with integrated provider lookups in OEP3 maintained them in OEP4 (window-shopping, seven; real-shopping, eight). Twice as many marketplaces included an indication of network size (n = 4 of 13 versus 2 of 14). Massachusetts used flags for health plans with a narrow network; the District of Columbia provided a list of in-network hospitals; New York provided a percent of nearby hospitals and providers that were covered; and Idaho used labels basic, standard, or broad for network size relative to other plans available in the county (for an example of a network size indicator, see Appendix Fig. 2). In window-shopping, the District of Columbia added an integrated drug lookup in OEP4, joining the HealthCare.gov and Colorado from OEP3. Only HealthCare.gov had an integrated drug lookup in real-shopping.

Fig. 2.

Network size indicator on Your Health Idaho.

Quality ratings were more prevalent in OEP4 (n = 6 of 13 versus 4 of 14). For the first time, pop-up definitions that appeared when hovering a cursor over key health insurance terms (e.g., deductible) were available on all exchanges in both shopping contexts. For consumers qualifying for health plan discount programs, 11 of 13 public exchanges indicated that consumers who qualify for a cost sharing reduction (i.e., reduction in deductible, copay, and coinsurance amounts) should consider silver plans because the savings are only available within the silver tier.

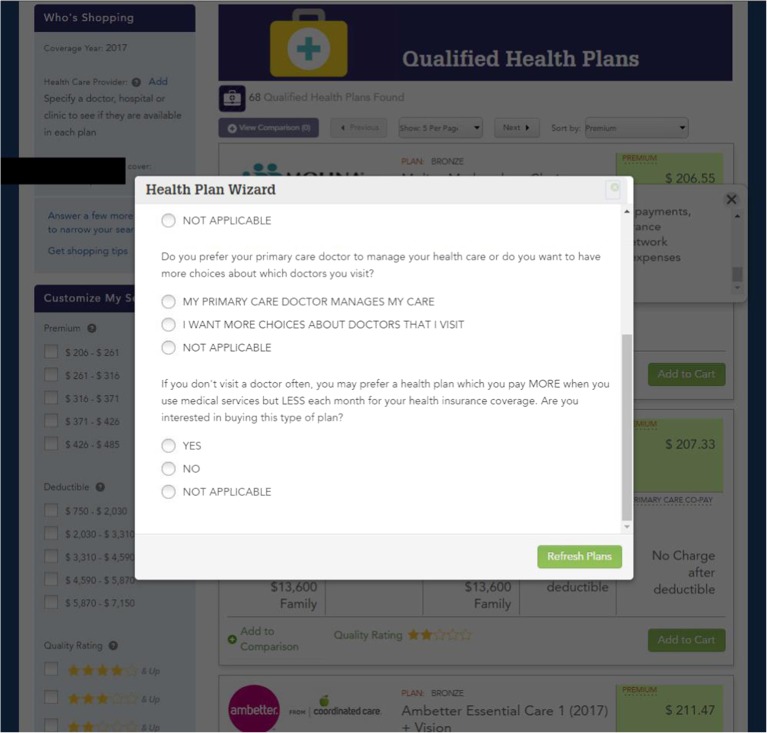

Choice tools on four of 13 sites allowed consumers to narrow their plan options based on their responses to a series of questions. For example, Washington state’s tool asked, “Do you prefer your primary care doctor to manage your health care or do you want to have more choices about which doctors you visit?” to filter by HMO or PPO plans (for an image of the choice tool, see Appendix Fig. 3). Colorado’s choice tool was a series of five filters for preferred provider, premium range, deductible range, metal tier level, and insurance carrier. Each page offered further education; for example, “Plans with the higher deductibles usually have lower premiums and higher out-of-pocket costs at the time you receive services or obtain medications...” Rhode Island asked a series of three questions on frequency of medical use, chronic illness, and payment preferences to reorder plans.

Fig. 3.

Choice Tool “Health Plan Wizard” in Washington State.

Plan Display Characteristics

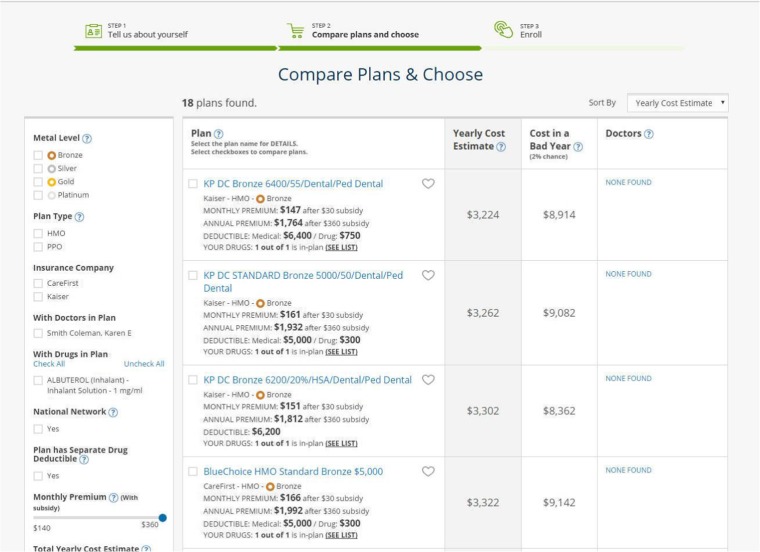

The most common default plan orders were total cost estimate and premium (Table 2; for an example of plans ordered by total cost estimate, see Appendix Fig. 4). Plan order could differ between window- and real-shopping for the same state. In window-shopping, 5 of 13 sites ordered plans by estimated total out-of-pocket costs. In real-shopping, eight state-based marketplaces ordered plans by premium. Other orders used were best fit for consumer, silver listed first for consumers who qualified for a cost-sharing reduction, standard plans listed first, or metal tier.

Table 2.

Public Exchange Choice Environment in Fourth Versus Third Open Enrollment Period

| Window-shopping | Real-shopping | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC.gov | SBMs | HC.gov | SBMs | |||||

| OEP4 | OEP3 | OEP4 (n = 12) | OEP3 (n = 13) | OEP4 | OEP3 | OEP4 (n = 12) | OEP3 (n = 13) | |

| Consumer decision aids | ||||||||

| Total cost estimator | Yes | Yes | 6 | 4 | Yes | No | 1 | 2 |

| Provider lookup | Yes | Yes | 6 | 7 | Yes | Yes | 7 | 8 |

| Drug lookup | Yes | Yes | 2 | 1 | Yes | No | 0 | 0 |

| Quality ratings | No | No | 6 | 4 | No | No | 8 | 5 |

| Pop-up definitions | Yes | Yes | 12 | 9 | Yes | No | 12 | 11 |

| Default order | ||||||||

| Premium | Yes | Yes | 3 | 10 | Yes | Yes | 7 | 9 |

| Estimated total OOP cost | No | No | 5 | 2 | No | No | 1 | 2 |

| Best fit for consumer | No | No | 1 | 0 | No | No | 1 | 1 |

| Silver plans first | Yes* | No | 3 | 3 | No | No | 1 | 1 |

| Standard plans first | No | No | 0 | 0 | No | No | 1 | 0 |

| Metal tier | No | No | 0 | 1 | No | No | 1 | 0 |

“Window-shopping” did not require an account or detailed personal information, while “real-shopping” required a consumer account and personal information

OEP4 Fourth Open Enrollment Period, OEP3 Third Open Enrollment Period, OOP out-of-pocket, HC.gov HealthCare.gov, SBM state-based marketplace

*Initial filter (before viewing plan options) highlights “SEE ALL SILVER PLANS” over “See all plans”

Fig. 4.

Health plans listed in order of yearly total cost estimate.

Three sites (California, Idaho, Washington) provided an online shopping cart to transition from window- to real-shopping. Three public health insurance exchanges had mobile applications (Connecticut, Maryland, DC).

Private Online Health Insurance Exchange Notable Features

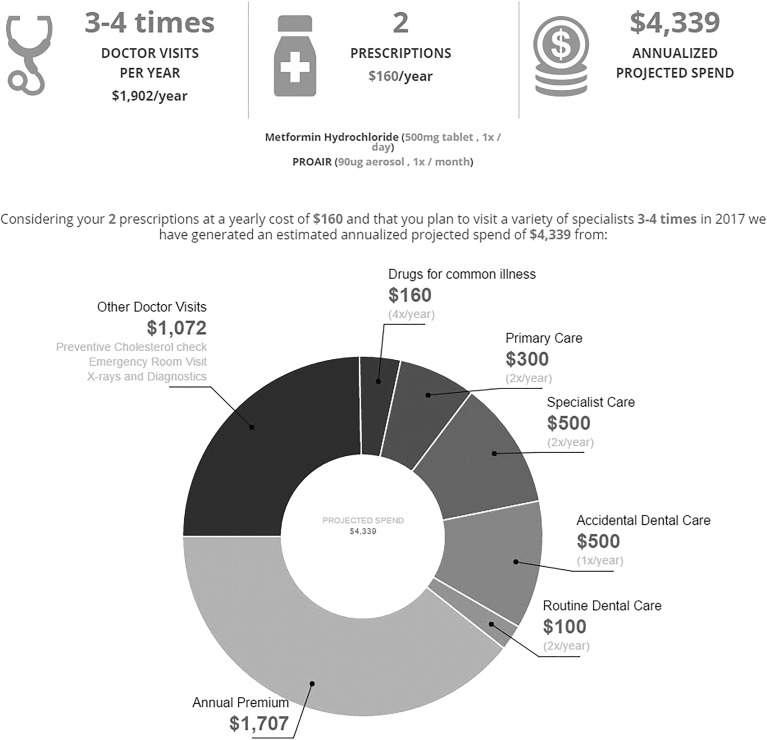

Private online exchanges offered several notable features for total cost estimators (Table 3). Stride Health and HoneyInsured indicated out-of-pocket estimates for specific conditions (e.g., concussion). GoHealth provided an infographic representation of the total cost estimate (Fig. 1). HoneyInsured asked a unique question to generate its estimate: “How much do you expect to spend on healthcare if you didn’t have insurance next year?”

Table 3.

Notable Features on Private Online Exchange Websites

| Domain | Feature | Private exchange |

|---|---|---|

| Total cost estimator | Graphic representation of cost estimate components | • GoHealth |

| Estimates for specific scenarios (e.g., concussion) |

• Stride Health • HoneyInsured |

|

| Unique input question | • HoneyInsured | |

| Personalized plan display | Recommended plan |

• eHealthInsurance • GoHealth • Stride Health • HoneyInsured |

| Plan partitioning* |

• HoneyInsured • Stride Health |

|

| Personalized plan score |

• GetInsured • ValuePenguin |

|

| Network transparency | Map of in-network providers | • HealthSherpa |

*Plan partitioning refers to highlighting certain health plays by displaying them separately

Fig. 1.

Infographic for total cost estimator on GoHealth. Source: GoHealth ( www.gohealthinsurance.com ).

Private exchanges personalized plan display and highlighted recommended plans in notable ways. Examples included identifying a recommended plan; presenting only recommended plans; or using flags such as “best match,” “runner-up,” “hand-picked plans,” or “cheap plans.” HoneyInsured and Stride Health featured plan partitioning, which highlighted certain plans by displaying them separately. GetInsured provided a plan score based on shopper preferences. HealthSherpa provided a map of in-network providers for each health plan. A video illustrating notable features on plan recommendation and costs for specific conditions is available online (Online Video in Appendix).

ESM 1.

Private Online Health Insurance Exchange Notable Features Example Source: Stride Health (www.stridehealth.com). Stride Health provided a plan recommendation and out-of-pocket costs for specific conditions in their choice environment, which were notable features not seen on the public insurance marketplaces. (MP4 29746 kb)

Total Cost Estimators

The total cost estimates for the same plan by state for our standardized consumer varied substantially between the public and private exchanges (Table 4). The total cost estimate for a Pennsylvania plan sold on HealthCare.gov was $1905 versus approximately $3900 on the private exchanges. The Connecticut state-based marketplace total cost estimate ($6352) was higher than on the private exchanges ($4792, $4286). The average difference between public and private exchange estimates for the same plan in each state was $1526.

Table 4.

Health Insurance Plan Total Cost Estimates* for a Standardized Consumer† Considering the Same Plan By State: Comparison of Estimates Between Public and Private Online Exchanges

| Public exchange‡ (zip code) | Public exchange estimate input criteria | Public exchange estimate | Stride health§ estimate | GoHealth|| estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HealthCare.gov (19104) | Healthcare use (low, med, high) | $1905 | $3919 | $3950 |

| California (94610) |

Healthcare use (low, med, high, very high) Prescription use (low, med, high, very high) |

$2444.22 | $3769 | $4339 |

| Colorado (80204) | Healthcare use (low, med, high) | $2630 | $4344 | $4188 |

| Connecticut (06602) |

Conditions (e.g., asthma) Condition severity (low, moderate, high) Surgeries (e.g., back surgery) |

$6352.36 | $4286 | $4792 |

| Washington DC (20011) | Level of health (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), expected medical procedures (e.g., angioplasty) | $4098 | $4660 | No total cost estimates in DC area |

| Minnesota (55405) | Level of health (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), expected medical procedures (e.g., angioplasty) | $3252 | $4136 | Did not sell plans in state |

| Vermont (05402) | Level of health (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), expected medical procedures (e.g., angioplasty) | $2619 | $3791 | Did not sell plans in state |

*Total cost estimates sum the monthly premium with expected cost sharing minus any subsidies. Estimates are shown for the same plan within each state. Pennsylvania was selected as a representative state for HealthCare.gov.

†Standardized consumer: 30-year-old single male with $25,000 annual income; with type II diabetes and asthma on two chronic medications, metformin and an albuterol inhaler; with an average of four doctor visits per year and no expected medical procedures; and in good/average health

‡Data presented on all public exchanges with a total cost estimate feature on their websites

§Stride Health estimate input criteria: prescription drugs (specifics—dose, frequency). Medical conditions (none, diabetes, arthritis, depression, ADHD, high cholesterol, asthma, heart disease, high blood pressure, COPD)

||GoHealth estimate input criteria: number of doctor visits (1–2 times, 3–4, 5–11, or 12+ times) and medication entry

Differences in cost estimates may be attributable, in part, to differences in the number and specificity of questions asked to calculate the estimate (Table 4) and the response categories available to consumers (Appendix Table 7). Questions included categorizing medical care and prescription use, self-reported health status, existing medical conditions, expected medical treatments, and ongoing prescriptions. Answer options differed; the lowest healthcare utilization option on HealthCare.gov was described as “minimal other medical expense,” versus “1-2 doctor visits” in California, and “4 doctors’ visits” in Colorado. Distinct utilization categories and estimate algorithms resulted in different distributions of cost estimates between the lowest and highest utilization categories for the same plan.

Table 7.

Categories of Healthcare Utilization Used to Generate Total Cost Estimates* on Public Health Insurance Exchanges

| Public exchange | Low | Medium | High | Very high |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HealthCare.gov | Minimal other medical expense |

2 doctor visits 1 lab/diagnostic test 2 Rx drugs Minimal other |

10 doctor visits 4 lab/diagnostic tests 17 Rx drugs $7600 other |

– |

| HealthCare.gov estimate† | $1705 | $1905 | $7410 | – |

| California (healthcare use) |

1–2 doctor visits Preventive care |

3–5 doctor visits 3–5 lab or X-ray 1 small outpatient treatment Often care is for ongoing health problem |

≥ 6 doctor visits Surgery, therapy, or treatment in outpatient center plus follow-up care |

Hospital stay High cost radiology scans or outpatient treatment ≥ 6 doctor visits with lab tests |

| California (prescription use) | 1–2 Rx during year for brief illness | 1 Rx/month for a health problem; may need several short-term meds | 2 Rx/month, often higher cost medications | ≥ 3 Rx/month for health problems or very high cost medications |

| California estimate† | $1892.84 | $2444.22 | $4035.86 | $7407.84 |

| Colorado |

4 doctor visits 0 outpatient visits 0 days in hospital Minimal other |

7 doctor visits 1 outpatient visits 0 days in hospital Minimal other |

13 doctor visits 1 outpatient visits 0 days in hospital Minimal other |

– |

| Colorado estimate† | $2630 | $3220 | $4400 | – |

| Connecticut |

≤ 2 PCP visits < 2 specialty visits Some generic Rx No outpatient or hospital services |

≥ 2 PCP visits ≥ 2 specialty visits Generic and brand Rx 1–2 outpatient services Single ER visit No hospitalization |

1–2 PCP visits ≥ 3 specialty visits 6+ brand and specialty Rx > 2 outpatient services Advanced radiology Multiple ER visits ≥ 1 hospitalization |

– |

| Connecticut estimate† | $6187.36 | $6352.36 | $6887.36 | – |

ER emergency room, PCP primary care physician, Rx prescription

*Total cost estimates sum the monthly premium with expected cost sharing minus any subsidies

†Total cost estimates are shown for the same silver-level plan within each state at each level of healthcare utilization. Pennsylvania was selected as a representative state for HealthCare.gov

DISCUSSION

The ACA’s public health insurance exchanges offered more consumer decision tools in OEP4 compared to OEP3. The increased decision support on the public exchanges is encouraging, as the complexity of selecting a plan has been clearly demonstrated and consumers may be asked to select from more diverse plan options.4, 13, 19 For the first time, we also examined the choice environment of private online health insurance exchanges, which provide alternate venues for consumers to shop for plans. These private exchanges offered notable consumer decision aid features that uniquely presented plan data or further personalized shopping for consumers.12

We also identified that the same health insurance plan considered by the same patient had widely varied total cost estimates on public and private exchanges. Theoretically, these estimates can help consumers identify the highest value health plans. However, the estimates are valuable only if accurate and understood by consumers. A substantial underestimate, for example, could have considerable financial consequences for a patient with a costly chronic condition, while an overestimate may deter a relatively low-cost patient from buying insurance. Notably, only 2 of 23 privately run exchanges, compared to 7 of 13 public exchanges offered a total cost estimator for plans in the fourth OEP.

HealthCare.gov was the only public marketplace to offer a total cost estimator, provider lookup, and drug lookup in both window- and real-shopping experiences. These tools have been cited as current gold standards of informed consumer choice.20 The federal exchange’s relative scale and budget may have allowed development of these tools in both shopping contexts.12

Provider lookups were again found on the majority of sites in OEP4. Improved transparency of insurance networks continues to be critically important as consumers are selecting among narrow network plans or plans with changing networks of providers.7 Choosing the wrong plan that excludes an existing primary or specialty provider can disrupt continuity of care or expose a patient to much higher out-of-network costs. While we found some indicators of overall network size (e.g., flags, descriptors, percentages of in-network providers), the narrowness of networks may differ for patients needing different specialty medical services, such as mental health or pediatric care.21, 22 Tools, such as the map of nearby primary and specialty in-network providers seen on one of the private exchanges, may better help patients assess the fit of a network for their own medical needs.

While integrated provider lookups were prominently featured on most sites, drug formularies and quality ratings were not. Prescription costs can account for substantial medical expenditures and are associated with medication non-adherence.23 Especially because Medicare.gov has long demonstrated the feasibility and importance of online drug formularies, it is surprising that more public exchanges do not include this feature.24 Quality ratings were also infrequently found. While five-star quality ratings can summarize health plan cost and quality information, no consensus exists on how to generate or explain them.16, 25 Improving the clinical relevance of these measures (e.g., specifying quality ratings if you are a patient with diabetes) could facilitate better health plan choices.

For the first time since the ACA public exchanges opened, less than half used premium as the default order in window-shopping and instead adopted recommendations to order plans by total cost estimate or best fit26. Expert groups have suggested listing plans by premium can cause consumers to focus on the premium and ignore sometimes substantial out-of-pocket costs.26 Moving beyond default plan ordering, several private exchanges more boldly made plan recommendations, either explicitly with a “recommended plan” flag or by highlighting certain plans by displaying them separately on the page. Private exchanges have more choice environment flexibility, as they are not constrained by the political pressures and public contracting procedures of state and federally run exchanges. Challenges to these recommendation tools include how to account for consumer preferences and willingness to trade-off costs for coverage, and identifying appropriate algorithms since research tends to focus on poor rather than optimal plan choices.16

While we describe choice environment features, we did not test the accuracy or impact of the tools on consumer choices. Well-designed tools may improve consumer shopping,8 while inaccurate or poorly explained tools could inadvertently lead to poor choices. We also may have missed certain choice environment features on the exchanges, though we have multiple years of experience shopping on these websites, so the features would likely not be obvious to a typical shopper. Finally, we surveyed the websites early in OEP4, similar to OEP3; the exchange websites may have been updated with new or different choice features after we completed our data collection.

While the future of the ACA and its marketplaces remain uncertain, understanding the construction and impact of the choice environments on health plan selection has implications for improving insurance choices more broadly. Public and privately run exchanges can learn from each other to develop choice environments that best support consumers in making difficult health plan selections. In addition, the decision-making process and tools on the ACA exchanges are relevant to consumers who are selecting among plan options for employer-sponsored or Medicare Advantage insurance.

Research is needed on the impact of different choice environment features. Key research questions include how current tools influence consumers’ plan choices in experimental and real-world settings and what data source and assumption differences lead to the variation in total costs estimates.27 For example, what degree of input specificity (e.g., simple classification as low or medium user, versus indicating specific conditions and medications) best predicts actual expenses? The diversity and evolution but overall similar structure of the ACA exchange choice environments present an opportunity to identify best practices and study the impact of the different tools in a natural experiment. As millions of patients are asked to be increasingly savvy health insurance consumers—facing potentially more diverse and less regulated health plan options—the next generation of online health insurance marketplaces are needed to facilitate access to the health care they want, at the lowest price.

Electronic supplementary material

Appendix

Contributors

None

Funding Information

Funding for this project was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Tom Baker is a co-founder of Picwell, Inc., a health information/technology company that leverages big data and predictive analytics to help consumers optimize health plan choice. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Prior Presentations

Presented as a poster at the AcademyHealth Research Meeting, June 2017 in New Orleans, Louisiana.

References

- 1.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Health insurance marketplaces 2017 open enrollment period final enrollment report: November 1, 2016-January 31, 2017 2017. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2017-Fact-Sheet-items/2017-03-15.html. Accessed 18 March 2018.

- 2.Politi MC, Kaphingst KA, Kreuter M, Shacham E, Lovell MC, McBride T. Knowledge of health insurance terminology and details among the uninsured. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;71(1):85-98. 10.1177/1077558713505327. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Wong CA, Asch DA, Vinoya CM, Ford CA, Baker T, Town R, et al. Seeing health insurance and HealthCare.gov through the eyes of young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(2):137-43. 10.1177/1077558713505327. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bhargava S, Loewenstein G. Choosing a health insurance plan: complexity and consequences. JAMA. 2015;314(23):2505–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyengar SS, Lepper MR. When choice is demotivating: can one desire too much of a good thing? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(6):995–1006. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ubel PA, Comerford DA, Johnson E.Healthcare.gov 3.0—behavioral economics and insurance exchanges. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):695–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Dafny LS, Hendel I, Marone V, Ody C. Narrow networks on the health insurance marketplaces: prevalence, pricing, and the cost of network breadth. Health Aff. 2017;36(9):1606–14. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson EJ, Hassin R, Baker T, Bajger AT, Treuer G. Can consumers make affordable care affordable? The value of choice architecture. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong CA, Polsky DE, Jones AT, Weiner J, Town RJ, Baker T. For third enrollment period, marketplaces expand decision support tools to assist consumers. Health Aff. 2016;35(4):680–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong C, Nirenburg G, Polsky D, Town R, Baker T. Insurance plan presentation and decision support on HealthCare.gov and state-based web sites created for the Affordable Care Act. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(4):327–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Giovannelli J, Curran E. Efforts to support consumer enrollment decisions using total cost estimators: lessons from the Affordable Care Act's marketplaces. Issue Brief. 2017;3:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hempstead K. Consumer decision support on the individual market will be more important than ever. Health Affairs Blog. 2017. Available from: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2017/01/31/consumer-decision-support-on-the-individual-market-will-be-more-important-than-ever/. Accessed 18 March 2018.

- 13.Antos J, Capretta J. The President’s executive order: less than meets the eye? Health Affairs Blog. 2017. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/action/showDoPubSecure?doi=10.1377%2Fhblog20171020.496593&format=full. Accessed 18 March 2018.

- 14.Kaiser Family Foundation. State health insurance marketplace types. 2017. Available from: http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-health-insurance-marketplace-types/. Accessed 18 March 2018.

- 15.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Web-broker public list 2016. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Health-Insurance-Marketplaces/Downloads/Public-2016-WBE-List-20160106.pdf. Accessed 23 Feb 2017.

- 16.Taylor EA, Carman KG, Lopez A, Muchow AN, Roshan P, Eibner C. Consumer Decision Making in the Health Care Marketplace. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson E, Shu SB, Dellaert BG, Fox C, Goldstein DG, Haubl G, et al. Beyond nudges: tools of a choice architecture. Mark Lett. 2012;23:487–504. doi: 10.1007/s11002-012-9186-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith A, Anderson M. Online shopping and E-commerce. 2016. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/12/19/online-shopping-and-e-commerce/. Accessed 18 March 2018.

- 19.Sinaiko AD, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB, Lieu T, Galbraith A. The experience of Massachusetts shows that consumers will need help in navigating insurance exchanges. Health Aff. 2013;32(1):78–86. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao A, White J, Hewitt P. 2017 Health insurance exchanges: the good, the bad and the ugly. Clear Choice. 2017. Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/547e0e88e4b0d4a9ddc29e99/t/588fbb32a5790a510d07a99f/1485814602279/CC+2017+HIX+Report+Final.pdf. Accessed 18 March 2018.

- 21.Zhu JM, Zhang Y, Polsky D. Networks in ACA marketplaces are narrower for mental health care than for primary care. Health Aff. 2017;36(9):1624–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong CA, Kan K, Cidav Z, Nathenson R, Polsky D. Pediatric and adult physician networks in Affordable Care Act marketplace plans. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4). 10.1542/peds.2016-3117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Yala SM, Duru OK, Ettner SL, Turk N, Mangione CM, Brown AF. Patterns of prescription drug expenditures and medication adherence among medicare part D beneficiaries with and without the low-income supplement. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:665. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0665-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson EA, Axelsen KJ. Medicare Part D formulary coverage since program inception: are beneficiaries choosing wisely? Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(11 Suppl):SP29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene J, Hibbard JH, Sacks RM. Summarized costs, placement of quality stars, and other online displays can help consumers select high-value health plans. Health Aff. 2016;35(4):671–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pacific Business Group on Health. Supporting consumers' decisions in the exchange. Available from: http://www.pbgh.org/key-strategies/engaging-consumers/216-supporting-consumers-decisions-in-the-exchange. Accessed 18 March 2018.

- 27.Benedict GC, Baker T. Regulating robo advice across the financial services. Iowa Law Review. 2018;103(forthcoming).