Abstract

Background

Some have questioned whether successful performance in the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program is meaningful. The association of the ABIM Internal Medicine (IM) MOC examination with state medical board disciplinary actions is unknown.

Objective

To assess risk of disciplinary actions among general internists who did and did not pass the MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification.

Design

Historical population cohort study.

Participants

The population of internists certified in internal medicine, but not a subspecialty, from 1990 through 2003 (n = 47,971).

Intervention

ABIM IM MOC examination.

Setting

General internal medicine in the USA.

Main Measures

The primary outcome measure was time to disciplinary action assessed in association with whether the physician passed the ABIM IM MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification, adjusted for training, certification, demographic, and regulatory variables including state medical board Continuing Medical Education (CME) requirements.

Key Results

The risk for discipline among physicians who did not pass the IM MOC examination within the 10 year requirement window was more than double than that of those who did pass the examination (adjusted HR 2.09; 95% CI, 1.83 to 2.39). Disciplinary actions did not vary by state CME requirements (adjusted HR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.16), but declined with increasing MOC examination scores (Kendall’s tau-b coefficient = − 0.98 for trend, p < 0.001). Among disciplined physicians, actions were less severe among those passing the IM MOC examination within the 10-year requirement window than among those who did not pass the examination.

Conclusions

Passing a periodic assessment of medical knowledge is associated with decreased state medical board disciplinary actions, an important quality outcome of relevance to patients and the profession.

KEY WORDS: maintenance of certification, MOC, disciplinary action, ABIM, certification

INTRODUCTION

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) instituted initial certification and maintenance of certification (MOC) examinations in support of its mission “To enhance the quality of health care by certifying internists and subspecialists who demonstrate the knowledge, skills and attitudes essential for excellent patient care.”1 Evidence has accumulated demonstrating that care provided by certified internists, compared to those who are not certified, is associated with better processes and outcomes,2 including mortality.3,4 While associations between certification and better care are fairly widely accepted, fewer studies have assessed associations of care with MOC.5–7 One factor in the controversy over MOC in general, and the MOC examination in particular, has been skepticism about evidence of impact on patient care.8–13

State medical board disciplinary action is an important outcome that matters to patients; it is directly related to quality of patient care and, in many cases, patient safety.14 Higher performance on the ABIM Internal Medicine (IM) initial certification examination is strongly correlated with decreased incidence of state medical board disciplinary actions.15 Physicians certified by ABIM have a five-fold decreased incidence of disciplinary actions compared to those who start IM residency, but fail to become certified.16 Among disciplined physicians, the distribution of severity of actions is less severe in certified compared to never certified physicians.16

Since IM MOC examinations are required at 10-year intervals for physicians initially certified after 1989,2 enough time has passed to accumulate sizable cohorts of physicians required to take the MOC examination to remain certified. Based on findings associated with initial certification, we hypothesized that those who pass the IM MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification would have lower rates of disciplinary actions compared to those who do not take or do not pass the examination. Specifically, we sought to address four primary hypotheses:

There is an inverse association between passing the MOC examination and the risk of disciplinary actions.

The trends in hazard rates for disciplinary actions over time are lower for those passing the MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification compared to those who do not pass within this time frame.

The risk of disciplinary action against physicians declines as scores on the MOC examination increase.

Disciplinary actions are proportionally less severe among those passing the MOC examination compared to those who do not pass within 10 years of initial certification.

METHODS

Study Population

General internists were eligible for inclusion if they passed the ABIM IM certification examination between 1/1/1990 and 12/31/2003 (n = 47,971). We did not include anyone ever certified in an IM subspecialty. Because our focus was the MOC examination and certificates were issued for 10 years during the study period, participants’ start dates in the study began 10 years following their initial certification year. Participants were followed until 12/31/2015. Using data available in the ABIM database, we excluded anyone believed to practice outside the USA (n = 1376), older than 75 years when passing the initial certification examination (n = 2), known to be dead, retired, or in restitution for behaviors not associated with medical licensure (n = 202). Because a disciplined license precludes taking the MOC examination, we excluded those disciplined prior to their study start date (n = 991) to avoid overestimating potential associations with the MOC examination.

Measurements

The primary outcome measure was time (years) to disciplinary action. The Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) provided ABIM information about physicians subjected to medical license-related disciplinary actions through the Disciplinary Action Notification System which provides all sanction records on all physicians in all state medical licensing boards to the certifying boards.17 The primary independent variable was passing the IM MOC examination by the individual’s study start date (initial certification date plus ten full calendar years). Individuals passing the IM MOC examination after their study start date (i.e., the eleventh year after initial certification or later) were defined as having not passed during the study period.

Our full model included variables pertaining to training, certification, physician demographics, and state regulatory environments in which they practiced. All variables were determined a priori and selected to maintain consistency with previous studies on disciplinary action that included similar variables.15,16 Training and certification covariates included years since the first attempt at the IM initial certification examination (a proxy for years from training), year of passing the IM initial certification examination (categorized into five discrete cohorts to account for policy changes over time: 1990–1992, 1993–1995, 1996–1998, 1999–2001, and 2002–2003), and attempts to pass the IM initial certification examination (one vs. more than one).

Demographic variables included sex, age at passing the IM initial certification examination (30 years and younger vs. 31 years and older), birth country (USA vs. international), medical school country (US/Canadian vs. international), and geographic region (Midwest, Northeast, South, and West). Separate variables were created for the four combinations of birth country by medical school country because previous studies suggested different risk profiles for these groups.15

Two indices related to state regulatory environments were created. The first was a state disciplinary rate index for which higher values represented higher disciplinary actions per 1000 physicians in each state and the District of Columbia.18 The second index reflected variability in state CME requirements to maintain licensure such that higher values represented greater CME requirements.19 Both indices were converted to Z-scores with means of zero and unit standard deviations across the 50 states and Washington DC (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Training Characteristics of Internal Medicine Physicians, Initially Certified by ABIM 1990–2003, by Status of Passing the IM MOC Exam (N = 45,400)

| Passed IM MOC exam within 10 years of initial certification (n = 28,178) | Did not pass IM MOC exam within 10 years of initial certification (n = 17,222) | |

|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | ||

| Male, n (%) | 15,978 (56.7) | 10,960 (63.6) |

| > 30 years of age at cohort year*, n (%) | 16,045 (56.9) | 12,683 (73.6) |

| Born outside of USA†, n (%) | 11,853 (42.1) | 8363 (48.6) |

| International medical school graduate‡, n (%) | 9565 (33.9) | 7263 (42.2) |

| Geographic region §, n (%) | ||

| Midwest | 5746 (20.4) | 2882 (16.7) |

| Northeast | 6806 (24.2) | 4474 (26.0) |

| South | 8924 (31.7) | 6141 (35.7) |

| West | 6700 (23.8) | 3646 (21.2) |

| Cohort year ||, n (%) | ||

| 1990–1992 | 3385 (12.0) | 2557 (14.9) |

| 1993–1995 | 5435 (19.3) | 2893 (16.8) |

| 1996–1998 | 8384 (29.8) | 5421 (31.5) |

| 1999–2001 | 6908 (24.5) | 3810 (22.1) |

| 2002–2003 | 4066 (14.4) | 2541 (14.8) |

| > 1 Attempt on IM certification exam, n (%) | 4809 (17.1) | 6259 (36.3) |

| Disciplinary rates index by state¶, mean (SD) | −0.19 (0.87) | −0.19 (0.85) |

| State CME requirement#, mean (SD) | 33.65 (15.99) | 32.87 (15.68) |

| State CME index#, mean (SD) | 0.27 (1.04) | 0.22 (1.03) |

| Disciplined, n (%) | 384 (1.4) | 565 (3.3) |

*Missing: passed MOC, 2; did not pass MOC, 3. Missing values are imputed in regression analysis

†Missing: passed MOC, 74; did not pass MOC, 67. Missing values are imputed in regression analysis

‡Missing: passed MOC, 5; did not pass MOC, 23. Missing values are imputed in regression analysis

§Missing: passed MOC, 2; did not pass MOC, 79. Missing values are imputed in regression analysis. Midwest includes Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota; Northeast includes Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania; South includes Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington DC, and West Virginia; West includes Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming

||Cohort year is the year of the passing attempt on the Internal Medicine initial certification exam

¶A standardized index of physician disciplinary actions taken per 1000 active physicians in each state and the District of Columbia. The state disciplinary rate index is scaled to have a mean of 0 and a SD of 1 across the 50 states and the District of Columbia

#The state CME requirement was based on the number of CME hours that physicians must complete each year to maintain licensure, with an extra 10 points given to states that have additional requirements. In all analyses, a standardized index was used, scaled to have a mean of 0 and a SD of 1 across the 50 states and the District of Columbia

Similar to prior studies,16 disciplinary actions were categorized as very severe if they resulted in loss of licensure, moderately severe if they resulted in license restrictions or probation, and less severe if they resulted only in reprimands or administrative actions (e.g., fines).

Statistical Analysis

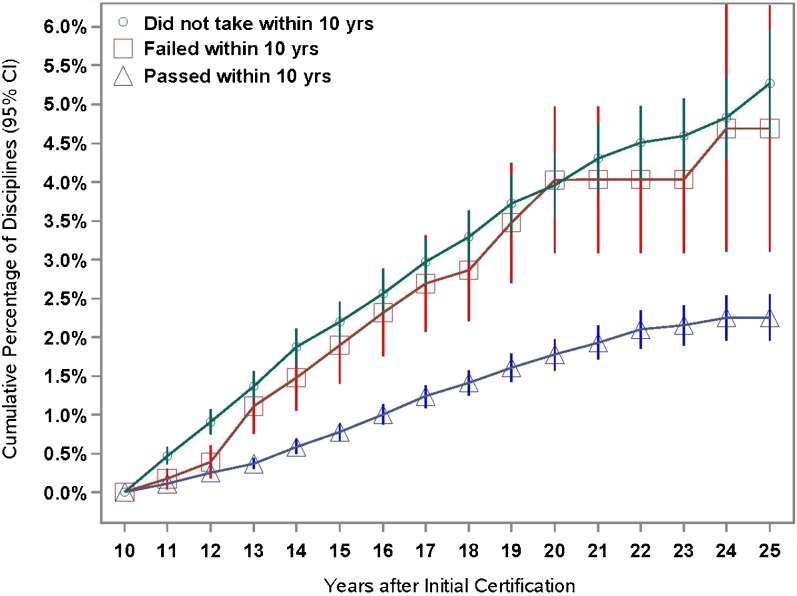

An historical cohort study was designed to compare risks of disciplinary actions over time for physicians passing the IM MOC examination versus those who did not pass within 10 years of initial certification. We used Cox regression to compare disciplinary hazard rates between groups in the previously specified full model (see Table 1). We used accelerated failure time (AFT) regression to produce Kaplan-Meier estimates of cumulative proportions of disciplinary actions over time controlling for all study covariates. Goodness-of-fit indices and visual inspection indicated that we met the assumptions of each model. We graphically compared cumulative proportions of disciplinary actions over time among those who did not take the MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification with those who took and failed the MOC examination in the study period and found them to be similar (Fig. 1), so we retained the primary comparison of those passing the MOC exam in the 10-year requirement window with those who did not pass either because they did not take, or took and failed the examination. Numbers and rates of disciplinary actions among subgroups of those who did not pass the IM MOC examination within 10 years were tabulated. Person-years in the study began from the study start date and continued until a disciplinary action occurred or until the study end date of 12/31/2015. Multiple imputation via the fully conditional specification model was used to replace missing values in covariates, assuming data were missing at random (see Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of cumulative percentage of disciplines by IM MOC examination status within 10 years of initial certification, adjusted for study covariates. The Kaplan-Meier cumulative percentage estimates with pointwise confidence intervals are depicted in the graph. At the end of year 10, the two upper curves represent physicians who did not take an IM MOC examination (green, n = 13,653) or who attempted but did not pass (red, n = 3569), while the lower curve represents physicians who passed an IM MOC examination (blue, n = 28,178) within 10 years of initial certification.

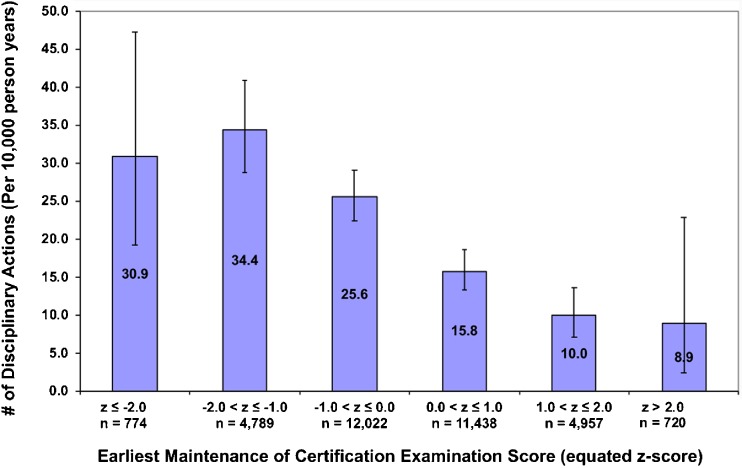

To correlate rates of disciplinary action with performance on first attempt IM MOC examination scores, we used exam Z-scores categorized into six, standard deviation, intervals. Within each interval, we calculated disciplinary actions per 10,000 person-years. We graphed disciplinary rates by Z-score intervals and used Kendall’s tau-b coefficient to gauge the magnitude of association.

We addressed the fourth hypothesis by using the Cochran-Armitage trend test to contrast the proportion of least severe to most severe disciplinary actions by MOC examination status among disciplined physicians.

To assess the possibility that observed associations of disciplinary actions with the IM MOC examination might be related to differences in baseline professionalism, we conducted a post-hoc sensitivity analysis incorporating residency program director ratings of professionalism into the full Cox regression model for all cohorts with complete ratings.

To assess whether initial certification examination score might be a better predictor of discipline than initial certification examination attempts, we conducted a post-hoc sensitivity analysis replacing initial certification examination attempts with the first attempt initial certification examination score in the full model.

P values were two-tailed. Cox regression coefficients were adjusted for multiple comparisons using a Holm stepdown correction. Analysis was conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania approved the study.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of physicians passing and not passing the IM MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification are displayed in Table 1.

Historical Cohort Study

Adjusted hazard ratios for discipline are displayed in Table 2. Among physicians who did not pass the IM MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification, the risk was more than double than that of those who did pass the examination (adjusted HR 2.09 (95% CI 1.83, 2.39)). Physicians who did not pass the IM initial certification examination on the first attempt had a 35% higher risk of discipline (adjusted HR 1.35 (95% CI 1.14, 1.60)) than those passing on the first attempt.

Table 2.

Cox Regression Analysis Predicting Hazard Risk of Discipline, by Person-Years in Study (N = 45,400)

| Predictor variables | Disciplined vs. not disciplined | |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | |

| Training and certification | ||

| Passed MOC exam within 10 years of initial certification (N vs. Y)* | 2.09 †** | (1.83, 2.39) |

| Cohort year‡ (90–92 vs. 02–03) | 1.17 | (0.81, 1.70) |

| Cohort year‡ (93–95 vs. 02–03) | 1.19 | (0.83, 1.70) |

| Cohort year‡ (96–98 vs. 02–03) | 1.36 | (0.96, 1.93) |

| Cohort year‡ (99–01 vs. 02–03) | 1.02 | (0.70, 1.47) |

| Number of attempts on IM cert exam (> 1 vs. 1) | 1.35** | (1.14, 1.60) |

| Years since first IM exam attempt | 0.98 | (0.96, 1.00) |

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Sex (M vs. F) | 1.95** | (1.67, 2.27) |

| Age at cohort year (> 30 vs. ≤ 30 years) | 1.27** | (1.08, 1.50) |

| International birth country/international medical school§ | 1.12 | (0.97, 1.30) |

| International birth country/US/Canadian medical school§ | 0.79 | (0.62, 1.01) |

| US birth country/international medical school§ | 1.33 | (1.01, 1.75) |

| Geographic region (MW vs. NE) | 1.12 | (0.90, 1.40) |

| Geographic region (SO vs. NE) | 1.78** | (1.49, 2.14) |

| Geographic region (WE vs. NE) | 1.32 | (1.07, 1.62) |

| Regulatory Environment | ||

| Disciplinary rates index by state | 1.13** | (1.05, 1.22) |

| State CME requirement index | 1.02 | (0.94, 1.09) |

*“Passed the MOC exam” means physicians passed within the 10-year policy timeframe

†The unadjusted HR for not passing the MOC exam within 10 years is 2.40 (2.11, 2.73)

‡Cohort year is the year of the passing attempt on the IM initial certification exam

§Reference group is US birth country/US/Canadian medical school

**Cells with a double asterisk are statistically significant (P < 0.05) after Holm correction for all the variables used in the full model

Hazard ratios for discipline also differed by demographic characteristics and were higher for physicians who were male versus female (adjusted HR 1.95 (1.67, 2.27)), older than 30 years versus 30 years or younger at training completion (adjusted HR 1.27 (1.08, 1.50)), living in the South (adjusted HR 1.78 (1.49, 2.14)) versus Northeast, and practicing in states with higher disciplinary rates (adjusted HR 1.13 (1.05, 1.22)). Increased state CME requirements were not associated with significant differences in hazard ratios for discipline (adjusted HR 1.02, (0.94, 1.09)).

Numbers and rates of disciplinary actions among subgroups of individuals not passing the IM MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Numbers and Rates of Disciplinary Actions among Subgroups of Physicians Who did and did not Pass the IM MOC Examination within 10 Years of Initial Certification

| Study subgroups | N * | No. (%) of disciplined | Person-years | Discipline rate/10,000 person-years | 95% confidence intervals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passed within 10 years | 28,178 | 384 (1.4) | 217,261 | 17.7 | (16.0, 19.5) |

| Failed within 10 years | 3569 | 94 (2.6) | 24,157 | 38.9 | (31.4, 47.6) |

| Did not take within 10 years | |||||

| Passed after 10 years | 4591 | 138 (3.0) | 39,598 | 34.9 | (29.3, 41.2) |

| Failed after 10 years | 1927 | 105 (5.5) | 14,700 | 71.4 | (58.4, 86.5) |

| Never took MOC exam | 7135 | 228 (3.2) | 55,776 | 40.9 | (35.7, 46.5) |

*Percent of total population (N = 45,400): passed MOC exam within 10 years, 62.1%; failed MOC exam within 10 years, 7.9%; did not take MOC exam within 10 years includes passed on the first attempt after 10 years, 10.1%; failed on the first attempt after 10 years, 4.2%; never took, 15.7%

MOC Examination Score

We found an inverse relationship between IM MOC examination score and rates of disciplinary actions. (Fig. 2, Kendall’s tau-b coefficient = − 0.98 for trend, p < 0.001.)

Fig. 2.

Rates of disciplinary actions per 10,000 person-years (with 95% CIs), by MOC exam Z-score, Fall, 2004–Spring, 2015 (N = 34,700). MOC scores from November, 2004 to May, 2015 were used for the score analysis to keep the format and scale of the examination consistent over time because of a change in MOC exam format beginning in the Fall of 2004. Lower Z-score means lower MOC examination score.

Severity of Discipline

Among disciplined physicians, those passing the IM MOC examination within ten years of initial certification had a higher proportion of less severe disciplinary actions and a lower proportion of very severe actions than those who did not pass (45.0 vs 34.1% and 20.3 vs. 24.7%, respectively, Cochran-Armitage trend test statistic Z = 3.01, P = 0.003).

Sensitivity Analyses

Not passing the IM MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification remained independently associated with higher disciplinary rates in both sensitivity analyses: specifically, controlling for baseline professionalism as measured by adding residency program director professionalism ratings to our full model (adjusted HR 2.1, 95% CI (1.80, 2.44)) and replacing initial certification examination attempts with initial certification examination score in the full model (adjusted HR 2.05, 95% CI (1.78, 2.35)).

DISCUSSION

Among physicians who had been certified for at least 10 years, there was a significant association between not passing the IM MOC examination and state medical board disciplinary actions; specifically, not passing the IM MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification was associated with more than twice the rate of disciplinary actions over time, compared to those who passed the examination. In addition, there was a “dose response” among those who took the IM MOC examination, with higher scores associated with significantly lower disciplinary rates. Finally, disciplinary actions were proportionally less severe among those who passed the IM MOC examination. These findings are similar to associations related to initial certification.15,16 That there is a differential association of disciplinary actions between physicians who did and did not pass the IM MOC examination is important information for patients and health care providers since it provides a marker for physicians who are less likely to have these actions.

About 2% of physicians in this population were disciplined, yet the absolute number receiving disciplinary actions was sizable (n = 949). Given that general internists may have panel sizes of 1000–3000 patients,20,21 the numbers of patients potentially cared for by physicians in this population with disciplinary actions could be conservatively estimated to be many hundreds of thousands to a few million. The large number of patients potentially affected further highlights the relevance of MOC to informing the public’s choice of physicians.22,23

In 2005, Papadakis et al. published the seminal work demonstrating association between professionalism in medical school and subsequent disciplinary actions quantified using Population Attributable Risk (PAR)24 at 26%.25 In comparison, the PAR, or percentage of total disciplinary actions in this population that can be attributed to not having passed the IM MOC exam is 35% (95% CI 28 to 39%).

Some have suggested the association between certification and disciplinary actions may relate more to the professionalism of those certified, compared to those who are not certified, than to medical knowledge.15,25,26 However, our sensitivity analysis suggested passing the IM MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification was associated with reduced disciplinary rates independent of prior professionalism ratings in residency. While it is true that residency ratings of core competencies are inter-correlated,27 our data add to growing evidence suggesting the amount of medical knowledge a physician has acquired, and maintains, is itself associated with better performance and care independent of other acts of professionalism.28–30 This is particularly evident in the “dose response” of examination scores now demonstrated in the United States Medical Licensing Examination,31 certification15 and MOC (Fig. 2); i.e., it is not just passing vs failing that is associated with fewer disciplinary actions; rather, those with demonstrably more medical knowledge (i.e., higher scores) have significantly fewer disciplinary actions than those with lower scores distributed in a score-dependent gradient. Similarly, those who require more than one attempt to pass the IM initial certification examination are at greater risk for disciplinary actions (Table 2). Finally, those who fail the IM MOC examination have similarly higher disciplinary rates than those who do not take the IM MOC examination within 10 years of initial certification (Fig. 1). If it were merely an “act of professionalism” to complete the MOC process, then those who take but fail the examination should have disciplinary rates closer to those who take and pass the examination. However, these data demonstrate the opposite; supporting the hypothesis that more medical knowledge is associated with fewer disciplinary actions.

A close examination of published causes of disciplinary actions may reveal a rationale for the association between increased medical knowledge and fewer disciplinary actions. While it is true that Morrison et al. found in their large state sample of causes for discipline that most disciplinary actions might be categorized as lapses in professionalism, the single largest category was “negligence or incompetence” accounting for 34% of the causes of discipline.14 It is possible that physicians staying more current in knowledge and practice may well be more likely to recognize and provide appropriate care, thus avoiding actions considered as “negligence or incompetence.”

Some critics of MOC have suggested that CME is sufficient demonstration of staying current in knowledge and practice.13,32–34 However, our study included differential CME amounts required by state medical licensing boards and found no difference in disciplinary rates associated with the amount of CME required for licensure, suggesting that completing CME alone does not reduce the risk of disciplinary action. By contrast, passing the IM MOC examination was the single strongest factor associated with fewer disciplinary actions in our analysis of this population.

Our study has limitations. First, this is a population-based cohort study, a strong study design for prognosis of outcomes like disciplinary actions, yet it is an observational study, and thus cannot determine causality. Second, while we did adjust for known and potentially associated variables, it is possible that factors for which we did not account may affect the risk of disciplinary actions. For example, our study may underestimate the association of not passing the IM MOC examination and disciplinary actions because some licensed physicians may have left the practice of medicine and, therefore, were no longer at risk for disciplinary actions. Published rates of attrition of general internists from the practice of medicine in the last decade were between 1735 and 23%36; whereas, there were only 16% in our population who never took the IM MOC examination, and this group had significantly higher rates of disciplinary actions than those who took and passed the MOC examination within 10 years (Table 3), indicating many were still practicing medicine. Insofar, as attrition from the practice of medicine may have occurred for some who never took the IM MOC examination, these already higher rates of disciplinary action would be underestimates of the true association. Also, we did not have a measure of patient volume per physician for our cohort. While some studies have demonstrated an association between patient volume and patient outcomes,3,4 others have not.37–40 Even in those that did demonstrate an association, the magnitude of association was small; so, patient volume metrics, if added to our model, would be unlikely to change significantly the association of passing the IM MOC examination with disciplinary actions. Third, our study population included only general internists, the largest group of physicians certified. Future studies could assess similar associations in subspecialists. Fourth, our study excluded physicians disciplined within the first 10 years after initial certification, so our results are most generalizable to physicians who similarly were not disciplined in the first 10 years after initial certification, but this includes more than 98% of all physicians initially eligible for inclusion in our study. Fifth, we did not assess associations of disciplinary actions for physicians who were certified prior to 1990 because these physicians are not required to take the MOC examination to maintain their “time-unlimited” or “grandfathered” certificates.41 This may warrant future study given our finding that increased age is associated with increased risk of disciplinary actions.

In conclusion, this study provides important evidence to support the concept that passing a periodic assessment of medical knowledge among practicing physicians is associated with enhancing the quality of healthcare.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following individuals for their critical review of the manuscript: Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP; Richard J. Baron, MD; J. Taylor Hays, MD, Joseph C. Kolars, MD.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania approved the study.

Conflict of Interest

All authors are employed by the American Board of Internal Medicine.

References

- 1.Baron RJ, Johnson D. The American Board of Internal Medicine: Evolving Professional Self-regulation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;161(3):221–3. doi: 10.7326/M13-2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipner RS, Hess BJ, Phillips RL. Specialty Board Certification in the United States: Issues and Evidence. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2013(S1):20–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Norcini JJ, Kimball HR, Lipner RS. Certification and specialization: do they matter in the outcome of acute myocardial infarction? Academic Medicine: Journal Of The Association Of American Medical Colleges. 2000;75(12):1193–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Fiorilli PN, Minges K, Herrin J, et al. Association of physician certification in Interventional Cardiology with in-hospital outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2015;132(19):1816–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray BM, Vandergrift JL, Johnston MM, et al. Association Between Imposition of a Maintenance of Certification Requirement and Ambulatory Care-Sensitive Hospitalizations and Health Care Costs. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312(22):2348–57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Holmboe ES, Wang Y, Meehan TP, et al. Association Between Maintenance of Certification Examination Scores and Quality of Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(13):1396–403. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes J, Jackson JL, McNutt GM, Hertz BJ, Ryan JJ, Pawlikowski SA. Association between physician time-unlimited vs time-limited internal medicine board certification and ambulatory patient care quality. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2358–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook DA, Holmboe ES, Sorensen KJ, Berger RA, Wilkinson JM. Getting maintenance of certification to work: A grounded theory study of physicians’ perceptions. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015;175(1):35–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Iglehart JK, Baron RB. Ensuring physicians’ competence—Is maintenance of certification the answer? The New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(26):2543–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1211043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drazen JM, Weinstein DF. Considering Recertification. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(10):946–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1000174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levinson W, King TE. American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification Program. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(10):948–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMclde0911205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook DA, Blachman MJ, West CP, Wittich CM. Physician attitudes about Maintenance of Certification: A cross-specialty national survey. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2016;91(10):1336–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teirstein PS, Topol EJ. The role of maintenance of certification programs in governance and professionalism. JAMA. 2015;313(18):1809–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison J, Wickersham P. Physicians disciplined by a state medical board. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(23):1889–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Papadakis MA, Arnold GK, Blank LL, Holmboe ES, Lipner RS. Performance during Internal Medicine Residency Training and Subsequent Disciplinary Action by State Licensing Boards. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148(11):869–76. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-11-200806030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipner RS, Young A, Chaudhry HJ, Duhigg LM, Papadakis MA. Specialty Certification Status, Performance Ratings, and Disciplinary Actions of Internal Medicine Residents. Academic Medicine. 2016;91(3):376–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Johnson DA, Chaudhry HJ. Medical Licensing and Discipline in America: A History of the Federation of State Medical Boards. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfe S, Williams C, Zaslow A. Public Citizen’s Health Research Group Ranking of the Rate of State Medical Boards’ Serious Disciplinary Actions, 2009–2011. 2012.

- 19.Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States: Continuing Medical Education Board by Board Overview: 2015.

- 20.Hong CS, Atlas SJ, Chang Y, et al. Relationship between patient panel characteristics and primary care physician clinical performance rankings. JAMA. 2010;304(10):1107–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raffoul M, Moore M, Kamerow D, Bazemore A. A Primary Care Panel Size of 2500 Is neither Accurate nor Reasonable. Journal Of The American Board Of Family Medicine: JABFM. 2016;29(4):496–9. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.04.150317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cassel CK. ABIM: Maintenance of Certification—For the public. 2010.

- 23.Brennan TA, Horwitz RI, Duffy FD, Cassel CK, Goode LD, Lipner RS. The Role of Physician Specialty Board Certification Status in the Quality Movement. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(9):1038–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.9.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleiss J, Levin B, Paik M. Statistical Methods for Rate and Proportions. 3rd ed Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2003:125–9.

- 25.Papadakis MA, Teherani A, Banach MA, et al. Disciplinary Action by Medical Boards and Prior Behavior in Medical School. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(25):2673–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa052596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papadakis MA, Hodgson CS, Teherani A, Kohatsu ND. Unprofessional behavior in medical school is associated with subsequent disciplinary action by a state medical board. Academic Medicine: Journal Of The Association Of American Medical Colleges. 2004;79(3):244–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauer KE, Clauser J, Lipner RS, et al. The Internal Medicine Reporting Milestones: Cross-sectional Description of Initial Implementation in U.S. Residency Programs. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2016;165(5):356–62. doi: 10.7326/M15-2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald F, Zeger S, Kolars J. Factors associated with medical knowledge acquisition during internal medicine residency. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(7):962–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0206-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald F, Zeger S, Kolars J. Associations of conference attendance with internal medicine in-training examination scores. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2008;83(4):449–53. doi: 10.4065/83.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCoy CP, Stenerson MB, Halvorsen AJ, Homme JH, McDonald FS. Association of volume of patient encounters with residents’ in-training examination performance. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28(8):1035–41. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2398-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuddy M, Young A, Gelman A, et al. Exploring the relationships between USMLE performance and disciplinary action in practice: A validity study of score inferences from a licensure examination. Academic Medicine. 2017;92(12):178–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Aboud KA, Ramesh V. Continuing Medical Education (CME): A reappraisal. Canadian Medical Education Journal. 2011;2(2):e91–e3. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed K, Wang TT, Ashrafian H, Layer GT, Darzi A, Athanasiou T. The effectiveness of continuing medical education for specialist recertification. Canadian Urological Association Journal—Journal De L’association Des Urologues Du Canada. 2013;7(7–8):266–72. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balmer JT. The transformation of continuing medical education (CME) in the United States. Advances in Medical Education & Practice. 2013;4:171–82. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S35087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bylsma W, Arnold GK, Fortna GS, Lipner R. Where have all the general internists gone? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(10):1020. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1349-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipner RS, Bylsma WH, Arnold GK, Fortna GS, Tooker J, Cassel CK. Who Is Maintaining Certification in Internal Medicine--and Why? A National Survey 10 Years after Initial Certification. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;144(1):29–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casalino LP, Pesko MF, Ryan AM, et al. Small Primary Care Physician Practices Have Low Rates Of Preventable Hospital Admissions. Health Affairs. 2014;33(9):1680–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kralewski J, Dowd B, Knutson D, Tong J, Savage M. The relationships of physician practice characteristics to quality of care and costs. Health Services Research. 2015;50(3):710–29. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pineault R, Provost S, Borgès Da Silva R, Breton M, Levesque J-F. Why Is Bigger Not Always Better in Primary Health Care Practices? The Role of Mediating Organizational Factors. Inquiry: A Journal Of Medical Care Organization, Provision And Financing. 2016;53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Shortell SM, Schmittdiel J, Wang MC, et al. An Empirical Assessment of High-Performing Medical Groups: Results from a National Study. Medical Care Research & Review. 2005;62(4):407–34. doi: 10.1177/1077558705277389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipner RS, Bylsma WH, Arnold GK, Fortna GS, Tooker J, Cassel CK. Who is maintaining certification in internal medicine -- and why? A national survey 10 years after initial certification. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;144(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed]