Abstract

cAMP, the classical second messenger, regulates many diverse cellular functions. The primary effector of cAMP signals, protein kinase A, differentially phosphorylates hundreds of cellular targets. Little is known, however, about the spatial and temporal nature of cAMP signals and their information content. Thus, it is largely unclear how cAMP, in response to different stimuli, orchestrates such a wide variety of cellular responses. Previously, we presented evidence that cAMP is produced in subcellular compartments near the plasma membrane, and that diffusion of cAMP from these compartments to the bulk cytosol is hindered. Here we report that a uniform extracellular stimulus initiates distinct cAMP signals within different cellular compartments. By using cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels engineered as cAMP biosensors, we found that prostaglandin E1 stimulation of human embryonic kidney cells caused a transient increase in cAMP concentration near the membrane. Interestingly, in the same time frame, the total cellular cAMP rose to a steady level. The decline in cAMP levels near the membrane was prevented by pretreatment with phosphodiesterase inhibitors. These data demonstrate that spatially and temporally distinct cAMP signals can coexist within simple cells.

Much has been learned about the enzymes involved in the generation and breakdown of cAMP (1, 2) and the proteins that mediate the downstream effects of cAMP (3–6). However, conventional methods have, by and large, been unable to resolve the spatial and temporal features of cAMP signals. Creative attempts to use protein kinase A (PKA) or L-type Ca2+ channels to assess changes in cAMP levels have yielded some information. In large invertebrate neurons, gradients in cAMP between the processes and the soma have been inferred (7, 8). Gradients in cAMP have also been deduced in studies of cardiac myocytes, in which only part of the cell was stimulated with isoproterenol (9). Unfortunately, these methods have limited resolution. It has been shown previously that heterologously expressed cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels are able to detect changes in membrane-localized cAMP concentration (10–12) and, by using the patch–cram technique, cytosolic cGMP (13) in real time. The properties of CNG channels can be tailored for the measurement of submicromolar cAMP concentrations (11). These methodological advances allow the measurement of cAMP produced by low levels of adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity without the need to inhibit phosphodiesterase (PDE) (11, 12).

In this study, we compared measurements of membrane-localized and total cellular cAMP levels in response to prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) stimulation. We used the olfactory CNG channel α subunit containing two mutations, C460W and E583M, to monitor cAMP levels near the surface membrane in both cell populations and single cells. These mutations make it possible to measure cAMP concentrations in the 100 nM range, while rendering the channel relatively insensitive to cGMP. We assessed total cAMP accumulation in cell populations by measuring the conversion of [3H]ATP into [3H]cAMP. The difference between the two measured cAMP signals was striking: a rise and fall in cAMP near the membrane and an increase to a steady level throughout the cell. The segregation of signals helps to explain how cAMP can differentially regulate cellular targets.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Channel Expression.

Human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells were maintained in culture and infected with adenovirus as described previously (11). An adenovirus encoding the α subunit of the rat olfactory CNG channel (CNG2, CNCα3) with mutations C460W and E583M was constructed by using the Quik Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) and a modification of the AdEasy system (14, 15). All cells used in cAMP assays were treated with this adenovirus.

Measurement of Total cAMP Accumulation in Cell Populations.

Static cAMP accumulation in intact cells was measured as described previously (16) with some modifications. HEK-293 cells plated on 100-mm dishes were incubated in MEM containing FBS (10%) with [2-3H]adenine (20 μCi/dish; 90 min at 37°C) to label the ATP pool. Cells were washed once and resuspended in a buffer containing (mM): 145 NaCl, 11 d-glucose, 10 Hepes, 4 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 1 mg/ml BSA, pH 7.4. After the start of an experiment, aliquots (900 μl) were removed every 10 s and immediately added to trichloroacetic acid [100 μl; 100% (wt/vol)] to terminate the reaction. After pelleting, the [3H]ATP and [3H]cAMP content of the supernatant were quantified as described previously (17). Results are expressed as the percent conversion of [3H]ATP into [3H]cAMP and represent the total accumulation over time.

Detection of Local cAMP in Cell Populations.

Increases in local cAMP concentration activate CNG channels and trigger Ca2+ entry. Ca2+ influx was monitored in cell populations by using the fluorescent indicator fura-2. Cells were loaded with 4 μM fura-2/AM and 0.02% pluronic F-127 for 30–40 min in a buffer containing Ham's F-10 medium supplemented with 1 mg/ml of BSA and 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4. Cells were washed twice, resuspended in the buffer described above (3–4 × 106 cells/3 ml of buffer solution), and assayed by using an LS-50B spectrofluorimeter (Perkin–Elmer). Additions were made by pipetting stock solutions into a stirred cuvette (mixing time ≈5 s). Fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 510 nm. Under these conditions, Ca2+ influx causes a decrease in fluorescence (ΔF), which was expressed relative to the prestimulus fluorescence (F0) to correct for variations in dye concentration and to allow for comparison of results on different batches of cells. ΔF/F0 was plotted with inverted polarity, so that increases in Ca2+ influx were represented as positive deflections. Linear fits to the steady-state Ca2+ influx rates were used to quantify the results (11). The matlab software package (Mathworks, Natick, MA) was used for curve fitting and simulations.

Measurement of Local cAMP in Single Cells.

Single-cell cAMP measurements were made by using either the perforated patch or whole-cell patch–clamp technique (10). In the perforated patch configuration, the pore-forming antibiotic nystatin was added to the pipette solution to gain electrical access to the cell's interior while retaining divalent cations and larger molecules like cAMP in the cell. Recordings were made by using an Axopatch-200A patch–clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Pipette resistance was limited to 5 MΩ and averaged 3.4 ± 0.5 MΩ (measurements throughout the paper are expressed as mean ± standard deviation). In the perforated patch configuration, a steady access resistance was obtained 5–15 min after seal formation. Capacitive transients were elicited by applying −30 mV steps from the holding potential of −20 mV for calculation of access resistance (100 ± 40Ω). These quantities were monitored throughout the experiments to ensure stable electrical access was maintained. Current records were typically sampled at five times the filter setting. Records were digitally filtered at 12 Hz, resampled at 60 Hz, and corrected for series resistance errors. The control bath solution contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 11 d-glucose, 10 Hepes, and either 0.1 or 10 MgCl2, pH 7.4. Forskolin, PGE1, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), and 4-(3-butoxy-4-methoxybenzyl)-2-imidazolidinone (RO-20–1724) were added to the control solution from concentrated DMSO stocks, with final concentrations as indicated (final DMSO concentrations were <0.5%). Solutions were applied by using the SF-77B fast-step solution switcher (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). The mechanical switch time was 1 ms. The time to exchange the extracellular solution was measured by applying a 140 mM KCl solution to a depolarized cell (+50 mV) and monitoring changes in current through endogenous voltage-gated K+ channels; for each experiment, the exchange time was less than 60 ms. The pipette solution in perforated patch experiments contained (mM): 70 KCl, 70 potassium gluconate, 4 NaCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, pH 7.4, and 50–200 μg/ml of nystatin. In most of these experiments, the pipette solution also contained 1 mM cAMP; at the end of the experiment, the maximal cAMP-induced current could be measured by rupturing the cell membrane at the tip of the pipette with suction, allowing saturating cAMP to diffuse to the channels (10). In whole-cell experiments, 5 mM K2ATP were added to the pipette solution, and nystatin was not included.

Calibration of Single-Cell Measurements.

The cyclic nucleotide sensitivity of the C460W/E583M CNG channel was assessed in excised inside-out patches as described previously (11). The data were fitted with the Hill equation, I/Imax = [cAMP]N/([cAMP]N + K ), where I/Imax is the fraction of maximal current, K1/2 is the cAMP concentration that gives a half-maximal current, and N is the Hill coefficient. K1/2 and N were 1.1 ± 0.3 μM and 2.1 ± 0.4 at + 50 mV, and 1.0 ± 0.3 μM and 2.0 ± 0.3 at −50 mV (n = 11). With these values, the cAMP concentration could be calculated from currents measured in perforated patch experiments (10). For example, if I/Imax were found to be 0.6, the estimated cAMP concentration would be 1.2 μM. It should be noted that the low concentration of channels expressed in these cells (≈1 nM) did not significantly buffer the measured cAMP signals.

), where I/Imax is the fraction of maximal current, K1/2 is the cAMP concentration that gives a half-maximal current, and N is the Hill coefficient. K1/2 and N were 1.1 ± 0.3 μM and 2.1 ± 0.4 at + 50 mV, and 1.0 ± 0.3 μM and 2.0 ± 0.3 at −50 mV (n = 11). With these values, the cAMP concentration could be calculated from currents measured in perforated patch experiments (10). For example, if I/Imax were found to be 0.6, the estimated cAMP concentration would be 1.2 μM. It should be noted that the low concentration of channels expressed in these cells (≈1 nM) did not significantly buffer the measured cAMP signals.

Data in figures are representative of at least four experiments. All experiments were done at room temperature (19–22°C). Forskolin and PDE inhibitors were from Calbiochem. Fura-2/AM and pluronic F-127 were from Molecular Probes. [2-3H]adenine, [3H]cAMP, and [α-32P]ATP were from Amersham Pharmacia. All other chemicals were from Sigma.

Results and Discussion

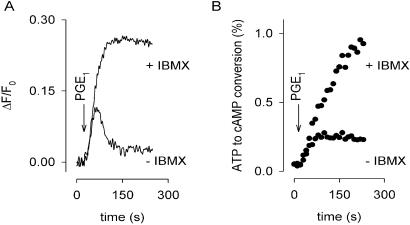

We examined cAMP levels in HEK-293 cells in response to PGE1 stimulation. HEK-293 cells express a variety of extracellular receptors including prostanoid receptors (18), and the cAMP-specific PDE type IV (11, 19). They also appear to express AC types II, III, VI, and VII, on the basis of PCR analysis (20). C460W/E583M channels were expressed heterologously by using an adenovirus construct (11). We have taken advantage of the Ca2+ permeability of the channel to detect changes in local cAMP concentration; the fluorescent indicator fura-2 was used to monitor Ca2+ entry. With this approach, incremental changes in cAMP concentration are readily detected as changes in relative Ca2+ influx rates through C460W/E583M channels (11). Fig. 1 shows a comparison of membrane-localized (A) and total cAMP (B) levels in cell populations. In Fig. 1A, sustained application of 10 μM PGE1 in the absence of PDE inhibitor caused an increase in Ca2+ influx, followed by a decline in Ca2+. Little or no increase in Ca2+ was observed in cells not expressing the channel. Our initial interpretation was that PGE1 triggered a rise and fall in local cAMP concentration: the rise caused an increase in Ca2+ influx through CNG channels; the subsequent fall in cAMP led to reduced Ca2+ influx, and Ca2+ pumping mechanisms caused the decline in Ca2+ levels. In support of this interpretation, PGE1 in the presence of the PDE inhibitor IBMX caused Ca2+ to rise along a similar time-course, but the decay phase was abolished. These results indicate that the underlying cause of the decay phase was hydrolysis of cAMP. In populations of cells expressing C460W/E583M channels, PGE1 caused total cellular cAMP accumulation, assessed as the conversion of [3H]ATP to [3H]cAMP, to rise to a plateau in the absence of IBMX (Fig. 1B), in marked contrast to the transient increase in cAMP inferred from Fig. 1A.

Figure 1.

Distinct cAMP signals measured in different subcellular compartments. (A) Membrane-localized cAMP signals were detected in cell populations by using Ca2+ influx through C460W/E583M channels. Ca2+ influx caused a decrease in fluorescence (ΔF/F0, plotted with inverted polarity). In the absence of PDE inhibitors (−IBMX), 10 μM PGE1 (arrow) triggered a rise and fall in Ca2+. The decay of the Ca2+ response was prevented by 5-min pretreatment with 100 μM IBMX. (B) Total cellular cAMP accumulation was determined in cell populations by monitoring the conversion of [3H]ATP to [3H]cAMP. PGE1 (10 μM) caused cellular cAMP to rise to a plateau in the absence of PDE inhibitors. A steady increase in cAMP was observed when cells were pretreated with 100 μM IBMX for 5 min.

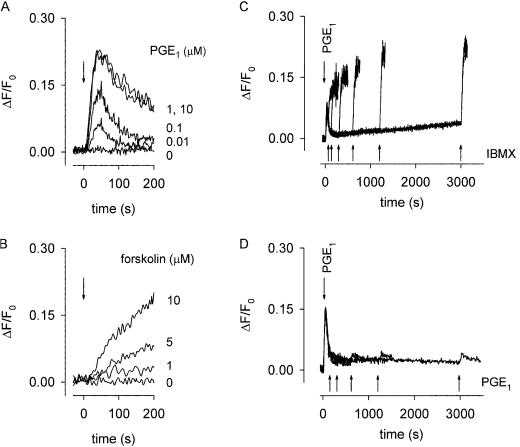

The basis for the transient response was investigated further in Fig. 2. Transient responses were observed over a large range of PGE1 concentrations, from 0.01 to 10 μM (Fig. 2A). Forskolin, an activator of AC, also triggered dose-dependent rises in Ca2+ influx (Fig. 2B). However, these responses, unlike the PGE1-induced responses, did not decline. Similarly, by using the same assay, the responses of rat glioma C6–2B cells to isoproterenol, and rat pituitary-derived GH4C1 cells to vasoactive intestinal peptide did not decline on a similar time-scale (11, 12). Thus, the activation of AC alone does not necessarily cause transient Ca2+ responses. Taken together, these results suggest that the decline was because of a reduction in AC activity and/or an increase in PDE activity. The decline was unlikely to result primarily from a reduction in AC activity (e.g., receptor desensitization) because of the sustained accumulation of total cellular cAMP in the presence of IBMX (Fig. 1B). To verify this interpretation, we added 100 μM IBMX at various times after PGE1 application. Even 50 min after the addition of PGE1, IBMX triggered a rapid Ca2+ influx (Fig. 2C), indicative of a sharp rise in cAMP level. The type-IV-specific PDE inhibitor RO-20–1724 (10 μM) also caused sharp increases in cAMP (the maximal slopes were indistinguishable from those induced by IBMX). In the absence of PGE1, PDE inhibitors caused no measurable Ca2+ influx. These experiments suggest that AC activity did not decrease appreciably, but instead that PDE activity was up-regulated. To test whether PGE1 did indeed increase the total PDE activity, we added 100 nM PGE1 at various times after the initial application of 100 nM PGE1 (a subsaturating concentration). There was a negligible response to the subsequent addition of PGE1, even after 50 min (Fig. 2D). Taken together, the experiments in Fig. 2 C and D argue that the cAMP transient is caused by an initial increase in AC activity, followed by a more profound increase in PDE activity. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that neurotransmitters and hormones, including PGE1, regulate PDE activity as well as cyclase activity (13, 21–24). Here we show that such mechanisms are crucial for the generation of spatially and temporally distinct cAMP signals.

Figure 2.

PGE1 triggers sustained AC and PDE activity. (A and B) Local cAMP changes in response to AC stimulation, monitored by Ca2+ influx through C460W/E583M channels. PGE1 (A) or forskolin (B) were applied at the indicated concentrations. (C) Rises in cAMP (monitored by Ca2+ influx) caused by 100 nM PGE1 (t = 0) and subsequent addition of 100 μM IBMX (1, 2, 5, 10, 20, or 50 min, superimposed traces). The slopes of the IBMX-induced responses (0.0044 ± 0.0008 s−1) were similar to each other and to the slopes of the initial PGE1-induced responses (0.0038 ± 0.0003 s−1). IBMX and RO-20–1724 had no effect on channel activity in excised membrane patches (11). (D) Second additions of 100 nM PGE1 (2, 5, 10, 20, or 50 min, superimposed traces) after the initial addition of 100 nM PGE1 (t = 0) gave little or no response.

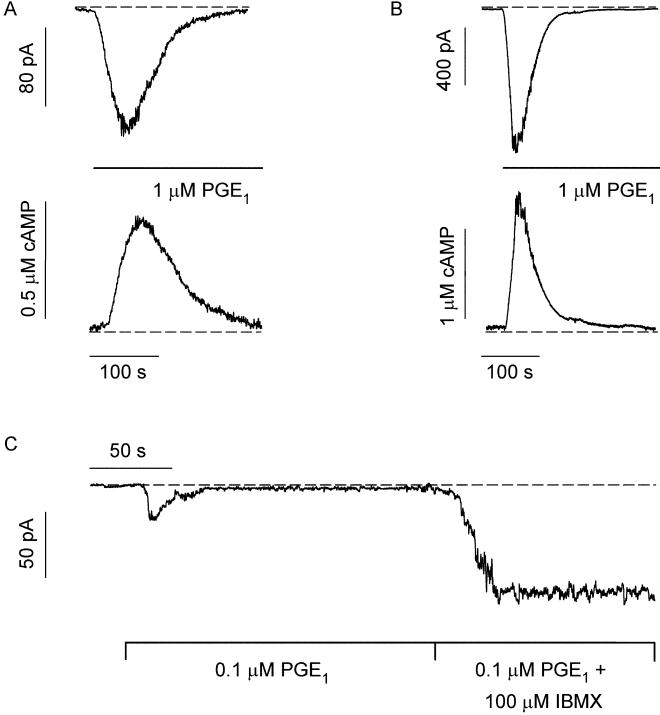

We next sought to examine the response to PGE1 in single cells, by directly measuring ionic currents through C460W/E583M channels with the perforated patch-clamp technique. This approach has higher temporal resolution and dynamic range than the Ca2+ influx assay, and the response can be calibrated, allowing for accurate measurement of cAMP concentration. These experiments were done in nominally Ca2+-free solutions, which increased currents through the channels (Ca2+ is a permeant blocker) and removed the possibility that Ca2+ entry inhibited the channels (6). The responses of two different cells to rapid application of 1 μM PGE1 are shown in Fig. 3 A and B. Inward currents were measured at a holding potential of −20 mV. The currents were converted to cAMP concentration on the basis of the channel's dose-response relation determined in excised membrane patches (see Materials and Methods). The cAMP signals were transient, rising more sharply than they decayed, in general agreement with the cAMP changes inferred from Ca2+ influx experiments in cell populations. (The absence of extracellular Ca2+ in these experiments, and, as noted earlier, the lack of a PGE1-stimulated rise in intracellular Ca2+ in control cells, indicate that the transient cAMP responses were not caused by Ca2+ feedback mechanisms. For additional controls, see the Fig. 3 legend.) The shapes of the responses were similar across six cells, but the kinetics varied (width at half-height 87 ± 53 s). The time-course in Fig. 3A was about average for the single-cell measurements, whereas the time-course in Fig. 3B (from a different cell) was considerably faster. The average amplitude of the cAMP signal in five cells was 0.7 ± 0.4 μM. When 100 μM IBMX was added after 100 nM PGE1 (Fig. 3C), the current rose to a plateau (n = 4). This result demonstrates the persistent activation of AC by PGE1, as observed in cell populations (Fig. 2C).

Figure 3.

Single-cell measurements of local cAMP signals. (A and B) Upper: Rapid application of PGE1 triggered transient inward currents through CNG channels (−20 mV). Two different cells monitored in perforated patch configuration. Lower: the corresponding cAMP signals calibrated as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Rapid application of PGE1 triggered a transient inward current (whole-cell configuration, −20 mV). Subsequent application of PGE1 and IBMX triggered an inward current that rose to a plateau. This current was blocked by 10 mM MgCl2 (characteristic of CNG channels). Dashed lines indicate either zero cyclic nucleotide-induced current (the current in 10 mM MgCl2) or zero cAMP. No PGE1-induced currents were observed in cells not expressing CNG channels. Several additional controls were done to ensure that the PGE1-induced signal was a rise and fall in cAMP. PGE1 had no direct effect on channels in excised membrane patches, and when it was applied to cells it did not affect the cAMP sensitivity, the conductance, nor the number of active channels. In addition, treatment of CNG-channel-expressing cells with PGE1 triggered little or no release of Ca2+ from internal stores and no measurable increases in cGMP (Figs. 5 and 6, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org).

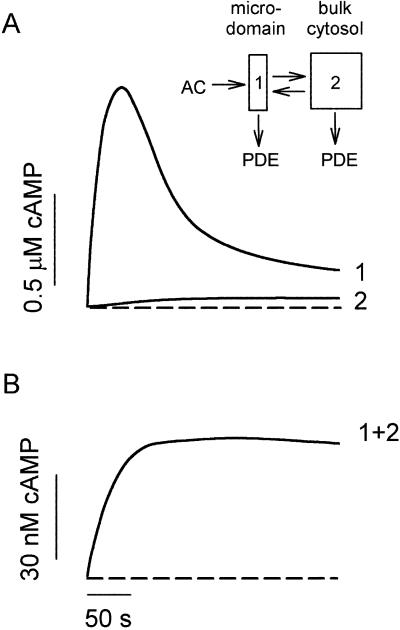

How can cAMP signals near the channels be distinct from those in other parts of the cell? Several lines of evidence presented previously suggest that cAMP is produced in subcellular compartments near the surface membrane, and that diffusion between these domains and a cytosolic compartment is significantly impeded (10). At a minimum, it is necessary to invoke the same two compartments to explain the current data. With no restriction on diffusion: (i) cAMP concentrations right next to AC are not high enough to activate PKA (10), let alone the CNG channels used here (unless the entire cell filled with cAMP); and (ii) cAMP would diffuse across a 15–20 μm cell in <0.2 s, which would “wash out” any spatial differences on a time-scale of tens to hundreds of seconds. Fig. 4A Inset shows the two compartment model presented before, with two important additions: a PGE1-induced increase in PDE activity in compartment 1, and a constitutively active PDE in compartment 2. The system is described by the following equations:

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

where V1 and V2 are the volumes of compartments 1 and 2, C1 and C2 are the cAMP concentrations, J12 is the flux coefficient between compartments, EAC is the synthesis rate of cAMP, E1 and E2 are the maximal cAMP hydrolysis rates, KM1 and KM2 are the Michaelis constants for PDE activity, A and I are the fraction of active and inactive PDE in compartment 1 (A + I = 1), and kA and kI are the rate constants of PDE activation and inactivation. The parameters J12 = 8.0 × 10−16 liters/s, V1 = 0.040 pL, and V2 = 2.0 pL are the same as those used previously (10). AC activity is considered constant, with EAC = 0.13 μM/s. KM1, E1, KM2, and E2 are 0.30 μM, 0.83 μM/s, 1.0 μM, and 0.0020 μM/s. The rate constants kA and kI are 0.0015 s−1 and 0.0010 s−1. The initial and final (300 s) values of A are 0.10 and 0.36. The parameters used here reflect similar total PDE activities near the plasma membrane and throughout the cytosol, in broad agreement with experiments on PDE type IV in several cell types (24).

Figure 4.

A quantitative description of the localized transient cAMP response and the total cellular cAMP accumulation. (Inset) Two-compartment model of the cell with a diffusional restriction between the membrane-localized microdomain (compartment 1) and the bulk cytosol (compartment 2). See text for details. (A) Rapid activation of AC and slower activation of PDE shape the transient signal in the microdomain. The slow flux of cAMP from the microdomain allows low levels to accumulate in the cytosol. Note that even in the small volume of the microdomain, the concentration of CNG channels would be low (≈40 nM) and would not be expected to buffer the measured cAMP signal. (B) Total cAMP levels (microdomain and cytosol) reach a plateau. Dashed lines indicate zero cAMP.

Simulations of the model successfully reproduce the local transient change in cAMP, as well as the rise in total cAMP to a plateau (Fig. 4). A PGE1-induced increase in PDE activity within compartment 1 is required to explain the data. Slow efflux of cAMP from the microdomain is ultimately balanced by low rates of hydrolysis within the bulk cytosol. Thus, different relative PDE activities within more than one diffusionally restricted compartment can explain the generation of distinct cAMP signals, even in a simple, nonexcitable cell.

In morphologically complex cells like neurons, dendritic spines and other subcellular structures have been shown to be diffusionally isolated compartments (25–29). Surprisingly, the current findings demonstrate that the concept of three-dimensional barriers to diffusion may be generalized to simple cells, which are usually considered to contain a single homogeneous cytosolic compartment. The exact nature of the diffusional barrier is unclear, but it is likely to be formed, at least in part, by endoplasmic reticulum membrane that is known to come in close apposition to the plasma membrane (30–32). Although localized Ca2+ signals have been measured (33, 34), these have been attributed primarily to proximity to high-throughput Ca2+ sources and the delimiting effects of high-capacity cellular buffers, rather than diffusional barriers. However, the diffusional barriers to cAMP discussed here could also influence local Ca2+ signals.

In conclusion, we have resolved distinct cAMP signals in different compartments of a simple nonexcitable cell: a transient signal in microdomains near the surface membrane and a signal that rises to a plateau throughout the cell. Diffusional restrictions between the microdomains and the cytosol, as well as differential regulation of PDE activity, are required to generate such distinct signals. Segregated cAMP signals allow for differential regulation of cAMP effector proteins like PKA. A similar scenario may explain a long-standing observation in cardiac myocytes: two agents that both trigger rises in cAMP (PGE1 and isoproterenol) have markedly different downstream effects (35). Comparable observations have been made in studying the effects of β1- and β2-adrenergic agonists (35–37). In this context, it is interesting to reconsider the possible functions of A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs), the scaffolds that tether PKA to cellular targets (4, 38). In addition to creating two-dimensional protein arrays that help to ensure the phosphorylation of certain proteins, AKAPs are likely to direct PKA to diffusionally isolated cellular regions in which distinct cAMP signals are produced. The transient nature of the signals measured here will limit the diffusional spread of cAMP. However, these signals should still allow for a prolonged activation of PKA because the reassociation of PKA subunits is slow (39, 40). A challenge for the future will be to decipher the specific information encoded in the different cAMP signals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY09275, NS28389, HL58344, and American Heart Association Grant DM0020554Z.

Abbreviations

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PGE1

prostaglandin E1

- CNG channel

cyclic nucleotide-gated channel

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Sunahara R K, Dessauer C W, Gilman A G. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:461–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beavo J A. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:725–748. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.4.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh D A, Perkins J P, Krebs E G. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:3763–3765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray P C, Scott J D, Catterall W A. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:330–334. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francis S, Corbin J D. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1999;36:275–328. doi: 10.1080/10408369991239213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finn J T, Grunwald M E, Yau K-W. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:395–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bacskai B J, Hochner B, Mahaut-Smith M, Adams S R, Kaang B K, Kandel E R, Tsien R Y. Science. 1993;260:222–226. doi: 10.1126/science.7682336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hempel C M, Vincent P, Adams S R, Tsien R Y, Selverston A I. Nature (London) 1996;384:166–169. doi: 10.1038/384166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jurevicius J, Fischmeister R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:295–299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rich T C, Fagan K A, Nakata H, Schaack J, Cooper D M F, Karpen J W. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:147–161. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rich T C, Tse T E, Rohan J G, Schaack J, Karpen J W. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:63–77. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fagan K A, Schaack J, Zweifach A, Cooper D M F. FEBS Lett. 2001;500:85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trivedi B, Kramer R H. Neuron. 1998;21:895–906. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He T-C, Zhou S, DaCosta L T, Yu J, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2509–2514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orlicky D J, Schaack J. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:460–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans T, Smith M M, Tanner L I, Harden T K. Mol Pharmacol. 1984;26:395–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salomon Y, Londos C, Rodbell M. Anal Biochem. 1974;58:541–548. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas J M, Hoffman B B. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:907–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffmann R, Baillie G S, MacKenzie S J, Yarwood S J, Houslay M D. EMBO J. 1999;18:893–903. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellevuo K, Yoshimura M, Kao M, Hoffman P L, Cooper D M F, Tabakoff B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192:311–318. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarez R, Taylor A, Fazzari J J, Jacobs J R. Mol Pharmacol. 1981;20:302–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macphee C H, Reifsnyder D H, Moore T A, Lerea K M, Beavo J A. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:10353–10358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conti M, Nemoz G, Sette C, Vicini E. Endocrine Rev. 1995;16:370–389. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-3-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houslay M D, Sullivan M, Bolger G B. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;44:225–342. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svoboda K, Tank D W, Denk W. Science. 1996;272:716–719. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bridge J H, Smolley J R, Spitzer K W. Science. 1990;248:376–378. doi: 10.1126/science.2158147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leblanc N, Hume J R. Science. 1990;248:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.2158146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finch E A, Augustine G J. Nature (London) 1998;396:753–756. doi: 10.1038/25541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takechi H, Eilers J, Konnerth A. Nature (London) 1998;396:757–760. doi: 10.1038/25547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma H T, Patterson R L, van Rossum D B, Birnbaumer L, Mikoshiba K, Gill D L. Science. 2000;287:1647–1651. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akita T, Kenji Kuba K. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:697–720. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.5.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin A R, Fuchs P A. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1992;250:71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts W M, Jacobs R A, Hudspeth A J. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3664–3684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03664.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaggar J H, Porter V A, Lederer W J, Nelson M T. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C235–C256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.C235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinberg S F, Brunton L L. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:751–773. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen-Izu Y, Xiao R P, Izu L T, Cheng H, Kuschel M, Spurgeon H, Lakatta E G. Biophys J. 2000;79:2547–2556. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76495-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davare M A, Avdonin V, Hall D D, Peden E M, Burette A, Weinberg R J, Horne M C, Hoshi T, Hell J W. Science. 2001;293:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5527.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feliciello A, Gottesman M E, Avvedimento E V. J Mol Biol. 2001;308:99–114. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogreid D, Doskeland S O. Biochemistry. 1983;22:1686–1696. doi: 10.1021/bi00276a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harootunian A T, Adams S R, Wen W, Meinkoth J L, Taylor S S, Tsien R Y. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:993–1002. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.10.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.