Abstract

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are commonly prescribed to patients with a variety of inflammatory disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). GCs mediate their immunomodulatory effects through many different mechanisms and target multiple signaling pathways. The GC dexamethasone downmodulates innate and adaptive immune cell activation. IBD is the manifestation of a dysregulated immune response involving many different immune cells. Group 3 innate lymphocytes (ILC3s) have critical roles in mucosal inflammation. ILC3s secrete high levels of the cytokine IL-22, promoting epithelial proliferation, antimicrobial peptides and mucins. In this study, we examined the effects of dexamethasone on IL-22 production by ILC3s. We found that dexamethasone suppressed IL-23-mediated IL-22 production in human and mouse ILC3s. This was mediated in part through dexamethasone modulation of the NF-κB pathway. Inhibition of NF-κB signaling with a small molecule inhibitor also downmodulated IL-23- and IL-1β-mediated IL-22 production in ILC3s. These findings implicate NF-κB as a regulator of IL-22 in ILC3s and have likely repercussions on GC treatment of IBD patients.

Keywords: Innate lymphocytes, cytokines, glucocorticoids

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a grouping of chronic diseases caused by dysregulated immune responses within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (1). Lifelong treatment is required to minimize inflammation and, hopefully, improve quality of life. Although many new biologics have been developed that target specific aspects of mucosal biology, such as cytokines and immune cell trafficking (2), general immunosuppression via steroids is still often the first line of treatment for patients. Glucocorticoids (GCs) are one class of steroid used to suppress inflammatory cytokine production.

Numerous cytokines are upregulated in IBD patients, and these immune mediators are at least partially responsible for the inflammatory milieu, leading to ulceration and/or granulomas (3). The cytokine IL-22 is upregulated in both the sera and inflamed tissue of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) patients (4). Using experimental animal models of IBD, studies have shown that IL-22 is protective to tissues during IBD, through induction of epithelial and stem cell proliferation, antimicrobial peptides and mucins, which compose a mucosal barrier that shields the epithelium (5). Through effects on the epithelium, IL-22 also modulates the composition of the microbiome which can have an impact on the severity of IBD (6). In contrast, IL-22 has also been shown to be immunopathogenic in other IBD models, by causing hyperplasia and colonic thickening or increased inflammation (7, 8). IL-22 is a potential target for drug therapy, either directly or indirectly, by targeting the cytokine itself or upstream factors that regulate its production (9).

IL-22 is predominantly produced by CD4 T cells and group 3 innate lymphocytes (ILC3s) (10). ILC3s are rare immune cells that upon stimulation with IL-23 or IL-1β become activated and produce IL-22, as well occasionally as other factors such as IL-17 and GM-CSF (11). These cells can be found in mucosal tissues and have important roles in homeostatic barrier maintenance, infectious disease and IBD (12–16). IL-22 expression in ILC3s is primarily regulated by the STAT3 and aryl hydrocarbon (AHR) signaling pathways (17, 18), but other signaling pathways such as Notch and MAPK also contribute (19, 20). Understanding the pathways that regulate IL-22 biology is therefore important for developing therapies for many chronic inflammatory diseases.

GCs are a commonly used therapy for many chronic inflammatory diseases. GCs diffuse through the cell membrane to bind to glucocorticoid receptors (GR), activating or repressing gene transcription through several different mechanisms (21, 22). GRs can directly bind to GC response elements (GRE) encoded in the DNA, GRs can bind to and modulate other transcription factors, and GRs can perform composite binding to both DNA and other transcription factors. All nucleated cells express GRs, and the effects of GCs on many cell types have been well described (21). GCs can modulate cells of the gastrointestinal epithelium (23) and have pleiotropic effects on the immune system, including both immunosuppressive and inflammatory activities (21).

Dexamethasone is a prototypical synthetic GC and modulates the function of many types of immune cells. The effects of dexamethasone on T lymphocyte function are well described (21), however, it is not known if dexamethasone modulates the critical function of ILC3s or if dexamethasone regulates the cytokine IL-22. In this study, we show that the GC dexamethasone negatively regulates IL-22 production in homeostatic and activated mouse and human ILC3s. Dexamethasone did not modulate the IL-23 canonical signaling pathway of JAK2/STAT3, but did suppress phosphorylation of IκBα, an important regulator in NF-κB activation. Inhibition of NF-κB signaling with a small molecule inhibitor also downmodulated IL-23- and IL-1β-mediated IL-22 production in ILC3s. GC suppression of ILC3s may be an important component of their therapeutic mechanisms in chronic inflammatory disease patients.

Materials and Methods

Human ILC3s

Tonsils were received after being discarded from pediatric surgery at OU Children’s Hospital (Oklahoma City, OK) or from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (CHTN). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to the initiation of our studies.

Cell line

Clone B3, derived from an ILC3-like cell line, MNK-3 cells (24), was maintained in DMEM (Corning; Tewksbury, MA) with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gemini Bio-Products; West Sacramento, CA), 2 mM GlutaGro (Corning), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (GE Healthcare HyClone; Logan, UT), 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 10 mM HEPES (Corning), 50 μg/ml gentamycin (Amresco; Solon, OH), 100 U/ml penicillin (Gemini Bio-Products), 100 U/ml streptomycin (Gemini Bio-Products) and 10 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-7 and IL-15 (eBioscience; San Diego, CA or Peprotech; Rocky Hill, NJ).

Mice

Rag1−/− mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) (25). Mice were housed in an AAALAC-accredited Helicobacter-free rodent barrier facility. All studies were approved by the OUHSC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Human lymphocyte preparation

Tonsillar lymphocytes were isolated by passing minced tonsil pieces (approximately 1 mm) through a 70 μM cell strainer and washed with HBSS supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 U/ml streptomycin, 5 μg/ml gentamicin and 0.5 μg/ml amphotericin B (Corning). Tonsillar lymphocytes were isolated by layering a single cell suspension over a Ficoll gradient (GE Healthcare Life Sciences; Pittsburgh, PA) followed by centrifugation. After isolating cells from the interface, which were mostly leukocytes, RBCs were lysed. Cells were then washed in HBSS for three times to remove contaminating Ficoll. Tonsillar lymphocytes were aliquoted and stored in liquid nitrogen until future use.

Splenocyte preparation

Spleens were excised and single cell suspensions were made by disruption of the spleen on wire mesh using the plunge of a 3 ml syringe. Cells were centrifuged and the cell pellet was resuspended. Red blood cells were lysed in ACK lysis buffer (0.83% NH4Cl, 0.5% KHCO3, 0.5 μM EDTA) for 2 min and then neutralized with PBS or media. Cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion staining and a hemocytomer.

GC treatment and ILC activation

Cells (human lymphocytes or sorted ILCs, MNK-3 cells, splenocytes) were cultured in appropriate media and then stimulated with the indicated concentration of dexamethasone in DMSO (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) or DMSO as a control for 2 hrs. Cortisone, prednisone and fluticasone propionate were from Sigma. Cells were then stimulated with species-matched recombinant mouse or human IL-23 (eBioscience) (50 ng/ml) or mouse IL-1β (20 ng/ml, eBioscience). In some experiments, cells were treated prior to dexamethasone with the indicated dose of the GR antagonist, RU486 (mifepristone) (Sigma) or BAY11-7082 (Sigma).

Viability assay

Apoptosis was monitored by Annexin V and 7-AAD staining following manufacturers’ protocols (BD Biosciences or BioLegend). Cells were treated or not with dexamethasone and IL-23 and after 6 hrs, cells were centrifuged and the supernatant was removed and stored. Cell pellets were washed with PBS. Cells were surface stained to identify ILCs. Cells were then stained with Annexin V and 7-AAD. Stained cells were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry on a Stratedigm S1200Ex flow cytometer (Stratedigm, San Jose, CA) and data were analyzed using FlowJo v.9.6 (Tree Star; Ashland, OR).

Intracellular cytokine staining

Cells were treated with dexamethasone or cytokine as indicated in the presence of brefeldin A (BFA) (eBioscience) for 5 hrs. For human lymphocytes, cells were first stained with a fixable viability dye (eBioscience) and then surface stained to identify ILCs. Human cells or MNK-3 cells were intracellulary stained with an Ab that recognized both human and mouse IL-22 (clone IL22JOP, eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and then analyzed by flow cytometry.

ELISA

Mouse or human IL-22 ELISAs (Antigenix America; Huntington Station, NY) were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Real time RT-PCR

Cells were harvested in Trizol (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) or TriPure (Roche; Nutley, NJ) and RNA was prepared according to the manufacturers’ protocols. RNA was DNase treated (Roche) and cDNA was reverse transcribed using Transcriptor (Roche) with oligo dT as the primer. cDNA was used as template in a real time PCR reaction using ABI Taqman primer-probes sets on a ABI 7500 Fast real time PCR machine (Life Technologies). cDNA was semi-quantitated using the ΔΔCT method with Hprt (mouse) or HPRT (human) as an internal control for all samples.

Immuno blotting

After stimulation, cells were washed with PBS. Cells were lysed with TN1 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 125 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM sodium fluoride and 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (1.2 mM AEBSF, 0.46 μM aprotinin, 14 μM bestatin, 12.3 μM E-64, 112 μM leupeptin, 1.16 μM pepstatin) (Amresco; Solon, OH)) and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Enzo Life Sciences; Farmingdale, NY). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 4-15% gradient gel (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA). Proteins were transferred to an Immobilion-P PVDF membrane (EMD Millipore; Billerica, MA) using a wet transfer method. The protein-transferred membrane was blocked with 5% dry milk and then incubated with the manufacturers’ recommended concentration of primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Antibodies were: actin (Santa Cruz; Dallas, TX or Cell Signaling Technology (CST); Danvers, MA), GR (CST), phospho-GR (CST), STAT3 (CST), phospho-STAT3 (CST), IκBα (CST), phospho-IκBα (CST). Blots were then washed and incubated with the appropriate species-specific-HRP secondary antibody (1:1000) for 1 hr. Blots were developed using Pierce ECL2 Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA) and imaged using a FluorChemQ (Alpha Innotech; San Leandro, CA). For reblotting with another antibody, blots were stripped using a Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific) and then washed and re-blocked and performed with a new primary Ab as indicated above. Images were semi-quantitated using open source Image J software.

Statistical Analysis

Values are expressed as mean±SD. For two-way comparisons, a standard paired t test was used. For multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis was used. Significance was defined as a value of p≤0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.005 (***). Differences that were not significant (p>0.05) are marked as ns.

Results

Dexamethasone suppresses IL-23-mediated IL-22 production in human ILC3s

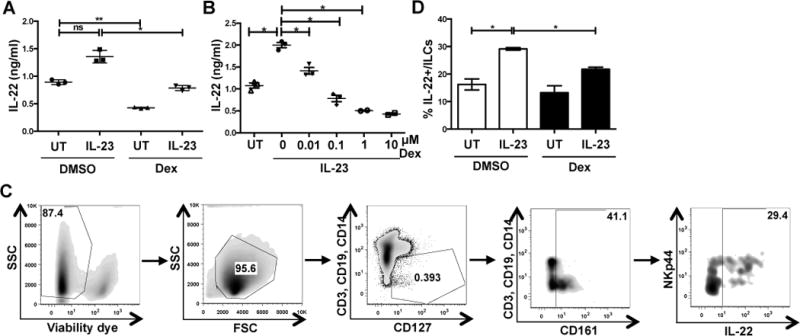

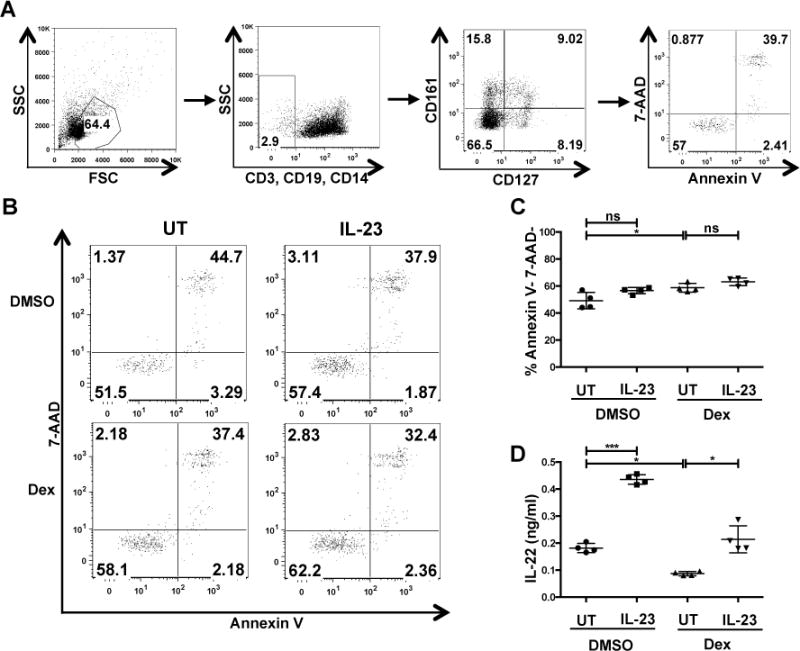

To initiate our studies on the effects of glucocorticoids on ILC3 function, we examined if dexamethasone modulated the capacity of the cytokine IL-23 to induce IL-22 production by ILCs. Lymphocytes isolated from discarded human tonsils were treated with 100 nM dexamethasone or vehicle control (DMSO) for 2 hrs and then stimulated with recombinant human IL-23 for 18 hrs. DMSO treated unstimulated cells secreted low levels of IL-22 as detected by ELISA, which were further decreased upon dexamethasone treatment (Fig 1A), suggesting that dexamethasone modulates homeostatic IL-22 production. Upon IL-23 stimulation, DMSO control cells secreted greater amounts of IL-22 compared to non-stimulated cells. However, although IL-23 stimulation increased IL-22 secretion from dexamethasone treated cells, they still secreted significantly less IL-22 than DMSO treated IL-23 stimulated cells (Fig 1A). This dexamethasone-mediated inhibition of IL-23-mediated IL-22 secretion was dependent on dexamethasone dose (Fig 1B), and remarkably partial suppression was still observed at 10 nM dexamethasone. 100 nM dexamethasone inhibited 100% of IL-23-mediated IL-22 production and is an optimal dose that saturates GR binding but has minimal off target effects. Therefore, this concentration was chosen for most of our studies. Dexamethasone inhibited IL-22 production in ILC3s, as the percent of ILC3s (Lin- CD127+ CD161+) that were IL-22+ by intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry were reduced in the presence of dexamethasone (Fig 1C-D). Unlike that reported for T cells or ILC2s (26, 27), dexamethasone did not affect cell viability, as no changes in ILC3 (Lin- CD127+ CD161) (Fig 2A) viability were detected in dexamethasone and/or IL-23 stimulated cells by Annexin V and 7-AAD staining (Fig 2B-C). We also measured secreted IL-22 from the exact cells we assayed viability on and found that as observed for a longer cytokine stimulation, dexamethasone downmodulated IL-23-mediated IL-22 production (Fig 2D).

Figure 1. Dexamethasone negatively modulates IL-22 production by human ILC3s.

(A-B) Human tonsillar lymphocytes were treated with DMSO or dexamethasone (100 nM or indicated dose) for 2 hrs followed by recombinant human IL-23 (50 ng/ml) stimulation for 18 hrs. Cell supernatants were analyzed for IL-22 secretion by ELISA. Shown are replicates from one experiment expressed as mean ±SD performed at least 3 times with similar results.

(C-D) Human tonsillar lymphocytes were treated as in A, in the presence of BFA for 5 hrs, and IL-22 was analyzed in ILCs (CD3- CD14- CD19- CD127+ CD161+) by intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry for IL-22. (C) Gating strategy for identification of ILC3s. (D) Summary of data from multiple donors. Data represent mean±SD of 4 independent experiments.

Figure 2. Dexamethasone does not affect human ILC3 viability.

Human tonsillar lymphocytes were treated with DMSO or 100 nM dexamethasone for 2 hrs and then stimulated with recombinant human IL-23 (50 ng/ml). After 6 hrs, cell death in ILCs (CD3- CD14- CD19- CD127+ CD161+) was assessed by Annexin V and 7-AAD staining. (A) Gating strategy to identify ILC3s. (B) Shown are the representative dot plots, (C) quantified viability data and (D) 6 hr IL-22 production from one of two experiments.

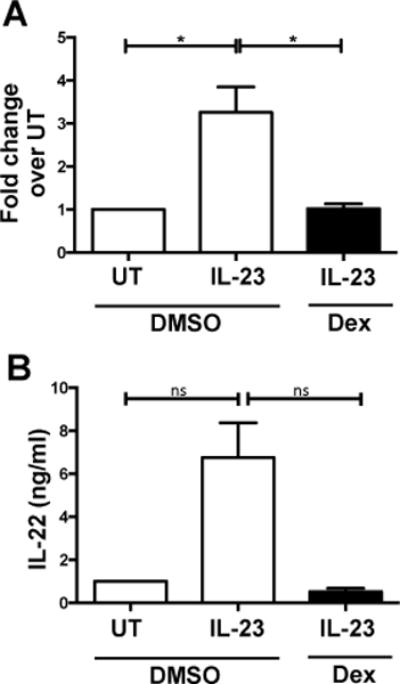

To specifically examine the effects of dexamethasone on ILCs, we purified human ILCs via cell sorting (Lin- CD127+), treated them with dexamethasone or DMSO for two hours and then stimulated the cells with IL-23 for 18 hrs. To examine if dexamethasone also affected IL-22 at a transcriptional level, we examined IL22 mRNA levels. Dexamethasone treatment significantly inhibited IL-23-mediated IL22 upregulation in the ILCs (Fig 3A). Secreted IL-22 was reduced, albeit not statistically, from IL-23-stimulated ILCs that were treated with dexamethasone compared to DMSO treated ILCs (Fig 3B). Thus, dexamethasone suppresses IL-22 production in human ILC3s under both homeostatic and IL-23-mediated inflammatory conditions via a direct effect on the ILCs.

Figure 3. Dexamethasone downregulates IL-22 production in purified human ILCs.

Human CD127+ ILCs were sort purified (CD3- CD14- CD19- CD127+), treated with DMSO or 100 nM dexamethasone for 2 hrs, then stimulated with recombinant human IL-23 (50 ng/ml) for 18 hrs and measured for (A) IL22 mRNA expression shown as fold change over untreated (UT) cells and (B) secreted production after 18 hrs of IL-23 stimulation. Shown are mean+SD from 4-5 experiments.

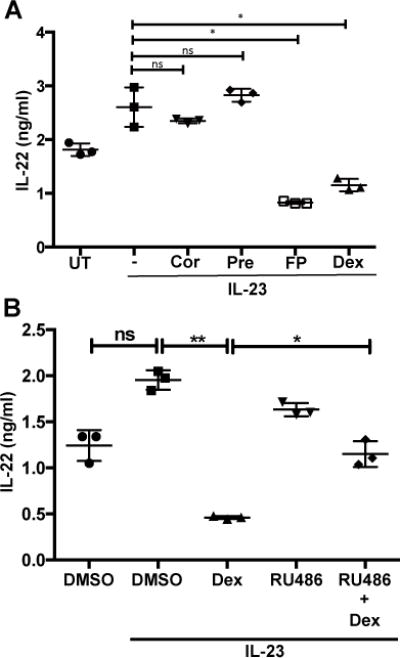

Dexamethasone-mediated inhibition of IL-22 production is through the glucocorticoid receptor (GR)

Dexamethasone is one of many GCs used for immunomodulatory therapies. We next examined if this effect is shared by other GCs, which would suggest suppression occurs through a conserved GR signaling pathway. We found that at the same concentration as dexamethasone, cortisone and prednisone did not suppress IL-23-mediated IL-22 upregulation, but fluticasone propionate (FP) did inhibit to a similar extent as dexamethasone (Fig 4A). Cortisone and prednisone are 5-25 times less potent than dexamethasone (28), which may account for their lack of suppressive activity.

Figure 4. Dexamethasone-mediated inhibition of IL-22 production is through the glucocorticoid receptor (GR).

(A) Human tonsillar lymphocytes were untreated (UT), or treated with 100 nM of cortisone (Cor), prednisone (Pre), fluticasone propionate (FP) or dexamethasone (Dex) for 2 hrs and then stimulated, where indicated, with recombinant human IL-23 (50 ng/ml). 18 hrs later, secreted IL-22 was analyzed by ELISA. Shown are mean±SD of 3 independent experiments.

(B) Human tonsillar lymphocytes cells were pretreated where indicated with 100 nM RU486 (a GR antagonist) for 15 min prior to the treatment of DMSO or dexamethasone (100 nM) for 2 hrs. Cells were then stimulated with recombinant human IL-23 (50 ng/ml) for 18 hrs. Cell supernatants were analyzed for IL-22 by ELISA. Shown are mean±SD of 3 independent experiments.

Most cellular effects of dexamethasone are through its interaction with the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), but GCs could have effects that are independent of GR signaling. In order to determine if dexamethasone effects were through its interaction with the GR, we examined if RU486 (also known as mifepristone), a GR antagonist (29), could antagonize dexamethasone-mediated inhibition of IL-22 production. Treatment of human tonsillar lymphocytes with an equimolar concentration of RU486 prior to dexamethasone treatment partially relieved some of the suppressive effects of dexamethasone on IL-23-mediated IL-22 production (Fig 4B) suggesting that dexamethasone negatively regulates IL-22 production through its interaction with GR. A slight decrease in IL-22 was noted with RU-486 and IL-23, in the absence of dexamethasone, and the GR antagonist may interfere with natural GCs produced by the cell or in the media that are involved in cytokine signaling. These data, along with ILC3 suppression by fluticasone propionate, suggest that dexamethasone suppresses IL-23-mediated IL-22 production through the GR.

Dexamethasone activates GR in ILC3s

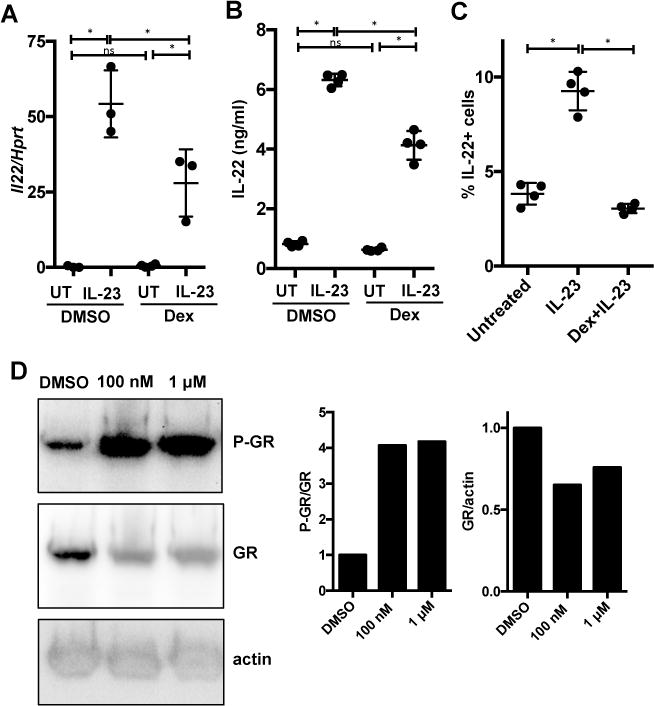

To examine if dexamethasone modulates GR activation, we examined phosphorylation of GR with and without dexamethasone treatment. As primary ILCs are rare and difficult to purify in sufficient quantities, we made use of a recently generated ILC3-like cell line, MNK-3, that was isolated from mouse fetal thymic immune precursors (24). These cells produce high levels of IL-22 upon stimulation with IL-23 and their use permitted both semi-quantification of transcript expression and visualization of cellular protein levels by immunoblot. Upon dexamethasone treatment and/or IL-23 stimulation, MNK-3 cells treated with dexamethasone compared to DMSO treated cells, had reduced levels of Il22 transcript, secreted less IL-22 or fewer cells producing IL-22 as measured by intracellular cytokine staining (Fig 5A-C). These data suggest that in MNK-3 cells dexamethasone does not completely inhibit IL-23-mediated Il22 mRNA or IL-22 protein levels but does have strong effects of the recruitment of new IL-22-producing cells. To examine GR levels and its activation in ILC3s, MNK-3 cells were treated with dexamethasone, or DMSO as a control, for 2 hrs. We found that dexamethasone treatment led to a reduction in total levels of GR, but an increase in the phosphorylation of GR (Fig 5D). This result suggests that dexamethasone activates GR in ILC3s.

Figure 5. Dexamethasone treatment phosphorylates the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in ILC3s.

(A-C) MNK-3 cells, a mouse ILC3-like cell line, were treated with DMSO or 100 nM dexamethasone for 2 hrs followed, where indicated, by recombinant mouse IL-23 stimulation (50 ng/ml) for 6 hrs (A), 18 hrs (B) or 5 hrs in the presence of BFA (C). (A) Cells were analyzed for Il22 mRNA expression by real-time semi-quantitative RT-PCR, (B) cell supernatants were analyzed for secreted IL-22 protein by ELISA and (C) the percent of cells IL-22+ was analyzed by intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry. Each point represents one well (n=3-4), horizontal line indicates mean, and error bars depict standard deviation. Shown are data from one representative experiment from 3 or more experiments.

(D) MNK-3 cells were treated with DMSO, 100 nM or 1μM dexamethasone for 2 hrs and then phosphorylated glucocorticoid receptor (GR), total GR and actin levels were analyzed by immunoblot. (Left) Shown is 1 representative of 2 independent blots. (Right) Semi-quantification of the bands in blots.

Dexamethasone inhibits IκBα activation in ILC3s

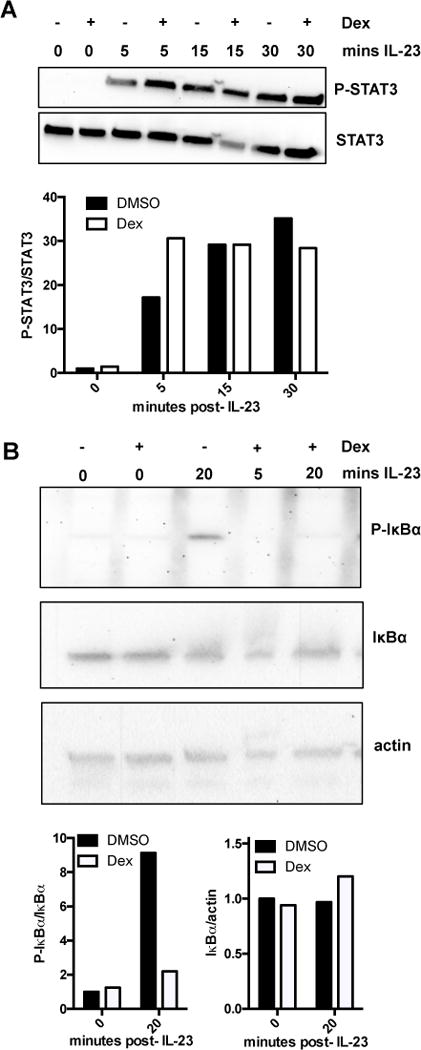

GCs modulate numerous distinct as well as intersecting signaling pathways in immune cells (21). The canonical signaling pathway induced by IL-23 is the JAK2/STAT3 pathway (30), with which dexamethasone modulation is not commonly associated. As such, we did not observe any changes in IL-23-mediated STAT3 phosphorylation after dexamethasone treatment of MNK-3 cells (Fig 6A). The ineffectiveness of dexamethasone on STAT3 phosphorylation has been reported for Th17 cells (31), suggesting a similar regulation in Th17 cells and ILC3s. As GCs inhibit the NF-κB pathway (21), and this transcription factor regulates the expression of a myriad of genes involved in immunity, including IL-22 (32–34), we examined if dexamethasone modulated this pathway and suppressed IL-23-mediated IL-22 production in ILC3s. Specifically, we examined IκBα as it controls an important regulatory step in NF-κB activation (33). IκBα binds NF-κB, sequestering it inactive in the cytoplasm. Upon phosphorylation of IκBα it disassociates from NF-κB and is targeted for proteasomal degradation, allowing NF-κB to translocate to the nucleus. IL-23 stimulation of MNK-3 cells led to a rapid increase in the phosphorylation of IκBα, which was suppressed by prior treatment of the cells with dexamethasone (Fig 6B). Thus, dexamethasone inhibits NF-κB activation in ILC3s.

Figure 6. Dexamethasone modulates NF-κB signaling in ILC3s.

(A) MNK-3 cells were treated with DMSO (−) or 100 nM dexamethasone (+) for 2 hrs and then stimulated with mouse recombinant IL-23 (50 ng/ml) for the time indicated. Levels of phosphorylated STAT3 (P-STAT3) or total STAT3 (STAT3) were analyzed by immunoblot. Shown are representative data from 1 of 2 experiments. Graph shows semi-quantification of bands.

(B) MNK-3 cells were treated with DMSO (−) or 100 nM dexamethasone (+) for 2 hrs and then stimulated or not with recombinant IL-23 (50 ng/ml) for 5 or 20 min. Levels of phosphorylated IκBα (P-IκBα), total IκBα (IκBα) or actin were analyzed by immunoblot. Shown are one set of representative blots and the experiment was performed 3 times with similar results. Graphs show semi-quantification of bands.

NF-κB activation is important for IL-23- or IL-1β-mediated IL-22 production by ILC3s

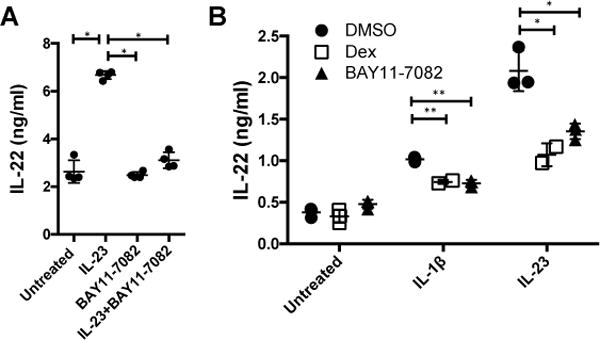

As dexamethasone modulated activation of IκBα, we questioned whether NF-κB signaling is important for IL-23-mediated production of IL-22 in ILC3s. Incubation of MNK-3 cells with BAY11-7082, an inhibitor of cytokine-induced IκBα phosphorylation (35), prior to IL-23 stimulation resulted in significant decreased secreted levels IL-23-mediated IL-22 (Fig 7A). As NF-κB activation is known to be critical for IL-1β signaling, we also examined the ability of dexamethasone or BAY11-7082 to suppress IL-1β-mediated production of IL-22 by ILC3s. We observed that treatment of Rag1−/− mouse splenocytes, where the major IL-22 producer has been shown to be ILCs (36), with BAY11-7082 prior to IL-1β stimulation reduced the secretion of IL-22 from the cells (Fig 7B). Dexamethasone treatment was also able to downregulate IL-1β-mediated IL-22 secretion (Fig 7B). Thus, inhibition of NF-κB signaling downregulated IL-23- or IL-1β-mediated IL-22 production by ILC3s.

Figure 7. Inhibition of NF-κB signaling downregulates IL-23- and IL-1β-mediated IL-22 production in ILC3s.

(A) MNK-3 cells or (B) Rag1−/− mouse splenocytes were treated with DMSO, 100 nM dexamethasone (dex) or 10 μM BAY11-7082 for 2 hrs and then stimulated with recombinant mouse IL-23 (50 ng/ml), IL-1β (20 ng/ml) or left untreated for 18 hrs. Secreted IL-22 was measured by ELISA. Each point represents one well (n=3-4), horizontal line indicates mean, and error bars depict standard deviation. Shown are data from one representative experiment from 3 experiments.

Discussion

In this study, we find that the commonly prescribed GC, dexamethasone, downregulates cytokine-induced IL-22 production in mouse and human ILCs. These cells were predominantly ILC3s, as IL-22 secretion is a defining characteristic of this ILC subset. We primarily studied IL-23-mediated IL-22 production, but also observed that dexamethasone downmodulated IL-1β-mediated IL-22 production as well. Dexamethasone had no detectable effect on the canonical IL-23-mediated STAT3 signaling pathway but did downmodulate NF-κB signaling. This is one pathway identified and given the broad mechanisms of action of dexamethasone, other signaling pathways may also be targeted by the drug in ILC3s. Ultimately, understanding how GCs modulate innate immune cell function is critical for understanding how GC therapies affect patients afflicted with chronic inflammatory diseases.

We predict that GC therapy will decrease IL-22 levels in patients with IBD or other chronic inflammatory diseases, which has both potentially positive and negative consequences. This may be beneficial, as long-term IL-22 production in experimental animal models is associated with hyperplasia and colorectal cancer (7, 37). However, IL-22 is also important in normal immune homeostasis and if reduced too low, may have detrimental effects on microbiome or epithelial barrier integrity. IL-22 deficient mice have few phenotypes in the absence of inflammation (6, 38), suggesting that IL-22 is not absolutely necessary for a healthy life in specific pathogen-free (SPF) housing. However, humans are constantly exposed to potential infection by mucosal pathogens and therapeutics that alter IL-22 levels may have detrimental effects.

IL-22 can be protective or pathogenic in experimental mouse models of IBD (7, 8, 13, 14). In dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-mediated colitis IL-22 is protective (13). This model involves the DSS-mediated destruction of the colonic epithelium, which leads to the displacement of luminal commensal bacteria to the lamina propria, causing activation of the innate immune system. Local or systemic delivery of dexamethasone can protect mice from DSS-mediated colitis (39, 40). As dexamethasone targets most cells, not only those of the immune system, it also has effects on mucosal barrier itself. Future work will carefully dissect the role of GCs on ILC3s, other immune cells, and the mucosal epithelium.

Our study focuses on dexamethasone, a man-made GC first synthesized in the 1950s. Natural GCs, such as cortisol, are produced at low levels by the adrenal gland and induced during stress responses. Under physical or psychological stress, increased levels of natural GCs may modulate IL-22 production by ILC3s, as well as other functions of the cells. We have observed that dexamethasone inhibits IL-1β-, but not IL-23-, mediated GM-CSF production, but do not readily detect IL-17 from these activated cells (data not shown). This may have long term effects on patient’s mucosal health and may explain some of the purported links between stress and IBD flares (41, 42).

Identification of signaling pathways that regulate activation of ILC3s and/or IL-22 production is important for basic immunology, but critical for translational immunology. Recently, IL-18 stimulation of ILC3s was shown to involve NF-κB signaling, including binding of p65 to the IL22 promoter (34). Our study now shows that IL-23 stimulation also leads to NF-κB activation through phosphorylation of IκBα. GC treatment prevented this phosphorylation, and GCs also suppressed IL-23-mediated IL-22 production. Inhibition of NF-κB signaling using a pharmacological inhibitor reduced IL-23-mediated IL-22 production by ILC3s. Thus, NF-κB activation in ILC3s through different cytokines contributes to IL-22 production.

ILC3s are a principal source of IL-22, a critical cytokine in mucosal immune responses. Our findings on GCs and ILC3 interactions implicate NF-κB as an important regulator of IL-22 production. GC-mediated suppression of ILC3s may be an important component of their therapeutic mechanisms in chronic inflammatory disease patients. Understanding the different signaling pathways that each contribute to cytokine production is imperative to development of new and improvement of existing therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mark L. Lang for discussion and reading of the manuscript. We thank Drs. P. Digoy, C.F. Barañano and E. Woodson (OUHSC Department of Otorhinolaryngology) and CHTN for providing discarded tonsils and Drs. James R. Carlyle and David S.J. Allan for providing us with MNK-3 cells and clone B3. We acknowledge the OMRF FACS core and the OUHSC Flow Cytometry and Imaging Core for cell sorting and analysis.

Footnotes

Research in the Zenewicz lab is supported by an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (14SDG18700043), National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number P20GM103447 (PI: D. Akins, OUHSC), subaward A199F from 5 U19 AI062629 (PI K.M. Coggeshall, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation), an Oklahoma Center for the Advancement for Science & Technology Health Research grant (HR 13-003) and the Oklahoma Center for Adult Stem Cell Research grant, a program of TSET, to LAZ. S.S. was supported in part by subaward A179F from 5 U19 AI062629.

References

- 1.de Souza HS, Fiocchi C. Immunopathogenesis of IBD: current state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:13–27. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neurath MF. Current and emerging therapeutic targets for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:269–278. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:329–342. doi: 10.1038/nri3661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andoh A, Zhang Z, Inatomi O, Fujino S, Deguchi Y, Araki Y, Tsujikawa T, Kitoh K, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Takayanagi A, Shimizu N, Fujiyama Y. Interleukin-22, a member of the IL-10 subfamily, induces inflammatory responses in colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:969–984. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizoguchi A. Healing of intestinal inflammation by IL-22. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1777–1784. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zenewicz LA, Yin X, Wang G, Elinav E, Hao L, Zhao L, Flavell RA. IL-22 deficiency alters colonic microbiota to be transmissible and colitogenic. J Immunol. 2013;190:5306–5312. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamanaka M, Huber S, Zenewicz LA, Gagliani N, Rathinam C, O’Connor W, Jr, Wan YY, Nakae S, Iwakura Y, Hao L, Flavell RA. Memory/effector (CD45RB(lo)) CD4 T cells are controlled directly by IL-10 and cause IL-22-dependent intestinal pathology. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1027–1040. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eken A, Singh AK, Treuting PM, Oukka M. IL-23R+ innate lymphoid cells induce colitis via interleukin-22-dependent mechanism. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:143–154. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabat R, Ouyang W, Wolk K. Therapeutic opportunities of the IL-22-IL-22R1 system. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:21–38. doi: 10.1038/nrd4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dudakov JA, Hanash AM, van den Brink MR. Interleukin-22: immunobiology and pathology. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:747–785. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artis D, Spits H. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2015;517:293–301. doi: 10.1038/nature14189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng Y, Valdez PA, Danilenko DM, Hu Y, Sa SM, Gong Q, Abbas AR, Modrusan Z, Ghilardi N, de Sauvage FJ, Ouyang W. Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat Med. 2008;14:282–289. doi: 10.1038/nm1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zenewicz LA, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Stevens S, Flavell RA. Innate and adaptive interleukin-22 protects mice from inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity. 2008;29:947–957. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugimoto K, Ogawa A, Mizoguchi E, Shimomura Y, Andoh A, Bhan AK, Blumberg RS, Xavier RJ, Mizoguchi A. IL-22 ameliorates intestinal inflammation in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:534–544. doi: 10.1172/JCI33194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickert G, Neufert C, Leppkes M, Zheng Y, Wittkopf N, Warntjen M, Lehr HA, Hirth S, Weigmann B, Wirtz S, Ouyang W, Neurath MF, Becker C. STAT3 links IL-22 signaling in intestinal epithelial cells to mucosal wound healing. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1465–1472. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raffatellu M, George MD, Akiyama Y, Hornsby MJ, Nuccio SP, Paixao TA, Butler BP, Chu H, Santos RL, Berger T, Mak TW, Tsolis RM, Bevins CL, Solnick JV, Dandekar S, Baumler AJ. Lipocalin-2 resistance confers an advantage to Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium for growth and survival in the inflamed intestine. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:476–486. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu J, Heller JJ, Guo X, Chen ZM, Fish K, Fu YX, Zhou L. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates gut immunity through modulation of innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2012;36:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo X, Qiu J, Tu T, Yang X, Deng L, Anders RA, Zhou L, Fu YX. Induction of innate lymphoid cell-derived interleukin-22 by the transcription factor STAT3 mediates protection against intestinal infection. Immunity. 2014;40:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chea S, Perchet T, Petit M, Verrier T, Guy-Grand D, Banchi EG, Vosshenrich CA, Di Santo JP, Cumano A, Golub R. Notch signaling in group 3 innate lymphoid cells modulates their plasticity. Sci Signal. 2016;9:ra45. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaf2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seshadri S, Allan DSJ, Carlyle JR, Zenewicz LA. Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin negatively modulates ILC3 function through perturbation of IL-23-mediated MAPK signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006690. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cain DW, Cidlowski JA. Immune regulation by glucocorticoids. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:233–247. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desmet SJ, De Bosscher K. Glucocorticoid receptors: finding the middle ground. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1136–1145. doi: 10.1172/JCI88886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer A, Gluth M, Weege F, Pape UF, Wiedenmann B, Baumgart DC, Theuring F. Glucocorticoids regulate barrier function and claudin expression in intestinal epithelial cells via MKP-1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;306:G218–228. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00095.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allan DS, Kirkham CL, Aguilar OA, Qu LC, Chen P, Fine JH, Serra P, Awong G, Gommerman JL, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Carlyle JR. An in vitro model of innate lymphoid cell function and differentiation. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:340–351. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson RS, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaioannou VE. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuosto L, Cundari E, Gilardini Montani MS, Piccolella E. Analysis of susceptibility of mature human T lymphocytes to dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1061–1065. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walford HH, Lund SJ, Baum RE, White AA, Bergeron CM, Husseman J, Bethel KJ, Scott DR, Khorram N, Miller M, Broide DH, Doherty TA. Increased ILC2s in the eosinophilic nasal polyp endotype are associated with corticosteroid responsiveness. Clin Immunol. 2014;155:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaikh S, Verma H, Yadav N, Jauhari M, Bullangowda J. Applications of Steroid in Clinical Practice: A Review. ISRN Anesthesiology. 2012;2012:11. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung-Testas I, Baulieu EE. Inhibition of glucocorticosteroid action in cultured L-929 mouse fibroblasts by RU 486, a new anti-glucocorticosteroid of high affinity for the glucocorticosteroid receptor. Exp Cell Res. 1983;147:177–182. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(83)90282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parham C, Chirica M, Timans J, Vaisberg E, Travis M, Cheung J, Pflanz S, Zhang R, Singh KP, Vega F, To W, Wagner J, O’Farrell AM, McClanahan T, Zurawski S, Hannum C, Gorman D, Rennick DM, Kastelein RA, de Waal Malefyt R, Moore KW. A receptor for the heterodimeric cytokine IL-23 is composed of IL-12Rbeta1 and a novel cytokine receptor subunit, IL-23R. J Immunol. 2002;168:5699–5708. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banuelos J, Shin S, Cao Y, Bochner BS, Morales-Nebreda L, Budinger GR, Zhou L, Li S, Xin J, Lingen MW, Dong C, Schleimer RP, Lu NZ. BCL-2 protects human and mouse Th17 cells from glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. Allergy. 2016;71:640–650. doi: 10.1111/all.12840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Q, Lenardo MJ, Baltimore D. 30 Years of NF-kappaB: A Blossoming of Relevance to Human Pathobiology. Cell. 2017;168:37–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008;132:344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Victor AR, Nalin AP, Dong W, McClory S, Wei M, Mao C, Kladney RD, Youssef Y, Chan WK, Briercheck EL, Hughes T, Scoville SD, Pitarresi JR, Chen C, Manz S, Wu LC, Zhang J, Ostrowski MC, Freud AG, Leone GW, Caligiuri MA, Yu J. IL-18 Drives ILC3 Proliferation and Promotes IL-22 Production via NF-kappaB. J Immunol. 2017;199:2333–2342. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierce JW, Schoenleber R, Jesmok G, Best J, Moore SA, Collins T, Gerritsen ME. Novel inhibitors of cytokine-induced IkappaBalpha phosphorylation and endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression show anti-inflammatory effects in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21096–21103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonnenberg GF, Monticelli LA, Elloso MM, Fouser LA, Artis D. CD4(+) lymphoid tissue-inducer cells promote innate immunity in the gut. Immunity. 2011;34:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huber S, Gagliani N, Zenewicz LA, Huber FJ, Bosurgi L, Hu B, Hedl M, Zhang W, O’Connor W, Jr, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Booth CJ, Cho JH, Ouyang W, Abraham C, Flavell RA. IL-22BP is regulated by the inflammasome and modulates tumorigenesis in the intestine. Nature. 2012;491:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature11535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zenewicz LA, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Karow M, Flavell RA. Interleukin-22 but not interleukin-17 provides protection to hepatocytes during acute liver inflammation. Immunity. 2007;27:647–659. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang S, Ermann J, Succi MD, Zhou A, Hamilton MJ, Cao B, Korzenik JR, Glickman JN, Vemula PK, Glimcher LH, Traverso G, Langer R, Karp JM. An inflammation-targeting hydrogel for local drug delivery in inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:300ra128. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren K, Yuan H, Zhang Y, Wei X, Wang D. Macromolecular glucocorticoid prodrug improves the treatment of dextran sulfate sodium-induced mice ulcerative colitis. Clin Immunol. 2015;160:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernstein CN, Singh S, Graff LA, Walker JR, Miller N, Cheang M. A prospective population-based study of triggers of symptomatic flares in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1994–2002. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao X, Cao Q, Cheng Y, Zhao D, Wang Z, Yang H, Wu Q, You L, Wang Y, Lin Y, Li X, Wang Y, Bian JS, Sun D, Kong L, Birnbaumer L, Yang Y. Chronic stress promotes colitis by disturbing the gut microbiota and triggering immune system response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720696115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]