Abstract

Introduction

Left ventricular (LV) strain by speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) is a comparatively new prognostic marker. Meta-analyses relating LV strain by STE to outcomes have been conducted in selected patient-based populations with established or suspected cardiovascular (CV) diseases. However, the evidence related to population-based studies of community-dwelling individuals is uncertain. The aim of this study is to provide a comprehensive systematic review and analysis of the current available literature regarding LV strain by STE as a predictor of adverse outcomes in population-based studies.

Methods and analyses

Thesaurus and text-word searching will be used to search two online databases (MEDLINE and EMBASE) and additional sources will be identified from citation metrics and reference lists’ search. Dual search results’ screening, data extraction and quality assessment will be performed. Cohort studies of community/population-based samples who have had STE and followed up longitudinally for mortal and morbid events, and published in English and peer-reviewed journals will be included. Primary outcome will be all-cause mortality whereas secondary outcomes will be composite cardiac and CV end points. Risk of bias will be assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale of cohort studies that will be modified as appropriate. Any arising discrepancies will be discussed and resolved through consensus.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required as this is a protocol for a systematic review. The findings of this study will be presented at scientific conferences and published in a peer-reviewed journal. Any amendments to the protocol will be documented and updated in the PROSPERO registry.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018090302.

Keywords: speckle tracking echocardiography, community dwelling individuals, left ventricular strain, mortality, cardiovascular disease

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review will evaluate the evidence related to the incremental prognostic value of left ventricular (LV) strain by speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) in relation to mortality and cardiovascular events in community-dwelling individuals or population-based samples known to be at low risk relative to selected diseased populations.

The results of this systematic review will add to the existing evidence on the utility of STE-based LV strain as a measure of cardiac function and risk, and influence its use in longitudinal population-based studies.

Because of the anticipated heterogeneity in results/presentation of results and/or study design across a limited number of existing studies, there may be a limited scope for meta-analysis. When meta-analysis is possible, heterogeneity in associations between studies may be difficult to explain.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality worldwide and accounts for 31% of deaths.1 Assessment of left ventricular (LV) global systolic function is central in evaluating prognosis, as well as in determining therapeutic strategies in CVD.2 Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is a simple and widely used parameter that is most commonly measured by echocardiography.3 Reduced LVEF is known to be associated with unfavourable outcomes in populations with established CVD4–7 but also in people without known CVD.8 9 However, this parameter suffers from a number of inherent limitations including load dependency, low reproducibility and geometric assumptions.3 Furthermore, its inverse association with outcomes varies considerably across the spectrum of LVEF, being greatest in moderately to severely impaired LV systolic function.7

LV strain imaging, tissue Doppler based and speckle-tracking based, has emerged as a powerful and sensitive tool allowing an accurate quantification of myocardial mechanics including longitudinal, circumferential and radial shortening/lengthening, and torsion.10 Strain, a dimensionless index, is defined as a change in length of a myocardial segment: strain (ε) =ΔL/L0, where ΔL=change in length and L0=original length.3 10 11 The major limitation of tissue Doppler-derived strain (natural strain) is the angle dependency of measurements and this technique has been superseded by speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) (Lagrangian strain).10 As the term implies, STE is based on the analysis of myocardial features (speckles) on grayscale B-mode images that are generated by ultrasound interference patterns within the myocardium.10–12 These speckles are tracked frame by frame during the cardiac cycle providing a sensitive and objective measure of global and regional myocardial function (ie, Lagrangian strain).10–12 Unlike tissue Doppler imaging (TDI), STE is angle independent, can differentiate active from passive motion13 and has been validated in an experimental setting against sonomicrometry14 as well as in a clinical setting against cardiac magnatic resonance imaging (CMR).15

STE-based LV strain imaging has been shown to have an independent and additive prognostic value over conventional echocardiographic measures in a number of studies of diseased populations. These included patients with chronic16 17 or acute18heart failure (HF) including both people with reduced19 20 and preserved21 LVEF. Further, STE-based LV strain imaging has prognostic utility after acute myocardial infarction (MI)22 23 and in chronic ischaemic cardiomyopathy.24 Importantly, STE-based LV strain especially global longitudinal strain (GLS) has a potential value in detecting subclinical LV systolic dysfunction (LVSD) when LVEF is within normal limits.3 Indeed, the most common clinical setting is the prediction of cardiotoxicity in patients receiving cancer therapy.25 GLS has also shown an association with unfavourable outcomes in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis26 and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy27 with preserved LVEF. Alterations in GLS despite preserved LVEF have been demonstrated in populations with risk factors that predispose to CVD, including ageing,28 diabetes mellitus (DM),29 hypertension30 and obesity,31 and may be the earliest marker of LVSD.

Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses relating LV strain by STE to outcomes have been conducted in selected patient-based samples with established32–35 or established plus suspected CVD.36 However, no systematic review has been performed of studies which have recruited community-dwelling individuals or population-based samples, who were not selected on the basis of disease or clinical status, and are known to be at low risk compared with selected diseased populations, and the utility of STE in this setting is uncertain. This may be important since selecting samples based on disease status can introduce bias.37 Consequently, we sought to investigate whether LV strain measured by STE is associated with risk of total and cardiovascular (CV) mortality and morbidity independent of conventional risk factors in population-based samples. We therefore proposed to carry out a systematic review and, where possible, meta-analysis of the current literature relating LV strain by STE to mortality and CV morbidity in the general population.

Methods

Reporting

This systematic review will be conducted and reported in adherence with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement38 and PRISMA protocols.39

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria which relate to the type of study design, population and measurement procedure are summarised in table 1. Studies will only be included if they assess the prospective association of LV strain with at least one of the prespecified outcomes in community-dwelling individuals who were not selected on the basis of disease or clinical status (table 1). To be eligible for inclusion, studies will be required to include a statement regarding the ethical approval or adherence to an appropriate standard (such as the Declaration of Helsinki).40

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria of the systematic review

| Type of study design |

|

| Type of participants/population |

|

| Type of procedure |

|

| Measured parameters (exposure) |

|

| Type of outcomes |

|

| Year of publication |

|

| Languages |

|

| Publication status |

|

Outcomes

The primary outcome will be all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes will be (1) composite CV end points, including any combination of CV mortality, coronary heart disease (CHD) events (MI, unstable angina, angina/ischaemia requiring emergent hospitalisation or revascularisation), HF hospitalisation, new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF), life-threatening arrhythmia, recorded automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD) shocks, stroke, transit ischaemic attack or peripheral arterial disease with arterial revascularisation procedure or (2) composite cardiac end point, including any combination of CV mortality, CHD events (MI, unstable angina, angina/ischaemia requiring emergent hospitalisation or revascularisation), HF hospitalisation, new-onset AF, life-threatening arrhythmia, recorded AICD shocks. Tertiary outcomes will be any individual secondary end point included in the composite cardiac or CV end point.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria will be as follows: (1) studies not meeting the inclusion criteria; (2) case–control studies, cross-sectional studies or randomised controlled trials which lack a placebo limb; (3) studies in unrepresentative samples of the general population (eg, clinic populations) or patients with established/known CVD (eg, patients with MI or HF); (4) LV strain measured by TDI or by another imaging modality (eg, CMR); (5) studies with end points that do not match those specified in this review (eg, LV remodelling) or (6) abstracts, reviews, conference proceedings or letters to the editor.

Search strategy

Electronic searches

This literature search will be performed systematically in the following online databases: MEDLINE (1946 to present) and EMBASE Classic + EMBASE (1947 to present) via OvidSP interface. Research has suggested that these databases are likely to be sufficient to identify relevant studies.41 A combination of thesaurus and text-word searching will be used to comprehensively extract all relevant articles. Boolean operators (AND/OR), proximity operators and truncation commands will be used when necessary to narrow the search to the relevant literature. The effectiveness of the search strategy will be tested and refined accordingly. The relevant thesaurus terms will be developed first for the MEDLINE database and will be checked and modified for EMBASE database as appropriate. A modified version of SIGN filters for observational studies will be used to capture the required studies (ie, population-based studies only). No time or language limit will be applied to the search and the final date on which the search will be carried out will be stated. Databases’ search strategy is shown in online supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2018-023346supp001.pdf (213.8KB, pdf)

Additional sources

Other sources will be identified by thoroughly searching the reference lists of all relevant articles. We will also search the citation metrics of those articles using Web of Science Core Collection for additional studies.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in designing the protocol of this systematic review.

Data collection and analyses

Study selection

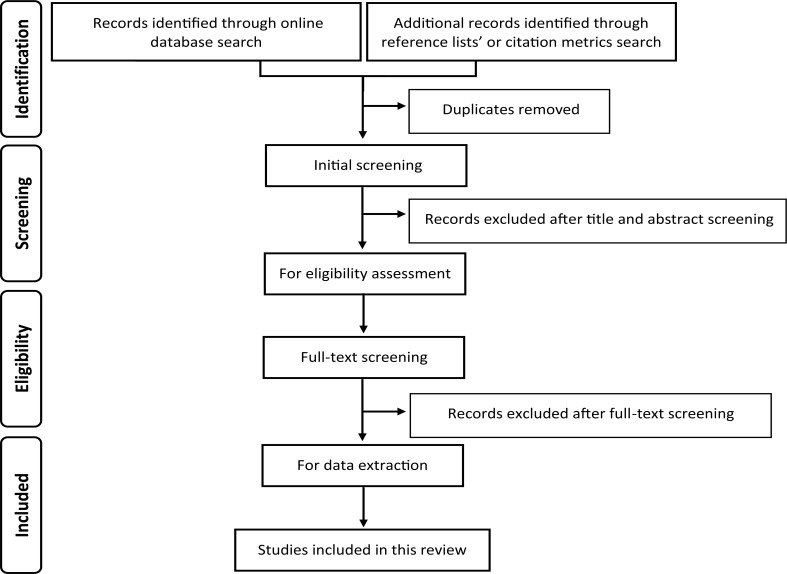

The search results from each database will be retrieved and merged using reference manger software (ie, in a single EndNote library). Duplicates will be identified using the command ‘Find Duplicates’ and will be removed before screening is commenced. Titles and abstracts will then be screened for eligibility by two researchers working independently and irrelevant articles will be dismissed. Full texts of potentially eligible articles will be retrieved and double screened. A predefined eligibility form (see online supplementary file 2) will be applied to the identified studies to determine whether the inclusion criteria are met. Reasons for exclusions will be recorded. Discrepancies will be reviewed and resolved through consensus of all reviewers. The study selection process will be summarised using PRISMA flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrates the study selection process following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.38

bmjopen-2018-023346supp002.pdf (200KB, pdf)

Data extraction

We will use a predefined data extraction form (see online supplementary file 2) which will be piloted on a sample of included studies to ensure that all relevant information is captured. Data will be extracted by two researchers independent of each other and any discrepancies will be discussed in order to achieve consensus. The following data will be extracted: (1) citation details including title, type and year of publication; (2) study and participant details including name, region and design of the study, sample size, demographics (age, sex ethnicity) and follow-up duration; (3) clinical variables including the presence or absence of hypertension, DM, dyslipidaemia, smoking status and known CVD; (4) exposure details including the hardware and the software used for the acquisition and analysis as well as details regarding the measured LV strain including the direction of the analysed myocardial motion, the echocardiographic images used for the analysis, the number of LV segments involved, the number of sonographers used to perform the analysis and if intraobserver or interobserver variability was reported; (5) details of outcomes (ie, all-cause mortality, composite CV and cardiac end points) including how these were ascertained; (6) statistical methods used, for example, Cox proportional hazards regression, as well as statistics related to the association of interest, for example, HR (or rate ratio), related measures of precision (ie, 95% CI or SE) and statistical significance (p-value) and (7) information related to adjustment for potential confounders.

Quality assessment

Quality of included studies will be assessed using a preassigned scale (Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale of cohort studies)42 that will be modified according to the review question to capture all relevant sources of potential bias (see online supplementary file 3).43 Two reviewers will judge the quality of each study by considering the following criteria: representativeness of the cohort, completeness of collection of potential confounders, follow-up duration, assessment of outcome and the reliability of exposure (ie, LV strain). The total quality score will be reported as the average of the two researchers’ scores ranging from 0, the lowest quality score, to 7, the highest quality score. Studies will be included irrespective of the quality assessment, but sensitivity analyses will be carried out to test the impact of removing the studies with the lowest quality score one at a time.

bmjopen-2018-023346supp003.pdf (170.1KB, pdf)

This systematic review does not study a treatment comparison, and hence quality of evidence assessment based on strict GRADE guidelines (ie, Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations) is not directly applicable. However, we will employ relevant components of a GRADE evaluation, namely quality of study, consistency and effect size in evaluating the strength of evidence; the issue of generalisability is dealt with through the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Data synthesis

Descriptive summary of the characteristics and findings of the included studies will be provided in tables. We anticipate that there may be a limited scope for meta-analysis due to differences in the method of analysis and the reporting of results across studies. If the included studies are sufficiently homogeneous and report the same statistics (eg, comparable HRs), a quantitative synthesis using random effect meta-analysis will be used to pool the results of the association of interest. Based on our expectation, we will likely to use the HR and 95% CI as an effect estimate for presenting the results and will present the data graphically in forest plots.

The degree of heterogeneity will be assessed using Higgins Thompson I2 test44 45 and Cochran’s Q test.46 If data allow, we will perform subgroup analyses or metaregression to explore prespecified potential sources of between-study heterogeneity: (1) study quality, (2) variation in exposure measurement (eg, vendors and type of strain (ie longitudinal, circumferential or radial)) and (3) variation in CV and cardiac outcomes definition. Although it may not be possible, we plan to do subgroup analyses by sex and age categories (<65 and ≥65 years). Possible publication bias will be assessed using a Funnel plot.47

Discussion

STE is increasingly and widely used in clinical practice. However, this technology suffers from inherent limitations, being influenced by technical as well as clinical factors.13 High-quality images with adequate frame rates are required and there is limited evidence comparing different imaging modalities (two-dimensional and three-dimensional echocardiography). Further, this technology is vendor specific: differences between vendors in data processing and analysis limit its generalisability and contribute to the present lack of normal values.13 48 STE-derived strain values may also be influenced by clinical factors including age, sex and race.13 48

This systematic review will identify and synthesise evidence regarding STE-derived measures as prognostic indicators of mortality and CV events in population-based/community-dwelling individuals. The restriction to studies not selected on the basis of disease or clinical status should minimise potential collider bias due to index case selection. The review will also potentially highlight known limitations of STE. This analysis will add to evidence on the utility of STE as a measure of cardiac function and risk and influence its use (or otherwise) in longitudinal population-based studies and community-dwelling samples.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol is for conducting a systematic review and hence no ethical approval is required. The findings of this review will be presented at scientific conferences and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LAS is the guarantor of the review who drafted the protocol and registered it in PROSPERO. LAS and AH contributed in developing the eligibility criteria, search strategy, and data extraction and quality assessment strategy. AH and CP critically reviewed and amended the protocol. RH provided statistical advice and critically reviewed and commented on the protocol.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: AH works in a unit that receives support from the UK Medical Research Council (Programme Code MC_UU_12019/1) and also receives support from the British Heart Foundation (PG/15/75/31748, CS/15/6/31468, CS/13/1/30327), and the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre. CP receives support from the British Heart Foundation (CS/15/6/31468). LA is supported by a scholarship grant from Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.WHO. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). WHO (updated May 2017) http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/ (accessed 12 Mar 2018).

- 2.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2129–200. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potter E, Marwick TH. Assessment of left ventricular function by echocardiography: the case for routinely adding global longitudinal strain to ejection fraction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11:260–74. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohn JN, Johnson GR, Shabetai R, et al. Ejection fraction, peak exercise oxygen consumption, cardiothoracic ratio, ventricular arrhythmias, and plasma norepinephrine as determinants of prognosis in heart failure. The V-HeFT VA Cooperative Studies Group. Circulation 1993;87:VI5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes JA, Mehta D, Ip J, et al. Predictors of long-term survival in patients with malignant ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:1054–60. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00046-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottdiener JS, McClelland RL, Marshall R, et al. Outcome of congestive heart failure in elderly persons: influence of left ventricular systolic function. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:631–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-137-8-200210150-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis JP, Sokol SI, Wang Y, et al. The association of left ventricular ejection fraction, mortality, and cause of death in stable outpatients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:736–42. 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00789-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hays AG, Sacco RL, Rundek T, et al. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction and the risk of ischemic stroke in a multiethnic population. Stroke 2006;37:1715–9. 10.1161/01.STR.0000227121.34717.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeboah J, Rodriguez CJ, Stacey B, et al. Prognosis of individuals with asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation 2012;126:2713–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.112201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mor-Avi V, Lang RM, Badano LP, et al. Current and evolving echocardiographic techniques for the quantitative evaluation of cardiac mechanics: ASE/EAE consensus statement on methodology and indications endorsed by the Japanese Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24:277–313. 10.1016/j.echo.2011.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nesbitt GC, Mankad S, Oh JK, Jk O. Strain imaging in echocardiography: methods and clinical applications. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;25(Suppl 1):9–22. 10.1007/s10554-008-9414-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mondillo S, Galderisi M, Mele D, et al. Speckle-tracking echocardiography: a new technique for assessing myocardial function. J Ultrasound Med 2011;30:71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collier P, Phelan D, Klein A. A test in context: Myocardial strain measured by speckle-tracking echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1043–56. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langeland S, D’hooge J, Wouters PF, et al. Experimental validation of a new ultrasound method for the simultaneous assessment of radial and longitudinal myocardial deformation independent of insonation angle. Circulation 2005;112:2157–62. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.554006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amundsen BH, Helle-Valle T, Edvardsen T, et al. Noninvasive myocardial strain measurement by speckle tracking echocardiography: validation against sonomicrometry and tagged magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:789–93. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nahum J, Bensaid A, Dussault C, et al. Impact of longitudinal myocardial deformation on the prognosis of chronic heart failure patients. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;3:249–56. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.910893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang KW, French B, May Khan A, et al. Strain improves risk prediction beyond ejection fraction in chronic systolic heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000550 10.1161/JAHA.113.000550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho GY, Marwick TH, Kim HS, et al. Global 2-dimensional strain as a new prognosticator in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:618–24. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mignot A, Donal E, Zaroui A, et al. Global longitudinal strain as a major predictor of cardiac events in patients with depressed left ventricular function: a multicenter study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:1019–24. 10.1016/j.echo.2010.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sengeløv M, Jørgensen PG, Jensen JS, et al. Global longitudinal strain is a superior predictor of all-cause mortality in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:1351–9. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah AM, Claggett B, Sweitzer NK, et al. Prognostic importance of impaired systolic function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and the impact of spironolactone. Circulation 2015;132:402–14. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hung CL, Verma A, Uno H, et al. Longitudinal and circumferential strain rate, left ventricular remodeling, and prognosis after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1812–22. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ersbøll M, Valeur N, Mogensen UM, et al. Prediction of all-cause mortality and heart failure admissions from global left ventricular longitudinal strain in patients with acute myocardial infarction and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:2365–73. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertini M, Ng AC, Antoni ML, et al. Global longitudinal strain predicts long-term survival in patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:383–91. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.970434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thavendiranathan P, Poulin F, Lim KD, et al. Use of myocardial strain imaging by echocardiography for the early detection of cardiotoxicity in patients during and after cancer chemotherapy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2751–68. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yingchoncharoen T, Gibby C, Rodriguez LL, et al. Association of myocardial deformation with outcome in asymptomatic aortic stenosis with normal ejection fraction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:719–25. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.977348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, Pozios I, Haileselassie B, et al. Role of global longitudinal strain in predicting outcomes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2017;120:670–5. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.05.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuznetsova T, Herbots L, Richart T, et al. Left ventricular strain and strain rate in a general population. Eur Heart J 2008;29:2014–23. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen MT, Sogaard P, Andersen HU, et al. Global longitudinal strain is not impaired in type 1 diabetes patients without albuminuria: the Thousand & 1 study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:400–10. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narayanan A, Aurigemma GP, Chinali M, et al. Cardiac mechanics in mild hypertensive heart disease: a speckle-strain imaging study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:382–90. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.811620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong CY, O’Moore-Sullivan T, Leano R, et al. Alterations of left ventricular myocardial characteristics associated with obesity. Circulation 2004;110:3081–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147184.13872.0F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma C, Chen J, Yang J, et al. Quantitative assessment of left ventricular function by 3-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography in patients with chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis. J Ultrasound Med 2014;33:287–95. 10.7863/ultra.33.2.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris DA, Ma XX, Belyavskiy E, et al. Left ventricular longitudinal systolic function analysed by 2D speckle-tracking echocardiography in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis. Open Heart 2017;4:e000630 10.1136/openhrt-2017-000630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shetye A, Nazir SA, Squire IB, et al. Global myocardial strain assessment by different imaging modalities to predict outcomes after ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A systematic review. World J Cardiol 2015;7:948–60. 10.4330/wjc.v7.i12.948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalam K, Otahal P, Marwick TH. Prognostic implications of global LV dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global longitudinal strain and ejection fraction. Heart 2014;100:1673–80. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanton T, Leano R, Marwick TH. Prediction of all-cause mortality from global longitudinal speckle strain: comparison with ejection fraction and wall motion scoring. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:356–64. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.862334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flanders WD, Eldridge RC, McClellan W. A nearly unavoidable mechanism for collider bias with index-event studies. Epidemiology 2014;25:762–4. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;350:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vergnes JN, Marchal-Sixou C, Nabet C, et al. Ethics in systematic reviews. J Med Ethics 2010;36:771–4. 10.1136/jme.2010.039941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartling L, Featherstone R, Nuspl M, et al. The contribution of databases to the results of systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:127 10.1186/s12874-016-0232-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. Newcastle-ottawa quality assessment scale, cohort studies. 2014.

- 43.Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:666–76. 10.1093/ije/dym018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cochran WG. The comparison of percentages in matched samples. Biometrika 1950;37:256–66. 10.1093/biomet/37.3-4.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002 10.1136/bmj.d4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yingchoncharoen T, Agarwal S, Popović ZB, et al. Normal ranges of left ventricular strain: a meta-analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2013;26:185–91. 10.1016/j.echo.2012.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023346supp001.pdf (213.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023346supp002.pdf (200KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023346supp003.pdf (170.1KB, pdf)