Abstract

Objectives

To test whether social ties play any roles in mitigating depression and anxiety, as well as in fostering mental health among young men living in a poor urban community.

Setting

A cohort of all young men living in an urban slum in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh.

Participants

All men aged 18–29 years (n=824) living in a low-income urban community at the time of the survey.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Unspecified psychological morbidity measured using the General Health Questionnaire, 12-item (GHQ-12), where lower scores suggest better mental status.

Results

The GHQ scores (mean=9.2, SD=4.9) suggest a significant psychological morbidity among the respondents. However, each additional friend is associated with a 0.063 SD lower GHQ score (95% CI −0.106 to −0.021). Between centrality measuring the relative importance of the respondent within his social network is also associated with a 0.103 SD lower GHQ score (95% CI −0.155 to −0.051), as are other measures of social network ties. Among other factors, married respondents and recent migrants also report a better mental health status.

Conclusions

Our results underscore the importance of social connection in providing a buffer against stress and anxiety through psychosocial support from one’s peers in a resource-constraint urban setting. Our findings also suggest incorporating a social network and community ties in designing mental health policies and interventions.

Keywords: mental health, public health, social network, social determinants

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our analyses take advantage of a census of young men in a resource-constraint low-income urban community in Bangladesh to establish the roles a social network and community ties play in determining better mental health outcomes.

The measurement of the social network is based on a roster-based approach where friendship connections for all possible pairs of respondents are carefully assessed and validated.

We take advantage of a locally adopted General Health Questionnaire, 12-item to assess unspecified mental health outcomes along with detailed socioeconomic characteristics of our respondents.

Cross-sectional data limit causal interpretations and cannot rule out the reverse causality of otherwise robust relationships, and community ties through friendships can capture only limited aspects of the respondents’ social network.

Introduction

Mental illness and disorders refer to ‘abnormal thoughts, perceptions, emotions, behaviour and relationships with others’.1 Mental illness contributes about 7.1% to global disease burden, and the cost of mental disorders such as depression can be enormous.2 3 Over a person’s lifetime, psychological disorders can adversely affect one-third of the global population.4 As of 2010, close to 900 million people were estimated to suffer from certain mental health issues, including depression, anxiety and substance abuse.5 The burden of mental health is also likely to increase with growing urbanisation in low/middle-income countries.6 7 Poor neighbourhoods and low-income communities potentially offer more stressful environments for urban citizens.8 Hence, one can infer that a larger share of the global mental health burden will be borne by lower-income populations living in challenging environments in newly urbanised low/middle income nations. This is further compounded by the social stigma and general misinformation associated with mental health symptoms, resulting in low psychosocial care seeking in low/middle-income countries.9

Social capital can be multifaceted, and its definitions vary in the literature as they aim to capture the different aspects of social engagements for an individual.10 Social capital encompasses civic engagement, trust, reciprocity and certain norms. Moreover, it can both be a structural feature of the community or group and be owned by an individual to rely on and exploit to command over resources to ensure his or her well-being.11 12 The horizontal nature of ties, for example, friendship network and community embeddedness, is considered a defining feature of one’s social capital, and prior literature typically associates resulting social capital with socially desirable health outcomes.13

A growing consensus reveals that the quality of social ties and deeper social embeddedness are important determinants of mental health.14–16 Lack of social ties has been found to be a risk factor for some mental health indicators.17–20 By ensuring attachment and buffer, a social network and community ties can have both extrinsic and intrinsic values for an individual’s mental or psychological well-being.21 Prior studies have shown the positive roles social connection can play in lowering depressive episodes.20 22 Depressive symptoms are also less likely to manifest in people who are more central within the group they belong.23 Mental state of mind, like happiness, can also better in people with social networks that are closer in terms of geographical distance.19

In the context of Bangladesh, social networks have been found to contribute to health service delivery in both rural and urban areas.24 25 However, we have limited information on how social ties and network properties can determine mental health outcomes in urban Bangladesh and similar other low-income contexts. One’s social network has been found to have a strong association with positive mental health outcomes. However, these studies have been conducted mostly in developed countries by taking advantage of large, often longitudinal, cohort studies and population-level data.19 20 22 23 We intend to contribute to the growing literature on social network as a determinant of mental health by exploiting a community-level census of young men in a slum in Dhaka.

Method

Study design

We followed a cross-sectional study design based on individual respondents from a census of young men living in an urban slum at the time of the survey (n=824). The census allowed us to enumerate friendship ties along with directions between any two respondents among possible 339 076 ties. We also collected mental health outcome measures along with the detailed socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents.

Study setting

We conducted our study in a particular but otherwise typical urban community in Dhaka, namely, Vashantek. The entire Vashantek slum was geographically divided into four subdivisions with a total population of around 31 000 or about 5500 households. We chose to work in a particular subdivision and conducted a census of all men aged between 18 and 29 years. The study was part of a larger project, which focused on gender norms, risky sexual behaviour and mental health within this particular population. These topics often focused on adolescent or female populations. Hence, we chose postadolescent young men in a low-income urban community as the study population to provide some novel and unique perspectives to the relevant literature. We collected baseline information on a number of socioeconomic variables and detailed social network information on all the targeted respondents. The site and the setting met the necessary criteria for usual social network analyses (SNAs).26

Sample and sampling technique

We collected information on all men aged between 18 and 29 in our targeted site. Initially, we listed all the households in the study community with men who fit the age criteria. We asked each household whether a man, aged 18–29 years, lived in that household. We followed up with their full names, contact information and availability for a more detailed survey afterwards. We found a total of 942 potential respondents from 790 households through this initial listing process. After thoroughly training the data collectors and pretesting the questionnaire, we sent nine data collectors to conduct the surveys. We used skilled enumerators who had prior experience in a mobile-based quantitative survey through SurveyCTO. The enumerators conducted the interviews in 26 days during the month of December 2016.

We collected demographic, economic, sexual practice and friendship information using a structured questionnaire. We excluded some of the respondents who moved out of the slum between the initial household listing and the follow-up survey. We also found households that had a potential respondent who lived outside the community but was previously listed as a household member. We also excluded individuals with communication impairments and two respondents who refused to provide a written consent. The final cohort consisted of 824 young men aged 18–29 years living in our study area. We performed all analyses on this sample.

Patient and public involvement statement

No patients were involved in designing the study or developing the research questions, nor were they involved in analysing or interpreting the findings. The study was conducted on a community-based sample of individuals who met the prespecified criteria. We would discuss some of the general implications of the study findings through workshops as well as through a series of radio shows to help address mental health problems affecting young men in Dhaka.

Measures of mental well-being

We used the 12-question version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), an often-used survey-based tool that measures the population morbidity of non-psychotic and minor psychiatric disorders, to assess the mental well-being of individuals, where a higher score generally suggests a poor mental health outcome. GHQ-12 was implemented and validated widely in different contexts in both developed and low/middle-income countries, including Bangladesh.27 28 Because of its precise and concise nature and validity in the context of Bangladesh, we considered this tool to be appropriate for our study to assess any non-specific psychiatric morbidity among the respondents.29 We estimated Cronbach’s α, and a value of 0.83 suggests high internal consistency. We further performed exploratory factor analysis, and high individual variance for each factor suggested high reliability of the score in our sample. The detailed item-wise responses are reported in online supplementary appendix A.

bmjopen-2017-020180supp001.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

Social network analysis parameters

For the SNA, we asked each respondent to name his close friend(s) in the community and state where they lived (particular landmark/household identifier in the slum). After confirming the proper identification of all the close friends mentioned by the respondents, we constructed a 824×824 square sociomatrix showing direct friendship ties with a value of 1 or 0.30 We then used the network analysis software Pajek to analyse the data set. We estimated different social network parameters for each of our respondents to measure the embeddedness and centrality of each respondent within the friendship network. These measures captured richer aspects of the social network of the respondents (for definitions of the different social network parameters, see online supplementary appendix B).31 32 For robustness check and sensitivity analyses, we used non-linear versions of some of our centrality measures because of the over-representation of zeros in our sample, which indicates the absence of any ties between individuals.20 We also estimated some additional measures of the nature of the social network at individual levels to perform further sensitivity analyses (see online supplementary appendix C).

Socioeconomic characteristics

Given the observational nature of our study, we controlled for various socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents. These factors could potentially confound our results, and we included them all in our multivariable analyses. Some of these factors were also important and can capture community embeddedness and social support aspects of a person’s life that could influence psychosocial well-being, such as marital status and birth in the same community. We further collected information on the age of the respondent, and his education and current occupation. We also profiled the wealth status of the respondent’s households. We used a wealth index called Equity Tool which generated comparable results across different contexts.33 This tool was validated for Bangladesh and consists of seven questions in its latest update as of 2014. We chose the urban wealth scores and urban wealth quintile for our study.

Statistical analyses

To assess the relationship between mental well-being and social ties, we ran different regression models with different social network measures. We included the socioeconomic characteristics in all the regression models and separately analysed the coefficients on these additional controls. For the multivariable analyses, we used robust regression models to correct the possible violation of the standard Gauss-Markov assumptions (see online supplementary appendix D).34 We standardised both the mental health outcomes and the continuous variables on the right-hand side in the regression models and estimated the beta coefficients. We further used ordered probit analyses for some additional robustness checks (see online supplementary appendix C). In the outcome variable, GHQ-12 scores were discrete in nature and hence were prone to violation of the basic normality conditions. Ordered probit models relaxed these assumptions (see online supplementary appendixes C and D). All econometric analyses were performed using Stata/MP V.15.0.

Findings

Socioeconomic characteristics

We present the basic socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the respondents in table 1. The average age of the respondents is 24, with an SD of 3.6. About 44% of the respondents report living in the study community since birth. Interestingly, 52% of the respondents are married at the time of the survey. The respondent group also has low educational level as 45% report that they have achieved either not the primary educational level or lower. Their average schooling is about the same as those found in nationally representative household surveys.35

Table 1.

Summary statistics

| Mean (SD) | |

| Age, years | 23.6 (3.6) |

| Currently married, % | 52.2 (50.0) |

| Born in Vashantek, % | 44.2 (49.7) |

| Education, % | |

| No formal education | 83 (10.1) |

| Primary incomplete | 290 (35.2) |

| Primary complete | 106 (12.9) |

| Secondary incomplete | 206 (25.0) |

| Secondary complete/above | 139 (16.9) |

| Equity score | −0.016 (0.230) |

| Wealth quintile, % | |

| First | 61 (7.4) |

| Second | 325 (39.4) |

| Third | 418 (50.7) |

| Fourth | 16 (1.9) |

| Fifth | 4 (0.5) |

| Occupations, % | |

| Driver | 138 (16.8) |

| Service sector | 125 (15.2) |

| Student | 109 (13.2) |

| Business/shop owner | 100 (12.1) |

| Construction worker/carpenter/wall painter | 88 (10.9) |

| Daily labour | 58 (7.0) |

| Rickshaw puller/van puller | 43 (5.2) |

Based on surveys of 824 respondents. Equity index is based on ownership of selected assets (namely, refrigerator, television, almirah/wardrobe and electric fan) and household building materials. The wealth quintiles are based on equity scores with Bangladesh urban specific cut-offs. For occupations, ‘other’ category is not included in the table.

According to the generalisable equity score, with a mean of −0.016 and SD of 0.230, majority of our respondents come from second and third wealth quintiles, with very few (only 2.5%) from the top two wealth quintiles. We find a considerable variation in occupations that the respondents are engaged in, namely, driving, service in construction sectors and running small businesses. About 13% of the respondents report being students at tertiary-level educational institutions.

Mental health status

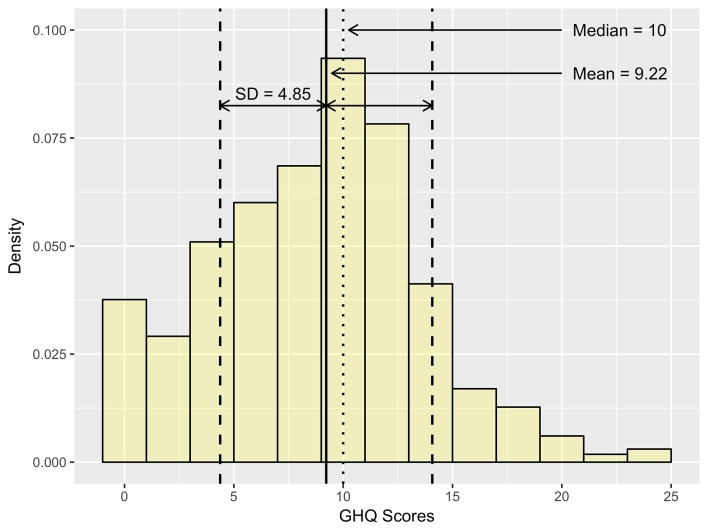

We present both distribution and summary statistics for the mental health status of the respondents in figure 1. We have found a considerable variation in GHQ-12 outcomes, which range from 0 to 25. The average GHQ-12 score is about 9.2 with an SD of 4.9. We have further assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the results reject the null hypothesis of normality. This result is natural given the discrete nature of GHQ-12 scoring, and we have further tested the robustness of our results using an ordered probit model that takes into account the discrete nature of our scoring (see online supplementary appendix C).

Figure 1.

Distribution of GHQ-12 scores. Based on 824 respondents. Here, we report the non-standardised GHQ scores. The mean is shown as the vertical solid line, and the median is shown as the vertical dotted line. GHQ is the aggregate of 12 questions with possible values of 0, 1, 2 and 3. The scores of all 12 questions are added to measure the composite score for a respondent. GHQ, General Health Questionnaire.

Social network analyses

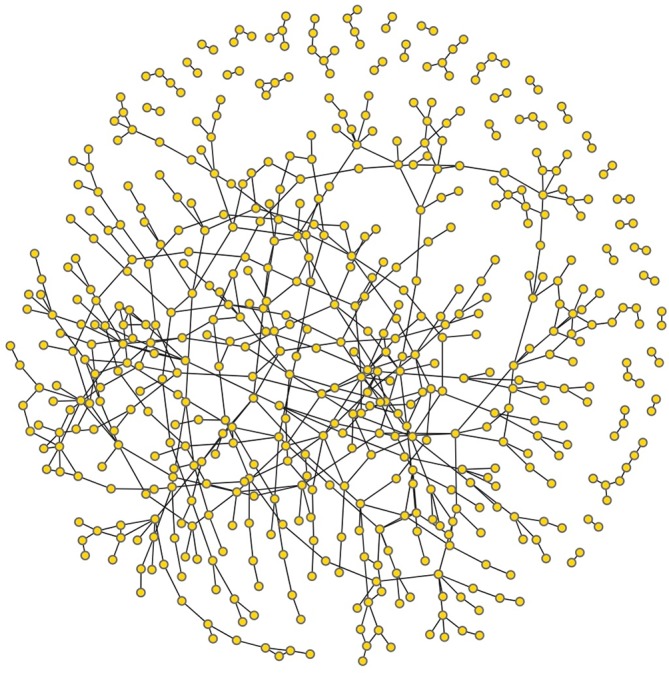

A visual inspection of the social network suggests that the respondents can belong to one of the three broad types of components (see figure 2): the largest component (n=452 or 55%), 37 smaller self-contained components with sizes between 2 to 7 friends (n=105 or 13%) and 267 respondents (32%) who have not mentioned anybody in the community as a friend, or nobody in the community has mentioned them as a friend (see table 2). They are entirely isolated individuals in our target population with zero friendship ties in the community. On average, our sample has 1.6 ties per respondent, including those who have reported no friendship tie in the community.

Figure 2.

Visualisation of the friendship network of the 824 young men of Vashantek. Here we show the social network graph for 824 respondents. Each node represents an individual respondent. The connector shows the friendship ties between two respondents. There are 267 respondents who are completely isolated (not included in the figure). The largest component consists of 450 respondents who are all connected with each other through intermediate ties. We also have 37 smaller components with smaller networks.

Table 2.

Social network characteristics of the respondents

| Mean | SD | |

| Respondents in each component, % | ||

| Large connected group | 54.6 | |

| Smaller groups | 12.7 | |

| Isolated with no referrals in any direction | 32.4 | |

| No of friends, % | ||

| 0 | 32.4 | |

| 1 | 26.3 | |

| 2 | 17.1 | |

| 3 | 11.0 | |

| 4 | 6.4 | |

| 5 | 3.9 | |

| 6 or more | 2.8 | |

| Average no of friendship ties | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Average Centrality Scores | ||

| Closeness centrality | 0.034 | 0.031 |

| Betweenness centrality | 0.00000662 | 0.000024 |

| Eigenvector centrality | 0.004 | 0.034 |

Based on 824 respondents. Each respondent reports the friendship ties within the community. The large connected group includes the biggest component where all subjects are connected with intermediate ties. Centrality measures are estimated using Pajek.

The average closeness centrality score is 0.034 for this network of 824 men (with an SD of 0.031, see table 2). The average betweenness centrality score for this network of 824 men is 6.6×10–6 (with an SD of 24.0×10–6) with an overall betweenness centralisation of 0.0003. We further estimate the average eigenvector centrality for the respondents which is equal to 0.004 (with an SD of 0.034). The overall eigenvector centralisation of the network is 0.0071. An average eigenvector (Bonacich power) centrality of 0.004 suggests that, on average, men in this network do not hold very prestigious positions with fairly low variation.

Association between mental well-being and social networks

The results from our multivariable regression analyses, which assess the association between mental health outcome (standardised GHQ scores) and individuals’ social network parameters, are presented in table 3. All the continuous variables are standardised. In column 1 of table 3, we find that compared with an isolated respondent with no community friendship tie, a respondent belonging to a small component has a 0.098 SD lower GHQ score (95% CI −0.327 to 0.131). Moreover, a respondent belonging to the larger component has a 0.117 SD lower GHQ score (95% CI −0.274 to 0.041).

Table 3.

Multivariable association between mental health outcomes and social network

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Component type | |||||

| Disconnected | Base | ||||

| Small | −0.098 (−0.327 to 0.131) | ||||

| Large | −0.117 (−0.274 to 0.041) | ||||

| No of friend(s) | −0.063*** (−0.106 to −0.021) | ||||

| Closeness centrality (standardised) | −0.053 (−0.124 to 0.018) | ||||

| Betweenness centrality (standardised) | −0.103*** (−0.155 to −0.051) | ||||

| Eigenvalue centrality (standardised) | −0.068*** (−0.103 to −0.033) | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.012 (−0.013 to 0.037) | 0.011 (−0.014 to 0.035) | 0.012 (−0.013 to 0.037) | 0.011 (−0.014 to 0.035) | 0.014 (−0.011 to 0.038) |

| Education | |||||

| No formal education | Base | Base | Base | Base | Base |

| Primary incomplete | −0.333** (−0.622 to −0.043) | −0.315** (−0.602 to −0.027) | −0.326** (−0.616 to −0.037) | −0.320** (−0.609 to −0.030) | −0.339** (−0.631 to −0.048) |

| Primary complete | −0.450*** (−0.777 to −0.124) | −0.437*** (−0.763 to −0.112) | −0.443*** (−0.771 to −0.115) | −0.447*** (−0.774 to −0.120) | −0.444*** (−0.773 to −0.115) |

| Secondary incomplete | −0.269* (−0.574 to 0.035) | −0.267* (−0.570 to 0.035) | −0.267* (−0.572 to 0.037) | −0.272* (−0.576 to 0.033) | −0.277* (−0.583 to 0.029) |

| Secondary complete or above | −0.114 (−0.452 to 0.223) | −0.105 (−0.441 to 0.230) | −0.114 (−0.452 to 0.223) | −0.125 (−0.462 to 0.211) | −0.131 (−0.470 to 0.208) |

| =1 if born outside Vashantek | −0.169** (−0.312 to −0.025) | −0.184** (−0.328 to −0.041) | −0.167** (−0.311 to −0.024) | −0.182** (−0.325 to −0.040) | −0.163** (−0.305 to −0.022) |

| =1 if currently married | −0.190** (−0.367 to −0.013) | −0.198** (−0.375 to −0.022) | −0.188** (−0.364 to −0.011) | −0.179** (−0.353 to −0.004) | −0.171* (−0.346 to 0.004) |

| Equity score (standardised) | −0.030 (−0.108 to 0.048) | −0.028 (−0.106 to 0.049) | −0.030 (−0.108 to 0.048) | −0.029 (−0.107 to 0.048) | −0.031 (−0.108 to 0.047) |

| Occupation fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 824 | 824 | 824 | 824 | 824 |

| R-squared | 0.036 | 0.047 | 0.036 | 0.043 | 0.038 |

The outcome variable is the standardised GHQ score in all five specifications. A higher GHQ score suggests worse mental health outcomes. The robust 95% CIs are reported in parentheses. We also control for occupations, which are not reported here.

*P<0.1, **P<0.05, ***P<0.01.

GHQ, General Health Questionnaire.

In the next model in column 2 of table 3, we find that mental health outcomes are systematically better with higher degrees of ties or number of friends. Having an additional friend is associated with a 0.063 SD lower GHQ score (95% CI −0.106 to −0.021). In the next three columns, we include different measures of centralities that retain all the controls. We find that a 1 SD higher all-closeness centrality score of a respondent is associated with a 0.053 SD lower GHQ score (95% CI −0.124 to 0.018, see column 3 in table 3). We find similar results for betweenness and eigenvalue centralities. Respondents with a 1 SD higher betweenness centrality score report about a 0.103 SD lower GHQ score (95% CI −0.155 to −0.051) and respondents with a 1 SD higher eigenvalue centrality score report about a 0.068 SD lower SHQ score (95% CI −0.103 to −0.033), controlling for other factors.

In all the five specifications, we include the socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents as controls or possible confounding factors. The association between mental health outcomes and other covariates is quite suggestive. We find that mental health worsens with age, about 0.012 SD higher with each additional year; however, while the point estimates are quite robust across different models, they are not very precise. More educated respondents report a lower GHQ score, so more educated respondents typically have better mental health status. Interestingly, respondents born in the community have better mental health status. Respondents who are currently married have 0.17–0.20 SD lower GHQ scores, and coefficient values are typically significant. We also find higher wealth as measured by the equity score, which is associated with a lower GHQ score or better mental health status.

Discussion

Our findings indicate the importance of social relations in determining mental well-being in resource-constrained contexts. Social ties are important components of a much broader idea of social capital, and observed outcomes can be associated with both the cognitive aspect of social bonding and the constructivist dimension of local social institutions.20 Hence, our results further highlight the importance of the social determinants of health in the context of mental health, a topic that has gained importance in both academic and policy literature in recent times.13 18 36

Our results show that young men with better social ties and higher community embeddedness and network report better mental health. We have used a number of different measures of social network parameters at an individual level that are typical of a person’s connectedness in his immediate community. While this captures a particular aspect of a person’s position in a broad spectrum of social capital that he can accumulate over time, our estimates are robust and suggest that connection with one’s peer from his community is a strong predictor of his mental health status.

Additionally, we should highlight the overall high average GHQ-12 score for our sample from the general population. For example, in the context of Bangladesh, previous researchers have found a GHQ-12 score of 20 with an SD of 3 among diagnosed mental patients.27 While clinical diagnoses of disorders require closer scrutiny and assessment by mental health professionals, such high score suggests a potentially high psychosocial morbidity associated with a high level of stress, anxiety and possibly depression. Although we have focused on only one neighbourhood in Dhaka, the study area is not peculiar or remarkable in any observational way, suggesting a broader implication and generalisability. In general, urban areas and youth populations are prone to isolation and can suffer from psychological distresses and psychoses.36

Social capital can influence one’s psychological well-being in a number of ways, and our study can only speculate the possible channels through which social ties can affect mental health in our study population.21 A social network can help individuals access material resources, such as loans, grants and health services.12 We have found that the respondents in our sample primarily rely on family members for their financial needs and community practitioners and informal care providers such as salespersons in local pharmacies for health services. This result suggests, within our context, that the social network promotes mental health primarily through socioemotional supports and recreational activities. However, identifying the exact nature of different channels requires further study and specific tools to measure different pathways through which social ties can alter mental health outcomes.

Given the cross-sectional nature of our study, we cannot claim causality in our findings. More specifically, it is possible that the association primarily picks up selection bias, where people with certain psychosocial traits are self-selected into the social structure typified by higher social ties and centrality, resulting in reverse causality that we cannot completely rule out given the observational nature of the study. However, we include a set of socioeconomic factors that are possible confounders of the mental health outcomes in our empirical models and we block these influences by controlling them in all our empirical models.37

Also, using GHQ-12 to measure mental health outcomes limits our study, as this questionnaire is not a clinical tool and captures a unidimensional unspecified psychological morbidity.29 Hence, this scale measures only the respondents’ actual mental health status with some measurement errors. This limits the total variation that we are able to explain using our empirical models. We also capture important social ties, namely, friends in the community and age group. The respondents can have social ties and a network outside the community as well as through social media. Such measurement errors lead to downward bias and smaller coefficients (in absolute terms), as one can see in all our models. So our estimates can be considered lower bounds for the true effects of social ties on the mental well-being of the respondents.

Despite these limitations, the findings presented here enhance our understanding of the social network determinants of mental health in an exciting population. The postadolescent young population is particularly important because, Bangladesh, like many low/middle-income countries in the world, remains and will remain largely young for another generation or so. High youth unemployment and underemployment rates can put a strain on men owing to traditional gender expectations.38 In this context, isolation and social disconnectedness can contribute to poorer mental health, luring male youth to violence, which has become a concern locally in recent times. Thus, our findings have important implications in understanding mental health outcomes and policies that address psychosocial health issues of young men and highlight the importance of social connection and ties in determining mental health in the postadolescent population in low/middle-income countries.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ARa and MS conceived this study. ARa led the analysis with guidance from NRB, ARi and MS. NRB led the collection and analyses of social network data with guidance from ARa. ARi managed the overall data collection and preliminary analyses with guidance from ARa and MS. ARa wrote the first draft and the final manuscript with contribution from MS. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by WOTRO Science for Global Development of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) under grant number W 08,560.007.

Disclaimer: The funding source did not play any role in designing the study or collecting, analysing or interpreting the data or preparing this manuscript and deciding to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board at the James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University reviewed and approved both the proposal and all the data collection protocols.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi: 10.5061/dryad.320bv7b.

References

- 1. WHO. Mental disorders. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs396/en/ (cited 29 Sep 2017).

- 2. Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet 2015;386:2145–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61340-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:171–8. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:476–93. 10.1093/ije/dyu038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 2013;382:1575–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferlander S. The importance of different forms of social capital for health. Acta Sociol 2007;50:115–28. 10.1177/0001699307077654 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lund C, Breen A, Flisher AJ, et al. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:517–28. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Andrade LH, Wang YP, Andreoni S, et al. Mental disorders in megacities: findings from the São Paulo megacity mental health survey, Brazil. PLoS One 2012;7:e31879 10.1371/journal.pone.0031879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gronholm PC, Thornicroft G, Laurens KR, et al. Mental health-related stigma and pathways to care for people at risk of psychotic disorders or experiencing first-episode psychosis: a systematic review. Psychol Med 2017;47:1867–79. 10.1017/S0033291717000344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baum FE, Ziersch AM. Social capital. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:320–3. 10.1136/jech.57.5.320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Webber M, Huxley P, Harris T. Social capital and the course of depression: six-month prospective cohort study. J Affect Disord 2011;129:149–57. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fafchamps M, Lund S. Risk-sharing networks in rural Philippines. J Dev Econ 2003;71:261–87. 10.1016/S0304-3878(03)00029-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. WHO. Review of social determinants and the health divide in the WHO European Region: final report. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Graney MJ. Happiness and social participation in aging. J Gerontol 1975;30:701–6. 10.1093/geronj/30.6.701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Diener E, Seligman ME. Very happy people. Psychol Sci 2002;13:81–4. 10.1111/1467-9280.00415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holder MD, Coleman B. The contribution of social relationships to children’s happiness. J Happiness Stud 2009;10:329–49. 10.1007/s10902-007-9083-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med 1976;38:300–14. 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. De Silva MJ, McKenzie K, Harpham T, et al. Social capital and mental illness: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:619–27. 10.1136/jech.2004.029678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fowler JH, Christakis NA. Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study. BMJ 2008;337:a2338 10.1136/bmj.a2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bassett E, Moore S. Social capital and depressive symptoms: the association of psychosocial and network dimensions of social capital with depressive symptoms in Montreal, Canada. Soc Sci Med 2013;86:96–102. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, et al. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:843–57. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fujiwara T, Kawachi I. A prospective study of individual-level social capital and major depression in the United States. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:627–33. 10.1136/jech.2007.064261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosenquist JN, Fowler JH, Christakis NA. Social network determinants of depression. Mol Psychiatry 2011;16:273–81. 10.1038/mp.2010.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gayen K, Raeside R. Social networks, normative influence and health delivery in rural Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:900–14. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Horng L, Dutta NC, Ahmed S, et al. Peer networking to improve knowledge of child health and immunization services among recently relocated Mothers in Slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016;3(suppl_1):625 10.1093/ofid/ofw172.488 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perkins JM, Subramanian SV, Christakis NA. Social networks and health: a systematic review of sociocentric network studies in low- and middle-income countries. Soc Sci Med 2015;125:60–78. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Islam MN, Iqbal KF. Mental Health and Social Support. The Chittagong Univ. J. B. Sci 2008;3:95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hossain MM, Siddique N-E-A, Habib MFB. Status of marital adjustment, life satisfaction and mental health of tribal (santal) and non-tribal peoples in bangladesh: a comparative study. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2017;22:05–12. 10.9790/0837-2204060512 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hankins M. The reliability of the twelve-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) under realistic assumptions. BMC Public Health 2008;8:355 10.1186/1471-2458-8-355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marsden PV. Recent developments in network measurement : Carrington PJ, Scott J, Wasserman S, Models and methods in social network analysis: Cambridge University Press, 2005:8–30. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bonacich P. Power and centrality: a family of measures. American Journal of Sociology 1987;92:1170–82. 10.1086/228631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jackson MO. Social and economic networks: Princeton university press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chakraborty NM, Fry K, Behl R, et al. Simplified asset indices to measure wealth and equity in health programs: a reliability and validity analysis using survey data from 16 countries. Glob Health Sci Pract 2016;4:141–54. 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35. BBS. Household income and expenditure survey. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krabbendam L, van Os J, Jv O. Schizophrenia and urbanicity: a major environmental influence--conditional on genetic risk. Schizophr Bull 2005;31:795–9. 10.1093/schbul/sbi060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pearl J. Causality: Cambridge university press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Economist Intelligence Unit. High university enrolment, low graduate employment analysing the paradox in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. 2014. http://goo.gl/sVKaD9 (cited 12 Jun 2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020180supp001.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)