Abstract

Objectives

Syphilis is a global health concern with an estimated 12 million infections occurring annually. Due to the increasing rates of new syphilis infections being reported in patients infected with HIV, and their higher risk for atypical and severe presentations, periodic screening has been recommended as a routine component of HIV care. We aimed to characterise incident syphilis presentation, serological features and treatment response in a well-defined, HIV-infected population over 11 years.

Methods

Since 2006, as routine practice of both the Southern Alberta Clinic and Calgary STI programmes, syphilis screening has accompanied HIV viral load measures every 4 months. All records of patients who, while in HIV care, either converted from being syphilis seronegative to a confirmed seropositive or were reinfected as evidenced by a fourfold increase in rapid plasma reagin (RPR) after past successful treatment, were reviewed.

Results

We identified 249 incident syphilis infections in 194 different individuals infected with HIV; 72% were initial infections whereas 28% were reinfections. Half (50.8%) of the infections were asymptomatic and identified only by routine screening. Symptomatic syphilis was more common when RPR titres were higher (p=0.03). In patients with recurrent syphilis infection, a trend was noted favouring symptomatic presentation (62%, p=0.07). All 10 patients with central nervous system (CNS) syphilis involvement presented with an RPR titre ≥1:32. Following syphilis infection, a decline of 42 cells/mm3 in CD4 (p=0.004) was found, but no significant changes in viral load occurred. No association was found with the stage of syphilis or symptoms at presentation and antiretroviral therapy use, CD4 count or virological suppression.

Conclusion

Routine screening of our HIV-infected population identified many asymptomatic syphilis infections. The interaction of HIV and syphilis infection appears to be bidirectional with effects noted on both HIV and syphilis clinical and serological markers.

Keywords: epidemiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

All HIV and sexually transmitted infection care in our region is highly centralised and coordinated allowing for detailed analyses of our population.

Routine syphilis serology regardless of risk behaviours or symptomatology was obtained every 4 months in our HIV-infected population, allowing close monitoring of clinical characteristics, bidirectional interactions as well as inclusivity of incident syphilis infections.

The study population, while comprehensive and representing a Canadian perspective, is from a single regional area and may not be representative of populations elsewhere that have different rates of unprotected sexual activity and both prevalent HIV and syphilis infections. In addition, access to care varies between centres and populations and our rates and identification methods may not precisely match others.

This study may underestimate the clinical impact of syphilis in an HIV-infected population as patients not accessing care and individuals infected but lost to follow up or moving out of Alberta were not analysed.

Introduction

Syphilis continues to be a major public health concern globally, with an estimated 12 million new infections annually.1 Individuals infected with HIV are eight times more likely to become infected with syphilis than the general population.2 In 2016, in Alberta Canada, over 25% of all new syphilis infections occurred in men who have sex with men (MSM) coinfected with HIV.3 It has been suggested that the increased use of social media including websites and mobile apps targeted towards meeting sex partners as well as serosorting (finding sex partners with the same HIV serostatus for unprotected sex) may be contributing to the rebound of high-risk sexual activity in this population.2 4 The suppression of HIV viral replication (viral load <1000 copies/mL) using antiretroviral therapy (ART) resulting in minimal risk for sexual transmission of HIV has received legal recognition in Canada.5 As noted in a 2015 Swiss HIV Cohort Study by Kouyos et al there has been an accelerated rate of condomless sex since the recognition of HIV treatment as prevention. The reasons for increased risk behaviour, particularly condomless sex, are believed to be multifactorial, however in turn may be driving an increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs).6

Syphilis in patients infected with HIV can present in atypical or severe forms, such as ulcerative skin lesions, persistent chancres, gummatous disease, ocular disease and neurosyphilis.7–11 One study showed that individuals infected with HIV have multiple chancres and are more likely to experience Jarisch-Herxheimer reactions (22% vs 12%, respectively), and another showed that concomitant genital ulcers were more common in patients with secondary syphilis and HIV.7 8 STIs may increase the risk of HIV acquisition via interruption of mucosal barriers and increased viral shedding.11–13 It has also been suggested that ART may inadvertently increase the incidence of syphilis by altering innate and acquired immune responses that may enhance susceptibility to syphilis infection.14 Due to these increasing rates of syphilis and the higher likelihood of atypical and severe presentation, routine periodic screening (2–4 times annually) of persons infected with HIV has been recommended.4 11 15–17

The aim of this retrospective cohort study was both to characterise syphilis presentation, serological features and treatment response in a large cohort of individuals infected with HIV engaged in HIV care and receiving regular syphilis testing, as well as to examine the effect of incident syphilis on HIV disease markers.

Methods

Study population

The Southern Alberta Clinic (SAC) and Calgary STI Clinic (CSTI) provide exclusive care to individuals infected with HIV living in Southern Alberta, Canada. In a quality assurance project (approved by University of Calgary Bioethics Committee) at both programmes between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2016, routine syphilis serology regardless of risk was ordered every 4 months accompanying HIV viral load testing. The records of all incident syphilis infections occurring in patients infected with HIV were reviewed. Every indeterminate or positive syphilis serology for a SAC patient was discussed with or referred to CSTI at the time of testing.

All individuals with at least one visit between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2016 were studied. Patients were followed until 31 December 2016 or until they moved, died or were lost to follow up. All patients, who while in HIV care, converted from being seronegative for syphilis to a confirmed positive status or were reinfected with syphilis were reviewed through the SAC database and a CSTI chart review.

Diagnosis

The syphilis screening algorithm and confirmatory testing were achieved using indirect serological methods. Initially, screening for syphilis was done with the non-treponemal rapid plasma reagin (RPR); however, in 2008, the screening test was changed to an enzyme immunoassay (EIA), a treponemal test. The RPR continued to be used as a confirmatory test as well as for monitoring response to therapy.15 18 In Calgary, the secondary confirmatory test was either the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test or the line immunoassay (INNO-LIA).19

Recurrent syphilis episodes were identified by a fourfold increase in RPR after a prior documented successful treatment course for syphilis and were evaluated and staged by an STI specialist (RR). Neurosyphilis was documented by a positive CSF-Venereal Disease Research Laboratory on lumbar puncture as well as evaluated by an STI specialist (RR). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use was not extensively used in the community during the study period and any potential role seemed unlikely.

Data collection

Detailed standardised information was collected by one physician (RL), through a comprehensive review of both SAC and CSTI charts and databases. Multiple data sources in these records were accessed including nursing interviews, social work reports, self-administered questionnaires, laboratory reports and physician notes.

From the SAC database, we identified the number of syphilis tests performed yearly at the clinic per patient as well as the interval between tests. Demographic data were collected at the time of HIV diagnosis and incorporated into the SAC database. These data included: gender (ie, male, female, transgendered), self-reported ethnicity (ie, Caucasian, Indigenous, African/Caribbean/Black, Other) and most likely HIV exposure risk (ie, MSM, heterosexual sex (HET), PWID persons who inject drugs (PWID) and other).

The stage of syphilis (ie, primary, secondary, early latent, late latent) and symptomatology at presentation (ie, rash, ulcer/lesion, influenza-like illness, condylomata, lymphadenopathy, neurological (tinnitus/ocular), asymptomatic, other) were collected via review of CSTI charts. All episodes of syphilis were staged by an STI specialist (RR) based on both clinical and laboratory investigations. In the absence of symptoms, the staging of primary versus latent syphilis was based on the timing of rising RPR titres in relation to most recent prior titre. Prior history of comorbid infections including Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis were self-reported at the time of syphilis diagnosis.

The initial RPR was documented at the time of syphilis diagnosis and recorded in CSTI charts. HIV viral load and CD4 counts were measured at the time of syphilis diagnosis and subsequently at the next routine HIV follow-up appointment. HIV viral suppression was defined as a plasma viral load <40 copies/mL. Treatment modalities (ie, benzathine penicillin, doxycycline, penicillin G) and response to therapy were reviewed retrospectively through a comprehensive chart review. All data were anonymised prior to analysis.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or public were involved in the present study. Our findings have been provided to local public health and will be used in broader STI control initiatives.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical factors of patients were compared using Χ² test. Viral load and CD4 counts prior to and following episode of syphilis infection were compared using the linear mixed effect model while accounting for repeated measurement and more than one episode for some patients. Subgroup analyses were performed on neurosyphilis infections and those with recurrent episodes of syphilis. Patients not accessing care and individuals infected but lost to follow up or moving out of Alberta were not analysed. All statistical analysis was performed using R (R Development Core Team, 2005). All charts were created with Microsoft Excel and R.

Results

Demographics

Between 2006 and 2016, there were 20 203 syphilis tests done on a total of 2448 patients who attended at least one regular SAC visit during that time. On average, there were 180 days between each syphilis test per patient. The average number of syphilis screening tests that were done per patient each year over the 11-year period was 2.1. In 2006, the average number of tests per year was 1.3, whereas in 2016 this was 2.8. For high-risk patients (MSM), screening rates were more frequent with the average testing over 11 years being 2.4 tests per year.

Of the 2448 individuals infected with HIV at SAC and CSTI programmes encompassing 15 175 person years of follow-up between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2016, we identified 322 incident syphilis infections, occurring in 267 different patients. There were 73 syphilis episodes in 73 patients that were excluded. Of those excluded: 41 patients, while being tested in Alberta, had moved out of province resulting in incomplete clinical data, and in 32 patients, there was inadequate basic information available for study inclusion. We therefore analysed 249 episodes in 194 individuals.

Of the 249 infections, 178 (72%) were first episode of a syphilis infection, whereas the remaining 71 (28%) were recurrent episodes. The annual incidence rates of syphilis in our HIV-infected population tripled from 2011, 8.08/1000 patient years (95% CI 4.14 to 14.75), to 27.04 per 1000 person years (95% CI 19.45 to 36.76) in 2016.3 Prior history of STIs included: 32% of cases having a self-reported history of N. gonorrhoeae and 24% having had C. trachomatis infection. The characteristics of the 194 individuals included in this analysis are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV+ patients regularly followed at the Southern Alberta Clinic between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2016 comparing patients who were negative for syphilis (syphilis neg) to patients who ever tested positive for syphilis (syphilis pos).

| Syphilis neg | Syphilis pos | P values | |

| N (%) | 2254 (92.1) | 194 (7.9) | |

| Age at HIV diagnosis (years) | |||

| Mean (range) | 35 (1–79) | 35 (16–69) | 0.893 |

| <30 | 813 (36.1) | 75 (38.7) | 0.801 |

| 30–39 | 802 (35.6) | 66 (34.0) | |

| 40–49 | 438 (19.4) | 37 (19.1) | |

| ≥50 | 201 (8.9) | 16 (8.3) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1675 (74.3) | 183 (94.3) | <0.001 |

| Female | 572 (25.4) | 11 (5.6) | |

| Transgendered | 7 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Self-reported ethnicity* | |||

| Caucasian | 1259 (56.0) | 140 (72.2) | <0.001 |

| Indigenous | 216 (9.6) | 6 (3.1) | |

| ACB | 536 (23.8) | 24 (12.4) | |

| Other | 243 (10.8) | 24 (12.4) | |

| Most likely HIV exposure category† | |||

| MSM | 915 (40.6) | 145 (74.4) | <0.001 |

| HET | 512 (22.7) | 14 (7.2) | |

| PWID | 731 (32.4) | 30 (15.6) | |

| Other | 96 (4.3) | 5 (2.6) |

*Indigenous people includes Aboriginal, Metis and Inuit; ACB includes African, Caribbean, Black; Other includes IndoAsian, Hispanic, East Asian and other.

†HET, self-reported heterosexual identification; MSM, self-reported men who have sex with men identification; PWID, self-reported intravenous drug use identification; Other HIV risk factor behaviour includes: blood transfusions, haemophiliac, neonatal, postnatal infection, unknown or not reported.

Symptomatology

Asymptomatic syphilis episodes

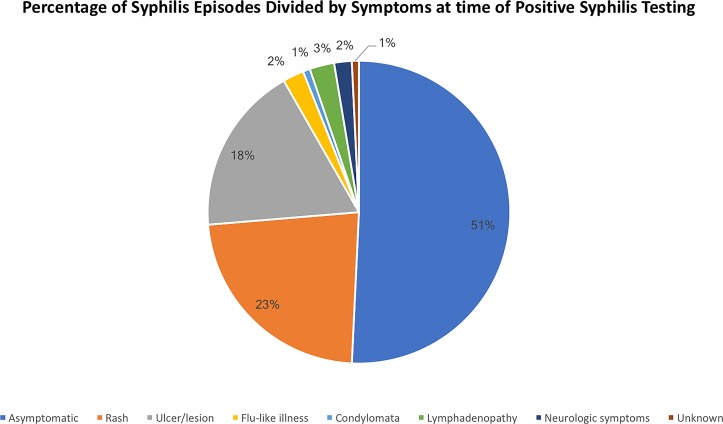

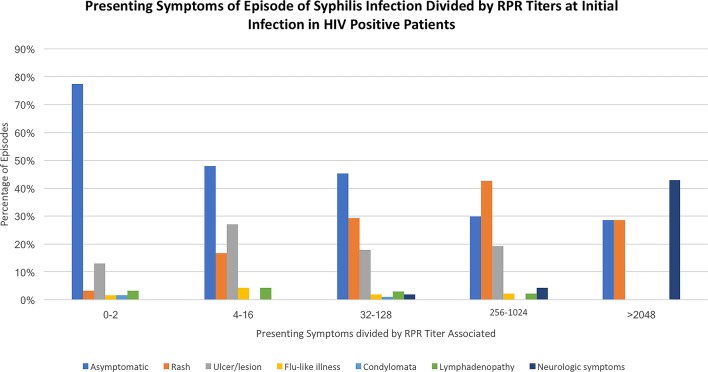

Just over half of the episodes (50.8%) of incident syphilis infections were asymptomatic and identified by routine screening (figure 1). RPR titres were higher in patients with symptomatic versus asymptomatic syphilis (p=0.03) (figure 2). The majority of episodes with an initial RPR of 1:4 or less were asymptomatic (71%). Those with lower CD4 (<200 cells/mm3) counts at syphilis diagnosis had no significant differences in symptomatology as opposed to those with CD4 counts >200 cells/mm3 (p=0.65). Neither virological suppression of HIV nor ART use influenced the individual’s likelihood to present with symptomatic syphilis.

Figure 1.

Percentage of episodes of syphilis diagnosed based on symptoms in a HIV-infected population.

Figure 2.

Percentage of syphilis episodes divided by symptom at presentation based on initial rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titre. Individuals who had symptoms compared with those that did not were more likely to have a higher initial RPR (p=0.0339). The most common symptoms were rash and ulcer/lesion with influenza-like illness, condylomata and lymphadenopathy being relatively rare. Those with neurological symptoms had a significant elevation of their initial RPR titres compared with all other symptoms (p=<0.001) and there were no cases of neurosyphilis with RPR titres less then 1:32 dilutions.

Symptomatic syphilis episodes

The most common presenting symptom was rash (23%), followed by skin lesion or ulceration (18%). Uncommon presentations included lymphadenopathy, influenza-like illness, condylomata lata and neurological symptoms (figure 1). The most common presenting symptom in primary syphilis was skin ulceration/lesion (57%) and in those with secondary syphilis was a rash (76%). However, 15% of those diagnosed with secondary syphilis also complained of skin ulceration or lesion in addition to a rash. Although rare overall as presenting symptoms, lymphadenopathy (86%), influenza-like illness (50%) and condylomata (100%) were most seen in primary syphilis.

Stage of syphilis

Both ART and virological suppression of HIV had no association with the individual’s stage of syphilis at diagnosis. Of those diagnosed with late latent syphilis, 98% had an initial RPR of 1:16 or less. Patients with secondary syphilis tended to present with a higher RPR, 33% having an RPR of 1:256 or higher.

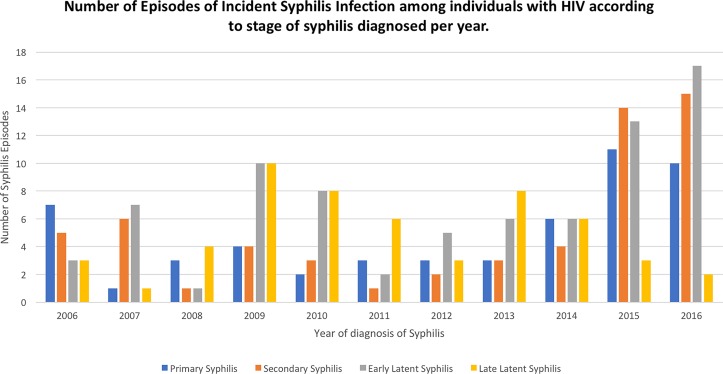

Since 2008, the proportion of late latent syphilis infections diagnosed among our patients infected with HIV in care had decreased from 44% to 4.4% (figure 3). Caucasian individuals were more likely to present with primary (24%) or secondary (28%) syphilis (p=<0.001), whereas the non-Caucasian population were more likely to present with latent disease (74%) (p≤0.001). In men, the majority of infections were early latent (34%) and the minority being late latent (18%). However, in women, 77% of infections were late latent.

Figure 3.

There is an increased number of incident syphilis infections among HIV-positive individuals who are active in care programmes from 2006 to 2016. There is an apparent trend of decreased proportion of late latent disease.

Effect of syphilis on markers of HIV

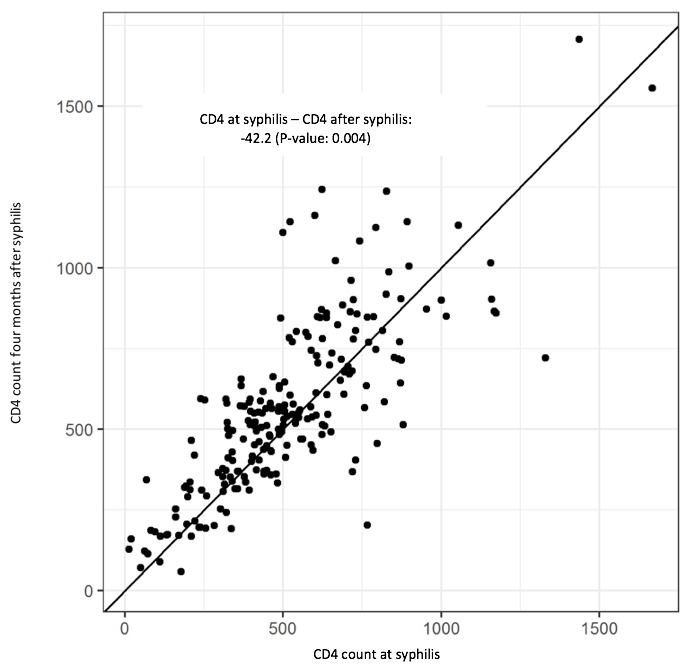

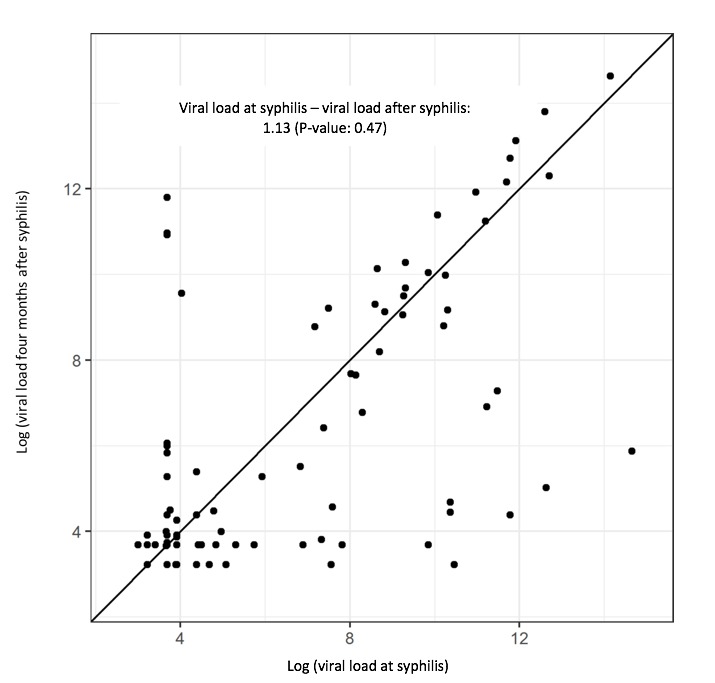

As the interaction of HIV and syphilis infection may be bidirectional, we explored CD4 and viral load response to syphilis infection. A significant decrease in CD4 count of 42.2 cells/mm3 (p=0.004) was noted in association with syphilis coinfection (figure 4). However, there was no change in HIV viral load noted in association with syphilis coinfection (p=0.47) (figure 5).

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of CD4 count at syphilis diagnosis versus CD4 count at follow-up appointment after the treatment of syphilis. CD4 count was noted to decrease by an average of 42.2 cells/mm3 (p=0.004).

Figure 5.

Scatter plot of viral load (adjusted on a logarithmic scale to account for wide variation in values) at syphilis diagnosis versus viral load at follow-up appointment after treatment of syphilis. Viral load was noted to increase by an average of 3.09 copies/mL in relation to syphilis coinfection (p=0.47).

Effect of HIV on markers of syphilis

Nearly half (49%) of all patients presented with RPR (non-treponemal) titres between 1:32 and 1:128. There were two episodes presenting with an initial RPR greater than 1:2048; both patients were not HIV virologically suppressed (HIV plasma viral load >1000 copies/mL) at the time of syphilis infection (figure 2). The individuals viral load (p=0.82) or CD4 count (p=0.48) did not appear to have any correlation with the initial RPR titre. We were unable to evaluate if the absence of ART had an impact on RPR titre due to the small number of patients not on ART (n=48).

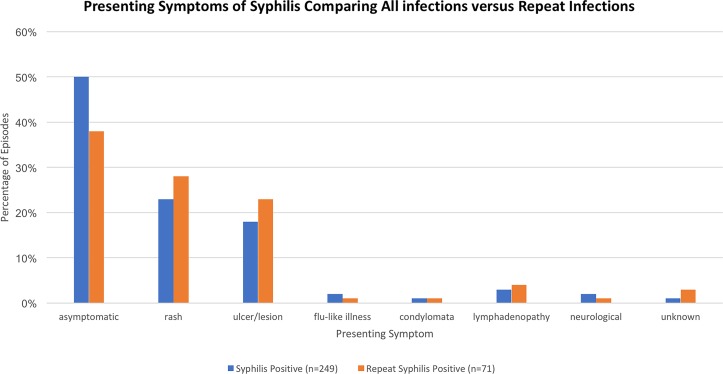

Recurrent episodes of syphilis

In patients with recurrent syphilis infection, a trend (p=0.07) was noted favouring symptomatic presentation (62%). Rash and skin lesion/ulceration also remained the most common complaint (figure 6). Recurrent episodes of syphilis were much less likely to be late latent disease (3%) and instead more likely to be primary (28%), secondary (28%) or early latent disease (39%). Of those with a recurrent syphilis episode, 29% had RPR titres over 1:256, compared with 18% in the study population. Only 10% of the patients with prior syphilis exposure had an initial RPR less than 1:4 compared with 32% in the study population; however, this did not reach significance (p=0.604).

Figure 6.

The percentage of syphilis episodes comparing initial symptom presentation divided by recurrent infections. There is a trend demonstrating that individuals with recurrent syphilis infections were more likely to be symptomatic on presentation; however, this did not reach significance (p=0.0799).

Neurosyphilis

CNS involvement was noted in 10/249 (4%) episodes with a positive CSF-VDRL on lumbar puncture. Ocular symptoms with blurred vision or painless visual loss occurred in four patients, tinnitus in three patients and three were asymptomatic. Nine patients were men and Caucasian with eight being >40 years old. Eight were initial syphilis episodes and two were reinfections. Seven of the 10 patients were on ART, five were virologically suppressed with seven having a CD4 count >500 cells mL. The RPR titre at diagnosis was ≥1:32 in all episodes of CNS involvement with five having an RPR titre of ≥1:512 and two of these episodes diagnosed with initial RPR titres of 1:8192. These RPR titres were much higher than any other symptom presentation (p≤0.001) (figure 2). All patients with CNS involvement were treated successfully, based on both clinical and serological response, with intravenous penicillin G for 14 days.

Treatment

A standard 3-week course of weekly intramuscular injections of benzathine penicillin (2.4 MU/dose) was used for 77% of the patients, while 10% received an oral course of doxycycline, and 10% received a combination of the two medications. Successful completion of the full course of treatment was achieved in 94% (with 5% requiring retreatment from inadequate initial adherence and 1% never completing their full course).

Discussion

Our introduction in 2006 of syphilis screening to accompany routine HIV viral load testing allowed for the identification and analysis of incident syphilis infections in the HIV population in care in Calgary, Alberta. Our results confirm prior findings that coinfection with HIV can result in atypical or severe syphilis presentations.8–11 Compared with non-HIV-infected populations, prior studies have found higher rates of asymptomatic primary syphilis, which may result in missed diagnosis and increased episodes of secondary syphilis.11 20 In our study population, 50.8% (135) syphilis episodes were asymptomatic at presentation, including 21% (10) of the primary syphilis infections. Braun et al recently published a study evaluating symptoms of syphilis in 19 individuals infected with HIV and found the rate of asymptomatic syphilis infections in individuals infected with HIV to be 40%.21 Routine syphilis screening has been confirmed to be effective in detecting early asymptomatic syphilis in outpatients infected with HIV.20

Our study demonstrated a decline in latent syphilis between 2008 (44%) and 2016 (4%). In 2008, the high numbers of latent syphilis may be reflective of a change to the testing algorithm for syphilis, from an initial RPR to EIA, resulting in an improved test sensitivity and the identification of latent syphilis.18 19 While latent episodes have been steadily declining since 2013, the number of primary syphilis diagnoses is increasing. Through regular syphilis screening in this HIV-infected population, earlier detection of syphilis in its primary stage has been achieved, leading to prompt therapy, which may decrease ongoing syphilis transmission.4

The interaction of HIV and syphilis infection appears to be bidirectional with effects noted on both HIV and syphilis serological and clinical markers.11 Prior studies have reported that syphilis infection may increase HIV viral load and decrease CD4 count.7 22–24 We observed a statistically significant decrease in CD4 count associated with incident syphilis infections, but no change in viral load was noted. This difference in findings compared with past studies may in part be explained by the majority of our patients being on ART, which are perhaps more potent in suppressing viral replication.

An increased prevalence of neurological manifestations has been reported in individuals infected with HIV.2 4 Approximately one-third of any patient with early syphilis will have treponemal invasion into their CNS regardless of their HIV status.4 However, an increased rate of early neurosyphilis among individuals infected with HIV has been noted and may be linked to the patient’s inability to control the CNS infection rather than increased invasion into the CNS.4 7 Our data revealed that 10/249 (4%) of the syphilis episodes diagnosed in our HIV-infected cohort were neurosyphilis.

Neurosyphilis is more likely to be asymptomatic in HIV coinfected individuals and therefore a more difficult diagnosis.4 Three of our 10 neurosyphilis episodes were indeed asymptomatic. As a response to the absence of symptoms, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommend individuals infected with HIV who receive a diagnosis of late latent syphilis, unknown duration of disease, have neurological symptoms or treatment failure should undergo CSF evaluation.4 25 It is controversial whether all HIV coinfected individuals require evaluation for neurosyphilis at the time of syphilis diagnosis.4

Recent data suggest that there is an association with RPR titres≥1:32 and laboratory-defined neurosyphilis (sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 40%).7 24 This is in keeping with our study findings, deducing that lumbar puncture could be restricted to the subgroup of patients with neurological manifestation or a serum RPR of ≥1:32.26 27 Prior studies have found that patients with CD4 counts <350 mm3 may be at increased risk for neurosyphilis; however, we identified no specific correlation.4 27 28 We did note that five of the individuals with neurosyphilis were not HIV virologically suppressed, suggesting that there may be a link between increased HIV viral loads and neurosyphilis; however, this requires further study.

The key strength of our study is the detailed longitudinal analysis of clinical, serological and treatment outcomes in our population that is made possible by the highly centralised HIV and STI care programmes in our region. The study population, while comprehensive, is from a single regional area and may not be generalisable to populations elsewhere. Rates of unprotected sexual activity, prevalent HIV and syphilis infections, and access to care vary between centres and populations; therefore, our rates and identification methods may not match others. Limitations of our study include a potential underestimation of the clinical impact of syphilis in this HIV-infected population as patients not accessing care and individuals infected but lost to follow up or who moved from Alberta were not analysed.

Conclusions

Through routine screening of an HIV-infected population engaged in care, many asymptomatic syphilis episodes were identified and treated resulting in a shift in diagnostic stage of syphilis infection from latent to primary and a theoretical decrease in ongoing transmission. Individuals with the symptomatic syphilis infections were more likely to have higher RPR titres and those with highest RPR titres were at greater risk of having neurosyphilis. ART, CD4 count and virological suppression of HIV had no association with the individual’s stage of syphilis or symptoms at diagnosis. Syphilis infection was associated with a temporary decrease in CD4 count with no impact on HIV viral load. As the rates of syphilis rise among the HIV-infected population, ongoing vigilance in screening and treatment is required in addition to further examination of coinfection interactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all clinic staff at SAC and CSTI and especially Janet Furseth and Jennifer Gratrix for their help in the project.

Footnotes

Contributors: RL, RR, HBK and MJG were involved in study design, data extraction, data analysis, drafting and final review of this work. SR, MP and QV were involved in data extraction, data analysis and final review of this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: University of Calgary Bioethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient confidentiality. The sensitive nature of this information as well as the relatively small number of patients included in this dataset may lead it to be identifying and therefore does not allow this dataset to be made public.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections – 2008, 2012. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/stisestimates/en/ (accessed: 6 Dec 2017).

- 2. Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, et al. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. Eur J Intern Med 2009;20:9–13. 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lang R, Read R, Krentz HB, et al. Increasing incidence of syphilis among patients engaged in HIV care in Alberta, Canada: a retrospective clinic-based cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:125 10.1186/s12879-018-3038-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zetola NM, Klausner JD, Syphilis KJD. Syphilis and HIV Infection: An Update. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007;44:1222–8. 10.1086/513427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. v Mabior R. 2012 SCC 47. 2012. https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/10008/index.do

- 6. Kouyos RD, Hasse B, Calmy A, et al. Increases in condomless sex in the swiss hiv cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2015;2:ofv077 10.1093/ofid/ofv077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rolfs RT, Joesoef MR, Hendershot EF, et al. A randomized trial of enhanced therapy for early syphilis in patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. The Syphilis and HIV Study Group. N Engl J Med 1997;337:307–14. 10.1056/NEJM199707313370504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rompalo AM, Joesoef MR, O’Donnell JA, et al. Clinical manifestations of early syphilis by HIV status and gender: results of the syphilis and HIV study. Sex Transm Dis 2001;28:158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marra CM, Tantalo LC, Sahi SK, et al. Reduced Treponema pallidum-Specific Opsonic Antibody Activity in HIV-Infected Patients With Syphilis. J Infect Dis 2016;213:1348–54. 10.1093/infdis/jiv591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Collis TK, Celum CL. The clinical manifestations and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases in human immunodeficiency virus-positive men. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:611–22. 10.1086/318722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lynn WA, Lightman S. Syphilis and HIV: a dangerous combination. Lancet Infect Dis 2004;4:456–66. 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01061-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCoy SI, Eron JJ, Kuruc JD, et al. Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Patients With Acute HIV in North Carolina. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:372–4. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181997252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect 1999;75:3–17. 10.1136/sti.75.1.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rekart ML, Ndifon W, Brunham RC, et al. A double-edged sword: does highly active antiretroviral therapy contribute to syphilis incidence by impairing immunity to Treponema pallidum?. Sex Transm Infect 2017;0:1–5. 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Branger J, van der Meer JTM, van Ketel RJ, et al. High Incidence of Asymptomatic Syphilis in HIV-Infected MSM Justifies Routine Screening. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:84–5. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318186debb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/tg-2015-print.pdf (accessed: 26 Feb 2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17. European AIDS Clinical Society. Guidelines Version 9.0. 2017. http://www.eacsociety.org/files/guidelines_9.0-english.pdf (accessed 26 Feb 2017).

- 18. Ratnam S. The laboratory diagnosis of syphilis. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2005;16:45–51. 10.1155/2005/597580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections: Syphilis 2014. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/std-mts/sti-its/cgsti-ldcits/section-5-10-eng.php (accessed: Dec 6, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cohen CE, Winston A, Asboe D, et al. Increasing detection of asymptomatic syphilis in HIV patients. Sex Transm Infect 2005;81:217–9. 10.1136/sti.2004.012187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Braun DL, Marzel A, Steffens D, et al. High Rates of Subsequent Asymptomatic Sexually Transmitted Infections and Risky Sexual Behavior in Patients Initially Presenting With Primary Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Infection. Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:735-742 10.1093/cid/cix873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buchacz K, Patel P, Taylor M, et al. Syphilis increases HIV viral load and decreases CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected patients with new syphilis infections. AIDS 2004;18:2075–9. 10.1097/00002030-200410210-00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Palacios R, Jiménez-Oñate F, Aguilar M, et al. Impact of syphilis infection on HIV viral load and CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;44:356–9. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802ea4c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sadiq ST, McSorley J, Copas AJ, et al. The effects of early syphilis on CD4 counts and HIV-1 RNA viral loads in blood and semen. Sex Transm Infect 2005;81:380–5. 10.1136/sti.2004.012914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Workowski KA, Berman SM. Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59:1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Libois A, De Wit S, Poll B, et al. HIV and syphilis: when to perform a lumbar puncture. Sex Transm Dis 2007;34:141–4. 10.1097/01.olq.0000230481.28936.e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marra CM, Maxwell CL, Smith SL, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in patients with syphilis: association with clinical and laboratory features. J Infect Dis 2004;189:369–76. 10.1086/381227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ghanem KG, Moore RD, Rompalo AM, et al. Neurosyphilis in a clinical cohort of HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 2008;22:1145–51. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830184df [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.