Abstract

Objectives

To develop a screening battery for office-based clinicians that would assist with the prediction of impaired driving performance and the decision as to who should proceed to road testing in a sample of adults with cognitive and/or visual deficits.

Design

A prospective observational study.

Setting

Driving evaluation clinic at a Veterans Administration Medical Center (VAMC) in St. Louis, Missouri.

Participants

77 individuals with diagnoses of cognitive and/ or visual impairment, age 23 to 91 years, referred to an occupational therapy based driving clinic by VAMC providers due to concerns regarding driving safety.

Measurements

Predictor variables included tests of visual and cognitive functioning, as well as activities of daily living (ADL). The major outcome was pass or fail on a standardized on-road driving test using a performance based road test.

Results

Thirty percent of the referrals failed the road test. The best predictors of driving performance were the Trail Making Test Part A and the Mazes Test from the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (NAB).

Conclusion

Measures of visual search, psychomotor speed, and executive functioning accurately predicted road test performance in a significant number of participants. These brief tests may assist clinicians in deciding who should proceed with a road test in a driver rehabilitation clinic, or perhaps, to whom it should be recommended to cease driving.

Keywords: Automobile driving, Driving safety, Psychometric testing, Road testing

INTRODUCTION

In 2006 there were estimated to be over 30 million licensed drivers over age 65 years in the United States [1]. There is an increased prevalence of chronic diseases with each ensuing decade. A number of these medical conditions may result in functional impairments that negatively affect driving performance [2]. Medical conditions, which are known to affect driving ability, include neurological disease (e.g. multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s, traumatic brain injury, stroke), conditions or diseases affecting vision (e.g. macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, hemianopsia), psychiatric disorders (e.g. bipolar disorder, anxiety), cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease and musculoskeletal disease, along with medication side effects [3].

The performance-based road test is often viewed as the “gold standard” method of assessing driving fitness. However, road tests are expensive, not usually covered by Medicare or insurance, time consuming, may not be readily available or acceptable to patients, and there are concerns of taking severely impaired drivers into actual traffic situations. In addition, many of the conditions impacting driving safety are progressive; therefore, a driver who performs well on the road test at one point may be unsafe months later requiring re-evaluation. Therefore, office-based tests that predict driving performance that are valid and reliable, as well as brief and easily administered, are sorely needed. Impaired cognitive domains that have been associated with decrements in driving performance include: episodic memory [4], visuospatial skills [5], executive function [6], and tests of selected/divided attention [7]. The majority of studies that have attempted to create cognitive test models in regards to road test prediction have typically approached an 80% correct classification rate when using multiple tests [8]. Currently, there is no test battery that has been universally adopted by consensus for use in the clinician’s (e.g., occupational therapist, physician, neuropsychologist) office or in departments of motor vehicles.

In the current study, we were interested in determining whether we could improve on previous predictive models of driving performance by adopting brief visual and/or cognitive tests that could serve as part of a tiered evaluation approach, be easily administered by clinicians or trained staff and adopted at low cost in any setting. This type of effort could be useful in validating an approach by clinicians to assess older drivers as suggested by the American Medical Association [3]. Thus, the goal of this study was to determine if a brief office-based instrument or set of instruments could accurately predict on-road driving performance in a sample of adults referred to a VAMC driving clinic.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Human Studies Committee at the St. Louis VAMC and the Washington University at St. Louis School of Medicine. Participants were referred for a driving evaluation by various VAMC health professionals/providers. The Jefferson Barracks Division of the St. Louis VAMC provides geriatric health care, spinal cord injury treatment, rehabilitation services, psychiatric treatment, a nursing home care unit and a rehabilitation domiciliary program for homeless veterans. The driver rehabilitation clinic has served the region for 30 years and receives referrals from providers within the VAMC system. Fitness-to-drive referrals are frequently made because of cognitive, motor, or visual impairment due to a number of conditions, including dementia, stroke, multiple sclerosis, amputation or spinal cord injury.

All clients referred for a driving evaluation between October 2007–December 2010, were sent information on the research study by mail, including a copy of the informed consent form and the Authorization for Release of Protected Health Information (PHI) form from the VAMC. Upon arrival for their schedule appointment, clients were asked whether they had received the documents and whether there was interest in participating in the study. All subjects were required to re-review and sign all appropriate forms.

Inclusion criteria included: having a referral for driving evaluation due to cognitive and/or visual impairment; having an active driver’s license; being age 18 years and older; having physician approval of the evaluation after referral from a provider; having the ability to understand/communicate in English the informed consent form and comprehend the purpose and objectives of the study; and having at least completed part of the road test (such that a pass/fail determination was made).

Exclusion criteria included: primary joint or muscle impairments (e.g. spinal cord injury, lower extremity amputation, neuropathy, spinal stenosis, degenerative join disease, lower extremity fracture; n=30); cognitive impairment or fatigue too severe to follow road test instructions by the occupational therapist (OT) administering off-road tests (n=12); road test not able to be performed due to weather/snow conditions (n=1).

Data Collection and Measurements

Based on the entry criteria noted above, 77 participants were included in our final sample. The sample included patients with a variety of diagnoses, including macular degeneration, multiple sclerosis, dementia, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, stroke, brain injury, medication side effects, brain tumor, cardiac disease, and cognitive disorder unspecified.

An occupational therapist (OT) interviewed each participant regarding driving history (e.g.. getting lost in familiar areas, stressed while driving, difficulty using car equipment, tickets, crashes, near misses) and functional abilities (e.g., memory problems, family or doctor concerns, managing medications, finances and meal preparation, bathing and dressing ability and recent falls). Training on the administration of the neuropsychological tests was provided by a clinical psychologist with over 20 years of experience. The lead therapist administered the neuropsychological tests and performed the role of the driving instructor on the road test.

Vision Evaluation

Participants were tested for visual acuity, color identification, road sign recognition, depth perception, lateral and vertical phoria and field of vision using the Titmus 2 Screener, using the Drivers Testing Education slides [9].

Cognitive Evaluation

Tests administered included the Freund Clock Drawing test [10] (a measure of executive function and visuospatial abilities); Trail Making Test Parts A and B [11] (a test of psychomotor speed, visual scanning ability, and, for Part B, executive functioning); the Short Blessed Test [12] (a brief mental status screen); and three tests from the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (NAB) [13, 14], including Driving Scenes (a measure of working memory and visual attention), Map Reading (a test of visuospatial functioning, visual scanning, and attention) and Mazes (a measure of psychomotor speed and executive functioning, including, planning, and impulse control).

Motor

The participant’s upper and lower extremity range of motion and strength and cervical range of motion was screened and rated as within functional limits or impaired. Motor speed was assessed with the Rapid Pace Walk [4] (test of lower limb strength, balance, endurance, range of motion).

Traffic Safety Question

13 traffic safety questions were administered and in part were taken from practice questions provided by the Missouri State Department of Revenue for novice drivers. [15]

Road Test

The lead OT performing the driving evaluations was a Certified Driver Rehabilitation Specialist (CDRS) with 9 years of experience performing driving evaluations. The Jefferson Barracks VA Road test (JBVART) was modeled after the modified Washington University Road test [16] and was used for the major outcome measure. The JBVART adapted a qualitative scoring system (e.g. pass, marginal, fail), but did not have the quantitative or point score that would have required a 2nd evaluator in the back seat. Driving initially takes place on the medical center grounds, allowing the participant to become familiar with the car and the surroundings. If the participant is able to demonstrate proficiency with the basic operations of the automobile and follow instructions, they proceed off grounds in a suburban setting.. The course was graduated towards increasing difficulty, with more challenging tasks in the latter aspects of the route (e.g. complex intersections and highway driving).

The road test had 3 unprotected left hand turns, 10 protected left hand turns, 9 unprotected right hand turns, 5 protected right hand turns, and four merges using signs. The unprotected left hand turns were included since difficulty with this specific driving task is over-represented in older adult crashes [17]. The creation of the road test in part was assisted by the initial investigator of the WURT [18]. The JBVART consists of a closed course using hospital grounds so that the participant may become familiar with the vehicle. If the participant was able to demonstrate the ability to operate the vehicle in a safe manner then they proceeded to the open course. The open course moves through a residential area starting with low traffic and then to more complicated driving including a section of interstate. The JBVART is 14 miles long and takes approximately 45 minutes to complete.

All participants drove the facility vehicle with automatic transmission and an instructor’s brake with the OT/CDRS sitting in the passenger's seat evaluating driving performance and safety. At the end of the drive an overall score of pass, marginal or fail was provided by the OT/CDRS. A "fail" rating on the road test was the outcome measure of this study. Marginal and Pass categories were combined. Significant driving errors that resulted in a fail rating were documented a priori and included: if the evaluator had to use the instructors brake or take the wheel to avoid a collision or avoid a dangerous situation; if the driver failed to stop at a stop sign or traffic light, required multiple verbal cues in order to maintain safety; lane drifting; driving in the wrong lane; failure to yield to a pedestrian/vehicle requiring intervention; or if the driver consistently had errors in key driving maneuvers (e.g. scanning, gap acceptance).

Since the lack of blinding to psychometric testing could potentially impact final road test ratings, a second OT and Driver Rehabilitation Specialist (DRS) with 5 years of experience was recruited to review documentation from the original road test and rate performance. This second rater was blind to the neuropsychological and vision testing, as well as the categorical rating (i.e., pass, marginal, fail) of the driving evaluation. The kappa value comparing instructor ratings was good (κ=.62), indicating adequate overall agreement and the lack of impact of the primary rater conducting both the neuropsychological testing and the road test. Therefore, we used the original instructor’s road test evaluation (e.g. pass/fail) as the major driving outcome measure in this study.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V 19.2 [19] and SAS 9.2 [20]. Demographic variables and participant characteristics were evaluated for association to driver JBVART failure by t-test for continuous variables and by Pearson Chi-square test for categorical variables (Table 1). Associations between psychometric tests were examined using Pearson correlation coefficients (data not shown). Individual Receiver Operator Curves (ROC) curves were created with the brief clinician predictor measures and Area Under the Curve (AUC) calculated. Based on these results, stepwise logistic regression was performed to determine which test or combination of tests best were most predictive of a fail rating on our road test.

Table I.

Demographic Characteristics and Measures Based on Road Test Outcome

| Characteristic or Measure |

Total Sample (N=77) Avg+SD |

Pass Road Test (N=49) (64%) |

Fail Road Test (N=28) (36%) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) |

67.8±18.4 (23–91) |

63.5±20.8 (23–89) |

75.4±9.6 (25–91) |

0.006 |

| Gender (% M) |

96% | 94% | 100% | 0.25 |

| Education (years) |

13.0±2.7 (8–20) |

13.4±2.8 (8–20) |

12.4±2.4 (8–17) |

0.13 |

| Race (% AA) |

10% | 8% | 14% | 0.41 |

| Visual Acuity Far OU (≤20/40) |

(N=66) 86% |

(N=46) 94% |

(N=20) 71% |

.02 |

| Field of Vision Right (≥85 degrees) |

(N=61) 80% |

(N=44) 90% |

(N=17) 60% |

.10 |

| Field of Vision Left (≥85 degrees) |

(N=57) 74% |

(N=40) 93% |

(N=17) 60% |

.25 |

|

Short Blessed Test (SBT) (0–28), N=77 |

4.0±5.2 (0–25) |

2.6±2.9 (0–12) |

6.5±7.2 (0–25) |

0.002 |

|

CDT-Freund (0–7), (N=77) |

4.8±1.9 (0–7) |

5.1+1.8 (1–7) |

4.3+1.9 (0–7) |

0.036 |

|

Trails A (secs), N=77 |

62.6±30.8 (18–168) |

47.9±18.0 (18–99) |

88.4±31.6 (46–168) |

<.001 |

|

Trails B (secs), N=77 |

183.3±88.3 (50–304) |

144.8±72.8 (50–301) |

250.6±71.5 (102–301) |

<.001 |

|

Maze Test N=72 |

6.3±5.6 (0–22) |

8.0±5.6 (1–22) |

2.6±3.2 (0–12) |

<.001 |

|

Driving Scenes N=77 |

37.0±9.9 (4–61) |

40.6±8.3 (23–61) |

30.7±9.3 (4–51) |

<.001 |

|

Map Reading N=72 |

6.4±2.2 (0–11) |

7.0±2.0 (3–11) |

5.2±2.0 (0–9) |

<.001 |

Abbreviations: M, Male; AA, African American; OU, Both Eyes; CDT, Clock Drawing Test

RESULTS

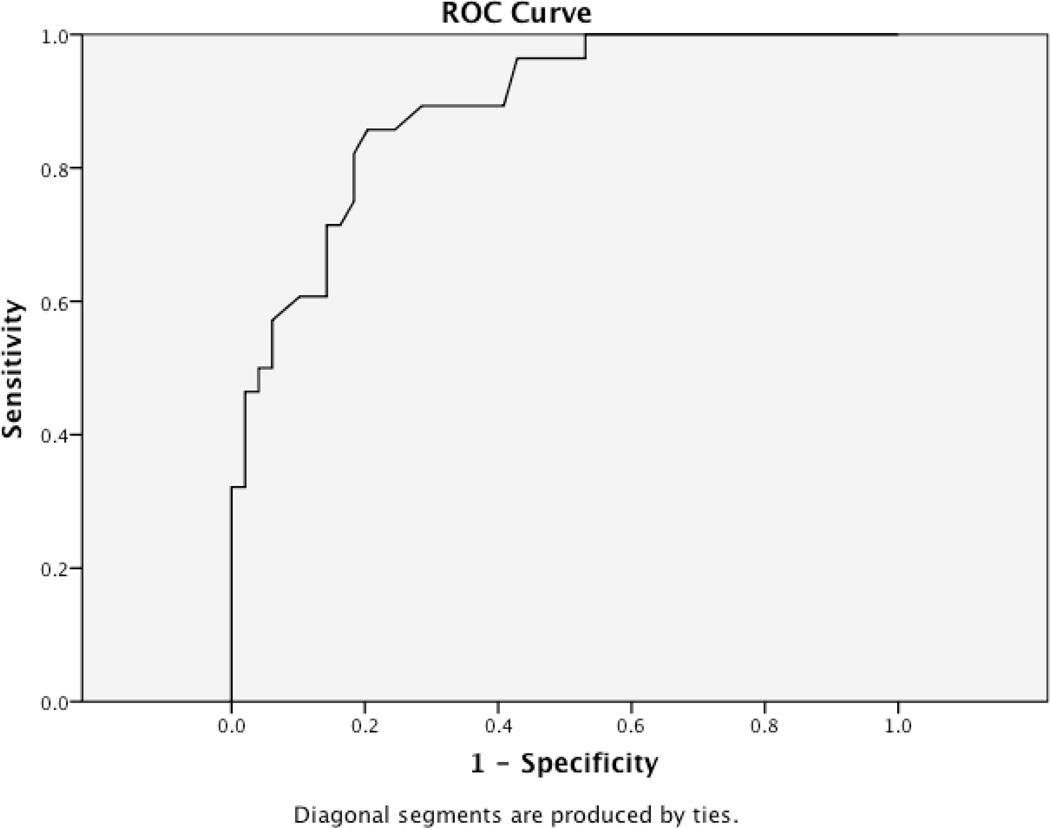

Table 1 reveals the demographic information and tests of functional abilities based on road test outcome. Table 2 presents individual test characteristics for those psychometric tests that had good to excellent prediction of road test performance (e.g. AUC's >.85). Using a simple logistic regression approach, the two tests that were most accurate in predicting failure on our road test included two individual tests: Trail Making Test Part A and the Maze Test from the NAB. Figure 1 depicts the ROC curve for Trails A. Trying to combine both of these tests or other tests did not enhance the predictive value of the individual tests. When Trail Making B Test was added to Trail Making A test, the addition was marginally statistically significant (p=.053, CI 1.01–1.02). However, Trail Making Test B was difficult to perform for this group of patients and 25% of the sample could not complete the test in under 5 minutes, making it less useful for a screening test.

Table II.

Specific Test Characteristics of Selected Psychometric Tests in Predicting Failure on the Road Test

| Test Cut Point | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value |

Negative Predictive Value |

LR+ | LR− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Trailmaking Test A* (N=77, AUC=.89) 40 seconds |

1.000 | .367 | .475 | 1.000 | 4.5 | .22 |

|

Trailmaking Test A 60 seconds |

.821 | .816 | .719 | .8889 | 4.5 | .22 |

|

Trailmaking Test A 80 seconds |

.500 | .939 | .8324 | .767 | 8.2 | .53 |

|

Mazes+ (N=72, AUC=.85) Range 0–22 17 |

.786 | .102 | .333 | .455 | .875 | 2.100 |

|

Mazes 5.5 |

.679 | .571 | .475 | .757 | 1.583 | .563 |

|

Mazes .5 |

.107 | 1.000 | 1.000 | .662 | 0 | .893 |

Higher scores for Trailmaking Test Part A indicates poorer performance

Lower scores on Mazes indicate poorer performance

Figure I.

ROC CURVE for Trailmaking Test A

DISCUSSION

Almost 1/3 of the driver’s referred to the VA driving clinic failed our road test. This is higher than previously reported studies [21,22]. However, many published studies examining road test performance in medically impaired older adults recruited samples in a research setting where one might anticipate a higher level of driving skills due to volunteer bias. This study examined patients that were deemed “at-risk” due to presence of medical illnesses and concerns raised by health professionals and/or families. This higher rate could also be explained by additional factors such as issues related to course difficulty, instructor bias or other factors not related to disease severity but simply not assessed during the driving evaluation (e.g. fatigue from off-road and on-road testing, test anxiety, lifelong poor driving habits, personality characteristics, etc.).

The office-based tests which best-predicted failure on the road test were the Trail Making Test Part A and the Mazes Test from the NAB. Recent papers have found that similar tests of visuospatial skill (including visual search), psychomotor speed, executive functioning, and attention have predicted on-road driving performance [7, 8, 14]. Individual tests or combinations have been shown in the literature to have usefulness in some samples that have included medically impaired older drivers [22, 23, 24]. In our study, the AUC for the two tests were so high, that adding additional tests did not add to the predictive power of the individual tests. Although each individual test in our sample had acceptable sensitivity and specificity, as well as overall accuracy rates consistent with those in previous studies, cut-offs should probably be set to minimize the number of false positives (e.g. those that are safe to drive who test positive and should not be penalized). This will continue to be a matter of public debate among clinicians and policy makers.

Trail Making A is available in the public domain, is brief (~ under one minute to administer) and can be scored easily and quickly. However, it was recently noted to have less acceptability than other cognitive tests as reported by our patients referred for driving evaluations [25]. Presumably, patients may have difficulty understanding the relevance of the test to driving. The Mazes test from the NAB requires purchase, additional training, and time for administration (~5–10 minutes), but may be more acceptable or face valid as a measure of or proxy for driving impairment for clientele in this setting.

There are several limitations to this study. Our road test has not yet been validated with retrospective or prospective crash data. Our medically impaired sample was heterogeneous, mostly male, and was recruited in a VA setting making generalizability limited. There are other factors which could influence road test results which were not measures in this study and include but are not limited to; personality characteristics, lifelong driving habits, depression, etc. All of these areas and others such as lack of confidence [25] and test anxiety [26] may need to be quantified during future studies on prediction of driving outcomes, to determine whether there are differences on road test performance and whether their testing would improve prediction of our models.

This study lacks validation with model testing data. Validation will need to await larger data sets from a variety of sites to determine whether these tests should be adopted to assist in making driving decisions prior to road testing. It should be noted that we excluded those veterans referred to our driving clinic with motor deficits. Thus, these findings should not be generalized to this subset of patients. However, our findings are consistent with other tests that were found to be predictive in the literature [8, 27]. Historically been a poor match between traditional psychometric tests and road test performance [28]. Future research will need to focus on those components of driving behavior to develop new and/or novel tests that will improve predictive power [29]

In summary, brief office tests of visual scanning and processing speed (e.g. Trail Making Test Part A or the NAB Maze Test) were able to correctly classify a high percentage of drivers into a pass/fail category. Just as important, these tests are brief, administered in less than 10 minutes, and could be adopted in a clinical setting with appropriate training of personnel to administer psychometric tests. Further studies are needed to determine the ability of these tests to assist in determining who should be referred for on-road testing. Additional discussion among clinicians and our patients and/or caregivers are needed to determine the level of medical uncertainty that is acceptable to create and/or adopt these tools for clinical use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Linda Hunt for her assistance in providing counsel and advice to recreate the modified Washington University Road test.

Conflict of Interest

This material is a result of work supported with the resources and use of facilities at the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Jefferson Barracks Division, St. Louis, MO; Principal investigator, Patricia M. Niewoehner, staff occupational therapist, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Extended Care and Rehabilitation Services.

This study was funded by support from the Missouri Department of Transportation and the Division of Highway Safety and the Longer Life Foundation, the Washington University Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (P50AG05681, Morris PI) and the program project, Healthy Aging and Senile Dementia (P01AG03991, Morris PI),

Dr. Stern is a co-author of the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery and received related royalties. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG13846; RAS) and a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association (IIRG-08-89720; RAS). For information about the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery, contact; Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. www.parinc.com

David B. Carr: NIA grants and the Missouri Department of Transportation/ Highway Safety grant Speaker Forum: Alzheimer’s Association; Consultant ADEPT and Pfizer

Pat Niewoehner:

Rochelle Henderson:

Jami Dalchow:

Tracy Beardsley:

Robert Stern: Grants/funds: NIH; Jannsen; Pfizer; Speaker Forum: Lilly, Jannsen Alz Immunoth, Neuronix; Royalties: PAR Inc

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of paper.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

David Carr: Designing the study, methodology, interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript.

Pat Niewoehner: Study design, collection and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript.

Rochelle Henderson: Interpretation of data, statistical analysis, and preparation of manuscript.

Jami Dalchow : Study design, interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript

Tracy Beardsley: Interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript

Robert Stern: Interpretation of data, manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.NHTSA, Traffic Safety Facts 2007 data: Older population. Washington, DC: 2008. p. No. DOT HS 810 992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobbs BM. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2005. Medical Conditions and Driving: A Review of the Literature (1960–2000) Report # DOT HS 809 690. www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/researchMedical_Condition_Driving/pages/TRD.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr DB, Schwartzberg JG, Manning L, et al. Physicians's Guide to Assessing and counseling Older Drivers. 2nd edition. Washington, D.C.: NHTSA; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staplin L, Gish K, Wagner E. MaryPODS revisited: Updated crash analysis and implications for screening program implementation. J Safety Res. 2003;34:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reger MA, Welsh RK, Watson GS, et al. The relationship between neuropsychological functioning and driving ability in dementia: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychology. 2004;18:85–93. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ott BR, Daiello LA, Lapane KL, et al. How does dementia affect driving in older patients? Aging Health. 2010;6:77–85. doi: 10.2217/ahe.09.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathias J, Lucas L. Cognitive predictors of unsafe driving in older drivers: A meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:637–653. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209009119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carr DB, Ott BR. The older adult driver with cognitive impairment: "It's a very frustrating life". JAMA. 2010;303:632–641. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Titmus2. Vision Tester training manual, drivers education model. Petersburg, VA: Titmus Optical; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freund B, Gravenstein S, Ferris R, et al. Drawing clocks and driving cars. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:240–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reitan R. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, et al. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stern RA, White T. Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (NAB) Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown LB, Stern RA, Cahn-Weiner DA, et al. Driving Scences test of the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (NAB) and on-road driving performance in aging and very mild dementia. Arch of Clin Neuropsychol. 2005;20:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Personal Communication Missouri Department of Revenue. Highway Patrol Divison [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr DB, Barco PB, Wallendorf MJ, et al. Predicting road test performance in drivers with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2112–2117. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preusser DF, Williams AF, Ferguson SA, et al. Fatal crash risk for older drivers at intersections. Accid Anal Prev. 1998;30:151–159. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(97)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt LA, Murphy CF, Carr D, et al. Reliability of the Washington University Road Test. A performance-based assessment for drivers with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:707–712. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550180029008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statistical package for the social sciences. Armonk, New York: IBM; [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cary, North Carolina: SAS Institute, Inc; [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ott BR, Heindel WC, Papandonatos GD, et al. A longitudinal study of drivers with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1171–1180. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000294469.27156.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lincoln NB, Radford KA, Lee E, et al. The assessment of fitness to drive in people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:1044–1051. doi: 10.1002/gps.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobbs BM, Schopflocher D. The Introduction of a New Screening Tool for the Identification of Cognitively Impaired Medically At-Risk Drivers: The SIMARD A Modification of the DemTect. J Prim Care Community Health. 2010;1:119–127. doi: 10.1177/2150131910369156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dawson JD, Anderson SW, Uc EY, et al. Predictors of driving safety in ealry Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2009;72:521–527. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341931.35870.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalchow JL, Niewoehner PM, Henderson RR, et al. Test acceptability and confidence levels in older adults referred for fitness-to-drive evaluations. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64:252–258. doi: 10.5014/ajot.64.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhalla RK, Papandonatos GD, Stern RA, et al. Anxiety of Alzheimer's disease patients before and after a standardized on-road driving test. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bédard M, Weaver B, Darzins P, et al. Predicting driving performance in older adults: We are not there yet! Traffic Inj Prev. 2008;9:336–341. doi: 10.1080/15389580802117184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ranney T. Models of driving behavior: A review of their evaluation. Accid Anal Prev. 1994;26:735–750. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuller R. Towards a general theory of driver behavior. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37:461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]