Abstract

Background

Hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge (30-d readmission) is an undesirable outcome. Readmission of patients with diabetes is common and costly. Most of the studies that have examined readmission risk factors among diabetes patients did not include potentially important clinical data.

Objectives

To provide a more comprehensive understanding of 30-d readmission risk factors among patients with diabetes based on pre-discharge and post-discharge data.

Research Design

In this retrospective cohort study, 48 variables were evaluated for association with readmission by multivariable logistic regression.

Subjects

17,284 adult diabetes patients with 44,203 hospital discharges from an urban academic medical center between January 1, 2004 and December 1, 2012

Measures

The outcome was all-cause 30-d readmission. Model performance was assessed by C statistic.

Results

The 30-d readmission rate was 20.4%, and the median time to readmission was 11 days. A total of 27 factors were statistically significantly and independently associated with 30-d readmission (p<0.05). The C statistic was 0.82. The strongest risk factors were lack of a post-discharge outpatient visit within 30 days, hospital length-of-stay, prior discharge within 90 days, discharge against medical advice, sociodemographics, comorbidities, and admission laboratory values. A diagnosis of hypertension, pre-admission sulfonylurea use, admission to an intensive care unit, gender and age were not associated with readmission in univariate analysis.

Conclusions

There are numerous risk factors for 30-d readmission among patients with diabetes. Post-discharge factors add to the predictive accuracy achieved by pre-discharge factors. A better understanding of readmission risk may ultimately lead to lowering that risk.

Keywords: readmissions, diabetes, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Hospital readmission is an undesirable outcome that may be preventable. Recently, increasing attention is being focused on readmission of patients with diabetes. Diabetes affects a substantial proportion of hospitalized patients and is associated with considerable costs. Patients with diagnosed diabetes account for more than 8 million discharges/year in the US, approximately 25% of all discharges.1 In 2012, total US hospital cost attributable to diabetes patients was $124 billion, with 30-day (30-d) readmissions contributing at least $20 billion.2,3 The best estimates of 30-d readmission rates among those with diabetes are 16.0 to 20.4%,4–8 and readmission is 17% more likely among patients with diabetes compared to those without.5

A thorough understanding of readmission risk factors is needed to identify high risk individuals and reduce readmission rates. Most of the studies that have examined readmission risk factors among diabetes patients did not include potentially important clinical data such as laboratory values and medication use history.3–7,9,10 In a prior study that did examine such factors, the development and validation of the Diabetes Early Readmission Risk Indicator (DERRI) was presented.8 Because the DERRI was designed as a predictive tool for use at the point-of-care in hospitalized patients before discharge, neither post-discharge information nor a comorbidity index were included. Furthermore, the number of predictors retained in the model was limited to maximize ease-of-use. Lastly, the study sample was split into development and validation datasets. To provide a more comprehensive understanding of 30-d readmission risk factors based on pre-discharge and post-discharge data, the entire DERRI sample of hospitalized patients with diabetes was analyzed for associations of sociodemographic, clinical and administrative variables with readmission.

In addition to the variables previously evaluated in the DERRI development study, the following 4 variables were examined based on published data suggesting association with readmission among diabetes patients: having a follow up appointment within 30 days of discharge, hospital length of stay (LOS), Charlson comorbidity index,11 and discharge status from the index hospitalization.3 Lastly, year of index discharge was included in the model to adjust for potential changes in readmission rates during the study period.

METHODS

Study Sample

In this retrospective cohort study, electronic medical records of 17,284 patients with 44,203 hospital discharges between January 1, 2004 and December 1, 2012 from an urban academic medical center (Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA) were analyzed. Boston Medical Center is the largest safety net hospital and busiest emergency services center in New England, with approximately 500 beds. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of diabetes defined by an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code of 250.xx associated with hospital discharge or the presence of a diabetes-specific medication on the preadmission medication list. Exclusion criteria were patients younger than 18 years on the day of an index admission, discharge by transfer to another hospital, discharge from an obstetric service, inpatient death, outpatient death within 30 days of discharge, missing data or lacking 30 days of follow up after discharge. Readmission that occurred within 8 hours after an index discharge was considered false positive and merged with the discharge to avoid counting in-hospital transfer as a readmission. During the study period, patients received usual care. There was no systematic diabetes-focused intervention for discharge procedures other than inpatient consultation of the diabetes management team as requested by the primary hospital providers. The Boston Medical Center and Temple University Institutional Review Boards approved the protocol.

Definition of Variables

A total of 48 variables were evaluated for association with all-cause hospital readmission within 30 days of index discharge (Supplemental Table). This included variables previously evaluated to develop a predictive model of readmission.8 Additionally, the following 4 variables were examined based on literature review: having a follow up appointment within 30 days of discharge, hospital length of stay (LOS), Charlson comorbidity index,11 and discharge status from the index hospitalization.3 This version of the Charlson index is a measure of comorbidity burden associated with inpatient death based on a set of 17 specific conditions that does not include any of the conditions used as covariates in the present study. Because the Charlson index includes chronic lung disease, malignant neoplasm, and the macrovascular complications of diabetes, these 3 factors were not included in the multivariable analysis. Lastly, year of index discharge was included in the model to adjust for potential changes in readmission rates during the study period. Variables based on ICD-9-CM codes were defined as previously reported.8 Data were collected during the course of routine clinical care in the electronic medical record.

Variables were based on information at the time of the index admission. In general, the first laboratory values available during the 24 hours before the time of admission were used. The serum albumin level closest to the time of admission was used, up to 30 days before or during the admission. Most extreme blood glucose level was based on capillary point-of-care or venous values during the entire hospitalization.

Statistical Analysis

Summaries of categorical variables included counts and percentages, while means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were used for continuous variables. Readmitted patients were compared to non-readmitted patients by chi-square tests for categorical variables and 2-sample t-tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. Non-normally distributed continuous variables, i.e., admission serum creatinine and LOS, were log transformed for modeling procedures.

Univariate analyses were performed for all variables to determine those associated with 30-d readmission. Variables associated with readmission at the P <0.1 level in univariate analyses were selected for multivariable modelling. Multivariable logistic regression with generalized estimating equations (GEE) and best subset selection was performed to determine the adjusted associations of the variables with all-cause 30-d readmission.12,13 The GEE method accounts for clustering of repeated observations, in this case, multiple discharges per patient. Variables independently associated with 30-d readmission at the P <0.05 level were retained in the multivariable model. Model performance was evaluated by the C statistic to represent the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, for which higher values represent better discrimination.14 All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 9034 (20.4%) discharges out of the 44203 index discharges in the study were associated with 30-d readmission for any cause. The study cohort is well-distributed across age and sex (Table 1). A majority of the discharges were among patients who were unmarried, educated at a high-school level or less, disabled, retired, or unemployed, insured by Medicare or Medicaid, overweight or obese, and lived within 5 miles of the hospital. This is an ethnically diverse sample, with 45.5% of discharges identified as black, 15.5% as Hispanic, and 32.8% as white. Pre-admission diabetes therapy included sulfonylureas for 15.2%, metformin for 28.1%, insulin therapy for 37.5% of all discharges. No microvascular complications were present in nearly 70% of discharges. In contrast, a majority discharges were of patients with at least 1 macrovascular complication. Other common comorbidities were depression, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma, cardiac dysrhythmias, and anemia. The median LOS was 3.6 days.

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospitalized patients with diabetes by 30-d readmission status

| Variable | All discharges N=44203 |

Followed by readmission N=9034 |

No readmission N=35169 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Variables | ||||

| Hospital | ||||

| Length-of-stay (days), median (IQR) | 3.6 (2.1, 6.3) | 3.5 (2.1, 6.1) | 4.0 (2.5, 7.1) | <0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 2054 (4.7) | 317 (3.5) | 1737 (4.9) | |

| 1-2 | 12459 (28.2) | 1840 (20.4) | 10619 (30.2) | |

| 3-4 | 10177 (23.0) | 1876 (20.8) | 8301 (23.6) | |

| 5-6 | 4839 (11.0) | 1186 (13.1) | 3653 (10.4) | |

| >6 | 14674 (33.2) | 3815 (42.2) | 10859 (30.9) | |

| Post-discharge | ||||

| Outpatient visit | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 20044 (45.4) | 2886 (32.0) | 17158 (48.8) | |

| No | 12939 (29.3) | 5680 (62.9) | 7259 (20.6) | |

| Not documented | 11220 (25.4) | 468 (5.2) | 10752 (30.6) | |

| Year of discharge | <0.001 | |||

| 2004 | 4198 (9.5) | 822 (9.1) | 3376 (9.6) | |

| 2005 | 4253 (9.6) | 791 (8.8) | 3462 (9.8) | |

| 2006 | 4433 (10.0) | 848 (9.4) | 3585 (10.2) | |

| 2007 | 5215 (11.8) | 1016 (11.3) | 4199 (11.9) | |

| 2008 | 5461 (12.4) | 1076 (11.9) | 4385 (12.5) | |

| 2009 | 5851 (13.2) | 1161 (12.9) | 4690 (13.3) | |

| 2010 | 5774 (13.1) | 1167 (12.9) | 4607 (13.1) | |

| 2011 | 5057 (11.4) | 1241 (13.7) | 3816 (10.9) | |

| 2012 | 3961 (9.0) | 912 (10.1) | 3049 (8.7) | |

| Discharge status of index admission | <0.001 | |||

| Home | 25740 (58.2) | 4719 (52.2) | 21021 (59.8) | |

| Home with nursing care | 8456 (19.1) | 1939 (21.5) | 6517 (18.5) | |

| Sub-acute facility | 8790 (19.9) | 2023 (22.4) | 6767 (19.2) | |

| Against medical advice | 924 (2.1) | 302 (3.3) | 622 (1.8) | |

| Other | 293 (0.7) | 51 (0.6) | 242 (0.7) | |

| Previously studied variables | ||||

| Sociodemographic/Administrative | ||||

| Age | 0.12 | |||

| <50 years | 8455 (19.1) | 1826 (20.2) | 6629 (18.9) | |

| 50 – 59 years | 10216 (23.1) | 2129 (23.6) | 8087 (23.0) | |

| 60 – 69 years | 11466 (25.9) | 2352 (26.0) | 9114 (25.9) | |

| 70+ years | 14066 (31.8) | 2727 (30.2) | 11339 (32.2) | |

| Gender | 0.083 | |||

| Female | 22286 (50.4) | 4421 (48.9) | 17865 (50.8) | |

| Male | 21917 (49.6) | 4613 (51.1) | 17304 (49.2) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| Black | 20126 (45.5) | 4598 (50.9) | 15528 (44.2) | |

| Hispanic | 6856 (15.5) | 1403 (15.5) | 5453 (15.5) | |

| White | 14504 (32.8) | 2638 (29.2) | 11866 (33.7) | |

| Other or not documented | 2717 (6.2) | 395 (4.4) | 2322 (6.6) | |

| English speaking | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 35858 (81.1) | 7500 (83.0) | 28358 (80.6) | |

| No | 8345 (18.9) | 1534 (17.0) | 6811 (19.4) | |

| Education level | <0.001 | |||

| Less than high school | 6058 (13.7) | 1311 (14.5) | 4747 (13.5) | |

| Any high school | 24243 (54.8) | 5499 (60.9) | 18744 (53.3) | |

| Some college | 2976 (6.7) | 602 (6.7) | 2374 (6.8) | |

| College graduate | 6724 (15.2) | 1125 (12.5) | 5599 (15.9) | |

| Not documented | 4202 (9.5) | 497 (5.5) | 3705 (10.5) | |

| Employment | <0.001 | |||

| Disabled | 9505 (21.5) | 2709 (30.0) | 6796 (19.3) | |

| Employed | 4317 (9.8) | 458 (5.1) | 3859 (11.0) | |

| Retired | 16985 (38.4) | 3496 (38.7) | 13489 (38.4) | |

| Unemployed | 12046 (27.3) | 2254 (25.0) | 9792 (27.8) | |

| Other or not documented | 1350 (3.1) | 117 (1.3) | 1233 (3.5) | |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Medicaid | 9747 (22.1) | 2342 (25.9) | 7405 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Medicare | 22118 (50.0) | 4758 (52.7) | 17360 (49.4) | |

| None | 2297 (5.2) | 259 (2.9) | 2038 (5.8) | |

| Private | 10041 (22.7) | 1675 (18.5) | 8366 (23.8) | |

| Home zip code | <0.001 | |||

| ≥8 km from hospital | 13738 (31.1) | 2169 (24.0) | 11569 (32.9) | |

| <8 km from hospital | 30465 (68.9) | 6865 (76.0) | 23600 (67.1) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 13780 (31.2) | 2592 (28.7) | 11188 (31.8) | |

| Single | 29526 (66.8) | 6329 (70.1) | 23197 (66) | |

| Other or not documented | 897 (2.0) | 113 (1.3) | 784 (2.2) | |

| Pre-admission clinical | ||||

| Pre-admission sulfonylurea use | 0.44 | |||

| Yes | 6697 (15.2) | 1403 (15.5) | 5294 (15.1) | |

| No | 37506 (84.9) | 7631 (84.5) | 29875 (85.0) | |

| Pre-admission metformin use | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 12400 (28.1) | 2054 (22.7) | 10346 (29.4) | |

| No | 31803 (72.0) | 6980 (77.3) | 24823 (70.6) | |

| Pre-admission thiazolidinedione use | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 3008 (6.8) | 466 (5.2) | 2542 (7.2) | |

| No | 41195 (93.2) | 8568 (94.8) | 32627 (92.8) | |

| Pre-admission insulin use | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 16555 (37.5) | 4388 (48.6) | 12167 (34.6) | |

| No | 27648 (62.6) | 4646 (51.4) | 23002 (65.4) | |

| Pre-admission glucocorticoid use | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 4320 (9.8) | 1215 (13.5) | 3105 (8.8) | |

| No | 39883 (90.2) | 7819 (86.5) | 32064 (91.2) | |

| Pre-admission blood pressure meds | <0.001 | |||

| None | 12274 (27.8) | 1903 (21.1) | 10371 (29.5) | |

| ACE-i or ARB | 21352 (48.3) | 4639 (51.4) | 16713 (47.5) | |

| Non-ACE or ARB | 10577 (23.9) | 2492 (27.6) | 8085 (23.0) | |

| Pre-admission statin use | 0.0066 | |||

| Yes | 21153 (47.9) | 4507 (49.9) | 16646 (47.3) | |

| No | 23050 (52.2) | 4527 (50.1) | 18523 (52.7) | |

| Discharged 90 days prior to index admission | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 14168 (32.1) | 4740 (52.5) | 9428 (26.8) | |

| No | 30035 (68.0) | 4294 (47.5) | 25741 (73.2) | |

| Discharge status 1 year prior to index admission | <0.001 | |||

| Home | 15798 (35.7) | 3904 (43.2) | 11894 (33.8) | |

| Home with nursing care | 5792 (13.1) | 1583 (17.5) | 4209 (12.0) | |

| Sub-acute facility | 5320 (12.0) | 1448 (16.0) | 3872 (11.0) | |

| Against medical advice | 666 (1.5) | 238 (2.6) | 428 (1.2) | |

| No discharge recorded | 16627 (37.6) | 1861 (20.6) | 14766 (42.0) | |

| Hospital | ||||

| Body mass index | 0.0018 | |||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 1038 (2.4) | 265 (2.9) | 773 (2.2) | |

| 18.5 – 24.9 kg/m2 | 7412 (16.8) | 1663 (18.4) | 5749 (16.4) | |

| 25.0 – 29.9 kg/m2 | 12377 (28) | 2480 (27.5) | 9897 (28.1) | |

| ≥30.0 kg/m2 | 23376 (52.9) | 4626 (51.2) | 18750 (53.3) | |

| Blood transfusion given | 0.022 | |||

| Yes | 6052 (13.7) | 1468 (16.3) | 4584 (13.0) | |

| No | 38151 (86.3) | 7566 (83.8) | 30585 (87.0) | |

| Parenteral or enteral nutrition | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1592 (3.6) | 434 (4.8) | 1158 (3.3) | |

| No | 42611 (96.4) | 8600 (95.2) | 34011 (96.7) | |

| Diabetes inpatient consultation | 0.0055 | |||

| Yes | 5697 (12.9) | 1072 (11.9) | 4625 (13.2) | |

| No | 38506 (87.1) | 7962 (88.1) | 30544 (86.9) | |

| Current infection,a | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 9975 (22.6) | 2206 (24.4) | 7769 (22.1) | |

| No | 34228 (77.4) | 6828 (75.6) | 27400 (77.9) | |

| Current complication of device, graft, or implant | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1820 (4.1) | 506 (5.6) | 1314 (3.7) | |

| No | 42383 (95.9) | 8528 (94.4) | 33855 (96.3) | |

| Current fluid or electrolyte disorder | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 8913 (20.2) | 2265 (25.1) | 6648 (18.9) | |

| No | 35290 (79.8) | 6769 (74.9) | 28521 (81.1) | |

| White blood cell count | <0.001 | |||

| Low <4.0 × 109 L | 2019 (4.6) | 594 (6.6) | 1425 (4.1) | |

| Normal 4.0 – 11.0 × 109 L | 33932 (76.8) | 6694 (74.1) | 27238 (77.5) | |

| High >11.0 × 109 L | 8252 (18.7) | 1746 (19.3) | 6506 (18.5) | |

| Hematocrit (%), mean (SD) | 33.7 (5.29) | 34.0 (5.27) | 32.4 (5.14) | <0.001 |

| Serum albumin | <0.001 | |||

| 40+ g/L | 15049 (34.1) | 2627 (29.1) | 12422 (35.3) | |

| <40 g/L | 23586 (53.4) | 5558 (61.5) | 18028 (51.3) | |

| Not documented | 5568 (12.6) | 849 (9.4) | 4719 (13.4) | |

| Serum sodium | <0.001 | |||

| Low <135 mmol/L | 4743 (10.7) | 1257 (13.9) | 3486 (9.9) | |

| Normal 135 – 145 mmol/L | 39026 (88.3) | 7680 (85) | 31346 (89.1) | |

| High >145 mmol/L | 434 (1) | 97 (1.1) | 337 (1.1) | |

| Serum potassium | <0.001 | |||

| Low <3.1 mmol/L | 540 (1.2) | 127 (1.4) | 413 (1.2) | |

| Normal 3.1 – 5.3 mmol/L | 40345 (91.3) | 7980 (88.3) | 32365 (92.0) | |

| High >5.3 mmol/L | 3318 (7.5) | 927 (10.3) | 2391 (6.8) | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.7,1.4) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.3) | 1.1 (0.8, 2.0) | <0.001 |

| Most extreme blood glucose level | <0.001 | |||

| 2.2 – 3.8 or 10.1 – 16.6 mmol/L | 19234 (43.5) | 4101 (45.4) | 15133 (43.0) | |

| 3.9 – 10.0 mmol/L | 16128 (36.5) | 2842 (31.5) | 13286 (37.8) | |

| <2.2 or >16.6 mmol/L | 8841 (20.0) | 2091 (23.2) | 6750 (19.2) | |

| Urgent or emergent admission | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 38145 (86.3) | 8198 (90.8) | 29947 (85.2) | |

| No | 6058 (13.7) | 836 (9.3) | 5222 (14.9) | |

| Intensive care admission | 0.15 | |||

| Yes | 7078 (16.0) | 1498 (16.6) | 5580 (15.9) | |

| No | 37125 (84.0) | 7536 (83.4) | 29589 (84.1) | |

| DKA or HHS ever | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 3220 (7.3) | 918 (10.2) | 2302 (6.6) | |

| No | 40983 (92.7) | 8116 (89.8) | 32867 (93.5) | |

| Microvascular complications,b | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 30854 (69.8) | 5247 (58.1) | 25607 (72.8) | |

| 1 | 8227 (18.6) | 2095 (23.2) | 6132 (17.4) | |

| 2 | 3294 (7.5) | 1017 (11.3) | 2277 (6.5) | |

| 3 | 1828 (4.1) | 675 (7.5) | 1153 (3.3) | |

| Macrovascular complications,c | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 19301 (43.7) | 3223 (35.7) | 16078 (45.7) | |

| 1 | 12716 (28.8) | 2528 (28.0) | 10188 (29.0) | |

| 2 | 8840 (20.0) | 2218 (24.6) | 6622 (18.8) | |

| 3 | 2647 (6.0) | 840 (9.3) | 1807 (5.1) | |

| 4 | 699 (1.6) | 225 (2.5) | 474 (1.4) | |

| Schizophrenia or mood disorder ever | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 13112 (29.7) | 3436 (38.0) | 9676 (27.5) | |

| No | 31091 (70.3) | 5598 (62.0) | 25493 (72.5) | |

| Gastroparesis ever | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 2100 (4.8) | 770 (8.5) | 1330 (3.8) | |

| No | 42103 (95.3) | 8264 (91.5) | 33839 (96.2) | |

| Pancreatitis ever | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 2387 (5.4) | 710 (7.9) | 1677 (4.8) | |

| No | 41816 (94.6) | 8324 (92.1) | 33492 (95.2) | |

| Hypertension ever | 0.6 | |||

| Yes | 32532 (73.6) | 6681 (74.0) | 25851 (73.5) | |

| No | 11671 (26.4) | 2353 (26.1) | 9318 (26.5) | |

| COPD or asthma ever | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 10433 (23.6) | 2614 (28.9) | 7819 (22.2) | |

| No | 33770 (76.4) | 6420 (71.1) | 27350 (77.8) | |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias ever | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 10546 (23.9) | 2642 (29.3) | 7904 (22.5) | |

| No | 33657 (76.1) | 6392 (70.8) | 27265 (77.5) | |

| Malignant neoplasm ever | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 4406 (10.0) | 1166 (12.9) | 3240 (9.2) | |

| No | 39797 (90.0) | 7868 (87.1) | 31929 (90.8) | |

| Anemia ever | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 18264 (41.3) | 5128 (56.8) | 13136 (37.4) | |

| No | 25939 (58.7) | 3906 (43.2) | 22033 (62.7) | |

| Drug abuse | 0.045 | |||

| Never | 35424 (80.1) | 7104 (78.6) | 28320 (80.5) | |

| History | 6942 (15.7) | 1505 (16.7) | 5437 (15.5) | |

| Current | 1837 (4.2) | 425 (4.7) | 1412 (4.0) | |

Data are N (%) unless otherwise specified. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; HHS, hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome;

Pneumonia, urinary tract infection, septicemia, skin or subcutaneous infection;

Retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy;

Coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke, peripheral vascular disease; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Univariate analysis identified numerous factors associated with the risk of 30-d readmission (Table 1). Those not associated with 30-d readmission were a diagnosis of hypertension, pre-admission sulfonylurea use, admission to an intensive care unit, gender and age.

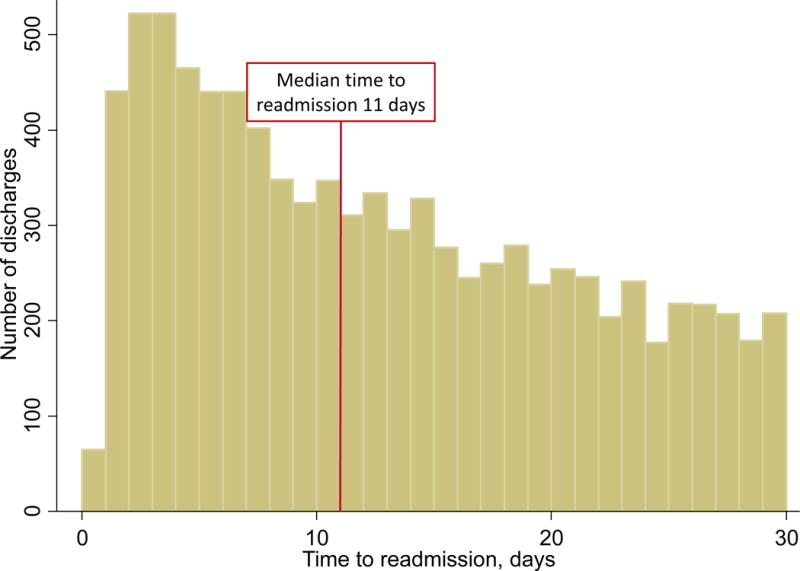

A total of 27 factors were found to be statistically significantly associated with 30-d readmission in multivariable analysis (Table 2). The most striking predictor was not having a follow up visit within 30 days after the index discharge, which was associated with a 5.74-fold increased odds of readmission [OR 5.74 (5.35-6.15) 95% CI]. The next strongest predictor was having a discharge within 90 days before the index admission, which was associated with 76% increased odds of readmission [OR 1.76 (1.64-1.89) 95% CI]. Females had 10% lower odds of readmission than males [OR 0.90 (0.84-0.96) 95% CI]. Blacks, Hispanics, and patients of other races/ethnicities were 10% [OR 0.90 (0.83-0.98) 95% CI], 14% [OR 0.86 (0.77-0.95) 95% CI] and 28% [OR 0.72 (0.62-0.83) 95% CI] less likely to be readmitted than whites. Disabled [OR 1.55 (1.35-1.78) 95% CI], retired [OR 1.46 (1.28-1.67) 95% CI], or unemployed [OR 1.26 (1.10-1.44) 95% CI] patients were at 26% to 55% greater odds of readmission than employed individuals. With respect to pre-admission diabetes therapy, insulin use was associated with 14% greater odds of readmission [OR 1.14 (1.06-1.22) 95% CI], while thiazolidinedione use was associated with 16% lower odds [OR 0.84 (0.75-0.95) 95% CI]. An extreme blood glucose value <40 or >300 mg/dL (<2.2 or >16.6 mmol/L) during hospitalization was associated with 20% greater odds of readmission [OR 1.20 (1.10-1.31) 95% CI]. Several admission laboratory values were associated with 30-d readmission: low or high white blood cell count (27% [OR 1.27 (1.12-1.45) 95% CI] or 19% increased odds [OR 1.19 (1.11-1.28) 95% CI]), low serum albumin (14% increased odds [OR 1.14 (1.07-1.22)]), low serum sodium (19% increased odds [OR 1.19 (1.10-1.30) 95% CI]), higher serum creatinine (8% increased odds per the log of a 1 unit increase [OR 1.08 (1.03-1.14) 95% CI]) and higher hematocrit (11% lower odds per 5% increase [OR 0.89 (0.86-0.92) 95% CI]). In addition to a high comorbidity burden according to the Charlson comorbidity index, several comorbidities were independently associated with a significantly increased risk of readmission, specifically, schizophrenia or a mood disorder, gastroparesis, cardiac dysrhythmias, anemia, and fluid or electrolyte disorders. Compared to those discharged home, patients discharged against medical advice (AMA) had 60% greater odds of being readmitted [OR 1.60 (1.32-1.94) 95% CI]. Similarly, being discharged AMA in the year prior to the index admission was associated with a 27% increased odds of being readmitted [OR 1.27 (1.03-1.58) 95% CI]. Discharges with longer LOS were more likely to be followed by a readmission than discharges with shorter LOS [OR 1.14 (1.09-1.19) 95% CI]. The C statistic was 0.82. Among the 30-d readmissions, the median time to readmission was 11 days (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Risk factors for all-cause 30-d readmission in multivariable modela

| Predictor | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| New Variables | ||

| Outpatient visit (vs. Yes) | ||

| No | 5.74 (5.35-6.15) | <0.001 |

| Not documented | 0.28 (0.25-0.31) | <0.001 |

| Discharge status of index admission (vs. Home) | ||

| Against medical advice | 1.60 (1.32-1.94) | <0.001 |

| Home with nursing care | 1.03 (0.95-1.11) | 0.46 |

| Sub-acute facility | 0.99 (0.91-1.08) | 0.90 |

| Other | 0.72 (0.51-1.01) | 0.054 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (vs. 0) | ||

| >6 | 1.38 (1.17-1.64) | <0.001 |

| 5 – 6 | 1.17 (0.98-1.39) | 0.083 |

| 3 – 4 | 1.17 (1.00-1.38) | 0.053 |

| 1 – 2 | 1.07 (0.91-1.26) | 0.39 |

| Length-of-stay (days)(log) | 1.14 (1.09-1.19) | <0.001 |

| Previously studied variables | ||

| Sociodemographic/Administrative | ||

| Employment status (vs. Employed) | ||

| Disabled | 1.55 (1.35-1.78) | <0.001 |

| Retired | 1.46 (1.28-1.67) | <0.001 |

| Unemployed | 1.26 (1.10-1.44) | <0.001 |

| Other or unknown | 1.09 (0.85-1.40) | 0.51 |

| Insurance status (vs. Private) | ||

| Medicaid | 1.17 (1.06-1.29) | 0.0015 |

| Medicare | 0.95 (0.88-1.0 ) | 0.25 |

| None | 0.77 (0.65-0.91) | 0.0029 |

| Home zip code <8 km from hospital | 1.11 (1.0 -1.20) | 0.0086 |

| Race/ethnicity (vs. White) | ||

| Black | 0.90 (0.83-0.98) | 0.014 |

| Hispanic | 0.86 (0.77-0.9 ) | 0.0049 |

| Other | 0.72 (0.62-0.83) | <0.001 |

| Female (vs. Male) | 0.90 (0.84-0.96) | 0.002 |

| Pre-admission clinical | ||

| Discharged within 90 days before admission | 1.76 (1.64-1.89) | <0.001 |

| Discharge status 1 year prior to index admission | ||

| Against medical advice | 1.27 (1.03-1.58) | 0.025 |

| Home with nursing care | 1.04 (0.95-1.13) | 0.37 |

| Sub-acute facility | 1.01 (0.93-1.11) | 0.77 |

| No discharge recorded | 0.91 (0.83-0.99) | 0.022 |

| Pre-admission glucocorticoid use | 1.16 (1.05-1.28) | 0.0048 |

| Pre-admission insulin use | 1.14 (1.06-1.22) | <0.001 |

| Pre-admission thiazolidinedione use | 0.84 (0.75-0.95) | 0.0034 |

| Hospital | ||

| Gastroparesis ever | 1.38 (1.18-1.63) | <0.001 |

| White blood cell count (vs. Normal) | ||

| Low <4.0 × 109 L | 1.27 (1.12-1.45) | <0.001 |

| High >11.0 × 109 L | 1.19 (1.11-1.28) | <0.001 |

| Serum sodium (vs. Normal) | ||

| Low <135 mmol/L | (1.10-1.3 ) | <0.001 |

| High >145 mmol/L | 1.06 (0.82-1.38) | 0.66 |

| Most extreme blood glucose level (vs. 3.9 – 10.0 mmol/L) | ||

| <2.2 or >16.6 mmol/L | 1.20 (1.10-1.31) | <0.001 |

| 2.2 – 3.8 or 10.1 – 16.6 mmol/L | 1.07 (1.00-1.1 ) | 0.038 |

| Urgent or emergent admission | 1.18 (1.08-1.29) | <0.001 |

| Serum albumin (vs. ≥40 g/L) | ||

| <40 g/L | 1.14 (1.07-1.22) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 0.94 (0.85-1.04) | 0.2 |

| Anemia ever | 1.15(1.07-1.24) | <0.001 |

| Schizophrenia or mood disorder ever | 1.12 (1.04-1.2 ) | 0.0022 |

| Current fluid or electrolyte disorder | 1.10 (1.03-1.18) | 0.0048 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias ever | 1.15 (1.06-1.24) | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL)(log) | 1.08 (1.03-1.14) | 0.0025 |

| Blood transfusion given | 0. (0.82-0.97) | 0.010 |

| Hematocrit (per 5% increase) | 0.89 (0.86-0.92) | <0.001 |

Adjusted for year of discharge

Figure 1.

Time to readmission among the 9,034 readmissions within 30 days of discharge (median 11, IQR 5 - 19 days). IQR, interquartile range

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective cohort study of 44,203 discharges of patients with diabetes, 48 sociodemographic, clinical and administrative variables were evaluated for associations with all-cause 30-d readmission. In multivariable analysis, numerous risk factors for 30-d readmission were identified. The strongest risk factors were as follows: lacking an outpatient visit after discharge, duration of hospital LOS, prior discharge within 90 days before the index admission, current or prior discharge AMA, employment status of disabled, retired, or unemployed, race/ethnicity, health insurance coverage, comorbidity burden, and abnormal admission laboratory values.

Model performance was very good based on a C statistic of 0.82.15 This is a considerable improvement over the C statistic of the DERRI, which was 0.70 in the training sample and 0.69 in the internal validation sample.8 The DERRI is a prediction tool designed for use in hospitalized patients prior to discharge. Therefore, it was based on information obtainable on the day of admission, was limited to as few predictors as possible, and did not include a comorbidity index. In contrast, the current study provides a more comprehensive analysis that describes both pre-discharge and post-discharge risk factors for 30-d readmission, as well as a comorbidity index to adjust for the burden of comorbid conditions. All the predictors contained in the DERRI were confirmed to be associated with readmission, independent of the numerous additional risk factors included in the model. Notably, variables based on post-discharge information, i.e., outpatient follow up, LOS, and discharge status, were highly associated with readmission risk.

Our model compares favorably to the performance of other models of readmission risk. The range of C statistic among models specifically developed in patients with diabetes is 0.64 to 0.82.9,10,16–18 A recent systematic review of models that predict 28-d or 30-d readmission of any patients reported a C statistic range of 0.21 to 0.88, with only 5 studies reporting a C statistic greater than 0.8.19

Of particular interest is the finding that an extreme high or low blood glucose level is associated with 30-d readmission. This confirms and extends previous work that showed a secondary hospital diagnosis of hypoglycemia was associated with 30-d readmission.20 To our knowledge, the only other study to examine inpatient glycemic control and readmission was in patients with diabetes hospitalized for heart failure.21 Increasing mean blood glucose and increasing A1c was associated with readmission for heart failure 30 to 90 days after hospital discharge.

Previous evidence on an association of race/ethnicity with readmission risk among patients with diabetes is conflicting, with some studies showing that blacks and Hispanics are at increased risk compared to whites and others reporting no difference in risk.5,7,9,16,17,22–24 Our finding that blacks and Hispanics had lower odds of readmission compared to whites adds to the conflicting evidence base. Differences in study populations and the specific sets of covariates analyzed may account for the different findings across studies.

Admission serum sodium, creatinine, albumin, white blood cell count and hematocrit were each independently associated with 30-d readmission, suggesting that admission laboratory values can provide important readmission risk information. Whether these tests function as markers of illness or are causally related to readmission remains unknown. Higher creatinine levels have been associated with readmission risk among patients hospitalized with heart failure.25 Inpatient laboratory tests have also been included in a readmission risk prediction model developed in unselected hospitalized patients in Maine, but the specific tests were not reported.26 We are unaware of other studies, most of which are based on administrative data, providing as extensive an evaluation of the relationship of inpatient laboratory values with 30-d readmission among patients with diabetes. Another risk factor that has not been reported among diabetes patients is receiving a blood transfusion, which was associated with lower odds of readmission. As with the laboratory tests, it is uncertain whether this factor causes readmissions.

The relationship between post-discharge outpatient follow-up and readmission among patients with diabetes has been uncertain, with prior studies reporting increased, decreased or U-shaped risk.10,16,24 We found that lack of an outpatient visit within 30 days was associated with a nearly 6-fold increased odds of readmission. This is consistent with a large study that reported more than half of Medicare patients who were initially hospitalized for a medical condition then readmitted within 30 days did not have outpatient follow up before the readmission.27 Absence of outpatient follow-up may reflect poor health literacy, socioeconomic barriers, and/or a poor state of health, all of which could contribute to readmission risk.28 Investigating reasons why patients fail to have outpatient follow-up may identify potential leverage points for intervention. It is worth noting that poor health literacy and social determinants of health are relatively unmodifiable, which raises questions about the extent to which hospitals should be penalized for excess 30-d readmission rates.

We found that 50% of 30-d readmissions occurred within 11 days after discharge. To our knowledge, time to readmission among patients with diabetes has not been previously reported. A study of unselected hospitalized patients in Maine found that more than 50% of patients readmitted within 30 days experienced readmission by 15 days post-discharge.26 Whether or not there is a difference in the timing of readmission between patients with and without diabetes remains unknown. Interventions to reduce readmission risk should take this timing into account.

There are a few limitations of this study of patients at a single urban academic medical center. Results may not be generalizable to other populations. Data on potential readmission risk factors such as hemoglobin A1c, diabetes type or duration, admitting service, and medications recommended upon discharge were not available. Furthermore, inferences about causality based on these retrospective, observational data are limited. Lastly, readmissions at other hospitals were not captured. However, it is unlikely that a substantial proportion of patients were readmitted elsewhere given that the readmission rate in the study sample is on the higher end of the range for reported readmission rates of patients with diabetes. These limitations are balanced by a relatively large sample size and a well-characterized population that allowed for the evaluation of numerous sociodemographic, administrative and clinical factors.

Whether identification of these risk factors can be translated into lower readmission risk for diabetes patients remains a key unanswered question. These findings may lead to 2 strategies for reducing readmission risk that hospitals could consider to reduce their exposure to financial penalties. One is improving currently available readmission risk prediction tools to identify higher risk patients for intervention. It is clear that adding risk factors to the DERRI would improve its predictive accuracy. Increasing the number of factors, however, would increase the burden on users to collect and enter the additional data. Tools based on more comprehensive models than the DERRI may require integration in electronic health record systems to be useable and practical at the point-of-care for individual patients. A potentially automatable claims-based algorithm to predict all-cause 30-day readmission among patients with type 2 diabetes has been reported,9 however, based on our findings, it is likely that adding clinical data would improve predictive accuracy.

The second way our findings may be translated into reducing readmission risk is by considering the risk factors that are both modifiable and plausible as causal agents. For example, statin therapy was associated with lower readmission risk, and perhaps this could be a consideration in favor of initiating a statin upon discharge. There is substantial opportunity for improving adherence to guidelines regarding statin therapy, as one study found that nearly half of patients with diabetes and 35% of patients with diabetes and a history of cardiovascular disease do not take a statin.29 Higher hematocrit levels and blood transfusion were associated with lower readmission risk, whereas a diagnosis of anemia was associated with higher risk. It is possible that managing anemia may confer protection against readmission, which could become a factor in favor of performing blood transfusion among patients who have borderline indications. Likewise, high or low blood glucose levels were associated with higher risk of readmission, and optimizing glycemic control may protect against readmission risk. Hospital discharge is an often missed opportunity to adjust diabetes therapy, and these data suggest another reason why diabetes therapy should be optimized at discharge.30 Given that lack of outpatient follow-up within 30 days was a very strong risk factor for readmission, it is plausible that receiving outpatient follow-up may reduce readmission risk. Patients with diabetes could be prioritized to receive outpatient follow-up within 10 days, based on the median time to readmission of 11 days. Improving outpatient follow-up is particularly attractive as an intervention for hospitals because it is more of a systems-based practice issue than the other more individual-level care issues discussed above. One small study of 100 indigent patients with diabetes suggests that post-discharge follow-up within 5 days of discharge may reduce readmission risk.31 Additional research, ideally adequately-powered randomized controlled trials, would be required to test these hypotheses.

In conclusion, this relatively large retrospective cohort study of patients with diabetes identified numerous risk factors for all-cause 30-d readmission in a model with very good discrimination. A number of previously reported risk factors were confirmed, and several novel risk factors were identified, including inpatient blood transfusion, admission albumin and white blood cell count, and use of statins and glucocorticoids. Post-discharge factors add to the predictive accuracy achieved by pre-discharge factors. Hospital readmission among patients with diabetes poses a large burden on healthcare systems and is associated with great personal and financial costs. A better understanding of readmission risk may ultimately lead to lowering that risk by improving interventions to reduce readmission risk as well as targeting of interventions to high risk patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

D.R. was supported by a Temple University Department of Medicine Junior Faculty Research Award and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23DK102963. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

D.R. received unrelated research support from AstraZeneca, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Footnotes

A.K. and H.Z. report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Abhijana Karunakaran, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, 3322 N. Broad ST., Ste 205, Philadelphia, PA 19140, Office: 215-707-4746, Fax: 215-707-5599.

Huaqing Zhao, Department of Clinical Sciences, Temple Clinical Research Institute, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Kresge West Bldg., Philadelphia, PA 19140, Office: 215-707-6139, Fax: 215-707-3160.

Daniel J. Rubin, Associate Professor of Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, 3322 N. Broad ST., Ste 205, Philadelphia, PA 19140, Office: 215-707-4746, Fax: 215-707-5599.

References

- 1.HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) 2015 http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp. Accessed February 1, 2016.

- 2.ADA. Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):1033–1046. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin DJ. Hospital Readmission of Patients with Diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(4):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0584-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albrecht JS, Hirshon JM, Goldberg R, et al. Serious Mental Illness and Acute Hospital Readmission in Diabetic Patients. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2012;27(6):503–508. doi: 10.1177/1062860612436576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enomoto LM, Shrestha DP, Rosenthal MB, et al. Risk factors associated with 30-day readmission and length of stay in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31(1):122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostling S, Wyckoff J, Ciarkowski SL, et al. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and 30-day readmission rates. Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology. 2017;3(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s40842-016-0040-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbins JM, Webb DA. Diagnosing diabetes and preventing rehospitalizations: the urban diabetes study. Med Care. 2006;44(3):292–296. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000199639.20342.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin DJ, Handorf EA, Golden SH, et al. Development and Validation of a Novel Tool to Predict Hospital Readmission Risk Among Patients With Diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(10):1204–1215. doi: 10.4158/E161391.OR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins J, Abbass IM, Harvey R, et al. Predictors of all-cause-30-day-readmission among Medicare patients with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017:1–28. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1330258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eby E, Hardwick C, Yu M, et al. Predictors of 30 day hospital readmission in patients with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective, case–control, database study. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2015;31(1):107–114. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.981632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Hoore W, Bouckaert A, Tilquin C. Practical considerations on the use of the Charlson comorbidity index with administrative data bases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1996;49(12):1429–1433. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furnival GM, Wilson RW., Jr Regressions by Leaps and Bounds. Technometrics. 1974;16(4):499–511. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MD, et al. Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data Using Generalized Estimating Equations: An Orientation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(4):364–375. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royston P, Moons KGM, Altman DG, et al. Prognosis and prognostic research: Developing a prognostic model. BMJ. 2009;338:b604. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett KJ, Probst JC, Vyavaharkar M, et al. Lower rehospitalization rates among rural Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes. J Rural Health. 2012;28(3):227–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rico F, Liu Y, Martinez DA, et al. Preventable Readmission Risk Factors for Patients With Chronic Conditions. J Healthc Qual. 2015:1–16. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000462674.09641.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei NJ, Wexler DJ, Nathan DM, et al. Intensification of diabetes medication and risk for 30-day readmission. Diabet Med. 2013;30(2):e56–62. doi: 10.1111/dme.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou H, Della PR, Roberts P, et al. Utility of models to predict 28-day or 30-day unplanned hospital readmissions: an updated systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011060. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zapatero A, Gomez-Huelgas R, Gonzalez N, et al. Frequency of hypoglycemia and its impact on length of stay, mortality, and short-term readmission in patients with diabetes hospitalized in internal medicine wards. Endocrine Practice. 2014;20(9):870–875. doi: 10.4158/EP14006.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dungan KM, Osei K, Nagaraja HN, et al. Relationship between glycemic control and readmission rates in patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure during implementation of hospital-wide initiatives. Endocr Pract. 2010;16(6):945–951. doi: 10.4158/EP10093.OR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen HF, Popoola T, Radhakrishnan K, et al. Improving diabetic patient transition to home healthcare: leading risk factors for 30-day readmission. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(6):440–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang HJ, Andrews R, Stryer D, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in potentially preventable readmissions: the case of diabetes. American journal of public health. 2005;95(9):1561–1567. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raval AD, Zhou S, Wei W, et al. 30-Day Readmission Among Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries with Type 2 Diabetes. Population Health Management. 2015;18(4):256–264. doi: 10.1089/pop.2014.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krumholz HM, Chen YT, Wang Y, et al. Predictors of readmission among elderly survivors of admission with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2000;139(1 Pt 1):72–77. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hao S, Wang Y, Jin B, et al. Development, Validation and Deployment of a Real Time 30 Day Hospital Readmission Risk Assessment Tool in the Maine Healthcare Information Exchange. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin DJ, Donnell-Jackson K, Jhingan R, et al. Early readmission among patients with diabetes: a qualitative assessment of contributing factors. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications. 2014;28(6):869–873. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stark Casagrande S, Fradkin JE, Saydah SH, et al. The Prevalence of Meeting A1C, Blood Pressure, and LDL Goals Among People With Diabetes, 1988–2010. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2271–2279. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffith ML, Boord JB, Eden SK, et al. Clinical inertia of discharge planning among patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):2019–2026. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seggelke SA, Hawkins RM, Gibbs J, et al. Transitional care clinic for uninsured and medicaid-covered patients with diabetes mellitus discharged from the hospital: a pilot quality improvement study. Hosp Pract (1995) 2014;42(1):46–51. doi: 10.3810/hp.2014.02.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.