Background

The United States is amidst a drug overdose epidemic of unprecedented proportion. In 2016, there were an estimated 64,000 drug overdose fatalities, the majority of which involved opioids.1 Naloxone, the short-acting opioid antagonist used to reverse the effects of opioid overdose, has been distributed to people who inject drugs through community based organizations and syringe exchanges for nearly two decades. In this context, naloxone is typically prescribed via a standing order, enabling non-physicians to furnish naloxone to individuals at risk for experiencing or witnessing an opioid overdose. Naloxone distribution programs have proven to be widely successful: people who use drugs can be trained to respond to overdoses effectively2,3 and between 1996 and 2014, organizations across the US distributed over 152,000 naloxone kits to laypersons and received reports of over 26,000 overdose reversals.4 Furthermore, naloxone is associated with a reduction in heroin use among naloxone recipients5 and a population-level reduction in overdose mortality.6–13 Every US state has some legislation supporting naloxone access.14

The demographics of individuals at risk for opioid overdose has expanded since 2000 to include people who use prescription opioids who may not utilize community based services or syringe exchanges and thus may not have easy access to naloxone through standard means of distribution. Furthermore, syringe exchanges and harm reduction services may be difficult to access for individuals living in non-metropolitan areas. Thus, expanding naloxone availability through diverse mechanisms is considered an important component of overdose prevention, with primary care access a potentially valuable intervention. In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends that naloxone be co-prescribed to patients receiving opioids for chronic pain with risk factors such as receipt of more than 50 morphine milligram equivalents, concurrent benzodiazepine use, or a history of substance use disorder.15 Despite this federal endorsement, naloxone prescribing is still a relatively nascent intervention in primary care. This systematic review aims to assess the acceptability and feasibility of prescribing naloxone to patients in primary care settings.

Methods

Search Methodology

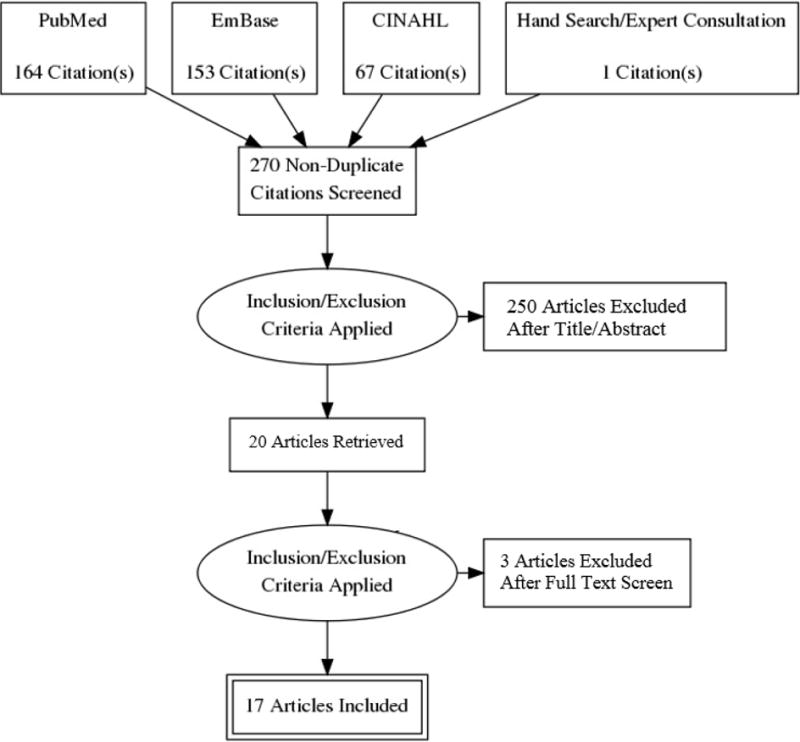

This review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines and was registered in PROSPERO prior to initiation. We queried PubMed, EmBase and CINAHL using the following Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms: (naloxone) AND (primary health care OR primary care nursing OR primary care physician). A complete list of database search terms can be found in Appendix 1. Database searches were conducted in October 2017, yielding 270 unduplicated articles. In addition to formal database searches, we hand searched citations from the eligible articles and consulted experts in the field to identify articles not found through our initial searches, adding one additional article to our results. Search results were exported to a reference manager, Mendeley Ltd., and then into Microsoft Excel (2013) for analysis. A PRISMA diagram illustrates the article selection process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA study selection flow diagram

Inclusion Criteria

Articles were included in our analysis if they discussed the acceptability or feasibility of prescribing naloxone to patients in a primary care setting. The search was limited to US-only peer-reviewed, full-length articles that were written in English and based on original research. There was no restriction on publication date. Articles could include patient, provider or medical staff perspectives, could be evaluation or feasibility studies, and could use either qualitative or quantitative analytic methods. Articles were excluded if they focused on prescribing naloxone outside of a primary care setting (e.g. standing order or prescribing through an emergency department).

Article Selection and Review

One analyst (EB) reviewed the titles of all queried articles. Articles that clearly did not pertain to the topic of this systematic review were excluded immediately (e.g. articles referring to the co-formulation of buprenorphine/naloxone). We eliminated 218 articles based on title review. One reviewer (EB) then independently reviewed the remaining 52 abstracts for inclusion. If eligibility was unclear, the reviewer consulted a second reviewer (PC) for a final decision. After title and abstract review, 20 articles met inclusion criteria.

Two analysts (EB and RB) then independently read the full-text of the eligible articles and recorded general information such as date, location, study design, study sample, research question, and primary study outcomes. Additionally, reviewers also collected data relating to either the acceptability or feasibility of naloxone prescribing, depending on the study’s primary purpose. Three articles were excluded during this phase; two did not meet inclusion criteria upon reading the complete text and one did not have full-text availability. We conducted a quality assessment of the eligible articles, however due to a high degree of heterogeneity in study design and inconsistencies in study metrics, we did not include the assessment in our results.

Analysis

To assess acceptability, we evaluated the articles for providers’ awareness and willingness to prescribe naloxone, attitudes, and anticipated barriers/concerns. To assess feasibility, we evaluated the articles for descriptions of programmatic implementation (e.g. training process, patient identification, naloxone formulation, ordering and dispensing processes, insurance and billing, and any streamlining or clinic based support), education (e.g. how were providers educated, was education provided to patients and by whom, and were educational materials distributed), attitudes, and experienced challenges. We report acceptability findings first, as many acceptability studies occurred prior to program implementation and feasibility results.

Results

Seventeen articles met our inclusion criteria and were included in this analysis (Table 1). Articles were categorized as either pertaining to naloxone prescribing acceptability (N=10),16–25 feasibility (N=5),26–30 or both (N=2),31,32 and also categorized as including perspectives from prescribers (N=14),16,18–22,24–31 patients (N=2),17,23 or both (N=1).32 The studies had broad geographic scope within the US, covering the Northeast (N=4), Midwest (N=1), Southwest (N=5), West (N=5), and national (N=2).

Table 1.

Articles Included in Systematic Review (N=17)

| Article | Location | N | Study Sample | Study Design | Primary research question | Summary of Key Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | Behar 201716 | California | 111 | Prescribers (MD, NP, PA) | Program evaluation | Is prescribing naloxone in primary care setting to patients on long-term opioids acceptable among primary care providers? | 79% of providers prescribed naloxone (mean 7.7 pts); 99% were likely to prescribe in future; concerns were largely administrative; internists and providers with more patients on long-term opioids were significantly more likely to prescribe naloxone; providers did not think prescribing naloxone would affect their opioid prescribing |

| Behar 201617 | California | 60 | Patients on long-term opioids (≥3 months) for chronic non-cancer pain | Program evaluation | Is receiving a naloxone prescription in a primary care setting acceptable among patients on long-term opioids for chronic non-cancer pain? | 90% of patients had not previously received naloxone; 97% believed naloxone should be prescribed for pain patients; 79% had positive/neutral response to being prescribed naloxone; 37% reported beneficial behavior change due to naloxone prescription; generally patients believed their risk of overdose was low; term “overdose” may be problematic and providers may want to use patient-centered language like “bad reaction” | |

| Beletsky 200718 | US - National | 588 | Physicians (MDs) | Postal surveys | What are primary care providers’ knowledge and willingness to prescribe naloxone to people who inject drugs? | 23% of physicians were aware of naloxone prescribing; 54% never consider prescribing. Age, having more patients on panel who injected drugs, having better attitudes towards people who inject drugs, and having confidence in one’s ability to help people who inject drugs were associated with a higher likelihood of prescribing naloxone. | |

| Binswanger 201519 | Colorado | 56 | Physicians, nurses, pharmacists and administrators | Focus groups | What are the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs around overdose education and naloxone prescribing among clinical staff in primary care settings? | Providers believed prescribing naloxone could save lives and result in safer opioid use. Providers noted knowledge gaps around naloxone in outpatient setting, concerns about identifying who to prescribe to, concerns about logistical barriers, fear of offending patients, and fear of risk compensation. | |

| Coffin 200320 | New York | 363 | Prescribers (MD, NP, PA) | Postal surveys | Are prescribers willing to prescribe naloxone to patients at risk of an opiate overdose? | 33% prescribers said they would consider prescribing, 29% were unsure and 37% said they would not prescribe naloxone to patients at risk of an opioid overdose. | |

| Gatewood 201621 | Maryland | 30 | Physicians and medical students | In-person interviews and focus groups | What are perceived barriers to naloxone prescribing to third-party contacts of opioid users among physicians and medical students? | Physicians and medical students identified three categories of concerns for prescribing naloxone to potential witnesses related to naloxone itself (e.g. duration of action, medical risks, route of administration etc.), providers (lack of knowledge or experience, medical community common practices and norms, insufficient provision of third-party education etc.), and patients (increased risk-taking behaviors, opioid withdrawal symptoms, decrease contact with medical staff etc.). | |

| Green 201322 | Connecticut and Rhode Island | 24 | Emergency department providers, substance use treatment providers, pain specialists and primary care providers | In-person interviews | What are the main barriers and facilitators around prescribing naloxone to pain patients and people who use drugs? | Overall, there was support for prescribing naloxone. Three main categories of concern emerged: risk compensation; identifying appropriate patients; and making sure naloxone was not a stand-alone approach. | |

| Mueller 201723 | Colorado | 24 | Patients prescribed high dose opioids (≥100 morphine mg equivalent daily dose) fir chronic non-cancer pain | In-person interviews | What are the attitudes towards naloxone prescribing among patients prescribed long-term opioids for non-cancer pain? | Positive narratives included patients receiving education around naloxone, and providers using empowering, non-judgmental language when discussing naloxone. Negative narratives included limited education around naloxone, medication costs, belief that overdose was caused by medication misuse, and fear that providers may think patients were misusing opioids if they accepted the naloxone prescription. | |

| Wilson 201624 | Maryland | 97 | Internal medicine resident physicians | Needs assessment | What are resident physicians’ knowledge around overdose risk, naloxone prescribing practices, attitudes related to naloxone, and barriers to overdose prevention and naloxone prescribing? | Resident physicians were largely aware of naloxone and were willing to prescribe it; barriers included needing more education around how to prescribe and support around identifying appropriate patients for a naloxone prescription. | |

| Winograd 201725 | Missouri | 45 | Prescribers (MD, NP, PA, and clinical pharmacists) | Surveys | What are prescribers’ knowledge and concerns around prescribe naloxone within the VA healthcare medical treatment setting? | Prescribers cited four primary categories of concern: lack of knowledge, iatrogenic effects, impressions of unsafe opioid prescribing, and risks of naloxone prescribing. Providers endorsed providing overdose education to patients. System-wide naloxone prescribing rates and sources increased over 320% following the initiation of overdose education and naloxone distribution expansion efforts. | |

| Both | Wilson 201731 | North Carolina | 1297 | Patient electronic medical charts | Program evaluation and surveys | What is the process of designing and implementing a targeted naloxone coprescribing program for patients on long-term opioid therapy in a primary care setting? | A chart abstraction prior to the implementation of a naloxone program showed that 49% of patients on chronic opioids met their criteria for naloxone, however only 3% had naloxone on their medication list. Pharmacists may be well-positioned to develop a targeted naloxone coprescribing program in primary care settings. |

| 26 | Physicians and resident physicians | ||||||

| Han 201732 | Pennsylvania | 16 | Patients | Program evaluation | Can a counseling intervention improve provider and patient awareness of naloxone, increase naloxone prescribing and prevent opioid overdose? | 97 naloxone kits were dispensed, largely for illicit opioid use. Five patients reported successfully using naloxone to reverse an overdose. Physicians and resident physicians noted improved knowledge around naloxone prescribing, and increased professional satisfaction caring for patients requesting opioids. Patients endorsed high levels of comfort discussing opioid use with their primary care physician. | |

| 22 | Physicians and resident physicians | ||||||

| Feasibility | Behar 201726 | California | 40 | Prescribers (MD, NP, PA) | Program evaluation | Is academic detailing an effective educational intervention to increase naloxone prescribing among primary care providers? | Academic detailing addressing opioid safety and naloxone prescribing was well-received by primary care providers and associated with an 11-fold increase in naloxone prescriptions filled by Medi-Cal patients among providers who received academic detailing compared to those who did not. |

| Coffin 201627 | California | 1,985 | Patients receiving long-term opioids (≥3 months) for chronic non-cancer pain | Nonrandomized intervention study | Is implementing a naloxone coprescribing program in primary care settings feasible and effective? | Naloxone can be co-prescribed to primary care patients on long-term opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. 38% of 1,985 patients receiving opioids were prescribed naloxone. Patients who received a naloxone prescription had 47% fewer opioid-related ED visits in the 6 months after receipt of the prescription (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.53 [95% CI, 0.34 to 0.83]; P = 0.005) and 63% fewer visits after 1 year (IRR, 0.37 [CI, 0.22 to 0.64]; P < 0.001) compared with patients who did not receive a naloxone prescription. When advised to offer naloxone to all patients receiving opioids, providers may prioritize those with established risk factors. Providing naloxone in primary care settings may have ancillary benefits, such as reducing opioid related adverse events. | |

| Devries 201728 | California | 252 | Prescribers (MD, NP, PA, and pharmacist) | Program evaluation | Is implementing a naloxone coprescribing program in primary care settings feasible and effective? | 252 physicians, pharmacists and nurses were trained in overdose education and take-home naloxone. Naloxone prescribing increased from a baseline of 4.5 per month to an average of 46 per month during the 3 months following implementation of the program. | |

| Oliva 201729 | US - National | 142 | Veterans Health Administration Medical Facilities | Quality improvement project | Is implementing a naloxone coprescribing program in primary care settings feasible and effective? | The Veterans Health Administration dispensed 45,178 naloxone prescriptions written by 5,693 prescribers to 39,328 patients who were primarily prescribed opioids or had opioid use disorder. There were 172 reported opioid overdose reversals using the prescribed naloxone at the time of reporting. | |

| Takeda 201630 | New Mexico | 164 | Patients on long-term opioids for chronic non-cancer pain | Observational study | Can naloxone prescribing be implemented in primary care settings using a universal precautions model? | 164 patients were enrolled in the study; all subjects were educated around opioid overdose risks and provided naloxone. No overdoses occurred in the study population. 57% of the cohort had depressive disorder, the median MED was 90mg/day, and the median Current Opioid Misuse Measure score was 5.0. The ambulatory co-prescribing of naloxone in a Universal Precautions model for all patients prescribed chronic opioid therapy could be adopted as a useful public health intervention. |

All studies assessing the acceptability of naloxone prescribing obtained data through surveys, interviews or focus groups. Analytic methodology varied and included quantitative, qualitative and mix-methods approaches. The time period for these studies ranged from 2001-2017. Feasibility studies focused largely on program evaluation studies and quantitative or mixed-methods analyses, with a time period ranging from 2013-2017. Three papers explored the acceptability of naloxone prescribing from a patient perspective, using quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods approaches.

ACCEPTABILITY OF NALOXONE PRESCRIBING

Willingness to prescribe naloxone (N=6)

Six articles directly assessed providers’ willingness to prescribe naloxone.16,18,20,22,24,31 The two earliest published articles reported the highest degree of provider resistance to naloxone prescribing. One study, published in 2003, stated that 37% of respondents would not be willing to prescribe naloxone20 while another study, published in 2006, stated that 54% of respondents would not prescribe naloxone.18 In contrast, the two most recent studies, published in 2016 and 2017, indicated that 90% and 99% of prescribers were willing to prescribe naloxone, respectively.16,24

In addition to acceptability among providers of the act of prescribing naloxone, a number of papers also noted potential ancillary benefits of prescribing naloxone to patients. In one paper, a provider stated:

“I expected the decreases in death from overdose – but I hadn’t thought about how this simple act of prescribing potentially lifesaving treatment has opened up other important conversations that have allowed me to provide better, safer and more compassionate care to my patients.”16

Receiving education around naloxone may impact providers’ acceptability of the intervention. Han, et al., for example, reported a statistically significant increase in providers’ comfort prescribing naloxone after receiving education.32 Results from another study showed that providers who had received naloxone education were 11 times more likely to prescribe naloxone to their patients compared to providers who had not received education.26 In addition, Wilson, et al., showed that most resident physicians in their sample (88%) believed it was their responsibility to educate their patients on overdose and naloxone utilization.24

Concerns related to naloxone prescribing (N=9)

While results suggest a secular trend of increasing willingness to prescribe naloxone in primary care settings, there remain potential barriers. Concerns referenced by seven of the nine studies16,19,21,22,24,25,31 include: lack of knowledge around prescribing naloxone, lack of knowledge around educating patients, and inability to identify patients eligible for naloxone. In one paper, a provider explained the concern around lack of knowledge: “I probably just don’t have quite as much knowledge about the outpatient safety of it to feel comfortable prescribing it right now.”19 Additional concerns included fear of risk compensation, fear of offending patients, and that prescribing may take too long. (Table 2) A provider reported concern around time due to the complicated nature of the patient population: “I don’t think I’d have the time, no…these patients are [the] most time consuming patients.”19 A pharmacist from the same study voiced concern around fear of offending patients: “I feel that patients would be almost offended, like, oh, you’re singling me out and I’m cherry picked to do this.”19 Other studies refuted similar barriers. For instance, Wilson, et al., reported that 86% of resident physicians did not believe naloxone enabled risky behavior24 and Behar, et al., reported that the majority of providers did not believe their patients would react poorly if offered a naloxone prescription.16

Table 2.

Barriers to Naloxone Prescribing

| (N=9 articles) | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Patient concerns | ||

| Risk compensation | 4 | 44% |

| Naloxone alone not adequate overdose response | 2 | 22% |

| Fear of decreased contact with medical providers/less likely to seek treatment | 2 | 22% |

| Provider concerns | ||

| Fear of offending patients | 3 | 33% |

| Fear of appearing to condone opioid misuse | 2 | 22% |

| Introspection on prescribing practices | 1 | 11% |

| Liability in naloxone prescribing | 1 | 11% |

| Logistical concerns | ||

| Lacking knowledge to prescribing naloxone | 6 | 67% |

| Identifying patient eligibility for naloxone | 5 | 56% |

| Educating patients | 6 | 67% |

| Prescribing takes too much time | 3 | 33% |

| Prescribing should be done by someone else | 1 | 11% |

| Privacy and confidentiality concerns | 1 | 11% |

| Remembering to prescribe and follow up | 1 | 11% |

| Lack of awareness around prescribing | 1 | 11% |

| Billing/cost issues | 1 | 11% |

| Limited availability of naloxone | 1 | 11% |

| Naloxone concerns | ||

| Route of administration | 2 | 22% |

| Difficult assembling device | 2 | 22% |

| Duration of action | 1 | 11% |

| Medical risks | 1 | 11% |

| Expiration date | 1 | 11% |

FEASIBILITY OF IMPLEMENTING A NALOXONE PRESCRIBING PROGRAM

Seven studies provided information around the implementation process of their naloxone prescribing program. Four main components of program implementation emerged throughout the studies, including: training providers to prescribe naloxone, indications for naloxone prescribing, training providers to educate patients on naloxone, and logistics of filling the prescription.

Overall feasibility of naloxone prescribing (N=6)

Studies assessing feasibility demonstrated that naloxone prescribing in primary care practice is feasible. After training physicians, pharmacists, and nurses, one study saw the number of prescriptions for naloxone increase from a baseline of 4.5 prescriptions per month to 46 per month during the three-month follow up.28 Oliva, et al., reported significant uptake in naloxone prescribing, with over 45,000 naloxone prescriptions written by over 5,600 providers to 39,328 patients who were prescribed opioids or who had an opioid use disorder.29 In addition to being feasible, naloxone prescribing may also be effective at reducing opioid-related adverse events, as Coffin, et al., demonstrated that patients who had received naloxone had 63% fewer opioid-related emergency department visits one year after receiving a naloxone prescription compared to those who did not receive naloxone.27

Additionally, one provider suggested that naloxone prescribing may help to adjust the culture of opioid prescribing and use in primary care:

“I was sort of hoping that if we implement a good program where even at initiation [of opioids], we talk about overdose prevention and naloxone, that it will bring, you know, the safety concerns to the forefront, and then it might actually help people understand that these are potentially lethal medications, and I feel like that might be one of the things that might be most beneficial from it… just re-setting of, like, the culture around these medications [opioids] as much as, you know, potentially saving someone’s life from overdose.”19

Training providers to prescribe naloxone (N=5)

All five studies reported at least some in-person training, while a few studies also reported supplemental electronic28 or video-based29 education. Trainings were offered to prescribers in all studies, with some also offering trainings to pharmacists, resident physicians, medical students, and other clinic staff. The majority of trainings were conducted by pharmacists followed by prescribers and staff from local health departments. All studies trained prescribers on how to educate patients on naloxone and opioid overdose. The majority reported also trained prescribers on how to write a naloxone prescription, indications for prescribing, and methods of naloxone administration (Table 3). Only three studies documented training length, which ranged from 5-60 minutes.26–28 Two studies described their approach to education as academic detailing.26,29 Some studies discussed soliciting support from a “clinic champion” to help raise awareness and garner support for naloxone prescribing.32,27

Table 3.

Content of provider education

| (N=6 articles) (all that apply) | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| How to educate patients on naloxone and opioid overdoses | 6 | 100% |

| Instructions for how to write a naloxone prescription | 5 | 83% |

| Indications for prescribing naloxone | 4 | 67% |

| Method of naloxone administration | 4 | 67% |

| Rationale for furnishing naloxone | 3 | 50% |

| Naloxone prescribing laws | 3 | 50% |

| Patient-level opioid overdose risk factors | 3 | 50% |

| Background on overdose | 2 | 33% |

| Background on naloxone (pharmacokinetics, effectiveness etc) | 2 | 33% |

| Payer/pharmacy coverage | 2 | 33% |

Indications for prescribing naloxone (N=7)

While we can identify certain risk factors for overdose (e.g. having previously experienced an overdose,34,35 periods of abstinence,36–38 and concomitant benzodiazepine use39,40), there is limited research suggesting that we can adequately predict risk factors for developing an opioid use disorder or experiencing an opioid overdose among patients on chronic opioids; to-date the studies validating risk assessment tools are retrospective.41–43 As a result, the majority of studies recommended a universal naloxone prescribing model for patient on long-term opioids (≥3 months) for chronic non-cancer pain or otherwise at risk of experiencing an overdose.26,27,29,30 In one paper, a pharmacist advocated for universal prescribing for patients on long-term opioids stating, “…logistically it’s hard to reach out to every patient, but if the goal is to save lives, you have to bring it up to everybody.”19 Similarly, a provider from the same study grappled with determining naloxone eligibility, ultimately suggesting universal prescribing may be the best approach:

“I had a patient whose daughter accidentally overdosed on her meds, so, I’m wondering, shouldn’t we be offering it [naloxone] more broadly? Do we have this discussion with everybody and then offer to write the prescription for those who are accepting of it?”19

Three studies provided additional guidance around patient eligibility, including indications of primary risk factors (such as concomitant benzodiazepine use, recent period of abstinence etc.) but ultimately also noted that the decision could be based on provider discretion or at a patient’s request.28,31,32

Patient education (N=7)

While all seven studies provided some component of patient education around naloxone prescribing, the content and duration varied. There was only one study in which prescribers themselves did not provide education directly to patients.30 Some studies also utilized additional clinic staff to conduct education, including pharmacists, medical and pharmacy students, medical assistants, and research associates. Five studies26,28,29,32,27 offered patients the same or an adapted version of a tri-fold brochure around overdose and naloxone (Appendix 2), while the remaining two used different materials with similar messaging. Four studies26,30,32, 27 explicitly advised that patients’ caregivers, family members, or friends be included in the naloxone training if possible, though none required that such persons be present.

Filling the naloxone prescription (N=7)

Naloxone formulation was largely determined by medication availability and payer coverage at the time studies took place. All studies provided an option to prescribe an off-label intranasal naloxone device, four studies also offered the intramuscular device,26,28,29,27 three offered the auto-injector,26,28,29 and one offered the FDA-approved nasal spray.29 Two studies systematically implemented an alert in their electronic health record (EHR) to assist providers in naloxone prescribing,28,32 one of which also included a link in their EHR to patient educational materials. Two studies dispensed naloxone to patients onsite,30,32 while all other studies relied on pharmacy pick-up. All studies billed patients’ insurance for the naloxone.

PATIENT PERSPECTIVES

Of the three studies focused on patient perspectives, two presented results from patients who had received a naloxone prescription;17,32 the remaining study solicited perspectives from patients who were on long-term opioids but did not include data on whether patients had been offered a naloxone prescription.23

Naloxone acceptability and utilization (N=3)

Overall, study results suggest that patients had little prior knowledge of naloxone. One paper from a metropolitan area with high rates of lay naloxone distribution reported that 36 of 60 interviewees (60%) had never heard of naloxone prior to being offered a prescription, though 95% were willing to receive the prescription again in the future and 97% believed it should be prescribed to some/all patients on long-term opioids in a primary care setting.17 Two studies17,32 reported that the majority of patients felt an increased sense of security after receiving naloxone, and one noted that 37% of patients reported beneficial behavior changes after receiving the prescription with no hazardous behavior changes reported.17 Studies also confirmed that the majority of patients were comfortable and willing to administer naloxone if needed.17,32 One study reported that 5 patients (5%) who received naloxone had used it,32 and another reported that 3 of 60 patients (5%) stated that the naloxone they were prescribed by their provider was used on them.17

Facilitators/benefits and barriers/concerns (N=3)

Two papers presented facilitators and perceived benefits around naloxone prescribing. In Behar, et al., patients discussed benefits of receiving naloxone, including: benefits to the community, appreciating it was offered, and improving their relationship with their provider.17 Mueller, et al. noted facilitators, including: providers’ using empowering and non-judgmental communication, framing naloxone for use in “worse case scenarios”, and providing education and training around opioids and naloxone.23 Framing naloxone as a safety precaution for an unexpected situation resonated with patients in Mueller, et al, as one patient stated:

“It’s like a seatbelt. You don’t plan on getting in an accident but if you do it’s good to have the seat belt. I can see the fire extinguisher analogy…it doesn’t mean you’re going to go set a fire, but it’s [naloxone] there just in case so it could save lives.”23

Similarly, in Behar, et al., a patient shared similar sentiments about receiving naloxone:

“I thought [naloxone] was a wonderful idea…I have been on a reasonably high dose for many years and have never overdosed, but there have been at least 1 or 2 times where I’ve [said], ‘Oh, wait, I just took a pill 20 minutes ago and I just took another…oops!’ It can happen to anybody.”17

Mueller, et al. also noted barriers to naloxone receipt, including: fear of exacerbating providers’ concerns of opioid misuse if the naloxone prescription was accepted, fear of loss of opioids for pain management, and concerns around medication costs.23 One patient expressed concern around the perception of accepting a naloxone prescription:

“[The] thing about it [accepting naloxone] is that you are giving the signal that you believe that you are going to intentionally overdose because you’re already saying I’m going to overdose, I need something for it.”23

Because Mueller, et al. did not report if patients had been offered a naloxone prescription, it’s unclear if these barriers are based on patients’ real experiences or expectations. Behar, et al. reported that a minority of patients had negative reactions to being offered a naloxone prescription, most commonly due to: feeling the prescription was unnecessary, feeling judged, or being scared.17 An additional potential barrier presented in the studies is that patients believed they were at low risk for overdose, commonly attributing this to the fact that their opioids were prescribed by their physician. A patient articulated this concern by stating, “…I only take it as prescribed…I don’t abuse my medication so why would I need [naloxone]?”23

Framing an educational message (N=2)

Messaging around overdose and naloxone may influence patients’ interpretation and willingness to accept a naloxone prescription and understand its utility. In Mueller, et al. one patient offered two different explanations for naloxone prescribing, stating:

“Well, I guess you could look at it two ways. You could look at it as well, you know, if [an overdose] should accidentally happen, [naloxone] would be a good thing, or you could think, ‘Well, do they think I’m at risk for [misusing my medications]?…or are they doing this more out for my protection?’”23

When framed positively, patients may be willing to accept naloxone. A patient from the same study, after learning about naloxone, said:

“If I had not heard what your description [of naloxone] was, I would probably almost be offended or something. I might be like you think I’m abusing them [my medications].”23

Using strategic educational messaging was also considered important by authors of one paper that found 37% of interviewees had personally experienced an opioid-poisoning event, yet 45% of these respondents described the event as a “bad reaction” not an overdose.17 Based on this, the authors suggested replacing the term “overdose” with patient-centered language such as “bad reaction” or “accidental overdose” to increase patient comprehension. Results from these studies suggest that patient-centered language may be important to minimize barriers to patient acceptance of naloxone.

Discussion

We found that prescribing naloxone in primary care settings is generally an acceptable and feasible intervention among both providers and patients.

Providers’ willingness to prescribe naloxone to patients appears to have increased over time from the early 2000s to today, parallel to increasing attention and concern regarding the opioid crisis. This apparent shift may be due to increased awareness around naloxone prescribing, increased empowerment among providers to address opioid safety, and/or the advent of simpler naloxone formulations intended for lay use. Nevertheless, providers still noted a number of barriers affecting their willingness and/or ability to prescribe naloxone.

Most program evaluation studies reported on formal clinic-wide naloxone prescribing programs, as opposed to passive recommendations to prescribe naloxone. Rationales for implementing a structured program include: (1) naloxone prescribing is still novel in many primary care settings and there are currently no formal, national guidelines on how to integrate naloxone into primary care practice, (2) historically there have been logistical barriers to prescribing such as obtaining atomizers for the off-label intranasal naloxone device, and (3) a formal program links naloxone prescribing to broader opioid stewardship efforts enacted on a clinic-wide scale. As clinic-based naloxone prescribing becomes more widespread, it may allow the intervention to become an integrated part of panel management without the need for formal programming. In the meantime, such as with other preventative interventions like vaccinations and cancer screenings, clinic-wide programs can offer essential reminders, support, and instruction for providers for whom it is not yet part of standard care. Overall, there was considerable diversity between the programmatic models represented in the studies, suggesting that programs can adapt and modify implementation approaches to best fit clinic needs.

Implementing a universal prescribing model – as used in many studies in this review – could be useful for integrating naloxone into standard clinical practice as it may alleviate complicated decision making processes for providers and quell concerns around evaluating patients’ risk for overdose, remembering who to prescribe to, and singling out or offending patients. Furthermore, a universal model may help decrease stigma and initiate communication between providers and patients around opioid use, overdose risk, and pain management. There may, however, be limitations to a universal prescribing approach, including medication cost and clinic resources. Naloxone prescribing may benefit from being paired with an educational, counseling or interpersonal intervention, as results suggest that the act of prescribing naloxone itself could have ancillary benefits related to safer opioid use behaviors. Further research is needed to determine both the optimal indications for naloxone and the efficacy of naloxone prescribing in decreasing overdose among patients prescribed opioids and their immediate social networks.

Limitations

This systematic review has limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small and is limited only to US published studies. Methodological limitations of the studies (e.g. most were descriptive or observational) prevented us from assessing the efficacy of naloxone prescribing in primary care, although assessing naloxone prescribing with more rigorous study designs such as randomized-controlled trials is challenged by substantial logistical and ethical barriers. Some papers in this review focused solely on providers and patients participating in naloxone programs and may therefore not have capture opinions of those not engaged in or aware of naloxone prescribing programs which could bias our results. Finally, this review may not be comprehensive as it only includes published studies, thereby excluding naloxone prescribing interventions that have not been published.

Conclusions

Naloxone prescribing in a primary care setting is an acceptable and feasible intervention. Primary care is a strategic point of naloxone distribution as it may help destigmatize the medication, connect it to larger opioid stewardship efforts, and expand access to individuals who may otherwise lack awareness or access.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided through the National Institutes of Health grant K24DA042720

References

- 1.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose Death Rates | National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Published 2017. Accessed October 21, 2017.

- 2.Green TC, Heimer R, Grau LE. Distinguishing signs of opioid overdose and indication for naloxone: an evaluation of six overdose training and naloxone distribution programs in the United States. Addiction. 2008;103(6):979–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAuley A, Lindsay G, Woods M, Louttit D. Responsible management and use of a personal take-home naloxone supply: A pilot project. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2010;17(4):388–399. doi: 10.3109/09687630802530712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ. Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons - United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(23):631–635. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26086633. Accessed April 21, 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seal KH, Thawley R, Gee L, et al. Naloxone distribution and cardiopulmonary resuscitation training for injection drug users to prevent heroin overdose death: a pilot intervention study. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2):303–311. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f174. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4688551&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Accessed April 21, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bird SM, McAuley A, Perry S, Hunter C. Effectiveness of Scotland’s National Naloxone Programme for reducing opioid-related deaths: a before (2006-10) versus after (2011-13) comparison. Addiction. 2016;111(5):883–891. doi: 10.1111/add.13265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paone D, Heller D, Olson C, Kerker B. Illicit Drug Use in New York City. 2010;9 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maxwell S, Bigg D, Stanczykiewicz K, Carlberg-Racich S. Prescribing Naloxone to Actively Injecting Heroin Users: A Program to Reduce Heroin Overdose Deaths. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(3):89–96. doi: 10.1300/J069v25n03_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett AS, Bell A, Tomedi L, Hulsey EG, Kral AH. Characteristics of an Overdose Prevention, Response, and Naloxone Distribution Program in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. J Urban Heal. 2011;88(6):1020–1030. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9600-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enteen L, Bauer J, McLean R, et al. Overdose prevention and naloxone prescription for opioid users in San Francisco. J Urban Health. 2010;87(6):931–941. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9495-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart A. Annual Report Fiscal Year 2009–2010. San Francisco, CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart A. Annual Report July 2002 to June 2003. San Francisco, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Policy Surveillance Project. Law Atlas. lawatlas.org/datasets/laws-regulating-administration-of-naloxone. Published 2017. Accessed October 21, 2017.

- 15.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Reports. 2016;65(1):1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1er. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behar E, Rowe C, Santos G-M, Coffa D, Santos N, Coffin PO. Acceptability of Naloxone Co-Prescription Among Primary Care Providers Treating Patients on Long-Term Opioid Therapy for Pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):313. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3947-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behar E, Rowe C, Santos G-MG-M, Murphy S, Coffin POPO. Primary Care Patient Experience with Naloxone Prescription. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(5) doi: 10.1370/afm.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beletsky L, Ruthazer R, Macalino G, Rich J, Tan L, Burris S. Physicians’ knowledge of and willingness to prescribe naloxone to reverse accidental opiate overdose: challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2007;84(1):126–136. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9120-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Binswanger IA, Koester S, Mueller SR, Gardner EM, Goddard K, Glanz JM. Overdose Education and Naloxone for Patients Prescribed Opioids in Primary Care: A Qualitative Study of Primary Care Staff. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1837–1844. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3394-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coffin PO, Fuller C, Vadnai L, Blaney S, Galea S, Vlahov D. Preliminary Evidence of Health Care Provider Support for Naloxone Prescription as Overdose Fatality Prevention Strategy in New York City. J Urban Heal Bull New York Acad Med. 2003;80(2):288–290. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatewood AK, Van Wert MJ, Andrada AP, Surkan PJ. Academic physicians’ and medical students’ perceived barriers toward bystander administered naloxone as an overdose prevention strategy. Addict Behav. 2016;61:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green TC, Bowman SE, Zaller ND, Ray M, Case P, Heimer R. Barriers to Medical Provider Support for Prescription Naloxone As Overdose Antidote for Lay Responders. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48(7):558–567. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.787099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mueller SR, Koester S, Glanz JM, Gardner EM, Binswanger IA. Attitudes Toward Naloxone Prescribing in Clinical Settings: A Qualitative Study of Patients Prescribed High Dose Opioids for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):312. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3941-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson JD, Spicyn N, Matson P, Alvanzo AF. Internal Medicine Resident Knowledge, Attitudes and Barriers to Naloxone Prescription in Hospital and Clinic Settings. Subst Abus. 2016 doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1142921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winograd RP, Davis CS, Niculete M, Oliva E, Martielli RP. Medical providers’ knowledge and concerns about opioid overdose education and take-home naloxone rescue kits within Veterans Affairs health care medical treatment settings. Subst Abus. 2017;38(2):135–140. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2017.1303424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behar E, Rowe C, Santos GM, Santos N, Coffin PO. Academic Detailing Pilot for Naloxone Prescribing Among Primary Care Providers in San Francisco. Fam Med. 2017;49(2):122–126. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28218937. Accessed July 27, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coffin PO, Behar E, Rowe C, et al. Nonrandomized intervention study of naloxone coprescription for primary care patients receiving long- Term opioid therapy for pain. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(4):245–252. doi: 10.7326/M15-2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devries J, Rafie S, Polston G. Implementing an overdose education and naloxone distribution program in a health system. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2017;57(2S):S154–S160. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliva EM, Christopher MLD, Wells D, et al. Opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution: Development of the Veterans Health Administration’s national program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2017;57(2):S168–S179.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeda MY, Katzman JG, Dole E, et al. Co-prescription of naloxone as a Universal Precautions model for patients on chronic opioid therapy—Observational study. Subst Abus. 2016;37(4):591–596. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1179704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson CG, Rodriguez F, Carrington AC, Fagan EB. Development of a targeted naloxone coprescribing program in a primary care practice. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2017;57(2):S130–S134. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2016.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han JK, Hill LG, Koenig ME, Das N. Naloxone Counseling for Harm Reduction and Patient Engagement. Fam Med. 2017;49(9):730–733. http://www.stfm.org/FamilyMedicine/Vol49Issue9/Han730. Accessed October 20, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coffin PO, Behar E, Rowe C, et al. Non-randomized intervention study of naloxone co-prescription for primary care patients on longterm opioid therapy for pain. Ann Intern Med. 2016 doi: 10.7326/M15-2771. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darke S, Williamson A, Ross J, Teesson M. Non-fatal heroin overdose, treatment exposure and client characteristics: Findings from the Australian treatment outcome study (ATOS) Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24(5):425–432. doi: 10.1080/09595230500286005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coffin PO, Tracy M, Bucciarelli A, Ompad D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Identifying injection drug users at risk of nonfatal overdose. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(7):616–623. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, Stern MF. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):592–600. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ochoa KC, Davidson P, Evans JL, Hahn J, Page-Shafer K, Moss AR. Heroin overdose among young injection drug users in San Francisco. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80(3):297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jenkins LM, Banta-Green CJ, Maynard C, et al. Risk factors for nonfatal overdose at Seattle-area syringe exchanges. J Urban Heal. 2011;88(1):118–128. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9525-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun E, Dixit A, Humphreys K, Darnall B, Baker L, Mackey S. Association between concurrent use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines and overdose: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2017;356:j760. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webster LR, Cochella S, Dasgupta N, et al. An Analysis of the Root Causes for Opioid-Related Overdose Deaths in the United States. Pain Med. 2011;12(2):S26–S35. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edlund M, Steffick D, Hudson T, Harris K, Sullivan M. Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2007;129(3):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting Aberrant Behaviors in Opioid-Treated Patients: Preliminary Validation of the Opioid Risk Tool. Pain Med. 2005;6(6):432–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association Between Opioid Prescribing Patterns and Opioid Overdose-Related Deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(12):1315–1321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.