Abstract

Recent developments in genome engineering methods have advanced our knowledge of central nervous system (CNS) function in both normal health and following disease or injury. This review discusses current literature using gene editing tools in CNS disease and injury research, such as improving viral-mediated targeting of cell populations, generating new methods for genome editing, reprogramming cells into CNS cell types, and using organoids as models of development and disease. Readers may gain inspiration for continuing research into new genome engineering methods and for therapies for CNS applications.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Investigation of CNS disease and injury has been improved through recent developments in genome editing techniques, enabling studies into causation and possible therapies for neurological disorders [1–3]. Genome engineering often utilizes viral methods, such as adeno-associated virus (AAV), to transduce cell genomes. Additionally, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 systems have become more commonplace in genome editing for both gene knock-in and knock-out. Although these methods are effective, their limitations, e.g potential safety concerns for clinical applications, have inspired a continued search to develop alternative editing methods. For more information on CNS gene delivery methods, readers are referred to a recent review [1]. Our review aims to impart findings from research completed over the past couple of years applying genome editing to CNS disease and injury, including development of tools, models, and methods and the use of reprogrammed cells and 3D culture of CNS tissues.

Tools for CNS genome engineering

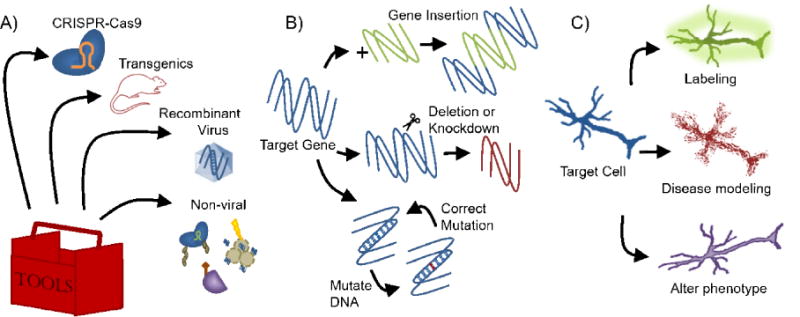

Research tools have been developed to target specific cell populations or create relevant disease models of CNS disease and injury. Gene altering tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 for genome editing can be introduced to cells or into animal models, including transgenic lines, through viral or non-viral means to modify genes in cells or regions of interest (see Figure 1). Isolating a specific cell type enables investigators to determine its role and/or modulate its response to disease or injury, and, importantly, targeting a gene in a specific CNS region or cell population can provide efficacy while reducing any undesirable effects on other tissues. CRISPR-Cas9 systems could cause off-target gene modifications resulting in phenotypic changes, which could affect interpretation of research results or be counterproductive to intended therapies. Additionally, it is plausible that Cas9 – derived from bacteria that cause infections in humans - leads to an immune response in humans[4], which would need to be somehow overcome or require patient screening before being used for gene delivery. These concerns must be addressed before using these tools in patients. Nonetheless, creating these model systems enables the study of a cell population, treatment, or effects of an altered gene in a simplified system while contributing to our knowledge of potential means to improving clinical outcomes.

Figure 1. Genome engineering tools, modifying genes, and modified target cell populations.

A) A genome engineering toolbox should include a method, viral or non-viral, of introducing the target gene modifier, such as CRISPR-Cas9, into cells or transgenic animal models. Recombinant viruses like adeno-associated virus and rabies virus are commonly used to introduce genes to target cells. Non-viral methods include fusing a Cas9 complex with nuclear localization sequences, electroporation, and cell penetrating peptides. B) Genetic modifications include knock-in or insertion of a gene into the target gene, deletion or knockdown of the target gene, introducing a disease-associated mutation into a wildtype target gene, or correcting a disease-associated mutation. C) Target cells can be genetically modified to add reporters to label the target population, to introduce disease-associated proteins or mutations to study the disease, or to observe phenotypic changes that occur with alterations in genotype to find potential therapeutic target genes.

Viral methods for CNS genome engineering

Investigators can use viral-mediated gene expression, lenti- or AAV-based, driven by tissue- or region-specific promoters to modify target cell genomes. Although lentivirus is commonly used in CNS gene delivery, this review will focus on AAV-based methods due to their relatively greater frequency of use and the number of advancements in AAV design for use in CNS in recent publications (please see review on recent use of both methods in brain:[1]). Different AAV serotypes have varying tropisms – or cell types they infect - and thus the route of administration, whether local or systemic, should be considered to better target CNS cells and reduce exposure to off-target tissues. Serotypes AAV1, AAV2, AAV4, AAV5, AAV8, and AAV9 are used in CNS, with AAV9 considered the gold standard because of its ability to transduce neurons and cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [1,5,6]. One study showed that intracisternal or intralumbar administration of AAV9 results in gene expression in brain and cervical spinal cord or throughout CNS, respectively [7]. To improve the utility of AAVs in the CNS, investigators can alter certain characteristics, such as tropism or transduction efficiency, as well as choose promoters with different strengths or tissue-specificity. One group developed AAV variants, including AAV-PHP.B, with at least 40-fold increased gene transfer in various CNS regions compared to AAV9 [5]. This tool can be used to enhance AAV-mediated expression, especially in studies using relatively weak promoters; to illustrate, Jackson et al. targeted neurons by using the weak but neuron-specific human synapsin (hSyn) promoter with AAV-PHP.B, which bolstered gene expression efficiency of a disease-associated protein, allowing them to develop an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) rat model [8]. By combining this tool with promoters for different CNS tissues or anatomical regions, investigators can now more efficiently edit various cell populations.

In addition to improving AAV efficiency, investigators can enhance tissue-specificity for CNS studies. Even when administered locally to the CNS, AAV9 is known to have systemic leakage which results in gene transfer in off-target tissue such as liver. A chimera of AAV2 and AAV9, AAV2g9, was found to have similar efficiency as AAV9 but improved neural tropism, decreased glial tropism, and reduced gene transfer in off-target organs when driven by the hSyn promoter and administered into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), helping overcome the previous drawback of systemic leakage [6]. To evolve AAV variants for increased retrograde transfer of viral particles, Tervo et al. used a relatively weak promoter in neurons, cytomegalovirus (CMV), to drive reporter expression and chose variants that were able to label upstream cells [9]. They isolated the rAAV2-retro variant and used the hSyn promoter for specific, efficient retrograde transport in neurons across synapses, providing an enhanced tool to interrogate neural circuits and permitting access to upstream target cells for editing and manipulation. Another group examined anterograde transneuronal spread of different AAVs and found AAV1 driven by hSyn and CMV (a strong, constitutive mammalian promoter) and AAV9 driven by CMV showed anterograde transsynaptic spread, providing a means for mapping of axonal outputs [10].

Engineered rabies virus (RV), which traditionally in CNS is used for retrograde multisynaptic labeling, was recently modified for monosynaptic labeling of neurons by deleting a glycoprotein (G) necessary for transsynaptic spread (known as RVdG). By AAV-based introduction of RVdG and G to the target neuron, RVdG only has G available in the target cell, thus halting spread after one synaptic jump. This is used as a tool for determining direct, presynaptic connections for neuron targets to better identify inputs and outputs in neuronal circuits. While powerful for circuit interrogation, this system is inefficient and produces toxicity in long-term infections, but researchers are working to overcome these issues. One group identified a strain of RV with ~20-fold increased transsynaptic transfer relative to the current standard with lower neurotoxicity [11], while another group modified G and identified variants with improved RV packaging and a 20-fold increase in presynapse uptake efficiency [12]. These improvements will allow investigators a more complete view of neuronal circuitry.

Intersectional approaches have used viral-based gene delivery with transgenic mouse lines to target specific cell populations. AAV1-Cre was introduced to a Cre-dependent reporter mouse line for cell-specific anterograde labeling, which can be used to identify circuit components or associate observed behaviors by activating labeled, upstream cells [10]. Madisen et al. developed several new mouse lines and AAVs for intersectional targeting of various cells [13]. Their toolbox includes means of fluorescent labeling; inserting voltage, glutamate, and calcium indicators as function sensors; optogenetic activation and silencing, which uses channelrhodopsins (ChR) - light-sensitive membrane channels - to excite or inhibit ChR-expressing neurons; transcriptional activation of the gene of interest; and recombination in specific cell types. They have contributed an array of tools which can be used in combination and with already existing tools to further improve CNS research.

Non-viral methods for CNS genome engineering

Safety concerns, including toxicity and immune response, when using viral-based gene delivery in a clinical setting have inspired research into alternative delivery methods. A cell penetrating peptide that traverses BBB derived from rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) was used to deliver Cre recombinase in reporter mice for targeted somatic genome editing in adult animals [14]. This affords a non-viral approach for animal models, but for more clinical applications, rather than Cre, RVG peptide could be used to deliver therapeutic proteins and nanoparticles or gene editing tools like plasmids or siRNA. Although generally considered safer, non-viral approaches often suffer from poor editing efficiency. One group developed a Cas9-ribonucleoprotein complex engineered to contain multiple nuclear localization sequences (NLS) derived from Simian vacuolating virus 40 (SV40) that, when delivered locally, improved editing efficiency tenfold; however, the complex requires further study to better determine its immunogenicity [15]. In utero electroporation of mouse embryos was used to introduce CRISPR-Cas9 for homology directed repair (HDR) for targeted gene knock-in in neural progenitors [16,17], allowing tagging of proteins, which were then localized or tracked to determine protein dynamics [16]. The same approach could be used for targeted gene knockout to analyze gene contribution to disease, for example. While non-viral methods have been developed with the aim of generating more clinically applicable gene delivery methods, many of them still require further validation regarding efficiencies, immune response, and sustained gene expression.

Deriving CNS cell types and tissues

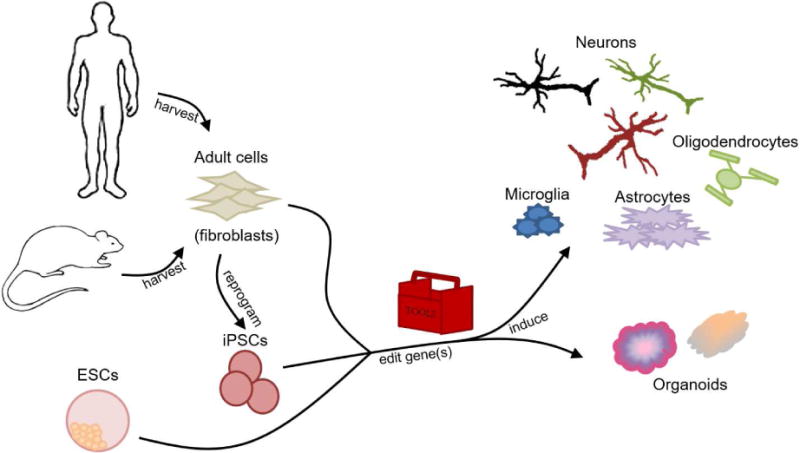

Inducing and reprogramming cells

Directing or redirecting cell fates is an advantageous method of producing human cells for CNS-related studies considering the difficulties of obtaining sufficient numbers of patient cells. Pluripotent cells can be directed toward different CNS lineages, and by using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), investigators can obtain a renewable source of human cells to derive CNS cell types which would otherwise be impossible or require invasive methods to obtain. However, it takes a long time to reprogram the cells to pluripotency, and they could acquire genetic abnormalities in the process, reducing their usefulness. Alternatively, investigators can redirect cell fates by directly reprogramming cells obtained through relatively noninvasive means into CNS cell types. The process of direct reprogramming is quicker but has a lower rate of conversion and induced CNS types have not been well characterized to compare them to native populations [18]. Inducing pluripotent cells and directly reprogramming cells have both been used to examine CNS development and function as well as various cell populations’ involvement in disease (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Reprogramming and inducing cells into CNS cell types and organoids.

Adult cells from humans or animals can be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) or directly into the various CNS cell types or CNS organoid models. The pluripotent cells (iPSCs or embryonic stem cells – ESCs) can be induced into the CNS cells or organoids. During this process, the induced cells can be genetically modified with tools (discussed in the previous section “Tools for genome engineering”) to enable induction toward specific lineages through exposure to transcription factors or to allow study of CNS development, disease, or potential treatments.

Investigators have developed methods of inducing pluripotent cells into different CNS cell types as well as reprogramming adult cells, commonly fibroblasts, toward CNS lineages. While human forebrain inhibitory interneurons had previously been induced from ESCs and iPSCs, directly reprogramming fibroblasts into these interneurons by lentiviral-based expression of five transcription factors (TFs) offers a quicker, efficient method of obtaining cells which are useful for studies investigating epilepsy, pain, motor-impairment disorders, or other diseases involving an imbalance of excitatory versus inhibitory neurons [19]. The Yoo group used lentiviral-based microRNA expression to convert human fibroblasts into medium spiny neurons (MSNs) [20] and motor neurons (MNs) [21]. They found microRNAs generated a permissive chromatin environment, allowing introduction of cell type-specific TFs to induce MNs and MSNs this approach can be used for various neuronal populations that have not yet been derived from fibroblasts. Three groups also used human cells to generate microglial-like cells; they used Sendai virus or lentivirus to reprogram fibroblasts or blood cells to iPSCs before inducing them into microglia-like cells [22–24]. Microglia are innate CNS immune cells which aid in circuit refinement, maintaining homeostasis by clearing debris, neurogenesis, and immune activity; they had not previously been derived from pluripotent cells, so with these induction protocols available, investigators can now better study their development and role in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. All these tools provide cell sources, including patient-specific cells, to allow studies into drug-screening, associating disease genotypes and phenotypes, and possible cell therapies, among other uses.

One issue with using iPSCs to induce CNS cell types is low induction efficiencies and heterogeneity of the resultant cultures. However, CRISPR-Cas9 systems can be used to generate selectable or reporter cell lines, which are useful to isolate target cell types. Selectable cell lines enable researchers to enrich for the cell type of interest, removing unwanted or proliferative cell types that dilute the cells of interest – especially post-mitotic neurons. Selection also removes remaining pluripotent cells which could potentially cause teratoma formation if transplanted. Reporter lines allow identification of the target population through reporter expression or enrichment by fluorescence activated cell sorting. CRISPR-Cas9 can be harnessed to generate a double-stranded DNA break, which, in the presence of donor DNA template containing a selectable or reporter gene, would correct the break by homology directed repair (HDR) and result in insertion of the selectable/reporter gene (see this review [2] for more details). For example, our lab edited mouse ESCs by inserting a gene for an enzyme against puromycin antibiotic into marker genes for spinal interneurons [25,26]. Induced interneurons expressing the marker gene express the enzyme, which allows enrichment of these populations in the presence of puromycin. Additionally, inducible selectable/reporter cell lines could be achieved in a similar way to permit more control over expression of the reporter or selectable marker using donor DNA containing recombination sites or tetracyclin response elements (TRE, see [27] for more information).

3D in vitro culture of CNS tissues

Organoids, which are self-organized 3D in vitro cultures resembling simplified organs, are used as models to examine development of systems and tools for drug screening and study of disease. Culturing pluripotent cells such as iPSCs in suspension allows formation of organoids with regional architecture similar to native developing CNS. An organoid model of midbrain was recently developed to enable study of midbrain development and function of dopaminergic neurons [28]. These organoids could potentially be used to study neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease (PD). Cortical organoids can be grown to study cortical development, as the suspension cultures formed laminated structures containing astrocytes in addition to superficial and deep neurons [29], as well as disease studies such as exposure to Zika virus, allowing controlled, ethical study of a recent major health concern [30]. Organoids derived from human iPSCs from either normal or diseased patients can be used to study neurodegenerative diseases. Organoids from Alzheimer’s disease patients were used to study disease phenotypes [31] and for drug efficacy screening in patient-specific tissues [32]. Normal iPSCs can be genetically modified to introduce mutations or disease-associated proteins before inducing organoids. Alternatively, disease patient-derived organoids can be studied to investigate disease progression and effects on tissue morphology and function. Patient-derived iPSCs can also be edited to correct disease causing genes as an isogenic control sample. For example, iPSCs from frontotemporal dementia patients were either unmodified or edited to restrict formation of a disease-associated protein to study its effect in cerebral organoids [33]. Thus, genome engineering of patient-derived iPSCs used in organoid models assists investigators in study of CNS disease and potential treatment.

Genome editing for CNS cell population analysis

Investigators can use genome editing techniques to develop new methods or approaches for CNS cell characterization or to determine disease-contributing genes. CRISPR-Cas9 was used to screen neuronal outgrowth genes by editing candidate genes and then rapidly imaging phenotypic changes in edited neurons [34]. This approach could also allow identification of genes that inhibit outgrowth, and could be targeted to improve regeneration after injury, for example. Using an intersectional approach, investigators developed a viral-based translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP) assay for molecular profiling of CNS cell populations [35]. They used Cre-dependent AAV-EGFP tagged ribosomal protein in reporter mice to tag and purify translating mRNAs, and by spatiotemporal control of Cre expression, they could target various cell types. This tool is powerful for analyzing both native populations as well as cell types derived from pluripotent cells in vitro, enabling molecular comparison to their native counterparts. As a strategy to determine PD-associated gene risk variants, Soldner et al. combined the editing capability of CRISPR-Cas9 with information on genetic variations and corresponding phenotypes available from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [36]. This approach could also be applied to other neurodegenerative diseases of interest and help identify potential therapeutic gene targets.

Conclusions

This review describes recent studies applying genome engineering in CNS disease and injury. Investigators have developed AAVs for improved gene expression efficiency and target specificity as well as non-viral approaches as safer alternatives. Several cell types and organoid models have been derived from pluripotent cells, including patient-specific iPSCs, enhancing our ability to study CNS development, disease, and potential treatments. Researchers have even developed new methods of profiling different CNS cell populations. While current tools, models, and treatments are imperative to research and to the lives of patients with CNS injuries and diseases, the search to improve treatments continues by investigating new methods and developing tools to use in the lab and the clinic.

Highlights.

Current literature on genome engineering for central nervous system disease and injury is reviewed

Genome editing can generate research tools for isolating specific tissue regions or cell types and models to study function, development, and disease

Reprogrammed cells are a valuable source of renewable, potentially patient-specific, cells for studies into central nervous system disease and function

Genetically modified nervous tissue cells and organoids can be used as model systems to investigate potential therapies for central nervous system disease and injury

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01NS090617 and F31NS100432].

Thank you to my colleagues – Ze Zhong Wang and Nick White - and family - Saiid Nikouee, Sara Nikouee, Theresa Nikouee, and Daan Pardieck - for assisting with proofreading and editing this document. [J.P.]

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Joshi CR, Labhasetwar V, Ghorpade A. Destination Brain: the Past, Present, and Future of Therapeutic Gene Delivery. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2017;12:51–83. doi: 10.1007/s11481-016-9724-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salsman J, Dellaire G. Precision genome editing in the CRISPR era. Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;95:187–201. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2016-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haggarty SJ, Silva MC, Cross A, Brandon NJ, Perlis RH. Advancing drug discovery for neuropsychiatric disorders using patient-specific stem cell models. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2016;73:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charlesworth CT, Deshpande PS, Dever DP, Dejene B, Gomez-Ospina N, Mantri S, Pavel-Dinu M, Camarena J, Weinberg KI, Porteus MH. Identification of Pre-Existing Adaptive Immunity to Cas9 Proteins in Humans. bioRxiv. 2018 doi: 10.1101/243345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deverman BE, Pravdo PL, Simpson BP, Kumar SR, Chan KY, Banerjee A, Wu WL, Yang B, Huber N, Pasca SP, et al. Cre-dependent selection yields AAV variants for widespread gene transfer to the adult brain. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:204–209. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murlidharan G, Sakamoto K, Rao L, Corriher T, Wang D, Gao G, Sullivan P, Asokan A. CNS-restricted Transduction and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Gene Deletion with an Engineered AAV Vector. Mol Ther - Nucleic Acids. 2016;5:e338. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2016.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bey K, Ciron C, Dubreil L, Deniaud J, Ledevin M, Cristini J, Blouin V, Aubourg P, Colle M-A. Efficient CNS targeting in adult mice by intrathecal infusion of single-stranded AAV9-GFP for gene therapy of neurological disorders. Gene Ther. 2017;24:325–332. doi: 10.1038/gt.2017.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson KL, Dayton RD, Deverman BE, Klein RL. Better Targeting, Better Efficiency for Wide-Scale Neuronal Transduction with the Synapsin Promoter and AAV-PHP.B. Front Mol Neurosci. 2016;9:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9*.Tervo DGR, Hwang BY, Viswanathan S, Gaj T, Lavzin M, Ritola KD, Lindo S, Michael S, Kuleshova E, Ojala D, et al. A Designer AAV Variant Permits Efficient Retrograde Access to Projection Neurons. Neuron. 2016;92:372–382. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.021. The authors develop a highly efficient AAV variant for retrograde transport to projection neurons. This provides a non-toxic, efficient option besides rabies virus for retrograde transport. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zingg B, Chou XL, Zhang Z, Mesik L, Liang F, Tao HW, Zhang LI. AAV-Mediated Anterograde Transsynaptic Tagging: Mapping Corticocollicular Input-Defined Neural Pathways for Defense Behaviors. Neuron. 2017;93:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reardon TR, Murray AJ, Turi GF, Wirblich C, Croce KR, Schnell MJ, Jessell TM, Losonczy A. Rabies Virus CVS-N2cδG Strain Enhances Retrograde Synaptic Transfer and Neuronal Viability. Neuron. 2016;89:711–724. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim EJ, Jacobs MW, Ito-Cole T, Callaway EM. Improved Monosynaptic Neural Circuit Tracing Using Engineered Rabies Virus Glycoproteins. Cell Rep. 2016;15:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madisen L, Garner AR, Shimaoka D, Chuong AS, Klapoetke NC, Li L, van der Bourg A, Niino Y, Egolf L, Monetti C, et al. Transgenic mice for intersectional targeting of neural sensors and effectors with high specificity and performance. Neuron. 2015;85:942–958. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou Z, Sun Z, Li P, Feng T, Wu S. Cre fused with RVG peptide mediates targeted genome editing in mouse brain cells in vivo. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1–6. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Staahl BT, Benekareddy M, Coulon-Bainier C, Banfal AA, Floor SN, Sabo JK, Urnes C, Munares GA, Ghosh A, Doudna JA. Efficient genome editing in the mouse brain by local delivery of engineered Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:431–434. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikuni T, Nishiyama J, Sun Y, Kamasawa N, Yasuda R. High-Throughput, High-Resolution Mapping of Protein Localization in Mammalian Brain by in Vivo Genome Editing. Cell. 2016;165:1803–1817. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsunekawa Y, Terhune RK, Fujita I, Shitamukai A, Suetsugu T, Matsuzaki F. Developing a de novo targeted knock-in method based on in utero electroporation into the mammalian brain. Development. 2016;143:3216–3222. doi: 10.1242/dev.136325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broccoli V. Reprogramming of somatic cells: IPS and iN cells. Elsevier B.V; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colasante G, Lignani G, Rubio A, Medrihan L, Yekhlef L, Sessa A, Massimino L, Giannelli SG, Sacchetti S, Caiazzo M, et al. Rapid Conversion of Fibroblasts into Functional Forebrain GABAergic Interneurons by Direct Genetic Reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:719–734. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richner M, Victor MB, Liu Y, Abernathy D, Yoo AS. MicroRNA-based conversion of human fibroblasts into striatal medium spiny neurons. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:1543–1555. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21**.Abernathy DG, Kim WK, McCoy MJ, Lake AM, Ouwenga R, Lee SW, Xing X, Li D, Lee HJ, Heuckeroth RO, et al. MicroRNAs Induce a Permissive Chromatin Environment that Enables Neuronal Subtype-Specific Reprogramming of Adult Human Fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:332–348.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.08.002. The authors show adult human fibroblasts can be reprogrammed to a default neuronal state through exposure to miR-9/9* and miR-124 due to chromatin reconfigurations, allowing transcription factors access to their subtype-specific loci for reprogramming. This provides a means of generating several classes of neurons with known transcription factor markers and can be applied to patient samples. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abud EM, Ramirez RN, Martinez ES, Healy LM, Nguyen CHH, Newman SA, Yeromin AV, Scarfone VM, Marsh SE, Fimbres C, et al. iPSC-Derived Human Microglia-like Cells to Study Neurological Diseases. Neuron. 2017;94:278–293.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23*.Muffat J, Li Y, Yuan B, Mitalipova M, Omer A, Corcoran S, Bakiasi G, Tsai L-H, Aubourg P, Ransohoff RM, et al. Efficient derivation of microglia-like cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Med. 2016;22:1358–1367. doi: 10.1038/nm.4189. The authors provide a protocol with defined culture conditions to generate microglia-like cells from pluripotent cells. This can provide patient-specific sources of cells for further study of a population implicated in neurodegenerative diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandya H, Shen MJ, Ichikawa DM, Sedlock AB, Choi Y, Johnson KR, Kim G, Brown MA, Elkahloun AG, Maric D, et al. Differentiation of human and murine induced pluripotent stem cells to microglia-like cells. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nn.4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu H, Iyer N, Huettner JE, Sakiyama-Elbert SE. A puromycin selectable cell line for the enrichment of mouse embryonic stem cell-derived V3 interneurons. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:220. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0213-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iyer NR, Huettner JE, Butts JC, Brown CR, Sakiyama-Elbert SE. Generation of highly enriched V2a interneurons from mouse embryonic stem cells. Exp Neurol. 2016;277:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das AT, Tenenbaum L, Berkhout B. Tet-On systems for doxycycline-inducible gene expression. Curr Gene Ther. 2016 doi: 10.2174/1566523216666160524144041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jo J, Xiao Y, Sun AX, Cukuroglu E, Tran HD, Göke J, Tan ZY, Saw TY, Tan CP, Lokman H, et al. Midbrain-like Organoids from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells Contain Functional Dopaminergic and Neuromelanin-Producing Neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paşca AM, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, Tian Y, Makinson CD, Huber N, Kim CH, Park J-Y, O’Rourke NA, Nguyen KD, et al. Functional cortical neurons and astrocytes from human pluripotent stem cells in 3D culture. Nat Methods. 2015;12:671–678. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian X, Nguyen HN, Song MM, Hadiono C, Ogden SC, Hammack C, Yao B, Hamersky GR, Jacob F, Zhong C, et al. Brain-Region-Specific Organoids Using Mini-bioreactors for Modeling ZIKV Exposure. Cell. 2016;165:1238–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raja WK, Mungenast AE, Lin Y-T, Ko T, Abdurrob F, Seo J, Tsai L-H. Self-Organizing 3D Human Neural Tissue Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Recapitulate Alzheimer’s Disease Phenotypes. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee H-K, Velazquez Sanchez C, Chen M, Morin PJ, Wells JM, Hanlon EB, Xia W. Three Dimensional Human Neuro-Spheroid Model of Alzheimer’s Disease Based on Differentiated Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seo J, Kritskiy O, Watson LA, Barker SJ, Dey D, Raja WK, Lin Y-T, Ko T, Cho S, Penney J, et al. Inhibition of p25/Cdk5 Attenuates Tauopathy in Mouse and iPSC Models of Frontotemporal Dementia. J Neurosci. 2017;37:9917–9924. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0621-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Callif BL, Maunze B, Krueger NL, Simpson MT, Blackmore MG. The application of CRISPR technology to high content screening in primary neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2017;80:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35*.Nectow AR, Moya MV, Ekstrand MI, Mousa A, McGuire KL, Sferrazza CE, Field BC, Rabinowitz GS, Sawicka K, Liang Y, et al. Rapid Molecular Profiling of Defined Cell Types Using Viral TRAP. Cell Rep. 2017;19:655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.048. The authors use AAV-based tagging of translating proteins as a means of interrogating molecular profiles of different CNS populations. This method can be applied to any population available in a Cre-driver mouse of interest through spatiotemporal controlled application of the AAV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soldner F, Stelzer Y, Shivalila CS, Abraham BJ, Latourelle JC, Barrasa MI, Goldmann J, Myers RH, Young RA, Jaenisch R. Parkinson-associated risk variant in distal enhancer of α-synuclein modulates target gene expression. Nature. 2016;533:95–99. doi: 10.1038/nature17939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]