Abstract

Binge drinking is an increasingly common pattern of risky use associated with numerous health problems, including alcohol use disorders. Because low basal plasma levels of β‐endorphin (β‐E) and an increased β‐E response to alcohol are evident in genetically at‐risk human populations, this peptide is thought to contribute to the susceptibility for disordered drinking. Animal models suggest that the effect of β‐E on consumption may be sex‐dependent. Here, we studied binge‐like EtOH consumption in transgenic mice possessing varying levels of β‐E: wild‐type controls with 100% of the peptide (β‐E +/+), heterozygous mice constitutively modified to possess 50% of wild‐type levels (β‐E +/−) and mice entirely lacking the capacity to synthesize β‐E (−/−). These three genotypes and both sexes were evaluated in a 4‐day, two‐bottle choice, drinking in the dark paradigm with limited access to 20% EtOH. β‐E deficiency determined sexually divergent patterns of drinking in that β‐E −/− female mice drank more than their wild‐type counterparts, an effect not observed in male mice. β‐E −/− female mice also displayed elevated basal anxiety, plasma corticosterone and corticotropin‐releasing hormone mRNA in the extended amygdala, and all of these were normalized by EtOH self‐administration. These data suggest that a heightened risk for excessive EtOH consumption in female mice is related to the drug's ability to ameliorate an overactive anxiety/stress‐like state. Taken together, our study highlights a critical impact of sex on neuropeptide regulation of EtOH consumption.

Keywords: BNST, CeA, CRF, HPA axis, POMC, stress

Introduction

The causes and consequences of drug use differ between men and women, although the mechanisms determining sex‐dependent trajectories remain poorly understood. For example, a longstanding gap between the sexes in alcohol use disorders and their consequences has been shrinking as problematic incidence in women has risen over the past few years (Keyes et al. 2011). One possible contribution to this rise is an increase in female rates of binge drinking, a pattern that predicts negative health outcomes, including alcohol use disorders (Jennison 2004). According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, binge drinking is a pattern of excessive alcohol consumption that results in blood ethanol concentrations (BECs) of 80 mg/dl or above, usually a result of a woman having four, or man having five, drinks within about 2 hours (National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism Advisory Council 2004). Researchers hypothesize that women may be particularly susceptible to negative reinforcing effects of alcohol consumption because they are more prone to stress and anxiety (Lehavot et al. 2014).

The endogenous opioid peptide, β‐endorphin (β‐E), has long been implicated in EtOH consumption (Herz 1997). β‐E, derived from the precursor proopiomelanocortin (POMC), is an agonist with high affinity for μ‐opioid and δ‐opioid receptors (Raffin‐Sanson et al. 2003) where it modulates EtOH reward (Gass & Olive 2007; Roth‐Deri et al. 2008). In the clinic, basal levels of plasma β‐E, as well as a rise in this peptide following alcohol administration, correlate with a heritable risk for high consumption (Dai et al. 2005; Kiefer et al. 2006). Our laboratory and others have demonstrated that β‐E‐deficient mice exhibit altered patterns of EtOH consumption, which depend upon sex (Williams et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2017), and a Pomc haplotype marker has been associated with human alcoholism in women, but not men (Racz et al. 2008). However, the mechanisms responsible for this interaction remain unknown.

β‐Endorphin also regulates hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA‐axis) activity via μ‐opioid mediated inhibition (Buckingham 1986; Wynne & Sarkar 2013), influences basal anxiety‐like behavior and EtOH‐mediated anxiolysis (Grisel et al. 2008; Barfield et al. 2010; Barfield et al. 2013), and interacts with CRH in brain regions associated with stress and anxiety (Reyes et al. 2006; Lam & Gianoulakis 2011). Moreover, CRH signaling in the extended amygdala—comprised the nucleus accumbens shell (NAc), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA)—mediates binge‐like EtOH consumption (Lowery‐Gionta et al. 2012; Pleil et al. 2015; Rinker et al. 2017), and we recently observed increased Crh mRNA in the extended amygdala of β‐E −/− female mice (McGonigle et al. 2016). Therefore, we hypothesized that binge‐like drinking is regulated by sex and β‐E through alterations in Crh expression and glucocorticoid secretion affecting stress circuitry and anxiety‐like behavior.

Methods

Animals

Adult male and female C57BL/6J (β‐E +/+), B6.129S2‐Pomctm1Low/J (stock number: 003191; β‐E −/− mice) and heterozygous (β‐E +/−) mice were either bred in‐house and weaned at 21 days from stock obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) or purchased as adults from Jackson Laboratories, in which case they were acclimated at least 10 days prior to the onset of any experimental procedures. The β‐E‐deficient mice were developed in the laboratory of Malcolm Low and are now fully backcrossed onto a C57BL/6J background. Transgenic mice harbor a truncated Pomc transgene that prevents synthesis of β‐E, although other POMC protein products remain unchanged, such that homozygotes cannot synthesize β‐E and heterozygotes produce ~50% of wild‐type levels (Rubinstein et al. 1996). β‐E −/− male mice have been shown to exhibit an overweight phenotype that increases with age, although we observed no differences in weight across genotypes of either sex in the present study (supplemental results and Fig. S1). The mice were group‐housed by sex and genotype before the start of the experiment, and individually during the experiment, in Plexiglas® cages with corncob bedding and ad libitum access to chow and water. The animal colony and experimental room were maintained at ~21°C with a 12‐hour/12‐hour reverse light/dark cycle (lights off at 0930). All procedures were in accordance with the National Institute of Health guidelines and approved by the Bucknell University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drinking in the dark procedures

A two‐bottle, 4‐day drinking in the dark (DID) procedure was performed (Giardino & Ryabinin 2013) with water continuously available in one bottle for all mice. The mice were acclimated to individual housing for at least 7 days prior to the 4‐day DID testing. On days 1–3 of DID testing, for 2 hours beginning 3 hours into the dark cycle, the mice had access to two 25‐ml graduated cylinders containing either 20% EtOH in tap water (v/v) or tap water alone, while water control groups received tap water in both bottles. On day 4, access to EtOH or the additional water tube was extended to a 4‐hour binge test (BT) session. Sucrose control experiments were performed to assess whether differences in consumption between +/+ and −/− female mice were specific to EtOH. The animals underwent the same DID procedures, except that a 10% sucrose solution (w/v) was presented instead of a 20% EtOH solution. Fluid intake levels were measured by a trained observer blind to experimental condition by reading gradations on bottles with accuracy to the nearest 0.1 ml.

Blood and tissue collection

Immediately following the 4‐hour BT on day 4, the subjects were individually transported to an adjacent room, anesthetized by using isoflurane and rapidly decapitated. Trunk blood was collected and centrifuged to analyze plasma for blood EtOH concentrations (BEC; Analox Alcohol Analyzer, Analox Instruments, Stourbridge, UK) or stored at −20°C for subsequent processing of corticosterone (CORT) by using an ELISA. Simultaneously, the brains were removed, frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C for gene expression by using quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR). Finally, left and right adrenal glands from each mouse were harvested and weighed. To control for potential effects of individual housing stress on CORT, a separate cohort of group‐housed mice was sacrificed at the same time of day to assess homecage CORT.

Post‐DID anxiety‐like behavioral testing

To assess the behavioral effects of voluntary consumption and normalized CORT in β‐E −/− female mice, we evaluated a separate cohort of β‐E +/+ and β‐E −/− female mice for anxiety‐like behavior in the light–dark box (LDB) following the EtOH DID procedure. Immediately following the BT on day 4, the subjects were transported to an adjacent room and placed in a LDB for 5 minutes (Grisel et al. 2008). Experimentally blind observers scored time spent in the light and dark compartments, and crossings between compartments were tallied as a measure of general locomotor activity. Immediately following LDB testing, the animals were anesthetized and rapidly decapitated, and trunk blood was collected for analysis of BECs and CORT as described in the preceding texts.

Brain punch protocol and qRT‐PCR

Frozen tissue was sliced on a Thermo Fisher HM 550 cryostat (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and bilateral 1.5‐mm cylindrical punches were taken of the NAc (AP: +1.94 mm to +0.86 mm; ML: ±0.75 mm; DV: +1.0 mm), BNST (AP: +0.62 mm to −0.22 mm; ML: ±1.0 mm; DV +1.35 mm) and CeA (AP: −0.82 mm to −1.82 mm, ML: ±2.35 mm; DV: +1.25 mm), relative to bregma, and immediately submerged in Qiazol lysis buffer (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Each sample tube containing one brain region from one mouse was homogenized immediately after sectioning. Total RNA was extracted by using the Qiagen RNeasy Lipid Tissue Minikit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Concentration and purity of eluted RNA were verified by using the NanoDrop Lite UV spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and 500 ng of total RNA was reverse‐transcribed by using the iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA) also according to the manufacturer's instructions. qRT‐PCR was performed by using FastStart Essential DNA Probes Master Mix (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PrimeTime® XL qRT‐PCR Assays designed by IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) were performed by using Crh (Assay ID: Mm.PT.58.32061593) and the reference gene, glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (Assay ID: Mm.PT.58.12733669) in duplicate on a LightCycler 96 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). All assays had similar optimum PCR efficiencies. For all qRT‐PCR experiments, glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase gene expression was used as the reference gene and relative changes in gene expression determined by using the 2‐ΔΔCT method (Schmittgen & Livak 2008).

Corticosterone ELISA

Corticosterone was measured by ELISA (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Blood plasma was diluted 1:40 with assay buffer. Absorbance was read at 405 nm by using an iMark microplate reader (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Sample concentrations for CORT were calculated from a standard curve by using graphpad prism version 7.0 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Assay sensitivity was 27 pg/ml with a range of detection up to 20 000 pg/ml. All samples were assayed in duplicate.

Statistical analysis

Repeated measures ANOVAs with sex and genotype as factors were used to analyze EtOH consumption and preference and sucrose consumption (only female mice) across days 1–3 of the DID paradigm. Two‐way ANOVAs with genotype and sex as factors were used to analyze EtOH consumption and preference on the day 4 BT, average EtOH consumption and preference, average weight and homecage CORT. Three‐way ANOVAs with sex, genotype and treatment as factors were used to analyze CORT, adrenal weights and Crh expression in the NAc, BNST and CeA. Simple linear regression was used to analyze relationships between BECs and anxiety‐like behavior. Unpaired two‐tailed t‐tests were used to analyze genotype differences in anxiety‐like behavior and locomotor activity in the LDB and average and BT sucrose consumption. An F‐test for equality of variances was used to compare variances in CORT levels in β‐E −/− female mice based on intoxication threshold. Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to correct for multiple comparisons following significant main effects and interactions. Degrees of freedom may differ between groups/brain regions due to unquantifiable tissue or blood plasma samples. All data were analyzed by using spss 24.0 software and graphpad prism 7.0. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Effects were considered statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

β‐E deficiency promotes enhanced binge‐like EtOH consumption in female, but not male, mice

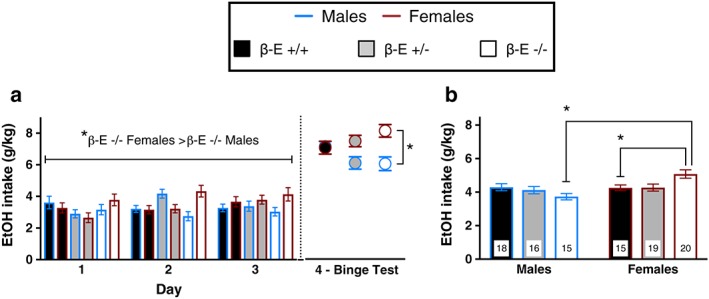

We evaluated male and female β‐E +/+, β‐E +/− and β‐E −/− mice in the DID model of binge drinking to test the hypothesis that β‐E regulates binge‐like EtOH consumption in a sexually dimorphic manner. Binge EtOH consumption across the 2‐hour periods (days 1–3), the 4‐hour BT (day 4) and average consumption are summarized in Fig. 1 (n = 15–20/group). A repeated measures ANOVA on days 1–3 revealed a significant sex by genotype interaction (F (2,97) = 5.648, P = 0.005). All other main effects and interactions were not significant: day (F (2,194) = 1.803, P = 0.167), day by genotype (F (4,194) = 2.197, P = 0.071), day by sex (F (2,194) = 1.724, P = 0.181), day by genotype by sex (F (4,194) = 1.476, P = 0.211), genotype (F (2,97) = 0.426, P = 0.654) and sex (F (1,97) = 2.532, P = 0.115). Post hoc analysis following the sex by genotype interaction indicated that β‐E −/− female mice consumed more EtOH than β‐E −/− male mice across days 1–3 (P < 0.05). A two‐way ANOVA on day 4 BT revealed a main effect of sex (F (1,97) = 12.317, P = 0.001) and a sex by genotype interaction (F (2,97) = 3.853, P = 0.025) but no main effect of genotype (F (2,97) = 0.394, P = 0.675). Post hoc analyses following the sex by genotype interaction indicated that β‐E −/− female mice consumed more EtOH than β‐E −/− male mice during the BT (P < 0.05; Fig. 1a). To determine the overall effect of β‐E on binge‐like EtOH consumption, we analyzed average EtOH consumption across the 4‐day DID paradigm. A two‐way ANOVA revealed a main effect of sex (F (1,97) = 7.631, P = 0.006) and a sex by genotype interaction (F (2,97) = 5.962, P = 0.003) but no main effect of genotype (F (2,97) = 0.476, P = 0.622). Post hoc analyses following the sex by genotype interaction indicated that β‐E −/− female mice consumed more EtOH than β‐E +/+ female mice (P < 0.05) and β‐E −/− male mice (P < 0.05; Fig. 1b). EtOH preference data from these experiments can be found in the supplemental results and Fig. S2. We also conducted sucrose control experiments in a separate cohort of β‐E +/+ and −/− female mice to assess whether differences in consumption were specific to EtOH. These data are presented in the supplemental results and Fig. S4.

Figure 1.

β‐Endorphin (β‐E) masks sex differences in binge‐like EtOH drinking. (a) Daily consumption of 20% EtOH versus water across the 2‐hour sessions (days 1–3) and 4‐hour binge test (day 4) of the drinking in the dark procedure. A repeated measures ANOVA across days 1–3 revealed a significant sex by genotype interaction, and post hoc analysis indicated that β‐E −/− female mice consumed more EtOH than β‐E −/− male mice. A two‐way ANOVA on the day 4 binge test (BT) revealed a main effect of sex (female mice > male mice) and a sex by genotype interaction. There was a main effect of sex and a sex by genotype interaction for the 4‐hour BT. Post hoc analysis indicated that β‐E −/− female mice consumed more EtOH than β‐E −/− male mice. (b) These data are summarized as average consumption across the 4‐day paradigm. There was a main effect of sex (female mice > male mice), and a sex by genotype interaction with post hoc analysis indicating that β‐E −/− female mice consumed more EtOH overall than β‐E +/− and β‐E +/+ female and β‐E −/− male mice. Data are presented as means ± SEM; *P < 0.05 (Bonferroni corrected); n for each group are displayed within their respective bar

Binge‐like EtOH consumption normalizes elevated CORT levels in female, but not male, β‐E −/− mice

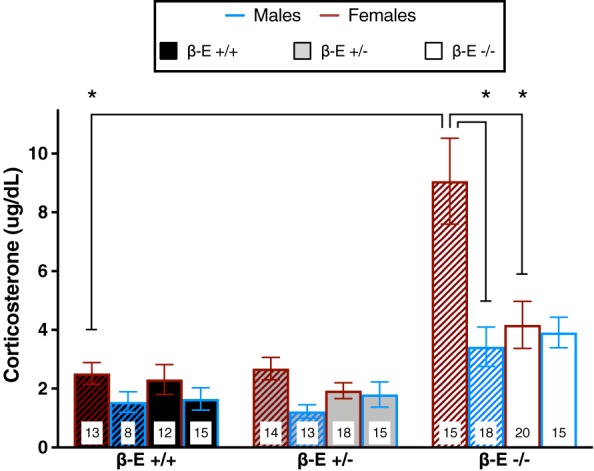

To determine the role of HPA‐axis activity in the sexually divergent pattern of EtOH consumption, we assessed plasma CORT levels immediately following water or EtOH consumption on the day 4 BT. A three‐way ANOVA revealed the main effects of genotype (F (2,159) = 30.688, P < 0.001) and sex (F (1,159) = 14.730, P < 0.001), but not treatment (F (1,159) = 3.854, P = 0.051). There were also significant interactions of genotype by sex (F (2,159) = 3.470, P = 0.033), genotype by treatment (F (2,159) = 3.440, P = 0.034), sex by treatment (F (1,159) = 8.721, P = 0.004) and genotype by sex by treatment (F (2,159) = 3.934, P = 0.022). Post hoc analysis following the three‐way interaction indicated that water control β‐E −/− female mice have higher CORT levels than β‐E +/+ water control female mice (P < 0.05) and water control β‐E −/− male mice (P < 0.05). However, CORT levels are reduced by EtOH drinking in β‐E −/− female mice to levels similar to wild‐type female mice (P > 0.05; Fig. 2). To control for potential effects of individual housing, we also measured CORT levels in a separate cohort of naïve, water‐drinking group‐housed male and female β‐E +/+ and −/− mice (supplemental results and Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

Binge‐like EtOH consumption normalizes corticosterone (CORT) in female, but not male, β‐endorphin (β‐E) −/− mice. Plasma CORT levels obtained immediately following the day 4 binge test from β‐E +/+, +/− and −/− female and male mice consuming either EtOH and water (solid bars) or water controls (hatched bars). A three‐way ANOVA revealed a significant genotype by sex by treatment interaction. Post hoc analysis indicated that β‐E −/− female mice exhibit greater CORT than β‐E +/+ female and β‐E −/− male mice under basal conditions, but voluntary binge‐like EtOH consumption significantly reduces β‐E −/− female CORT levels to near wild‐type levels. Data are presented as means ± SEM; *P < 0.05 (Bonferroni corrected); n for each group are displayed within their respective bar

Anxiolytic effects of EtOH in female mice depend upon β‐E

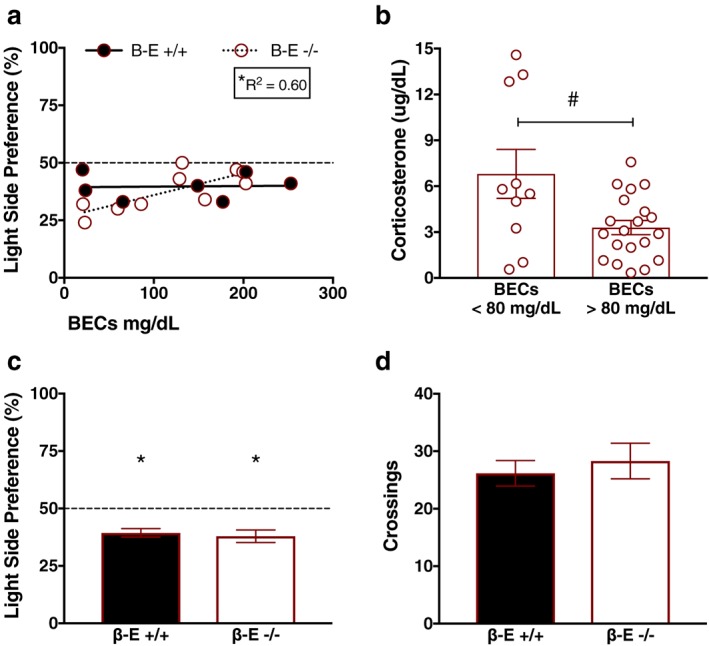

Previous research had demonstrated an inverse relationship between β‐E levels and anxiety‐like behaviors in these lines (Grisel et al. 2008; Barfield et al. 2010; Barfield et al. 2013), but in order to assess the behavioral relevance of the physiological changes in endocrine measures, we tested a separate group containing only female +/+ and −/− mice for anxiety‐like behavior in the LDB after the 4‐day DID procedure. Linear regression revealed a significant relationship between BECs and preference for the light side of a LDB in β‐E −/− female mice (F (1,8) = 12.02, P = 0.0085, R 2 = 0.60), but not β‐E +/+ female mice (F (1,5) = 0.008, P = 0.93), supporting the contention that β‐E −/− female mice exhibit heightened sensitivity to the anxiolytic effects of EtOH (Fig. 3a). One‐sample t‐tests revealed that mean light side preference was significantly less than 50% for both genotypes [β‐E +/+ (t (7) = 5.71, P = 0.0007); β‐E −/− (t (9) = 4.432, P = 0.0016)], and an unpaired t‐test revealed no differences between genotypes (t (16) = 0.423, P = 0.6779), suggesting that both groups exhibited similar anxiety‐like behavior in the LDB on average (Fig. 3c). An unpaired t‐test also indicated that there were no genotype differences in locomotor activity, as assessed by crossings between light/dark compartments (t (15) = 0.5176, P = 0.612; Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

β‐Endorphin (β‐E) −/− female mice exhibit increased sensitivity to EtOH's anxiolytic effects. (a) Linear regressions depicting the relationship between blood ethanol concentrations (BECs) and preference for the light side of the light–dark box (LDB) in β‐E +/+ and −/− female mice immediately following the binge test. There was a significant positive relationship between degree of intoxication (BECs) and reduced anxiety‐like behavior in β‐E −/−, but not β‐E +/+, female mice, suggesting that β‐E −/− female mice exhibited greater EtOH‐mediated anxiolysis. The dashed line represents the value at which equal time is spent in both compartments of the LDB; the asterisk denotes a significant regression and corresponding goodness of fit value. (b) Because the only significant regressions between BECs and corticosterone (CORT) were observed in β‐E −/− female mice (see Results section), we further explored the effect of EtOH consumption on CORT. All β‐E −/− female mice were split into two groups based on intoxication threshold (BECs < 80 mg/dl and BECs > 80 mg/dl), and CORT levels were compared. β‐E −/− female mice that achieved intoxication tended to exhibit reduced CORT, relative to β‐E −/− female mice that did not, although this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.060). However, an F‐test comparing variances indicated that β‐E −/− female mice with BECs >80 mg/dl exhibited significantly reduced variability in CORT levels, relative to β‐E −/− female mice with BECs <80 mg/dl (#P = 0.05). (c) Mean summary of data in (a) indicating that, overall, both β‐E +/+ and −/− exhibited anxiety‐like behavior in the LDB; however, there was no significant difference between genotypes. The asterisk denotes mean light side preference significantly lower than the null hypothesis of 50%. (d) There was also no significant genotype difference in locomotor activity, assessed by crossings, during LDB testing. Data are presented as means ± SEM

To further explore the relationship between binge‐like drinking and CORT, we ran a linear regression that revealed a significant relationship between BECs and CORT solely in β‐E −/− female mice (F (1,29) = 5.721, P = 0.023, R 2 = 0.16; not shown). All other regressions were non‐significant [β‐E −/− male mice (F (1,13) = 1.187, P = 0.295), β‐E +/+ male mice (F (1,12) = 3.04, P = 0.10) and female mice (F (1,17) = 0.568, P = 0.461), and β‐E +/− male mice (F (1,13) = 0.043, P = 0.837) and female mice (F (1,16) = 1.595, P = 0.224)]. We next split β‐E −/− female mice based on level of intoxication, those with BECs <80 or >80 mg/dl, and analyzed CORT as a function of pharmacological intoxication. An unpaired t‐test with Welch's correction revealed a strong trend for reduced CORT only in β‐E −/− female mice that achieved intoxication (t (10.54) = 2.105, P = 0.060), although this did not reach statistical significance. However, an F‐test to compare variances indicated that variance in β‐E −/− female mice achieving intoxicating BECs (mean ± SEM = 3.294±0.463, n = 20) was significantly reduced relative to β‐E −/− female mice that did not achieve intoxication (mean ± SEM = 6.802 ± 1.601, n = 10; F (9,19) = 5.968, P = 0.001), suggesting that intoxicating doses of EtOH serve to reduce the variability of glucocorticoid secretion in β‐E −/− female mice (Fig. 3b).

β‐E −/− mice have elevated BNST Crh expression, which is normalized by binge‐like EtOH consumption

To determine a potential mechanism underlying the enhanced EtOH consumption and elevated CORT levels in β‐E −/− female mice, we used qRT‐PCR to analyze Crh mRNA in the NAc, BNST and CeA in a subset of male and female β‐E +/+, β‐E +/− and β‐E −/− mice from the water and EtOH DID experiments. Our hypothesis was focused on the BNST and CeA, and the NAc was included as a neuroanatomical control region. However, we did observe changes in this forebrain region that were dependent upon sex (supplemental results and Fig. S5).

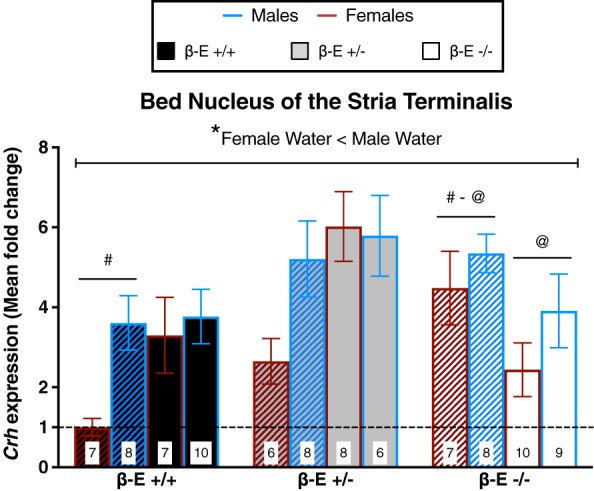

A three‐way ANOVA on BNST Crh revealed significant main effects of genotype (F (2,82) = 7.020, P = 0.002) and sex (F (1,82) = 10.857, P = 0.001), but not treatment (F (1,82) = 0.531, P = 0.468). There was also significant genotype by treatment (F (2,82) = 9.242, P < 0.001) and sex by treatment (F (1,82) = 3.979, P = 0.049) interactions, but not genotype by sex (F (2,82) = 1.226, P = 0.299) or genotype by sex by treatment (F (2,82) = 1.741, P = 0.182). Post hoc analysis following the genotype by treatment interaction indicated that β‐E −/− water controls have higher Crh expression than β‐E +/+ water controls (P < 0.05). However, in EtOH drinking, β‐E −/− mice Crh expression is reduced, relative to β‐E −/− water controls (P < 0.05), to levels similar to β‐E +/+ EtOH drinking mice (P > 0.05), suggesting that β‐E −/− mice exhibit elevated BNST Crh under basal conditions, but binge‐like EtOH drinking normalizes Crh. Post hoc analyses following the sex by treatment interaction indicated that male water controls have higher BNST Crh than female water controls (P < 0.05), suggesting that under basal conditions, female mice have less Crh mRNA in the BNST than male mice (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

β‐Endorphin (β‐E) −/− mice have elevated bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) Crh under basal conditions, but binge‐like ethanol consumption normalizes Crh expression. Crh mRNA expression from mice consuming either EtOH and water (solid bars) or water controls (hatched bars) is represented as mean fold change (±SEM) normalized to β‐E +/+ female water mice as indicated by the dashed line. A three‐way ANOVA revealed a genotype by treatment interaction and a sex by treatment interaction. Post hoc analysis following the genotype by treatment interaction indicated that β‐E −/− water controls exhibit increased Crh expression, relative to β‐E +/+ water controls. However, binge‐like EtOH consumption reduced Crh in β‐E −/−, relative to water controls, such that there was no longer a genotype difference in BNST Crh expression. Note that these effects are primarily driven by differences in female mice; however, the lack of a significant 3‐way interaction precluded our ability to statistically assess such comparisons. Although, post hoc analysis following the sex by treatment interaction indicated that, overall, female water controls have lower BNST Crh mRNA than male water controls (*), which provides novel evidence for basal sex differences in BNST Crh expression. Like symbols indicate significant differences between groups (P < 0.05; Bonferroni corrected); n for each group are displayed within their respective bar

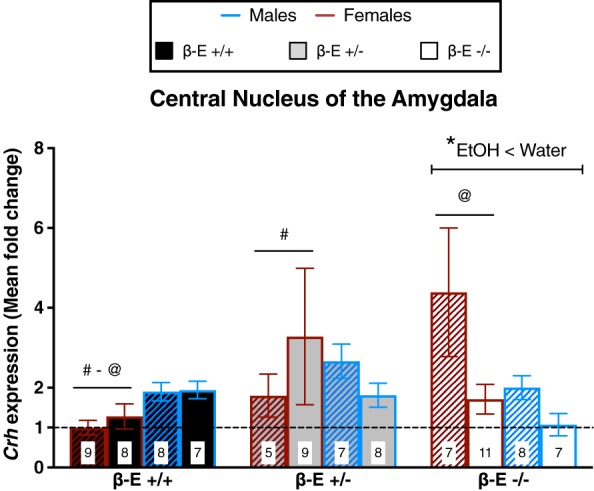

β‐E levels negatively correlate with CeA Crh expression in female, but not male, mice

A three‐way ANOVA on CeA Crh revealed significant genotype by sex (F (2,82) = 4.478, P = 0.014) and genotype by treatment (F (2,82) = 4.577, P = 0.013) interactions. All other main effects and interactions were not significant: genotype (F (2,82) = 3.040, P = 0.053), sex (F (1,82) = 0.287, P = 0.594), treatment (F (1,82) = 2.508, P = 0.117), sex by treatment (F (1,82) = 0.917, P = 0.341) and genotype by sex by treatment (F (2,82) = 1.673, P = 0.194). Post hoc analyses following the genotype by sex interaction indicated that β‐E −/− and β‐E +/− female mice had greater CeA Crh expression than β‐E +/+ female mice (P < 0.05), suggesting that β‐E negatively correlates with CeA Crh in female, but not male, mice. Post hoc analyses following the genotype by treatment interaction indicated that EtOH drinking β‐E −/− mice had lower Crh than β‐E −/− water controls (P < 0.05), suggesting that in β‐E −/− mice, binge‐like EtOH consumption reduces Crh expression in the CeA (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Sex differences in CeA Crh mRNA: β‐Endorphin (β‐E) is inversely associated with CeA Crh in female, but not male, mice. Crh mRNA expression from mice consuming either EtOH and water (solid bars) or water controls (hatched bars) is represented as mean fold change (±SEM) normalized to β‐E +/+ female water mice as indicated by the dashed line. A three‐way ANOVA revealed a genotype by sex interaction and a genotype by treatment interaction. Post hoc analysis following the genotype by sex interaction indicated that β‐E −/− and β‐E +/− female mice exhibit higher CeA Crh than β‐E +/+ female mice; however, these effects were not observed in male mice. Post hoc analysis following the genotype by treatment interaction indicated that binge‐like EtOH consumption reduced Crh only in β‐E −/− mice (*), which was likely driven by the magnitude of reduction in β‐E −/− female mice. Like symbols indicate significant differences between groups (P < 0.05; Bonferroni corrected); n for each group are displayed within their respective bar

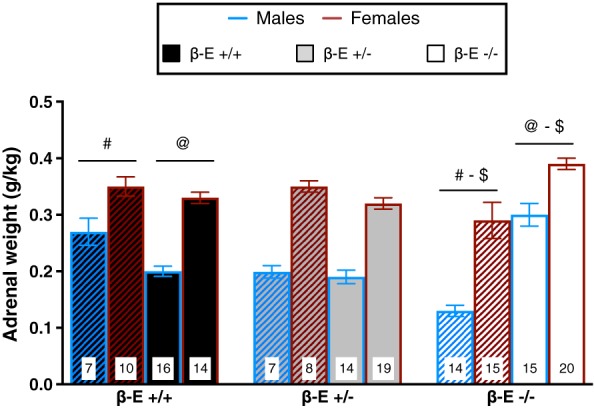

Adrenal glands of β‐E‐deficient mice are more sensitive to EtOH‐induced alterations

We previously observed increased adrenal gland weight in β‐E deficient mice following EtOH exposure (Grisel et al. 2008; McGonigle et al. 2016) but did not explore basal or sex differences. Therefore, immediately following the BT on day 4, the left and right adrenal glands were harvested and total adrenal weight (normalized by body weight, g/kg) was calculated and is summarized in Fig. 6.

Figure 6.

β‐Endorphin (β‐E) −/− mice exhibit heightened sensitivity to EtOH‐induced changes in adrenal gland size. Total adrenal gland weight (mean ± SEM, normalized by body weight) from mice consuming either EtOH and water (solid bars) or water controls (hatched bars). A three‐way ANOVA revealed a main effect of sex, indicating that, overall, female mice have larger adrenals than male mice. There was also a genotype by treatment interaction. Post hoc analysis following the genotype by treatment interaction indicated that β‐E −/− water controls have smaller adrenals than β‐E +/+ water controls. However, binge‐like EtOH consumption increased adrenal size only in β‐E −/− mice, relative to β‐E −/− water controls, which resulted in β‐E −/− EtOH mice possessing larger adrenals than β‐E +/+ EtOH mice. Like symbols indicate significant differences between groups (P < 0.05; Bonferroni corrected); n for each group are displayed within their respective bar

A three‐way ANOVA revealed a main effect of sex (F (1,144) = 103.975, P < 0.001), indicating that female adrenals weighed more than male adrenals, and a significant genotype by treatment interaction (F (2,144) = 21.445, P < 0.001). No other main effects or interactions were significant: genotype (F (2,144) = 1.251, P = 0.289), treatment (F (1,144) = 2.662 P = 0.105), genotype by sex (F (2,144) = 1.112, P = 0.332), sex by treatment (F (1,144) = 0.015, P = 0.902) and genotype by sex by treatment (F (2,144) = 1.712, P = 0.184). Post hoc analysis following the genotype by treatment interaction indicated that water control β‐E −/− mice have smaller adrenals than β‐E +/+ water controls (P < 0.05). However, binge‐like EtOH drinking increases adrenal size in β‐E −/− mice (P < 0.05), such that EtOH drinking β‐E −/− mice exhibit larger adrenals than EtOH drinking β‐E +/+ mice (P < 0.05).

Discussion

We investigated behavioral, neuroendocrine and genetic substrates of EtOH consumption in a binge‐drinking model that reliably produces pharmacological intoxication (Giardino & Ryabinin 2013). Using transgenic mice (Rubinstein et al. 1996), we show that β‐E deficiency results in sexually divergent patterns of EtOH consumption with corresponding alterations in HPA‐axis activity and Crh expression in the extended amygdala.

β‐Endorphin deficiency enhances voluntary binge‐like EtOH consumption in female, but not male, mice. β‐E −/− female mice also exhibit elevated CORT, which is normalized by voluntary EtOH drinking, coincident with a decrease in anxiety‐like behavior. Under basal (i.e. water‐drinking) conditions, β‐E −/− mice exhibit increased BNST Crh expression, and EtOH consumption obviates this difference. Similarly, β‐E levels negatively correlate with CeA Crh expression in female, but not male, mice and the elevated basal expression is normalized following EtOH consumption. β‐E −/− mice also exhibit heightened sensitivity to EtOH‐induced changes in adrenal gland size. These data suggest that genetic and neuroendocrine markers of exaggerated stress sensitivity correlate with binge‐like EtOH drinking, perhaps contributing to sex‐dependent trajectories in alcohol use disorders. We also provide novel evidence for sex differences in Crh expression. That is, female mice have lower basal BNST Crh than male mice, but this difference is abolished following binge‐like EtOH consumption.

Previous research demonstrated that β‐E influences EtOH consumption (Grisel et al. 1999; Racz et al. 2008) and that the peptide's impact may be sex dependent (Williams et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2017). β‐E is synthesized in both hypothalamic and pituitary neurons, but because we used a global knockout, the current study does not delineate the source of influence (Logan et al. 2015). However, Zhou et al. (2017) did not see an effect of pituitary‐specific POMC knockout on drinking in the DID model. Variations in β‐E also influence anxiety‐like behavior sex‐dependently, as β‐E −/− female mice display heightened stress responses relative to other groups (Grisel et al. 2008; Barfield et al. 2010; Barfield et al. 2013). In the present study, we demonstrate that β‐E −/− female mice also exhibit approximately two to threefold increases in plasma CORT and Crh mRNA in the BNST and CeA compared with wild‐type female mice. Because the BNST and CeA regulate stress, anxiety and alcohol‐related behaviors, primarily through CRH signaling (Gilpin et al. 2015; Vranjkovic et al. 2017), these differences are likely to contribute to the high‐drinking, high‐stress phenotype of β‐E −/− female mice. The BNST regulates HPA‐axis activation via excitatory and inhibitory projections to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), and the CeA can modulate these inputs via GABAergic projections to the BNST (Choi et al. 2007). Both CRH and EtOH can increase CeA GABAergic transmission onto inhibitory PVN‐projecting BNST neurons, resulting in disinhibition of PVN CRH neurons and activation of the HPA‐axis (Gilpin 2012). Thus, increased Crh in the CeA and/or BNST of β‐E −/− female mice may explain elevations in basal CORT. While acute EtOH has also been shown to increase adrenal size, the increase in β‐E −/− mice, following only 4 days of EtOH drinking, suggests they exhibit enhanced adrenal sensitivity to EtOH, which might be associated with their dysregulated HPA‐axis activity (Rivier & Vale 1985; Rasmussen et al. 2000).

Elevated CRH in the BNST and CeA are hallmarks of a negative affective state that drives excessive EtOH consumption, presumably to alleviate the associated symptoms (Koob 2013). Toward that end, Olive and colleagues demonstrated that extracellular levels of CRH increase during EtOH withdrawal and that subsequent consumption following reintroduction of EtOH reduced CRH to basal levels (Olive et al. 2002), a pattern observed with CORT levels and Crh mRNA in our β‐E −/− female mice following binge EtOH consumption. Moreover, chemogenetic inhibition of BNST CRH neurons reduces binge‐like EtOH consumption, suggesting a causal role for BNST CRH signaling in regulating excessive drinking (Pleil et al. 2015; Rinker et al. 2017). Similarly, extracellular CRH in the CeA also increases during EtOH withdrawal, and immunoreactivity in the CeA is upregulated following binge‐like EtOH consumption, but blockade of CRH1 receptors in the CeA prevents the excessive EtOH consumption associated with these effects (Funk et al. 2006; Lowery‐Gionta et al. 2012). Taken together, these findings suggest a potential mechanism that puts β‐E −/− female mice at increased risk for binge‐like EtOH consumption.

The tension reduction hypothesis proposes that the motivation to consume alcohol manifests from a desire to reduce stress and anxiety (Cappell & Herman 1972), a clinical phenomenon that is more pronounced in female subjects (Sinha et al. 1998). In addition, rodents displaying heightened anxiety‐like behavior are more susceptible to the anxiolytic effects of EtOH (Stewart et al. 1993; Grisel et al. 2008) and anxiety‐like behavior has been shown to predict high levels of EtOH consumption and preference (Spanagel et al. 1995). The present results suggest that low β‐E confers elevated anxiety‐like behavior and enhanced EtOH‐mediated anxiolysis in female mice, which corresponds with clinical data correlating low plasma β‐E with anxiety and negative affect‐related psychopathologies (Dai et al. 2005; Merenlender‐Wagner et al. 2009).

Similarly, stress also modulates EtOH intake, often leading to increases in consumption and instigating alcohol‐seeking behavior (Spanagel et al. 2014). Stress‐induced EtOH consumption is regulated by glucocorticoids (Ostroumov et al. 2016), suggesting that the elevated glucocorticoid tone in β‐E −/− female mice may contribute to their increased EtOH consumption.

Conclusions

Women experience increased susceptibility for many stress‐related psychiatric disorders, which often co‐occur with alcohol use disorders and exacerbate excessive alcohol use (McLean et al. 2011). Despite formidable evidence that women are more sensitive to stress, alcohol and their interaction (Logrip et al. 2017), the neural mechanisms underlying sex‐specific regulation of alcohol use have been poorly understood. The present findings help fill this gap by demonstrating sexually dimorphic neuropeptide regulation of EtOH sensitivity.

Our data suggest that sex and β‐E interact to determine sexually dimorphic effects on excessive alcohol consumption and tie this tendency to heightened HPA‐axis activity, enhanced EtOH‐mediated anxiolysis and elevated Crh in the BNST and CeA. Given the importance of neuropeptide signaling in EtOH‐related behaviors (Koob 2013), it seems plausible that other neuropeptides also demonstrate distinct sex‐specific effects. Taken together, our observations shed light on the previously unknown impact of sex and β‐E on EtOH consumption and suggest that understanding the trajectory toward disordered drinking may depend on better knowledge of sex‐dependent substrates.

Supporting information

Figure S1. No differences in weight across genotype during the EtOH DID experiments.

Figure S2. β‐E deficiency does not alter EtOH preference.

Figure S3. Elevated basal CORT in β‐E −/− females is present in experimentally naïve mice.

Figure S4. β‐E +/+ and −/− females do not differ in binge‐like sucrose consumption.

Figure S5. Females exhibit lower Crh expression than males, under basal conditions, but increase expression following binge‐like EtOH consumption.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R15 AA022506). The authors would like to thank David Freestone for discussions regarding statistics; Colleen McGonigle for her technical assistance and help with data collection; and Grace Leung, Bernadette Chaney, Kiarah Leonard and Ellie Mack for their assistance with sample collection and data entry. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors Contribution

T.B.N. performed data acquisition. D.E.W. assisted with qRT‐PCR data collection. T.B.N., E.M.R. and J.E.G. designed the study and performed data analysis. T.B.N. and J.E.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed content and approved final version for publication.

Nentwig, T. B. , Wilson, D. E. , Rhinehart, E. M. , and Grisel, J. E. (2019) Sex differences in binge‐like EtOH drinking, corticotropin‐releasing hormone and corticosterone: effects of β‐endorphin. Addiction Biology, 24: 447–457. 10.1111/adb.12610.

References

- Barfield ET, Barry SM, Hodgin HB, Thompson BM, Allen SS, Grisel JE (2010) Beta‐endorphin mediates behavioral despair and the effect of ethanol on the tail suspension test in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34:1066–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barfield ET, Moser VA, Hand A, Grisel JE (2013) β‐endorphin modulates the effect of stress on novelty‐suppressed feeding. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 7:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham JC (1986) Stimulation and inhibition of corticotrophin releasing factor secretion by beta endorphin. Neuroendocrinology 42:148–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappell H, Herman CP (1972) Alcohol and tension reduction. A review. Q J Stud Alcohol 33:33–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D, Furay A, Evanson N, Ostrander M, Ulrich‐Lai Y, Herman J (2007) Bed Nucleus of the stria terminalis subregions differentially regulate hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity: implications for the integration of limbic inputs. J Neurosci 27:2025–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Thavundayil J, Gianoulakis C (2005) Differences in the peripheral levels of beta‐endorphin in response to alcohol and stress as a function of alcohol dependence and family history of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:1965–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk CK, O'Dell LE, Crawford EF, Koob GF (2006) Corticotropin‐releasing factor within the central nucleus of the amygdala mediates enhanced ethanol self‐administration in withdrawn, ethanol‐dependent rats. J Neurosci 26:11 324–11 332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JT, Olive MF (2007) Effects of immunoneutralization of beta‐endorphin in the nucleus accumbens on intravenous ethanol self‐administration in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31:87A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardino WJ, Ryabinin AE (2013) CRF1 receptor signaling regulates food and fluid intake in the drinking‐in‐the‐dark model of binge alcohol consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37:1161–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW (2012) Corticotropin‐releasing factor (CRF) and neuropeptide Y (NPY): effects on inhibitory transmission in central amygdala, and anxiety‐ & alcohol‐related behaviors. Alcohol 46:329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW, Herman MA, Roberto M (2015) The central amygdala as an integrative hub for anxiety and alcohol use disorders. Biol Psychiatry 77:859–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisel JE, Bartels JL, Allen SA, Turgeon VL (2008) Influence of beta‐endorphin on anxious behavior in mice: interaction with EtOH. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 200:105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisel JE, Mogil JS, Grahame NJ, Rubinstein M, Belknap JK, Crabbe JC, Low MJ (1999) Ethanol oral self‐administration is increased in mutant mice with decreased beta‐endorphin expression. Brain Res 835:62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz A (1997) Endogenous opioid systems and alcohol addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 129:99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennison KM (2004) The short‐term effects and unintended long‐term consequences of binge drinking in college: a 10‐year follow‐up study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 30:659–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Li G, Hasin DS (2011) Birth cohort effects and gender differences in alcohol epidemiology: a review and synthesis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35:2101–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer F, Jahn H, Otte C, Nakovics H, Wiedemann K (2006) Effects of treatment with acamprosate on beta‐endorphin plasma concentration in humans with high alcohol preference. Neurosci Lett 404:103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF (2013) Addiction is a reward deficit and stress surfeit disorder. Front Psych 4:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam MP, Gianoulakis C (2011) Effects of acute ethanol on corticotropin‐releasing hormone and β‐endorphin systems at the level of the rat central amygdala. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 218:229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Stappenbeck CA, Luterek JA, Kaysen D, Simpson TL (2014) Gender differences in relationships among PTSD severity, drinking motives, and alcohol use in a comorbid alcohol dependence and PTSD sample. Psychol Addict Behav 28:42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan RW, Wynne O, Maglakelidze G, Zhang C, O'Connell S, Boyadjieva NI, Sarkar DK (2015) β‐Endorphin neuronal transplantation into the hypothalamus alters anxiety‐like behaviors in prenatal alcohol‐exposed rats and alcohol‐non‐preferring and alcohol‐preferring rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39:146–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logrip ML, Oleata C, Roberto M (2017) Sex differences in responses of the basolateral‐central amygdala circuit to alcohol, corticosterone and their interaction. Neuropharmacology 114:123–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery‐Gionta EG, Navarro M, Li C, Pleil KE, Rinker JA, Cox BR, Sprow GM, Kash TL, Thiele TE (2012) Corticotropin releasing factor signaling in the central amygdala is recruited during binge‐like ethanol consumption in C57BL/6J mice. J Neurosci 32:3405–3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonigle CE, Nentwig TB, Wilson DE, Rhinehart EM, Grisel JE (2016) β‐endorphin regulates alcohol consumption induced by exercise restriction in female mice. Alcohol (Fayetteville, NY) 53:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG (2011) Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res 45:1027–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merenlender‐Wagner A, Dikshtein Y, Yadid G (2009) The beta‐endorphin role in stress‐related psychiatric disorders. Curr Drug Targets 10:1096–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institue on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2004) NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsletter 3:3. [Google Scholar]

- Olive MF, Koenig HN, Nannini MA, Hodge CW (2002) Elevated extracellular CRF levels in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis during ethanol withdrawal and reduction by subsequent ethanol intake. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 72:213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroumov A, Thomas AM, Kimmey BA, Karsch JS, Doyon WM, Dani JA (2016) Stress increases ethanol self‐administration via a shift toward excitatory GABA signaling in the ventral tegmental area. Neuron 92:493–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleil KE, Rinker JA, Lowery‐Gionta EG, Mazzone CM, McCall NM, Kendra AM, Olson DP, Lowell BB, Grant KA, Thiele TE, Kash TL (2015) NPY signaling inhibits extended amygdala CRF neurons to suppress binge alcohol drinking. Nat Neurosci 18:545–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racz I, Schürmann B, Karpushova A, Reuter M, Cichon S, Montag C, Fürst R, Schütz C, Franke PE, Strohmaier J, Wienker TF, Terenius L, Osby U, Gunnar A, Maier W, Bilkei‐Gorzó A, Nöthen M, Zimmer A (2008) The opioid peptides enkephalin and beta‐endorphin in alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry 64:989–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffin‐Sanson ML, de Keyzer Y, Bertagna X (2003) Proopiomelanocortin, a polypeptide precursor with multiple functions: from physiology to pathological conditions. Eur J Endocrinol 149:79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen DD, Boldt BM, Bryant CA, Mitton DR, Larsen SA, Wilkinson CW (2000) Chronic daily ethanol and withdrawal: 1. Long‐term changes in the hypothalamo‐pituitary‐adrenal axis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24:1836–1849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BA, Glaser JD, Magtoto R, Van Bockstaele EJ (2006) Pro‐opiomelanocortin colocalizes with corticotropin‐releasing factor in axon terminals of the noradrenergic nucleus locus coeruleus. Eur J Neurosci 23:2067–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinker JA, Marshall SA, Mazzone CM, Lowery‐Gionta EG, Gulati V, Pleil KE, Kash TL, Navarro M, Thiele TE (2017) Extended amygdala to ventral tegmental area corticotropin‐releasing factor circuit controls binge ethanol intake. Biol Psychiatry 81:930–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivier C, Vale W (1985) Effect of the long‐term administration of corticotropin‐releasing factor on the pituitary‐adrenal and pituitary‐gonadal axis in the male rat. J Clin Invest 75:689–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth‐Deri I, Green‐Sadan T, Yadid G (2008) β‐Endorphin and drug‐induced reward and reinforcement. Prog Neurobiol 86:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein M, Mogil JS, Japón M, Chan EC, Allen RG, Low MJ (1996) Absence of opioid stress‐induced analgesia in mice lacking beta‐endorphin by site‐directed mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:3995–4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ (2008) Analyzing real‐time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc 3:1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Robinson J, O'Malley S (1998) Stress response dampening: effects of gender and family history of alcoholism and anxiety disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 137:311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Montkowski A, Allingham K, Stohr T, Shoabib M, Holsboer F, Landgraf R (1995) Anxiety: a potential predictor of vulnerability to the initiation of ethanol self‐administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 122:369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Noori HR, Heilig M (2014) Stress and alcohol interactions: animal studies and clinical significance. Trends Neurosci 37:219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RB, Gatto GJ, Lumeng L, Li TK, Murphy JM (1993) Comparison of alcohol‐preferring (P) and nonpreferring (NP) rats on tests of anxiety and for the anxiolytic effects of ethanol. Alcohol . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vranjkovic O, Pina M, Kash TL, Winder DG (2017) The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in drug‐associated behavior and affect: a circuit‐based perspective. Neuropharmacology 122:100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SB, Holloway A, Karwan K, Allen S, Grisel JE (2007) Oral self‐adminstration of ethanol in transgenic mice lacking B‐endorphin. Impulse Online Journal.

- Wynne O, Sarkar DK (2013) Stress and neuroendocrine‐immune interaction: a therapeutic role for β‐endorphin. Handbook of Psychoneuroimmunology (Kuscnecov A, Anisman H eds): 198‐211.

- Zhou Y, Rubinstein M, Low M, Kreek M (2017) Hypothalamic‐specific proopiomelanocortin deficiency reduces alcohol drinking in male and female mice. Genes Brain Behav 16:499–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. No differences in weight across genotype during the EtOH DID experiments.

Figure S2. β‐E deficiency does not alter EtOH preference.

Figure S3. Elevated basal CORT in β‐E −/− females is present in experimentally naïve mice.

Figure S4. β‐E +/+ and −/− females do not differ in binge‐like sucrose consumption.

Figure S5. Females exhibit lower Crh expression than males, under basal conditions, but increase expression following binge‐like EtOH consumption.