Abstract

We present a theoretical study aiming at model fitting for sensory neurons. Conventional neural network training approaches are not applicable to this problem due to lack of continuous data. Although the stimulus can be considered as a smooth time-dependent variable, the associated response will be a set of neural spike timings (roughly the instants of successive action potential peaks) that have no amplitude information. A recurrent neural network model can be fitted to such a stimulus-response data pair by using the maximum likelihood estimation method where the likelihood function is derived from Poisson statistics of neural spiking. The universal approximation feature of the recurrent dynamical neuron network models allows us to describe excitatory-inhibitory characteristics of an actual sensory neural network with any desired number of neurons. The stimulus data are generated by a phased cosine Fourier series having a fixed amplitude and frequency but a randomly shot phase. Various values of amplitude, stimulus component size, and sample size are applied in order to examine the effect of the stimulus to the identification process. Results are presented in tabular and graphical forms at the end of this text. In addition, to demonstrate the success of this research, a study involving the same model, nominal parameters and stimulus structure, and another study that works on different models are compared to that of this research.

Keywords: Sensory neurons, Recurrent neural network, Excitatory neuron, Inhibitory neuron, Neural spiking, Maximum likelihood estimation

Introduction

General discussion on neurons and information flow

Theoretical or computational neuroscience is a recent field of research that emerged after the development of mathematical models of real biological neurons. The Hodgkin–Huxley model [1], which can be considered as a biological oscillator, was the first sounding attempt in this field. Thereafter, a considerable amount of similar research was conducted and simpler or more complicated models were derived. Most of these involve the membrane potential as the main dynamical variable (Fitzhugh-Nagumo [2], Morris-Lecar [3] models). On the other hand, some others involve different variables. One example that seems to have a crucial position in computational neuroscience is the neural firing rate based model [4], which is actually an extension to the continuous time dynamical recurrent neural network [5, 6]. The efficiency and usability of these models depend on the aim of the research and the limitations set by the simulation/experiment environment. In experiments related to the computational neuroscience field, one such limitation may arise from the measurement capability. In vivo experiments do not allow the real-time measurement of the membrane potential. An attempt to achieve this will likely interrupt the propagation of action potentials due to a change in the axial membrane physical properties at the instant of electrode placement. In some cases, the neuron may be damaged. Thus, a feasibly practical way to gather data in vivo from a live neuron is to record the instants of successive action potentials (in other words the spiking instants) using an electrode attached at a site in the surrounding medium. By doing so, the current flow through the surrounding conductance helps record the spiking times. This is of interest to theoretical or computational neuroscience studies. Recent studies such as [7] suggest that the information transmitted along the sensory and motor neurons is coded somehow by the temporal locations of the spikes and/or the associated firing rates. So the timings of the spikes can be collected by placing an electrode in the surroundings of the studied neuron. Another challenging feature of the neural spiking phenomena is that it is not a deterministic event. The stochasticity of the ion channels [8] and synaptic noise led to the fact that the data transmitted along the neurons are corrupted by noise. Again from related research [9], it can be noted that this stochasticity of neural spiking obeys the famous inhomogeneous Poisson process at least for the sensory neurons. Hence, a proper likelihood methodology may aid parameter identification procedures.

Modeling

Knowing that there are dozens of neuron models in the literature, a question arises: What type of a model should we use? In this research our aim is to identify the parameters of a neuron model based on recorded stimulus-response data. As the response data do not reflect any membrane potential information but the distribution of the neural spikes instead, a model reflecting the firing rate will be of benefit for this research. So, one may eliminate the complicated models like Hodgkin–Huxley or Morris-Lecar. Instead, we may use a more generic model where the number of neurons can be set to any desired value. Based on these facts, a continuous time generic dynamical recurrent neural network (CTRNN) model can fit this purpose. CTRNNs can be modeled into two forms. One employs the membrane potential variable as its states (but no channel-related dynamics explicitly modeled; they are embedded into the model) and the other presents the dynamics of the neural firing rates directly as states. The former can provide the firing rate as an output variable. The two types have been proven to be equivalent [6]. In this research, we prefer the first one, namely the membrane potential-based one and the firing rate will be mapped through a sigmoidal function (see Section 2.1 for details). In addition, some of the neurons in the selected CTRNN can be made excitatory and others inhibitory. Doing this will allow modeling the firing and refractory response of the neuron more accurately. The dynamic properties of the neuron membrane are represented by time constants and the synaptic excitation and inhibition are represented as network weights (scalar gains). Though not the same, a similar excitatory-inhibitory structure has been utilized in numerous studies such as [10–12].

Parameter identification

Having chosen the model structure, we need to decide how the parameters will be estimated. The first discussion is centered around the structure of the stimulus driving the neural network. There can be various forms for stimulus. As the study targets the auditory cortex, a sine-related stimulus can be chosen where a stimulus modeled by a Fourier series seems to be an appropriate choice.

Concerning parameter estimation, the one applicable choice is to develop a likelihood-based approach as one can only talk about the statistics of the collected spike times. As the timing is stochastic and supposed to obey inhomogeneous Poisson statistics, we can employ a maximum likelihood estimation procedure. The likelihood function will be derived from the inhomogeneous Poisson probability mass function or a more specific one developed by [13, 14]. The latter is expected to provide a better identification result. The reason for this is that the second likelihood is a function of firing rate and individual spike times, whereas the former only requires the number of spikes rather than the firing rate. So the firing rate output of an identified CTRNN is expected to approach the true firing rate as the identification algorithm knows the location of the spikes.

Challenges

There are certain challenges in this research. First of all, we will most probably not be able to have a reasonable estimate just from a single spiking response data set, as we do not have continuous response data. This is also demonstrated in related kernel density estimation research such as [15–18]. From these sources, one will easily note that repeated trials and superimposed spike sequences are required to obtain meaningfully accurate firing rate information from the neural response data. In a real experiment environment, repeating the trials with the same stimulus profile will not be appropriate, as the repeated responses of the same stimulus are found to be attenuated. Because of this issue, a new stimulus should be provided at each excitation. This can be provided by choosing a fixed amplitude and frequency but a randomly shot phase angle for our Fourier series stimulus. Secondly, in the likelihood estimation, the complete data from the beginning will be used in the likelihood optimization. This will be a computational challenge, as very large data will be accumulated in each computation step. When considering an experiment, we collect the data only by providing a random stimulus entry to the animal (experiment subject) and record the spike counts and locations. As an animal is not involved in the computational part of the random stimuli-based experiments, a high-performance computing (HPC) facility can be used without the need of any wet experimental element. In this research, we are employing the high-performance computing facilities (TRUBA/TR-GRID) of the National Academic Information Center (ULAKBIM) of the Turkish Scientific and Technological Research Institution (TUBITAK).

Previous studies

This work is a fairly novel attempt. There are very few studies in the literature that have a similar goal. Some examples can be given e.g., [13, 19–22]. The work in [19] presents a system identification study based on maximum likelihood estimation of the internal parameters of an integrate and fire neuron model. The likelihood function is derived from firing probabilities through a local Bernoulli approximation. Chornoboy et al. [20] aims at the detection of the functional relationships between neurons. Rather than modeling an individual neuron, it involves a characterization of the neural interactions through maximum likelihood estimation. Paninski [21] is similar to [19]. A thorough explanation of maximum likelihood explanation is presented with an application to a linear-nonlinear Poisson cascade and an integrate and fire model generalized linear model. It also presents a comparison with a traditional spike triggered average estimator. Smith and Brown [22] presents a similar work to that of [19, 21] with a different model. The model involves an estimation of a conditional intensity function modulated by an unobservable latent state-space process. The study also involves the identification of the latent process. Both estimation approaches are based on the maximum likelihood method. Paninski [21, 22] apply the expectation maximization method to the solution of the maximum likelihood problems. For a more general discussion on the application of statistical techniques and their challenges in theoretical and computational neuroscience, interested readers can refer to [23].

This research has some similarities with [19, 21] due to the application of the maximum likelihood method to a neural network identification problem. However, the model used in this research is quite different from the ones in those sources. Instead of an integrate and fire model, we prefer a more general continuous time recurrent neural network due to its universal approximation capability, which is expected to be an advantage to model a multi-cellular region of the nervous system. In addition, their dynamical properties are closer to network models such as Hodgkin–Huxley or Morris–Lecar equations. Research such as [24, 25] implements a generic neural network model that is of the static feed-forward type. Based on the above, we can say that this study can be considered a novel contribution to the neuroscience literature. In addition, the work performed in [13, 19–22] is too elaborate in statistical theory with a very limited discussion on how to apply the theory to neuron modeling. This restricts the reproducibility of the research. This text also concentrates on how to apply the theory to the identification problem using computational tools such as MATLAB to increase its reproducibility.

Models and methods

Continuous time recurrent neural networks (CTRNN)

The continuous time recurrent neural networks have a similar structure to that of discrete time counterparts that are often met in artificial intelligence studies. In Fig. 1, it is possible to see a general continuous time network that may have any number of neurons.

Fig. 1.

a A generic recurrent neural network structure. The stimulus means external inputs to the network. b A simple recurrent network with one excitatory unit and one inhibitory unit, with both units having non-linear sigmoidal gain functions. Here, each unit represents a population of neurons. We assume that the recorded responses are inhomogeneous Poisson spike trains based on the continuous rate generated by the state of the excitatory unit

The mathematical representation of this generic model can be written as [5]:

| 1 |

where τi is the time constant (seconds), Vi is the membrane potential of the ith neuron (in millivolts), Wij is the synaptic connection weight between the ith and jth neurons (mV⋅ s), Cik is the connection weight from the ith input to the kth neuron (in kΩ ) and Ik is the kth input (in μA’s). The term is a membrane potential-dependent function that acts as a variable gain on the synaptic inputs from the jth neuron to another neuron. It can be shown by a logistic sigmoid function that can be written as:

| 2 |

where Γj is the maximum rate ( ) at which the jth neuron can fire, hj is a soft threshold parameter of the jth neuron (in millivolts) and aj is a slope constant (in inverse millivolts or ). This is the only source of non-linearity in (1). Similar functional forms are also encountered in more complicated neuron models such as Hodgkin–Huxley equation [1]. The equations describing the dynamics of the channel activations and inactivations involve sigmoid functions like (2). The work by [6] shows that (2) provides a relationship between the firing rate rj and the membrane potential Vj of the jth neuron. In the sensory nervous system, some neurons have excitatory synaptic connections while some have inhibitory ones. This fact is reflected in the model in (1) by assigning negative values to the weight parameters that are originating from neurons with inhibitory synaptic connections. At this point, we have to note that CTRNNs may have any number of neurons with multiple inputs, outputs and layers (see Fig. 1a). Depending on the applications, a complicated neural network may or may not be necessary. Regardless, having large numbers of neurons will constitute a computational burden. As we are aiming to prove the methodology presented in this text, it will be beneficial to start with a basic model. This should be helpful, as there are a very few number of similar studies that can guide the researchers. So we chose a CTRNN with only two neurons. In this context, we will assume that the dynamics of the excitatory and inhibitory members of a part of the auditory cortex are lumped into two neurons. Here, one neuron will represent the average response of the excitatory neurons and be denoted by subscript .e and the other will be denoted by subscript .i and represent the average response of the inhibitory neurons in the network. The stimulus will also be represented by a single input signal and distributed to the neurons by weights. As stated, this approach is preferred to validate the development in this research. Of course, it can be extended to a network with any number of neurons and layers (e.g., (1)). So a basic excitatory and inhibitory continuous time recurrent dynamical network can be written as:

| 3 |

| 4 |

where Ve and Vi are the membrane potentials of the individual excitatory and inhibitory neurons, respectively. As mentioned, the response of all excitatory and inhibitory units is lumped into two single neurons connecting to the excitatory and inhibitory synapses respectively. The stimulus is represented by a single input that is I. In addition, in order to suit the model equations to the estimation theory formalism, the time constant may be moved to the right-hand side as shown below:

| 5 |

where βe and βi are the reciprocals of the time constants τe and τi. They are taken to the right for easier manipulation of the equations. Note that this equation is written in matrix form to suit the formal non-linear system forms. A descriptive illustration related to (5) is presented in Fig. 1b. It should also be noted that, in (4) and (5) the weights are all assumed as positive coefficients and they have signs in the equation. Hence, negative signs indicate that the originating neuron is inhibitory (tend to hyper-polarize the other neurons in the network).

Inhomogeneous Poisson spike model

The theoretical response of the network in (4) will be the firing rate of the excitatory neuron, . In the actual environment, the neural spiking due to the firing rate is available instead. While introducing this research, it was stated that these spiking events conform to an inhomogeneous Poisson process that is defined as:

| 6 |

where

| 7 |

is the mean number of spikes based on the firing rate that varies with time and N(τ) indicates the cumulative total number of spikes up to time τ so that is the number of spikes within the time interval .

In other words, the probability of having k number of spikes in the interval is given by the Poisson distribution above.

Consider a spike train in the time interval (0, T) (here so t and Δt become t = 0 and Δt = T). Here the spike train is described by a list of the time stamps for the K spikes. The probability density function for a given spiking train can be derived from the inhomogeneous Poisson process [13, 14]. The result reads:

| 8 |

This probability density describes how likely a particular spike train is generated by the inhomogeneous Poisson process with the rate function . Of course, this rate function depends implicitly on the network parameters and the stimulus used.

Maximum likelihood methods and parameter estimation

The network parameters to be estimated are listed below as a vector:

| 9 |

which includes the time constants and all the connection weights in the E-I network. Our maximum-likelihood estimation of the network parameters is based on the likelihood function given by (8), which takes the individual spike timings into account. It is well known from estimation theory that the maximum likelihood estimation is asymptotically efficient, i.e., reaching the Cramér-Rao bound in the limit of large data size. To extend the likelihood function in (8) to the situation where there are multiple spike trains elicited by multiple stimuli, consider a sequence of M stimuli. This means that we drive the network in (5) M times by generating M different stimuli at each trial. If and are the stimuli for the and trials, respectively, for , for all cases where j ≠ k. Suppose the m-th stimulus (m = 1, … , M) elicits a spike train with a total of spikes in the time window and the spike timings are given by . By (8), the likelihood function for the spike train is:

| 10 |

where is the firing rate in response to the m-th stimulus. Note that the rate function depends implicitly on the network parameters and on the stimulus parameters. The left-hand side of (10) emphasizes the dependence on network parameters , which is convenient for parameter estimation. The dependence on the stimulus parameters will be discussed in the next section.

We assume that the responses to different stimuli are independent, which is a reasonable assumption when the inter-stimulus intervals are sufficiently large. Under this assumption, the overall likelihood function for the collection of all M spike trains can be written as:

| 11 |

By taking a natural logarithm, we obtain the log likelihood function:

| 12 |

The maximum-likelihood estimation of the parameter set is given formally by:

| 13 |

Stimulus

As discussed in Section 1.3, we will model the stimulus signal by a phased cosine Fourier series:

| 14 |

where is the amplitude, is the frequency of the n-th Fourier component in radians/sec and is the phase of the component. Here the amplitude and the base frequency (in Hz) are fixed but the phase will be a randomly chosen from a uniform distribution between radians. The amplitude parameter is fixed for all mode n as .

Results

In this section, we will summarize the functional and numerical details of the neural network parameter estimation algorithm.

Details of the example model

This section is devoted to the detailed presentation of the simulation set-up. A numerical example will be presented that will demonstrate our approach. In the example application, the algorithms presented in Section 2.3 are applied to probe an E-I network. In order to verify the performance of the parameter estimation, we have to compare the estimates with their true values. So we will need a set of reference values of the model parameters in (5). These are shown in Table 1. The example model can also be seen in Fig. 1b.

Table 1.

The true values of the parameters of the network model in (5). These are the parameters to be estimated

| Parameter | Unit | True value (θ) |

|---|---|---|

| β e | 50 | |

| β i | 25 | |

| w e | kΩ | 1.0 |

| w i | kΩ | 0.7 |

| w ee | mV⋅ s | 1.2 |

| w ei | mV⋅ s | 2.0 |

| w ie | mV⋅ s | 0.7 |

| w ii | mV⋅ s | 0.4 |

Our model in (5) has two more important components; the gain functions and . These are obtained by setting j in (2) by either ‘e’ or ‘i’. So, we have six additional parameters that have a direct effect on the neural model behavior. This research targets the estimation of the network weights and reciprocal time constants only. Because of that, the parameters of the gain functions are assumed to be known, and they have the values as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The parameters of the sigmoidal gain functions in (2) for the excitatory (e) and inhibitory (i) neurons of the example model

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Γe | 100 | |

| a e | 0.04 | |

| h e | 70 | mV |

| Γi | 50 | |

| a i | 0.04 | |

| h i | 35 | mV |

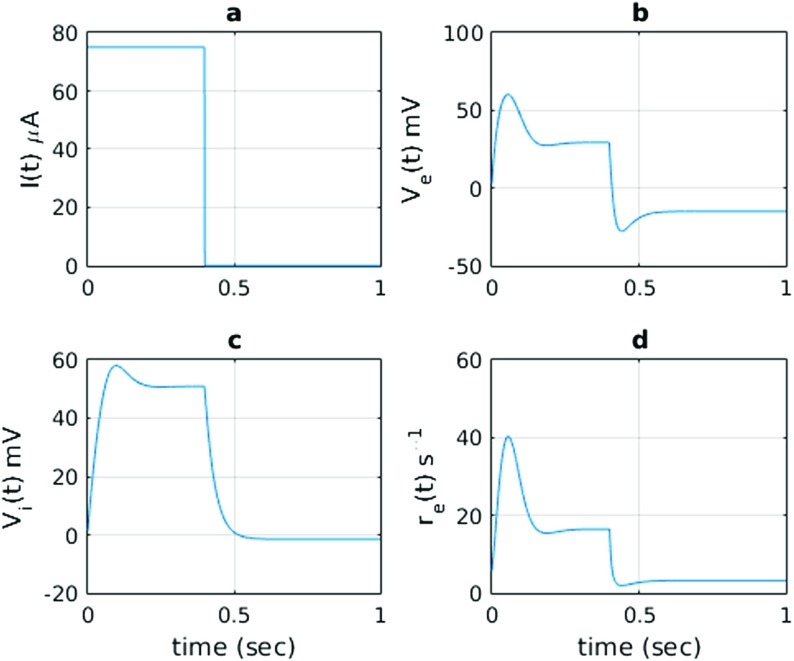

This set of parameters (Tables 1 and 2) allows the network to have a unique equilibrium state for each stationary input. The parametric values are intendedly selected to provide a realistic model. This can be understood from the responses against a wide pulse stimulus as shown in Fig. 2. To demonstrate the excitatory and inhibitory characteristics of our model, we can stimulate the model with a square wave (pulse) stimulus as shown in Fig. 2a. The pulse stimulus is chosen to be at levels as much as 75 μA. As seen from Fig. 2b and c, membrane potentials ( and ) rise to levels as much as 50 mV, which can also be seen in realistic neurons. In addition to those, the relative levels of synaptic weights are chosen such that we notice a reasonable level of inhibitory behavior in the response of the excitatory membrane potential. When a narrow pulse stimulus current is injected, as shown in Fig. 3a, it is possible to notice that a response (Fig. 3b) comparable to an action potential is generated. It had a refractory period after the stimulus ceased, which is due to the continuing action of the inhibitory neuron. It can be said that the network has shown both transient and sustained responses. In Fig. 2d, the excitatory firing rate response , which is related to the excitatory potential as , is shown. The response is slightly delayed, which leads to the depolarization of the excitatory unit until t = 250 ms. This delay is also due to the subsequent re-polarization and plateau formation in the membrane potential of the excitatory neuron. The firing rate is higher during excitation and lower in the subsequent plateau and repolarization phases (Fig. 2d). In addition, a similar level of parameters is also seen in synaptic conductances of the neurons discussed in [26].

Fig. 2.

The network model in Fig. 1b in response to a square-wave stimulus I(t). The states of the excitatory and inhibitory units, V e(t) and V i(t), are shown, together with the continuous firing rate of the excitatory unit, . The firing rate of the excitatory unit (bottom panel) has a transient component with higher firing rates, followed by a plateau or sustained component with lower firing rates

Fig. 3.

Narrow pulse stimulus (a) and its response in the excitatory membrane potential (b). Note that the response is comparable to an action potential in levels and shape

Stimulus and response

The stimulus to be used in this example is given in (14). In this application, will be constant for all mode n (n = 1…NU ). The phase angles ϕn will be assigned randomly (uniformly distributed between [−π,π]) at each iteration. It should be noted that we do not intend to provide a random stimulus here. The phase angles will be randomly drawn at the beginning of each iteration and stay constant until the new iteration starts. Due to the random assignment, they will be different for each iteration. This will yield a different Fourier series stimulus at each iteration. In the case of an experiment, this is critical, as the response of a neuron may cease after repeating the stimulation with the same stimulus profile a few times.

It might be beneficial to note the response of the system to this stimulus at different component sizes (NU ) (see Fig. 4). The associated membrane potential responses are shown in Figs. 5 and 6 (V e and V i).

Fig. 4.

The variation of cosine stimulus for a different number of components NU. The sizes are a NU = 5, b NU = 10, c NU = 20, d NU = 30, e NU = 40, and f NU = 50. The amplitude parameters are An = 100, f0 = 3.333 Hz and ϕn are randomly assigned from a set uniformly distributed between [−π,π]

Fig. 5.

The variation of excitatory membrane potential to the cosine stimulus for a different number of stimulus components NU. The sizes are a NU = 5, b NU = 10, c NU = 20, d NU = 30, e NU = 40 and f NU = 50. The amplitude parameters are An = 100, f0 = 3.333 Hz and ϕn are randomly assigned from a set uniformly distributed between [−π,π]

Fig. 6.

The variation of inhibitory membrane potential to the cosine stimulus for a different number of stimulus components NU. The sizes are a NU = 5, b NU = 10, c NU = 20, d NU = 30, e NU = 40, and f NU = 50. The amplitude parameters are An = 100, f0 = 3.333 Hz and ϕn are randomly assigned from a set uniformly distributed between [−π,π]

As the network will have a typical frequency response where it will be more sensitive, the base frequency may also be of concern. An analysis may be beneficial here. In Fig. 7, it is possible to see the mean firing rate response of the network to the stimulus in (14) with μA and to a varying base frequency up to 40 Hz. This result reveals that larger mean firing rate responses are obtained when the frequency is lower. This is apparent when the value of is comparably lower (5, 10, and 20). Hence, a choice of Hz seems reasonable. For example, we can choose, Hz.

Fig. 7.

The variation of the mean excitatory firing rate against base frequency f0 of the cosine stimulus for a different number of stimulus components NU. The sizes are a NU = 5, b NU = 10, c NU = 20, d NU = 30, e NU = 40 and f NU = 50. The amplitude parameters are: An = 100 and ϕn are randomly assigned from a set uniformly distributed between [−π,π]

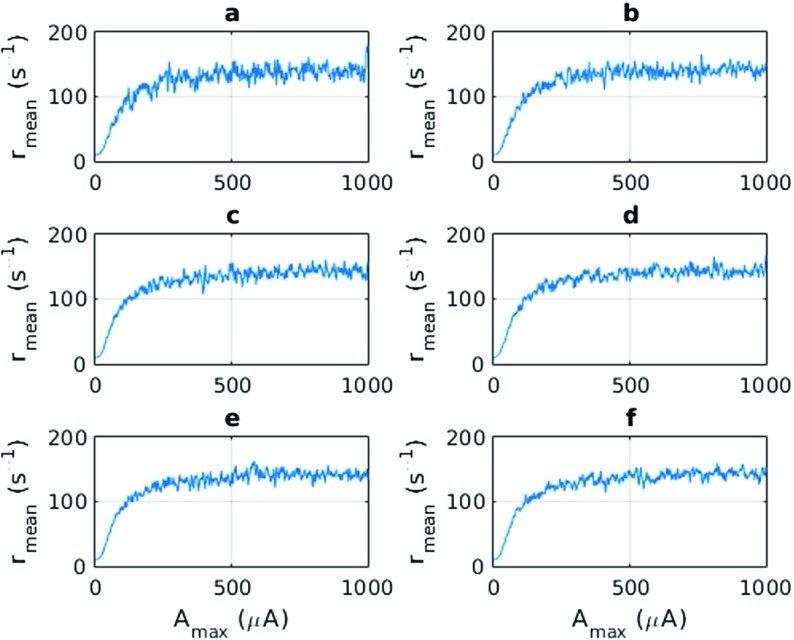

Another interesting analysis may be performed on the response of the neurons to amplitude parameter (note we are holding the amplitude parameter constant for all mode n). In Fig. 8, we can observe what happens when the same stimulus with a varying amplitude parameter is applied to the neurons. As with the frequency response analysis, we still perform the analysis for different values of . The mean firing rate does not seem to vary when there are large amplitudes. It can be concluded from Fig. 8 that there is a mean firing rate of approximately 150 . Therefore, if one considers the range of 10–90% of the maximum value as a dynamic range, we can say that the dynamic range of the network lies in the range of 20 − 350 μA.

Fig. 8.

The variation of the mean excitatory firing rate against the amplitude parameter of the cosine stimulus for a different number of stimulus components NU. The sizes are a NU = 5, b NU = 10, c NU = 20, d NU = 30, e NU = 40 and f NU = 50. The amplitude parameters are: An = 100 and ϕn are randomly assigned from a set uniformly distributed between [−π,π]. The frequency is the same as f0 = 3.333 Hz

Spike generation

As discussed in Section 1.2, we will not have any measurement of membrane potential or . Instead, we will record the spike timings of the neuron and try to solve a maximum likelihood estimation of network parameters using the likelihood function in (11). Because of that, the simulation needs a method to generate the spike timings of the neurons. As we know from [9] that the spikes obey an inhomogeneous Poisson distribution, we can obtain the spike timings from a simulation of an inhomogeneous Poisson process of which the event or firing rate is given by:

| 15 |

There are numerous methodologies to generate the Poisson events given the event rate . These range from discrete simulation [14] to thinning [27]. Discrete simulation may be beneficial when solving the dynamical models by fixed step solvers such as Euler Integration or Runge–Kutta methods. The only disadvantage of this approach is that it confines the spikes into discrete time bins. However, if there is a sufficiently small discrete time bin such as Δt = 0.1 ms, the statistical distribution of the spikes should approach that of an inhomogeneous Poisson process [14]. Discrete simulation of neural spiking can be summarized as:

The firing rate of any neuron is given as r(t)

Find the probability of firing at time by evaluating where Δt is the integration interval. It should be as small as 1 ms.

Compute a random variable by drawing a sample from a distribution that is uniform between 0 and 1. Define this as where U stands for uniform distribution.

If fire a spike at , otherwise do nothing.

Collect spikes as where will be the number of spikes obtained at a single run of simulation.

Step-by-step description of the problem and simulation

The working principles in the example problem can be described in a step-by-step fashion as:

A single run of simulation will last for s.

The neuron model in (5) will be simulated at the true value of parameters that are given in Tables 1 and 2 and firing rate data are stored as where m is the current number of simulation.

Firing rate data are used to generate neural spikes in the run using the methodology defined in Section 3.3. These data will be used to compute the likelihood. The number of spikes will be at the run.

Repeat the simulation times to obtain enough number of spikes.

The spiking data needed by (12) will be obtained at the 4th step. However, the firing rate component of (12) should be computed at the current iteration of the optimization.

Run an optimization algorithm of which the objective computes the firing rate at the current iterated value of the parameters but the spikes from Step 4.

Optimization algorithm

Theoretically, any optimization algorithm ranging from gradient descent to derivative-free simulated annealing can be utilized in computational parts of this research. Most of these algorithms are provided as ready-made routines in the optimization and global optimization toolboxes of MATLAB. Regardless of the type of algorithm, all of the methods converge to a local optimum and require an initial guess. As a result, one needs to start from multiple initial guesses to have an adequate amount of local optimum that will allow to detect the global one. If we have a convex problem, different initial guesses are expected to converge to the same local optimum, which is the desirable situation. However, this may not always be the case in problems similar to that of this research. In any case, the main criterion on the choice of the algorithms is the speed of convergence. Although we have an HPC computing facility, we should choose the fastest algorithm, as we need to collect a huge amount of data to conclude about the efficiency of the project. Some initial evaluations suggested that local optimizer routines provided by MATLAB’s fmincon should be preferred concerning speed and computational resource considerations. MATLAB’s global optimization algorithms such as genetic algorithms, simulated annealing, or pattern search may also be utilized to solve the same problem. However, they seem to be computationally more intensive and they are also designated officially as local optimizers. Thus, it may be necessary to repeat the trials a few times to find an optimum. This is not desired if we apply this research to an experiment. The fmincon algorithm requires gradient information, but it can be provided by itself through finite difference approximations. There will be 14 (this number equates to the number of cores in a local machine) initial guesses and each initial run will be performed on one core. The whole optimization will be run parallel by the parfor parallel for loop structure of MATLAB. The initial guesses are generated randomly from a uniform distribution.

Simulation data

The nominal data in the current problem are given in Table 3. In order to calculate the effect of the different number of stimulus components , amplitude level , and number of trials , we will repeat the problem for a set of different values of those parameters. The different values of those parameters are provided in Table 4.

Table 3.

Typical data related to the simulation scenario

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation time | T f | 3 sec |

| Number of trials | N it | 100 |

| # of Components in stimulus | N U | 5 |

| Method of optimization | N/A | Interior point gradient descent (MATLAB) |

| # of true Parameters | Size(θ) | 8 |

| Stimulus amplitude (μ A) | 100 | |

| Base Frequency | f 0 | 3.333 Hz |

Table 4.

The data related to the analysis of the problem for the different number of trials , number of stimulus components NU, stimulus amplitude

| Parameter | Symbol | Value(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of trials | N it | 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 |

| # of components in stimulus | N U | 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 |

| Stimulus amplitude (μ A) | 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 |

The initial levels of membrane potentials of excitatory and inhibitory neurons are and . As we will most probably not know the true values of those conditions, an assumption of zero values should be sufficient. We will repeat the simulation 20 times for each case, so that we will have a sufficient number of results to perform a statistical analysis.

Presentation of the results

In this section, we discuss the numerical results of the maximum likelihood estimation of the parameters of our neuron model in (5) using maximum likelihood estimation through the maximization of (12) against parameters in (9). The optimization is performed using the gradient-based interior-point method provided by MATLAB’s fmincon algorithm. All the cases in Table 4 are examined under the conditions in Table 3. The overall results are presented in two forms. In Tables 5 and 6, we can see the results of an estimate obtained for the conditions given in Table 3. In the second table, we can also see the percent errors related to each estimated parameter. Secondly, in Figs. 9, 10, 11 and 12 the variation of the mean square (w.r.t the true parameters in Table 1) with different values of the number of stimulus components , amplitude parameter , number of trials , and base frequency , respectively, is shown.

Table 5.

Results of maximum likelihood estimation (mean values ) of θ when the conditions in Table 3 are applied

| 49.778 | 25.010 | 1.010 | 0.684 | 1.227 | 2.103 | 0.740 | 0.505 |

Table 6.

Mean square and percent errors of the parameters in (9) after estimation

| MSE(θ) | Value | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.8328 | 0.443 | |

| 5.2364 | 0.043 | |

| 0.0015 | 1.048 | |

| 0.0046 | 2.178 | |

| 0.0072 | 2.253 | |

| 0.0403 | 5.197 | |

| 0.0234 | 5.768 | |

| 0.0482 | 26.251 |

Fig. 9.

The variation of individual mean square errors between estimated and true parameters against varying stimulus component size NU. Here, Nit = 100, and f0 = 3.333 Hz

Fig. 10.

The variation of individual mean square errors between estimated and true parameters against varying stimulus amplitude parameter . Here Nit = 100, NU = 5 and f0 = 3.333 Hz

Fig. 11.

The variation of individual mean square errors between estimated and true parameters against varying sample (iteration) size Nit. Here NU = 5, and f0 = 3.333 Hz

Fig. 12.

The variation of individual mean square errors between estimated and true parameters against varying base frequency f0. Here, Nit = 100, and NU = 5

One can argue that the percent error associated with parameter is too large (> 25%). At this point, it will be convenient to present the results related to a scenario similar to that of Table 3 but with a larger sample size Nit = 400 . The associated results are shown in Tables 7 and 8. In this case, there is a considerable improvement in the percent error associated with parameter wii (level of decrease is near one-third).

Table 7.

Results of maximum likelihood estimation (mean values ) of θ when the conditions in Table 3 are applied with a larger sample size Nit = 400

| 49.809 | 24.981 | 1.004 | 0.692 | 1.209 | 2.045 | 0.704 | 0.435 |

Table 8.

Mean square and percent errors of the parameters in (9) after estimation

| MSE(θ) | Value | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.2332 | 0.3811 | |

| 0.6248 | 0.073 | |

| 0.0002 | 0.4267 | |

| 0.0015 | 1.1408 | |

| 0.0018 | 0.7502 | |

| 0.0098 | 2.2819 | |

| 0.0036 | 0.6333 | |

| 0.0140 | 8.8161 |

Discussion and conclusions

Summary and general discussion

This research is devoted to a theoretical study of model fitting to noisy stimulus/response data obtained from sensory neurons. Sensory neurons are known to code transmitted information in the temporal position of the peaks of their generated successive action potentials. It is also known that the temporal distribution of the peaks obey an inhomogeneous Poisson process where the event rate is considered as a neural firing rate. This firing characteristic allows us to implement a maximum likelihood estimation of the parameters of the fitted model. We use a likelihood function derived from a local Bernoulli process, which is a function of both the firing rate and the location of individual spikes. The stimulus is modeled as a real phased cosine Fourier series. The maximization of the likelihood is performed by the gradient-based interior-point method (available as the fmincon function in MATLAB).

Evaluation of the results

The main results of this research are compiled into four graphical illustrations, as shown in Figs. 9, 10, 11, and 12. These present the mean square error of estimation against the number of stimulus components , amplitude parameter , sample size (or number of iterations) , and base frequency of stimulus . According to these results, the following comments can be made:

The mean square errors of estimation for each parameter are affected from , , and in some level.

However, the main factor that yields a noticeable pattern regardless of the parameter in consideration is the number of samples taken (Nit ). As Nit increases, the mean square errors decrease regardless of the parameter in consideration.

does not seem to have a predictable effect on the error levels. However, Fig. 9 reveals that small component counts (small such as ) seem to provide a better result.

The value of has a considerable influence on the mean square errors of , , , and . However, large values of this setting have no benefit. It seems that the range is a reasonable choice where smaller levels of errors are noticed.

Concerning the base frequency , we can conclude that too low and too high frequencies should be avoided. The results also show that the preferred frequency value (f0 = 3.333 Hz) in this example to generate the results in Figs. 9, 10, 11 seems a good compromise.

Comparison with similar studies

Comparison with a different likelihood

It will be beneficial to compare the results of this study with a similar one with the same model in (5) with the same nominal parameters in Table 1 and same stimulus structure as in (14). Such a research is presented in [28]. Here the standard Poisson probability mass function is used as the likelihood instead of the Bernoulli-based derivation in (11). That is:

| 16 |

The optimization procedure is exactly the same as that of the current work. Based on the results of the current study and that of [28], we can say that the results of this work are considerably better. This can be understood from the mean square errors presented in Fig. 11. Even the cases with lesser samples (lower values) provided much lower mean square errors than the cases in [28] with a larger number of samples. The difference should be due to the incorporation of the individual spike timings into the evaluation algorithm. In the work of [28], only the spike count in the trial is taken into account by the likelihood estimation (as understood from (16)). Incorporating the spike timings improves the estimation accuracy.

Comparison with other studies in literature

It will be beneficial to compare the results of this study with a few different studies in the neuroscience literature. Examples are [22, 29, 30]. As done in this paper, those studies worked on estimation of neural model parameters by maximum likelihood methods. [22] estimates two models, one with 23 parameters and one with four parameters. In both attempts, some mean estimates appeared to deviate as much as from their true parameters values. The error levels vary from parameter to parameter and lie in the range . However, most of the parameters have error levels larger than . In [30], the error levels seem to be improved, and they lie in the range . However, this model has fewer parameters (only three) and thus it might be a trivial result. In [29], some time-dependent variables are being estimated using likelihood methods. Based on the results obtained in the mentioned research, the error levels vary with the region of the signals in consideration. Although the trials are repeated 120 times to perform model fitting, the percent estimation error stays around 30% or larger.

Based on the results of this research and the compiled ones above, we can deduce that:

The level of efficiency of the estimation algorithm is definitely acceptable. The estimation error levels are comparable to that of various researches performed before.

Large estimation percent errors appear only for few parameters in this research, whereas works such as [22] appear to have larger percent estimation errors for many parameters. Moreover, it is possible to further decrease the level of those errors in this study by increasing the number of samples (see Tables 6 and 8).

These comparative results can be considered as validation for the success of this work.

Future work

This study is a fairly new contribution to the theoretical neuroscience literature. Thus, there are a few points that should be addressed in future studies:

Different stimulus profiles can be applied. These may be pure noise, exponential function, ramp or parabola.

An interesting application on the same model is to derive the stimulus through an optimal design process. At least the amplitude and frequency component can be optimally calculated using information maximization approaches. Generally, the Fisher information metric is the main objective function here. An approach is discussed in [31].

More specific and complicated models can be processed using the same algorithm. This will be an interesting topic and will also provide a means of comparison to this work.

Using a specific model that can provide modulated bursts of firing, it is possible to imitate the behavior of a sensory neural network when noise is taken into account (may be the basic planar Hindmarsh–Rose equations). So the model used in this research can be trained using the spiking data available from the simulation of a new model.

Funding Information

This study was partially supported by the Turkish Scientific and Technological Research Council’s DB-2219 Grant Program.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work was partially supported by the Turkish Scientific and Technological Research Council (TÜBİTAK) 2219 Research Program. The computational facilities needed in this research were provided by the High Performance Computing (HPC) center TRUBA/TR-GRID owned by the National Academic Information Center (ULAKBIM) of TURKEY. The work started at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine while the corresponding author (R.O. DORUK) was employed there. The work continued in Atilim University after 2014 where the corresponding author is still employed.

References

- 1.Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 1952;117(4):500. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.FitzHugh R. Impulses and physiological states in theoretical models of nerve membrane. Biophys. J. 1961;1(6):445–466. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(61)86902-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris C, Lecar H. Voltage oscillations in the barnacle giant muscle fiber. Biophys. J. 1981;35(1):193–213. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84782-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ledoux, E., Brunel, N.: Dynamics of networks of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in response to time-dependent inputs. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, 5 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Beer RD. On the dynamics of small continuous-time recurrent neural networks. Adapt. Behav. 1995;3(4):469–509. doi: 10.1177/105971239500300405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller KD, Fumarola F. Mathematical equivalence of two common forms of firing rate models of neural networks. Neural Comput. 2012;24(1):25–31. doi: 10.1162/NECO_a_00221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerstner W, Kreiter AK, Markram H, Herz AV. Neural codes: Firing rates and beyond. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1997;94(24):12,740–12,741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herz AV, Gollisch T, Machens CK, Jaeger D. Modeling single-neuron dynamics and computations: A balance of detail and abstraction. Science. 2006;314(5796):80–85. doi: 10.1126/science.1127240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shadlen MN, Newsome WT. Noise, neural codes and cortical organization. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1994;4(4):569–579. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hancock KE, Davis KA, Voigt HF. Modeling inhibition of type II units in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. Biol. Cybern. 1997;76(6):419–428. doi: 10.1007/s004220050355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock KE, Voigt HF. Wideband inhibition of dorsal cochlear nucleus type IV units in cat: a computational model. Annal Biomed. Eng. 1999;27(1):73–87. doi: 10.1114/1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Rocha J, Marchetti C, Schiff M, Reyes AD. Linking the response properties of cells in auditory cortex with network architecture: Cotuning versus lateral inhibition. J. Neurosci. 2008;28(37):9151–9163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1789-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown EN, Barbieri R, Ventura V, Kass RE, Frank LM. The time-rescaling theorem and its application to neural spike train data analysis. Neural Comput. 2002;14(2):325–346. doi: 10.1162/08997660252741149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eden, U.T.: Point process models for neural spike trains. Neural Signal Processing: Quantitative Analysis of Neural Activity, 45–51 (2008)

- 15.Koyama S, Shinomoto S. Histogram bin width selection for time-dependent Poisson processes. J. Phys. A. 2004;37(29):7255. doi: 10.1088/0305-4470/37/29/006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nawrot M, Aertsen A, Rotter S. Single-trial estimation of neuronal firing rates: from single-neuron spike trains to population activity. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1999;94(1):81–92. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(99)00127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimazaki H, Shinomoto S. A method for selecting the bin size of a time histogram. Neural Comput. 2007;19(6):1503–1527. doi: 10.1162/neco.2007.19.6.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimazaki H, Shinomoto S. Kernel bandwidth optimization in spike rate estimation. J. Comput. Neurosci. 2010;29(1-2):171–182. doi: 10.1007/s10827-009-0180-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brillinger DR. Maximum likelihood analysis of spike trains of interacting nerve cells. Biol. Cybern. 1988;59(3):189–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00318010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chornoboy E, Schramm L, Karr A. Maximum likelihood identification of neural point process systems. Biol. Cybern. 1988;59(4):265–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00332915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paninski L. Maximum likelihood estimation of cascade point-process neural encoding models. Netw. Comput. Neural Syst. 2004;15(4):243–262. doi: 10.1088/0954-898X_15_4_002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith AC, Brown EN. Estimating a state-space model from point process observations. Neural Comput. 2003;15(5):965–991. doi: 10.1162/089976603765202622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu MCK, David SV, Gallant JL. Complete functional characterization of sensory neurons by system identification. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;29:477–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiMattina C, Zhang K. Active data collection for efficient estimation and comparison of nonlinear neural models. Neural Comput. 2011;23(9):2242–2288. doi: 10.1162/NECO_a_00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiMattina, C., Zhang, K.: Adaptive stimulus optimization for sensory systems neuroscience. Front. Neural Circuit, 7 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Pham, T., Haas, J.: Electrical synapses between inhibitory neurons shape the responses of principal neurons to transient inputs in the thalamus. bioRxiv p 186585 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Lewis PA, Shedler GS. Simulation of nonhomogeneous Poisson processes by thinning. Naval Res. Logistics Quarter. 1979;26(3):403–413. doi: 10.1002/nav.3800260304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doruk, O., Zhang, K.: Building a dynamical network model from neural spiking data: Application of Poisson likelihood. arXiv:1710.03071 (2017)

- 29.Truccolo W, Eden UT, Fellows MR, Donoghue JP, Brown EN. A point process framework for relating neural spiking activity to spiking history, neural ensemble, and extrinsic covariate effects. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;93(2):1074–1089. doi: 10.1152/jn.00697.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou GT, Schafer WR, Schafer RW. A three-state biological point process model and its parameter estimation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1998;46(10):2698–2707. doi: 10.1109/78.720372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doruk, R.O., Zhang, K.: Adaptive stimulus design for dynamic recurrent neural network models. arXiv:1610.05561 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]