Abstract

The use of pesticides in agriculture can make their way into the earth and wash into the amphibian system causing ecological stress. This study aims to understand the changes occurring in gill tissues as a result of fenvalerate exposure using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. The intensity ratio of the selected bands I1545/I1657, I2924/I2853, and I1045/I1545 measures changes in proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates. Curve-fitting analysis was performed in the selected band region to analyze the quantitative changes of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates. The band area ratio of CH3/asCH2+ sCH2 shows the absence of a long chain of fatty acids due to fenvalerate treatment. The band area ratio of asCH2/sCH2 increases for higher sublethal concentrations, which shows the lower disorder of lipid acyl chain flexibility. A decrease in lipids was found in lower sublethal concentrations. The secondary structure of proteins affirms β sheet development. Carbohydrate metabolism of gill tissues demonstrates a decrease in glycogen contents. A further decrease in glycogen content and an increase in lactic acid were observed when presented to a fenvalerate concentration. PCA plots indicate distinct variations among the biochemical parameters of the gill tissues. This study provides a quantitative examination of assessing pesticide toxicity in aquatic environments.

Keywords: Toxicity, Pesticides, Fish, FTIR, PCA, Proteins, Lipids, Carbohydrates

Introduction

Oceanic contamination has turned into a worldwide critical issue of late. Pesticides are broadly utilized in agribusiness to help in the generation of good sustenance. Owing to their widespread distribution and toxic nature, pesticides can have a serious impact on the aquatic environment. Utilization of farming pesticides is of interest to scientists to understand the effects of these chemicals on natural communities. Unpredictable and boundless utilization of pesticides in agriculture eventually stimulates risk to aquatic life. They are released into the environment and they never find their target organism; instead, they are washed into the aquatic system [1]. Further, they exert adverse effects on the associated organisms [2]. The long-term effect of poisonous chemicals in these pesticides results in ecological contamination. Fenvalerate is such a pesticide, which is a profoundly toxic synthetic pyrethroid. It is a recently developed type II manufactured pyrethroid because of its enhanced insecticide potential. It is employed to control biting and sucking insects and vermin in cotton, plantations, and grains. The toxic effects of fenvalerate are considered with respect to osmoregulation, hematology, biochemistry, oxidative damage, and histological changes in aquatic organisms [3, 4].

Fishes serve as an essential pointer of ecological stress. However, fish have a poor capacity to metabolize and discharge fenvalerate [5], and in this way is defenseless to even a minute concentration of the pesticide. Repeated introduction to sublethal dosages of a few pesticides can bring about physiological and behavioral changes in fish that decrease populations. The gill is the major route of direct contamination due to its personal contact with the environment. The gills have some essential capacities, for example, breath, acid-base balance, discharge, and osmoregulation.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) is widely recognized as a non-perturbing rapid technique providing data on biomolecules, such as proteins, lipids, and diverse functional groups. The understanding of spectra and peak assignments is the key step in the FTIR examination of any biological sample [6]. It has high sensitivity in detecting small changes in the functional group of biological molecules. Within the limitation of the knowledge of the authors, no reports have been made on fenvalerate toxicity with respect to gill tissues of an edible fish studied using FTIR spectroscopy.

Principal component analysis (PCA) is one of the methods used in chemometric analysis. It is employed for data reduction to identify a small number of factors from a larger number of variables. It is a non-parametric technique for isolating the relevant information from confusing data sets. It allows a primary evaluation of similarity and variation in the spectra taken from a sample. Bearing in mind the above discussion, the present work aims to examine fenvalerate-prompted biochemical changes in the gill tissues of Oreochromis mossambicus fingerlings utilizing FTIR and PCA for short-term (7 days) exposure.

Materials and methods

Collection of materials

For this examination, Oreochromis mossambicus, with a normal body weight of 22 g ± 0.56 (mean + SD) and length in the range 13–15 cm, were gathered from a freshwater source in Puzhal Lake, Redhills, Chennai. Fish were transported to the research facility in plastic sacks with adequate air. They are used as typical fish due to their endurance in an extensive variety of test conditions.

The exploratory plan

The fish were acclimated to the research facility conditions 10 days preceding the analysis in a glass aquarium (150 l) loaded with dechlorinated water. Water-quality attributes were determined. The mean qualities for the test water are: temperature 27.5 ± 1.5°C, pH 7.5 ± 0.03, dissolved oxygen 6.4 ± 0.2 mg/l, alkalinity 250 ± 2.8 mg/l as CaCO3, total hardness 456 ± 3.5 mg/l. The fish were sustained day by day with industrially adjusted fish sustenance sticks. The fish were kept on a photoperiod period of 12-h light/12-h dark. The acute toxicity of fenvalerate to Oreochromis mossambicus was determined using a standard static-renewal technique [7]. The 96-h LC50 for fenvalerate in Oreochromis mossambicus was found to be 30.88 ppb using the Probit analysis method [8]. The one-tenth and one-third LC50 were taken as the lower sublethal concentration (LSL) and the higher sublethal concentration (HSL), respectively. The LSL and HSL of fenvalerate tested are 3.08 ppb and 10.29 ppb. The fish were isolated into three gatherings and put into independent glass aquaria. Group I was kept without pesticide water to serve as a control. Groups II and III were presented to the lower and higher sublethal concentrations of fenvalerate respectively for a period of 7 days. The toxicant in the test chambers was renewed with a fresh solution of the same concentration every 24 h. The experiments were performed in three replicates.

Test chemicals

Commercial-grade fenvalerate (C25H22ClNO3) (20% EC) (Rallis India Ltd., Mumbai, India) was used as part of this study.

FTIR analysis

After treatment, both the experimental and control fish were sacrificed and gill tissues were removed and kept at −70 °C until investigation. The gill samples were homogenized with a saline phosphate solution, pH 7.4, and centrifuged at 125,000 × g for 15 min. ATR crystal was cleaned with dH2O, dried thoroughly, and a new background spectrum was taken before the analysis of a new sample. These homogenate membranes were utilized for FTIR studies [9]. The spectra of gill tissue homogenates were subtracted from the spectrum of the buffer and the wave number values of all functional groups were recorded.

FTIR spectra of tests were recorded at 4000–450 cm−1. IR spectra were obtained by utilizing a PERKIN ELMER Spectrum One FTIR spectrometer equipped with a deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) detector. The instrument was under a continuous dry air purge to eliminate atmospheric water vapor. Interferograms were averaged for 400 scans at 1.0 cm−1 resolution. Perkin Elmer Spectrum programming was utilized for the frequency measurements. The band positions were measured according to the center of weight. The spectra were baseline corrected and normalized to account and correct for noise, sloping baseline effects, and differences in sample thickness or concentration.

Statistics analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 16. Data were analyzed for statistical significance using Student’s t test. A probability level (P value) of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed with SPSS 16.0 programming. It is employed in data reduction to a small number of factors from a larger variable. The PCA software was applied to our mean-centered, second-derivative, and vector-normalized spectral data. The results are presented as score plots. PCA executed in the entire region (4000−400 cm−1) is given as input for the nine samples as the n × n matrix. The factor reduction was obtained by PCA. The input absorption values of the sample (both control and treated) are formed as data matrices. They transform the original measurement variables into new uncorrelated variables called principal components. Input changes into scores and loadings, which are the characteristics of the principal components. They are utilized for quantitative strategies of discriminating samples. The score of the component was plotted to gather data responsible for variability in the FTIR information.

Results and discussion

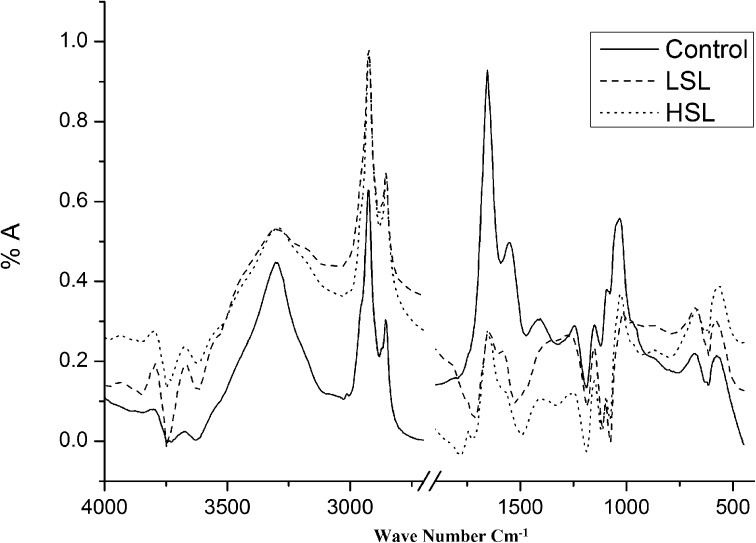

Figure 1 demonstrates the average FTIR spectra of the gill tissues of O. mossambicus control and fenvalerate exposures in the region of 4000−400 cm−1. Table 1 demonstrates the characteristic frequency values and detailed band assignment of the spectra of the sample. The IR spectra of gill tissue are composed of several bands of various functional groups such as lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, and others. Spectral analysis was performed for particular choice groups in the regions 3600−3100 cm−1, 3050−2800 cm−1 and 1800−800 cm−1. Figure 2 demonstrates the spectra normalized at 3297 cm−1 emerging from N-H/O-H stretching modes of proteins and polysaccharides and intermolecular H bonding. The band at 3083 cm−1 is assigned to the N-H stretching of amide B proteins [6]. With a specific end goal to concentrate on the changes in the lipid contents of gill tissues, the 3050−2800 cm−1 region is checked as shown in Fig. 3. The spectra were normalized concerning 2925 cm−1 assigned to the CH2 asymmetric stretching lipid contents of gill tissues. The band at 2873 cm−1 is referred to as the CH3 symmetric stretching of proteins, whereas the band at 2960 cm−1 corresponds to lipids [10, 11]. The ratio of the intensity of absorption of the bands between I2960/I2873 could be utilized as the principal measure of quantity of methyl groups in protein fibers [12]. Moreover, the ratio of I2924/I2853 can be used to monitor the state of biological membranes [13]. As seen from Fig. 3 and Table 2, the intensity of lipids bands diminishes and a move in higher values is noted. The intensity ratio of I2924/I2853 diminishes on account of LSL introduction showing disordering of the unsaturated lipids. On account of HSL, the intensity ratio of I2924/I2853 increments compared to the control. This increase in lipids, because of the introduction to a higher sublethal concentration of fenvalerate exposures, demonstrates an increase of fatty acid concentration. As the lipid assumes the regulation of membrane functions, the high value of this ratio shows a lower disorder of lipid acyle chains in the membranes of this gill tissue [14]. The bands at 1652 and 1541 cm−1 are reported as amide I and II vibrations individually of structural proteins [15, 16]. The amide absorptions are viewed as in protein conformation; consequently, an increase or decrease in the ratio of the intensities of the band ~1540 cm−1 (amide II) and ~1650 cm−1 (amide I) could be ascribed to changes in the composition of the whole protein [12]. The intensity of amide I band decreased in both treatments of gill tissues and the frequency of this band moved to a higher value. The lipid intensity ratio I2924/I2853 shows an increase in its value noted at HSL. An increase in the content of lipids is considered to be important for the regulation of membrane functions in a cell [17]. However, in our study, disturbed metabolism of lipids might be the possible reason for the increase in lipid peroxidation due to pesticide intoxication [18]. The intensity ratio of carbohydrates to I1045/I1545 decreases for both treatments. This may be due to an increase in carbohydrate consumption or due to generalized disturbances in carbohydrate metabolism [19]. This results in the rapid utilization of glycogen to meet the energy demands under stress conditions and supply energy demands in the form of glucose, as supported from the curve-fitting analysis discussed in Section 3.2. Concentration of carbohydrates was significantly reduced in gills of fish exposed to the fenvalerate concentration. These molecules are structurally relevant and an immediate source of energy for cells [20]. Carbohydrates have been related mainly to an increase in energy demands for detoxification processes to cope with the effects of chemical contaminants [21]. The band at 1400 cm−1 is because of the COO− symmetric chain of vibration of amino acids and fatty acids. The groups 1231 cm−1 and 1084 cm−1 are because of asymmetric and symmetric stretching modes separately to phosphodiester groups in nuclei acids instead of phospholipids [22, 23]. In addition, the contribution of these groups of phosphate residues, which are available in membrane lipids, was insignificant [24]. However, symmetric phosphate stretching may be concealed by the spectral contribution of the glycogen band that manifests at 1010, glucose at 1035 cm−1 and lactic acid at 1134 cm−1. It was uncovered by utilizing curve fitting in the region 1200–900 cm−1 as discussed in Section 3.2.

Fig. 1.

FTIR spectra of gill tissues of Oreochromis mossambicus with control, lower and higher sublethal concentrations of fenvalerate treatment in the region 4000−400 cm−1

Table 1.

Tentative frequency assignment and their functional group of gill tissues of an edible fish Oreochromis mossambicus treated with fenvalerate exposure

| Control | LSL | HSL | Assignments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3297 (m) | 3298 (m) | 3297 (m) | Amide A: NH stretching of proteins |

| 2960 (w) | 2958 (w) | 2957 (m) | CH3 asymmetric stretching of fatty acids |

| 2922 (s) | 2926 (vs) | 2933 (vs) | CH2 asymmetric stretching lipid |

| 2873 (m) | 2871 (m) | 2874 (vw) | CH3 symmetric stretching of mainly proteins |

| 2858 (m) | 2853 (m) | 2851 (m) | CH2 symmetric stretching of mainly lipids |

| 1652 (s) | 1651 (m) | 1652 (w) | Amide I proteins |

| 1541 (m) | 1547 (w) | 1548 (vw) | Amide II |

| 1400 (m) | 1396 (w) | 1402 (vw) | COO− symmetric stretch fatty acids and amino acids |

| 1231 (m) | 1233 (vw) | 1237 (vw) | PO2− asymmetric stretching |

| 1158 (m) | 1159 (vw) | 1156 (vw) | C-O asymmetric stretching of glycogen |

| 1084 (vw) | 1080 (vw) | 1081 (vw) | PO2− symmetric stretching |

vs very strong, s strong, m medium, w weak, vw very weak

Fig. 2.

Normalized band area at 3297 cm−1 with control, lower, and higher sublethal concentrations of fenvalerate treatment in the region 3600−3100 cm−1

Fig. 3.

Normalized band area at 2925 cm−1 with control, lower, and higher sublethal concentrations of fenvalerate treatment in the region 3050−2800 cm−1

Table 2.

Intensity ratios selected bands of gill tissues of an edible fish Oreochromis mossambicus treated with fenvalerate exposure

| Intensity | Significance | Control | LSL | HSL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1545/I3291 | Protein | 0.413 ± 0.024 | 0.293 ± 0.013 | 0.274 ± 0.035 |

| I1545/I1657 | Protein | 0.810 ± 0.036 | 0.519 ± 0.027 | 0.383 ± 0.047 |

| I2924/I2853 | Lipid | 1.476 ± 0.340 | 1.447 ± 0.327 | 1.562 ± 0.482 |

| I1045/I1545 | Carbohydrates | 1.095 ± 0.741 | 0.804 ± 0.382 | 0.433 ± 0.074 |

The values are the mean ± SE for each group (n = 3). The degree of significance was p < 0.05

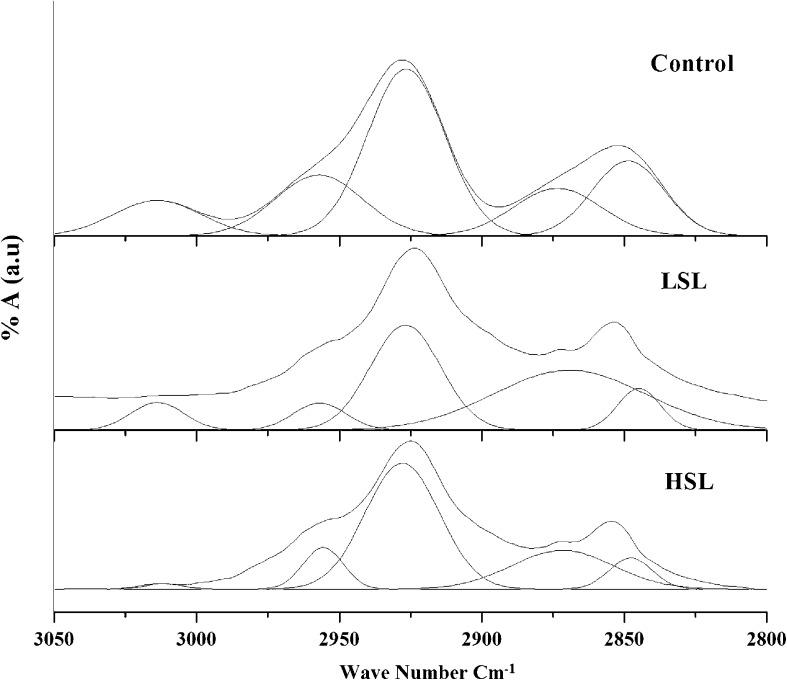

Curve-fitting analysis of fatty acids in the region 3050−2800 cm−1 of Oreochromis mossambicus with control and treated groups

The analysis of the curve fitting in the region 3050−2800 cm−1 shows that the band ~3013 cm−1 is due to the CH stretching mode of HC=CH groups. As seen from Fig. 4, this band decreases, indicating that a population of unsaturated lipids decreased. This change in the band and the shift in the frequency value are presumably the results of a change in lipid metabolism induced by fenvalerate treatment. Another interesting observation is the decrease in the band area of the CH3 asymmetric stretching vibration ~2957 cm−1. This decrease indicates a change in the composition of the acyl chains of lipids due to fenvalerate treatment [25]. The CH2 asymmetric stretching band ~2927 cm−1 and the symmetric CH2 stretching band ~2849 cm−1 provide information about lipid acyl chain flexibility (an order/disorder of lipids) [26]. This change in intensity and the shift in the frequency asymmetric CH2 stretching band indicate a change in lipid disorder in the membranes of tissues [13]. In our study, it is observed from Fig. 4 that the shift in frequency and the intensity changes of CH2 asymmetric decrease in the lower sublethal concentration, indicating decreases in lipid fluidity whereas at higher sublethal treatment it increases. This increase in lipid contents at the higher treatment is due to excessive production of lipids to overcome the increased toxicity. Similar results of increases in the proportions of CH2 groups were observed by FTIR spectroscopy in the case of liver tissues of rainbow trout due to induced estradiol [16].

Fig. 4.

Results of curve-fitting analysis showing lipid changes in control, lower, and higher sublethal concentrations of fenvalerate treatment in the region 3050−2800 cm−1

The changes in the deep interior of the bilayer were monitored by the wave number of the CH3 symmetric stretching mode observed at ~ 2873 cm−1. A decrease in the frequency of the band reflects decreasing liberation freedom of the acyl chains of the phospholipids of the gill tissues of Oreochromis mossambicus. Table 3 shows the band area ratio of the lipids bands that is used for quantitative measurement of changes that occur due to toxicity. The ratio of absorbance for the olefinic group and the sum of absorbance of the CH2 group (CH/asCH2 + sCH2) indicate a degree of lipid saturation in the gill tissues. It shows that the ratio decreases in the case of both LSL and HSL, indicating a decrease in lipid saturation. The ratio of absorption of the methyl and methylene groups CH3/asCH2 + sCH2 shows an increase in value, indicating the absence of a long chain of fatty acids. Further, the ratio of CH2/sCH2 indicates the degree of lipid disorder. The high value indicates lower disorder and lower motional freedom in lipid acyl chains in membranes in gill tissues. Similar results were observed by Emilia Staniszwe et al. [27] in the case of rat organs studied using FTIR spectroscopy.

Table 3.

Ratio of band area measurement of selected bands of gill tissues of Oreochromis mossambicus treated with fenvalerate exposure

| Band area ratio | Control | LSL | HSL |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH3/asCH2+ sCH2 | 0.23 ± 0.06 | 0.98 ± 0.07 | 0.37 ± 0.02 |

| CH/asCH2+ sCH2 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| as CH2/sCH2 | 2.39 ± 0.83 | 4.16 ± 1.03 | 6.96 ± 1.20 |

The values are the mean ± SE for each group (n = 3)

The degree of significance was p < 0.05

Table 4 shows a decrease in the band area of the CH2 symmetric and asymmetric bands as a result of fenvalerate treatment. This decrease demonstrates a change to a lower concentration of saturated lipid content or synthesis of shorter chain lipids in the membranes, which in turn might mean more fluidity [28]. However, at a higher sublethal concentration, CH3 asymmetric stretching increases, which implies the existence of the formation of different domains with different physical properties within the cell membrane. This behavior has been reported in biological membranes [29, 30].

Table 4.

Results of curve-fitting analysis of gill tissues Oreochromis mossambicus treated with fenvalerate exposure expressed as a function of percentage area and their band assignments in 2800–3050 region cm−1

| Assignments | Control | LSL | HSL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave no. | Area (%) | Wave no. | Area (%) | Wave no. | Area (%) | |

| CH2 symmetric stretching/lipids | 2849 | 17.54 ± 1.03 | 2845 | 8.40 ± 0.93 | 2852 | 8.13 ± 0.48 |

| CH3 symmetric stretching/proteins | 2873 | 13.56 ± 0.36 | 2869 | 42.86 ± 1.72 | 2872 | 23.87 ± 1.52 |

| CH2 asymmetric stretching/lipids | 2922 | 41.85 ± 1.93 | 2926 | 34.97 ± 1.38 | 2933 | 56.59 ± 1.73 |

| CH3 asymmetric stretching/lipids | 2957 | 17.22 ± 1.06 | 2957 | 6.79 ± 0.94 | 2956 | 10.05 ± 0.84 |

| Olefinic HC=CH lipids | 3013 | 9.93 ± 0.08 | 3014 | 6.97 ± 0.63 | 3012 | 1.36 ± 0.07 |

The values are the mean ± SE for each group (n = 3). The degree of significance was p < 0.05

Curve-fitting analysis of carbohydrates in the region 1200−900 cm−1 of Oreochromis mossambicus with control and treated groups

The consequences of curve fitting in the region 1200–900 cm −1 demonstrate the presence of glycogen, glucose, and lactic acid at 1010, 1035, and 1134 cm−1 separately. Table 5 shows band area measurements obtained as results of curve-fitting analysis. Carbohydrates are essential and prompt sources of energy in stress conditions. Carbohydrate reserves are depleted to take care of the energy demand. Consumption of glycogen might be because of direct use for energy generation, caused by pesticide stress [31]. As shown in Fig. 5, a noteworthy diminishment in glycogen is observed in treated gill tissues because of fenvalerate treatment. The lactic acid formed, as a by-product, is used for cell functions. It is believed that the lessening in glycogen substance may be because of the restraint of hormones, which adds to glycogen synthesis. A decrease in the glycogen level demonstrates its quick use to meet the improved vitality requests in pesticide-treated animals through glycogen [32]. Umminger [33] hypothesized that glycogen is utilized as the guideline and a quick vitality antecedent in fish under stress conditions. There was a marked diminish in the glycogen in the tissues of fish when presented to the fenvalerate concentration. This might be because of the synthesis of carbohydrates to meet the stress under toxicity. The glycogen splits into glucose by gill tissues under an anaerobic metabolism system to utilize the vitality to meet the stress under toxicants. The impact of the toxicant resulted in the lessening of the energy resource and henceforth there was a general abatement in glycogen amount. Similar results of a decrease in glucose and glycogen levels in fish T. mossambica due to pesticides were reported by Sobha Rani et al. [34].

Table 5.

Results of curve-fitting analysis of gill tissues Oreochromis mossambicus treated with fenvalerate exposure expressed as a function of percentage area and their band assignments in 1200−900 region cm−1

| Assignments | Control | LSL | HSL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave no. | Area (%) | Wave no. | Area (%) | Wave no. | Area (%) | |

| Glycogen | 1010 | 49.89 ± 2.47 | 1011 | 38.72 ± 1.79 | 1015 | 25.64 ± 1.03 |

| Glucose | 1035 | 30.54 ± 0.96 | 1036 | 59.48 ± 2.05 | 1041 | 58.85 ± 1.59 |

| Lactic acid | 1134 | 19.57 ± 1.30 | 1130 | 1.81 ± 0.93 | 1136 | 15.53 ± 0.94 |

The values are the mean ± SE for each group (n = 3). The degree of significance was p < 0.05

Fig. 5.

Results of curve-fitting analysis showing carbohydrate changes in control, lower, and higher sublethal concentrations of fenvalerate treatment in the region 1200−900 cm−1

Fenvalerate uniquely diminishes the whole animal oxygen utilization; the consequent lessening in oxidative metabolism favors anaerobic respiration to take care of the energy demand [35]. It results in changes in hematological parameters and alterations in antioxidant enzymes. We can derive from the present review that the progressive accumulation of fenvalerate in gill target tissues affected the movement of glycogen level. The abatement in lactate dehydrogenase activity with a subsequent increment in the levels of lactic acid proposes the predominance of the anaerobic segment, glycolysis [36]. Shweta Agrahari [37] reported a decrease in oxygen consumption after the introduction of endosulfan and fenvalerate to freshwater fish Clarias batrachus. The present work indicates that fenvalerate causes alterations in the carbohydrate metabolism of the fish Oreochromis mossambicus. Our study has shown a decrease in glycogen values and an inhibition in the activities of carbohydrate moieties. The decrease in glycogen synthesis is also attributed to the inhibition of the enzyme glycogen synthesis that mediates glycogen synthesis. Similar results were reported by [32, 38] on the effect of pesticides on carbohydrate metabolism in various species, indicating an attenuation of the energy reserve of pesticide stress.

Curve-fitting analysis of the protein secondary structure in the region 1700–1600 cm−1 of Oreochromis mossambicus with control and treated groups

Proteins possess a remarkable position in the metabolism of cells, which intervene in different metabolic pathways [39]. A curve-fitting examination was taken in the amide I region (1720−1600 cm−1) to study the secondary structural variation of proteins. As observed from Fig. 6, four peaks occur at 1680, 1657, 1638, and 1618 cm−1. The peak at 1618 cm−1, 1638 cm−1 is because of the β sheet; 1657 cm−1 because of α helix and 1680 cm−1 due to β turn [40, 41]. From Table 6, the percentage area of the α helix declines and the increase in the β sheet structure is due to the modification of existing proteins or synthesis of new proteins. This is consistent with the mechanisms of β sheet formation [42]. Further, the β turn was formed and changes in the secondary structure may be a sign of a change in the existing proteins. This outcome is in agreement with other studies [43, 44].

Fig. 6.

Results of curve-fitting analysis showing changes in the secondary structure of proteins in control, lower, and higher sublethal concentrations of fenvalerate treatment in the amide I region

Table 6.

Results of curve-fitting analysis expressed as a function of percentage areas of protein secondary structures and their band assignments for gill tissues of Oreochromis mossambicus treated with fenvalerate exposure in amide I region

| Control | LSL | HSL | Assignments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave no. | Area (%) | Wave no. | Area (%) | Wave no. | Area (%) | |

| 1618 | 4.785 ± 1.04 | 1617 | 4.632 ± 0.86 | 1621 | 8.26 ± 0.95 | β sheet |

| 1638 | 38.43 ± 1.58 | 1637 | 36.53 ± 1.07 | 1636 | 32.26 ± 1.37 | β sheet |

| 1657 | 49.74 ± 0.79 | 1665 | 47.94 ± 1.53 | 1654 | 23.26 ± 1.32 | α helix |

| 1680 | 9.69 ± 0.74 | 1679 | 8.88 ± 0.75 | 1680 | 16.12 ± 0.95 | β turn |

The values are the mean ± SE for each group (n = 3). The degree of significance was p < 0.05

This shows that the structural conformation of the protein in the gill tissues was significantly impacted by fenvalerate exposure. In the present test, protein values were diminished in the fenvalerate-treated group compared with the control group. Similar results have been reported by various authors [45, 46]. The outcomes reveal that fenvalerate influences changes in the protein secondary structure in Oreochromis mossambicus, prompting the impaired protein metabolism. This secondary structural change results in a decrease in hydrogen bonding of the peptide backbone. Karthikeyan [16] hypothesized that the amide I and II regions shifts result in conformational changes in the existing set of proteins corresponding to the secondary structural protein change. Therefore, this may be a conceivable clarification for the altered protein secondary structure due to toxicity. This changes the protein profile of the β-sheet structure that was studied from FTIR spectra.

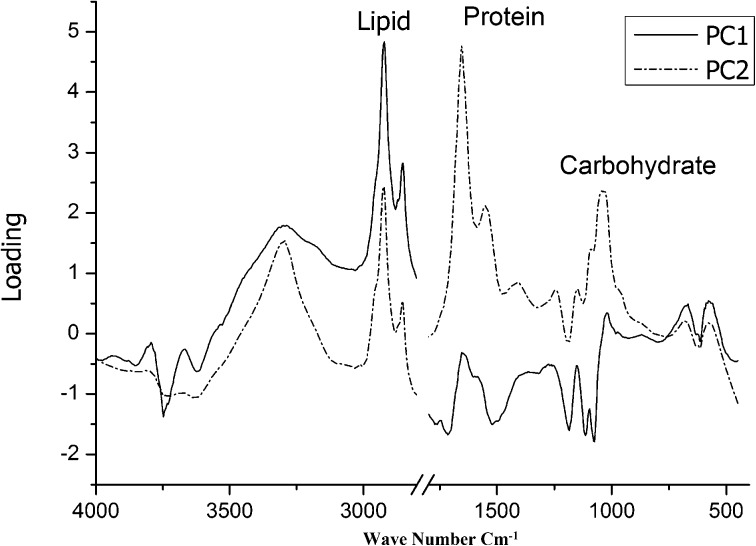

Principal components analysis of biochemical variation in the gill tissue of Oreochromis mossambicus with control and treated groups

Figure 7 shows a PCA score plot obtained using a factor reduction method of the samples studied. The score plot shows the degree of variation in the gill tissues between the samples studied. The results show a distinct variation between control and treated samples. Within the score plots, the nearness of the individual samples to each other suggests a similarity of chemical structures and distance suggests dissimilarity. The highest absolute eigenvalue corresponds to components 1 and 2. The third component is ignored due to least variation and the lowest eigenvalues. The first component accounts for 63% variation and the second component accounts for 31% variation of the samples studied. This loading value of component 2 with the corresponding wave number is plotted in Fig. 8. A high positive index of PCA suggests a prominent change of total biomolecules present in the sample. More importantly, it suggests that these molecules are responsible for the alterations in gill tissues due to pesticide contaminants. From Fig. 8, the most distinguishing wavenumber corresponding to a specific biochemical assignment was visualized following the application of PCA. Figure 8 shows that the lipid has a strong positive loading along PC1, showing the highest variation responsible for the discrimination among the sample studied. This is supported by FTIR spectra - by the variation in the peak position, band area, and frequency shift in the lipid region. Proteins and carbohydrate moieties are the next parameters influencing the changes due to fenvalerate treatment. The results are well supported by the FTIR study using curve fitting analysis made in the selected regions. This parameter is responsible for a distinct variation between control and treated samples. Thus, PCA helps to understand and analyze the variation among the samples of gill tissues of Oreochromis mossambicus with reference to compositions that are supported from the FTIR spectra.

Fig. 7.

PCA plots showing distinct variation of gill tissues of Oreochromis mossambicus of control, lower, and higher sublethal concentrations of fenvalerate treatment

Fig. 8.

Variation of the factor loading obtained from the PCA with the corresponding wave number

Conclusions

To summarize, the biochemical parameters show that fenvalerate instigated hindrance to impairment of body metabolism and resistance. The tested parameters like lipid, proteins, and glycogen variations in gill tissues are utilized as the greatest biomarkers of contamination in the water bodies due to pyrethroids. Additional exploration with toxicity testing techniques in fish will be extremely valuable in surveying the conceivable eco-toxicological chance of assessments of this pesticide. This could be used as a strategy for assessing the effect of contaminants for defining directions and proper administration choices of contaminated water bodies. The use of PCA strategies furthermore helps us to obtain a reasonable picture of distinction among the samples in light of the biochemical compositional organizations. The eigenvector loading obtained from the eventual outcomes of the PCA shows that lipids are the most noticeable in a unique detachment of the composition after the proteins and carbohydrate. It is clear from the IR spectra that both lipid and proteins appear to have a significant impact on the gill tissues of Oreochromis mossambicus. Our results provide evidence in supporting the use of FTIR spectroscopy in biomonitoring of functional groups in the samples. In this way, the utilization of FTIR spectra with the curve-fitting investigation together with PCA examinations serve to represent the chemical compositions and in assessing the biochemical changes in the gill tissues of Oreochromis mossambicus.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank S.A.I.F, I.I.T, Chennai, for help with the recording of the FTIR spectra.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

There are no known conflicts of interest among the authors associated with this work.

We do not require ethical approval for carrying out experiments with fishes in India.

References

- 1.Pimental D, Edwards CA. Pesticides and eco-systems. Biol. Sci. 2002;32:595–600. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh HS, Reddy TV. Effect of copper sulfate on hematology, blood chemistry and hepato-somatic index of an Indian catfish, Heteropneustes fossilis (Bloch), and its recovery. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 1990;20:20–35. doi: 10.1016/0147-6513(90)90043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velmurugan B, Selvanayagam M, Cengiz EI, Unlu E. The effects of fenvalerate on different tissues of freshwater fish Cirrhinus mrigala. J. Environ. Sci. Health B. 2007;42:157–163. doi: 10.1080/03601230601123292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasanthi K, Muralidhara PS, Rajini K. Fenvalerate-induced oxidative damage in rat tissues and its attenuation by dietary sesame oil. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2005;43:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coats JR, Symonik DM, Bradbury SP, Dyer SD, Timson LK, Atchison GJ. Toxicology of synthetic pyrethroids in aquatic organisms: an overview. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1989;8:671–679. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620080805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta AD, Karthikeyan S. Individual and combined toxic effect of nickel and chromium on biochemical constituents in E. coli using FTIR spectroscopy and principal component analysis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016;130:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.APHA . Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Waste Water. 21. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finney DJ. Probit Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1971. p. 333. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toyran N, Zorlu F, Severcan F. Effect of stereo tactic radio surgery on lipids and proteins of normal and hypo fused rat brain homogenates: a Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy study. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2005;81:911–918. doi: 10.1080/09553000600571022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozek NS, Sara Y, Onur R, Severcan F. Low-dose simvastatin induces compositional, structural and dynamical changes in rat skeletal extensor digitorium longus muscle tissue. Biosci. Rep. 2010;30:41–50. doi: 10.1042/BSR20080150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bozkurt O, Severcan M, Severcan F. Diabetes induces compositional structural and functional alteration on rat skeletal soleus muscle revealed by FTIR spectroscopy: a comparative study with EDL muscle. Analyst. 2010;135(12):3110–3119. doi: 10.1039/c0an00542h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozaki Y, Kaneuchi F. Nondestructive analysis of biological materials by ATR/FT-IR spectroscopy. Part II: potential of the ATR method in clinical studies of the internal organs. Appl. Spectrosc. 1989;43:723–725. doi: 10.1366/0003702894202634. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melin AM, Perromat A, Deleris G. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy: a pharmacotoxicologic tool for in vivo monitoring radical aggression. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2001;165:158–165. doi: 10.1139/y00-087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans HW, Hardison WG. Phospholipid, cholesterol, polypeptide and glycoprotein compositions of hepatic endosome subtraction. Biochem. J. 1985;232:33–36. doi: 10.1042/bj2320033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haris PI, Sevecan F. FTIR spectroscopic characterization of protein structure in aqueous and non-aqueous media. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 1999;7:207–221. doi: 10.1016/S1381-1177(99)00030-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karthikeyan S. Effect of heavy metals mixture nickel and chromium on tissue proteins of an edible fish Cirrhinus mrigala using FTIR and ICP-AES study. Romanian J. Biophys. 2014;24(2):109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibarguren M, Lopez DJ, Escriba PV. The effect of natural and synthetic fatty acids on membrane structure, microdomain organization, cellular functions and human health. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1838(6):1518–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan SA, Liu X, Li H, Li J, Zhou P, ur Rehman Z, Rehman UK. Cd2+ and Pb2+ induced structural, functional and compositional changes in the liver and muscle tissue of crucian carp (Carassius auratus gibelio): an FT-IR study. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2017;17:135–143. doi: 10.4194/1303-2712-v17_1_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon LM, Nemcsok J, Boross L. Studies on the effect of paraquate on glycogen mobilization in liver of common carp Cyprinus carpio L. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1983;75C(1):167–169. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(83)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Javed M, Usmani N. Stress response of biomolecules (carbohydrate, protein and lipid profiles) in fish Channa punctatus inhabiting river polluted by thermal power plant effluent. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015;22:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2014.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arzate-Cárdenas MA, Martínez-Jerónimo F. Energy reserve modification in different age groups of Daphnia schoedleri (Anomopoda: Daphniidae) exposed to hexavalent chromium. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012;34:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cakmak G, Togan I, Uguz C, Severcan F, et al. Appl. Spectrosc. 2003;57(7):835–0841. doi: 10.1366/000370203322102933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong PTT, Papavassiliou ED, Rigas B. Phosphodiester stretching bands in the infrared spectra of human tissues and cultured cells. Appl. Spectrosc. 1991;45:1563–1567. doi: 10.1366/0003702914335580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rigas B, Morgello S, Goldman IS, Wong PTT. Human colorectal cancers display abnormal Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:8140–8144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.8140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi H, French SM, Wong PTT. Alteration in hepatic lipids and proteins by chronic ethanol intake a high-pressure Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopic study on alcoholic liver disease in the rat. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1991;15:219–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cakmak G, Togan I, Severcan F. 17β estradiol induced compositional structural and functional changes in rainbow trout liver revealed by FTIR spectroscopy: a comparative study with nonylhenol. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006;77(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staniszewska E, Malek K, Branska M. Rapid approach to analyze biochemical variation in rat organs by ATR FTIR spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014;118:981–986. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2013.09.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kardas M, Gozen AG, Severcan F. FTIR spectroscopy offers hints towards widespread molecular changes in cobalt-acclimated freshwater bacteria. Aquat. Toxicol. 2014;155:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korkmaz F, Severcan F. Effect of progesterone on DPPC membrane: evidence for lateral phase separation and inverse action in lipid dynamics. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;440:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozek NS, Bal IB, Sara Y, Onur R, Severcan F. Structural and functional characterization of simvastatin-induced myotoxicity in different skeletal muscles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1840:406–415. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tilak KS, Wilson raju P, Butchiram MS. Effects of alachlor on biochemical parameters of the freshwater fish, Channa punctatus (Bloch) J. Environ. Biol. 2009;30(3):421–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cappon ID, Nicholas DM. Factors involved in increased protein synthesis in liver microsomes after administration of DDT. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1975;5:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0048-3575(75)90064-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Umminger BL. Physiological studies on supercooled kill fish Fundulus heteroclitus. III: carbohydrate metabolism and survival at sub zero temperature. J. Exp. Zool. 1970;173:159–174. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401730205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shobha rani A, Sudharsan R, Reddy TN, Reddy PVM, Raju TN. Effect of sodium arsenite on glucose and glycogen levels in freshwater teleost fish, Tilapia mossambica. Pollut. Res. 2000;19(1):129–131. [Google Scholar]

- 35.David M, Mushigeri SB, Prasanth MS. Toxicity of fenvalerate to the freshwater fish Labeo rohita (Hamilton) Geobios. 2002;29:25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amacher DE. A toxicologist’s guide to biomarkers of hepatic response. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2002;21(5):253–262. doi: 10.1191/0960327102ht247oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agrahari S, Pandey KC, Gopal K. Biochemical alteration induced by monocrotophos in the blood plasma of fish, Channa punctatus (Bloch) Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2007;88(3):268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2007.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samuel M, Sastry KV. In vivo effect of monocrotophos on the carbohydrate metabolism of the freshwater snakehead fish Channa punctatus. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1989;34:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0048-3575(89)90134-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cox MM, Nelson DL. Lehninger’s Principles of Biochemistry. 5. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1989. pp. 570–572. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furlan PY, Scott SA, Peaslee MH. FTIR STR study of pH effect on egg albumin secondary structure. Spectrosc. Lett. 2007;40:475–482. doi: 10.1080/00387010701295950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karthikeyan S, Easwaran R. Analysis of a curve fitting model in the amide region applied to the muscle tissues of an edible fish: Labeo rohita fingerlings. J. Biol. Phys. Chem. 2013;13:125–130. doi: 10.4024/13KA13A.jbpc.13.04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Creighton TE. Pathway and mechanisms of protein folding. Adv. Biophys. 1984;18:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0065-227X(84)90004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palaniappan PLRM, Renju VB. FT-IR study of the effect of zinc exposure on the biochemical contents of the muscle of Labeo rohita. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2009;52:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.infrared.2008.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palaniappan PLRM, Nishanth T, Renju VB. Bioconcentration of zinc and its effect on the biochemical constituents of the gill tissues of Labeo rohita: an FT-IR study. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2010;53:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.infrared.2009.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nayak AK, Das BK, Kohli MPS, Mukherjee SC. The immunosuppressive effect of a-permethrin on Indian major carp, rohu (Labeo rohita Ham) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2004;16:41–50. doi: 10.1016/S1050-4648(03)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jee JH, Masroor F, Kang JC. Responses of cypermethrin-induced stress in haematological parameters of Korean rockfish, Sebastes schlegeli (Hilgendorf) Aquat. Res. 2005;36(9):898–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01299.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]