Abstract

Next-generation sequencing technology has enabled the comprehensive detection of genomic alterations in human somatic cells, including point mutations, chromosomal rearrangements, and structural variations (SVs). Using sophisticated bioinformatics algorithms, unbiased catalogs of SVs are emerging from thousands of human cancer genomes for the first time. Via careful examination of SV breakpoints at single-nucleotide resolution as well as local DNA copy number changes, diverse patterns of genomic rearrangements are being revealed. These “SV signatures” provide deep insight into the mutational processes that have shaped genome changes in human somatic cells. This review summarizes the characteristics of recently identified complex SVs, including chromothripsis, chromoplexy, microhomology-mediated breakage-induced replication (MMBIR), and others, to provide a holistic snapshot of the current knowledge on genomic rearrangements in somatic cells.

Cancer genomics: cataloging structural variations

Advances in sequencing technologies enable detailed analyses of large genomic alterations, known as structural variations (SV), in human cancer cells. Young Seok Ju and Kijong Yi at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology in Daejeon, review current knowledge on SV patterns in human cancer genomes and the molecular processes through which they arise. In addition to the loss, gain and reshuffling of large nuclear genetic sequences, cancer cells can also acquire external DNA sequences from viruses, mitochondria, or bacteria that alter gene expression levels or affect gene function. Understanding how these SV drive cancer initiation and progression will not only shed light on the organization and function of the genome, but also provide new opportunities for drug discovery and patient screening that will facilitate a more personalized treatment approach.

Introduction

Cancer genomics has contributed to medical oncology by providing the genomic landscape and catalog of somatic mutations of human cancers. This information holds clinically actionable targets that may be used for personalized oncology and the development of new therapeutics. In addition, because the catalog of somatic mutations is a cumulative archeological record of all the mutational processes a cancer cell has experienced throughout the lifetime of a patient, it provides a rich source of information for biologists to understand the DNA damage and repair mechanisms that function in human somatic cells1.

Genomic alterations in cancer cells consist of two major categories: (1) small variations that include single-nucleotide variants and short indels, and (2) large variations known as chromosomal rearrangements or structural variations (SVs). SVs are rearrangements of large DNA segments (for example, chromosomal translocations), occasionally accompanying DNA copy number alterations. Although there is no rule that clearly distinguishes the “small” and “large” variation categories, researchers currently regard 50 bp as the tentative cutoff criteria2. Before the era of whole-genome sequencing (WGS), tentatively regarded as prior to 2010, the comprehensive detection of SV “breakpoints” (qualitative changes) was not feasible in cancer genomes. CNAs (quantitative changes) were relatively easier to assess using classical technologies, such as comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) and genotyping microarrays3.

Because high-throughput DNA sequencing technologies produce unbiased sequences from whole genomes within a reasonable timeframe and at a reasonable cost (i.e., < 2000 USD and < 1 week for the production of 30 × WGS data from a tumor and paired normal tissue, as of Nov 2017), many research groups, in particular, two large international consortia (The International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)), have produced large-scale WGS data sets from a variety of common and rare tumor types during the last decade4,5. Various computational algorithms and tools have been developed for the sensitive and precise detection of SVs from the WGS data (reviewed in ref. 6,7). These efforts have enabled the identification of driver SV events with remarkable functional consequences8–14 and mechanistic patterns of SVs, which could not be identified by classical technologies. For example, the chromothripsis15 mechanism, exhibiting a massive number of localized SV breakpoints with extensive oscillation of two DNA copy number states, was observed in cancer genome sequences, and elucidation of its molecular mechanisms followed16–20. However, many features remain unexplored, such as the frequency, activating conditions, and molecular machineries that are associated with the complex event. Understanding the diverse patterns of SVs observed in genome sequences is the first step to answering these questions.

Historical overview of SVs in cancers: from cytogenetics to array CGH

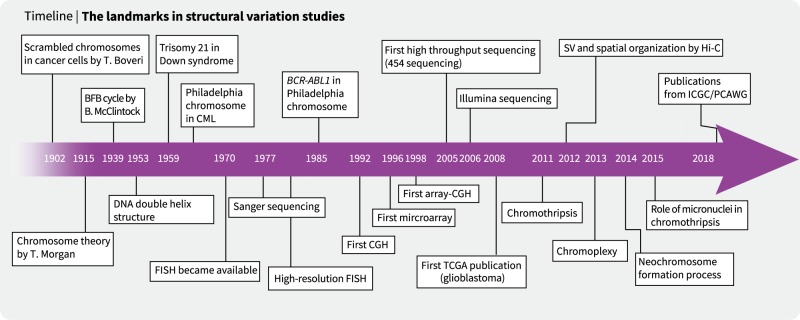

The first insights into SVs in cancer cells were provided by Theodor Boveri in the early twentieth century21 (Fig. 1). By examining dividing cancer cells under a microscope, he observed the presence of scrambled chromosomes associated with uncontrolled cell division. Following the discovery of the double helix DNA structure (1952)22, abnormalities of the genome were proposed to cause many human diseases. For example, the trisomy of chromosome 21 in Down syndrome (1959)23 and the recurrent translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 (known as the Philadelphia chromosome; 1960) in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) were found using cytogenetics technologies24. As the resolution of florescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technology improved, the CML-causing BCR-ABL1 fusion gene in the Philadelphia chromosome was identified25. In parallel, quantitative FISH analyses showed that some genetic loci are markedly amplified from the normal two copies in cancer cells26,27. Further technical improvements, such as CGH28, array CGH29 and genotyping microarray30,31, enabled genome-wide screening of CNAs in the 1990s and 2000s27,28,32,33. Many cancer genes have been found to be frequently amplified (i.e., MCL1, EGFR, MYC, and ERBB2) or deleted (i.e., CDKN2A/B, RB1, and PTEN) in cancer cells34,35. Indeed, genomic instability is one of the hallmarks of cancers36,37.

Fig. 1.

The history of structural variation research

Advances in hybridization technologies increased the resolution of CNA detection to ~ 1000 base pairs. However, regardless of the resolution, these methods only approximate the genomic locations of CNAs without giving an accurate determination of the breakpoint sequences. Moreover, detection of novel copy number-neutral SVs (for example, balanced inversions and translocations) is fundamentally impossible when using array technologies. In addition, hybridization technologies are not adequate for exploring repetitive genome sequences (i.e., transposable elements)3. In the 2010s, advances in sequencing technologies finally enabled comprehensive, fine-scaled SV detection4,38,39.

Patterns and mechanisms of SVs

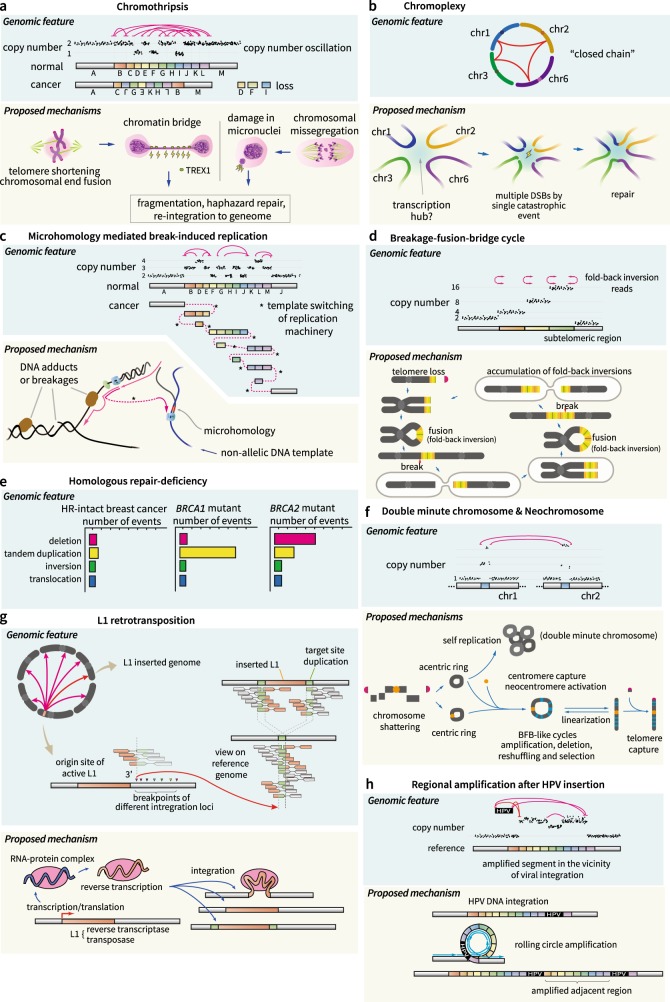

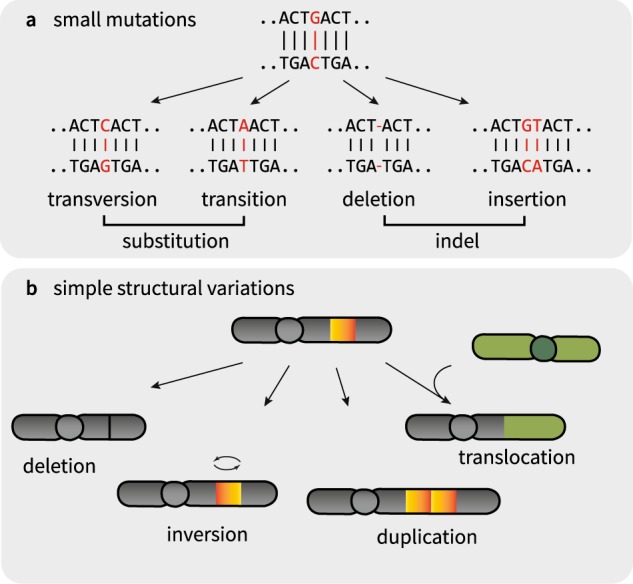

Conventionally, cytogenetic technologies categorized SVs into four simple types: (large) deletions, duplications (amplifications), translocations, and inversions (Fig. 2). By definition, deletions and duplications are accompanied by CNAs. By contrast, inversions and translocations can be copy number neutral (balanced inversion or translocation). However, whole-genome analysis has shown that many SVs are not independent events but are acquired by a “single-hit” event and are therefore complex genome rearrangements. In this section, we introduce typical patterns of complex rearrangements found in cancers.

Fig. 2. Types of basic genomic variations.

a Small mutations, base substitution and indels. b Simple structural variations, deletion, amplification, inversion, and interchromosomal translocation

Chromothripsis

Chromothripsis is a pattern of complex chromosomal rearrangement that is affected by a massive number of SV breakpoints, sometimes > 100, which are densely clustered in mostly one or a few chromosomal arms40 (Fig. 3a). The term chromothripsis means “chromosome shattering into pieces” and was identified in 201115. In general, chromothripsis is found in ~ 3% of all tumors and is frequently found in bone tumors (osteosarcoma and chordoma; 25%) and brain tumors (10%)15. However, an accurate description of its prevalence and cancer type specificity remains largely elusive.

Fig. 3. Patterns and proposed mechanisms of structural variations.

a Chromothripsis, showing a shattering and subsequent repair process. Telomere crisis and/or micronuclei by chromosome mis-segregation may induce chromothripsis. b Chromoplexy, showing a “closed chain” (upper) in the Circos plot. This is a multi-chromosomal translocation (lower). c MMBIR by template switching of the replication machineries. d BFB cycle, showing subtelomeric copy number increases and fold-back inversions. Proposed mechanisms are shown below. e Different patterns of SVs in BRCA1- and BRCA2-mutant breast cancers. f Patterns and formation of DMs and neochromosomes. DNA fragments can self-ligate, forming a ring structure, and are amplified (DMs). Fragments capturing centromeres and telomeres become neochromosomes. g Patterns and processes of L1 retrotransposition in the cancer genome. h HPV integration and regional rolling-circle amplification

In the typical case of chromothripsis localized in a chromosome arm, a massive number of SV elements (breakpoints) consist of similar proportions of all intrachromosomal rearrangement types (i.e., deletion type, tandem duplication type, and head-to-head and tail-to-tail inversion types). The copy number of the involved chromosome arm usually oscillates between the normal and deleted copy number states. In addition, loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) is frequently observed in the low-DNA copy number regions. The simplest model for explaining the chromothripsis pattern is that a single “catastrophic hit” shatters one or a few chromosome arms into hundreds of DNA segments simultaneously in an ancestral region of cancer cells, and DNA repair pathways (presumably non-homologous end-joining) reassemble the fragments in an incorrect order and orientation15. DNA segments that are not rejoined during the repair process result in deletions. Although such a scenario explains the features of chromothripsis, the nature of the catastrophic hit is not fully understood. At present, two non-mutually exclusive mechanisms have been experimentally shown: (1) telomere crisis with telomere shortening and end-to-end chromosomal fusions followed by the formation of a chromatin bridge41, and (2) micronuclei formation due to mis-segregated chromosomes during mitosis18.

A telomere is the DNA sequence region at the end of a chromosome that protects the chromosome. When telomeres are shortened, the ends of chromosomes (chromatids) can be fused, forming a dicentric chromosome that fails to segregate into daughter cells during mitosis. The fused sites are then stretched during the anaphase of mitosis41, forming a chromatin bridge. Under certain circumstances, the bridge induces a partial rupture of the nuclear membrane in anaphase, and the nuclease activity of the 3′ repair exonuclease 1 (TREX1) generates extensive single-strand DNA and bridge breakage42. The frequently observed SV spectrums in the daughter cells are genomic rearrangements recapitulating known features of chromothripsis combined with localized hyper-point mutations (kataegis)42. This mechanism explains why chromothripsis frequently occurs in the vicinity of telomeric regions.

Alternatively, a physical isolation of chromosomes in aberrant nuclear structures (micronuclei) was proposed as a possible mechanism of chromothripsis18,19. Micronuclei are frequently caused by errors in cell division, such as mis-segregation of intact chromosomes during mitosis43 and acentric genome fragments from abnormal DNA replication/repair processes19,20,44. Molecular processes in micronuclei are known to be error prone; thus, isolated genetic materials are massively broken into pieces and reassembled18,19,45. The rejoined DNA fragments, showing chromothripsis-like features, can be fixed in a daughter cell.

Chromoplexy

Chromoplexy is another pattern of complex rearrangements that has many interdependent SV breakpoints (mostly interchromosomal translocations) but usually fewer than chromothripsis. This phenomenon was identified in prostate cancer genomes46. Chromoplexy mechanisms frequently disrupt tumor suppressor genes (i.e., PTEN, TP53, and CHEK2) and activate oncogenes by the formation of fusion genes (i.e., TMPRSS2-ERG) in the cancer type. The prevalence in prostate cancer is ~ 90%, but chromoplexy has not yet been explored in other cancer types. Conceptually, chromoplexy is an extended version of balanced translocation that reshuffles multiple chromosomes (rather than two chromosomes, as in balanced translocations) in a new scrambled configuration (Fig. 3b). Therefore, SVs in a chromoplexy event usually involve multiple chromosomes (usually > 3), and its rearrangement pattern resembles a “closed chain”. Although small deletions can occasionally be combined in the vicinity of the breakpoints as a form of “deletion bridge”, a large fraction of SVs in a chromoplexy event is copy number neutral. Like chromothripsis, chromoplexy is readily explained by the presence of a catastrophic hit that produces multiple DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). Unlike chromothripsis, multiple DSBs in chromoplexy are not confined to a chromosome arm but are rather distributed across many chromosomes46.

Although the phenomenon is found in many common cancers (including prostate cancers, non-small cell lung cancers, head and neck cancers, and melanomas46) and rare solid cancers47, the molecular basis of the catastrophic hit is unclear. The genome-wide distribution of DSBs in a chromoplexy event is not random but is enriched in actively transcribed and open chromatin regions48–50. This suggests that a nuclear transcription hub wherein many co-regulated genomic regions are spatially aggregated is fragmented by the catastrophic blow in chromoplexy46.

Microhomology-mediated break-induced replication

The basic mechanisms of chromothripsis and chromoplexy are massive “shatter-and-stitch” processes of the genome. In these mechanisms, copy number gains of DNA segments are rarely observed. Cancer genomes frequently harbor another pattern of complex rearrangements, demonstrating a massive number of interspersed copy number gains (amplifications) of one parental allele without evidence of LOH These amplicons are directly interconnected with frequent templated insertions and common microhomologies (2–15 bps) at breakpoint junctions. These features suggest a replication-based mechanism for the acquisition of extra DNA copies, with frequent template switching of the DNA replication complex for the rearrangement (Fig. 3c). The replication-based model, termed microhomology-mediated break-induced replication (MMBIR), was initially suggested to explain the patterns of germline CNAs51,52. Presumably, translesion DNA polymerases, such as Polζ and Rev1, are responsible for MMBIR53.

The cellular conditions that induce MMBIR are not fully understood. Presumably, collapse of a replication fork due to a single-strand DNA break and/or a bulky DNA adduct in the template DNA (collectively referred to as replication stress) interferes with normal DNA replication and stimulates template switching54,55. Normally, the template switching contributes to the repair of broken replication forks using a sister chromatid. However, the process is a double-edged sword that may lead to chromosomal rearrangements when non-allelic chromosomal regions are selected as the template. A lack of Rec/RAD proteins (e.g., RAD51) due to persistent replication stress has been reported to trigger MMBIR51,56.

Breakage-fusion-bridge cycle

The breakage-fusion-bridge (BFB) cycle, first discovered by Barbara McClintock57 in 1939, is a recursive cycle of generation of the dicentric chromosome by telomere fusions and breaks when the two centromeres are pulled apart in anaphase (Fig. 3d). As multiple DSBs occur in random positions in the middle of the two centromeres over a few cell cycles, the BFB cycle leaves typical patterns of rearrangements, including (1) the stair-like increase in subtelomeric regions58 (reviewed in ref. 41) and (2) the enrichment fold-back inversions in the breakpoints. BFB cycle-mediated SVs have been well demonstrated in a subtype of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, which exhibits intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21 involving RUNX1 gene alteration59,60.

Homologous recombination repair defect

Homologous recombination (HR) is a basic cellular mechanism to repair DSBs using identical or similar DNA sequences61. The basic steps of HR are (1) resection of the 5′ extremes of DSBs, (2) invasion of overhanging 3′ ends to a similar or identical DNA segment, and (3) DNA repair using one of two pathways—double-Holliday junction (reviewed in ref. 62) or synthesis-dependent strand annealing (reviewed in ref. 62,63).

The defect of HR (for example, BRCA1 and BRCA2 inactivation) causes genomic instability and increases the incidence of breast and ovarian cancers64,65. Complete inactivation of BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 genes are found in 7% of all breast cancers66, with an enrichment in the triple-negative breast cancer subtype67. BRCA gene-mutant breast cancers have a much higher burden of genome-wide SVs compared to ordinary breast cancers68. Interestingly, specific patterns of SVs are found according to the inactivated genes (Fig. 3e). For example, BRCA1-inactive cancers dominantly harbor short (< 10 kb) tandem duplications, but BRCA2-mutant cancers primarily show deletions68. Generally, BRCA1 recognizes DNA double-strand breaks along with ATM, TP53, and CHEK2 in the HR pathway. BRCA2 has an important role in the loading of RAD5169,70, which is necessary for strand invasion after 5′-end resection71.

The HR defect has been of interest in clinical research fields because HR-defective cancers are susceptible to targeted therapies (PARP inhibitors) that inhibit the base excision repair pathway. This strategy aims to trigger additional genomic instability in HR-defective cancer cells (but not in normal cells), which leads to cancer cell death72. Breast cancer patients with germline BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations are responding well to PARP inhibitor therapy73,74.

Double-minute chromosome and neochromosome

Double-minute chromosomes (DMs) are aberrant genomic segments in a small circular form that are self-replicable but lack a centromere (Fig. 3f). DMs are often massively amplified in various solid and hematologic cancer cells75. DMs are detected in ~ 40% of glioblastomas, and some oncogenes, such as CDK4, MDM2, and EGFR, are frequently co-amplified in DMs76,77. DMs are important in tumorigenesis and tumor clonal evolution78,79. DM segments can be derived from DNA fragments that fail to be reassembled during chromothripsis15.

Neochromosomes are aberrant genomic segments in either circular or linear forms. Unlike DMs, neochromosomes harbor a centromeric structure and (if linear)`telomeric regions (Fig. 3f). Neochromosomes are observed in ~ 3% of all cancers and are especially frequent in a subset of mesenchymal tumors, including parosteal osteosarcomas (90%), atypical lipomatous tumors (85%), dedifferentiated liposarcomas (82%), and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (67%)80. The formation process of neochromosomes has been elucidated in detail from liposarcoma genomes81. Like DMs, neochromosomes begin as circular DNA structures. The intermediate structures subsequently capture centromeres and are finally linearized by the acquisition of telomeres at both ends due to concurrent rearrangements, including chromothripsis- and BFB cycle-like processes.

Transposition of mobile elements

Transposable elements (TEs) are repetitive DNA sequences that occupy 45% of the human genome82. In the human genome, these elements are successful parasitic units that have important roles in genome evolution by generating SVs via “cutting-and-pasting” (DNA transposons) or “copying-and-pasting” themselves (retrotransposons)83. Most of the TEs in human genomes are now truncated and inactive in both germline and somatic lineages. For example, of the 500,000 copies of the L1 retrotransposons84,85 in the human genome, only ~ 100 L1 copies have intact open reading frames and are potentially capable of retrotransposition. In cancer cells, retrotranspositions of L1 are frequently observed (Fig. 3g)86,87 in ~ 50% of pan-cancer tissues86,88, with a high enrichment in esophageal cancers (> 90%), colon cancers (> 90%) and squamous cell lung cancers (> 90%)86,88. L1 retrotransposition is carried out by transcription, processing, reverse transcription, and novel insertion89. In some cases, hundreds of somatic retrotranspositions are observed in a cancer cell. In addition, L1 retrotranspositions occasionally carry adjacent non-repetitive DNA sequences (termed transduction), which can widely scatter genes, exons and regulatory elements across the genome86. The functional impacts of retrotranspositions in the pathogenesis of cancers are emerging90. The retrotranspositional insertion sites are enriched in the heterochromatin and hypomethylated regions91, and cancer-related genes are sometimes affected87,90,92–94.

Insertion of external DNA sequences

In addition to reshuffling of the nuclear genomes mentioned above, cancer cells may acquire completely new extranuclear DNA sequences from viruses, mitochondria95,96 and bacteria97,98. For example, the vast majority of uterine cervical cancers (> 95%) and a substantial fraction of head and neck cancers (12%) contain human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA sequences in their genome99. HPV genome integration is involved in direct tumorigenesis (i.e., inhibition of the p53 pathway by the HPV oncoprotein E6100) and in the induction of genomic instability101. For example, the insertional sites of HPV are frequently amplified102 by the “loop-mediated mechanism”101 (Fig. 3h). If brief, the insertional regions tend to form a loop structure, which is susceptible to amplification during DNA replication. As a result, genomic DNA segments flanked by viral insertions can be massively amplified, occasionally by > 50 copies, which leads upregulation of the viral oncoprotein and co-amplified adjacent gene products101.

Intracellular nuclear transfers of full or partial mitochondrial DNA sequences are also observed in cancer genomes95,103–105. The prevalence of this event is ~ 2% of all cancers, with an enrichment in skin, lung, and breast cancers96. However, the molecular mechanism by which mitochondrial DNA is mobilized and inserted into nuclear genomes has not been fully elucidated. Most somatic nuclear integrations of mitochondrial DNA do not occur alone but are frequently combined with other complex rearrangements, suggesting that mitochondrial DNA fragments could be used as a “filler material” or a string for weaving broken nuclear DNA segments into the DNA repair processes in somatic cells106.

Comprehensive signatures of SVs

Beyond the rearrangement patterns mentioned above, additional mechanisms presumably remain undetermined. Many ongoing efforts are being carried out to reveal comprehensive SV mutational signatures in cancer genomes. For example, > 30 mutational signatures have been revealed for point mutations from the statistical analysis of large catalogs of mutations107. Similar concepts have been applied to SVs in breast cancer genomes by clustering genome-wide SVs according to their features, such as local proximities, rearrangement class (tandem duplication, deletion, inversion, and translocation), and rearrangement size68. The analysis yielded six rearrangement signatures: (1) large ( > 100 kb) tandem duplication, (2) dispersed translocation, (3) small tandem duplication, (4) clustered translocation, (5) deletion, and (6) other clustered rearrangements. Among these signatures, tandem duplications (SV signatures 1 and 3) are thought to occur due to HR deficiency108. In a similar manner, Li et al.109 identified nine SV signatures from a cohort of > 2500 cancer genomes. Using this classification, they inferred that a considerable proportion of rearrangements are caused by replication-based mechanisms.

Large-scale genome studies have revealed that SVs are not evenly distributed across the genome. The density of SVs is affected by local genome and epigenome features as well as by 3D genome conformation110–112. For example, local rearrangement rates are affected by replication time, transcription rate, GC content, methylation status113,114, and chromosomal fragile sites115,116, including chromosome loop anchor sites117. More systematic analyses combining genome and epigenome features from a larger cohort will likely yield a better definition of the structural variation signatures and additional mutational processes in human cancers.

Functional consequences of SVs

SVs have functional consequences in tumorigenesis and clonal evolution via at least four direct mechanisms (Table 1): (1) truncation of genes (for example, deletion or gene disruption)8,118, (2) amplifications of whole genes and their expression levels by the “dosage effect”, (3) fusion gene formation (for example, BCR-ABL in CML and EML4-ALK in lung cancers) and (4) mobilization of gene-regulatory element organization (‘enhancer hijacking’)2. The first three mechanisms are conventional, and evidence for the fourth mechanism is actively emerging. Examples of enhancer hijacking, which alters gene expression of cancer genes, including IRS4, SMARCA1, and TERT, have been reported119. In breast cancers, breast tissue-specific regulatory regions are recurrently duplicated120, suggesting that positive selection pressures are strongly present. Similarly, many non-coding SVs may affect the gene expression of adjacent or distant genes by mobilizing many regulator regions or expressional quantitative trait loci121,122. More specifically, an experiment has shown that rearrangement involving the genomic topologically associating domain boundary can alter gene expression by altering the 3D genome structures that are involved in regulating gene expression123.

Table 1.

Selected examples of genes altered by structural variation in cancers

| Type | Malignancy | Affected gene (prevalence) |

|---|---|---|

| Deletion | Retinoblastoma | RB (~ 100%)131 |

| Renal cell carcinoma | VHL (90% of clear cell type) | |

| Amplification | Invasive breast carcinoma | ERBB2 (18–25%) |

| Neuroblastoma | MYCN (20–25%) | |

| Diffuse large B cell lymphoma | BCL2 (31%) | |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | MLL, ALL1 (5–10%) | |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma | FGF4 (7%) | |

| Fusion gene | Lung adenocarcinoma | ALK (3.5%) |

| Prostatic adenocarcinoma | TMPRSS2-ETS family (29–43%) | |

| Chronic myelogenous leukemia | ABL-BCR (~ 100%) | |

| Burkitt lymphoma | MYC-IGH (~ 100%) | |

| Ewing Sarcoma | EWSR1-FLI1 (~ 100%) | |

| Enhancer hijacking | Medulloblastoma | GFI1 family gene activation132 |

| Salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma | MYB gene overexpression133 | |

| T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma | TAL1 overexpression (30%)134,135 | |

| Lung squamous cell carcinoma | IRS4 overexpression119 |

Future direction and conclusion

The revolution of WGS provides an unbiased and comprehensive catalog of SVs in human cancer cells. Via a systematic, in-depth analysis of SV breakpoints, unique patterns and their underlying mutational processes are now emerging. However, current predominant WGS platforms producing short reads (< 500 bp) provide disintegrated data that are limited in the direct phasing of SV breakpoints. Despite many bioinformatic and statistical algorithms, the seamless reconstruction of final reassembled chromosomes is sometimes impossible with short read sequences, especially when the SVs are highly complex. In addition, SVs involved in highly repetitive regions (for example, telomeres, centromeres, and simple repeats) cannot be fully explored using these technologies. To this end, the combination of long read sequences (for example, from the PacBio platform) and high-resolution cytogenetics data will be helpful. Alternatively, Hi-C can be used to detect SVs in a high-throughput manner124, although the cost efficiency could be an issue. If culturing somatic cells in vitro is possible, the Strand-seq125 technique can provide fully phased data even if the subjects are not diploid. Single-cell genome sequencing is also a promising technology. For example, single-cell whole-genome sequencing could determine the exact timing of an SV per cell cycle126.

Apart from the technical limitations of DNA sequencing, the accurate molecular mechanisms of SVs are difficult to elucidate because tissue sequencing primarily reflects only the terminal results of SVs. Although we can observe DSBs under a microscope127 or with special sequencing technology (e.g., END-seq128), observing the DSBs and final rearrangements (outcome) at the sequence level in the same cell is currently impossible to. Well-designed experiments and analyses are needed to bridge this gap.

Understanding the functional consequences of SVs and their association with drug efficacy are important for precision medicine. For accurate functional analyses, the “genome sequencing-only” approach is limited, and the integration of multiomics data, such as genome, transcriptome, and epigenome data, are needed. Data representing the association between gene expression and the variation in the genome are being collected in the GTEx project121. Information on the regulatory region of the genome and the genomic regions interacting with it is actively accumulating in the ENCODE129 and FANTOM projects130,131. By integrating these data sets, we will be able to comprehensively interpret the functional consequences of genome SVs and further advance precision oncology in the near future.

Acknowledgements

We thank Joonoh Lim for the comments on the manuscript. This project was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D Project via the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), which was funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare of Korea (HI16C2387).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458:719–724. doi: 10.1038/nature07943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carvalho CMB, Lupski JR. Mechanisms underlying structural variant formation in genomic disorders. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016;17:224–238. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2015.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trask BJ. Human cytogenetics: 46 chromosomes, 46 years and counting. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:769–778. doi: 10.1038/nrg905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joly Y, Dove ES, Knoppers BM, Bobrow M, Chalmers D. Data sharing in the post-genomic world: the experience of the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) Data Access Compliance Office (DACO) PLoS. Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan P, Sung WK. Structural variation detection using next-generation sequencing data: a comparative technical review. Methods. 2016;102:36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tattini L, D’Aurizio R, Magi A. Detection of genomic structural variants from next-generation sequencing data. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2015;3:92. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2015.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stransky N, Cerami E, Schalm S, Kim JL, Lengauer C. The landscape of kinase fusions in cancer. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4846. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris SW, et al. Fusion of a kinase gene, ALK, to a nucleolar protein gene, NPM, in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Science. 1994;263:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.8122112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi K, et al. KIF5B-ALK, a novel fusion oncokinase identified by an immunohistochemistry-based diagnostic system for ALK-positive lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:3143–3149. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker BC, Zhang W. Fusion genes in solid tumors: an emerging target for cancer diagnosis and treatment. Chin. J. Cancer. 2013;32:594–603. doi: 10.5732/cjc.013.10178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uguen A, De Braekeleer M. ROS1 fusions in cancer: a review. Future Oncol. 2016;12:1911–1928. doi: 10.2217/fon-2016-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar-Sinha C, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Chinnaiyan AM. Landscape of gene fusions in epithelial cancers: seq and ye shall find. Genome Med. 2015;7:129. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0252-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ju YS, et al. A transforming KIF5B and RET gene fusion in lung adenocarcinoma revealed from whole-genome and transcriptome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22:436–445. doi: 10.1101/gr.133645.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephens PJ, et al. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell. 2011;144:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kloosterman WP, et al. Constitutional chromothripsis rearrangements involve clustered double-stranded DNA breaks and nonhomologous repair mechanisms. Cell Rep. 2012;1:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malhotra A, et al. Breakpoint profiling of 64 cancer genomes reveals numerous complex rearrangements spawned by homology-independent mechanisms. Genome Res. 2013;23:762–776. doi: 10.1101/gr.143677.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang CZ, et al. Chromothripsis from DNA damage in micronuclei. Nature. 2015;522:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature14493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crasta K, et al. DNA breaks and chromosome pulverization from errors in mitosis. Nature. 2012;482:53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature10802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffelder DR, et al. Resolution of anaphase bridges in cancer cells. Chromosoma. 2004;112:389–397. doi: 10.1007/s00412-004-0284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boveri T. Concerning the origin of malignant tumours by Theodor Boveri. Translated and annotated by Henry Harris. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:1–84. doi: 10.1242/jcs.025742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson JD, Crick FH. Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature. 1953;171:737–738. doi: 10.1038/171737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lejeune J, Gautier M, Turpin R. [Study of somatic chromosomes from 9 mongoloid children] C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 1959;248:1721–1722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nowell PC, Hungerford DA. Chromosome studies on normal and leukemic human leukocytes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1960;25:85–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heisterkamp N, Stam K, Groffen J, de Klein A, Grosveld G. Structural organization of the bcr gene and its role in the Ph’ translocation. Nature. 1985;315:758–761. doi: 10.1038/315758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung VG, et al. Integration of cytogenetic landmarks into the draft sequence of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:953–958. doi: 10.1038/35057192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sebat J, et al. Large-scale copy number polymorphism in the human genome. Science. 2004;305:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.1098918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kallioniemi A, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization for molecular cytogenetic analysis of solid tumors. Science. 1992;258:818–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1359641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinkel D, et al. High resolution analysis of DNA copy number variation using comparative genomic hybridization to microarrays. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:207–211. doi: 10.1038/2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chee M, et al. Accessing genetic information with high-density DNA arrays. Science. 1996;274:610–614. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hacia JG, Brody LC, Chee MS, Fodor SP, Collins FS. Detection of heterozygous mutations in BRCA1 using high density oligonucleotide arrays and two-colour fluorescence analysis. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:441–447. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iafrate AJ, et al. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:949–951. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Redon R, et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature. 2006;444:444–454. doi: 10.1038/nature05329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beroukhim R, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheble VJ, et al. ERG rearrangement is specific to prostate cancer and does not occur in any other common tumor. Mod. Pathol. 2010;23:1061–1067. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Negrini S, Gorgoulis VG, Halazonetis TD. Genomic instability--an evolving hallmark of cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:220–228. doi: 10.1038/nrm2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Consortium GenomesProject, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JI, et al. A highly annotated whole-genome sequence of a Korean individual. Nature. 2009;460:1011–1015. doi: 10.1038/nature08211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korbel JO, Campbell PJ. Criteria for inference of chromothripsis in cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;152:1226–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maciejowski J, de Lange T. Telomeres in cancer: tumour suppression and genome instability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:175–186. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maciejowski J, Li Y, Bosco N, Campbell PJ, de Lange T. Chromothripsis and kataegis induced by telomere crisis. Cell. 2015;163:1641–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Janssen A, van der Burg M, Szuhai K, GJPL Kops, Medema RH. Chromosome segregation errors as a cause of DNA damage and structural chromosome aberrations. Science. 2011;333:1895–1898. doi: 10.1126/science.1210214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terradas M, Martín M, Tusell L, Genescà A. Genetic activities in micronuclei: is the DNA entrapped in micronuclei lost for the cell? Mutat. Res. 2010;705:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hatch EM, Fischer AH, Deerinck TJ, Hetzer MW. Catastrophic nuclear envelope collapse in cancer cell micronuclei. Cell. 2013;154:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baca SC, et al. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;153:666–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JK, et al. Complex chromosomal rearrangements by single catastrophic pathogenesis in NUT midline carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2017;28:890–897. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marnef A, Cohen S, Legube G. Transcription-coupled DNA double-strand break repair: active genes need special care. J. Mol. Biol. 2017;429:1277–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sima J, Gilbert DM. Complex correlations: replication timing and mutational landscapes during cancer and genome evolution. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2014;25:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiarle R, et al. Genome-wide translocation sequencing reveals mechanisms of chromosome breaks and rearrangements in B cells. Cell. 2011;147:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hastings PJ, Ira G, Lupski JR. A microhomology-mediated break-induced replication model for the origin of human copy number variation. PLoS. Genet. 2009;5:e1000327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu P, et al. Chromosome catastrophes involve replication mechanisms generating complex genomic rearrangements. Cell. 2011;146:889–903. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sakofsky CJ, et al. Translesion polymerases drive microhomology-mediated break-induced replication leading to complex chromosomal rearrangements. Mol. Cell. 2015;60:860–872. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeman MK, Cimprich KA. Causes and consequences of replication stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:2–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Minca EC, Kowalski D. Replication fork stalling by bulky DNA damage: localization at active origins and checkpoint modulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:2610–2623. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sakofsky CJ, Ayyar S, Malkova A. Break-induced replication and genome stability. Biomolecules. 2012;2:483–504. doi: 10.3390/biom2040483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McClintock B. The behavior in successive nuclear divisions of a chromosome broken at meiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1939;25:405–416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.25.8.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greenman CD, Cooke SL, Marshall J, Stratton MR, Campbell PJ. Modeling the evolution space of breakage fusion bridge cycles with a stochastic folding process. J. Math. Biol. 2016;72:47–86. doi: 10.1007/s00285-015-0875-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robinson HM, Harrison CJ, Moorman AV, Chudoba I, Strefford JC. Intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21 (iAMP21) may arise from a breakage-fusion-bridge cycle. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:318–326. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Y, et al. Constitutional and somatic rearrangement of chromosome 21 in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2014;508:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature13115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weiner A, Zauberman N, Minsky A. Recombinational DNA repair in a cellular context: a search for the homology search. Nat. Rev. Micro. 2009;7:748–755. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hastings PJ, Lupski JR, Rosenberg SM, Ira G. Mechanisms of change in gene copy number. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:551–564. doi: 10.1038/nrg2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sekelsky J. DNA repair in drosophila: mutagens, models, and missing genes. Genetics. 2017;205:471–490. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.186759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Friedman LS, et al. Confirmation of BRCA1 by analysis of germline mutations linked to breast and ovarian cancer in ten families. Nat. Genet. 1994;8:399–404. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wooster R, et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995;378:789–792. doi: 10.1038/378789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Antoniou A, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case Series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:1117–1130. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sharma P, et al. Germline BRCA mutation evaluation in a prospective triple-negative breast cancer registry: implications for hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer syndrome testing. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014;145:707–714. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2980-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nik-Zainal S, et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature. 2016;534:47–54. doi: 10.1038/nature17676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shinohara A, Ogawa H, Ogawa T. Rad51 protein involved in repair and recombination in S. cerevisiae is a RecA-like protein. Cell. 1992;69:457–470. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90447-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sung P. Catalysis of ATP-dependent homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange by yeast RAD51 protein. Science. 1994;265:1241–1243. doi: 10.1126/science.8066464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baumann P, Benson FE, West SC. Human Rad51 protein promotes ATP-dependent homologous pairing and strand transfer reactions in vitro. Cell. 1996;87:757–766. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81394-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weil MK, Chen AP. PARP inhibitor treatment in ovarian and breast cancer. Curr. Probl. Cancer. 2011;35:7–50. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Von Minckwitz G, et al. Neoadjuvant carboplatin in patients with triple-negative and HER2-positive early breast cancer (GeparSixto; GBG 66): a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:747–756. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sikov WM, et al. Impact of the addition of carboplatin and/or bevacizumab to neoadjuvant once-per-week paclitaxel followed by dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide on pathologic complete response rates in stage II to III triple-negative breast cancer: CALGB 40603 (Alliance) J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:13–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomas L, Stamberg J, Gojo I, Ning Y, Rapoport AP. Double minute chromosomes in monoblastic (M5) and myeloblastic (M2) acute myeloid leukemia: two case reports and a review of literature. Am. J. Hematol. 2004;77:55–61. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sanborn JZ, et al. Double minute chromosomes in glioblastoma multiforme are revealed by precise reconstruction of oncogenic amplicons. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6036–6045. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vogt N, et al. Molecular structure of double-minute chromosomes bearing amplified copies of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in gliomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11368–11373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402979101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Turner KM, et al. Extrachromosomal oncogene amplification drives tumour evolution and genetic heterogeneity. Nature. 2017;543:122–125. doi: 10.1038/nature21356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.deCarvalho AC, et al. Discordant inheritance of chromosomal and extrachromosomal DNA elements contributes to dynamic disease evolution in glioblastoma. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:708–717. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0105-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garsed DW, Holloway AJ, Thomas DM. Cancer-associated neochromosomes: a novel mechanism of oncogenesis. Bioessays. 2009;31:1191–1200. doi: 10.1002/bies.200800208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Garsed DW, et al. The architecture and evolution of cancer neochromosomes. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:653–667. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Venter JC, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Piégu B, Bire S, Arensburger P, Bigot Y. A survey of transposable element classification systems--a call for a fundamental update to meet the challenge of their diversity and complexity. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015;86:90–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hancks DC, Kazazian HH. Active human retrotransposons: variation and disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2012;22:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Clapp J, et al. Evolutionary conservation of a coding function for D4Z4, the tandem DNA repeat mutated in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:264–279. doi: 10.1086/519311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tubio JMC, et al. Mobile DNA in cancer. Extensive transduction of nonrepetitive DNA mediated by L1 retrotransposition in cancer genomes. Science. 2014;345:1251343. doi: 10.1126/science.1251343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miki Y, et al. Disruption of the APC gene by a retrotransposal insertion of L1 sequence in a colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1992;52:643–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rodriguez-Martin B., et al. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes reveals driver rearrangements promoted by LINE-1 retrotransposition in human tumours. BioRxiv 2017. 10.1101/179705.

- 89.Beck CR, Garcia-Perez JL, Badge RM, Moran JV. LINE-1 elements in structural variation and disease. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2011;12:187–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shukla R, et al. Endogenous retrotransposition activates oncogenic pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2013;153:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee E, et al. Landscape of somatic retrotransposition in human cancers. Science. 2012;337:967–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1222077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ewing AD, et al. Widespread somatic L1 retrotransposition occurs early during gastrointestinal cancer evolution. Genome Res. 2015;25:1536–1545. doi: 10.1101/gr.196238.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Solyom S, et al. Extensive somatic L1 retrotransposition in colorectal tumors. Genome Res. 2012;22:2328–2338. doi: 10.1101/gr.145235.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Helman E, et al. Somatic retrotransposition in human cancer revealed by whole-genome and exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2014;24:1053–1063. doi: 10.1101/gr.163659.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ju YS, et al. Frequent somatic transfer of mitochondrial DNA into the nuclear genome of human cancer cells. Genome Res. 2015;25:814–824. doi: 10.1101/gr.190470.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yuan Y., et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of mitochondrial genomes in human cancers. BioRxiv 2017. 10.1101/161356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.Riley DR, et al. Bacteria-human somatic cell lateral gene transfer is enriched in cancer samples. PLoS. Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1003107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Robinson KM, Sieber KB, Dunning Hotopp JC. A review of bacteria-animal lateral gene transfer may inform our understanding of diseases like cancer. PLoS. Genet. 2013;9:e1003877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tang KW, Alaei-Mahabadi B, Samuelsson T, Lindh M, Larsson E. The landscape of viral expression and host gene fusion and adaptation in human cancer. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2513. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lehoux M, D’Abramo CM, Archambault J. Molecular mechanisms of human papillomavirus-induced carcinogenesis. Public Health Genom. 2009;12:268–280. doi: 10.1159/000214918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Akagi K, et al. Genome-wide analysis of HPV integration in human cancers reveals recurrent, focal genomic instability. Genome Res. 2014;24:185–199. doi: 10.1101/gr.164806.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peter M, et al. Frequent genomic structural alterations at HPV insertion sites in cervical carcinoma. J. Pathol. 2010;221:320–330. doi: 10.1002/path.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. Mitochondrial evolution. Science. 1999;283:1476–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Adams KL, Palmer JD. Evolution of mitochondrial gene content: gene loss and transfer to the nucleus. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003;29:380–395. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Timmis JN, Ayliffe MA, Huang CY, Martin W. Endosymbiotic gene transfer: organelle genomes forge eukaryotic chromosomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:123–135. doi: 10.1038/nrg1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ju YS. Intracellular mitochondrial DNA transfers to the nucleus in human cancer cells. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2016;38:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Alexandrov LB, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Willis NA, et al. Mechanism of tandem duplication formation in BRCA1-mutant cells. Nature. 2017;551:590–595. doi: 10.1038/nature24477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Li Y., et al. Patterns of structural variation in human cancer. BioRxiv 2017. 10.1101/181339.

- 110.Roix JJ, McQueen PG, Munson PJ, Parada LA, Misteli T. Spatial proximity of translocation-prone gene loci in human lymphomas. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:287–291. doi: 10.1038/ng1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang Y, et al. Spatial organization of the mouse genome and its role in recurrent chromosomal translocations. Cell. 2012;148:908–921. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wala J. A., et al. Selective and mechanistic sources of recurrent rearrangements across the cancer genome. BioRxiv 2017. 10.1101/187609.

- 113.Li J, et al. Genomic hypomethylation in the human germline associates with selective structural mutability in the human genome. PLoS. Genet. 2012;8:e1002692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Drier Y, et al. Somatic rearrangements across cancer reveal classes of samples with distinct patterns of DNA breakage and rearrangement-induced hypermutability. Genome Res. 2013;23:228–235. doi: 10.1101/gr.141382.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Coquelle A, Pipiras E, Toledo F, Buttin G, Debatisse M. Expression of fragile sites triggers intrachromosomal mammalian gene amplification and sets boundaries to early amplicons. Cell. 1997;89:215–225. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Coquelle A, Rozier L, Dutrillaux B, Debatisse M. Induction of multiple double-strand breaks within an hsr by meganucleaseI-SceI expression or fragile site activation leads to formation of double minutes and other chromosomal rearrangements. Oncogene. 2002;21:7671–7679. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Canela A, et al. Genome organization drives chromosome fragility. Cell. 2017;170:507–521.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zheng J. Oncogenic chromosomal translocations and human cancer (Review). Oncol. Rep. 30, 2011–2019 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 119.Weischenfeldt J, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of somatic copy-number alterations implicates IRS4 and IGF2 in enhancer hijacking. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:65–74. doi: 10.1038/ng.3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Glodzik D, et al. A somatic-mutational process recurrently duplicates germline susceptibility loci and tissue-specific super-enhancers in breast cancers. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:341–348. doi: 10.1038/ng.3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.GTEx Consortium, Laboratory, Data Analysis &Coordinating Center (LDACC)—Analysis Working Group, Statistical Methods groups—Analysis Working Group, Enhancing GTEx (eGTEx) groups, NIH Common Fund, NIH/NCI. et al. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature550, 204–213 (2017)..

- 122.Chiang C, et al. The impact of structural variation on human gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:692–699. doi: 10.1038/ng.3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lupiáñez DG, et al. Disruptions of topological chromatin domains cause pathogenic rewiring of gene-enhancer interactions. Cell. 2015;161:1012–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Harewood L, et al. Hi-C as a tool for precise detection and characterisation of chromosomal rearrangements and copy number variation in human tumours. Genome Biol. 2017;18:125. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sanders AD, Falconer E, Hills M, Spierings DCJ, Lansdorp PM. Single-cell template strand sequencing by Strand-seq enables the characterization of individual homologs. Nat. Protoc. 2017;12:1151–1176. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Voet T, et al. Single-cell paired-end genome sequencing reveals structural variation per cell cycle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:6119–6138. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wang H, et al. A perspective on chromosomal double strand break markers in mammalian cells. Jacobs J. Radiat. Oncol. 2014;1:003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Canela A, et al. DNA breaks and end resection measured genome-wide by end sequencing. Mol. Cell. 2016;63:898–911. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Davis CA, et al. The Encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE): data portal update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D794–D801. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.FANTOM Consortium and the RIKEN PMI and CLST (DGT. Forrest ARR, et al. A promoter-level mammalian expression atlas. Nature. 2014;507:462–470. doi: 10.1038/nature13182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rushlow DE, et al. Characterisation of retinoblastomas without RB1 mutations: genomic, gene expression, and clinical studies. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:327–334. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Northcott PA, et al. Enhancer hijacking activates GFI1 family oncogenes in medulloblastoma. Nature. 2014;511:428–434. doi: 10.1038/nature13379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Drier Y, et al. An oncogenic MYB feedback loop drives alternate cell fates in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:265–272. doi: 10.1038/ng.3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Aplan PD, et al. Disruption of the human SCL locus by “illegitimate” V-(D)-J recombinase activity. Science. 1990;250:1426–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.2255914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Liau WS, et al. Aberrant activation of the GIMAP enhancer by oncogenic transcription factors in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2017;31:1798–1807. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]