Abstract

Rabies, caused by rabies virus (RABV), is still the deadliest infectious disease. Mechanism of host immune response upon RABV infection is not yet fully understood. Accumulating evidences suggest that long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) plays key roles in host antiviral responses. However, expression profile and function of lncRNAs in RABV infection remain unclear. In the present study, expression profile of lncRNAs and mRNAs profiles were investigated in RABV-infected brain tissues of mice by RNA sequencing. A total of 140 lncRNAs and 3,807 mRNAs were differentially expressed in RABV-infected animals. The functional annotation and enrichment analysis using Gene Oncology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) revealed that differentially expressed transcripts were predominantly involved in signaling pathways related to host immune response. The expression profiles of the selected lncRNAs in brains of mice during RABV infections were verified by quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). To our knowledge, this is the first report to profile the lncRNA expression in RABV infected mice. Our findings provide insights into understanding the role of lncRNAs in host immune response against RABV infection.

Introduction

Rabies is one of the deadliest zoonosis disease caused by rabies virus (RABV)1. It is nearly 100% fatal once clinical symptoms develop2. Rabies claims more than 60,000 human deaths annually, which is more than any other single zoonotic disease in the world. More than 80% of the deaths occurred in countries in Asia. China is the second most burden countries in the world. It showed that 40% of the deaths are children and 99% of the cases are resulted from bites of infected dogs3. Meanwhile, in developed countries like USA and Canada, bat RABV poses a serious threat to public health4.

RABV is a negative-stranded RNA virus that belongs to the family Rhabdoviridae, genus Lyssavirus, and species Rabies lyssavirus. Genome of RABV is approximately 12 kb and encodes five structural proteins, i.e. nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), glycoprotein (G) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L)5. Most RABV infections start from a dermal or muscular wound. RABV replicates locally in muscle tissue and then enters a neuron and spreads to motor neurons through synapses between muscles and motor neurons. It transports to central neural system (CNS) by retrograde axonal transport. Displaying of clinical symptoms means RABV reached the CNS6, where RABV elicit neuronal dysfunction and ultimately lead to death7.

Interferon (IFN)-mediated immune response is essential for protection against RABV infection8. Studies have shown that IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), which were the effector of type I IFN response, exerted diverse antiviral effects9,10. Previous studies have demonstrated that deficiency in IFN production increased susceptibility to RABV in mouse model11. Although much advances have been achieved in prevention of RABV, the mechanism by which RABV causes fatal disease remains unclear.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides and incapable of coding functional proteins. Most lncRNAs are capped at the 5′-end and polyadenylated at the 3′-end12. According to their genomic position, lncRNAs are generally classified as intergenic, intronic, bidirectional, antisense and pseudogene13. In the recent years, increasing evidences suggested that lncRNAs regulated numerous physiological processes, such as differentiation14, apoptosis15, development16, and immune responses17. In 2006, Rangarajan et al.18 first reported a virus-induced lncRNA (VINC) in the CNS of mouse after Japanese encephalitis infection. Since then, many viral infections such as influenza (IAV)19, HIV20, hepatitis B21 were reported to induce specific lncRNAs. LncRNA NRAV is downregulated during IAV infection and negatively regulates the transcription of ISGs22. Meanwhile, NRAV is the first lncRNA that is involved in inhibiting HIV-1 replication and facilitates the expression of antiviral genes during influenza virus and herpes simplex virus infection23. However, little is known about lncRNA expression profile and their regulating roles in immune responses during RABV infection.

To explore the role of lncRNAs during RABV infection, we analyzed the lncRNA expression profile in brain tissues of mice infected by RABV strain CVS-11 utilizing RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq). Our results indicated that RABV induced significant changes in lncRNA expression. Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis revealed that differentially expressed lncRNAs regulated immune response against RABV infection. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report profile the lncRNA expression in RABV infected mice. Our findings provide insights into understanding the role of lncRNAs in host immune response against RABV infection.

Results

RNA-seq and identification of differentially expressed lncRNA

To investigate lncRNA expression profile in mice infected with RABV, high-throughput RNA sequencing was performed on CVS11 infected brain tissues of mice. We sequenced 15 rRNA-deprived total RNA samples, including 5 brain tissues of mock-infected mice and 10 brain tissues of CVS-11 infected of mice. Each assay was duplicates. Average 80 million raw reads were produced for each sample using Illumina HiSeq platform by two-pair end sequencing. After removing the low-quality and adaptor sequences, clean reads were further analyzed.

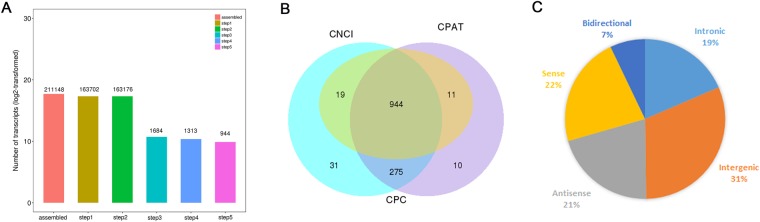

Based on the specific structure and non-coding characteristics of lncRNAs, transcripts were scanned by 5 steps to identify the annotated and novel lncRNAs. 944 novel lncRNAs were assembled by Cuffilinks (Fig. 1A). The coding capacity of transcripts were evaluated by three tools, i.e. Coding-Non-Coding-Index (CNCI), Coding Potential Calculator (CPC) and coding-potential assessment tool(CPAT) (Fig. 1B). Meanwhile, based on the relative genomic locations to coding genes, the lncRNAs identified were divided into five classifications including intergenic lncRNA (31%), intronic lncRNA (19%), antisense lncRNA (21%), sense lncRNA (22%) and bidirectional lncRNA (7%) (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Identification of novel lncRNAs in brain tissues of mice after RABV infection. (A) Screen of lncRNAs in RABV infected brain tissues of mice. (B) Evaluating the coding capacity of assembled transcripts using CNCI, CPC and CPAT. (C) Classification of lncRNAs based on genomic location.

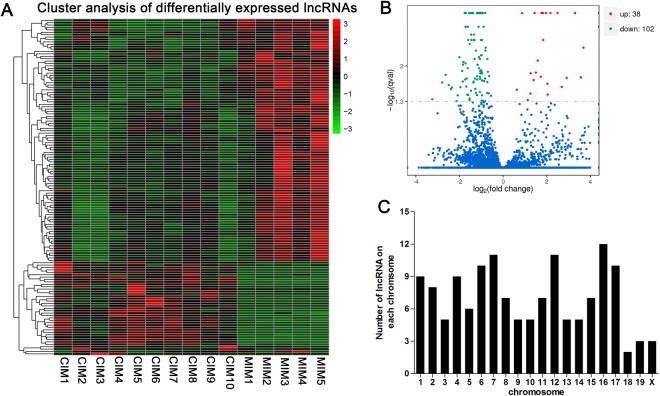

Hierarchical clustering was used to analyze the lncRNA expression profiles in mock- or RABV-infected mice. As it was observed, the lncRNA expression profiles were significantly modified after RABV infection (Fig. 2A). A total of 140 lncRNAs were differentially expressed in mice at days post infection (dpi) 8, with 38 lncRNAs up-regulated and 102 lncRNAs down-regulated (Fig. 2B). Of the dysregulated lncRNAs, 20 lncRNAs were changed with a fold change (FC) of more than 5.0, compared with mock infected group (Table 1). The most up-regulated lncRNA was AW112010, with a FC of more than 140, and the most down-regulated transcript was a novel lncRNA, termed LNC_000415 with a FC of more than 9 (Table 1).

Figure 2.

The expression profile of lncRNAs in brain tissues of mice. (A) Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed lncRNAs. (B) Volcano plot of differentially expressed lncRNAs in RABV infected brain tissues of mice compared with mock infected controls. (C) Distribution of differentially expressed lncRNAs in each chromosome.

Table 1.

The top 20 differentially expressed lncRNAs in RABV infected mice.

| lncRNA ID | Ensembl | Locus | Regulation | Fold change | q value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AW112010 | ENSMUST00000099676 | 19:11047616–11050566 | Up | 141.25 | 0.00091 |

| AU020206 | ENSMUST00000181224 | 7:75769761–75782099 | Up | 58.46 | 0.00091 |

| AI662270 | ENSMUST00000143673 | 11:83223575–83226604 | Up | 40.52 | 0.00091 |

| Ifi30 | ENSMUST00000222087 | 8:70762773–70766663 | Up | 32.01 | 0.00091 |

| Gm20559 | ENSMUST00000201831 | 6:3333193–3346071 | Up | 23.93 | 0.00091 |

| BC018473 | ENSMUST00000156293 | 11:116752166–116759373 | Up | 16.60 | 0.014012 |

| LNC_000406 | — | 17:29430267–29437310 | Up | 16.52 | 0.005568 |

| H19 | ENSMUST00000136359 | 7:142575528–142578143 | Up | 12.83 | 0.004372 |

| LNC_000104 | — | 11:63619195–63620383 | Up | 11.85 | 0.016781 |

| Gm12840 | ENSMUST00000156081 | 4:117700187–117700923 | Up | 9.82 | 0.00091 |

| LNC_000415 | — | 17:66233506–66266999 | Down | 9.52 | 0.045051 |

| 3930402G23Rik | ENSMUST00000040608 | 8:10924426–10928696 | Up | 7.51 | 0.017203 |

| 2810407A14Rik | ENSMUST00000189929 | 16:87787571–87839293 | Down | 6.94 | 0.021077 |

| F630028O10Rik | ENSMUST00000147681 | X:96239925–96243636 | Up | 6.44 | 0.025813 |

| LNC_000019 | — | 1:77522264–77560578 | Down | 6.23 | 0.014936 |

| LNC_000745 | — | 6:95905307–95922964 | Down | 5.65 | 0.023704 |

| Gm7932 | ENSMUST00000205047 | 6:48860328–48866083 | Up | 5.63 | 0.00091 |

| Gm31518 | ENSMUST00000211925 | 8:95593421–95613932 | Down | 5.27 | 0.028657 |

| LNC_000035 | — | 1:30120172–30122900 | Down | 5.10 | 0.026609 |

The differentially expressed lncRNA in RABV-infected mice were widely scattered in all chromosomes, while the numbers were various in different chromosomes. Chromosome 7, 12 and 16 had the largest number of altered lncRNAs, while 18,19 and x had the least altered lncRNAs (Fig. 1C).

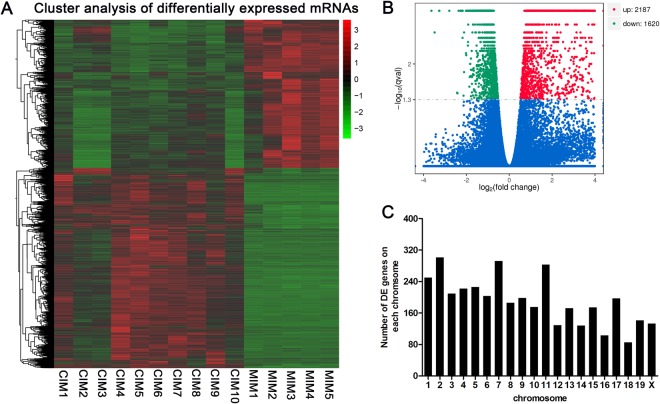

Differential expression of mRNAs in brain tissues of mice between mock- and RABV-infected groups

We also examined the change of mRNA expression in brain tissues of mice post CVS-11 infection. Hierarchical cluster analysis showed that mRNA expression profile was significantly changed in mice after RABV infection compared with mock-infected controls (Fig. 3A). A total of 3,807 lncRNAs were differentially expressed in the CVS-11 infected mice (FC ≥ 2 and P < 0.05), including 2,187 up-regulated and 1,620 down-regulated (Fig. 3B). To our surprise, 67 genes were upregulated with a fold change of more than 100 after infection. The most up-regulated gene was Cyba (FC = 4.75E + 30). The most down-regulated genes in our study are Alb, with a fold change of 31.16. The top 20 differentially expressed genes were listed in Table 2.

Figure 3.

The expression profile of mRNAs in brain tissues of mice (A) Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed mRNAs. (B) Volcano plot of differentially expressed mRNAs in RABV infected brain tissues of mice compared with mock infected controls. (C) Distribution of differentially expressed lncRNA in each chromosome.

Table 2.

The top 20 differentially expressed mRNAs in RABV infected mice.

| Gene symbol | Ensembl ID | Locus | Regulation | Fold change | q value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyba | ENSMUST00000212600 | 8:119910359–124345722 | Up | 4.74E + 30 | 0.027449 |

| Lif | ENSMUST00000066283 | 11:4257556–4272514 | Up | 33775.75 | 0.042156 |

| Ifit1bl2 | ENSMUST00000087357 | 19:34617048–34640743 | Up | 8902.53 | 0.036319 |

| Txk | ENSMUST00000113604 | 5:72695977–72752777 | Up | 4014.77 | 0.033761 |

| Oas3 | ENSMUST00000044833 | 5:120753097–120777661 | Up | 816.25 | 0.022834 |

| H2-Q6 | ENSMUST00000174699 | 17:35424849–35430055 | Up | 739.78 | 0.008388 |

| Irf7 | ENSMUST00000026571 | 7:141228788–141266481 | Up | 607.47 | 0.016781 |

| Fcgr4 | ENSMUST00000078825 | 1:171018919–171029761 | Up | 602.56 | 0.018905 |

| Ly6c2 | ENSMUST00000100542 | 15:75108160–75111970 | Up | 596.57 | 0.004372 |

| H2-Q7 | ENSMUST00000116598 | 17:35439154–35443773 | Up | 566.59 | 0.049174 |

| Ifi47 | ENSMUST00000046704 | 11:48904655–49135387 | Up | 544.35 | 0.036963 |

| Gbp10 | ENSMUST00000065588 | 5:105214906–105293696 | Up | 512.67 | 0.042532 |

| Nlrc5 | ENSMUST00000211816 | 8:94422897–94527272 | Up | 486.41 | 0.029481 |

| Iigp1 | ENSMUST00000066912 | 18:60376028–60392627 | Up | 454.09 | 0.00091 |

| F830016B08Rik | ENSMUST00000171297 | 18:60293379–60303016 | Up | 366.58 | 0.00091 |

| Lcn2 | ENSMUST00000050785 | 2:32384632–32388252 | Up | 351.27 | 0.00091 |

| Serpina3g | ENSMUST00000043315 | 12:104236251–104241939 | Up | 347.72 | 0.037618 |

| Ifi204 | ENSMUST00000111214 | 1:173747292–173766919 | Up | 347.23 | 0.00091 |

| Igtp | ENSMUST00000035266 | 11:58199555–58222782 | Up | 336.08 | 0.00091 |

| Ifi209 | ENSMUST00000056071 | 1:173630916–173647928 | Up | 335.73 | 0.003719 |

Similar to the distribution pattern of lncRNAs, the differentially expressed mRNAs in RABV infected mice were not equally scattered among chromosomes. The chromosome 2, 7 and 11 had the most differentially expressed mRNAs and chromosome 16 and 18 have the least numbers, while Y chromosome was absent of differentially expressed mRNAs (Fig. 3C).

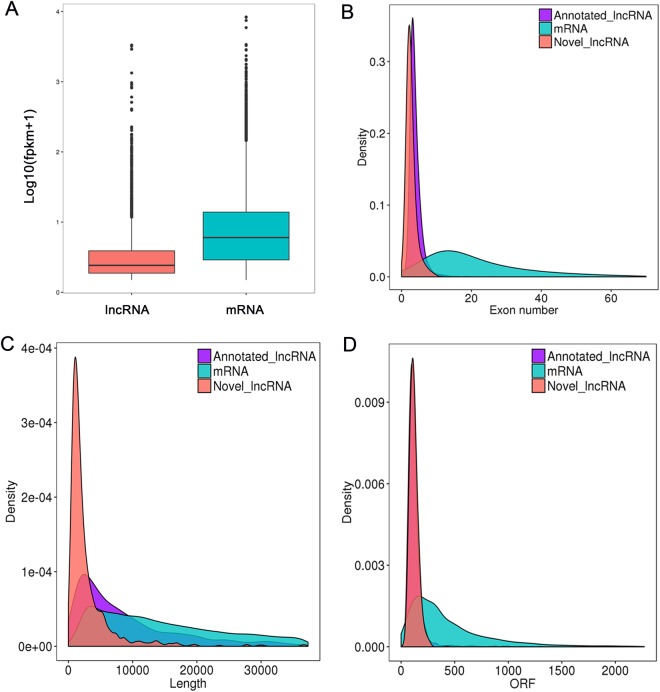

Genomic features of lncRNAs and mRNAs in mice

Then we systematically analyzed the basic features of the lncRNAs and compared them with protein-coding genes. As shown in Fig. 4A, the average expression levels of lncRNAs were lower than those of mRNAs. The length of transcripts of lncRNAs was shorter than those of mRNAs (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the exon number of lncRNA was also less than those of mRNAs (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, most of the mRNAs had a longer Open Reading Frames (ORFs) than those of lncRNAs (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Genomic features of lncRNAs and mRNAs in RABV infected brain tissues of mice. (A) Comparison of lncRNAs and mRNAs expression level. (B) Comparison of exon number between lncRNA and mRNAs (C) Length distribution of lncRNAs and mRNAs. (D) Length of ORFs between lncRNAs and mRNAs.

Functional prediction of RABV-induced lncRNAs

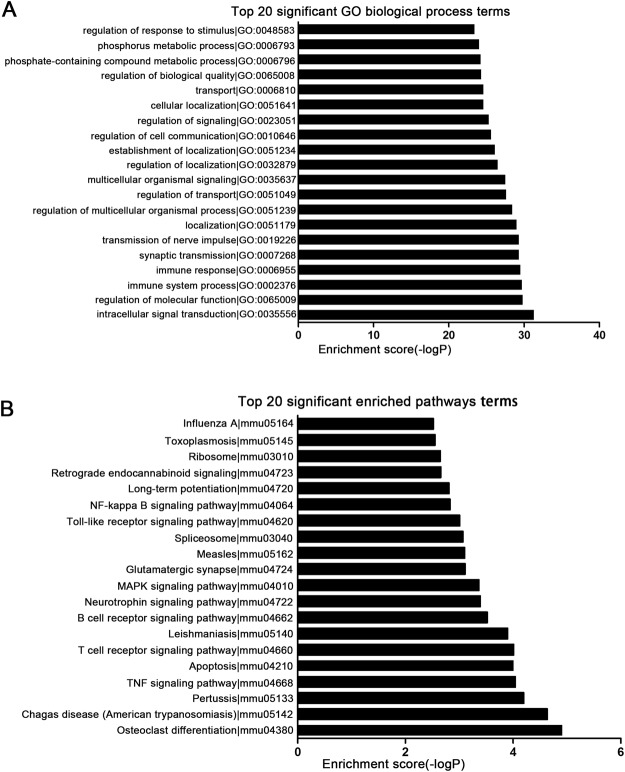

To better understand the functions of differentially expressed lncRNAs in RABV infected mice, GO term and KEGG pathway analysis was performed to predict the functions of cis- and trans- target genes of differentially expressed lncRNAs. We found that the target genes of differentially expressed lncRNAs were highly enriched in biological processes like Intracellular signal transduction, Immune response and Synaptic transmission. The top 20 significant GO biological terms were presented in Fig. 5A. The targets of differentially expressed lncRNAs were involved in important signaling pathways, such as TNF signaling pathway, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, NF-κB signaling pathway and MAPK signaling pathway. The top 20 significant enriched pathways were presented in Fig. 5B. These findings suggested that lncRNAs regulate the immune responses during RABV infection.

Figure 5.

Go enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis of target genes of differentially expressed lncRNAs. (A) Top 20 GO biological processes enriched among target genes of differentially expressed lncRNAs. (B) The top 20 pathways enriched among target genes of differentially expressed lncRNAs.

Validation of differentially expressed lncRNAs by quantitative PCR

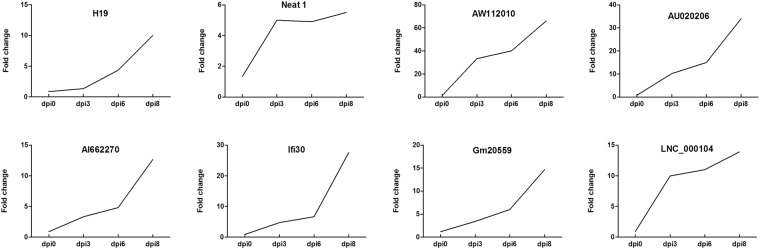

RNA-seq analysis indicated that 140 lncRNA were differentially expressed post RABV infection. To validate the RNA-seq data, we investigated the expression levels of the eight most up-regulated lncRNAs at four time points after RABV infection, i.e. dpi 0, 3, 6 and 8, using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The results showed that expression patterns of these eight selected lncRNAs were consistent with RNA-seq data (Fig. 6). Moreover, the levels of these lncRNAs continuously increased from dpi 3 to dpi 8, which may reflect their correlations with progression of clinical symptom.

Figure 6.

Expression patterns of selected differentially expressed lncRNAs on different time points post RABV infection. Mice were infected with CVS-11 or equal volume of DMEM, and brain samples were collected at dpi 0, 3, 6 and 8 for analysis of selected lncRNAs by qRT-PCR.

Discussion

RABV is still one of the deadliest zoonoses and remains as an important threat to public health in the world. Currently, although rabies is prevented by giving post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) promptly, it lacks curable treatment. Effective protection of exposed subjects of rabies correlates with the induction of rabies-specific virus-neutralizing antibodies (VNAs). However, current vaccine not only requires multiple injections but also time-consuming and expensive, thus prevent many rabies exposed subjects away from timely vaccinated. As a result, rabies still cause around 70,000 deaths annually around the world despite efficacious vaccines are available24. Therefore, it is an emergent need to develop a cost-effective vaccine which elicits long-lasting immunity by a single vaccination and could ideally clear virus infection from the CNS.

During infection, virus is detected by pattern-recognition receptors (PPRs), either canonical or non-canonical, which activate nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and interferon regulatory transcription factors (IRFs) and induce the expression of type I interferons25,26. When RABV infections occur, the innate immune responses are promptly induced. PRRs are activated in the periphery and RABV is recognized in the CNS by retinoic-acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), which sequentially activate NF-κB and type I IFN-regulated responses27,28. However, although much advance has been achieved on RABV biology and anti-RABV immune response, the mechanism underlies how RABV causes fatal disease is not fully understood. Previously, we found that protein-coding gene profile of host cell was significantly changed after RABV infection. We have identified some genes that function against viral replication, i.e. interferon-stimulated genes 15 (ISG15) and ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme 7(UBA7)29,30. Recently, many studies have suggested that lncRNAs played key roles in the host immune response against viral infections31,32. However, the role of lncRNAs in RABV infection remained unclear. In the present study, we examined the expression profile of lncRNAs and mRNAs in brain tissues of mice after RABV infection. We identified 140 lncRNAs that were significantly differentially expressed between mock- or RABV-infected mice. To be noted, several lncRNAs, i.e. AW112010, AU020206, AI662270 and Ifi30 were up-regulated with a fold change of more than 30. The expression of lncRNAs has been confirmed by qRT-PCR. The dynamic change of lncRNA expression in brain tissues of mice further suggested that lncRNAs might play significant biological roles in RABV infection. Meanwhile, our results showed that 3,807 mRNAs were differentially expressed after infected with CVS-11, including 2,187 up-regulated and 1,620 down-regulated. We also characterized the genomic feature of lncRNAs in brain tissues of mice. Compared with mRNAs, lncRNAs are less enriched in expression, shorter in length, have fewer exons33–35. Previous studies have demonstrated that lncRNAs have poor primary sequence conservation compared to protein-coding genes36. It has been reported that less than 6% of zebrafish lncRNAs exhibited sequence conservation with lncRNAs of human or mouse and the sequence conservation of lncRNAs between human and other species were only about 12%37,38. We also evaluated the sequence conservation of the differentially expressed lncRNAs identified from RABV-infected mouse and found that only about 15% of the lncRNAs appeared to be conserved in human.

Unlike protein-coding genes or microRNAs, the sequences or structures of lncRNAs were currently uninformative for predicting its function39. In the present study, the function of lncRNAs was predicted according to their cis- or trans- target genes. GO terms were significantly enriched in biological processes like Intracellular signal transduction, Regulation of molecular function, Immune system process, Synaptic transmission. It suggested that lncRNAs induced by RABV infection may regulate the immune responses against RABV. KEGG pathway analysis showed that target genes of differentially expressed lncRNA were enriched in the pathways like NF-κB signaling pathway, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, T cell receptor signaling pathway and TNF signaling pathway, which suggested that lncRNAs take part in host immune response against virus infection through various pathways.

In conclusion, the present study is for the first time to report the expression profile of lncRNAs upon RABV infection in mice. The results suggested that lncRNAs might have key roles in regulating immune responses post RABV infection and exert important biological effects.

Methods

Virus

The RABV strain challenge virus standard (CVS-11) was kindly provided by Military Veterinary Institute, Academy of Military Medical Sciences (Changchun, China). Mouse neuroblastoma (NA) cells was seeded in 6-well-plate with a concentration of 4 * 105 in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100U of penicillin/ml, and 100 mg of streptomycin/ml at 37 °C. CVS-11 was added with a MOI of 0.1. The virus was amplified for 72 h and the supernatant were sowed. The virus titer was determined by plaque formation assay on baby hamster Syrian kidney (BHK-21) cells.

RABV infection

Six-to-eight-week-old male BALB/c mice were purchased from the Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center. Mice were kept in an animal room with stable temperature and light, freely fed and drink. Mice were randomly assigned to two groups: ten for CVS-11 infected group and another ten for mock infected group. For virus infected group, mice were inoculated intracranially with 200 plaque-forming units (PFU) of CVS-11 in 50 µl DMEM, whereas the mock infected group was injected with equal volume of DMEM. On day 8 post infection, mice infected with CVS-11 showed clinical signs, i.e. disordered movement, hunched back, trembling and shaking. Mice from both groups were euthanized, and brain samples were collected. All animal experiments were performed following the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the experimental protocols were approved by the Ethical Committee of Meizhou People’s Hospital (Huangtang Hospital), Meizhou Hospital Affiliated to Sun Yat-sen University, Guangdong, China. All virus experiments were performed at Biosafety Level 2 laboratory.

Total RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted from brain tissues of mice using RNeasy Kit (TianGene, Beijing, China) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The quantity and purity of total RNA were evaluated by Nanodrop 2000. The ratio of A260/A280 should be from 1.8 to 2.0. RNA integrity was analyzed by the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA).

High throughput sequencing

Ribo-Zero rRNA removal kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI, USA) was used to remove ribosomal RNA. RNA libraries were prepared using the rRNA-depleted RNA with NEBNext® Ultra™ Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA). Library sequencing was performed on a Illumina HiSeq2000 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) in ShenZhen Realomics Inc.

Bioinformatic analysis

Raw data were filtered by removing the adaptors, low-quality reads and poly-N reads to obtain clean data using the SOAPnuke. The Q20, Q30, and GC information were calculated to evaluate the clean data. Then the filtered reads were mapped to the mice reference genome (version: mus_musculus. GRCm38) by Tophat 2. The transcripts were assembled with the mapped reads by reference annotation based transcripts (BRAT) method using Cufflink40.

The assembled transcript was identified as a novel lncRNA if (1) exon number ≥ 2, (2) length > 200 nt, (3) FPKM ≥ 0.5, (4) without coding capacity, (5) don’t overlap with mRNA or annotated lncRNA. Coding ability was predicted using coding-non-coding-index (CNCI), coding potential calculator (CPC) and coding-potential assessment tool (CPAT). The expression analysis was performed using Cuffdiff.

Expressed profile of lncRNAs and mRNAs in brains of mice upon RABV infection were shown in Tables S1 and S2.

GO and KEGG pathway analyses

To predict the target genes of differentially expressed lncRNAs, cis- and trans- analyses were performed. The genes located within a 10 kb window upstream or downstream of lncRNAs were classified as the cis target genes. The trans target genes were predicted on the expression levels of coding genes.

GO enrichment analyses were performed to identify biological processes associated with cis- or trans- target genes of lncRNA. KEGG was used to analyze the associated pathways of cis- or trans- target genes of the lncRNAs. A false discovery rate (FDR) was used to correct the P values. A corrected P value (Q values) <0.05 were considered significant.

Real-time RT-PCR assay

Real-time RT-PCR was performed to detect express of the selected lncRNAs using Luna® Universal One-Step RT-qPCR Kit (New England Biolabs, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Primers used for validation of lncRNA expression were shown in Table 3. The amplify program is as follow: 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles (95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s). The specificity of the amplified products was evaluated using dissociation curves. Relative expression of lncRNA were normalized to Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The tests were triplicated.

Table 3.

Primers used for validation of expression of lncRNAs by qRT-PCR.

| LncRNAs | Primer sequences (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| H19 | Forward: GGGTCACAAGACACAGATGGGT |

| Reverse: CCAGTTATTGAGGCTCTGGCA | |

| Neat 1 | Forward: GCAGGACTAGGTGCGTAGTGGA |

| Reverse: GCTATCACCCTGGGCCAGA | |

| AW112010 | Forward: AAGTCTTCTGCCATCAAGCCA |

| Reverse: CCACTTGAGGTTTCCAGTGTGT | |

| AU020206 | Forward: CCTGCAGGCTTGATTTCAGTT |

| Reverse: AGGGCGTCTGTCAGCCAAGT | |

| AI662270 | Forward: GTGCACCCTAAGGATTTATAGGAA |

| Reverse: GCCAAAGTGTAAGCAACCAAGA | |

| Ifi30 | Forward: TACCATTTTTGTCCCTTCTGCTTC |

| Reverse: ACAGGGACTCATAATACAGGCTGAC | |

| Gm20559 | Forward: AGGATCATACAAATGAGTTGTGTGG |

| Reverse: CTGTATCTGTAGCTTCGTCTGCAAC | |

| LNC_000104 | Forward: TGTCATGTTGATCACTTGACTTCAG |

| Reverse: AGTCAAAGACAGATGGATGAGCAG | |

| GAPDH | Forward: TTCAACGGCACAGTCAAGGCA |

| Reverse: CCACCACATACTCAGCACCAGC |

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Student’s t-test or one-way Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (compare all groups to the control group). All data are demonstrated as the means ± S.D. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). For correlation studies, a two-tailed non-parametric Spearman analysis was used. P ≤ 0.05 were considered as significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank other colleagues whom were not listed in the authorship of Clinical Core Laboratory and Center for Precision Medicine, Meizhou People’s Hospital (Huangtang Hospital), Meizhou Hospital Affiliated to Sun Yat-sen University for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by The National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No.: 2016YFD0500405 to Dr. Pingsen Zhao), The National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No.: 2017YFD0501705 to Dr. Pingsen Zhao), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Grant No.: 2016A030307031 to Dr. Pingsen Zhao), Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Grant No.: A2016306 to Dr. Pingsen Zhao), and Key Scientific and Technological Project of Meizhou People’s Hospital (Huangtang Hospital), Meizhou Hospital Affiliated to Sun Yat-sen University, Guangdong Province, China (Grant No.: MPHKSTP-20170102 to Dr. Pingsen Zhao).

Author Contributions

P.Z. conceived and designed the study. S.L., Z.Z., T.J., P.Z. and X.X. wrote the first draft. S.L. and P.Z. planned and performed statistical analyses. S.L., T.J., M.X. and R.W. performed experiments. Z.Z., S.Y. and P.Z. contributed to the collection of data, discussions, and interpretation of the data. The decision to submit this manuscript for publication was made by all the authors and study principal investigators.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Pingsen Zhao, Sudong Liu, Zhixiong Zhong and Tianqi Jiang contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-30359-z.

References

- 1.Davis BM, Rall GF, Schnell MJ. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Rabies Virus (But Were Afraid to Ask) Annu Rev Virol. 2015;2:451–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-055157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rupprecht CE, Hanlon CA, Hemachudha T. Rabies re-examined. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:327–43. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fooks AR, et al. Current status of rabies and prospects for elimination. Lancet. 2014;384:1389–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62707-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dato VM, Campagnolo ER, Long J, Rupprecht CE. A Systematic Review of Human Bat Rabies Virus Variant Cases: Evaluating Unprotected Physical Contact with Claws and Teeth in Support of Accurate Risk Assessments. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wunner WH, Larson JK, Dietzschold B, Smith CL. The molecular biology of rabies viruses. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(Suppl 4):S771–84. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.Supplement_4.S771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly RM, Strick PL. Rabies as a transneuronal tracer of circuits in the central nervous system. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;103:63–71. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(00)00296-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lafon M. Evasive strategies in rabies virus infection. Adv Virus Res. 2011;79:33–53. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387040-7.00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivashkiv LB, Donlin LT. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:36–49. doi: 10.1038/nri3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoggins JW, et al. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature. 2011;472:481–5. doi: 10.1038/nature09907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoggins JW, et al. Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature. 2014;505:691–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chopy D, Detje CN, Lafage M, Kalinke U, Lafon M. The type I interferon response bridles rabies virus infection and reduces pathogenicity. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:353–67. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guttman M, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458:223–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Cao X. Long noncoding RNAs in innate immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:138–47. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang P, et al. The STAT3-binding long noncoding RNA lnc-DC controls human dendritic cell differentiation. Science. 2014;344:310–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1251456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huarte M, et al. A large intergenic noncoding RNA induced by p53 mediates global gene repression in the p53 response. Cell. 2010;142:409–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sauvageau M, et al. Multiple knockout mouse models reveal lincRNAs are required for life and brain development. Elife. 2013;2:e01749. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heward JA, Lindsay MA. Long non-coding RNAs in the regulation of the immune response. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:408–19. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saha S, Murthy S, Rangarajan PN. Identification and characterization of a virus-inducible non-coding RNA in mouse brain. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1991–5. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81768-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winterling C, et al. Evidence for a crucial role of a host non-coding RNA in influenza A virus replication. RNA Biol. 2014;11:66–75. doi: 10.4161/rna.27504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q, Chen CY, Yedavalli VS, Jeang KT. NEAT1 long noncoding RNA and paraspeckle bodies modulate HIV-1 posttranscriptional expression. MBio. 2013;4:e00596–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00596-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du Y, et al. Elevation of highly up-regulated in liver cancer (HULC) by hepatitis B virus X protein promotes hepatoma cell proliferation via down-regulating p18. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:26302–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.342113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rice AP. Roles of microRNAs and long-noncoding RNAs in human immunodeficiency virus replication. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2015;6:661–70. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouyang J, et al. NRAV, a long noncoding RNA, modulates antiviral responses through suppression of interferon-stimulated gene transcription. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:616–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dreesen DW. A global review of rabies vaccines for human use. Vaccine. 1997;15:Suppl, S2–6. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(96)00314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider WM, Chevillotte MD, Rice CM. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:513–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rieder M, Conzelmann KK. Interferon in rabies virus infection. Adv Virus Res. 2011;79:91–114. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387040-7.00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faul EJ, et al. Rabies virus infection induces type I interferon production in an IPS-1 dependent manner while dendritic cell activation relies on IFNAR signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001016. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Faber M, Dietzschold B, Hooper DC. The role of toll-like receptors in the induction of immune responses during rabies virus infection. Adv Virus Res. 2011;79:115–26. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387040-7.00007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao P, et al. Global gene expression changes in BV2 microglial cell line during rabies virus infection. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;20:257–69. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao P, et al. Inhibition of rabies virus replication by interferon-stimulated gene 15 and its activating enzyme UBA7. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;56:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carnero E, et al. Type I Interferon Regulates the Expression of Long Non-Coding RNAs. Front Immunol. 2014;5:548. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barriocanal M, Carnero E, Segura V, Fortes P. Long Non-Coding RNA BST2/BISPR is Induced by IFN and Regulates the Expression of the Antiviral Factor Tetherin. Front Immunol. 2014;5:655. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li T, et al. Identification of long non-protein coding RNAs in chicken skeletal muscle using next generation sequencing. Genomics. 2012;99:292–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren H, et al. Genome-wide analysis of long non-coding RNAs at early stage of skin pigmentation in goats (Capra hircus) BMC Genomics. 2016;17:67. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2365-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weikard R, Hadlich F, Kuehn C. Identification of novel transcripts and noncoding RNAs in bovine skin by deep next generation sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:789. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pang KC, Frith MC, Mattick JS. Rapid evolution of noncoding RNAs: lack of conservation does not mean lack of function. Trends Genet. 2006;22:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ulitsky I, Shkumatava A, Jan CH, Sive H, Bartel DP. Conserved function of lincRNAs in vertebrate embryonic development despite rapid sequence evolution. Cell. 2011;147:1537–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He Y, et al. The conservation and signatures of lincRNAs in Marek’s disease of chicken. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15184. doi: 10.1038/srep15184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:155–9. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.