Abstract

Purpose: To present an overview of fertility-related perceptions and describe the perceived negative/positive impact of (potential) infertility on romantic relationships among childhood cancer survivors.

Methods: Male and female long-term childhood cancer survivors (N = 92) aged 22–43 and 7–37 years postdiagnosis, completed an online survey about fertility-related perceptions (i.e., knowledge, beliefs, uncertainty, concern, and attitudes toward testing) and romantic relationships. Potential differences based on sociodemographic/cancer-specific factors were tested.

Results: Most survivors (82.4%, n = 75) knew about infertility risk due to childhood cancer treatment. Seventy percent (n = 65) reported being told they were personally at risk, but less than one-third believed it (29.2%, n = 19/65). Half of survivors (48.9%, n = 45) never underwent fertility testing and were unaware of their fertility status. Fertility-related uncertainty and concerns were more common among survivors without children and those who desired (additional) children (d's > 0.5). Among survivors without biological children (n = 52), partnered survivors felt more uncertain about their fertility than singles (d = 0.8). Ten survivors (10.9%) reported a negative impact of infertility on romantic relationships, 6 (6.5%) reported a positive impact, and 7 (7.6%) reported both (e.g., pressure on relationship, fights, break-ups, being closer, and open partner communication).

Conclusions: Fertility-related perceptions varied among survivors, but the majority never underwent fertility testing. Uncertainty or concerns differed by current circumstances (e.g., wanting children and relationship status). Providers should routinely discuss potential infertility and offer testing throughout survivorship. A negative impact on romantic relationships may seem small, but should be considered for survivors who desire children and may discover they are infertile in the future.

Keywords: : oncofertility, adult childhood cancer survivors, romantic relationships, fertility testing, survivorship care

Introduction

Due to improved treatment, a growing number of children diagnosed with cancer are now long-term survivors and reach reproductive age. However, survival often comes at the cost of various late effects. Endocrine impairments, which include infertility or premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), are among the most common late effects among childhood cancer survivors.1,2 Approximately 42%–66% of male and 11%–26% of female childhood cancer survivors face infertility later in life, but rates largely depend on the type of treatment (with even higher rates after stem cell transplant).3 However, few psychological studies have focused on fertility-related perceptions and testing among adult survivors of childhood cancer, and even fewer have reported the potential impact of fertility problems on romantic relationships.

Although counseling at diagnosis about the effects of cancer treatment on fertility has improved, about 50% of long-term survivors do not recall such conversations,4 and many providers still hesitate to address fertility at diagnosis.5 In addition, survivorship care guidelines are unspecific about whether and how to routinely screen survivors for infertility,6,7 and it remains questionable if, how, and with whom fertility is addressed.8 Many adult survivors do not know their fertility status,9–11 despite the fact that most desire children of their own.12–15 These survivors may face unexpected challenges if they discover that they are infertile.9,16

Interestingly, survivors' beliefs about their fertility may not necessarily align with what they have been told, as some remain hopeful despite being told they are infertile, while others remain anxious even if reassured of their fertility.10,17,18 Yet, survivors' attitudes toward fertility testing are largely unknown. In one study focusing on infertility, some survivors mentioned barriers to fertility testing: fear of results, lacking knowledge about test procedures, and embarrassment.12

Importantly, fertility testing may not always provide clear results. Male fertility can be assessed with relative certainty through semen analyses. However, some survivors may be uncomfortable providing a sample, which is typically collected by masturbation. In contrast, fertility testing provides more ambiguous results for women. Transvaginal ultrasounds (examining antral follicle count) together with blood work (assessing hormone levels) may only yield tentative information, and again, some survivors may be uncomfortable with such procedures.

If survivors suspect being infertile, yet do not proceed with testing, it could create uncertainty, a state which could be stressful in itself. Thus, potential or confirmed infertility can cause various negative emotions, including worries, concerns, or distress.10,12,18–20 It may also be an obstacle to establishing9,21,22 or maintaining17,23 romantic relationships. Research among infertile, but otherwise healthy, couples showed that infertility can be emotionally and financially straining for both partners, but it may be experienced as more devastating among women.24,25

In sum, research has indicated limited fertility-related knowledge among childhood cancer survivors and negative emotional effects of infertility. However, studies are scarce and many research gaps remain. Therefore, this study systematically examined survivors' fertility-related knowledge and beliefs, attitudes toward fertility testing, fertility-related uncertainty and concerns, as well as the perceived impact of infertility on romantic relationships. Associations with background (e.g., sex and age) and cancer-specific factors (e.g., age at/type of diagnosis) were also examined.

Methods

Procedure and participants

This study represents a follow-up assessment of adult survivors of childhood cancer who previously participated in a study about psychosexual development.26 For the initial study, survivors were aged 20–40 years, diagnosed at age 5–18, and ≥5 years postdiagnosis. Data were initially collected online from 2013 to 2015, and in 2016, all 149 survivors who completed the initial project were reinvited to participate in this study. However, 28 survivors were lost to follow-up and 2 had died. Thus, approximately 119 survivors received our mailed invitation letter, and 92 (77.3%) completed the survey online. Participating survivors were 22–44 years old (M = 29.8, SD = 5.1), 63.0% female (n = 58), and had been diagnosed with leukemia (28.3%, n = 26), brain tumors (27.2%, n = 25), lymphoma (23.9%, n = 22), or other solid tumors (20.6%, n = 19). Survivors were 17.9 years postdiagnosis (range: 7–37 years), and about half (54.3%, n = 50) had been diagnosed before the age of 13. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, Ohio.

Measures

Fertility-related knowledge and beliefs

Knowledge and beliefs were assessed with four items inquiring the following: (1) whether survivors knew of infertility risk secondary to childhood cancer treatment (yes, unsure, or no), (2) the source of this information (e.g., provider, parent, or internet), (3) whether they recalled being told they were personally at risk for infertility and by whom (provider/parent), and (4) whether they believed it (yes, unsure, or not at all).

Fertility testing

One item assessed whether survivors had received formal fertility testing and whether they were aware of their fertility status, with the following answering options: Yes, I have been tested and I was told I should be fertile; Yes, I have been tested and I was told that my fertility is impaired; Yes, I have been tested and I was told that I am infertile; I know I'm fertile because I (or my partner) was pregnant; and I have not been tested and I don't know if I'm fertile. Those survivors endorsing the latter were (1) provided with a list of potential reasons for not having been tested (including an open-ended option) and asked (2) whether they would pursue fertility testing if it were offered (never, maybe, or yes). Descriptions about what fertility testing would entail were provided (i.e., semen analysis for men and transvaginal ultrasound and blood work for women).

Fertility-related uncertainty and concerns

Uncertainty was measured with one item asking participants to rate how uncertain they feel about potentially being infertile on a Likert-type scale (not at all–to a great extent, 0–3). To measure fertility-related concerns, we used the 3-item fertility potential subscale of the RCAC: Reproductive Concerns after Cancer Scale.27 These three items assess anxiety, concern, and worry surrounding potential infertility on a Likert-type scale (strongly disagree–strongly agree, 1–5). One item was slightly modified to suit male/female and partnered/single survivors (i.e., I am worried about my ability to get [my (potential) partner] pregnant). Higher scores indicate greater concerns and internal consistency was excellent in this study (Cronbach's α = 0.90).

Perceived impact on dating/romantic relationships

Survivors were asked whether they ever perceived a negative and/or positive impact on their romantic relationships due to (potential) infertility or worries about it (yes/no). If endorsed, they were asked to describe the nature of this impact in an open-ended text box.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all outcomes. Group comparisons on whether fertility-related knowledge, beliefs, and testing differed by sex, age, and age at or type of diagnosis were examined (χ2- and t-tests). Levels of fertility-related uncertainty and concerns were additionally tested for the potential influence of having children, wanting children, and relationship status (t-tests and ANOVAs). Cohen's d effect sizes were calculated to assess the magnitude of differences for continuous variables (Table 1). Power was sufficient (>0.7) to detect medium differences (e.g., d > 0.5) between two groups. However, comparing four groups (i.e., diagnosis type) had sufficient power only for large differences. All group comparisons were also explored among survivors without children (n = 52), but power was limited. Finally, a narrative summary of open-ended questions about a negative/positive impact of infertility on romantic relationships is presented.

Table 1.

Subgroup Differences in Fertility-Related Uncertainty and Concerns

| n | Uncertainty | Comparison | da | Concerns | Comparison | da | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole sample | 92 | 1.07 (1.09), 0–3 | 2.56 (1.38), 1–5 | ||||

| Survivors | |||||||

| With children | 40 | 0.64 (1.06) | t(89) = 3.39 | 0.72 | 2.06 (1.33) | t(78) = 2.84 | 0.65 |

| Without children | 52 | 1.38 (1.01) | p = 0.001 | 2.91 (1.32) | p = 0.006 | ||

| Survivors who wanted | |||||||

| (additional) children | 59 | 1.25 (1.11) | t(89) = −2.28 | 0.50 | 3.00 (1.34)b | t(78) = −5.12 | 1.26 |

| No (additional) children | 33 | 0.72 (0.99) | p = 0.025 | 1.48 (0.76) | p < 0.001 | ||

| Survivors who believed to be at riskc | |||||||

| Not at all | 29 | 0.14 (0.44)d | F(2, 88) = 33.08 | 0.79–2.40 | 1.74 (1.33)e | F(2, 77) = 8.87 | 0.72/1.25 |

| Maybe | 41 | 1.22 (0.88)d | p < 0.001 | 2.66 (1.23)e | p < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 21 | 2.05 (1.12)d | 3.37 (1.26)b,e | ||||

| Survivors without children, who were | |||||||

| Partnered | 30 | 1.70 (0.95) | t(50) = −2.79 | 0.79 | — | ||

| Single | 22 | 0.95 (0.95) | p = 0.007 | ||||

| Survivors without children, who wanted | |||||||

| Children | 40 | — | 3.23 (1.19)b | t(45) = −4.25 | 1.65 | ||

| No children | 12 | 1.38 (6.28) | p < 0.001 | ||||

Sex, age, age at diagnosis, or type of diagnosis were not associated with uncertainty or concerns; aCohen's d effect sizes are interpreted as small (>0.2), medium (>0.5), or large differences (>0.8)31; bsimilar to RCAC sample24 at p > 0.05; cn = 1 missing; dall subgroups significantly differed from another; ethe “not at all” subgroup significantly differed from the “maybe” and “yes” subgroup.

Results

Fertility-related knowledge and beliefs

Most survivors (82.4%, n = 75) reported knowing about risk of infertility secondary to childhood cancer treatment. This knowledge differed between diagnostic groups [χ2(6) = 31.21, p < 0.001], such that all lymphoma and solid tumor survivors, and 88.0% of leukemia survivors, but only 48.0% of brain tumor survivors, indicated knowing about this risk. Sources for learning about it were: medical team before/during (47.8%) or after treatment (37.0%), internet (29.3%), survivorship clinic (21.7%), parents after treatment (18.5%), and/or parents before/during treatment (16.3%).

Most survivors (70.7%, n = 65) reported that they had been told by their medical team (59.8%, n = 55) and/or parents (19.6%, n = 18) that they could be personally at risk for infertility. However, only 29.2% (n = 19/65) believed it, while 40.0% (n = 26/65) were unsure and 30.8% (n = 20/65) believed they were not at risk. Beliefs differed by age [F(2, 62) = 5.00, p = 0.010], with post hoc pairwise comparisons indicating that survivors who reported being unsure were younger than survivors who reported they believed they were not at risk (M = 28.0 vs. 32.6; p = 0.009). However, this seemed related to having children, as older survivors who believed to be not at risk had children more often [χ2(2) = 27.40, p < 0.001].

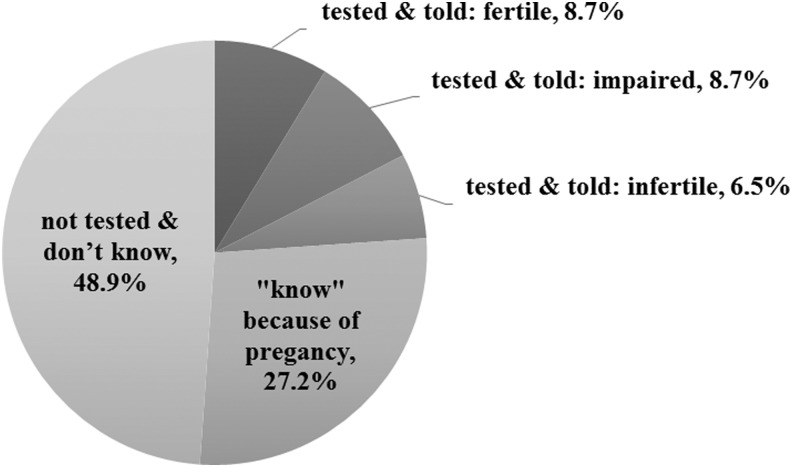

Fertility testing

Less than a quarter of survivors (23.9%, n = 22) had undergone fertility testing, and 27.2% (n = 25) assumed they were fertile because they had conceived/sired a pregnancy (Fig. 1). Yet, almost half (48.9%, n = 45) had never been tested and were unaware of their status. Reasons for not having been tested are presented in Table 2. Importantly, no survivor endorsed feeling uncomfortable with test procedures, embarrassment, or spiritual beliefs as barriers to testing. The 45 untested survivors were more often brain or solid tumor survivors [χ2(3) = 10.37, p = 0.016], diagnosed during childhood [χ2(1) = 5.39, p = 0.020], and younger at study [27.2 vs. 32.2, t(90) = 5.29, p < 0.001] than the other half who were tested/assumed they were fertile due to previous pregnancies.

FIG. 1.

Fertility testing and awareness of fertility status among all survivors (N = 92).

Table 2.

Potential Barriers to Fertility Testing: What Are the Reasons Why You Have Not Pursued Fertility Testing?

| n | %a | |

|---|---|---|

| I did not think about it | 19 | 42.2 |

| Costs | 11 | 24.4 |

| I have no access to services/don't know how and where to get tested | 10 | 22.2 |

| I planned on getting tested when I'm in a committed relationship | 9 | 20.0 |

| I planned on getting tested when I'm older | 8 | 17.8 |

| I do not want kids anyway | 7 | 15.6 |

| I would be afraid of the results | 6 | 13.3 |

| I have assumed due to my treatment that I am infertile (BMT). Also my wife has impairment in her fertilityb | 1 | 2.2 |

| If I get pregnant okay; if not and we decided we want to raise children, we will adoptb | 1 | 2.2 |

| My gynecologist said I will not know until I start trying to conceiveb | 1 | 2.2 |

| I'm not ready to start trying to have children yetb | 1 | 2.2 |

| I would be uncomfortable with the testing itself | — | — |

| Spiritual beliefs | — | — |

| Embarrassment | — | — |

| I worry what my friends/family would think | — | — |

| I don't think I could be at risk | — | — |

Percentage refers to n = 45 (i.e., all survivors who did not have formal testing), survivors were able to check all categories that applied to them.

Categories were added by survivors.

Fertility-related uncertainty and concerns

Survivors reported relatively low levels of fertility-related uncertainty, given an average score of 1.07 (potential range: 0–3). However, survivors without children reported considerably higher uncertainty than those who had children (d = 0.72), and survivors who wanted (additional) children reported higher uncertainty than those who did not (d = 0.50; Table 1). Uncertainty also differed by beliefs, indicating that survivors who believed they were at risk reported the highest levels of uncertainty (d = 0.79–2.40; Table 1).

Fertility-related concerns were moderate (M = 2.56, potential range: 1–5), and significantly higher among those without children (d = 0.64), those who wanted (additional) children (d = 1.26), and those who believed they were at risk (d = 0.72/1.25; Table 1).

Survivors without children

Fifty-two survivors (56.5%) were without biological children, of whom 23.1% (n = 12) reported not wanting children. Responses to open-ended questions revealed this was because of worries about their own health or passing on cancer to an offspring. Most survivors (82.7%, n = 43/52) were unaware of their fertility status, while only 26.9% (n = 14) believed to be at risk. Half of survivors would pursue fertility testing if offered (n = 25, 48.1%), 30.8% (n = 16) indicated maybe, and 3.8% (n = 2) would decline. Levels of uncertainty varied, such that partnered survivors without children were more uncertain than singles (d = 0.79). Fertility-related concerns differed by whether survivors wanted children or not (d = 1.65; Table 1).

Infertility and romantic relationships

Twenty-five percent (n = 23) reported some impact of (potential) infertility on romantic relationships (negative only: n = 10, 10.9%; positive only: n = 6, 6.5%, and both: n = 7, 7.6%). Thus, 18.5% of survivors indicated a negative impact (n = 17), such as feelings of pressure on the relationship, fights, frustration, concerns, or breakups. Not being able to have children was experienced as not being able to “provide” within a relationship. One survivor even listed infertility as the reason not to date: “I don't think any guy will want to date me after they find out I'm infertile, so I don't put myself out there” (female brain tumor survivor, aged 25, diagnosed at age 15). Three survivors described trying to get pregnant as a “difficult journey,” being stressful, and related to frustration/pain due to repeated negative results (i.e., not getting pregnant and miscarriages). Yet, all three of them had children eventually. Almost all survivors reporting a negative impact were in a relationship/married (82.4%, n = 14/17), while about half had children (58.8%, n = 10/17), underlining the varying effects that (potential) infertility may have over time. Among the 10 survivors reporting negative impact only, most (70.0%, n = 7/10) were aware of their fertility status (fertile: n = 4 and infertile/impaired: n = 3).

Thirteen survivors (14.1%) reported a positive impact. Examples included having more open communication with their partners and being happy without children or with adoption. Particularly, support/understanding from partners was described as bringing them closer/strengthening the relationship. Most survivors, who reported a positive impact only, were partnered/married (83.3%, n = 5/6), while equal portions had children or were aware of their fertility status (50.0%, n = 3/6 respectively).

Discussion

Building upon and extending previous research, this study provided an overview of fertility-related perceptions and the impact of (potential) infertility on romantic relationships among adult childhood cancer survivors. While knowledge about infertility risk secondary to cancer treatment was common, fertility testing and awareness of their own fertility status were not. Fertility-related uncertainties and concerns were high in certain subgroups, but may become stressful for those who discover they are infertile in the future (or unexpectedly experience POI). Most survivors were not averse to fertility testing, suggesting that routinely addressing fertility and offering testing should be routine aspects of survivorship care.

It is promising that the majority of survivors reported knowing about infertility as a potential late effect of childhood cancer treatment. However, less than half recalled this information being given at diagnosis/during treatment, which aligns with previous research.4 Yet, this study specified that most brain tumor survivors (but no leukemia/lymphoma survivor) reported never having heard about infertility risk, although reasons for this lack of knowledge remain unclear. Perhaps, neurocognitive impairment, a common burden among brain tumor survivors,28 affects awareness of late effects. In addition, discussing infertility may not be a primary concern among providers across the cancer continuum, as many of these patients are not treated with highly gonadotoxic treatments (e.g., alkylating agents and pelvic radiation). Still, their treatment may have caused central hypogonadism, and potential fertility problems should be discussed with these survivors too.

In line with previous research,10,17,18 survivors' fertility-related beliefs differed from what they had been told, as only 30.8% of survivors who had been told they may be at risk, believed it. Nevertheless, many survivors indicated being unsure about what to believe. More importantly, although the majority of survivors knew about infertility risk, about half were unaware of their own fertility status. Such low rates have been reported previously,9–11 and this study showed that such lack of awareness does not occur due to ambiguous/unclear test results, but because survivors have never been tested (Fig. 1). Untested survivors were more often diagnosed in childhood (age <13), brain or solid tumor survivors, or younger. Underlying reasons for these findings remain speculative. Survivors may not have been involved in discussions about late effects at diagnosis or lack certain cognitive capacities (i.e., those young at diagnosis and brain tumor survivors), or they are less advanced in family planning (i.e., younger survivors). Importantly, this study demonstrated that survivors were not averse to fertility testing. Only seven survivors indicated that they did not pursue testing in the past due to fear of the results, and two would decline testing if offered.

Fertility-related uncertainties and concerns about reproductive potential were low to moderate, but many survivors may have not begun family planning, and uncertainties or concerns may arise in the future. Thus, it is unsurprising that partnered survivors without children reported much higher fertility-related uncertainty than singles. All other identified differences (e.g., higher concern among those wanting children) were intuitive, but effects were large (up to d = 2.4), underlining the potentially diverse nature/impact of fertility-related problems. Interestingly, fertility-related concerns were much lower than reported for the sample in which the RCAC was developed (M = 2.56 vs. M = 3.59, t = −3.56, p < 0.01; d = 0.87). That sample included survivors of similar age to ours, but diagnosed up to the age of 34 (when many patients may already anticipate own family plans) with types of cancer more directly affecting sexuality/fertility (e.g., breast cancer). This might explain the difference in overall scores, while subgroups reporting higher concern in this study were similar to the RCAC sample (Table 1), also highlighting the need for more research among childhood cancer survivors.

Unlike among infertile, but otherwise healthy, couples, differences between male and female survivors were not found. However, for almost all survivors, infertility was not confirmed (i.e., 9% reported test results indicating infertility), and only one-third believed they were at risk and reported the highest uncertainty and concerns. Thus, although concerns regarding their reproductive capacity may not be high currently, they may rise in the future if survivors encounter fertility problems. Future research should also compare survivors' emotional reactions after confirmed infertility to those of infertile, but otherwise healthy individuals, as it was hypothesized that infertility after cancer may be experienced as “insult added to injury.”29

The perceived impact of (potential) infertility on romantic relationships was sizeable at almost 20% (negative impact). Based on qualitative studies,12 higher rates may be expected, but participants could be less likely to write about such issues, as opposed to interviews/focus groups that might elicit examples/in-depth discussions. Nevertheless, the reported examples (e.g., frustration, fights, and open partner communication) were similar to those reported in qualitative studies,12,17,21,23 and the impact may be greater if survivors find out they are infertile in the future. Importantly, reports of negative/positive impact seemed unrelated to current relationship status or having children, underlining the varying effects of potential infertility over time. Among survivors who only reported positive impact, half had children and the other half did not, which may challenge the perception that having children is a universal life goal and could alleviate fertility-related hardship on romantic relationships. Yet, quantifying the prevalence of a negative/positive impact of infertility on romantic relationships and potential changes over time requires more research.

Although this study presents insight into fertility-related outcomes among childhood cancer survivors, firm conclusions are restricted by the limited, yet reasonably sized sample recruited at a single pediatric center. Therefore, replication is needed, as well as examinations over time exploring survivors' information-seeking behaviors, timing of fertility testing, active family planning, and/or use of reproductive assisted technologies to examine the potential impact of confirmed infertility (or resolved worries). In this study, few differences regarding background/cancer-related factors were identified, which might be a power issue requiring further exploration. Future studies may also benefit from confirming fertility-related discussions/testing through medical chart reviews, rather than exclusively relying on self-report.

Overall, this study underlines that (potential) infertility should be addressed by providers as part of routine survivorship care, a need that has been voiced previously.30 Limited awareness of fertility status, while being open to fertility testing, warrant routine fertility-related discussions with survivors. Importantly, even if uncertainties and concerns may be low at a group level, certain survivors (e.g., those wanting children, believing to be at risk, and partnered) can experience difficulty. Medical professionals should refer those survivors to psychosocial providers or organizations that can offer support. We want to emphasize that infertility, along with all other potential late effects, should be discussed with any survivor, while fertility testing should be offered, yet not be obligatory. Thereby, providers should realize that addressing fertility and offering testing in survivorship care can serve several purposes, such as educating survivors about risk, raising awareness of potential changes in fertility status as survivors (especially females) become older, offering guidance on the use of contraceptives and sexual health, discussing alternatives to biological parenthood, offering a time frame for potential fertility preservation post-treatment, and/or resolving worry.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by an intramural grant from the Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus Ohio (V.L.) and a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS; U1TR001070). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCATS or National Institutes of Health.

Disclaimer

Parts of the data presented here were also part of a podium presentation at the World Congress of the International Psycho-Oncology Society (IPOS) in Berlin, Germany (August, 2017).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skinner R, Wallace WHB, Levitt GA; UK Children's Cancer Study Group Late Effects Group. Long-term follow-up of people who have survived cancer during childhood. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:489–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chemaitilly W, Cohen LE. Diagnosis of endocrine disease: endocrine late-effects of childhood cancer and its treatments. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;176:183–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohmann C, Borgmann-Staudt A, Rendtorff R, et al. Patient counselling on the risk of infertility and its impact on childhood cancer survivors: results from a national survey. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2011;29:274–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klosky JL, Anderson LE, Russell KM, et al. Provider influences on sperm banking outcomes among adolescent males newly diagnosed with cancer. J Adol Health. 2017;60:277–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dorp W, Mulder RL, Kremer LC, et al. Recommendations for premature ovarian insufficiency surveillance for female survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: a report from the international late effects of childhood cancer guideline harmonization group in collaboration with the PanCareSurFup consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3440–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.COG. Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers. Version 4.0. 2013. Accessed September1, 2017 from: www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/LTFUGuidelines_40.pdf

- 8.Salih SM, Elsarrag SZ, Prange E, et al. Evidence to incorporate inclusive reproductive health measures in guidelines for childhood and adolescent cancer survivors. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28:95–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zebrack BJ, Casillas J, Nohr L, et al. Fertility issues for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13:689–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frederick NN, Recklitis CJ, Blackmon JE, Bober S. Sexual dysfunction in young adult survivors of childhood cance. Peds Blood Cancer. 2016;63:1622–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehmann V, Keim MC, Nahata L, et al. Fertility-relatd knowledge and reproductive goals in childhood cancer survivors: short communication. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:2250–2253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson J, Jervaeus A, Lampic C, et al. ‘Will I be able to have a baby?’ results from online focus group discussions with childhood cancer survivors in sweden. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:2704–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barlevy D, Wangmo T, Elger BS, Ravitsky V. Attitudes, beliefs, and trends regarding adolescent oncofertility discussions: a systematic literature review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2016;5:119–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nieman CL, Kinahan KE, Yount SE, et al. Fertility preservation and adolescent cancer patients: lessons from adult survivors of childhood cancer and their parents. In: Woodruff TK, Snyder KA. (Eds). Oncofertility: fertility preservation for cancer survivors. New York: Springer; 2007; pp. 201–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reinmuth S, Liebeskind A, Wickmann L, et al. Having children after surviving cancer in childhood or adolescence—results of a berlin survey. Klin Padiatr. 2008;220:159–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green D, Galvin H, Horne B. The psycho‐social impact of infertility on young male cancer survivors: a qualitative investigation. Psychooncology. 2003;12:141–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawshaw M, Sloper P. ‘Swimming against the tide’–the influence of fertility matters on the transition to adulthood or survivorship following adolescent cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2010;19:610–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benedict C, Shuk E, Ford JS. Fertility issues in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2015;5:48–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilleland Marchak J, Elchuri SV, Vangile K, et al. Perceptions of infertility risks among female pediatric cancer survivors following gonadotoxic therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;37:368–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J, Mersereau JE. A pilot study about female adolescent/young childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about reproductive health and their views about consultation with a fertility specialist. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13:1251–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehmann V, Grönqvist H, Engvall G, et al. Negative and positive consequences of adolescent cancer 10 years after diagnosis: an interview-based longitudinal study in Sweden. Psychooncology. 2014;23:1229–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis P, Jordens CF, Mooney-Somers J, et al. Growing up with cancer: accommodating the effects of cancer into young people's social lives. J Peds Oncol Nurs. 2013;30:311–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson AL, Long KA, Marsland AL. Impact of childhood cancer on emerging adult survivors' romantic relationships: a qualitative account. J Sex Med. 2012;10:65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hjelmstedt A, Andersson L, Skoog‐Svanberg A, et al. Gender differences in psychological reactions to infertility among couples seeking IVF‐and ICSI‐treatment. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:42–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrews FM, Abbey A, Halman LJ. Stress from infertility, marriage factors, and subjective well-being of wives and husbands. J Health Soc Behav. 1991;32:238–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehmann V, Tuinman MA, Keim MC, et al. Psychosexual development and satisfaction in long‐term survivors of childhood cancer: neurotoxic treatment intensity as a risk indicator. Cancer. 2017;123:1869–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorman JR, Su HI, Pierce JP, et al. A multidimensional scale to measure the reproductive concerns of young adult female cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:218–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulhern RK, Merchant TE, Gajjar A, et al. Late neurocognitive sequelae in survivors of brain tumours in childhood. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:399–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schover LR. Psychosocial aspects of infertility and decisions about reproduction in young cancer survivors: a review. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:53–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crawshaw M. Psychosocial oncofertility issues faced by adolescents and young adults over their lifetime: a review of the research. Hum Fertil. 2013;16:59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1988 [Google Scholar]