Abstract

The appearance of perineuronal nets (PNNs) represents one of the mechanisms that contribute to the closing of sensitive periods for neural plasticity. This relationship has mostly been studied in the ocular dominance model in rodents. Previous studies also indicated that PNN might control neural plasticity in the song control system of songbirds. To further elucidate this relationship, we quantified PNN expression and their localization around parvalbumin interneurons at key time-points during ontogeny in both male and female zebra finches, and correlated these data with the well-described development of song in this species. We also extended these analyses to the auditory system. The development of PNN during ontogeny correlated with song crystallization although the timing of PNN appearance in the four main telencephalic song control nuclei slightly varied between nuclei in agreement with the established role these nuclei play during song learning. Our data also indicate that very few PNN develop in the secondary auditory forebrain areas even in adult birds, which may allow constant adaptation to a changing acoustic environment by allowing synaptic reorganization during adulthood.

Keywords: vocal learning, perineuronal nets, parvalbumin, sensitive period, song system, ontogenesis

1. Introduction

Learning-related neuroplasticity is expressed at its highest level during ontogeny and supports progressive shaping of the adult brain. Extensive neurogenesis and synaptic organization take place during this plastic developmental period and are shaped by the environment. These neurobiological processes are fundamental for the normal development of brain and behaviour in both humans and animals. At the end of development, neural plasticity and new learning decrease drastically but the underlying mechanisms involved remain poorly understood.

It has been suggested that the appearance of perineuronal nets (PNN) is one of the mechanisms that contribute to the closing of sensitive periods for neural plasticity and associated learning [1]. In mammals, an increased PNN expression in the somatosensory visual cortex correlates with the end of the sensitive period for visual [2–7] and other aspects of learning [8–10]. These PNN are aggregates of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan chains (CSPGs) associated with hyaluronic acid and tenascin R that form a scaffold generally surrounding GABAergic interneurons expressing the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin (PV) [2,11]. They develop in an experience-dependent manner at the end of the sensitive period for visual learning in the visual cortex [6] and constitute a physical barrier precluding new synaptic contacts [2]. On another hand, the development of PV interneurons usually marks the onset of sensitive periods for somatosensory learning, while formation of PNN around them marks the end of such sensitive periods [2,3].

The song of oscines (songbirds) is learned during development by imitation of a conspecific tutor, a rare feature only observed in a few groups of mammals (humans, some bats, whales and elephants) and birds (songbirds, some hummingbirds and parrots) [12]. Vocal learning in songbirds is associated with sensitive periods for sensory learning (song memorization) and sensorimotor learning (vocal practice) that finally lead to the crystallization of the mature adult song [13,14]. The sensorimotor stages of song learning (subsong, plastic song and crystallized song) correspond to human speech learning progressing from babies' babbling to grammatically correct language [15–17].

The neural network underlying these processes is analogous if not homologous. In songbirds, the interconnected brain nuclei involved in song learning and production is called the song control system. It comprises two main pathways. The vocal motor pathway, which connects HVC (previously high vocal centre, now used as a proper name) directly to the premotor nucleus RA (robustus nucleus of the arcopallium), is similar to the connection between Broca's area and the laryngeal cortex in humans. HVC and RA are also indirectly connected through Area X from the basal ganglia and LMAN (lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium) that form the anterior forebrain pathway (AFP) which corresponds to the corticostriatal motor loop in humans [17–19]. These functional and anatomical similarities make songbirds a unique model to study brain mechanisms underlying vocal learning.

In zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata), sensory learning (template memorization) takes place between 25 and 65 days post-hatching (dph) [12,13,16]. Sensorimotor learning starts around 30 dph in zebra finches and thus overlaps with sensory learning. At that time, the song is still variable but it will progressively match the memorized template through a feedback process [15] to reach (around 90 dph) a fully mature crystallized song that will remain stable for the rest of each individual's life.

Between hatching and 90 dph the song control nuclei HVC, RA and Area X undergo major morphological changes including global increases in volume and neuronal size, development of long distance connections and synaptic reorganization [20–22]. LMAN, which directly projects to RA and modulates song variability, increases in volume until 20 dph and then regresses later on [22]. Sex differences also appear during song learning so that HVC and RA become much bigger in males than females (Area X is essentially not visible in females) [22,23]. The connections in the AFP are established before song production begins but will be refined during song learning [20]. For example, the connection from LMAN to RA undergoes synaptic pruning that leads to a topographic reorganization [24] that is probably essential for the progressive transition from a variable to a crystallized song when the HVC to RA connection is fully established.

It was previously shown that adult male zebra finches have significantly more PNN especially around PV neurons in HVC and RA than 33-day-old juveniles and this measure in HVC was positively correlated with song stereotypy. Isolation from tutor song during development decreased numbers of PNN around PV neurons in HVC [25]. Adult males who sing proficiently also have more PNN especially around PV neurons in HVC and RA than females who do not sing [26,27]. Moreover, adult male zebra finches who are closed-ended learners have a higher PNN density in most song control nuclei compared with other songbird species able to modify their song during adulthood [28]. Together these correlations suggest a causal relationship between high PNN expression in the song control system and decreased neural and song plasticity. Nevertheless, the specific time-course of PNN development across developmental song learning is not known. To elucidate this question, we quantified here PNN expression and their localization around PV interneurons throughout ontogeny (every 10 days from 10 to 60 dph then at 90 and 120 dph) in four song control nuclei and four auditory nuclei in both male and female zebra finches and correlated these data with the well-described development of song and of song control nuclei in this species. The results allow us to draw clear links between PNN appearance in specific brain regions and the time course of song learning. Our findings suggest that the function of PNN expression might differ among different song control nuclei, providing specific empirical foundation for future experimental manipulations of PNN expression.

2. Material and methods

(a). Subjects and tissue collection

Forty-six male and 32 female zebra finches (T. guttata) were raised in a common indoor aviary containing nesting material, along with their parents and a large group of conspecifics on a 13 L : 11 D cycle with food and water ad libitum. Brains were collected from eight developmental ages (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 90 and 120 dph; 3–6 females and 4–7 males/group; see figures to determine the actual number of individual data points in each case) after perfusion under anaesthesia (0.5 ml Nembutal at 0.6 mg ml−1) with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) followed by paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS). After 24 h postfixation and cryoprotection in 30% sucrose in PBS, brains were cut on a cryostat in 30 µm coronal sections that were collected in six series of four wells.

(b). Immunohistochemistry

One series from each bird was stained by double-label immunohistochemistry for PV and perineuronal nets as previously described [25,27,28]. Free-floating sections were incubated in a mouse monoclonal anti-chondroitin sulfate (1 : 500) specific for the glycosaminoglycan portion of the CSPGs that are main components of the PNN and a polyclonal rabbit anti-PV (1 : 1000) and visualized using Alexa-coupled secondary antibodies (see electronic supplementary material for details).

One series generally contained at least four sections within each region of interest (ROI). However, this was not the case for younger birds and some females. For those birds a second full series was consequently stained to ensure appropriate sampling of all ROIs in most subjects. Even with this second series of sections, song control nuclei could not be detected in all subjects at 10 dph, resulting in a smaller number of data point at this age. Sections from the first series were stained in three batches each containing individuals from all age groups to prevent any possible batch effect. Sections for the second series were stained in one batch. No statistical differences between the two staining series could be detected and analysis of data including or excluding series 2 led to similar statistical results. Only global analyses including all subjects and sections will thus be presented.

(c). Parvalbumin and perineuronal net quantifications

Staining was bilaterally quantified in the four main song control nuclei (HVC, RA, Area X and LMAN) and in four auditory nuclei: CMM (caudomedial mesopallium), NCM (caudomedial nidopallium), Field L complex that are directly or indirectly connected to HVC [29,30] and in NCC (caudocentral nidopallium), a multisensory integrative forebrain area processing acoustic signals and their use in mate choice [31]. Detection of the ROIs was based on the bright PV and/or PNN staining background of these areas except for NCM and NCC which were located based on the zebra finch atlas [32]. NCM is a large telencephalic region extending rostro-caudally from the caudal end of Field L to the caudal edge of the medial telencephalon. NCC is similarly located but lateral to NCM. In this area, pictures were always taken dorsal to the arcopallium at the level of RA, between the caudal end of HVC and the rostral end of RA.

Photomicrographs were acquired bilaterally, with a Leica fluorescence microscope with a 40× objective and fixed settings, in 3–4 sections equally spaced in the rostro-caudal axis for each ROI. The numbers of PV-positive cells (PV), of cells surrounded by PNN (PNN) and of PV-positive cells surrounded by PNN were counted in all photomicrographs with ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih/ij) as previously described [28].

For each ROI, PV and PNN were quantified as density mm−2 and as total number/nuclei. Additionally, we calculated the % PV surrounded by PNN (%PVwithPNN) and the % PNN surrounding PV (%PNNwithPV) (see electronic supplementary information for details). Pictures were also acquired at 5× magnification (within one or two full series) for sections containing HVC, RA or Area X to quantify their volume as previously described [28].

All counting and measurements were done blind to the age and sex of the subjects, except for Area X that does not exist in females in which counts were obtained in an equivalent area located at the same neuroanatomical coordinates.

(d). Statistics

All data were analysed independently for each ROI using a two-way ANOVA with sex (n = 2) and age (n = 8) as independent factors. Significant interactions or age effects were further analysed using Tukey's post hoc tests. Significance level was set at p < 0.05. Some statistical tendencies at p < 0.10 are also shown when important for data interpretation. Results of all ANOVAs (F and p) are reported in electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S2.

3. Results

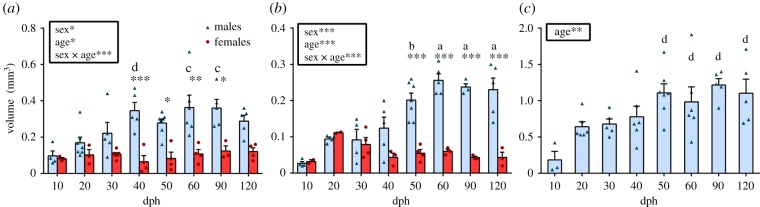

(a). Song control nuclei volume

The volume of HVC and RA increased significantly with age and was different between sexes. Post hoc analysis of the significant sex by age interaction confirmed that the increase appeared in males only, starting at 40 dph in HVC and 50 dph in RA, with the sex difference appearing at the same age (figure 1a,b). Similarly, the volume of Area X increased with age in males starting at 50 dph (figure 1c). The maximum volume was reached at 40 dph in HVC and at 50 dph in RA and Area X, (figure 1a–c) as previously reported [22].

Figure 1.

(a) HVC, (b) RA and (c) Area X volumes of males (blue) and females (red) across ages 10–120 dph. Results of the ANOVAs are summarized in the insets. If a significant sex by age interaction was detected, significant sex differences within age groups as determined by Tukey's post hoc tests are shown as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Letters indicate significant (p < 0.05) age differences within males only as follows: a, different from 10–40 dph; b, different from 10–30 dph; c, different from 10–20 dph; d, different from 10 dph. Bars represent means ± s.e.m. but all individual values are also plotted.

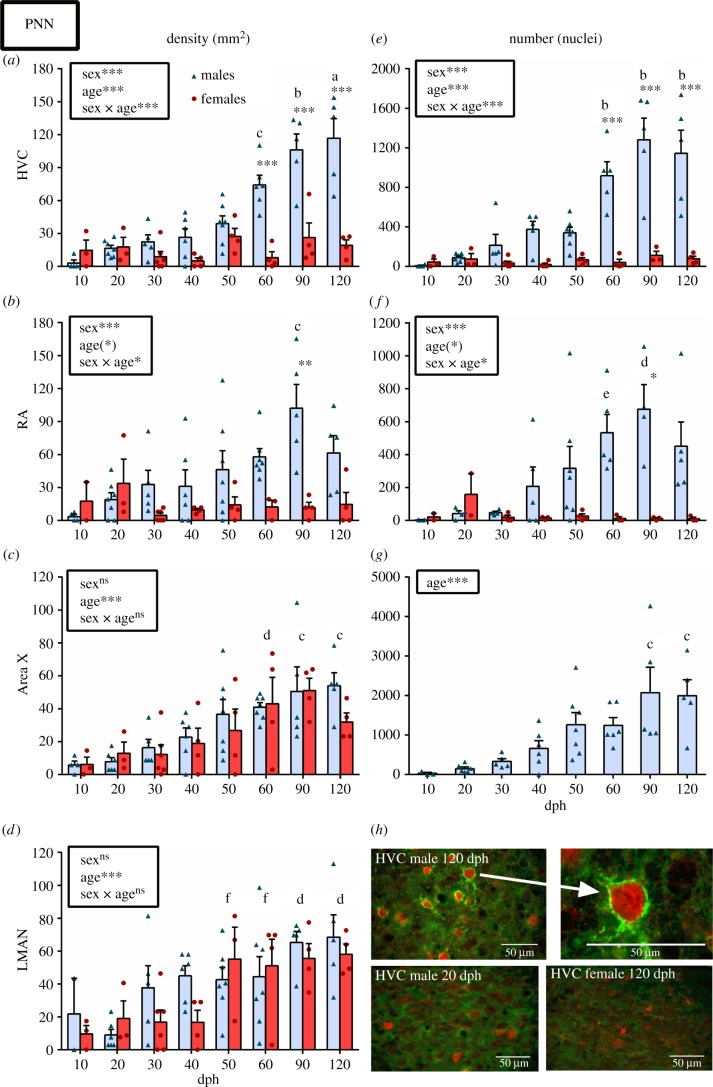

(b). Perineuronal nets increase around parvalbumin cells in the vocal motor pathway after the end of sensory learning

In HVC, the density of PNN+ cells increased progressively with age, and this increase was significant from 60 dph until adulthood (90–120 dph) in males but not in females (figure 2a). Similarly, the total number of PNN in the nucleus increased significantly from 60 dph in males only and the plateau was reached at 90 dph (figure 2e). In both measures, a significant sex difference was present from 60 till 120 dph (figure 2a,e). In RA, a similar pattern of progressive PNN increase (density and number/nuclei) was detected in males, but the significant sex difference appeared at 90 dph only (see figure 2b,f).

Figure 2.

(a–d) PNN density and (e–g) number/nuclei in the song control system of males (blue, light grey in print) and females (red, dark grey in print) across ages 10–120 dph. Statistical results of the ANOVA are summarized in the insets. If a significant sex by age interaction was detected, significant sex differences within age groups as determined by Tukey's post hoc tests are shown as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, (*) p < 0.10. Letters indicate significant (p < 0.05) age differences within males only (when interaction is significant) or among all birds (when a main effect of age without interaction is found) as follows: a, different from 10–60 dph; b, different from 10–50 dph; c, different from 10–40 dph; d, different from 10–30 dph; e, different from 10 dph; f, different from 20 dph. (h) Representative photomicrographs of PV+PNN double staining in HVC of an adult male (upper left), a 20 dph males (down left), an adult female (down right) and higher magnification of a PV cell surrounded by PNN in the adult male. Bars represent means ± s.e.m. but all individual values are also plotted. (Online version in colour.)

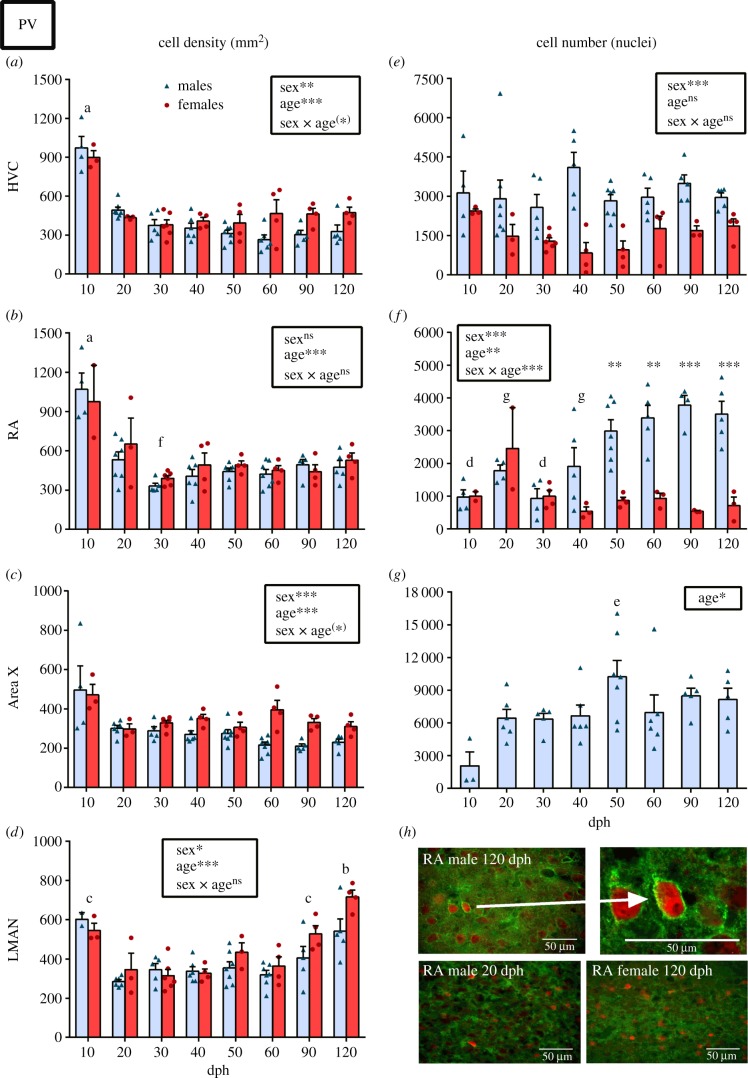

In parallel, we observed a significant drop of the density of PV+ cells in HVC and RA after 10 dph (figure 3a,b). However, the total number of PV+ cells in the entire nucleus was not affected by age in HVC (figure 3e) and it significantly increased from 50 dph on in the RA of males only (figure 3f). In HVC, whereas females had overall a higher density of PV+ cells, males had a higher number of PV in the entire nucleus (figure 3a–e). This opposite sex difference relates to the large sex difference in the volume of this nucleus appearing around 40 dph. In RA, no sex difference was detected in the density of PV+ cells, but males also had more PV than females in the entire nucleus (figure 3b,f).

Figure 3.

(a–d) PV density and (e–g) number/nuclei in the song control system of males (blue, light grey in print) and females (red, dark grey in print) across ages 10–120 dph. Statistical results of the ANOVA are summarized in the insets. If a significant sex by age interaction was detected, significant sex differences within age groups as determined by Tukey's post hoc tests are shown as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, (*) p < 0.10. Letters indicate significant (p < 0.05) age differences within males only (when interaction is significant) or among all birds (when a main effect of age without interaction is found) as follows: a, different from 20–120 dph; b, different from 20–90 dph; c, different from 20–60 dph; d, different from 50–120 dph; e, different from 10 dph; f, different from 20 dph; g, different from 90 dph. (h) Representative photomicrographs of PV + PNN double staining in RA of an adult male (upper left), a 20 dph males (down left), an adult female (down right) and higher magnification of a PV cell surrounded by PNN in the adult male. Bars represent means ± s.e.m. but all individual values are also plotted. (Online version in colour.)

Interestingly, the percentage of PV cells surrounded by PNN increased following a pattern very similar to the increase of PNN density and number/nuclei in both HVC and RA. In HVC, this percentage was significantly increased from 60 until 120 dph (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1a), while in RA, the increase was significant from 60 until 90 dph but no longer at 120 dph (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1b). This suggests that, in the vocal motor pathway of males, a large amount of PNN starts developing specifically around PV+ interneurons when the sensory learning period ends and these PNN continue to increase until the end of the sensorimotor period (90 dph) when PNN density, PNN/nuclei and the percentage of PV+ neurons with PNN reach a plateau.

(c). Perineuronal nets development in the anterior forebrain pathway

In Area X and LMAN the density of PNN increased with age in both males and females, starting at 60 dph in Area X (figure 2c) and at 50 dph in LMAN (figure 2d). Interestingly, no sex difference was detected in Area X or LMAN despite the fact that Area X is not visible in females and counts were made in an anatomically equivalent area. It should also be noted that the average density of PNN in LMAN of males already reached a level similar to 50–60 dph at 30–40 dph (figure 2d), which was not the case for females. This is probably why the statistical significance of the age effect (in the absence of a significant interaction) appeared only at 50 dph when both males and females reached the same level of PNN density. In Area X, the total number of PNN also increased with age in males but the effect only became significant at 90 dph only (figure 2g). Total numbers of PNN could not be calculated for the female Area X nor for LMAN in both sexes because boundaries of these ROI could not be delineated.

As seen in HVC and RA, the density of PV+ cells dropped significantly after 10 dph in Area X and LMAN (figure 3c,d). Interestingly, whereas the PV density remained stable at later ages in HVC, RA and Area X, it increased significantly in LMAN at 90 dph and even further at 120 dph. The total number of PV+ cells in the Area X of males followed a different pattern with a main effect of age essentially due to the 50 dph males that had more PV than 10 dph males (figure 3g). The percentage of PV surrounded by PNN in Area X also increased with age, but the effect became significant only at 90 dph (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1c) i.e. when the total number of PNN increased. In LMAN a progressive increase in this measure was present but the percentage was significantly different only between the 60 and 120 dph birds versus the 20 dph birds (a tendency was nevertheless observed at 90 dph: p = 0.0506).

As in HVC and RA, the PNN density, total PNN/nuclei and percentage of PV neurons surrounded with PNN in the AFP were thus increasing with age but in both males and females instead of males only, and the PNN development seemed to occur earlier in LMAN (especially in males). Nevertheless, as in the vocal motor pathway, PNN development starts near the end of the sensitive period for sensory learning and takes place mostly during the sensorimotor period for song learning.

(d). Percentage of perineuronal nets located around PV+ interneurons varies between sexes

In HVC and RA, the percentage of PNN surrounding PV was not affected by age but differed between sexes. Overall the majority of PNN were located around PV cells and this localization was more prominent in males than in females (HVC: 79% versus 61%; RA: 85% versus 49%; see electronic supplementary material, figure S2a–b). By contrast, in Area X, a higher proportion of PNN were surrounding PV in females (72%) than in males (50%) (see electronic supplementary material, figure S2c). In LMAN there was no sex difference affecting this percentage but it was lower at earlier ages (10–20 dph) and significantly higher at 120 dph (73%) compared with 20 dph birds (see electronic supplementary material, figure S2d). Taken together, these data indicate that PNN stabilize the connectivity of different cell types (PV-positive and others) depending on the sex and the nucleus considered but this association with different cell types does not change with age except in LMAN.

(e). Perineuronal nets and parvalbumin expression in auditory nuclei during development

Overall, the density of PNN in the auditory nuclei CMM, NCM and NCC was very low compared with densities observed in the four main song control nuclei. In the majority of birds, the density was smaller than 20 PNN mm−2 and the mean of each group rarely exceeded 10 PNN mm−2 (see electronic supplementary material, figure S3b–d). This density was 10 times higher in HVC and RA and five times higher in Area X and LMAN in adult males. The PNN density in these three nuclei did not change as a function of age or sex (see electronic supplementary material, figure S3b–d), nor did the percentage of PV+ cells surrounded by PNN (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1f–h). PNN in CMM, NCM and NCC are thus unlikely to be involved in the song crystallization process. In contrast, a high density of PNN was found in Field L and it significantly increased with age (see electronic supplementary material, figure S3a for detail of post hoc tests comparing ages). As observed in Area X and LMAN, this increase occurred in both males and females.

The densities of PV+ cells in CMM, NCM and NCC were comparable with the densities observed in song control nuclei and they were significantly affected by the sex of the subjects. Females had a slightly higher PV density in CMM and NCM (see electronic supplementary material, figure S4b–c; only in older ages in the latter case was there a significant interaction of sex by age) whereas males had slightly more PV in NCC (see electronic supplementary material, figure S4d). This density of PV cells also increased with age in NCM (120 dph had more PV mm−2 than 10–50 dph birds; electronic supplementary material, figure S4c) and CMM in which 10 dph had fewer PV mm−2 than all the other age groups (see electronic supplementary material, figure S4b). In NCM, the interaction showed that this age effect was partly due to 120 dph females who had a significantly higher PV density than 20–60 dph males (statistics not shown in the graph). The low density of PNN in these nuclei was reflected in the percentage of PV surrounded by PNN that was lower than 3% in most groups and was not affected by age or sex (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1f–h).

The density of PV+ cells was also affected by age in Field L essentially because it was much higher at 10 dph than in all older age groups (see electronic supplementary material, figure S4a). Note, however, that in the brain of 10 dph birds Field L was not clearly discernible as it is in older birds. We therefore quantified photomicrographs taken at the same location within the telencephalon, but corresponding results should be taken cautiously. Counts at 10 dph could relate to another adjacent area. Even ignoring the 10 dph data, the percentage of PV neurons with PNN increased with age in parallel to the PNN density reaching maximal levels around 50 dph (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1e for detail of post hoc tests) in the absence of any sex difference.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that in the four main song control nuclei PNN and their localization around PV interneurons generally start increasing around 50–60 dph, an age that corresponds to the end of the sensory phase of vocal learning when the tutor song has been memorized. The maximum PNN expression is reached later, at an age that varies between nuclei. A sex difference in PNN expression and/or colocalization with PV also develops, starting at 60 dph in HVC and RA (which are involved in song production), but not in Area X and LMAN (which play a role in song learning and variability).

A similar pattern of changes with age was observed in the auditory Field L, but increases were observed earlier (first increase at 30 dph and plateau at 50 dph) and were not associated with a sex difference. Surprisingly, however, in the other telencephalic auditory areas, few PNN were detected and their density did not change as a function of age, suggesting that these nuclei possibly retain their plasticity in adulthood.

(a). Perineuronal nets increase in the motor pathway corresponds to the end of the sensorimotor-sensitive period and song crystallization

In HVC and RA, the largest increase in PNN expression started at the end of the sensitive period for sensory learning (60 dph) and reached a plateau at the end of the sensorimotor learning period (90 dph). This temporal pattern is consistent with a role of PNN in song crystallization. As the majority of PNN are located around GABAergic inhibitory interneurons expressing PV [33] and PNN are known to increase fast spiking activity of these neurons [34,35], song crystallization could result from an increased inhibition within HVC, resulting in a decreased synaptic plasticity [2]. A higher neural inhibition in HVC indeed correlates with song stability in adult zebra finches [36]. In RA the density of PNN and the percentage of PV neurons with PNN followed a similar pattern of increase although absolute numbers were smaller and the peak observed at 90 dph was followed by a small (non-significant) decrease at 120 dph. The PNN density and the percentage of PV neurons with PNN were thus maximal at 90 dph in both HVC and RA, suggesting a clear link between PNN in these nuclei and song crystallization that is completed at 90 dph.

In both HVC and RA, males had a higher proportion of PNN around PV interneurons (more than 80%) than females (60% in HVC, 50% in RA). In the female HVC and RA, PNN thus develop around different neuronal types or around interneurons expressing different calcium-binding proteins such as calretinin or calbindin. It is nevertheless likely that PNN are expressed mainly around GABAergic interneurons as shown in mammals [35,37]. Together with the higher density of PNN in males, this suggests a differential role of PNN in the vocal motor pathway of the two sexes in relation with the fact that females do not sing and only produce calls [12].

(b). Perineuronal nets increase in the anterior forebrain pathway corresponds to the progressive decrease of song variability during the sensorimotor period

In agreement with previously published studies on adult zebra finches [26,27], no sex difference in the PNN density could be detected in Area X and LMAN throughout development. This is particularly surprising for Area X because this nucleus is not visible in Nissl-stained sections of females and quantification was made here in the corresponding part of the basal ganglia. In males, Area X was discernible based on a higher background staining for PV and a higher density of PNN compared to the rest of the basal ganglia. These differences were not clearly visible in females although PV background density tended to be higher in the lateral part of the basal ganglia (but no shape reminiscent of Area X was detectable) and PNN density tended to be higher in the female ‘Area X’ than in the rest of the basal ganglia. It should be noted that a recent anterograde and retrograde tract-tracing study has demonstrated that HVC in female zebra finches projects to a clearly defined cluster of cells in the basal ganglia [38]. A functional Area X might thus exist in females also.

PNN density increased significantly starting at 60 dph in Area X and 50 dph in LMAN but these changes were similar in both sexes. Here again, the beginning of this rise corresponds to the end of the sensory learning period (60 dph) but it is not followed by any major changes later in development, contrary to what is observed in the motor pathway. However, the AFP has never been associated with song memorization. Moreover, the total number of PNN in Area X continued to increase after 60 dph, in relation to the global increase in volume of the nucleus, to reach a plateau at 90 dph at end of the sensorimotor period. The development of PNN in the AFP is consequently more likely to be related to the sensorimotor than to the sensory learning stage.

Knowing that (a) LMAN plays a key role in vocal learning at early stages of sensorimotor learning [20,39], (b) song variability [13] is highest between 30 and 60 dph [23], (c) LMAN volume decreases between 20 and 50 dph in male zebra finches and no change occurs later [22] and (d) LMAN lesions between 55 and 65 dph are less effective in disturbing song production than lesions performed between 35 and 50 dph [40], it is interesting that this is the nucleus where the increase in PNN density occurred at the earliest age (around 50 dph or maybe even earlier in males). A large (though not significant, possibly due to the large number of comparisons) increase of the average PNN density (4×) and of the percentage of PV neurons with PNN (5.5×) takes place between 20 and 30 dph in the LMAN of males specifically. These measures remain relatively constant afterwards, whereas they only increase after 50 dph in females to reach male levels. This early increase of PNN in LMAN of males was not observed in Area X.

This specific timing of PNN development in LMAN and Area X suggests a delay between the synaptic maturation of these two nuclei in males only. Area X sends inhibitory projections into DLM which in turn sends excitatory projections to LMAN [13]. LMAN is known to induce song variability through its connectivity with RA [41]. LMAN activity could thus be stabilized early (30 dph) by the development of PNN in males to control the firing of the LMAN-RA projection neurons during a period of high song variability (30–50 dph). The subsequent development of PNN around PV interneurons in Area X would then progressively inhibit the excitatory action of DLM on LMAN, in turn decreasing its activity and thus song variability when the song becomes completely stereotyped. This scenario is consistent with the fact that, in males, the percentage of PNN neurons around PV in Area X (50%) and LMAN (56%) is much lower than in HVC (79%) and RA (85%), indicating that in the AFP a large portion of PNN potentially develop around neurons that are not expressing PV and are eventually projection neurons. Furthermore, PV-positive cells can also be projection neurons [42].

(c). Role of perineuronal nets in the auditory nuclei

We observed an early increase of PNN density and of the percentage of PV neurons with PNN in Field L between 10 and 30 dph. This increased expression of PNN in Field L occurs during the early steps of song memorization. Field L, as the mammalian primary auditory cortex, relays the auditory information directly to HVC but also to CMM and NCM [30]. This brain region is however processing all kinds of auditory stimuli besides species-specific vocalizations and it is difficult to imagine that plasticity in this area should decrease with age. The absence of sex differences in Field L is however in agreement with the fact that both males and females need to be able to discriminate male songs.

In the other auditory nuclei, the density of PNN was much lower (PNN density peak in males: CMM: 16.6 mm−2, NCM: 7.2 mm−2, NCC: 6.8 mm−2), as previously observed in adult male starlings [28] and adult male and female canaries (G.C., C.A.C. & J.B. 2018, unpublished data). Moreover, the density of PNN was not affected by age or sex in these regions. Either synaptic plasticity in these auditory forebrain areas is controlled by other mechanisms or it is surprisingly retained in adulthood. CMM and NCM are thought to be involved in song perception and decoding [30] and NCM could, in addition together with the vocal pathway, contain (in part) the memory of the tutor song template [43]. Neurons in Field L, CMM and NCM respond selectively to the species-specific songs during development [44–47] but CMM and NCM neurons respond in a non-predictable manner and this response continuously evolves with the acoustic environment even in adulthood which is not the case for Field L [48–51]. The relative absence of PNN in the NCM and CMM may consequently allow constant adaptation of adult zebra finches to a changing acoustic environment by providing a larger possibility of synaptic reorganization.

5. Conclusion

We demonstrate here sex-specific and age-specific changes in the expression of PNN and of PV interneurons in the song control nuclei and auditory areas of developing zebra finches that display temporal relationships with the sensory and sensorimotor phases of song development. The differences observed between nuclei suggest that each nucleus has its own timing of connectivity stabilization (sensitive period?) during which it plays one key role in the vocal learning process. These correlations raise a number of important questions. One set of questions concerns the role of PNN in song learning. Are they slowing down or inhibiting the learning process? Are they implicated in the crystallization of song? Are different nuclei differentially affected as a function of their role in song acquisition and production as suggested by differences in the temporal patterns of expression? The other type of questions relates to the mechanisms controlling PNN formation. Do they develop directly in response to physiological, in particular, hormonal changes that take place as the bird ages or are they the consequence of changes in the vocal behaviour that would feedback on the underlying brain structures?

We previously showed that the density of PNN is lower in open-ended learner species that are still able to modify their song in adulthood (canaries, starlings) than in closed-ended learner species such as the zebra finch that crystallize a song when reaching adulthood and will no longer change it during the rest of their life. This suggests that PNN development might relate to song crystallization and the developmental patterns identified here are consistent with this view. The functional significance of these correlations should now be tested by causal manipulations, in particular, experiments that would experimentally dissolve the PNN in specific brain regions and assess whether this would result in a regain of behavioural plasticity as previously shown in a number of experimental models in mammals. An initial attempt obtained mixed results: application of chondroitinase ABC dissolved the PNN in HVC, but no clear modification of song structure was detected in males kept in acoustic isolation. However, in males maintained with a female after PNN dissolution, song became more plastic: song duration decreased, and some syllables were lost while others were added [52]. We also observed some alterations of song in male canaries following application of chondroitinase ABC over HVC (G.C., C.A.C. & J.B. 2018, unpublished data). Future work will have to better characterize these changes in vocal production and learning in order to assign a specific role to PNN in each song control nuclei. The age- and nuclei-specific changes described here will clearly help formulating specific hypotheses and testing them.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Sander Raymaekers from the Laboratory of Comparative Endocrinology, Biology department, KU Leuven, Belgium (headed by Veerle Darras) for providing a few additional brain sections to complete our sampling.

Ethics

All experimental procedures were in agreement with the Belgian laws on animal experimentation and had been approved by the local Animal Care Committee (Commission d'Ethique de l'Utilisation des Animaux d'Expérience de l'Université de Liège; Protocol number 1396).

Data accessibility

All data raw data are available for review at Dryad Digital Repository (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.515n9k9) [53].

Authors' contributions

G.C., S.M.t.H., A.V.d.L. and J.B. designed the study; G.C., E.J. and S.M.t.H. collected the data; G.C, E.J. and J.B. analysed the data; G.C. and E.J. wrote the initial draft of the paper that was edited by A.V.d.L., C.A.C. and J.B.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Interuniversity Attraction Pole (IAP P7/17) to A.V.d.L., C.A.C. and J.B. C.A.C. is FRS-FNRS Senior Research Associate and G.C. is Research Fellow of the FRS-FNRS. E.J. is a FWO postdoctoral research fellow.

References

- 1.Celio MR, Spreafico R, De Biasi S, Vitellaro-Zuccarello L. 1998. Perineuronal nets: past and present. Trends Neurosci.. 21, 510–515. ( 10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01298-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karetko M, Skangiel-Kramska J. 2009. Diverse functions of perineuronal nets. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. (Wars) 69, 564–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D, Fawcett J. 2012. The perineuronal net and the control of cns plasticity. Cell Tissue Res. 349, 147–160. ( 10.1007/s00441-012-1375-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H, Xu H, Yu T, Yao J, Zhao C, Yin ZQ. 2013. Expression of perineuronal nets, parvalbumin and protein tyrosine phosphatase σ in the rat visual cortex during development and after BFD. Curr. Eye Res. 38, 1083–1094. ( 10.3109/02713683.2013.803287) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pizzorusso T, Medini P, Berardi N, Chierzi S, Fawcett JW, Maffei L. 2002. Reactivation of ocular dominance plasticity in the adult visual cortex. Science 298, 1248–1251. ( 10.1126/science.1072699) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye Q, Miao Q. 2013. long. Experience-dependent development of perineuronal nets and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan receptors in mouse visual cortex. Matrix. Biol. 32, 352–363. ( 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.04.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vorobyov V, Kwok JCF, Fawcett JW, Sengpiel F. 2013. Effects of digesting chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans on plasticity in cat primary visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 33, 234–243. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2283-12.2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gogolla N, Caroni P, Luthi A, Herry C. 2009. Perineuronal nets protect fear memories from erasure. Science 325, 1258–1261. ( 10.1126/science.1174146) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Happel MFK.12014. Enhanced cognitive flexibility in reversal learning induced by removal of the extracellular matrix in auditory cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 2800–2805. ( 10.1073/pnas.1310272111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slaker M, Churchill L, Todd RP, Blacktop JM, Zuloaga DG, Raber J, Darling RA, Brown TE, Sorg BA. 2015. Removal of perineuronal nets in the medial prefrontal cortex impairs the acquisition and reconsolidation of a cocaine-induced conditioned place preference memory. J. Neurosci. 35, 4190–4202. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3592-14.2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deepa SS, Carulli D, Galtrey C, Rhodes K, Fukuda J, Mikami T, Sugahara K, Fawcett JW. 2006. Composition of perineuronal net extracellular matrix in rat brain: a different disaccharide composition for the net-associated proteoglycans. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17 789–17 800. ( 10.1074/jbc.M600544200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams H. 2004. Birdsong and singing behavior. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1016, 1– 30 ( 10.1196/annals.1298.029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mooney R. 2009. Neural mechanisms for learned birdsong. Learn. Mem. 16, 655–669. ( 10.1101/lm.1065209) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenowitz EA. 2004. Plasticity of the adult avian song control system. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1016, 560–585. ( 10.1196/annals.1298.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brainard MS, Doupe AJ. 2000. Auditory feedback in learning and maintenance of vocal behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1, 31–40. ( 10.1038/35036205) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brainard MS, Doupe AJ. 2002. What songbirds teach us about learning. Nat. Insight Rev. 417, 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doupe AJ, Kuhl PK. 1999. Birdsong and human speech: common themes and mechanisms. Annu.Rev.Neurosci. 22, 567–631. ( 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.567) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfenning AR. et al. 2014. Convergent transcriptional specializations in the brains of humans and song-learning birds. Science 346, 1256846 ( 10.1126/science.1256846) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarvis ED. 2004. Learned birdsong and the neurobiology of human language. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1016, 749–777. ( 10.1196/annals.1298.038) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bottjer SW, Arnold AP. 1997. Developmental plasticity in neural circuits for a learned behavior. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 459–481. ( 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.459) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bottjer SW, Johnson F. 1992. Matters of life and death in the songbird forebrain. J. Neurobiol. 23, 1172–1191. ( 10.1002/neu.480230909) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nixdorf-Bergweiler BE. 1996. Divergent and parallel development in volume sizes of telencephalic song nuclei in male and female zebra finches. J. Comp. Neurol. 375, 445–456. ( 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961118)375:3%3C445::AID-CNE7%3E3.0.CO;2-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bottjer SW, Glaesner SL, Arnold AP. 1985. Ontogeny of brain nuclei controlling song learning and behavior in zebra finches. J. Neurosci. 5, 1556–1562. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-06-01556.1985) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller-Sims VC, Bottjer SW. 2012. Auditory experience refines cortico-basal ganglia inputs to motor cortex via remapping of single axons during vocal learning in zebra finches. J. Neurophysiol. 107, 1142–1156. ( 10.1152/jn.00614.2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balmer TS, Carels VM, Frisch JL, Nick TA. 2009. Modulation of perineuronal nets and parvalbumin with developmental song learning. J. Neurosci. 29, 12 878–12 885. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2974-09.2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer CA, Boroda E, Nick TA. 2014. Sexually dimorphic perineuronal net expression in the songbird. Basal Ganglia 3, 229–237. ( 10.1016/j.baga.2013.10.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cornez G, Ter Haar SM, Cornil CA, Balthazart J. 2015. Anatomically discrete sex differences in neuroplasticity in zebra finches as reflected by perineuronal nets. PLoS ONE 10, e0123199 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0123199) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cornez G, Madison FN, Van Der Linden A, Cornil C, Yoder KM, Ball GF, Balthazart J. 2017. Perineuronal nets and vocal plasticity in songbirds: a proposed mechanism to explain the difference between closed-ended and open-ended learning. Dev. Neurobiol. 77, 975–994. ( 10.1002/dneu.22485) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vates GE, Broome BM, Mello CV, Nottebohm F. 1996. Auditory pathways of caudal telencephalon and their relation to the song system of adult male zebra finches (Taenopygia guttata). J. Comp. Neurol. 366, 613–642. ( 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960318)366:4%3C613::AID-CNE5%3E3.0.CO;2-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woolley SMN. 2012. Early experience shapes vocal neural coding and perception in songbirds. Dev. Psychobiol. 54, 612–631. ( 10.1002/dev.21014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Ruijssevelt L, Chen Y, Von Eugen K, Hamaide J, De Groof G, Verhoye M, GüntürküN O, Woolley SC, Van Der Linden A. 2018. fMRI Reveals a novel region for evaluating acoustic information for mate choice in a female songbird. Curr. Biol 28, 711–721. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.048) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karten HJ, Brzozowska-Prechtl A, Lovell PV, Tang DD, Mello CV, Wang H, Mitra PP. 2013. Digital atlas of the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) brain: a high-resolution photo atlas. J. Comp. Neurol. 521, 3702–3715. ( 10.1002/cne.23443) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinaud R, Mello CV. 2007. GABA immunoreactivity in auditory and song control brain areas of zebra finches. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 34, 1–21. ( 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2007.03.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu H, Gan J, Jonas P. 2014. Interneurons. Fast-spiking, parvalbumin+ GABAergic interneurons: from cellular design to microcircuit function. Science 345, 1255263 ( 10.1126/science.1255263) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris NP, Henderson Z. 2000. Perineuronal nets ensheath fast spiking, parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in the medial septum/diagonal band complex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 828–838. ( 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00970.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liberti WA, et al. 2016. Unstable neurons underlie a stable learned behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1665–1671. ( 10.1038/nn.4405) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wintergerst ES, Faissner A, Celio MR. 1996. The proteoglycan DSD-1-PG occurs in perineuronal nets around parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneurons of the rat cerebral cortex. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 14, 249–255. ( 10.1016/0736-5748(96)00011-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaughnessy DW, Flores D, Moore L, Bertram R, Wu W, Hyson RL, Johnson F. 2016. Brain connectivity not to blame for a sex difference in singing behavior of zebra finches. Abstract 629.04/AAA23 San Diego, CA: Society for Neuroscience. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brainard MS. 2004. Contributions of the anterior forebrain pathway to vocal plasticity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1016, 377–394. ( 10.1196/annals.1298.042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bottjer SW, Miesner EA, Arnold AP. 1984. Forebrain lesions disrupt development but not maintenance of song in passerine birds. Science 224, 901–903. ( 10.1126/science.6719123) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boettiger CA, Doupe AJ. 1998. Intrinsic and thalamic excitatory inputs onto songbird LMAN neurons differ in their pharmacological and temporal properties. J. Neurophysiol. 79, 2615–2628. ( 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2615) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin Wild J, Williams MN, Suthers RA. 2001. Parvalbumin-positive projection neurons characterise the vocal premotor pathway in male, but not female, zebra finches. Brain Res. 917, 235–252. ( 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02938-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gobes SMH, Bolhuis JJ. 2007. Birdsong memory: a neural dissociation between song recognition and production. Curr. Biol. 17, 789–793. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.059) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grace JA, Amin N, Singh NC, Theunissen FE. 2003. Selectivity for conspecific song in the zebra finch auditory forebrain. J. Neurophysiol. 89, 472–487. ( 10.1152/jn.00088.2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mello CV, Clayton DF. 1994. Song-induced ZENK gene expression in auditory pathways of songbird brain and its relation to the song control system. J. Neurosci. 14, 6652–6666. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06652.1994) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mello CV, Vicario DS, Clayton DF. 1992. Song presentation induces gene expression in the songbird forebrain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 6818–6822. ( 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6818) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stripling R, Kruse AA, Clayton DF. 2001. Development of song responses in the zebra finch caudomedial neostriatum: role of genomic and electrophysiological activities. J. Neurobiol. 48, 163–180. ( 10.1002/neu.1049) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mello C, Nottebohm F, Clayton D. 1995. Repeated exposure to one song leads to a rapid and persistent decline in an immediate early gene's response to that song in zebra pinch telencephalon. J. Neurosci. 15, 6919–6925. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06919.1995) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chew SJ, Mello C, Nottebohm F, Jarvis ED, Vicario DS. 1995. Decrements in auditory responses to a repeated conspecific song are long-lasting and require two periods of protein synthesis in the songbird forebrain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 3406–3410. ( 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3406) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gentner TQ, Margoliash D. 2003. Neuronal populations and single cells representing learned auditory objects. Nature 424, 669–674. ( 10.1038/nature01731) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson JV, Gentner TQ. 2010. Song recognition learning and stimulus-specific weakening of neural responses in the avian auditory forebrain. J. Neurophysiol. 103, 1785–1797. ( 10.1152/jn.00885.2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Best BJ, Day NF, Larson GT, Carels VM, Nick TA. 2011. Vocal effects of perineuronal net destruction in adult zebra finch. 303.18/XX51 Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cornez G, Jonckers E, ter Haar SM, Van der Linden A, Cornil CA, Balthazart J. 2018. Data from: Timing of perineuronal net development in the zebra finch song control system correlates with developmental song learning Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.515n9k9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Cornez G, Jonckers E, ter Haar SM, Van der Linden A, Cornil CA, Balthazart J. 2018. Data from: Timing of perineuronal net development in the zebra finch song control system correlates with developmental song learning Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.515n9k9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data raw data are available for review at Dryad Digital Repository (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.515n9k9) [53].