Abstract

Background/Purpose:

Fatigue is a major concern for individuals with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). However, in order to treat fatigue adequately, its sources need to be identified.

Methods:

Data were collected during a single home visit (n=158). All participants had physician-diagnosed RA. Assessments were made of self-reported sleep quality, depression, physical activity, RA disease activity, muscle strength, functional limitations, and body composition. Information was collected on demographics, medications, and smoking. The Fatigue Severity Index (FSI; average fatigue over the past 7 days) was used as the primary outcome. Analyses were first conducted to evaluate bivariate relationships with fatigue. Correlations among risk factors were examined. Multivariate analyses identified independent predictors of fatigue.

Results:

Mean age (±SD) was 59 (±11), mean disease duration was 21 (±13) years, and 85% were female. Mean FSI rating was 3.8 (±2.0; range 0–10). In multivariate analyses, self-reported disease activity, poor sleep, depression, and obesity were independently associated with fatigue. Physical inactivity was correlated with poor sleep, depression, and obesity. Mediation analyses indicated that physical activity had an indirect association with fatigue, mediated by poor sleep, depression, and obesity.

Conclusion:

This cross-sectional study suggests that fatigue may not be solely a result of RA disease activity, but may result from a constellation of factors, including RA disease activity or pain, but also inactivity, depression, obesity, and poor sleep. Results suggest new avenues for interventions to improve fatigue in individuals with RA, such as increasing physical activity or addressing depression or obesity.

Fatigue is almost universally experienced by individuals with RA, is perceived to have a significant impact on health status, physical and social functioning, and health care utilization, and can make management of other RA symptoms more challenging[1]. The EULAR/ACR Collaborative Recommendations on reporting disease activity in clinical trials in RA include fatigue as a key outcome measure[2].

Although recognition of the importance of fatigue has grown, physicians report inadequate knowledge about the etiology of RA fatigue and evidence-based interventions to prevent and treat it[3]. Studies have examined factors associated with RA fatigue, with pain, disease activity, and depression most commonly noted as risk factors, as well as inflammation and sleep disturbance[1,4–9], yet few studies have included all of these factors. In non-rheumatic conditions, additional factors, such as physical inactivity, obesity, low fitness, and skeletal muscle weakness have been linked to fatigue[10,11], but these have not been examined simultaneously as predictors of fatigue in RA, even though they are commonly present in individuals with RA. For this study, we integrated findings from previous studies of fatigue in both RA and non-RA samples to explore a more comprehensive view of potential risk factors for RA fatigue than have been included in previous studies.

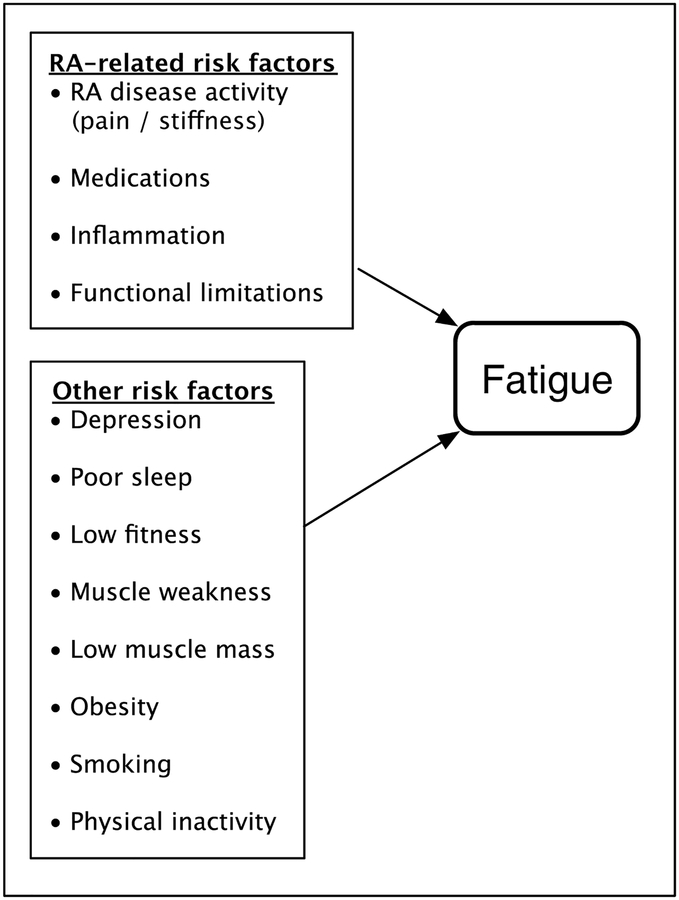

Risk factor selection

Both RA-specific and other risk factors were hypothesized to influence RA fatigue (Figure 1). Non-RA-specific factors were either identified from previous research or chosen based on the theoretical concept of mismatch between an individual’s capacity and the demands of the environment that was first introduced in discussions of disability[12]. For example, the energy required for tasks can be increased by pain, functional limitations, or structural abnormalities (RA-specific risk factors), but also by elevated fat mass[13]. Low aerobic capacity and muscle strength reduce functional capacity[13]. Combined, these factors mean that energy requirements for a given task may be greater, but that the individual’s capacity for performing the task is decreased. This mismatch between task demands and physical capabilities may force individuals to dip into functional reserves to a greater extent than might be expected, and may then lead to elevated levels of fatigue.

Figure 1.

Initial theoretical model of RA fatigue.

As a caveat to further discussion of potential risk factors for fatigue and the data analysis, we recognize that with cross-sectional analyses such as those performed here, directionality and causality are theoretical and cannot be demonstrated.

RA-specific risk factors.

Self-reported RA disease activity, functional limitations, RA medications, and inflammation were examined as RA-specfiic risk factors for fatigue. Pain and RA disease activity have been directly related to fatigue in a number of studies[5,7]. Pain can also increase energy required for tasks[14]. Fatigue is greater among individuals with greater functional limitations[5]. Joint deformities, swelling, or functional impairments may decrease the efficiency of movement, requiring more energy or use of less developed muscles to avoid pain[14]. RA medications, particularly glucocorticoids and biologics, may affect fatigue[15–17]. Inflammatory markers that may be elevated in RA have been linked to fatigue and to possible non-RA-specific risk factors for fatigue such as sleep disturbance and muscle weakness[18,19].

Other risk factors.

Sleep disturbance, depression, body composition (obesity, low lean mass), muscle strength, cardiovascular fitness, physical inactivity, smoking, and demographic characeristics were examined as non-RA-specific risk factors of fatigue. Prior studies in RA have demonstrated that sleep disturbances may play a role in RA fatigue [6,7]. Pain is also a well-recognized cause of sleep disturbance among individuals with RA[18]. Depression is strong predictor of fatigue in the general older population and in RA[4,7,10]. Depression can also affect sleep[18].

While some studies have found that body composition (i.e., high body mass index [BMI], low lean mass, and/or high fat mass) is an independent predictor of fatigue[10], body composition may also influence fatigue through indirect means. For example, chronic inflammation seen in RA can affect body composition and metabolism resulting in rheumatoid cachexia, or the loss of lean body mass, particularly skeletal muscle[19,20], which in turn can reduce muscle strength and increase the functional burden of daily tasks [21]. Obesity is also linked to sleep disorders[22].

Greater self-reported physical activity has been directly linked to lower levels of fatigue [23], and exercise training appears to improve fatigue levels and sleep[21,24,25]. Exercise may also mitigate effects of sarcopenia and rheumatoid cachexia[19]. Low levels of usual physical activity could increase risk of high body fat mass, low muscle mass, elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, and/or reduced cardiovascular fitness[19], any of which could influence fatigue levels. Studies among individuals with RA have typically found low levels of usual physical activity[26,27], and decreased aerobic capacity[27].

Smoking has been linked to fatigue in RA[28]. Fatigue has been found to be more common in women and older individuals[21,28]. Racial and ethnic differences in RA symptoms have been also observed[29].

Methods

Subjects and data collection

Subjects (n=158) were recruited from an ongoing longitudinal cohort study of individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, the UCSF RA Panel (n=65)[30]; from a previous in-person clinical study, the Arthritis Body Composition and Disability study (n=13)[31]; and from academic (n=73) and community rheumatology clinics (n=7). All had physician-documented rheumatoid arthritis. Data were collected in a single in-person visit performed by trained research assistants. The study was approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research, and all subjects provided written consent to participate.

Variables

Fatigue

Fatigue was measured with the Fatigue Severity Index (FSI), which has excellent validity and reliability and has been used in a variety of chronic disease cohorts[32,33]. The FSI consists of 11 items, each rated on a 0–10 scale. Single items ask respondents to rate the average level of fatigue severity over the past week, as well the level of fatigue on the days with the most and least fatigue, the number of days with fatigue, during how much of the day fatigue was experienced, and the current level of fatigue; each of these items can be considered separately for analysis. A fatigue interference scale can be calculated from the remaining items. We used the average level of fatigue severity over the past week as the primary measure of fatigue. Analyses were repeated with the other FSI individual items and the interference scale.

Risk factors for fatigue

RA-specific risk factors

RA disease activity was measured with the Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index (RADAI), which includes self-report of global disease activity, pain, joint tenderness and swelling, and duration of morning stiffness[34]. Scores range from 0–10, with higher scores indicating greater disease activity. Because ratings of pain have been used in previous studies of RA fatigue, we examined the pain component of the RADAI alone; in regression models, the RADAI composite score demonstrated stronger associations with fatigue than pain alone, so we retained the composite score.

Self-reported functional limitations were assessed with the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)[35]. HAQ scores range from 0–3, with higher scores reflecting greater limitations. Glucocorticoid use and dosage and use of biologic therapy were obtained by self-report. Blood was drawn, and high-density C-reactive protein (CRP) analyzed by a commercial laboratory. CRP values were highly skewed and were log-transformed for analysis. Duration of RA has not been specifically tied to fatigue, but was obtained from self-report and examined as a potential risk factor.

Non-RA-specific risk factors

Self-reported sleep quality was measured with the overall sleep quality score of the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)[36]. This score theoretically ranges from 0–21, with higher scores representing worse sleep quality. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which was designed to correspond to the diagnostic criteria for depressive disorders[37]. Scores range from 0–27; a score of 10 or above is considered to indicate major depressive disorder.

Body composition (i.e., high body mass index [BMI], low lean mass, and/or high fat mass) was estimated by bioelectrical impedance (BIA; Quantum II Bioelectrical Body Composition Analyzer, RLJ Systems, Clinton Township, Michigan, USA) and by BMI calculated from measured height and weight. Estimates of lean and fat mass were determined from BIA using the sex-specific equations from NHANES III[38]. The ratio of lean-to-fat mass was used in regression analyses to account for the collinearity between lean and fat mass[39]. RA-specific BMI cut-points were used to define obesity: ≥26.1 for women and ≥24.7 for men[31]. The traditional obesity cut-point (BMI≥30) was also examined.

Knee extension and hip flexion isometric strength were measured by hand-held dynamometer (MicroFet2 dynamometer, Saemmons Preston, Bolingbrook, Ill, USA) following standard manual muscle testing procedures[40]. Examiners were trained in muscle testing by an experienced physical therapist. Research assistants completed training with control subjects until there was agreement between raters 90% of the time within 5 pounds of force. Three trials were performed of each muscle group in alternating fashion and the maximum selected for analysis.

We measured usual levels of physical activity by self-report with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)[41]. The IPAQ queries physical activity across 4 domains during the previous week: leisure, domestic and yard activities, work, and transportation. Within each domain, the number of minutes of moderate or vigorous activity (MVA) is collected. The total number of minutes in MVA was calculated, and individuals were categorized as inactive (<150 minutes/week) or active (≥150 minutes/week), based on physical activity guidelines published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/guidelines/adults.html). Resting heart rate was used as a proxy for cardiorespiratory fitness[42], and was measured by pulse oximeter after a minimum of 15 minutes of sitting quietly while completing questionnaires.

Sex, age, race/ethnicity, smoking history, and current smoking were obtained by self-report.

Data analysis

Descriptive means and frequency distributions were calculated. Relationships among all potential risk factors were examined. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated due to non-normal distributions of some variables. Bivariate associations of all potential risk factors with fatigue severity (FSI Average Severity) were calculated. Multivariate linear regression analyses were conducted that included all predictors significantly (p≤0.05) associated with fatigue in bivariate analyses. Regression models were initially constructed separately for RA-specific risk factors and non-RA-specific risk factors. Next, significant predictors from the RA-specific and non-RA-specific analyses were combined into a single regression analysis. Subsequent models deleted variables that did not appear to contribute to the overall predictive ability of the model, and differences in the predictive ability of modified models were tested using restricted F-tests. Tests of multicollinearity were conducted. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were repeated using other FSI individual items and the fatigue interference scale, as described above, as sensitivity analyses. Results were not substantively different and are not presented. To test for indirect effects of explanatory variables, tests of mediation were conducted using the method described by Baron and Kenny[43].

Results

Sample characteristics

Participants were 84.8% female, and 74.7% white, non-Hispanic. Mean age was 59.2 (±11.3) years, and mean disease duration was 21.0 (±13.0) years. Mean RADAI score was 2.7, indicative of moderate disease activity[44]. About half were using oral glucocorticoids, and about half were using biologic therapies. Functional limitations were moderate, based on HAQ scores. Mean values of both hip extension and knee flexion strength were below age- and sex-based population norms[45].

Mean resting heart rate was 65.4 (±10.0), within the population average range[46]. While almost half had a history of smoking, fewer than 10% were current smokers. Approximately half of the sample reported moderate sleep quality and approximately one quarter reported poor sleep quality. Slightly over 40% had at least moderate levels of depressive symptoms, and over half were physically inactive. Over fifty percent were obese using RA-specific BMI cut-points. Mean FSI score was 3.8 (standard deviation 2.0) and scores ranged from 0–10

Correlations among non-RA-specific risk factors

All RA-specific variables were significantly inter-correlated (r’s ranging from 0.16 to 0.59). RADAI and HAQ scores were also significantly associated with almost all of the non-RA-specific variables, with correlations ranging from low to moderate. Physical inactivity was significantly associated with all other non-RA-specific variables.

Bivariate associations with fatigue

None of the demographic characteristics examined (age, sex, race) was significantly associated with fatigue (Table 3). Among the RA-specific variables, greater disease activity (higher RADAI scores), higher dosages of oral prednisone, greater systemic inflammation (CRP), and functional limitations (HAQ) were also associated with higher fatigue ratings.

Table 3.

Bivariate and multivariate associations with fatigue. Separate multivariate analyses for RA-specific and other risk factors

| Bivariate | Multivariate | Bivariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (p) | β (p) | β (p) | β (p) | |||

| Demographic | ||||||

| Age | −0.01 (.37) | --- | ||||

| Female | 0.14 (.75) | --- | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | −0.46 (.21) | --- | ||||

| RA-specific risk factors | Other risk factors* | |||||

| Duration of RA | −0.01 (.58) | --- | PSQI total score | 0.27 (<.0001) | 0.15 (.0006) | |

| RA Disease Activity Index (RADAI) | 0.65 (<.0001) | 0.52 (<.0001) | PHQ score | 0.24 (<.0001) | 0.12 (.001) | |

| Glucocorticoid use | 0.17 (.59) | --- | Physical inactivity† | 1.17 (.0002) | 0.31 (.26) | |

| Prednisone dose, mg | 0.09 (.07) | −0.03 (.57) | Obesity § | 1.29 (<.0001) | 0.77 (.01) | |

| Biologic use | −0.26 (.43) | --- | Lean mass / fat mass | −0.49 (.0009) | −0.12 (.38) | |

| C-reactive protein (log value) | 1.09 (.004) | 0.12 (.74) | Hip flexion strength | −0.56 (.005) | −0.07 (.72) | |

| Functional limitations, HAQ | 1.35 (<.0001) | 0.54 (0.04) | Knee extension strength | −0.07 (.40) | --- | |

| Resting heart rate | 0.03 (.05) | --- | ||||

| Smoking, ever | 0.95(.003) | --- | ||||

| Smoking, now | 2.31 (<.0001) | 0.98 (.06) | ||||

| Model F value (df) | 16.43 (4) | Model F value (df) | 16.96 (7) | |||

| Model R2 | 0.35 | Model R2 | 0.50 | |||

| Model adjusted R2 | 0.33 | Model adjusted R2 | 0.47 |

In the initial multivariate model, resting heart rate exhibited multicollinearity and was removed

Defined as <150 minutes of moderate or vigorous activity in responses to International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)

Women: BMI ≥ 26.1; men BMI ≥ 24.7 [31]

All of the non-RA specific risk factors – higher resting heart rate (as a proxy for low fitness), poor sleep quality, depression, physical inactivity, obesity, muscle weakness (in the hip, but not the knee), low lean-to-fat-mass ratio, and smoking – were significantly associated with fatigue in the bivariate analyses. While both current and ever smoking were significant, we chose to keep current smoking in the multivariate analysis because it was thought to be more relevant to current fatigue.

Multivariate analyses

RA-specific risk factors

The multivariate model for RA-specific risk factors included the four variables that were associated with FSI at p≤0.05 in the bivariate analyses: RADAI score, prednisone dose, CRP, and HAQ (Table 3). RADAI and HAQ scores were independently associated with FSI in the multivariate analysis. The adjusted R2 of the model was 0.33.

Non-RA-specific risk factors

The multivariate model for non-RA-specific risk factors included the eight variables that were associated with FSI at p≤0.05 in bivariate analyses: PSQI sleep quality score, PHQ depressive symptom score, physical inactivity, obesity, lean-to-fat-mass ratio, hip flexor strength, resting heart rate, and current smoking (Table 3). Resting heart rate exhibited multicollinearity and was removed from the model. PSQI, PHQ, obesity, and current smoking emerged as significant independent predictors of FSI. The adjusted R2 of the model was 0.47.

Combined model.

The first combined model included variables with p≤.40 in the two multivariate analyses above, and yielded an adjusted R2 of 0.48. Model 2 deleted variables with p>0.40 (HAQ and lean mass), yielding an adjusted R2 of 0.49. Statistical comparison of the two models revealed that deletion of the two variables did not significantly change the predictive power of the regression model. One additional variable (physical inactivity, p=0.28) was dropped to create Model 3. The R2 for Model 3 was 0.49, and the overall predictive power of Model 3 was not significantly different from Model 1. In the final model, greater disease activity, poor sleep, higher levels of depressive symptoms, and obesity were independent predictors of fatigue.

Mediation analysis

Physical inactivity was significantly associated with fatigue in the bivariate analysis and significantly correlated with each of the non-RA-specific risk factors that remained in Model 3, yet not statistically significant in the multivariate model. Because of this, we tested whether its effects were indirect, i.e., mediated by other variables in the regression model. Sobel tests of mediation showed that PSQI score, PHQ score, and obesity each mediated the effects of inactivity on fatigue (all p<.05)[47].

Discussion

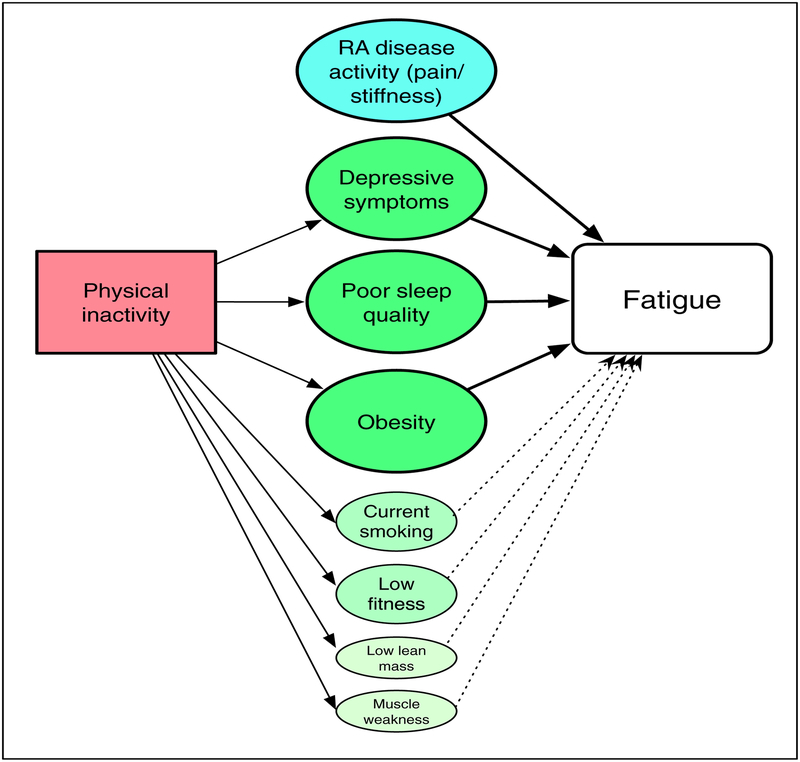

The results of these analyses suggest a more complex picture of RA fatigue than has been examined previously. Our results showed that in addition to disease activity, the primary predictors of fatigue are poor sleep, depression, and obesity (Figure 2). Smoking, muscle weakness, low lean mass, and low cardiovascular fitness were also significantly associated in bivariate analyses, but not in the multivariate analyses. Physical inactivity was significantly associated with each of these factors, and our results suggest that poor sleep, depression, and obesity mediate the direct influence of inactivity on fatigue. In our analyses, the model including only non-RA-specific risk factors actually accounted for a greater proportion of variance in fatigue than the model with only RA-specific factors, and including the RA-specific factors yielded an R2 only slightly greater than that of the non-RA-specific factors alone. This finding has important implications for development of new interventions for RA fatigue.

Figure 2.

Theoretical model of behavioral impact on RA fatigue based on study analyses.

Note: Solid lines from Physical Inactivity represent statistically significant correlations. Solid lines to Fatigue represent associations that were statistically significant in multivariate analyses; dotted lines represent associations that were statistically significant in bivariate analyses, but not multivariate.

The size of the circles represents the relative contribution of factors to fatigue.

Our findings support results reported by Nicassio and colleagues, who also found that depressed mood and poor sleep were independent predictors of fatigue in RA after controlling for disease activity[7]. That analysis, however, included only mood disturbance, sleep quality, disease activity, and medications. In the recent past, several other studies have attempted to identify predictors of fatigue severity in RA[5,8,9], and have found greater pain to be associated with fatigue severity. In addition to the Nicassio study, some of these other studies have included depression and/or sleep disturbance and found each to also be a significant predictor of RA fatigue[4,6].

While the roles of sleep disturbance and depression in RA fatigue have previously been demonstrated, the roles of other non-RA-specific risk factors have received little attention. For example, both cardiovascular fitness and muscle strength are likely to improve an individual’s physiological resources to respond to demands of the environment, but neither has been studied in RA. In the general population, obesity has consistently been linked to more severe fatigue[10]. The high prevalence of obesity in RA[31] adds to the importance of examining its role in RA fatigue. Likewise, physical inactivity, which is also highly prevalent in individuals with RA, has been linked to greater fatigue in the general population[11].

In spite of evidence from clinical trials of biologics that showed a positive impact of these therapies on fatigue, we did not find an association of biologics with fatigue. However, even in the trials noted above, the effect on fatigue did not appear to be independent of disease activity, and none of the previous observational studies that included treatment variables found significant independent effects of DMARD or biologic therapies on fatigue after controlling for pain or disease activity[4,5,7,48].

Hewlett and colleagues proposed a comprehensive conceptual model whereby disease factors, “cognitive and behavioral” factors (e.g., self-efficacy, depression), and “personal life issues” (e.g., social support, work, environment) interact to drive RA fatigue[49]. While our study did not include all of these factors, it is the most comprehensive examination of factors associated with RA fatigue to date. As noted above, our study was cross-sectional, so even though our theoretical model proposes causal relationships, we are able to report only associations, not longitudinal predictors of risk. An additional limitation due to the cross-sectional design is that we cannot observe reciprocal effects of fatigue on other factors. For example, greater levels of fatigue may lead to greater inactivity or higher levels of depressive symptoms. We examined a single dimension of fatigue – severity. It is possible that we may have found different correlates if we had focused on other dimensions or types of fatigue, such as the impact of fatigue or physical vs. cognitive fatigue. In addition, our measure was not RA-specific, but it is well-validated and has been used in a variety of health conditions. Additionally, there is no reason to think that the construct of fatigue severity is RA-specific; indeed, a numeric rating scale of fatigue severity has been used in many studies of RA fatigue.

The relationships we observed with fatigue may be sample-specific, and examination in other samples may yield different results. The study sample included only English-speaking participants, so additional or different factors may come into play for other language groups. Some of our measures of predictors had limitations. For example, sleep disturbance was self-reported, and could have been biased by depression, and the proxy assessment of cardiovascular fitness could be flawed because of the effects of beta-blockers or other medications. Important variables may have been excluded; for example, we did not include non-RA medications and we did not have information on chronic levels of pain, which have been shown to have strong associations with fatigue in other populations[50,51]. In spite of these limitations, though, our findings were consistent with other research.

This study included only individuals with RA, but high levels of fatigue have been found in other rheumatic conditions, including osteoarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis [52–57]. Relatively high prevalence rates of obesity, depression, sleep disturbance, and/or inactivity have been reported each of these conditions [58–63], so it is possible that these factors may play an important role in fatigue in other rheumatic conditions. In fibromyalgia, another condition with high levels of fatigue, sleep disturbances, depression, obesity, and inactivity are common[64,65]. In fact, physical activity or exercise interventions have been identified as effective interventions for fibromyalgia symptoms[66].

We examined the indirect effects of physical inactivity using mediation analysis, discovering an important role for inactivity that was not apparent in the primary multivariate analyses. Additional mediated effects may be present in the model we show in Figure 2. For example, the effects of inflammation may be mediated by self-reported disease activity. However, in order to present a more parsimonious model, we did not show additional mediated effects. Nonetheless, this finding highlights the importance of examining relationships among predictors and consideration of both direct and mediated effects of variables when trying to construct causal pathways or theoretical models.

This study presents novel additions to the study of factors potentially affecting fatigue in RA, specifically, obesity, muscle strength, and fitness, and examined the most comprehensive range of fatigue predictors to date. The relationships we observed potentially represent new avenues for the treatment of RA fatigue. A Cochrane review noted that both psychosocial and physical activity interventions had modest effects on RA fatigue[25], but the psychosocial and activity interventions reviewed were quite varied, so that recommendations for optimal management of RA fatigue still do not exist. In addition, all of those interventions required resources that are not likely to be widely available or have substantial barriers to uptake(e.g., trained instructors or group leaders, attendance at group sessions). Interventions focused on the more general behavioral factors identified in our study may be more easily disseminated.

Given the importance of the non-RA-specific risk factors found in our study, a question arises regarding the relative contribution of inflammatory RA disease activity to fatigue symptoms. Studies of fatigue in other populations have found risk factors similar to those that we found. For example, in studies of both the general adult population and older adults, fatigue has been linked to inflammation (CRP), pain, depression, low levels of physical activity, poor sleep quality, and obesity[10,11] – the same factors we found associated with fatigue in individuals with RA. While the prevalence, severity, and impact of fatigue may be greater in RA, our results would suggest that fatigue may not be solely a direct result of RA disease activity, but may instead be the result of a constellation of factors that include pain or RA disease activity, but also include depression, obesity, poor sleep, and physical inactivity, each of which may or may not have roots in RA or RA symptoms. Even so, fatigue is highly prevalent in RA, its impact on functioning and quality of life is great, and current treatments are limited both in availability and effectiveness. Our results provide a basis for future study, and, perhaps most importantly, suggest new avenues for interventions aimed at improving fatigue in individuals with RA, such as increasing physical activity or addressing obesity or depression.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n = 158)

| Mean ± SD | % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Age | 59.2 ± 11.3 | |

| Female | 84.8 (118) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 74.7 (118) | |

| RA-specific risk factors | ||

| Duration of RA | 21.1 ± 12.5 | |

| RA Disease Activity Index | 2.7 ± 1.7 | |

| Glucocorticoid use | 45.9 (72) | |

| Prednisone dose, mg | 5.1 ± 2.6 | |

| Biologic use | 50.6 (80) | |

| C-reactive protein (median [IQR], range) | 0.20 [0.1, 0.5], 0 – 20.9 | |

| Functional limitations, Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) | 0.90 ± 0.72 | |

| Other risk factors | W | |

| Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), total score | 8.4 ± 3.8 | |

| Good sleep (PSQI score 0 – 5) | 25.3 (40) | |

| Moderate sleep (PSQI score 6 – 10 | 47.5 (75) | |

| Poor sleep (PSQI score ≥ 11) | 27.2 (43) | |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) score | 4.7 ± 4.8 | |

| Moderate depression (PHQ 5 – 9) | 27.2 (43) | |

| Severe depression (PHQ ≥ 10) | 13.9 (22) | |

| Physical inactivity* | 52.5 (83) | |

| Obesity, Body mass index (BMI) † | 52.5 (83) | |

| Lean-to-fat mass ratio | 2.0 ± 1.1 | |

| Hip flexion strength, Kg | 10.9 ± 3.8 | |

| Knee extension strength, Kg | 26.4 ± 9.0 | |

| Resting heart rate | 65.4 ± 10.0 | |

| Smoking, ever | 46.8 (74) | |

| Smoking, now | 7.6 (12) |

Defined as <150 minutes of moderate or vigorous activity in responses to International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)

Women: BMI ≥ 26.1; men BMI ≥ 24.7 (reference)

Table 2.

Correlations among behavioral predictors of fatigue

| RA-specific risk factors | Other risk factors | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RADAI score | HAQ score | CRP (log) | Prednisone dose | Current smoking | Muscle weakness | Lean/fat ratio | Fitness | Sleep quality | Depressive symptoms | Obesity | |

| RADAI score | --- | ||||||||||

| HAQ score | 0.59**** | --- | |||||||||

| CRP (log) | 0.40**** | 0.39**** | --- | ||||||||

| Prednisone dose | 0.27 *** | 0.16* | 0.33**** | --- | |||||||

| Current smoking | 0.34**** | 0.14 | 0.20* | 0.17* | --- | ||||||

| Muscle weakness (hip strength) | −0.27*** | −0.37**** | −0.09 | −0.10 | 0.01 | --- | |||||

| Lean/fat mass ratio | −0.17* | −0.31**** | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.35**** | --- | ||||

| Fitness (resting heart rate) | 0.11 | 0.18* | 0.37**** | 0.31**** | 0.20* | −0.14 | −0.04 | --- | |||

| Sleep quality (PSQI score) | 0.49**** | 0.549*** | 0.21* | 0.19* | 0.26*** | −0.21** | −0.14 | 0.15 | --- | ||

| Depressive symptoms (PHQ score) | 0.55**** | 0.41**** | 0.28*** | 0.18* | 0.42**** | −0.14 | −0.10 | 0.17* | 0.55**** | --- | |

| Obesity | 0.21** | 0.33**** | 0.20* | −0.02 | 0.13 | 0.03 | −0.46**** | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.21* | --- |

| Physical inactivity | 0.23** | 0.28*** | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.22** | −0.22* | −0.22** | 0.23** | 0.18* | 0.24*** | 0.29**** |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001,

p<.0001

Table 4.

Multivariate associations with fatigue, including both RA-specific and non-RA-specific risk factors

| Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| β (p) | β (p) | β (p) | |

| RA-specific risk factors | |||

| RA Disease Activity Index (RADAI) | 0.21 (.06) | 0.23 (.01) | 0.25 (.009) |

| Functional limitations, HAQ | 0.11 (0.65) | --- | --- |

| Other risk factors | |||

| PSQI total score | 0.12 (.01) | 0.15 (.0003) | 0.13 (.004) |

| PHQ score | 0.10 (.009) | 0.08 (.02) | 0.10 (.01) |

| Physical inactivity* | 0.28 (.32) | 0.27 (.28) | --- |

| Obesity † | 0.65 (.04) | 0.83 (.001) | 0.85 (.001) |

| Lean mass / fat mass | −0.11 (.43) | --- | --- |

| Smoking, now | 0.81 (.12) | 0.71 (.15) | 0.80 (.12) |

| Model F value (df) | 16.07 (8) | 21.30 (6) | 25.19 (5) |

| Model R2 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

| Model adjusted R2 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 |

| F-test for difference in model compared to Model 1, F (p) | 0.70 (.50) | 1.42 (0.24) | |

Defined as <150 minutes of moderate or vigorous activity in responses to International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)

Women: BMI ≥ 26.1; men BMI ≥ 24.7 [31]

Model 1: In the initial multivariate model, all variables with p<0.40 in separate RA-specific and non-RA-specific multivariate models were included.

Model 2: Variables with p>0.40 were deleted (HAQ, lean mass)

Model 3: Inactivity deleted

Significance and Innovation.

Previous studies of RA fatigue have examined the role of poor sleep and depression or mood disturbance, but none have examined non-RA-specific modifiable risk factors that have been shown in other contexts to make significant contributions to fatigue, such as obesity, physical inactivity, or low cardiorespiraotry fitness.

Findings suggest that, after accounting for factors traditionally considered part of the disease process itself, such as inflammation and self-reported disease activity (which includes joint pain and swelling), much of RA fatigue is associated with obesity, poor sleep quality, and depression, which are commonly present in RA.

Physical inactivity also appears to play a role in RA fatigue, with its effects mediated by obesity, poor sleep quality, and depression.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Rheumatology Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Nikolaus S, Bode C, Taal E, et al. Fatigue and factors related to fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65:1128–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, et al. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(10):1371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Repping-Wuts H, van Riel P, van Achterberg T. Rheumatologists’ knowledge, attitude and current management of fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Clin Rheumatol. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stebbings S, Herbison P, Doyle T, et al. A comparison of fatigue correlates in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: disparity in associations with disability, anxiety, and sleep disturbance. Rheumatology. 2010;49:361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell R, Batley M, Hammond A, et al. The impact of disease activity, pain, disability, and treatments on fatigue in established rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:717–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwin M, Olmstead R, Carrillo C, et al. Sleep loss exacerbates fatigue, depression, and pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Sleep. 2012;35:537–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicassio P, Ormseth S, Custodio M, et al. A multidimensional model of fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1807–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Dartel S, Repping-Wuts J, van Hoogmoed D, et al. Association between fatigue and pain in rheumatoid arthritis: does pain precede fatigue or does fatigue precede pain? Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65:862–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rongen-van Dartel S, Repping-Wuts J, van Hoogmoed D, et al. Relationship between objectively assessed physical activity and fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: inverse correlation of activity and fatigue. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:852–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim W, Hong S, Nelesen R, et al. The association of obesity, cytokine levels, and depressive symptoms with diverse measures of fatigue in healthy subjects. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(8):910–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Resnick H, Carter E, Aloia M, et al. Cross-sectional relationship of reported fatigue to obesity, diet, and physical activity: reslts from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:163–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verbrugge L, Jette A. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brondel L, Mourey F, Mischis-Troussard C, et al. Energy cost and cardiorespiratory adaptation in the “get-up-and-go” test in frail elderly women with postural abnormalities and in controls. J Gerontol A BIol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60A:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belza B, Dewing K. Fatigue In: Bartlett S, editor. Clinical care in the rheumatic diseases. 3rd ed. Atlanta, GA: Association of Rheumatology Health Professions; 2006. p. 285–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yount S, Sorensen M, Cella D, et al. Adalimumab plus methotrexate or standard therapy is mroe effective than methotrexate or standard therapies alone in the treatment of fatigue in patients with active, inadequately treated rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:838–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreland L, Genovese M, Sato R, et al. Effect of etanercept on fatigue in patients with recent or established rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum (Arthritis Care Res). 2006;55:287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westhovens R, Cole J, Li T, et al. Improved health-related quality of life for rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with abatacept who have inadequate response to anti-TNF therapy in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomized clinical trial. Rheumatology. 2006;45:1238–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abad VC, Sarinas PS, Guilleminault C. Sleep and rheumatologic disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12(3):211–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsmith J, Roubenoff R. Cachexia in rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Cardiol. 2002;85:89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engvall IL, Elkan AC, Tengstrand B, et al. Cachexia in rheumatoid arthritis is associated with inflammatory activity, physical disability, and low bioavailable insulin-like growth factor. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008;37(5):321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans WJ, Lambert CP. Physiological basis of fatigue. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(1 Suppl):S29–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crummy F, Piper A, MT N. Obesity and the lung: 2. Obesity and sleep-disordered breathing. Thorax. 2008;63:738–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldman S, Ancoli-Israel S, Boudreau R, et al. Sleep problems and associated daytime fatigue in community-dwelling older individuals. J Gerontol A BIol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:1069–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durcan L, Wilson F, Cunnane G. The effect of exercise on sleep and fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled study. J Rheumatol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cramp F, Hewlett S, Almeida C, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for RA fatigue. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sokka T, Häkkinen A, Kautiainen H, et al. Physical inactivity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: data from twent-one countries in a cross-sectional, international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munsterman T, Takken T, Wittink H. Are persons with rheumatoid arthritis deconditioned? A review of physical activity and aerobic capacity. BMC Musculokelet Disord. 2012;13:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rat A, Pouchot J, Foutrel B, et al. Factors associated with fatigue in early arthritis: results from a multicenter national French cohort study. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1061–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barton J, Trupin L,D, Gansky S, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in disease activity and function among persons with rheumatoid arthritis from university-affiliated clinics. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:1238–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yelin E, Criswell L, Feigenbaum P. Health care utilization and outcomes among persons with rheumatoid arthritis in fee-for-service and prepaid group practice settings. JAMA. 1996;276:931–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz P, Yazdany J, Trupin L, et al. Sex differences in assessment of obesity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research. 2013;65:62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hann DM, Jacobsen PB, Azzarello LM, et al. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: development and validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(4):301–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitehead L The measurement of fatigue in chronic illness: a systematic review of unidimensional and multidimensional fatigue measures. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:107–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fransen J, Langenegger T, Michel B, et al. Feasibility and validity of the RADAI, a self-administered rheumatoid arthritis disease activity index. Rheumatology. 2000;39:321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fries J, Spitz P, Kraines R, et al. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:137–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omachi T Measures of sleep in rheumatologic diseases. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63 (Suppl):S287–S96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chumlea W, Guo S, Kuczmarski R, et al. Body composition estimates from NHANES III bioelectrical impedance data. Int J Obes. 2002;26:1596–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sternfeld B, Ngo L, Satariano W, et al. Associations of body composition with physical performance and self-reported functional limitation in elderly men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:110–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kendall F, McReary E, Provance P. Muscles, testing and function. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Craig C, Marshall A, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper K, Pollock M, Martin R, et al. Physical fitness levels vs selected coronary risk factors: a cross-sectional study. JAMA. 1976;236:166–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator varible distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fransen J, Hauselmann H, Michel B, et al. Responsiveness of the self-assessed Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index to a flare of disease activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bohannon R Reference values for extremity muscle strength obtained by hand-held dynamometry from adults aged 20 to 79 years. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Heart Association. Target heart rates [August 20, 2014]. Available from: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/PhysicalActivity/Target-Heart-Rates_UCM_434341_Article.jsp.

- 47.Sobel M Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. p. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chauffier K, Salliot C, Berenbaum F, et al. Effect of biotherapies on fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2012;51:60–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hewlett S, Chalder T, Choy E, et al. Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: time for a conceptual model. Rheumatology. 2011;50:1004–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters M, Sorbi M, Kruise D, et al. Electronic diary assessment of pain, disability and psychological adaptation in patients differing in duration of pain. Pain. 2000;84:181–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Avlund K Fatigue in older adults: an early indicator of the aging process? Aging Clin Exp Res. 2010;22:100–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolfe F, Hawley D, Wilson K. The prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1407–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bergman M, Shahouri S, Shaver T, et al. Is fatigue an inflammatory variable in rheumatoid arthritis (RA)? Analyses of fatigue in RA, osteoarthritis, and fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2788–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murphy S, ALexander N, Levoska M, et al. The relatinoship between fatigue and subsequent physical activity among older adults with symptomatic osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65:1617–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sterling K, Gallop K, Swinburn P, et al. Patient-reported fatigue and its impact on patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2014;23:124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walsh J, McFadden M, Morgan M, et al. Work productivity loss and fatigue in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1670–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brophy S, Davies H, Dennis M, et al. Fatigue in ankylosing spondylitis: treatment should focus on pain management. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;42:361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sturner T, Gunther K, Brenner H. Obesity, overweight and patterns of osteoarthritis: the Ulm Osteoarthritis Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:307–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palagini L, Mosca M, Tani C, et al. Depression and systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Lupus. 2013;22:409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palagini L, Tani C, Mauri M, et al. Sleep disorders and systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2014;23:115–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khraishi M, Aslanov R, TRampakakis E, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:1495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gezer O, Batmaz I, Sariyildiz M, et al. Sleep quality in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swinnen T, Scheers T, Lefevre J, et al. Physical activity assessment in patients with axial spondyloarthritis compared to healthy controls: a technology-based approach. Plos One. 2014;9:e85309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clauw D Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:1547–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim C, Luedtke C, Vincent A, et al. Association of body mass index with symptoms severity and quality of life in patients with fibromylagia. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:222–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaleth A, Slaven J, Ang D. Does increasing steps per day predict improvement in physical function and pain interference in adults with fibromyalgia? Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:1887–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]