Abstract

Communications across chemical synapses are primarily mediated by neurotransmitters and their postsynaptic receptors. There are diverse molecular systems to localize and regulate the receptors at the synapse. Here, we identify HPO-30, a member of the claudin superfamily of membrane proteins, as a positive regulator for synaptic localization of levamisole-dependent AChRs (LAChRs) at the Caenorhabditis elegans neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The HPO-30 protein localizes at the NMJ and shows genetic and physical association with the LAChR subunits LEV-8, UNC-29, and UNC-38. Using genetic and electrophysiological assays in the hermaphrodite C. elegans, we demonstrate that HPO-30 functions through Neuroligin at the NMJ to maintain postsynaptic LAChR levels at the synapse. Together, this work suggests a novel function for a tight junction protein in maintaining normal receptor levels at the NMJ.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Claudins are a large superfamily of membrane proteins. Their role in maintaining the functional integrity of tight junctions has been widely explored. Our experiments suggest a critical role for the claudin-like protein, HPO-30, in maintaining synaptic levamisole-dependent AChR (LAChR) levels. LAChRs contribute to <20% of the acetylcholine-mediated conductance in adult Caenorhabditis elegans; however, they play a significant functional role in worm locomotion. This study provides a new perspective in the study of LAChR physiology.

Keywords: AChRs, HPO-30, levamisole, neuromuscular junction

Introduction

Claudins are tetraspanin membrane proteins that play crucial roles in the formation and integrity of tight junctions and in regulating paracellular transport. Claudin proteins also function to regulate channel activity, intercellular signaling, and cell morphology (Turksen and Troy, 2004; Angelow et al., 2008). Expression of claudins in different organs and the deregulation of these proteins are associated with diseases, such as cancers, renal disorders, and deafness (Singh et al., 2010; Goncalves et al., 2013). In the nervous system, claudins serve as an integral component of the blood–brain barrier by regulating paracellular ion selectivity (Matter and Balda, 2003; Papadopoulos et al., 2004).

Most claudins have a PDZ binding motif at their C terminus that allows binding to the PDZ domains of cytoplasmic scaffold proteins, such as ZO-1/2/3, PATJ, and MUPP1. This association allows for claudins to form connections with the actin cytoskeleton (Itoh et al., 1999; Hamazaki et al., 2002; Sawada et al., 2003). Further, claudins are known to interact with nontight junction proteins, such as cell adhesion molecules EpCam, tetraspanin, and signaling proteins, such as ephrin A, ephrin B, and their receptors EphA and EphB (Ladwein et al., 2005; Tanaka et al., 2005a,b; Kovalenko et al., 2007; Rubinstein, 2011). The interaction of claudins with the actin cytoskeleton and with nontight junction proteins suggests that claudins might have functions other than in barrier formation. This work explores a nontight junction role for a Caenorhabditis elegans claudin-like protein, HPO-30.

The C. elegans genome encodes 18 claudins and claudin-like proteins ((Simske and Hardin, 2011) and wormbase (www.wormbase.org)). The functions of some of these claudin-like proteins have been studied. For example, CLC-1 localizes to epithelial cell junctions in the pharynx, where it regulates barrier functions (Asano et al., 2003). VAB-9, a divergent claudin-like protein, similar to vertebrate BCMP1 (brain cell membrane protein1), localizes to epithelial cell contacts and interacts with the cadherin-catenin complex during epidermal morphogenesis (Simske et al., 2003). Another protein, NSY-4, is related to the gamma subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels, TARP/Stargazin, as well as to other Claudin superfamily proteins. Previous studies have shown that the gamma subunit regulates the neuronal calcium channels and TARPs regulates AMPA-type glutamate receptor localization and activity (Heiskala et al., 2001; Arikkath and Campbell, 2003; Kang and Campbell, 2003; Van Itallie and Anderson, 2006). The C. elegans NSY-4 performs a dual function of regulating channel activity and adhesion function (Vanhoven et al., 2006). These functions of claudins in the regulation or recruitment of signaling proteins, cell adhesion molecules, and Ig proteins suggest important roles for claudins in the development and/or functioning of the nervous system.

To identify the function of the claudin family proteins at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction (NMJ), we performed an aldicarb-based screen on all available claudin mutants. We found mutants of a claudin homolog, hpo-30, to be extremely resistant to aldicarb. HPO-30 has previously been shown to be involved in the stabilization of dendritic branching of PVD neurons (Smith et al., 2013; O'Brien et al., 2017). Very recent studies show that HPO-30 functions through the WAVE regulatory complex and the membrane protein DMA-1 to allow for F-actin assembly and normal dendritic branching of the PVD neuron (Zou et al., 2018). Here we show that HPO-30 is required for the maintenance of levamisole sensitive AChRs (LAChRs) at the NMJ. Using genetic and electrophysiological analyses, we show that HPO-30 functions through Neuroligin/NLG-1 to maintain LAChRs at the NMJ. Together, our data implicate HPO-30 specifically in LAChR maintenance at the C. elegans NMJ.

Materials and Methods

Strains

All strains were maintained at 20°C as described previously (Brenner, 1974). The E. coli strain OP50 was used for seeding the C. elegans plates. The Bristol N2 strain was used as the wild-type (WT) control strain. The mutant strains used in this study were as follows: hpo-30 (ok2047), nlg-1 (ok259), nrx-1 (ok1649), and lev-8 (ok1519) (Jospin et al., 2009; Calahorro and Ruiz-Rubio, 2012, 2013; Hu et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2013). Further description of these alleles is available at wormbase (www.wormbase.org). All experiments in this study were performed using hermaphrodite C. elegans.

Constructs and transgenes

All constructs were generated using standard cloning procedures (Sambrook and Russell, 2001). pPD49.26 or pPD95.75 served as the vector backbone for all the constructs. The transcriptional reporter for hpo-30 was made by cloning a 3 kb region upstream of the hpo-30 start codon into the pPD95.75 vector. A 3 kb myo-3 promoter was used for expression of HPO-30 in the body-wall muscles, and a 1.4 kb rab-3 promoter was used for expression of HPO-30 pan-neuronally. For all the rescue experiments, a 1.5 kb genomic fragment of hpo-30 was cloned downstream of the various promoters. For the HPO-30 colocalization experiment, the mCherry was cloned downstream of HPO-30 in the Pmyo-3::HPO-30 plasmids. All the constructs were sequenced, and transgenic lines were generated by microinjection as described previously (Mello et al., 1991; Mello and Fire, 1995). A complete list of the primers used in this study is available in Table 1, and a complete list of the plasmids and strains used in this study is detailed in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Table 1.

List of primers

| Primer code | Sequence | Comment | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| PS104 | TTGGTGTGGCTCAGATTGTTC | Genotyping forward external | hpo-30 |

| PS105 | AGAGGACTAAACAACGAGAACGCAG | Genotyping forward internal | hpo-30 |

| PS106 | AATCTTGAGTGGCTCTGTTGG | Genotyping reverse external | hpo-30 |

| ST223 | CGCGGGATAGTGACGAAA | Genotyping forward external | nrx-1 |

| ST224 | CCATGCTCAACGAGAGAAGC | Genotyping forward internal | nrx-1 |

| ST225 | CCTCCGGCCATCAACTATC | Genotyping reverse external | nrx-1 |

| ST226 | GTGGATCCGTTCCGAAGA | Genotyping forward external | nlg-1 |

| ST227 | GAGAGCCCCTTATTCCACTG | Genotyping forward internal | nlg-1 |

| ST228 | GATGGACAGGTGGGTTGAAG | Genotyping reverse external | nlg-1 |

| PS344 | CATATGTATGTGTCTCTTGTTTCCG | Genotyping WT forward | lev-8 |

| PS345 | CATATGTATGTGTCTCTTGTTTCCA | Genotyping mutant forward | lev-8 |

| PS346 | TTGATCTGACGGAATGTGTA | Genotyping reverse | lev-8 |

| PS284 | AACTGCAGCAGCGTTGTGTTTCTGAAGATG | Cloning forward PstI | Phpo-30 |

| PS285 | CGGGATCCGTACATAATTAATGGCATTCCG | Cloning reverse BamH1 | Phpo-30 |

| PS402 | AATTAAGCTTAGTGATTATAGTCTCTGTTTTCGTTA | Cloning forward HindIII | Pmyo-3 |

| PS403 | ACTTGTCGACCATTTCTAGATGGATCTAGTG | Cloning reverse SalI | Pmyo-3 |

| PS453 | ACTTGTCGACTTATGTACAAATTTCTATTAGTCAC | Cloning forward SalI | HPO-30 |

| PS454 | AATTACCGGTCATACTGCTGTCATCGTCAAT | Cloning reverse SalI | HPO-30 |

| PS114 | ACTTAATGGCACGGATAGACAGAAGC | Cloning forward AflII | Prab-3 |

| PS115 | CCGCTCGAGTAACACTTCCTAGTAGTAATGCCTC | Cloning reverse Xho I | Prab-3 |

| PS130 | CCGCTCGAGATGCCATTAATTATGTACA | Cloning forward Xho I | hpo-30 |

| gDNA | |||

| PS136 | GGACTAGTTCACATACTGCTGTCATCGTC | Cloning reverse Spe I | hpo-30 |

| gDNA | |||

| PS434 | AACTAGCTAGCATCTTTCGGTCGTTGGTACG | Cloning forward NheI |

nlg-1 RNAi |

| PS435 | AAAACTGCAGCATTCACTTGGTTTGGGCTT | Cloning reverse PstI |

nlg-1 RNAi |

| PS436 | AAAAACTGCAGAACAAACGTCGTGTGCATGT | Cloning forward NheI |

hpo-30 RNAi |

| PS437 | AACTAGCTAGCTCCGTTCATTCCTCCAATTC | Cloning reverse PstI |

hpo-30 RNAi |

| PS304 | CGGAATTCCTACTTATACAATTCATCCATGCCACC | Cloning reverse EcoRI | mCherry |

| PS355 | AATTACCGGTATGGTCTCAAAGGGTGAAGAAG | Cloning forward Age I | mCherry |

| PS371 | TGTTGCTCATCAATGTGGACG | Forward |

unc-29 qPCR |

| PS372 | ACCTCGTAATTTCCATCGGCA | Reverse |

unc-29 qPCR |

| PS373 | ACCTCGTAATTTCCATCGGCA | Forward | unc-38 |

| qPCR | |||

| PS374 | ATCGCCGAACTGCTGAAAAA | Reverse | unc-38 |

| qPCR | |||

| PS398 | TTGCAAAGTATCTTTTGCTCACT | Forward | unc-63 |

| qPCR | |||

| PS399 | TCAGTAATGGGAGAATATCAAGGAA | Reverse | unc-63 |

| qPCR |

Table 2.

List of plasmids

| Serial no. | Plasmid no. | Plasmid |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | pBAB201 | Phpo-30::GFP |

| 2 | pBAB203 | Prab-3::hpo-30 gDNA |

| 3 | pBAB204 | Pmyo-3::hpo-30 gDNA |

| 4 | pBAB205 | Punc-17::hpo-30 gDNA |

| 5 | pBAB220 | Pmyo-3:: hpo-30 gDNA::mCherry |

| 6 | pBAB241 | nlg-1(RNAi) in L4440 |

| 7 | pBAB242 | hpo-30(RNAi) in L4440 |

Table 3.

List of integrated lines

| Serial no. | Integrated line no. | Plasmid | Source and reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | nuIs321 | Punc-17::mCherry | Josh Kaplan laboratory (Babu et al., 2011) |

| 2 | Punc-17::ChIEF | Punc-17::ChIEF | From Erik Jorgensen laboratory |

| 5 | nuIs160 | Punc-129::SYD-2::GFP | Josh Kaplan laboratory (Sieburth et al., 2005) |

| 4 | nuIs299 | Pmyo-3::ACR-16::GFP | Josh Kaplan laboratory (Babu et al., 2011) |

| 5 | hpIs3 | Punc-25::SYD-2::GFP | CGC |

| 6 | nuIs283 | Pmyo-3::UNC-49::GFP | Josh Kaplan laboratory (Babu et al., 2011) |

| 7 | cwIs6 | CAM-1::GFP | Wayne Forrester laboratory (Kim and Forrester, 2003) |

| 8 | IhIs6 | Punc-25::mCherry | Erik Lundquist (Norris and Lundquist, 2011) |

| 9 | akIs38 | UNC-29::GFP | Villu Maricq laboratory (Francis et al., 2005) |

| 10 | kr98::YFP | UNC-63::YFP | Jean-Louis Bessereau laboratory (Rapti et al., 2011) |

| 11 | kr208::tagRFP | UNC-29::tagRFP | Jean-Louis Bassereau laboratory (Richard et al., 2013) |

| 12 | vjIs105 | Pnlg-1::NGL-1::GFP | Derek Sieburth laboratory (Staab et al., 2014) |

| 13 | juIs76 | Punc-25::GFP | Yishi Jin laboratory (Baran et al., 2010) |

| 14 | wyEx5333 | Phlh-1::NLG-1 | Kang Shen laboratory (Maro et al., 2015) |

Table 4.

List of strains

| Strain | Genotype | Comments | Figure(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAB 206 | hpo-30 | CGC, RB1657 (outcrossed 4×) | 1–8 |

| BAB 253 | IndEx205 (hpo-30; Punc17::HPO-30) | 1 | |

| BAB 254 | IndEx201 (Phpo-30::GFP) | 1 | |

| BAB 208 | IhIs6; IndEx201 (Phpo-30::GFP) | 1 | |

| BAB 211 | nuIs321; IndEx201 (Phpo-30::GFP) | 1 | |

| BAB 252 | IndEx204 (hpo-30; Pmyo-3::HPO-30) | 1, 4, and 5 | |

| BAB 251 | IndEx203 (hpo-30; Prab-3::HPO-30) | 1, 4, and 5 | |

| BAB 239 | hpo-30; Punc-17::ChIEF | 3 | |

| BAB 207 | hpo-30; nuIs321 | 2 | |

| BAB 205 | hpo-30; juIs76 | 2 | |

| BAB 209 | hpo-30; nuIs160 | 2 | |

| BAB 210 | hpo-30; hpIs3 | 2 | |

| BAB 249 | hpo-30; nuIs299 | 5 | |

| BAB 246 | hpo-30; UNC-63::YFP | 5 | |

| BAB 228 | hpo-30; akIs38 | 5 | |

| BAB 242 | CwIs6; UNC-29::tagRFP | 5 | |

| BAB 243 | hpo-30; CwIs6; UNC-29::tagRFP | 5 | |

| BAB 250 | hpo-30; nuIs283 | 5 | |

| BAB 232 | lev-8 | CGC, VC1041 (outcrossed 3×) | 5 |

| BAB 239 | hpo-30; lev-8 | 5 | |

| BAB 256 | IndEx220 akIs38; (Pmyo-3::HPO-30::mCherry) | 6 | |

| BAB 262 | nlg-1 | CGC, VC1416 (outcrossed 3×) | 7 and 8 |

| BAB 261 | nrx-1 | CGC, VC228 (outcrossed 4×) | 7 and 8 |

| BAB 241 | nrx-1 hpo-30 | 7 and 8 | |

| BAB 245 | hpo-30; nlg-1 | 7 and 8 | |

| BAB 247 | nlg-1; Punc-17::ChIEF | 8 | |

| BAB 248 | nrx-1; Punc-17::ChIEF | 8 | |

| BAB 257 | hpo-30; viIs105 | 8 | |

| BAB 275 | hpo-30; UNC-29::tagRFP | 8 | |

| BAB 276 | hpo-30; nlg-1; UNC-29::tagRFP | 8 | |

| BAB 277 | nlg-1; UNC-29::tagRFP | 8 |

Behavioral assays

Aldicarb assay.

Aldicarb assays were performed as described previously (Harada et al., 1994; Miller et al., 1996; Nurrish et al., 1999). Plates containing 1 mm aldicarb (Sigma-Aldrich; 33386) were prepared 1 d before the assay and allowed to dry at room temperature. Young adult animals (20–25) were picked and placed on aldicarb plates. The animals were scored for paralysis by gently prodding them after every 10 min with a pick, for up to 2 h. The assays were performed in triplicates with the experimenter being blind to the genotype of the animals. For simplicity, the percentage of animals that were paralyzed at the 100 min time point was plotted.

Levamsiole assay.

Tetramisole hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich; # L9756) solution was prepared in water and dissolved in nematode growth medium to a concentration of 0.6 mm. Young adults animals (20–25) were placed on levamisole-containing plates seeded with OP50 and were monitored for paralysis after every 10 min. The animals were scored for paralysis by tapping the plates on the bench as has been previously described (Gendrel et al., 2009; Rapti et al., 2011). Animals showing less than one body bend were scored as paralyzed. The assay was performed in triplicates with the experimenter being blind to the genotype of the animals. For simplicity, the percentage of animals that were paralyzed at the 100 min time point was plotted.

Muscimol assay.

Muscimol (Sigma-Aldrich; # G019) assays were performed as described previously (de la Cruz et al., 2003). Briefly, 10–12 animals were placed on plates containing 200 mm muscimol for 1 h, after which the C. elegans behavior was analyzed by recording their response to touch. The animals were scored according to their movement or the pattern of contraction and relaxation cycle of the body. The behavior of C. elegans was classified into five categories: 0, C. elegans did not contract or relax but moved away from the stimulus rapidly; 1, C. elegans contract and relax briefly and then move away from the stimulus; 2, animals contracted and relaxed while showing a small backward displacement; 3, C. elegans contracted and relaxed but failed to move; and 4, animals contracted and relaxed incompletely with no displacement. The assay was performed in triplicates with the experimenter being blind to the genotype of the animals.

Microscopy

The imaging was done using a Axio Imager Z2 with an Axiocam MRm camera (Carl Zeiss). For imaging experiments, the animals were immobilized using 30 mg/ml BDM on 2% agarose pads. The analysis of images was done using the ImageJ software. For quantitative analysis, the fluorescence intensity of ∼25 animals (actual number indicated at the base of each bar graph) was averaged and used to plot the graph using the Prism software (GraphPad). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. p values were based on Student's t test or one-way ANOVA. Images for muscle arms were acquired using the TCS SP8 confocal microscope (Leica), and the image processing was done using ImageJ software.

qPCR

The qPCR experiments were performed using total RNA extracted from mixed-stage animals using the RNA easy kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (QIAGEN). The RNA was transcribed to cDNA using the Transcriptor high-fidelity cDNA synthesis kit (Roche; # 05081955001). The qPCR was performed using SYBR Green master mix (QIAGEN; # 204141) using an Eppendorf thermal cycler.

Antibody production

The UNC-29 and UNC-38 antibodies were produced as previously described (Gally et al., 2004; Gendrel et al., 2009). Briefly, for the UNC-29 antibody, a DNA fragment encoding 348–431 amino acids of the UNC-29 gene was inserted into pGEX-5X and for the UNC-38 antibody, a DNA fragment encoding 375–418 amino acids of the UNC-38 gene was cloned in pGEX-5X. The GST::UNC-29 and GST::UNC-38 fusion proteins were then expressed in BL21 Escherichia coli cells and purified. This fusion protein was then injected into the rabbits, and rabbits were boosted with 100 μg each time. The antibody was then purified and used for experiments. The antibody production and purification were performed by Bioklone Biotech.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

For protein extraction, mixed-stage animals were grown and stored at −80°C until further use. While starting the protein extraction, ice-cold homogenization buffer was added to the C. elegans pellets. C. elegans lysate was prepared by grinding the animals in a mortar and pestle in presence of liquid nitrogen. The suspension was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove the debris. The supernatant was then centrifuged at high speed for 1 h at 4°C. The pellet was then dissolved in 100–500 μl of resuspension buffer as previously described (Gendrel et al., 2009). This fraction was then resolved on SDS-PAGE gel and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were then probed with the purified anti-UNC-29 (1:600) or anti-UNC-38 (1:1000) serum. Antirabbit secondary antibody (1:2000, IgG-AP # sc-2007, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used to probe the blot and detection was done using the Pierce Alkaline phosphatase substrate kit.

To perform the coimmunoprecipitation experiment, C. elegans-expressing HPO-30::mCherry in muscles was grown in multiple plates (40 plates of 90 mm diameter). The animals were collected using M9 buffer, and they were washed three times with the M9 buffer to get rid of the OP50. The protein was prepared using a previously described protocol (Gendrel et al., 2009). Next, 3 mg of protein sample was incubated with UNC-29 and UNC-38 antibodies at 4°C for 4 h; 50 μl of equilibrated protein A/G beads (Merck Millipore #16–125) was added to the lysate and further incubated for 3 h. Next, the beads were washed 5 times with ice-cold lysis buffer. The protein was then eluted in 30 μl of sample loading buffer by boiling for 5 min. Western blotting was performed using mCherry rat antibody (Molecular Probes # M11217) at 1:1000 dilution. We used HRP-labeled antirat secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:5000. Protein detection was done using the GE enhanced chemiluminescent detection reagent.

Electrophysiological recordings

Electrophysiology was done on dissected C. elegans as previously described (Hu et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2018). The C. elegans was superfused in an extracellular solution containing 127 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 26 mm NaHCO3, 1.25 mm NaH2PO4, 20 mm glucose, 1 mm CaCl2, and 4 mm MgCl2, bubbled with 5% CO2/95% O2 at 20°C. Whole-cell recordings were performed at −60 mV (reversal potential of GABAA receptors) for mEPSCs and 0 mV (reversal potential of AChRs) for mIPSCs. The internal solution contains 105 mm CH3O3SCs, 10 mm CsCl, 15 mm CsF, 4 mm MgCl2, 5 mm EGTA, 0.25 mm CaCl2, 10 mm HEPES, and 4 mm Na2ATP, adjusted to pH 7.2 using CsOH. Stimulus-evoked EPSCs were stimulated by placing a borosilicate pipette (51 μm) near the ventral nerve cord (one muscle distance from the recording pipette) and applying a 0.4 ms, 85 μA square pulse (WPI). To measure levamisole-activated currents, a puffing pipette (5–10 μm open size) containing 0.5 mm levamisole was placed at the end of the patched muscle, and a 100 ms 20 kPa pressure was applied via Picospritzer (Parker).

Statistical analysis

Statistical values for each set of genotypes compared through Student's t test are indicated as p, t, and df.

Results

Mutants of hpo-30, a claudin-like protein, are resistant to aldicarb

To understand the function of claudins at the NMJ, we screened through all available claudin mutants using the acetylcholine esterase inhibitor, aldicarb. Aldicarb causes an increase in the levels of acetylcholine and hence results in increased muscle contraction in the animal, which in turn leads to paralysis. Mutants with altered synaptic function show increased or decreased rates of paralysis compared with WT C. elegans (Miller et al., 1996; Sieburth et al., 2005; Vashlishan et al., 2008).

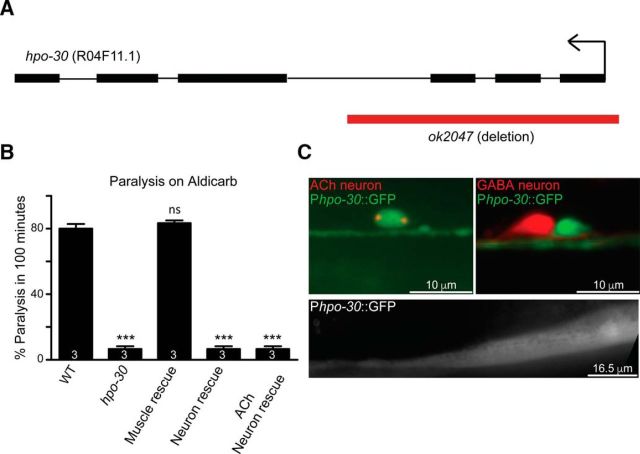

In this screen, we found that a deletion (likely null) mutant of hpo-30 (ok2047) that removes 1.2 kb of the coding region, including exons 1–3 showed an extremely resistant phenotype upon exposure to aldicarb compared with WT animals (WT and hpo-30, p = 0.0002, t = 22, df = 4; Fig. 1A,B). HPO-30 encodes a four-transmembrane domain protein with similarity to members of the claudin-like family of proteins.

Figure 1.

Mutants in hpo-30 are resistant to aldicarb. A, Schematic of the hpo-30 gene. Black boxes represent the coding exons. Red bar represents the ok2047 deletion. B, Aldicarb assay of WT, hpo-30 mutants, and site-specific rescue of HPO-30. Bar graphs represent the percentage of animals paralyzed at the 100 min time point. In all the aldicarb graphs, the number at the base of the bars indicates the number of times the assay was performed with 20–25 C. elegans used for each trial. Data are mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001. C, Transcriptional reporter of hpo-30 shows expression in cholinergic neurons and not in GABAergic neurons, which were identified by Punc-17::mCherry and Punc-25::mCherry, respectively. Phpo-30::GFP also shows expression in body-wall muscles. ns, not significant.

Previous studies have shown the expression of HPO-30 in FLP, PVD, tail, and ventral cord neurons and that it is required for stabilizing dendritic branching in PVD neurons (Smith et al., 2013). Because we were interested in understanding the role of HPO-30 at the NMJ, we planned to evaluate the expression of the hpo-30 promoter in motor neurons and/or body-wall muscles. To achieve this, we made a GFP transcriptional reporter containing a 3 kb upstream region of hpo-30 and analyzed the expression of this promoter fusion. We observed the expression of HPO-30 in the ventral cord motor neurons as previously reported, further diffuse expression was present in the body-wall muscles (data not shown; and Fig. 1C) (Smith et al., 2013). To identify the HPO-30-expressing neurons, we performed a double-labeling experiment and found that the GFP-tagged hpo-30 promoter showed coexpression with mCherry-labeled cholinergic neurons and not with GABAergic neurons (Fig. 1C).

Because the hpo-30 promoter showed expression in cholinergic neurons and body-wall muscle, we next went on to find the site of action of HPO-30. To achieve this, we expressed HPO-30 specifically in the body-wall muscles, pan-neuronally and in cholinergic neurons. The data from the rescue experiments indicated that the aldicarb resistance in hpo-30 mutants could be rescued only when HPO-30 was expressed specifically in the body-wall muscles (WT and hpo-30; Pmyo-3::HPO-30, p = 0.3910, t = 1, df = 3; Fig. 1B).

Because HPO-30 showed expression in presynaptic cholinergic neurons and postsynaptic body-wall muscles, we next wanted to see whether the mutants showed defects in synaptic development.

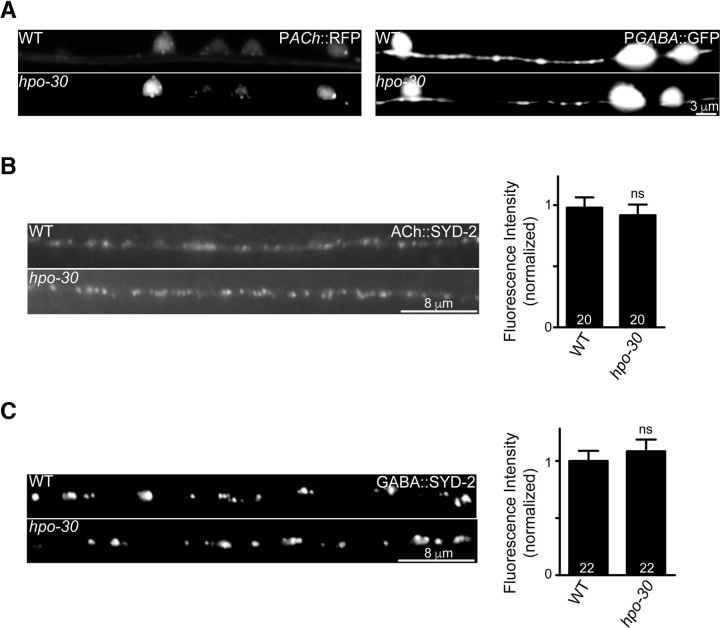

Synapse morphology is normal in hpo-30 mutants

The decreased responsiveness of hpo-30 mutant animals toward aldicarb could be due to altered neuronal or synapse development. To check for developmental defects in neurons and synapses, we went on to look at a set of neuronal and synaptic markers in the hpo-30 mutant animals. Loss of hpo-30 did not appear to have any obvious developmental defects on the cholinergic or GABAergic motor neurons (Fig. 2A). Further, both cholinergic and GABAergic synapses at the NMJ appeared to be formed normally as seen using the active zone marker α-liprin/SYD-2 expressed specifically in cholinergic or GABAergic neurons, respectively (WT and hpo-30, p = 0.6081, t = 0.5168, df = 41; Fig. 2B; and WT and hpo-30, p = 0.5299, t = 0.6331, df = 41; Fig. 2C). Together, these results suggest that the decreased rate of paralysis shown by hpo-30 mutant animals is unlikely to be due to developmental defects of neurons or synapses.

Figure 2.

hpo-30 mutants have normal neuromuscular synapses. A, Expression of Punc-17::mCherry and Punc-25::GFP in WT and hpo-30 mutant animals. B, Representative images and quantification for the active zone protein SYD-2 along the dorsal cord axons of cholinergic neurons in WT and hpo-30 C. elegans. C, Representative images and quantification for active zone protein SYD-2 in dorsal cord axons of GABAergic neurons in WT and hpo-30 animals. Data are mean ± SEM. ns, not significant.

hpo-30 mutants have normal synaptic vesicle release at the NMJ

The aldicarb resistance phenotype showed by hpo-30 mutants and the expression of Phpo-30::GFP in cholinergic neurons and body-wall muscles indicated a role for HPO-30 in either promoting the vesicle release machinery or maintaining the acetylcholine reception machinery. To assay synaptic transmission, we measured EPSCs and IPSCs from the body-wall muscles (Richmond, 2006; Hu et al., 2012). The amplitude and rate of endogenous EPSCs and IPSCs were unaltered in hpo-30 mutants (Fig. 3A–D: frequency WT and hpo-30, p = 0.8281, t = 0.2195, df = 24; amplitude, p = 0.5499, t = 0.6065, df = 24; Fig. 3C; WT and hpo-30 frequency, p = 0.6177, t = 0.5123, df = 12; and amplitude, p = 0.8981, t = 0.1308, df = 12; Fig. 3D). This suggests that synaptic transmission at the cholinergic and GABAergic NMJs is largely normal. Further, we looked at the muscle responsiveness by measuring the evoked currents and found that there were no significant changes in the amplitude and charge transfer of evoked EPSCs in the hpo-30 animals compared with WT controls (Fig. 3E: evoked EPSC amplitude WT and hpo-30, p = 0.9087, t = 0.1160, df = 22; and charge, p = 0.8852, t = 0.1461, df = 22; Fig. 3F). The C. elegans body-wall muscle possesses two types of cholinergic receptors: ACR-16 and LAChRs (Lewis et al., 1980; Fleming et al., 1997; Richmond and Jorgensen, 1999; Culetto et al., 2004; Touroutine et al., 2005; Towers et al., 2005). ACR-16 receptors account for ∼90% of the postsynaptic currents in C. elegans, and changes in ACR-16 levels affect the amplitude of the EPSCs and cause changes in the evoked EPSC current amplitudes (Francis et al., 2005; Touroutine et al., 2005; Babu et al., 2011). Hence, these data showing no significant changes in evoked EPSC amplitude suggest that HPO-30 does not appear to affect ACR-16 receptors. We next went on to further test whether HPO-30 is required for normal postsynaptic receptor function.

Figure 3.

Endogenous and evoked neurotransmitter release is normal in hpo-30 mutants. A, Representative trace of endogenous EPSC recordings from body-wall muscles of adult WT and hpo-30 animals. B, Representative trace of endogenous IPSC recordings from body-wall muscle of adult WT and hpo-30 mutants. C, Average frequency and average amplitude of EPSCs of WT and hpo-30 mutants. The numbers at the base of the bars indicate the number of animals recorded in all figures. D, Average frequency and average amplitude of IPSCs for WT and hpo-30 mutant C. elegans. E, Trace of stimulus-evoked response measured from the body-wall muscles of adult animals. F, Summary data of evoked currents in WT and hpo-30 mutants. Data are mean ± SEM.

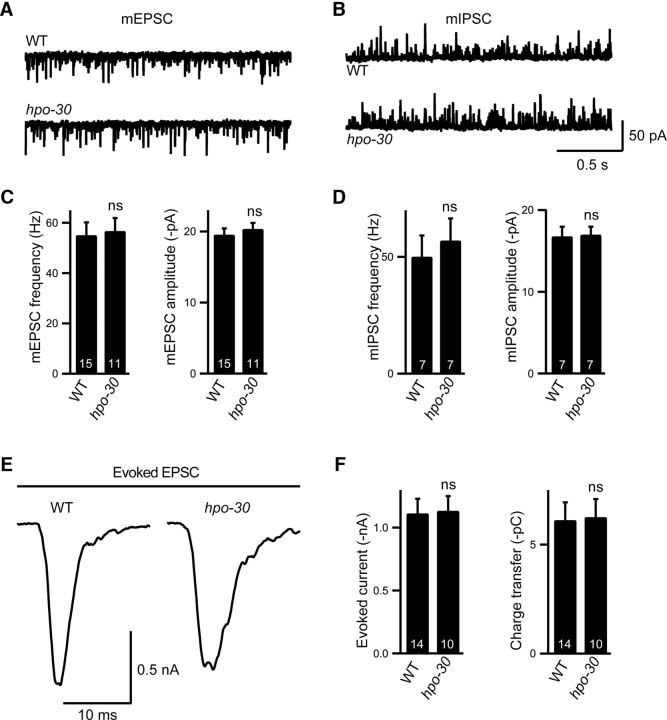

HPO-30 is required for normal LAChR-dependent functions

The decreased rate of paralysis of hpo-30 mutants in the presence of aldicarb and the ability to rescue this defect by expressing HPO-30 specifically in body-wall muscles suggest that HPO-30 could function in the body-wall muscles for maintaining normal aldicarb response.

The C. elegans NMJ expresses receptors that respond to both cholinergic and GABAergic neurotransmitters functioning at the body-wall muscles (Richmond and Jorgensen, 1999). To explore the possibility that HPO-30 could affect receptor function at the body-wall muscles and thereby show altered aldicarb sensitivity, we performed pharmacological experiments to assay for defects in cholinergic and GABAergic receptors.

As stated previously, the cholinergic receptors include two classes of nicotinic AChRs: the homomeric AChR/ACR-16 receptors and the heteropentameric LAChRs, which are activated specifically by the drug levamisole (Lewis et al., 1980; Fleming et al., 1997; Richmond and Jorgensen, 1999; Culetto et al., 2004; Touroutine et al., 2005; Towers et al., 2005). Levamisole is an agonist of the AChR and causes muscle hypercontraction, leading to the paralysis of the animals. Mutants lacking the ACR-16 receptors have a mild change in aldicarb sensitivity, whereas mutants lacking the LAChRs exhibit strong resistance to aldicarb (Lewis et al., 1980; Daniels et al., 2000; Babu et al., 2011), suggesting that HPO-30 may regulate the functioning of LAChRs. To see whether hpo-30 mutants affected LAChRs, we performed a levamisole assay using the hpo-30 mutant animals (Lewis et al., 1980; Gally et al., 2004). Mutants in hpo-30 showed resistance to paralysis in the presence of levamisole (WT and hpo-30, p < 0.0001, t = 20.12, df = 4); this resistance was rescued by the expression of HPO-30 specifically in the body-wall muscles and not in motor neurons (WT and hpo-30; Pmyo-3::HPO-30, p = 0.6779, t = 0.4472, df = 4; Fig. 4A). This experiment indicated that HPO-30 could be affecting LAChRs at the body-wall muscle. We also performed assays for defects in the GABA receptor at the NMJ using the drug muscimol, which is a GABA receptor agonist (de la Cruz et al., 2003). In the presence of muscimol, we saw no difference between WT and hpo-30 mutant animals, indicating that loss of hpo-30 does not appear to affect GABA receptors (Severity 2, p = 1.00, t = 0.0, df = 2; Severity 3, p = 0.2929, t = 1.414, df = 2; Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

hpo-30 mutants show defects in LAChR functions. A, Levamisole-induced paralysis of WT, hpo-30 mutants, and site-specific rescue of HPO-30. Graph represents percentage of paralyzed animals at the 100 min time point. B, Behavior of WT and hpo-30 mutant animals in the presence of muscimol. Graph represents the fraction of C. elegans, which displayed the three levels of severity of behavior in the presence of muscimol. The behavior of the animals was classified onto five categories, of which both WT and hpo-30 animals showed only three of the phenotypes: 1, C. elegans contract and relax briefly and then move away from the stimulus; 2, animals contract and relax while at the showing a small backward displacement; and 3, C. elegans contract and relax but fail to move backwards. C, Response to pressure ejection of levamisole on voltage-clamped body-wall muscle cells in animals with the following genotypes: WT, hpo-30, and muscle-specific rescue and neuron-specific rescue of HPO-30. D, Graph represents the amplitude of levamisole-activated currents for the animals recorded in C. Data are mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001.

Because all our data so far indicate that hpo-30 does not appear to affect either the amplitude of the EPSCs or the evoked currents, we hence reasoned that HPO-30 was unlikely to be affecting ACR-16 levels at the NMJ (Fig. 3A,C,E,F).

To better understand the functional consequence of this decreased sensitivity toward levamisole, we recorded the levamisole puff response of body-wall muscles in hpo-30 mutant animals using previously described protocols (Richmond, 2006; Hu et al., 2012). We observed a large decrease in the amplitude of the currents in hpo-30 mutants compared with WT animals (WT and hpo-30, p < 0.0001, t = 29.37, df = 14). Again, this decrease in levamisole puff response was rescued by expressing HPO-30 in the body-wall muscles (WT and hpo-30; Pmyo-3::HPO-30, p = 0.5674, t = 0.5868, df = 13; Fig. 4C,D), whereas HPO-30 expression pan-neuronally could not rescue this phenotype (WT and hpo-30; Prab-3::HPO-30, p < 0.0001, t = 27.58, df = 12; Fig. 4C,D). The above data strongly suggest that HPO-30 functions in the body-wall muscles to maintain the function of LAChRs. These results prompted us to look at LAChR levels at the NMJ.

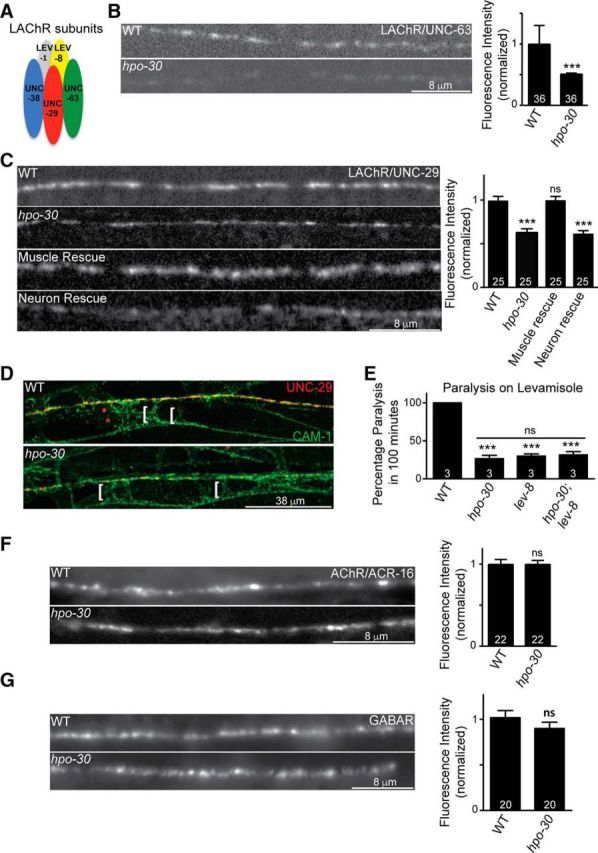

HPO-30 is involved in the maintenance of LAChR levels at the NMJ

Decreased sensitivity of hpo-30 mutants to levamisole could be the result of altered expression or function of LAChRs. The LAChRs are pentameric receptors composed of five subunits: UNC-29, UNC-63, UNC-38, LEV-8, and LEV-1 (Fig. 5A) (Fleming et al., 1997; Richmond and Jorgensen, 1999; Culetto et al., 2004; Towers et al., 2005). We first went on to look at the expression of fluorescently tagged LAChR/UNC-29 and LAChR/UNC-63 receptor subunits in the hpo-30 mutant animals (Francis et al., 2005; Rapti et al., 2011). We found that hpo-30 mutants showed a significant decrease in the fluorescence intensity of both UNC-63::YFP and UNC-29::GFP at the NMJ (WT and hpo-30, p = 0.0004, t = 3.450, df = 66; Fig. 5B; WT and hpo-30, p < 0.0001, t = 5.973, df = 43; Fig. 5C). The decreased levels of UNC-29::GFP were completely rescued by specifically expressing HPO-30 in the body-wall muscles (WT and hpo-30; Pmyo-3::HPO-30, p = 0.9668, t = 0.0418, df = 44) but not in the neurons of the animals (WT and hpo-30; Prab-3::HPO-30, p = 0.0001, t = 6.234, df = 40; Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Mutants in hpo-30 show a decrease in synaptic LAChR abundance. A, Diagram of five distinct subunits of the LAChRs. B, Distribution of UNC-63::YFP at the NMJ in WT and hpo-30 animals and the fluorescence intensity of UNC-63::YFP in WT and hpo-30. The number of animals analyzed is indicated at the base of the bar graph for all graphs. C, Representative images and quantification for distribution of UNC-29::GFP at the NMJ in WT, hpo-30, and HPO-30 rescue lines. D, Localization of UNC-29::RFP and CAM-1::GFP at the NMJ in WT and hpo-30 animals. Brackets indicate the muscle arms. E, Levamisole-induced paralysis in WT, hpo-30, lev-8, and hpo-30;lev-8 mutants at the 100 min time point. F, Representative images and quantification for the distribution of ACR-16::GFP at the NMJ in WT and hpo-30 animals. G, Representative images and quantification for the distribution of UNC-49::GFP at the NMJ in WT and hpo-30 mutants. Data are mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001.

At the C. elegans NMJ, body-wall muscles extend projections called muscle arms to the nerve cord where they form en passant synapses with axons of motor neurons (White et al., 1986). The decrease in the fluorescence of LAChR/UNC-29 at the neuromuscular synapse in hpo-30 mutant animals could be because the receptors are not localized at the synapse but are localized extrasynaptically in the regions of the muscle arms. To test whether LAChR/UNC-29 was localized to the body-wall muscle arms in the mutants, we studied the localization of LAChR/UNC-29 at extrasynaptic regions using a strain in which the fluorescent protein tagRFP is introduced into the genomic locus of UNC-29 (Robert and Bessereau, 2007; Richard et al., 2013). We found that, in this line as well, there was a marked decrease in synaptic LAChR/UNC-29 in hpo-30 mutants (representative image in Fig. 5D), but no mislocalization of the receptors in the region of the body-wall muscle arms, indicated with CAM-1::GFP, was seen (Fig. 5D, white brackets). Together, these results suggest that loss of hpo-30 decreases the synaptic abundance of LAChRs, and it is unlikely that the decrease in the LAChR levels is due to the mislocalization of the receptors at the site of muscle arms.

To further understand the function of HPO-30 in maintaining LAChRs at the synapse, we analyzed the behavior of hpo-30 mutants, lev-8 mutants, and hpo-30;lev-8 double mutants in the presence of levamisole. The resistance phenotypes of both single mutants and the double mutant were indistinguishable (hpo-30 and hpo-30;lev-8, p = 0.4674, t = 0.8018, df = 4; Fig. 5E), thus suggesting that another subunit of LAChR functions in the same pathway as HPO-30.

Next, we wanted to test whether HPO-30 affected other receptors; we assayed for defects in the fluorescently tagged homomeric AChR/ACR-16 and the GABAAR/UNC-49 (Bamber et al., 1999; Babu et al., 2011). It was found that the levels of ACR-16::GFP and UNC-49::GFP were not affected by the absence of hpo-30 (WT and hpo-30, p = 1.0000, t = 0.000, df = 42; Fig. 5F; and WT and hpo-30, p = 0.2650, t = 1.135, df = 32; Fig. 5G).

These results suggest that HPO-30 function in muscles to maintain normal LAChR levels at the C. elegans NMJ. We next wanted to test whether HPO-30 affected the expression levels of LAChRs.

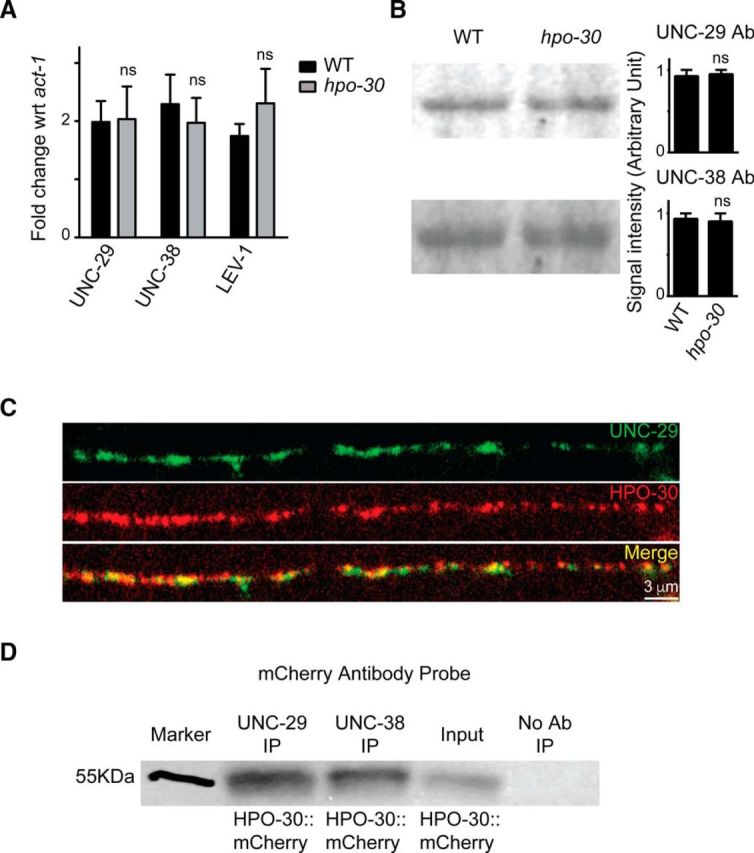

Mutants of hpo-30 show normal expression of LAChR subunits

Our experiments so far suggest that hpo-30 mutant animals show a decrease in LAChR levels at the NMJ. The decrease in the levels of LAChRs could be the result of decrease in the expression of genes coding for LAChR subunits. To check whether HPO-30 is required for gene expression, we compared the expression levels of LAChR subunits unc-29, unc-63, and unc-38 in WT and hpo-30 mutant background by performing qRT-PCR. There was no apparent difference in the transcript levels of the three subunits of LAChR tested in WT and hpo-30 mutants (unc-29, p = 0.9526, t = 0.06717, df = 2; unc-38, p = 0.6726, t = 0.4900, df = 2; and lev-1, p = 0.4612, t = 0.9046, df = 2; Fig. 6A). We also went on to quantitate the total amounts of UNC-29 and UNC-38 proteins in the animals by quantitative Western blotting using antibodies against UNC-29 and UNC-38, respectively. Again, we found that there was no difference between the UNC-29 and UNC-38 protein levels in WT and hpo-30 mutant animals (UNC-29, p = 0.8076, t = 0.2773, df = 2; and UNC-38, p = 0.8188, t = 0.2606, df = 2; Fig. 6B). These results indicate that HPO-30 is unlikely to be required for the transcription or the translation of the LAChR subunits. To further analyze the association between HPO-30 and LAChRs, we analyzed the localization of mCherry tagged HPO-30 expressed in body-wall muscles and observed overlapping expression with LAChRs/UNC-29 postsynaptically at the NMJ (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

The expression level of LAChRs is unaffected in hpo-30 mutants. A, qPCR experiments comparing the levels of unc-29, unc-38, and unc-63 in WT and hpo-30 mutant animals. B, Images and graphs of Western blots indicating the protein levels of UNC-29 and UNC-38 in WT and hpo-30 C. elegans. Data are mean ± SEM. C, Distribution of HPO-30::mCherry and UNC-29::GFP in muscles. D, Coimmunoprecipitation of HPO-30::mCherry using anti-UNC-29 and anti-UNC-38 antibodies. As a control, the protein extracts are allowed to incubate with beads only without the antibody. The coimmunoprecipitated complex was then probed with an anti-mCherry antibody.

As HPO-30 showed genetic interaction with the LAChR subunit LEV-8 and also colocalized with UNC-29 (Figs. 5E, 6C), we hypothesized that HPO-30 might be functioning through a physical interaction where it may complex with LAChR subunits. To test this, we performed a coimmunoprecipitation experiment using C. elegans expressing HPO-30::mCherry in muscles. We used anti-UNC-29 and anti-UNC-38 to find the probable interaction between these LAChRs and HPO-30. Upon blotting with an antibody against mCherry, we found that HPO-30::mCherry was pulled down with UNC-29 and UNC-38 antibodies. As a control, we used protein lysate incubated with beads only and no antibody (Fig. 6D). These results demonstrate that HPO-30 shows a possible association with the LAChRs UNC-29 and UNC-38 and shows colocalization with UNC-29 at the NMJ. Together, these data indicate that HPO-30 may be required for stabilizing the LAChRs at the NMJ.

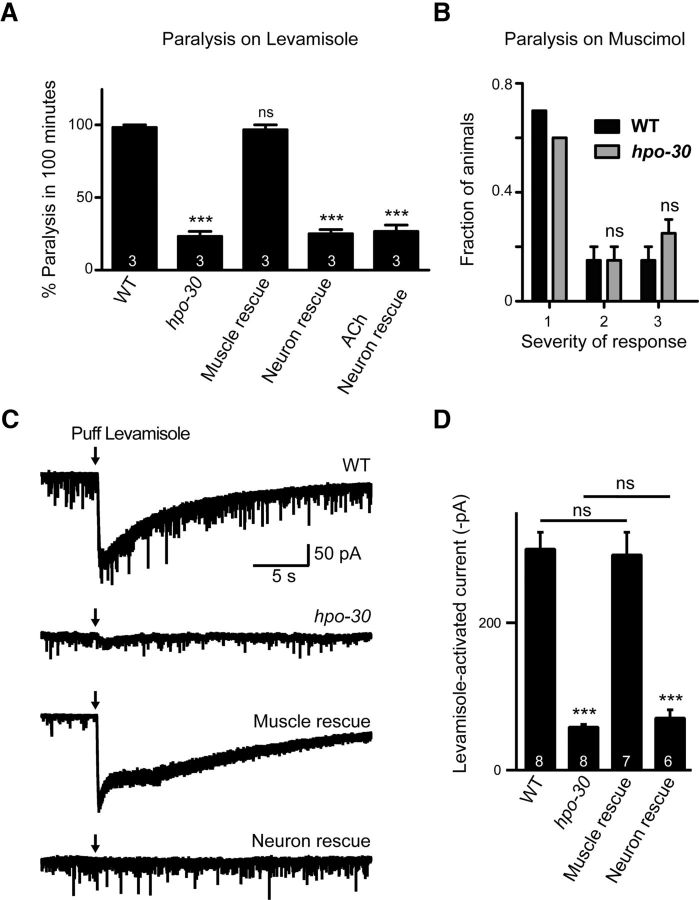

HPO-30 functions through Neuroligin to maintain normal levamisole puff response

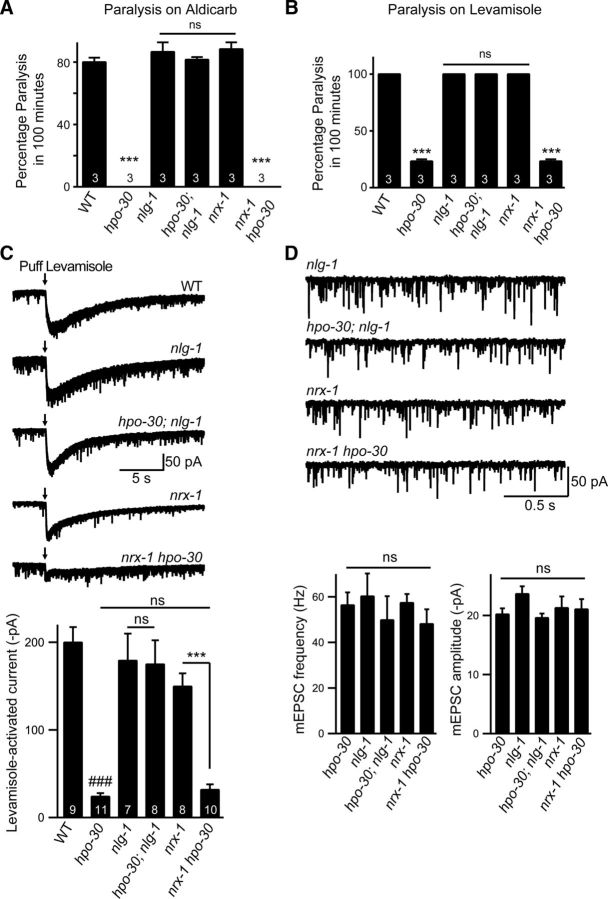

The body-wall muscles in C. elegans cluster GABAergic receptors apposing GABAergic inputs and LAChRs and ACR-16 receptors apposing cholinergic inputs (White et al., 1976, 1986; Richmond and Jorgensen, 1999). Recent studies have shown that Neurexin (NRX-1) and NLG-1 are required for clustering GABAA receptors at the NMJ (Maro et al., 2015; Tu et al., 2015). To test whether HPO-30 could function through NRX-1 and/or NLG-1, we analyzed the behavioral responses of hpo-30;nlg-1 and nrx-1;hpo-30 double mutants toward aldicarb and levamisole along with their respective controls (i.e., single mutants for hpo-30, nlg-1, and nrx-1). Surprisingly, we found that the hpo-30;nlg-1 mutants, but not the nrx-1;hpo-30 mutants, could completely suppress the resistance to aldicarb and levamisole phenotype that was seen in the hpo-30 mutants (aldicarb assay; WT and hpo-30;nlg-1, p = 0.6433, t = 0.50, df = 4; Fig. 7A). However, nlg-1 and nrx-1 single mutants showed phenotypes similar to WT animals on aldicarb and levamisole (WT and nlg-1, p = 0.3739, t = 1.000, df = 4; and WT and nrx-1, p = 0.1890, t = 1.581, df = 4). RNAi knockdown of nlg-1 and hpo-30 also confirmed our experiments performed with genetic mutants (data not shown).

Figure 7.

HPO-30 functions through NLG-1 to maintain LAChR function. A, Percentage paralysis of animals at the 100 min time point in WT (80%), hpo-30 (0%), nlg-1 (90%), nrx-1 (90%), hpo-30;nlg-1 (80%), and nrx-1 hpo-30 (0%) in the presence of aldicarb. B, Percentage paralysis of animals at 100 min in WT (100%), hpo-30 (25%), nlg-1 (100%), nrx-1 (100%), hpo-30;nlg-1 (100%), and nrx-1 hpo-30 (25%) upon exposure to levamisole. C, Currents recorded from voltage-clamped body-wall muscles in response to pressure-ejected levamisole in WT, nlg-1, hpo-30;nlg-1, nrx-1, and nrx-1 hpo-30. Black arrow indicates the time of application of levamisole and summary data for levamisole-puff currents. D, Representation of endogenous EPSCs recorded from body-wall muscles of adult C. elegans for the following genotypes: nlg-1, hpo-30;nlg-1, nrx-1, and nrx-1;hpo-30 and graphs showing average frequency and amplitude of EPSCs recorded. Data are mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, ###p < 0.001.

To further understand the role of NLG-1 in maintaining postsynaptic LAChRs, we performed levamisole-puff response-based electrophysiological analysis on the hpo-30;nlg-1 and the nrx-1;hpo-30 double mutants. Again, we found that nlg-1 and not nrx-1 could completely suppress the loss of levamisole puff response of hpo-30 mutants (WT and hpo-30, p < 0.0001, t = 11.32, df = 18; WT and nlg-1, p = 0.5356, t = 0.6350, df = 14; WT and nrx-1, p = 0.0403, t = 2.244, df = 15; WT and hpo-30;nlg-1, p = 0.4315, t = 0.8084, df = 15; WT and nrx-1 hpo-30, p < 0.0001, t = 9.911, df = 17; Fig. 7C).

We also recorded the endogenous EPSCs from the muscles in hpo-30;nlg-1 and nrx-1 hpo-30 mutant lines along with the single mutant controls and found that both the frequency and amplitude of the postsynaptic current were not significantly different from the single mutants (EPSC frequency; hpo-30 and nlg-1, p = 0.4122, t = 0.8419, df = 16; hpo-30 and hpo-30;nlg-1, p = 0.5368, t = 0.6322, df = 15; EPSC amplitude; hpo-30 and nlg-1, p = 0.0328, t = 2.336, df = 16; hpo-30 and hpo-30;nlg-1, p = 0.6583, t = 0.4513, df = 15; Fig. 7D). Together, these results suggest that NLG-1 and NRX-1 are unlikely to be required for the functioning of ACR-16 receptors at the NMJ.

Our results indicate that HPO-30 could function through NLG-1 to maintain the LAChR-dependent functions at the NMJ.

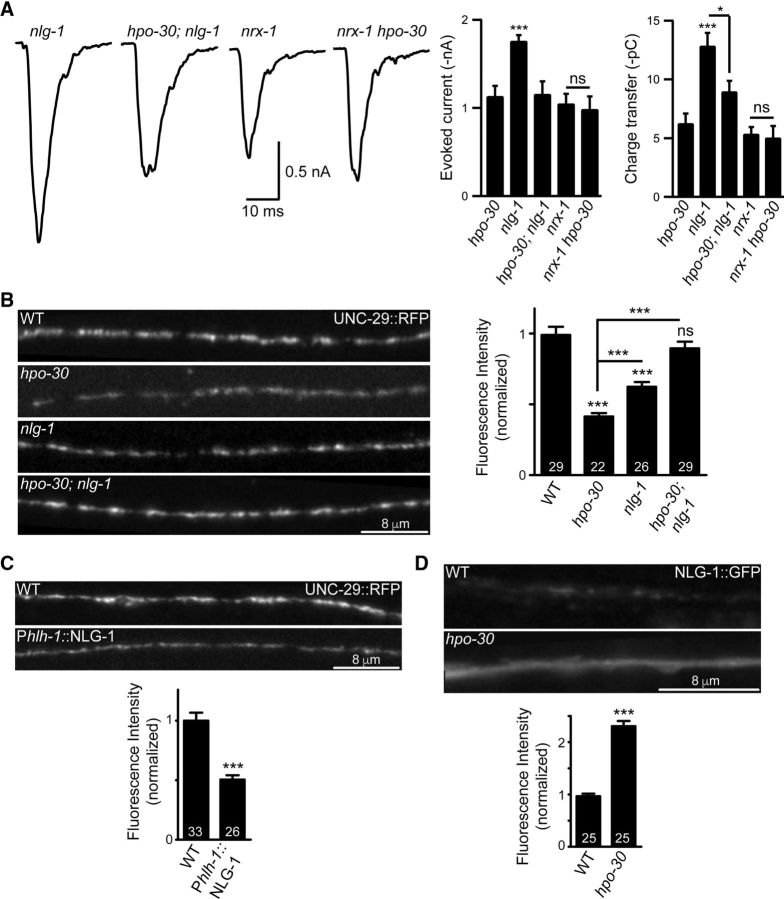

NLG-1 functions downstream of HPO-30

Our data so far indicate that loss of nlg-1 could suppress the hpo-30 mutant phenotype. We also analyzed the stimulus-evoked muscle responsiveness in nlg-, hpo-30, and hpo-30;nlg-1 mutants. We found that the stimulus-evoked currents in the double mutants were also similar to the control values (evoked currents; hpo-30 and nlg-1, p = 0.0007, t = 4.203, df = 16; and hpo-30 and hpo-30;nlg-1, p = 0.9020, t = 0.1253, df = 14; charge transfer; hpo-30 and nlg-1, p = 0.0002, t = 4.761, df = 16; and hpo-30 and hpo-30;nlg-1, p = 0.0590, t = 2.055, df = 14; Fig. 8A).

Figure 8.

NLG-1 functions downstream of HPO-30. A, Stimulus-evoked responses measured from the body-wall muscles of nlg-1, hpo-30;nlg-1, nrx-1, and nrx-1 hpo-30 animals and summary data for amplitude of evoked currents and charge transfer. B, Representative images and quantification for UNC-29::tagRFP in WT, hpo-30, nlg-1, and hpo-30;nlg-1. C, Representative images and quantification for UNC-29::tagRFP in WT and NLG-1-overexpressing animals. D, Representative images and quantification for NLG-1::GFP in WT and hpo-30 mutant C. elegans. Data are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

As all the previous results indicate that the absence of nlg-1 and hpo-30 could affect LAChR levels at the NMJ, we went on to examine the LAChR/UNC-29 levels in the hpo-30;nlg-1 double mutants. We analyzed the expression of UNC-29::tagRFP in hpo-30, nlg-1, and hpo-30;nlg-1 genetic backgrounds. We observed a significant decrease in the florescence intensity of UNC-29 at the NMJ in the hpo-30 mutant background (WT and hpo-30, p < 0.0001, t = 8.283, df = 49; Fig. 8B). However, in the hpo-30;nlg-1 double mutants, the florescence intensity was comparable with WT animals (WT and hpo-30;nlg-1, p = 0.2109, t = 1.269, df = 56; Fig. 8B). These results further indicate that nlg-1 suppresses the hpo-30 mutant phenotype to WT levels of LAChR/UNC-29 at the NMJ. Surprisingly, we also see a significant decrease in the LAChR/UNC-29 receptor levels in nlg-1 mutants (WT and nlg-1, p < 0.0001, t = 5.3089, df = 53; Fig. 8B), which we are unable to explain, as there is no significant change in the levamisole puff response in these animals (Fig. 7C). This change in the UNC-29 receptor levels at the NMJ in the absence of nlg-1 may indicate that NLG-1 could have a possible function in maintaining the LAChRs at the NMJ.

Our data suggest that elevated NLG-1 levels could result in decreased LAChRs at the NMJ. To verify this hypothesis, we looked at the expression of LAChR/UNC-29 after overexpressing NLG-1 in muscles. We found that there is a marked reduction in the UNC-29::tagRFP levels at the NMJ compared with WT control animals (p < 0.0001, t = 5.818, df = 57; Fig. 8C).

Finally, we wanted to test whether HPO-30 is required for maintaining NLG-1 levels at the NMJ. To do this, we imaged NLG-1::GFP in WT animals and in hpo-30 mutants. We found a significant increase in NLG-1 at the NMJ in hpo-30 mutants (p < 0.0001, t = 12.55, df = 46; Fig. 8D). These experiments further strengthened our hypothesis that NLG-1 could function downstream of HPO-30. Expression of HPO-30 is required to maintain WT levels of NLG-1 at the synapse, and loss of hpo-30 shows an aberrant increase in the synaptic NLG-1 levels. Together, our data strongly suggest that HPO-30 maintains LAChR levels at the NMJ and is functioning through NLG-1 to maintain its function at the neuromuscular synapse.

Discussion

Neurotransmission occurs at specialized points of contacts between the presynaptic neuron and the postsynaptic neuron or muscle. The signaling at the NMJ demonstrates a high level of subcellular complexity, and we are still to get a clear understanding of the NMJ components and their signaling mechanisms. In this study, we set out to determine the function of a C. elegans claudin-like molecule HPO-30 at the NMJ. Our results indicate that the expression and function of HPO-30 in the body-wall muscles are required to maintain normal LAChR receptor levels at the NMJ. Mutants lacking this protein exhibit resistance to cholinergic but not GABAergic agonists, indicating that HPO-30 affects AChRs and not GABARs.

In C. elegans, two types of AChRs are present at the NMJ. Pharmacologically, one is preferentially gated by levamisole (LAChRs) and the other by nicotine (nAChR). The kinetics and the mechanism of regulation and clustering of these receptors are very different (Richmond and Jorgensen, 1999; Francis et al., 2005; Boulin et al., 2008, 2012; Simon et al., 2008; Gendrel et al., 2009; Babu et al., 2011; Rapti et al., 2011; Jensen et al., 2012; Richard et al., 2013; Briseño-Roa and Bessereau, 2014; Pinan-Lucarré et al., 2014; Pierron et al., 2016; Pandey et al., 2017). Because loss of LAChRs causes resistance of the animal to levamisole, genetic screens based on levamisole-induced paralysis have contributed to the identification of proteins involved in functioning or assembly of LAChRs (Lewis et al., 1980; Fleming et al., 1997).

Previously, claudin-like proteins have been implicated in regulating structural aspect of the C. elegans nervous system. NSY-4 has been shown to affect AWC neuron specification by regulating calcium channels (Vanhoven et al., 2006), whereas HPO-30 has been implicated in governing dendritic branching in PVD neurons (Smith et al., 2013).

Our studies highlight the role of HPO-30 for the proper localization and hence activity of LAChRs while leaving the nAChR/ACR-16 physiology unaffected. Our data also indicate a possible association between HPO-30 and LAChRs as we show that HPO-30 coimmunoprecipitates with LAChR subunits UNC-38 and UNC-29. Together, these results suggest that HPO-30 could have a role in the trafficking, assembly, stability, or clustering of the levamisole sensitive receptors at the C. elegans NMJ. Further experiments would be required to pinpoint the exact function of HPO-30 in LAChR maintenance.

Our results add to the growing body of work on the role of claudins in the nervous system, where we show that a claudin-like molecule acts at the neuromuscular synapse to maintain normal LAChR localization and function at the C. elegans NMJ.

The biogenesis and assembly of ionotropic receptors are a multistep process. Multiple proteins are involved in the folding, generation of membrane topology, and assembly of subunits into pentamers, trafficking and clustering of AChRs. The ligand-gated ion channels require auxiliary subunits for their trafficking, assembly, and function (for review, see Green, 1999; Keller and Taylor, 1999). Auxiliary proteins required for functioning and assembly of LAChRs in C. elegans include RIC-3, UNC-50, UNC-74, NRA-2, NRA-4, and RSU-1. RIC-3 and UNC-50 are required for the efficient assembly, maturation, and trafficking of receptors from ER (Halevi et al., 2002; Eimer et al., 2007; Boulin et al., 2008; Jospin et al., 2009). Recently, NRA-2/Nicalin (Nicastrin-like protein), NRA-4/nodal modulator, and RSU-1 are proposed to regulate LAChRs subunit composition, stoichiometry, and distribution (Almedom et al., 2009; Pierron et al., 2016). LEV-9, LEV-10, and OIG-4 serve as an extracellular scaffold that forms a physical complex with the LAChRs and localize them at the synapse (Gendrel et al., 2009; Rapti et al., 2011; Briseño-Roa and Bessereau, 2014). Our work on HPO-30 might help in understanding the mechanism that regulates receptor clustering or localization at the synapse. In the C. elegans nervous system, acetylcholine serves as the main excitatory neurotransmitter, the presence of multiple auxiliary proteins might represent a means to increase the functional repertoire of ionotropic AChRs. It will be interesting to understand how HPO-30 functions with other modulators in selectively regulating levamisole-sensitive ion channels.

Finally, we have identified NLG-1 as an important molecule in maintaining LAChRs through HPO-30 at the NMJ. Mutants in nlg-1 have been previously shown to have defects in GABAA receptor clustering and for normal retrograde signaling across the NMJ in C. elegans (Hu et al., 2012; Maro et al., 2015; Tu et al., 2015; Tong et al., 2017). A previous study by Hu et al. (2012) has shown that nrx-1 and nlg-1 inhibit the retrograde signal induced by the microRNA mir-1 and that this inhibition is mediated by the presynaptic protein Tomosyn. Our data indicate that, unlike the other two components involved in retrograde signaling (i.e., nlg-1 and tom-1), hpo-30 does not appear to affect the secretion of synaptic vesicles. Although these experiments indicate that HPO-30 may not be involved in the retrograde signaling pathway, further experiments delineating the role of HPO-30 in presynaptic cholinergic neurons may help get more insight on possible presynaptic functions of HPO-30 at the NMJ. We further show that NLG-1 levels are negatively regulated by HPO-30 and that nlg-1;hpo-30 mutants suppress the hpo-30 mutant phenotype and show behaviors similar to nlg-1 mutant animals, indicating that NLG-1 is likely to be functioning downstream of HPO-30. Further, our data also suggest a possible association between HPO-30 and the LAChR receptor subunits. Together, our results suggest that HPO-30 negatively regulates NLG-1 levels, which in turn appears to antagonize LAChR clustering at the synapse. Further experiments could allow for more mechanistic insights into the function of HPO-30 and NLG-1 function at the NMJ.

A growing body of evidence suggests that cell adhesion molecules present at the synapse are not merely structural components, but they are actively involved in regulation and modification of synapse function, synapse formation, and synaptic receptor function (for review, see Dalva et al., 2007). The claudin family of proteins are known to interact with the actin cytoskeleton via other proteins (for review, see Sawada et al., 2003). The actin cytoskeleton acts as an important regulator of synapse assembly and organization (for review, see Dillon and Goda, 2005). The postsynaptic receptor organization and maintenance are dependent on number of proteins, including cell adhesion proteins and PDZ domain containing proteins (for review, see Sheng and Hoogenraad, 2007). The PDZ domain containing intracellular C-terminal domain of NLG-1 facilitates the binding of postsynaptic scaffold proteins (Irie et al., 1997; Dresbach et al., 2004). These proteins interact directly or indirectly with the actin cytoskeleton and hence could regulate receptor organization (for review, see Sheng and Kim, 2011). One possible outcome of HPO-30 function via NLG-1 could be modulation of the actin cytoskeleton, which in turn could allow for changes in ion channel localization at the synapse.

The genetic interaction of HPO-30 with the synaptic cell adhesion protein NLG-1 might serve as a link between cell adhesion and the regulation of ion channel. Our results add to the evidence that cell adhesion molecules can have multiple functions at the synapse.

Footnotes

WormBase was supported by National Human Genome Research Institute Grant U41 HG002223, U.S. National Institutes of Health, United Kingdom Medical Research Council, and United Kingdom Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. The Caenorhabditis Genetics Center Minneapolis was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). P.S. was supported by an Indian Council of Medical Research fellowship and WT-DBT India Alliance fellowship to K.B., V.T. was supported by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research for a graduate fellowship. K.B. is an Intermediate Fellow of the Wellcome Trust-DBT India Alliance (Grant IA/I/12/1/500516). K.B. was also supported by DBT-IYBA Grant BT/05/IYBA/2011 and Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Mohali. Z.H. was supported by NHMRC Project Grant APP1122351 and ARC Discovery Project Grant DP160100849. All vectors used in this study were obtained from Addgene. We thank the members of the K.B. laboratory for comments on the manuscript; Jean-Louis Bessereau, Erik Jorgensen, Wayne Forrester, Josh Kaplan, Erik Lundquist, Villy Maricq, Kang Shen and Derek Sieburth for strains; Josh Kaplan for multiple marker lines; Ankit Negi for routine help; the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Mohali Confocal facility for the use of the confocal microscope; WormBase; and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Almedom RB, Liewald JF, Hernando G, Schultheis C, Rayes D, Pan J, Schedletzky T, Hutter H, Bouzat C, Gottschalk A (2009) An ER-resident membrane protein complex regulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit composition at the synapse. EMBO J 28:2636–2649. 10.1038/emboj.2009.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelow S, Ahlstrom R, Yu AS (2008) Biology of claudins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295:F867–F876. 10.1152/ajprenal.90264.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arikkath J, Campbell KP (2003) Auxiliary subunits: essential components of the voltage-gated calcium channel complex. Curr Opin Neurobiol 13:298–307. 10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00066-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano A, Asano K, Sasaki H, Furuse M, Tsukita S (2003) Claudins in Caenorhabditis elegans: their distribution and barrier function in the epithelium. Curr Biol 13:1042–1046. 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00395-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu K, Hu Z, Chien SC, Garriga G, Kaplan JM (2011) The immunoglobulin super family protein RIG-3 prevents synaptic potentiation and regulates wnt signaling. Neuron 71:103–116. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamber BA, Beg AA, Twyman RE, Jorgensen EM (1999) The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-49 locus encodes multiple subunits of a heteromultimeric GABA receptor. J Neurosci 19:5348–5359. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05348.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baran R, Castelblanco L, Tang G, Shapiro I, Goncharov A, Jin Y (2010) Motor neuron synapse and axon defects in a C. elegans alpha-tubulin mutant. PLoS One 5:e9655. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulin T, Gielen M, Richmond JE, Williams DC, Paoletti P, Bessereau JL (2008) Eight genes are required for functional reconstitution of the Caenorhabditis elegans levamisole-sensitive acetylcholine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:18590–18595. 10.1073/pnas.0806933105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulin T, Rapti G, Briseño-Roa L, Stigloher C, Richmond JE, Paoletti P, Bessereau JL (2012) Positive modulation of a cys-loop acetylcholine receptor by an auxiliary transmembrane subunit. Nat Neurosci 15:1374–1381. 10.1038/nn.3197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77:71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briseño-Roa L, Bessereau JL (2014) Proteolytic processing of the extracellular scaffolding protein LEV-9 is required for clustering acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem 289:10967–10974. 10.1074/jbc.C113.534677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calahorro F, Ruiz-Rubio M (2012) Functional phenotypic rescue of Caenorhabditis elegans neuroligin-deficient mutants by the human and rat NLGN1 genes. PLoS One 7:e39277. 10.1371/journal.pone.0039277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calahorro F, Ruiz-Rubio M (2013) Human alpha- and beta-NRXN1 isoforms rescue behavioral impairments of Caenorhabditis elegans neurexin-deficient mutants. Genes Brain Behav 12:453–464. 10.1111/gbb.12046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culetto E, Baylis HA, Richmond JE, Jones AK, Fleming JT, Squire MD, Lewis JA, Sattelle DB (2004) The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-63 gene encodes a levamisole-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha subunit. J Biol Chem 279:42476–42483. 10.1074/jbc.M404370200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalva MB, McClelland AC, Kayser MS (2007) Cell adhesion molecules: signalling functions at the synapse. Nat Rev Neurosci 8:206–220. 10.1038/nrn2075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels SA, Ailion M, Thomas JH, Sengupta P (2000) egl-4 acts through a transforming growth factor-beta/SMAD pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans to regulate multiple neuronal circuits in response to sensory cues. Genetics 156:123–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz IP, Levin JZ, Cummins C, Anderson P, Horvitz HR (2003) sup-9, sup-10, and unc-93 may encode components of a two-pore K+ channel that coordinates muscle contraction in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci 23:9133–9145. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09133.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon C, Goda Y (2005) The actin cytoskeleton: integrating form and function at the synapse. Annu Rev Neurosci 28:25–55. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresbach T, Neeb A, Meyer G, Gundelfinger ED, Brose N (2004) Synaptic targeting of neuroligin is independent of neurexin and SAP90/PSD95 binding. Mol Cell Neurosci 27:227–235. 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimer S, Gottschalk A, Hengartner M, Horvitz HR, Richmond J, Schafer WR, Bessereau JL (2007) Regulation of nicotinic receptor trafficking by the transmembrane Golgi protein UNC-50. EMBO J 26:4313–4323. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JT, Squire MD, Barnes TM, Tornoe C, Matsuda K, Ahnn J, Fire A, Sulston JE, Barnard EA, Sattelle DB, Lewis JA (1997) Caenorhabditis elegans levamisole resistance genes lev-1, unc-29, and unc-38 encode functional nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits. J Neurosci 17:5843–5857. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05843.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis MM, Evans SP, Jensen M, Madsen DM, Mancuso J, Norman KR, Maricq AV (2005) The ror receptor tyrosine kinase CAM-1 is required for ACR-16-mediated synaptic transmission at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction. Neuron 46:581–594. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gally C, Eimer S, Richmond JE, Bessereau JL (2004) A transmembrane protein required for acetylcholine receptor clustering in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 431:578–582. 10.1038/nature02893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendrel M, Rapti G, Richmond JE, Bessereau JL (2009) A secreted complement-control-related protein ensures acetylcholine receptor clustering. Nature 461:992–996. 10.1038/nature08430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves A, Ambrósio AF, Fernandes R (2013) Regulation of claudins in blood-tissue barriers under physiological and pathological states. Tissue Barriers 1:e24782. 10.4161/tisb.24782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green WN. (1999) Ion channel assembly: creating structures that function. J Gen Physiol 113:163–170. 10.1085/jgp.113.2.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevi S, McKay J, Palfreyman M, Yassin L, Eshel M, Jorgensen E, Treinin M (2002) The C. elegans ric-3 gene is required for maturation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. EMBO J 21:1012–1020. 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamazaki Y, Itoh M, Sasaki H, Furuse M, Tsukita S (2002) Multi-PDZ domain protein 1 (MUPP1) is concentrated at tight junctions through its possible interaction with claudin-1 and junctional adhesion molecule. J Biol Chem 277:455–461. 10.1074/jbc.M109005200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada S, Hori I, Yamamoto H, Hosono R (1994) Mutations in the unc-41 gene cause elevation of acetylcholine levels. J Neurochem 63:439–446. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020439.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiskala M, Peterson PA, Yang Y (2001) The roles of claudin superfamily proteins in paracellular transport. Traffic 2:93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Hom S, Kudze T, Tong XJ, Choi S, Aramuni G, Zhang W, Kaplan JM (2012) Neurexin and neuroligin mediate retrograde synaptic inhibition in C. elegans. Science 337:980–984. 10.1126/science.1224896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie M, Hata Y, Takeuchi M, Ichtchenko K, Toyoda A, Hirao K, Takai Y, Rosahl TW, Südhof TC (1997) Binding of neuroligins to PSD-95. Science 277:1511–1515. 10.1126/science.277.5331.1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh M, Furuse M, Morita K, Kubota K, Saitou M, Tsukita S (1999) Direct binding of three tight junction-associated MAGUKs, ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3, with the COOH termini of claudins. J Cell Biol 147:1351–1363. 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M, Hoerndli FJ, Brockie PJ, Wang R, Johnson E, Maxfield D, Francis MM, Madsen DM, Maricq AV (2012) Wnt signaling regulates acetylcholine receptor translocation and synaptic plasticity in the adult nervous system. Cell 149:173–187. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jospin M, Qi YB, Stawicki TM, Boulin T, Schuske KR, Horvitz HR, Bessereau JL, Jorgensen EM, Jin Y (2009) Neuronal acetylcholine receptor regulates the balance of muscle excitation and inhibition in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol 7:e1000265. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MG, Campbell KP (2003) Gamma subunit of voltage-activated calcium channels. J Biol Chem 278:21315–21318. 10.1074/jbc.R300004200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SH, Taylor P (1999) Determinants responsible for assembly of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Gen Physiol 113:171–176. 10.1085/jgp.113.2.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Forrester WC (2003) Functional analysis of the domains of the C. elegans Ror receptor tyrosine kinase CAM-1. Dev Biol 264:376–390. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko OV, Yang XH, Hemler ME (2007) A novel cysteine cross-linking method reveals a direct association between claudin-1 and tetraspanin CD9. Mol Cell Proteomics 6:1855–1867. 10.1074/mcp.M700183-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladwein M, Pape UF, Schmidt DS, Schnölzer M, Fiedler S, Langbein L, Franke WW, Moldenhauer G, Zöller M (2005) The cell–cell adhesion molecule EpCAM interacts directly with the tight junction protein claudin-7. Exp Cell Res 309:345–357. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Wu CH, Berg H, Levine JH (1980) The genetics of levamisole resistance in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 95:905–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Li L, Wang W, Gong J, Yang X, Hu Z (2018) Spontaneous vesicle fusion is differentially regulated at cholinergic and GABAergic synapses. Cell Rep 22:2334–2345. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maro GS, Gao S, Olechwier AM, Hung WL, Liu M, Özkan E, Zhen M, Shen K (2015) MADD-4/Punctin and neurexin organize C. elegans GABAergic postsynapses through neuroligin. Neuron 86:1420–1432. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter K, Balda MS (2003) Holey barrier: claudins and the regulation of brain endothelial permeability. J Cell Biol 161:459–460. 10.1083/jcb.200304039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C, Fire A (1995) DNA transformation. Methods Cell Biol 48:451–482. 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)61399-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb D, Ambros V (1991) Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J 10:3959–3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KG, Alfonso A, Nguyen M, Crowell JA, Johnson CD, Rand JB (1996) A genetic selection for Caenorhabditis elegans synaptic transmission mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:12593–12598. 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris AD, Lundquist EA (2011) UNC-6/netrin and its receptors UNC-5 and UNC-40/DCC modulate growth cone protrusion in vivo in C. elegans. Development 138:4433–4442. 10.1242/dev.068841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurrish S, Ségalat L, Kaplan JM (1999) Serotonin inhibition of synaptic transmission: Galpha(0) decreases the abundance of UNC-13 at release sites. Neuron 24:231–242. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80835-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien BMJ, Palumbos SD, Novakovic M, Shang X, Sundararajan L, Miller DM 3rd (2017) Separate transcriptionally regulated pathways specify distinct classes of sister dendrites in a nociceptive neuron. Dev Biol 432:248–257. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey P, Bhardwaj A, Babu K (2017) Regulation of WNT signaling at the neuromuscular junction by the immunoglobulin superfamily protein RIG-3 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 206:1521–1534. 10.1534/genetics.116.195297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S, Binder DK, Manley GT, Krishna S, Verkman AS (2004) Molecular mechanisms of brain tumor edema. Neuroscience 129:1011–1020. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierron M, Pinan-Lucarré B, Bessereau JL (2016) Preventing illegitimate extrasynaptic acetylcholine receptor clustering requires the RSU-1 protein. J Neurosci 36:6525–6537. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3733-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinan-Lucarré B, Tu H, Pierron M, Cruceyra PI, Zhan H, Stigloher C, Richmond JE, Bessereau JL (2014) C. elegans punctin specifies cholinergic versus GABAergic identity of postsynaptic domains. Nature 511:466–470. 10.1038/nature13313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapti G, Richmond J, Bessereau JL (2011) A single immunoglobulin-domain protein required for clustering acetylcholine receptors in C. elegans. EMBO J 30:706–718. 10.1038/emboj.2010.355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard M, Boulin T, Robert VJ, Richmond JE, Bessereau JL (2013) Biosynthesis of ionotropic acetylcholine receptors requires the evolutionarily conserved ER membrane complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E1055–E1063. 10.1073/pnas.1216154110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JE. (2006) Electrophysiological recordings from the neuromuscular junction of C. elegans. WormBook 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JE, Jorgensen EM (1999) One GABA and two acetylcholine receptors function at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction. Nat Neurosci 2:791–797. 10.1038/12160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert V, Bessereau JL (2007) Targeted engineering of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome following Mos1-triggered chromosomal breaks. EMBO J 26:170–183. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein E. (2011) The complexity of tetraspanins. Biochem Soc Trans 39:501–505. 10.1042/BST0390501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW (2001) Molecular cloning: A Laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbour, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sawada N, Murata M, Kikuchi K, Osanai M, Tobioka H, Kojima T, Chiba H (2003) Tight junctions and human diseases. Med Electron Microsc 36:147–156. 10.1007/s00795-003-0219-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Kim E (2011) The postsynaptic organization of synapses. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3:a005678. 10.1101/cshperspect.a005678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Hoogenraad CC (2007) The postsynaptic architecture of excitatory synapses: a more quantitative view. Annu Rev Biochem 76:823–847. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060805.160029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth D, Ch'ng Q, Dybbs M, Tavazoie M, Kennedy S, Wang D, Dupuy D, Rual JF, Hill DE, Vidal M, Ruvkun G, Kaplan JM (2005) Systematic analysis of genes required for synapse structure and function. Nature 436:510–517. 10.1038/nature03809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DJ, Madison JM, Conery AL, Thompson-Peer KL, Soskis M, Ruvkun GB, Kaplan JM, Kim JK (2008) The microRNA miR-1 regulates a MEF-2-dependent retrograde signal at neuromuscular junctions. Cell 133:903–915. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simske JS, Hardin J (2011) Claudin family proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods Mol Biol 762:147–169. 10.1007/978-1-61779-185-7_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simske JS, Köppen M, Sims P, Hodgkin J, Yonkof A, Hardin J (2003) The cell junction protein VAB-9 regulates adhesion and epidermal morphology in C. elegans. Nat Cell Biol 5:619–625. 10.1038/ncb1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AB, Sharma A, Dhawan P (2010) Claudin family of proteins and cancer: an overview. J Oncol 2010:541957. 10.1155/2010/541957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ, O'Brien T, Chatzigeorgiou M, Spencer WC, Feingold-Link E, Husson SJ, Hori S, Mitani S, Gottschalk A, Schafer WR, Miller DM 3rd (2013) Sensory neuron fates are distinguished by a transcriptional switch that regulates dendrite branch stabilization. Neuron 79:266–280. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staab TA, Evgrafov O, Knowles JA, Sieburth D (2014) Regulation of synaptic nlg-1/neuroligin abundance by the skn-1/Nrf stress response pathway protects against oxidative stress. PLoS Genet 10:e1004100. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Kamata R, Sakai R (2005a) EphA2 phosphorylates the cytoplasmic tail of claudin-4 and mediates paracellular permeability. J Biol Chem 280:42375–42382. 10.1074/jbc.M503786200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Kamata R, Sakai R (2005b) Phosphorylation of ephrin-B1 via the interaction with claudin following cell–cell contact formation. EMBO J 24:3700–3711. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong XJ, López-Soto EJ, Li L, Liu H, Nedelcu D, Lipscombe D, Hu Z, Kaplan JM (2017) Retrograde synaptic inhibition is mediated by alpha-neurexin binding to the alpha2delta subunits of N-type calcium channels. Neuron 95:326–340.e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touroutine D, Fox RM, Von Stetina SE, Burdina A, Miller DM 3rd, Richmond JE (2005) acr-16 encodes an essential subunit of the levamisole-resistant nicotinic receptor at the Caenorhabditis elegans neuromuscular junction. J Biol Chem 280:27013–27021. 10.1074/jbc.M502818200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towers PR, Edwards B, Richmond JE, Sattelle DB (2005) The Caenorhabditis elegans lev-8 gene encodes a novel type of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha subunit. J Neurochem 93:1–9. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02951.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu H, Pinan-Lucarré B, Ji T, Jospin M, Bessereau JL (2015) C. elegans punctin clusters GABA(A) receptors via neuroligin binding and UNC-40/DCC recruitment. Neuron 86:1407–1419. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turksen K, Troy TC (2004) Barriers built on claudins. J Cell Sci 117:2435–2447. 10.1242/jcs.01235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM (2006) Claudins and epithelial paracellular transport. Annu Rev Physiol 68:403–429. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.131404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoven MK, Bauer Huang SL, Albin SD, Bargmann CI (2006) The claudin superfamily protein nsy-4 biases lateral signaling to generate left-right asymmetry in C. elegans olfactory neurons. Neuron 51:291–302. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashlishan AB, Madison JM, Dybbs M, Bai J, Sieburth D, Ch'ng Q, Tavazoie M, Kaplan JM (2008) An RNAi screen identifies genes that regulate GABA synapses. Neuron 58:346–361. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S (1976) The structure of the ventral nerve cord of Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 275:327–348. 10.1098/rstb.1976.0086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S (1986) The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 314:1–340. 10.1098/rstb.1986.0056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W, Dong X, Broederdorf TR, Shen A, Kramer DA, Shi R, Liang X, Miller DM 3rd, Xiang YK, Yasuda R, Chen B, Shen K (2018) A dendritic guidance receptor complex brings together distinct actin regulators to drive efficient F-actin assembly and branching. Dev Cell 45:362–375.e3. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]