Abstract

Background

Mutations in the X-linked gene filamin A (FLNA), encoding the actin-binding protein FLNA, cause a wide spectrum of connective tissue, skeletal, cardiovascular and/or gastrointestinal manifestations. Males are typically more severely affected than females with common pre- or perinatal death.

Case presentation

We provide a genotype- and phenotype-oriented literature overview of FLNA hemizygous mutations and report on two live-born male FLNA mutation carriers. Firstly, we identified a de novo, missense mutation (c.238C > G, p.(Leu80Val)) in a five-year old Indian boy who presented with periventricular nodular heterotopia, increased skin laxity, joint hypermobility, mitral valve prolapse with regurgitation and marked facial features (e.g. a flat face, orbital fullness, upslanting palpebral fissures and low-set ears). Secondly, we identified two cis-located FLNA mutations (c.7921C > G, p.(Pro2641Ala); c.7923delC, p.(Tyr2642Thrfs*63)) in a Bosnian patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome-like features such as skin translucency and joint hypermobility. This patient also presented with brain anomalies, pectus excavatum, mitral valve prolapse, pulmonary hypertension and dilatation of the pulmonary arteries. He died from heart failure in his second year of life.

Conclusions

These two new cases expand the list of live-born FLNA mutation-positive males with connective tissue disease from eight to ten, contributing to a better knowledge of the genetic and phenotypic spectrum of FLNA-related disease.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12881-018-0655-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Periventricular nodular heterotopia, Live-born males, Filaminopathy, Connective tissue disease

Background

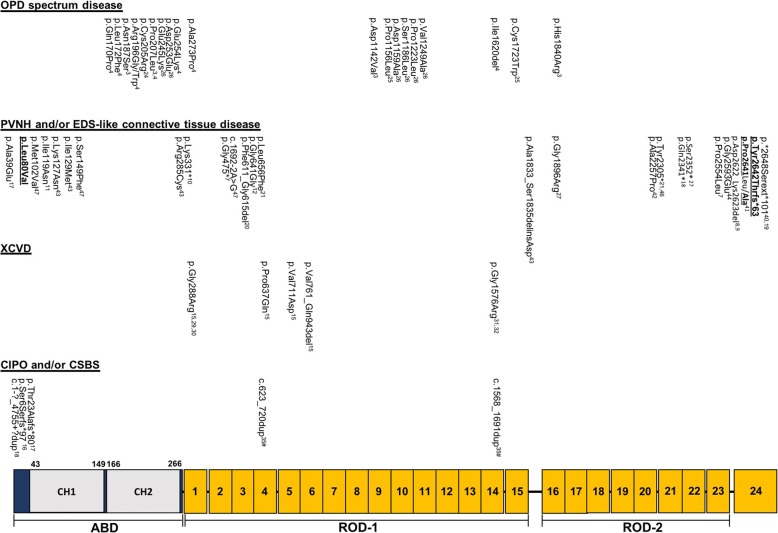

FLNA encodes a widely expressed 280-kD dimeric protein that crosslinks actin filaments into three-dimensional networks and attaches them to the cell membrane. Each monomeric chain of the protein consists of four major domains: a N-terminal F-Actin-Binding Domain (ABD) consisting of two tandem calponin homology domains (CH1 and CH2), two ROD regions which are composed of 23 Ig-like repeats, and a repeat at the C-terminus, undergoing dimerization prior to interaction with membrane receptors (Fig. 1) [1]. FLNA is involved in various cell functions, such as signal transduction, cell migration and adhesion [2] and FLNA mutations have been linked to a wide spectrum of disorders.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the FLNA domains and repeats and overview of FLNA mutations and their associated disorders. Each FLNA-related disorder and their causal mutations in live-born males is depicted separately. The four diseases indicate the primary clinical expression of the patients. Mutations in bold and underlined are identified within the current paper. Mutations indicated with # occur together in patients of the same family

Classification of these filaminopathies depends on the nature of the underlying mutation mechanism. Gain-of-function mutations cause otopalatodigital disorders (OPD) [3, 4], while loss-of-function mutations result in periventricular nodular heterotopia (PVNH) with or without connective tissue findings [5–14], X-linked cardiac valvular dystrophy (XCVD) [15], or gastrointestinal diseases such as chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO) and congenital short bowel syndrome (CSBS) [16–18]. Patients presenting phenotypical features of multiple FLNA-related diseases have been described as well [19, 20]. While in heterozygous females the FLNA-related phenotype ranges from absence of overall symptoms to severe manifestations, most male mutation carriers die prenatally or in the first years of life [21–23]. This points towards a key role for FLNA in human embryonic development. In the literature, 65 different FLNA mutations have been reported in live-born males (Fig. 1). Here, we report on two male cases with connective tissue disease and brain abnormalities who carry novel FLNA mutations. In addition as an introduction, we provide a literature overview on FLNA genetic variability in live-born males.

Literature overview

The OPD spectrum encompasses five X-linked disorders, in order of severity: OPD1, OPD2, frontometaphyseal dysplasia (FMD), Melnick-Needles syndrome (MNS), and terminal osseous dysplasia with/without pigmentary defects (TOD(PD)). These syndromes are predominantly characterized by skeletal dysplasia (i.e. bowing of long bones, limb deformation, and short stature), hearing loss, facial dysmorphism, cleft palate and abnormalities of the extremities. The central nervous system, cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal tract, ocular system, cutaneous system and respiratory airways are occasionally affected as well [4]. MNS or TOD(PD) male offspring of affected mothers die prenatally or shortly after birth [4]. OPD2 males die in their first year of life, mostly due to pulmonary hypertension caused by thoracic and lung hypoplasia [23, 24], while FMD exhibits a milder phenotype in affected males [25, 26]. OPD1 males survive to normal adulthood. OPD-causing mutations (missense mutations and small in-frame deletions) cluster in four specific domains, i.e. the ABD and filamin repeats 3, 10 and 14/15 (Fig. 1) [1, 4]. They act through a gain-of-function mechanism by establishing abnormal interactions between FLNA and its binding partners, such as membrane receptors, transcription factors and enzymes. No genotype-phenotype correlation has yet been described for the OPD subtypes.

PVNH is a neuronal migration disorder that can occur in FLNA males [21], but is more frequently observed in females. About 90% of PVNH patients present with difficult-to-treat seizures, manifesting from early childhood to adulthood [27]. It can occur with or without Ehlers-Danlos syndrome-like (EDS-like) connective tissue anomalies such as joint hypermobility, skin hyperelasticity, translucent skin and cardiovascular abnormalities. The condition is prenatally or neonatally lethal when caused by truncating FLNA mutations, such as N-terminal nonsense or out-of-frame splicing mutations [21]. In PVNH males who survive past infancy, distal truncating, hypomorphic missense or mosaic mutations are identified, implying that at least some functional FLNA is produced [19, 21].

XCVD is characterized by stenosis, regurgitation or prolapse of the mitral and/or aortic valve. Male XCVD cases with FLNA mutations typically display severe phenotypes such as polyvalvular disease, regularly requiring valve replacement surgery [28]. Although sudden cardiac death occasionally occurs during infancy, they tend to survive up to adulthood [15, 20, 28–30]. Brain imaging in a subset of cases did not reveal PVNH [28]. XCVD-causing FLNA mutations are mostly missense or splice-altering mutations affecting highly conserved amino acids in five of the protein’s first seven filamin repeats, i.e. repeats 1, 4, 5, 6 and 7 (Fig. 1) [15, 28–30]. Of note, two FLNA missense mutations (p.(Gly1554Arg) and p.(Gly1576Arg)) have most recently been linked to an X-linked syndrome of cardiac valvulopathy, but also keloid scarring, reduced joint mobility and a large optic cup-to-disc ratio [31–33]. In case of p.(Gly1554Arg), also Ebstein anomaly segregated with the mutation [33]. Further investigation is needed to determine these mutations’ precise mode of action. Besides in heart and brain, FLNA is highly expressed in neurons of the enteric system. As a consequence, intestinal abnormalities have recurrently been described in FLNA mutation-positive males (Table 1), but these usually do not present as primary symptoms. Few exceptions can be found in literature and those have been described as CIPO or CSBS (Fig. 1) [16, 17]. CIPO is characterized by severely impaired gastrointestinal motility owing to impaired involuntary or coordinated muscular contraction of the gastrointestinal tract. CSBS patients present with abdominal pain and diarrhea due to a shortened small intestine and intestinal malrotation. Initially, CIPO and CSBS mutations were identified between FLNA’s first two methionines. More recently, duplications of multiple FLNA repeats have also been described (Fig. 1) [16, 17, 34, 35].

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of male FLNA mutation-positive survivors with PVNH and/or EDS-like connective tissue disease

| Mutation (AA) | Age | Age of death | PVNH | Other neurological findings | Aortic dilatation | Other cardiac involvement | Skeletal findings | Skin findings | Gastro-intestinal involvement | Other | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | p.Ala39Glu | 37y | ND | Yes | Transient neonatal convulsions Mega cisterna magna |

No | MVP with mild MR TAV with mild AR |

No | No | ND | Bilateral epicanthic folds Telecanthus Anteverted nared Anteverted helices |

[11] |

| 2 | p.Leu80Val | 5y | ND | Yes | ND | No | MVP with MR TVP with TR |

Bilateral hip dislocation Joint hypermobility Brachydactyly Genu recurvatum |

Skin laxity Excess skin folds over the fingers |

ND | Low set, posteriorly rotated ears Telecanthus Epicanthal folds Periorbital fullness Infraorbital creases |

This report |

| 3 | p.Met102Val | 3y | ND | Yes | Cerebellar hypoplasia Mildly delayed milestones | No | PDA | ND | ND | ND | Cryptorchidism | [47] |

| 4 | p.Ile119Asn | ND | 57y | Yes | Mega cisterna magna | Yes (60 mm) | MVP with MR | ND | ND | ND | Thrombopenia | [11] |

| 5 | p.Lys127Asn | 15y | ND | Yes | Mega cisterna magna | Yes (31 mm) | Mild MVP Thick MV |

Joint hypermobility (8/9) Mild pectus carinatumScoliosis |

Soft, mildly hyperelastic skin Umbilical hernia | ND | ND | [43] |

| 6 | p.Ile129Met | 1d | ND | Yes | ND | No | Dysplastic MV and TV | ND | Skin laxity | ND | High arched palate | [43] |

| 7 | p.Ser149Phe | 38y | ND | Yes | Complex partial and generalized seizures | No | AR | ND | ND | ND | ND | [47] |

| 8 | p.Arg285Cys | 10y | ND | Yes | Seizures | No | MVP, small ASD | Joint hypermobility (6/9) | Thin,translucent, elastic skin Supraumbilical hernia | ND | High arched palate | [43] |

| 9 | p.Lys331* (mosaic) | 1d | ND | Yes | Cerebral vasculature dysplasia Corpus callosum hypoplasia |

No | PDA, VSD | ND | ND | Intestinal pseudo-obstruction (IPO) Malrotation Short gut syndrome with dilated small intestine |

Bifid uvula Persistent Thrombocytopenia |

[10] |

| 10 | p.Gly475* | 17y | ND | Yes | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | [7] |

| 11 | c.1692-2A > G (mosaic) | 49y | ND | Yes | Cerebellar hypoplasia Partial complex and generalized seizures |

Yes | AV replacement at 26y | Pes cavus | ND | ND | Bifid epiglottis | [47] |

| 12 | p.Phe611_Gly615del | 18y | 50y | ND* | Spinal osteo-arthritis Muscle hypotonia |

No | Severe polyvalvular heart dysplasia Dilatation of both atria Chronic heart failure |

Joint hypermobility (8/9) Scoliosis Genua valga, Bilateral varus deformity |

Soft and doughy skin Skin laxity Atrophic scar Prominent veins |

ND | Dysmorphic facial features | [20] |

| 13 | p.Gly641Gly | 1d | ND | Yes | ND | No | Septal defect PVP Dysplastic TV |

Talipes equinovarus | Inguinal hernia | Severe constipation Malrotation |

Hypertelorism Downslanting palpebral fissures Low set, posteriorly rotated ears |

[12] |

| 14 | p.Leu656Phe | ND | ND | Yes | Seizures | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | [21] |

| 15 | p.Ala1833_Ser1835delinsAsp | 1d | 2 m | Yes | Corpus callosum hypoplasia Cervical syringomyelia |

Yes | Dysplastic aorta, MV and TV ASD, small VSD, PDA Tortuous supra-aortic vessels Pulmonary hypertension with heart failure |

Joint hypermobility | Skin laxity | Malrotation (autopsy) | ND | [43] |

| 16 | p.Gly1896Arg (mosaic) | 57y | ND | Yes | Seizures Mega cisterna magna |

No | ND | ND | ND | ND | Progressive obstructive lung disease | [27] |

| 17a | p.Glu2142AlafsTer22 | 19y | ND | No | No | Yes | Severe MR with MVP Moderate AR Dilatation of the bilateral pulmonary arteries |

Pectus excavatum | Bilateral inguinal hernias Thin skin |

Intestinal malrotation CIPO Crohn’s disease |

Thrombocytopenia | [34] |

| 17b | 11y | ND | No | No | No | Moderate MR with MVP ASD |

No | Bilateral inguinal hernias | Intestinal malrotation CIPO |

Cryptorchidism | ||

| 18 | p.Ala2257Pro | 16y | ND | Yes | Moderate weakness and atropy of the intrinsic hand muscles and wrist extensors bilaterally Seizures | No | PDA AV dysfunction |

Joint hypermobility (7/9) Pectus excavatum Bilateral genu recurvatum |

Skin laxity | Malrotation Short gut syndrome |

ND | [42] |

| 19a | p.Tyr2305* | ND | ND | Yes | Seizures | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | [21, 46] |

| 19b | 36y | 36y | Yes | Seizures | Yes | AR Left ventricular hypertrophy Left atrial enlargement |

ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 20 | p.Gln2341* | Prenatally | 6w | Yes | Posterior fossa arachnoid cyst | ND | ND | Spina bifida occulta Proximally placed thumbs |

ND | Diaphragmatic defect Displaced stomach and spleen Short gut syndrome with dilated loops of small intestine |

“Square face”, flat philtrum Wide metopic suture High-arched palate |

[18] |

| 21 | p.Ser2352* (mosaic) | 38y | ND | Yes | Inward rotation of anterior ventricular horns Corpus callosum hypoplasia Mega cisterna magna |

ND | ND | Broad and flattened OPD I-like end phalanges of both feet | ND | ND | Retrognathia Hypertelorism Low-set ears |

[27] |

| 22 | p.Pro2554Leu | 56y | ND | Yes | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | [7] |

| 23 | p.Gly2593Glu | ND | ND | Yes | Seizures Migraines |

No | ND | Joint hypermobility Tall thin habitus | ND | ND | Left-sided sensorineural hearing loss Retinal lattice degeneration High arched palate |

[44] |

| 24a | p.Asp2622_Lys2623del | 5y | ND | Yes | Corpus callosum hypoplasia Mega cisterna magna |

ND | ND | Scoliosis Mild platyspondyly Spatulate finger tips Short, broad phalanges and metacarpus Skeletal dysplasia of the posterior fossa and frontal sinuses Delayed bone age |

ND | ND | Dysmorphic facial features | [8, 9] |

| 24b | Neonatal | ND | Yes | Corpus callosum hypoplasia Mega cisterna Magna |

ND | ND | Mild platyspondyly, Spatulate finger tips Short broad phalanges and metacarpus Skeletal dysplasia of the posterior fossa and frontal sinuses Delayed bone age |

ND | Malrotation | Dysmorphic facial features | ||

| 25 |

p.Pro2641Ala

p.Tyr2642ThrfsTer63 |

1d | 2y | ND* | Broad interhemispheric fissures and subarchnoid spaces with echogenic parenchyma Muscle hypoplasia and hypotonia |

No | Dysmorphic/elongated cusps TV with TVR Thinned/elongated cusps MV with MVP, ASD Dilated pulmonary arteries Pulmonary hypertension, leading to heart failure and early demise |

Joint hypermobility Pectus excavatum |

Translucent skin | Chronic diarrhea | Dysmorphic facial features Food allergies Recurrent bronchitis |

This report |

| 26a | p.Pro2641Leu | 1d | ND | Yes | Enlarged anterior fontanel Ventriculomegaly Seizures Mental retardation |

No | PDA | ND | ND | ND | Severe bronchodysplasia | [41] |

| 26b | 1d | 8 m | Yes | Enlarged anterior fontanel Ventriculomegaly Microgyria Microcephaly |

No | PDA | ND | ND | ND | Severe bronchodysplasia resulting in death | ||

| 27a | p.*2648Serext*101 | Neonatal | ND | Yes | Corpus callosum hypoplasia Retrocerebellar cyst |

No | PDA | ND | Inguinal hernia | Pyloric stenosis Constipation Malrotation Short gut syndrome |

Dysmorphic facial features | [40, 19] |

| 27b | Neonatal | ND | Yes | Mildly delayed motor development – hyptonia Retrocerebellar cyst |

No | Mildly dysplastic MV PDA |

Mild pectus excavatum | ND | Severe constipation Gastro-intestinal obstruction Short gut syndrome |

Recurrent upper respiratory tract infections Dysmorphic facial features |

||

| 27c | 1d | ND | Yes | Hypoplastic cerebellum and vermis | No | ASD | ND | ND | Short gut syndrome Malrotation | Dysmorphic facial features | ||

AR aortic regurgitation, ASD atrial septal defect, AV aortic valve, MVR: mitral valve regurgitation, MR mitral regurgitation, MV mitral valve, MVP mitral valve prolapse, ND not described, PDA patent ductus arteriosus, PVP pulmonary valve prolapse, TAV tricuspid aortic valve, TV tricuspid valve, TVP tricuspid valve prolapse, TVR tricuspid valve regurgitation, VSD ventricular septal defect, CIPO chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Patient 23a is brother of patient 23b

Case presentations

Proband with connective tissue findings carrying a de novo p.(Leu80Val) mutation

Clinical description

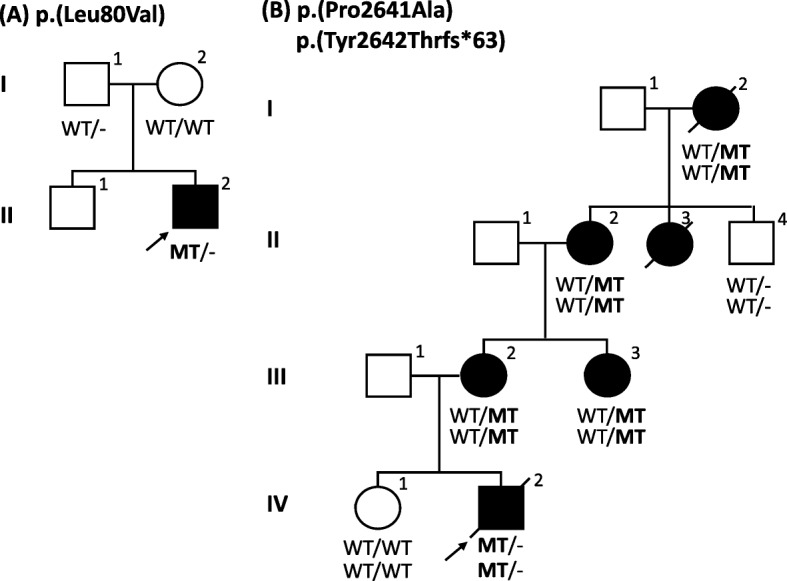

The proband is a five-year old Indian boy (II-2) without a family history of connective tissue or cardiovascular disease (Fig. 2a). He was born at 34 weeks of gestation to non-consanguineous parents by normal vaginal delivery with a birth weight of 2.4 kg. Bilateral hip dislocation and cryptorchidism were noted on the second day of life. A pavlik harness was applied during the first six months and he underwent bilateral varus derotation osteotomy for hip subluxation (Fig. 3e) at four years of age. Cryptorchidism was surgically treated at three years of age. At the age of five, his height was 98 cm (2 SD below the mean), head circumference was 49.5 cm (2 SD below the mean) and weight was 14 kg (2 SD below the mean). Craniofacial examination demonstrated brachycephaly, telecanthus with upslanting palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, periorbital fullness and infraorbital creases bilaterally and low-set, posteriorly rotated ears (Fig. 4a, b). Further clinical examination revealed marked skin laxity with excess skinfolds over the fingers (Fig. 4c, d, h, i and j). Increased mobility across all joints, and brachydactyly with proximally placed thumbs (Figures e,f), flat feet with sandal gap and medially deviated great toes were also observed (Fig. 4g). Radiographs revealed dislocated distal phalanx of the right thumb (Fig. 3c). The pelvis had narrow iliac bones and a wide femoral neck (Fig. 3d). The spine showed tall vertebral bodies (Fig. 3a, b, g). Motor development was mildly delayed, illustrated by the fact that he only started walking independently at 20 months of age. At age 5, he presented with genu recurvatum and bilateral hip subluxation for which he underwent bilateral varus derotation osteotomy (Fig. 3d, e, f). Cognitive and language milestones as well as his ophthalmological parameters were normal. Echocardiography revealed a myxomatous and prolapsed mitral valve with moderate regurgitation. Additionally, it also showed tricuspid aortic valve prolapse with mild regurgitation. Aortic measurements were within the normal range. After molecular diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed PVNH along the subependymal regions of both lateral ventricles (Fig. 3h, i; Additional file 1: Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Family pedigrees with their respective mutations. Squares represent males, circles represent females, black-filled symbols represent affected individuals and a + or − sign denotes the presence or absence of FLNA mutations. a Pedigree of case A, the Indian patient (proband) with a de novo FLNA missense mutation p.(Leu80Val) and his unaffected family members. b Pedigree of case B, the Bosnian patient with a frameshift p.(Tyr2642Thrfs*63) and a missense mutation p.(Pro2641Ala) in FLNA

Fig. 3.

Skeletal survey of five-year old Indian patient (case A). a, b, g At 5 years of age the skeletal survey revealed tall vertebral bodies, c delayed ossification of carpal bones, dislocated terminal phalanx of right thumb, d, e bilateral hip subluxation for which he underwent bilateral varus derotation osteotomy, f genu recurvatum and (h, i) magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed PVNH along the subependymal regions of both lateral ventricles

Fig. 4.

Clinical features. In the five-year old Indian patient (case A) the following features were noted: (a) flat face, telecanthus, orbital fullness, upslant of palpebral fissures, prominent nasolabial folds, (b) brachycephaly, midface retrusion and low-set ears, (e, f) mild brachydactyly and a deformed right thumb due to an unstable and lax interphalangeal joint, (g) broad and medially deviated great toes with sandal gap and flat feet and (c, d, h, i, j) extra skin folds and significant skin laxity. The proband of family B presented with (k, l) hypertelorism, pectus excavatum, clubfeet and hypermobile joints whereas the mother (III-2) demonstrated hypertelorism and joint hypermobility (m, n)

Molecular diagnosis

After obtaining informed consent of the parents, genomic DNA of the proband (III-2) was screened for mutations in 37 connective tissue disease genes (Division of Medical Genetics, Charité, Berlin), including the known genes for cutis laxa. No pathogenic variants were identified. Whole exome sequencing of III-2 was performed, which led to the identification of a novel missense mutation (c.238C > G, p.(Leu80Val)) in FLNA. Genotyping of p.(Leu80Val) in the proband’s parents revealed that the mutation arose de novo. In silico analysis strongly supports variant pathogenicity: (1) the variant is absent in the gnomAD database (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/; including 1000 Genomes database and the ExAC database) [36, 37] and also absent from the dbSNP database (build 147) [38] (2) p.(Leu80) is highly evolutionary conserved (down to zebrafish) and locates to the protein’s F-actin-binding domain, and (3) prediction programs SIFT, PolyPhen2 and MutationTaster predict a damaging effect on protein structure and/or function.

An EDS-like patient with two mutations in cis: a frameshift p.(Tyr2642Thrfs*63) and a missense mutation p.(Pro2641Ala)

Clinical description

The second patient is a male Bosnian infant with a positive family history for connective tissue and cardiovascular disease (Fig. 2b). He was born at 37 weeks of gestation by Caesarean section for placenta previa after an uneventful pregnancy. Immediately after birth he received oxygen support because of an underdeveloped left lung. Neonatal jaundice was treated with phototherapy. In the second week of life he was hospitalized again because of bacterial sepsis. The proband displayed dysmorphic features, such as hypertelorism, pectus excavatum, clubfeet and features of connective tissue disease, such as translucent skin, bilateral inguinal hernia and hypermobile joints (Fig. 4k, l). His neurological examination was significant for muscle hypotonia and poor muscle mass. Other health issues included hydro-ureteronephrosis, hypospadias, food allergies, chronic diarrhea (which improved with a modified diet) and recurrent bronchitis. Echocardiographic examination showed elongated cusps of the tricuspid valve with regurgitation, thinned and elongated cusps of the mitral valve with mitral valve prolapse, dilation of the pulmonary arteries with pulmonary hypertension and atrial septum defect with right atrial and ventricular dilatation. Aortic measurements at 12 months of age were normal. Brain ultrasound showed broader interhemispheric fissures and subarachnoid spaces with echogenic parenchyma. Since only ultrasound evaluation of the brain was available of the patient, no solid conclusion can be made about the presence or absence of PVNH. He died due to severe pulmonary hypertension and heart failure in his second year of life.

Family history revealed significant clinical findings in several female members (Fig. 2b). The mother (III-2) (Fig. 4m, n) presented with joint hypermobility and mild skin hyperelasticity. Her cerebral computed tomography (CT) and MRI-scan revealed cerebral atrophy, subependymal nodular heterotopia in the wall of the lateral ventricles and right frontal horn and intracranial hyperostosis of the frontal bones. Echocardiography of the mother (III-2) showed insufficiency of the aortic and pulmonary valves at age 33 years (both grade I-II). Hypermobile joints in the maternal aunt (III-3) and grandmother (II-2) were also noted. His great-aunt (II-3) had joint hypermobility, thin and soft skin and mild aortic valve regurgitation (diagnosed at age 9, but stable). She developed epilepsy with partial seizures from age 22. A brain MRI showed partial agenesis of the corpus callosum, cerebellar hypoplasia and PVNH. She died at the age of 48 due to an accident, which was a consequence of a seizure. The great-grandmother (I-2) was described as a frail person who died at age 82 years with renal insufficiency and heart failure (Additional file 2: Table S2).

Molecular diagnosis

Based on the patient’s phenotype, a Marfan syndrome (MFS) diagnosis was initially suspected. Mutation analysis, including multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) of FBN1 revealed no pathogenic variants. Further genetic investigation involved mutation analysis of the coding sequences of 22 genes [39] known to be implicated in the etiology of cardiovascular disease using gene panel sequencing. Two hemizygous cis variants in exon 48 of FLNA were identified and, subsequently, validated with Sanger sequencing: a frameshift c.7923delC; p.(Tyr2642Thrfs*63) and a missense c.7921C > G; p.(Pro2641Ala) mutation. For both mutations, several lines of evidence suggest involvement in disease development. Pathogenicity of p.(Tyr2642Thrfs*63) is supported by: (1) its absence from the gnomAD database (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/; including 1000 Genomes database and the ExAC database) [36, 37] and also absent from the dbSNP database (build 147) [38], (2) the fact that the mutation leads to the formation of an alternative stopcodon approximately 57 amino acids downstream of the original one, resulting in an aberrant protein C-terminus (i.e. a ‘no-stop mutation’), and (3) proven pathogenicity of a previously reported frameshift mutation with a similar effect at the protein level (p.(*2648Serext*101)), leading to systemic anomalies, including CIPO, PVNH, pyloric stenosis, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and atrial septum defect (ASD) [19, 40]. Evidence for pathogenicity of p.(Pro2641Ala) includes: (1) its absence from the gnomAD database (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/; including 1000 Genomes database and the ExAC database) [36, 37] and absent from the dbSNP database (build 147) [38], (2) p.(Pro2641) is highly conserved (up to Tetraodon) and locates to the C-terminal part of the protein, which is important for FLNA dimerization, (3) causality of another amino acid substitution at the same position (c.7922C > T; p.(Pro2641Leu)), causing PVNH, PDA, severe bronchodysplasia and partial seizures [41] and (4) classification of the variant as disease causing by prediction programs PolyPhen2, SIFT and MutationTaster.

After obtaining informed consent of the family members, segregation analysis of p.(Tyr2642Thrfs*63) and p.(Pro2641Ala) was performed, revealing the presence of both mutations in the patient’s clinically affected mother (III-2), maternal aunt (III-3), maternal grandmother (II-2) and maternal great-grandmother (I-2), further demonstrating pathogenicity of the mutations. His unaffected sister (IV-1) and brother of his grandmother (II-4) were mutation-negative.

Discussion and conclusions

About 30 male FLNA mutation-positive patients with PVNH have been reported, of which only six (patients 5, 6, 8, 12, 15, 18; Table 1) display both PVNH and EDS-like features (Table 1) [42–46]. Four of the latter were reported to present with cardiovascular anomalies, including aortic dilatation, mitral valve prolapse (MVP) and a dysplastic aortic, mitral or tricuspid valve [43, 45]. Joint hypermobility (5/6), skin translucency and/or hyperelasticity (5/6) were also common, while scoliosis and partial seizures were only noted once (Table 1) [42–44]. Null mutations typically lead to embryonic or early lethal PVNH in males. So far, the rare live-born males with PVNH or PVNH with EDS-like features were diagnosed with hypomorphic missense and distal truncating mutations, providing a sufficient amount of functional FLNA protein [43, 45]. Here, we report on a five-year old Indian boy who presents with connective tissue findings, attributed to a de novo FLNA mutation (p.(Leu80Val)) that locates to the CH1 domain. The initial presentation included skin laxity, joint hypermobility and prolapse of the mitral and tricuspid valve with moderate regurgitation. Additionally, motor development was mildly delayed and the skeletal system was prominently affected. After molecular diagnosis, brain imaging confirmed the presence of PVNH.

Untill this report, five live-born unrelated male cases had been described who were molecularly confirmed to carry missense mutations in the CH1 domain (amino acid 43–149) [43, 47, 48] (Fig. 1). Two unrelated males with FLNA mutations in CH1 have been described by Guerrini and colleagues [47]. The first male (p.(Met102Val)) was diagnosed with PVNH and cerebellar hypoplasia without seizures (patient 3, Table 1), while the other (p.(Ser149Phe)) had infrequent complex partial and secondarily generalized seizures (patient 7, Table 1). In both patients cardiovascular abnormalities were observed, including PDA and aortic valve insufficiency [47]. However, in contrast to our patient no connective tissue anomalies were observed. A p.(Glu82Val) mutation was previously described in a family with three affected females in two generations and five presumably affected boys whom all died within the first days or months of life. However, molecular confirmation could not be obtained for the male patients due to lack of DNA [48]. Reinstein et al. identified two unrelated PVNH males with EDS-like connective tissue manifestations who carried CH1-located FLNA mutations. A p.(Lys127Asn) mutation was found in a 15-year old male who had, besides PVNH without seizures, cardiovascular abnormalities (MVP with thickened mitral valve leaflets and dilatation of the sinuses of Valsalva), soft and hyperextensible skin, joint hypermobility, umbilical hernia, mild lumbar scoliosis and a spontaneous pneumothorax (patient 5, Table 1). A second male with a nearby-located FLNA mutation, p.(Ile129Met), presented with highly similar features, including PVNH without seizures, increased mobility across the joints, skin laxity and right inguinal hernia (patient 6, Table 1). From a cardiovascular point of view, however, he was more severely affected. He had dysplastic mitral and tricuspid valves with regurgitation, requiring mitral and tricuspid valvuloplasty at 10 months of age. He also developed recurrent pulmonary infections and at the age of one he was still hypotonic and had to be fed via a nasogastric tube (Table 1) [43]. The mutations identified by Reinstein and colleagues are located within a conserved hydrophobic region between amino acids 121–147 (Fig. 1). It is predicted that mutations within this motif have a direct effect on the actin binding of FLNA. In contrast, our mutation (affecting AA 80) is located upstream of this motif and is predicted to have an indirect effect on the actin binding capacity of the ABD [49]. This might explain the difference observed in facial and skeletal phenotype between our patient and those described by Reinstein et al. (2013).

The second case we reported is a male Bosnian patient, who carried a no-stop mutation (p.(Tyr2642Thrfs*63)) and a missense mutation (p.(Pro2641Ala)). He presented with skin and joint connective tissue findings. PVNH status is unknown as no MRI was performed. Cardiovascular anomalies included dilatation of both pulmonary arteries with pulmonary hypertension and heart failure of which he died at two years of age.

Two reports on affected males (patient 27 a,b,c; Table 1) describe a no-stop frameshift mutation (p.(*2648Serext*101)) that is highly similar to ours (Fig. 1) [19, 40]. This mutation affects the last amino acid of FLNA and is predicted to create a novel stop codon in the 3’ UTR polyadenylation signal. Besides PVNH, described male cases had prominent facial features (a low nasal bridge, broad mouth and a prominent forehead) and/or gastrointestinal problems (obstruction, intestinal malrotation and/or a short small bowel). Cardiovascular anomalies were also observed, including PDA, ASD and dysplastic mitral valves. These characteristics correspond with what is seen in our case B patient. Mildly delayed motor development was noted once. Remarkably, none presented with features reminiscent of EDS [19 and personal communication], which clearly differs from our case (case B) (Table 1).

Pulmonary artery dilation has not been commonly described in male FLNA mutation carriers. Only two other cases have been reported. Reinstein and colleagues examined a male FLNA mutation carrier (p.(Ala1833_Ser1835delinsAsp)), who presented with PVNH and pulmonary hypertension with heart failure (patient 15, Table 1). He had marked joint laxity and increased skin elasticity [43]. Another report mentioned two brothers with a 4-bp deletion (c.6425_6428delAGAG; p.(Glu2142Alafs*22)) in exon 40 of FLNA, predicted to cause a premature protein truncation (patients 17a and 17b, Table 1; Fig. 1). RT-PCR experiments on cDNA of the siblings suggested that the FLNA mutation induced both normal and alternative splicing. Both brothers had cardiac complications, with the oldest brother presenting with dilatation of the ascending aorta and bilateral pulmonary arteries. Bilateral inguinal hernias were noted in both brothers, while pectus excavatum only presented in the oldest one [34]. Those reports together with the findings in our case B indicate that pulmonary hypertension and/or dilatation are part of the phenotypic spectrum of FLNA-related disorders in males (Table 1).

In summary, FLNA can either exert loss-of-function or gain-of-function mechanisms, leading to clinically distinct disorders. Disease is typically more severe in male mutation carriers when compared to their female counterparts. Whereas most mutation-positive males die prenatally, a literature search demonstrates that a subset of them, i.e. those with hypomorphic missense, distal truncating or mosaic FLNA mutations, are live-born. Of these, eight (patients 5, 6, 8, 12, 15, 17a, 17b,18; Table 1) have been reported to present with EDS-like connective tissue disease. The two new cases (patients 2 and 25) reported here contribute to the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of EDS-like connective tissue disease, expanding the list of live-born males with FLNA mutations.

Additional files

Table S1. Clinical Timeline Case A. (DOCX 16 kb)

Table S1. Clinical Timeline Case B. (DOCX 14 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank the families for their participation in the study.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the University of Antwerp (Lanceringsproject 25777), the Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders (FWO, Belgium) [G.0221.12; G.0356.17], The Dutch Heart Foundation (2013 T093 BAV) and the Foundation Leducq (MIBAVA – Leducq 12CVD03). Bart Loeys is senior clinical investigator of the Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders (FWO, Belgium); and holds a starting grant from the European Research Council (ERC- StG-2012-30972-BRAVE). Aline Verstraeten is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship of the Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders (FWO, Belgium).

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that they incorporated all relevant clinical and genetic data in the article.

Abbreviations

- ABD

F-Actin-Binding Domain

- ASD

Atrial septum defect

- CH

Calponin homology

- CIPO

Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction

- CSBS

Congenital short bowel syndrome

- CT

Computed tomography

- EDS-like

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome-like

- FLNA

Filamin A

- FMD

Frontometaphyseal dysplasia

- MFS

Marfan syndrome

- MLPA

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

- MNS

Melnick-Needles syndrome

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MVP

Mitral valve prolapse

- OPD

Otopalatodigital disorders

- PDA

Patent ductus arteriosus patent ductus arteriosus

- PVNH

Periventricular nodular heterotopia

- TOD(PD)

Terminal osseous dysplasia with/without pigmentary defects

- XCVD

X-linked cardiac valvular dystrophy

Authors’ contributions

EC, AS, MH, LVL, BL, AV: made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. EC, AS, MH, MA, DS, LVL, KMG, IH, BL and AV have been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Antwerp University Hospital Ethics Committee (registration number B300201110784).

The authors declare that written consent for publication of the patients’ images has been obtained. All participants gave informed consent for this research.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Elyssa Cannaerts, Email: Elyssa.cannaerts@uantwerpen.be.

Anju Shukla, Email: dranju2003@yahoo.co.in.

Mensuda Hasanhodzic, Email: hmensuda@gmail.com.

Maaike Alaerts, Email: Maaike.alaerts@uantwerpen.be.

Dorien Schepers, Email: Dorien.schepers@uantwerpen.be.

Lut Van Laer, Email: Lut.vanlaer@uantwerpen.be.

Katta M. Girisha, Email: girishkatta@gmail.com

Iva Hojsak, Email: ivahojsak@gmail.com.

Bart Loeys, Email: Bart.loeys@uantwerpen.be.

Aline Verstraeten, Phone: +32 3 275 97 74, Email: Aline.verstraeten@uantwerpen.be.

References

- 1.Nakamura F, Osborn TM, Hartemink CA, Hartwig JH, Stossel TP. Structural basis of filamin a functions. J Cell Biol. 2007;179(5):1011–1025. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maestrini E, Patrosso C, Mancini M, Rivella S, Rocchi M, Repetto M, Villa A, Frattini A, Zoppe M, Vezzoni P, et al. Mapping of two genes encoding isoforms of the actin binding protein ABP-280, a dystrophin like protein, to Xq28 and to chromosome 7. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2(6):761–766. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moutton S, Fergelot P, Naudion S, Cordier MP, Sole G, Guerineau E, Hubert C, Rooryck C, Vuillaume ML, Houcinat N, et al. Otopalatodigital spectrum disorders: refinement of the phenotypic and mutational spectrum. J Hum Genet. 2016;61(8):693–699. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson SP, Twigg SR, Sutherland-Smith AJ, Biancalana V, Gorlin RJ, Horn D, Kenwrick SJ, Kim CA, Morava E, Newbury-Ecob R, et al. Localized mutations in the gene encoding the cytoskeletal protein filamin a cause diverse malformations in humans. Nat Genet. 2003;33(4):487–491. doi: 10.1038/ng1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheen VL, Jansen A, Chen MH, Parrini E, Morgan T, Ravenscroft R, Ganesh V, Underwood T, Wiley J, Leventer R, et al. Filamin a mutations cause periventricular heterotopia with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Neurology. 2005;64(2):254–262. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149512.79621.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox JW, Lamperti ED, Eksioglu YZ, Hong SE, Feng Y, Graham DA, Scheffer IE, Dobyns WB, Hirsch BA, Radtke RA, et al. Mutations in filamin 1 prevent migration of cerebral cortical neurons in human periventricular heterotopia. Neuron. 1998;21(6):1315–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80651-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu W, Yan B, An D, Xiao J, Hu F, Zhou D. Sporadic periventricular nodular heterotopia: classification, phenotype and correlation with Filamin a mutations. Epilepsy Res. 2017;133:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrera-Garcia L, Rivas-Crespo MF, Fernandez Garcia MS. Androgen receptor dysfunction as a prevalent manifestation in young male carriers of a FLNA gene mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(6):1710–1713. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parrini E, Rivas IL, Toral JF, Pucatti D, Giglio S, Mei D, Guerrini R. In-frame deletion in FLNA causing familial periventricular heterotopia with skeletal dysplasia in males. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(5):1140–1146. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masurel-Paulet A, Haan E, Thompson EM, Goizet C, Thauvin-Robinet C, Tai A, Kennedy D, Smith G, Khong TY, Sole G, et al. Lung disease associated with periventricular nodular heterotopia and an FLNA mutation. Eur J Med Genet. 2011;54(1):25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fergelot P, Coupry I, Rooryck C, Deforges J, Maurat E, Sole G, Boute O, Dieux-Coeslier A, David A, Marchal C, et al. Atypical male and female presentations of FLNA-related periventricular nodular heterotopia. Eur J Med Genet. 2012;55(5):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hehr U, Hehr A, Uyanik G, Phelan E, Winkler J, Reardon W. A filamin a splice mutation resulting in a syndrome of facial dysmorphism, periventricular nodular heterotopia, and severe constipation reminiscent of cerebro-fronto-facial syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43(6):541–544. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.038505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Wit MC, Kros JM, Halley DJ, de Coo IF, Verdijk R, Jacobs BC, Mancini GM. Filamin a mutation, a common cause for periventricular heterotopia, aneurysms and cardiac defects. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(4):426–428. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.149419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Wit MC, de Coo IF, Lequin MH, Halley DJ, Roos-Hesselink JW, Mancini GM. Combined cardiological and neurological abnormalities due to filamin a gene mutation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100(1):45–50. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0206-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kyndt F, Gueffet JP, Probst V, Jaafar P, Legendre A, Le Bouffant F, Toquet C, Roy E, McGregor L, Lynch SA, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding filamin a as a cause for familial cardiac valvular dystrophy. Circulation. 2007;115(1):40–49. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.622621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Werf CS, Sribudiani Y, Verheij JB, Carroll M, O'Loughlin E, Chen CH, Brooks AS, Liszewski MK, Atkinson JP, Hofstra RM. Congenital short bowel syndrome as the presenting symptom in male patients with FLNA mutations. Genet Med. 2013;15(4):310–313. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gargiulo A, Auricchio R, Barone MV, Cotugno G, Reardon W, Milla PJ, Ballabio A, Ciccodicola A, Auricchio A. Filamin a is mutated in X-linked chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction with central nervous system involvement. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(4):751–758. doi: 10.1086/513321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapur RP, Robertson SP, Hannibal MC, Finn LS, Morgan T, van Kogelenberg M, Loren DJ. Diffuse abnormal layering of small intestinal smooth muscle is present in patients with FLNA mutations and x-linked intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(10):1528–1543. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f0ae47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oegema R, Hulst JM, Theuns-Valks SD, van Unen LM, Schot R, Mancini GM, Schipper ME, de Wit MC, Sibbles BJ, de Coo IF, et al. Novel no-stop FLNA mutation causes multi-organ involvement in males. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A(9):2376–2384. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritelli M, Morlino S, Giacopuzzi E, Carini G, Cinquina V, Chiarelli N, Majore S, Colombi M, Castori M. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome with lethal cardiac valvular dystrophy in males carrying a novel splice mutation in FLNA. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(1):169–176. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheen VL, Dixon PH, KapurFox JW, Hong SE, Kinton L, Sisodiya SM, Duncan JS, Dubeau F, Scheffer IE, Schachter SC, et al. Mutations in the X-linked filamin 1 gene cause periventricular nodular heterotopia in males as well as in females. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(17):1775–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Hidalgo-Bravo A, Pompa-Mera EN, Kofman-Alfaro S, Gonzalez-Bonilla CR, Zenteno JC. A novel filamin a D203Y mutation in a female patient with otopalatodigital type 1 syndrome and extremely skewed X chromosome inactivation. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;136(2):190–193. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson S, et al. Otopalatodigital Spectrum Disorders. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, LJH B, Bird TD, Fong CT, Mefford HC, RJH S, editors. GeneReviews(R). Seattle: University of Washington; 1993-2018. ISSN: 2372-0697. [PubMed]

- 24.Sankararaman S, Kurepa D, Shen Y, Kakkilaya V, Ursin S, Chen H. Otopalatodigital syndrome type 2 in a male infant: a case report with a novel sequence variation. J Pediatr Genet. 2013;2(1):33–36. doi: 10.3233/PGE-13045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fennell N, Foulds N, Johnson DS, Wilson LC, Wyatt M, Robertson SP, Johnson D, Wall SA, Wilkie AO. Association of mutations in FLNA with craniosynostosis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(12):1684–1688. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robertson SP, Jenkins ZA, Morgan T, Ades L, Aftimos S, Boute O, Fiskerstrand T, Garcia-Minaur S, Grix A, Green A, et al. Frontometaphyseal dysplasia: mutations in FLNA and phenotypic diversity. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140(16):1726–1736. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lange M, Kasper B, Bohring A, Rutsch F, Kluger G, Hoffjan S, Spranger S, Behnecke A, Ferbert A, Hahn A, et al. 47 patients with FLNA associated periventricular nodular heterotopia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:134. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0331-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Tourneau T, Le Scouarnec S, Cueff C, Bernstein D, Aalberts JJJ, Lecointe S, Merot J, Bernstein JA, Oomen T, Dina C, et al. New insights into mitral valve dystrophy: a Filamin-a genotype-phenotype and outcome study. Eur Heart J. 2017;39(15):1269–1277. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aalberts JJ, van Tintelen JP, Oomen T, Bergman JE, Halley DJ, Jongbloed JD, Suurmeijer AJ, van den Berg MP. Screening of TGFBR1, TGFBR2, and FLNA in familial mitral valve prolapse. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(1):113–119. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernstein JA, Bernstein D, Hehr U, Hudgins L. Familial cardiac valvulopathy due to filamin a mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(9):2236–2241. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atwal PS, Blease S, Braxton A, Graves J, He W, Person R, Slattery L, Bernstein JA, Hudgins L. Novel X-linked syndrome of cardiac valvulopathy, keloid scarring, and reduced joint mobility due to filamin a substitution G1576R. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A(4):891–895. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lah M, Niranjan T, Srikanth S, Holloway L, Schwartz CE, Wang T, Weaver DD. A distinct X-linked syndrome involving joint contractures, keloids, large optic cup-to-disc ratio, and renal stones results from a filamin a (FLNA) mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A(4):881–890. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mercer CL, Andreoletti G, Carroll A, Salmon AP, Temple IK, Ennis S. Familial Ebstein Anomaly: Whole Exome Sequencing Identifies Novel Phenotype Associated With FLNA. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017;10(6):e001683. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oda H, Sato T, Kunishima S, Nakagawa K, Izawa K, Hiejima E, Kawai T, Yasumi T, Doi H, Katamura K, et al. Exon skipping causes atypical phenotypes associated with a loss-of-function mutation in FLNA by restoring its protein function. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24(3):408–414. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clayton-Smith J, Walters S, Hobson E, Burkitt-Wright E, Smith R, Toutain A, Amiel J, Lyonnet S, Mansour S, Fitzpatrick D, et al. Xq28 duplication presenting with intestinal and bladder dysfunction and a distinctive facial appearance. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(4):434–443. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Genomes Project C. Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO, Marchini JL, McCarthy S, McVean GA, et al. a global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, O'Donnell-Luria AH, Ware JS, Hill AJ, Cummings BB, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536(7616):285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM, Sirotkin K. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(1):308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Proost D, Vandeweyer G, Meester JA, Salemink S, Kempers M, Ingram C, Peeters N, Saenen J, Vrints C, Lacro RV, et al. Performant mutation identification using targeted next-generation sequencing of 14 thoracic aortic aneurysm genes. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(8):808–814. doi: 10.1002/humu.22802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berrou E, Adam F, Lebret M, Planche V, Fergelot P, Issertial O, Coupry I, Bordet JC, Nurden P, Bonneau D, et al. Gain-of-function mutation in Filamin a potentiates platelet integrin alphaIIbbeta3 activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(6):1087–1097. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerard-Blanluet M, Sheen V, Machinis K, Neal J, Apse K, Danan C, Sinico M, Brugieres P, Mage K, Ratsimbazafy L, et al. Bilateral periventricular heterotopias in an X-linked dominant transmission in a family with two affected males. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140(10):1041–1046. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hommel AL, Jewett T, Mortenson M, Caress JB. Juvenile muscular atrophy of the distal upper extremities associated with x-linked periventricular heterotopia with features of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2016;54(4):794–797. doi: 10.1002/mus.25175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinstein E, Frentz S, Morgan T, Garcia-Minaur S, Leventer RJ, McGillivray G, Pariani M, van der Steen A, Pope M, Holder-Espinasse M, et al. Vascular and connective tissue anomalies associated with X-linked periventricular heterotopia due to mutations in Filamin a. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(5):494–502. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Kogelenberg M, Clark AR, Jenkins Z, Morgan T, Anandan A, Sawyer GM, Edwards M, Dudding T, Homfray T, Castle B, et al. Diverse phenotypic consequences of mutations affecting the C-terminus of FLNA. J Mol Med (Berl) 2015;93(7):773–782. doi: 10.1007/s00109-015-1261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sole G, Coupry I, Rooryck C, Guerineau E, Martins F, Deves S, Hubert C, Souakri N, Boute O, Marchal C, et al. Bilateral periventricular nodular heterotopia in France: frequency of mutations in FLNA, phenotypic heterogeneity and spectrum of mutations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(12):1394–1398. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.162263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen MH, Choudhury S, Hirata M, Khalsa S, Chang B, Walsh CA. Thoracic aortic aneurysm in patients with loss of function Filamin a mutations: clinical characterization, genetics, and recommendations. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176(2):337–350. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guerrini R, Mei D, Sisodiya S, Sicca F, Harding B, Takahashi Y, Dorn T, Yoshida A, Campistol J, Kramer G, et al. Germline and mosaic mutations of FLN1 in men with periventricular heterotopia. Neurology. 2004;63(1):51–56. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000132818.84827.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moro F, Carrozzo R, Veggiotti P, Tortorella G, Toniolo D, Volzone A, Guerrini R. Familial periventricular heterotopia: missense and distal truncating mutations of the FLN1 gene. Neurology. 2002;58(6):916–921. doi: 10.1212/WNL.58.6.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruskamo S, Ylanne J. Structure of the human filamin a actin-binding domain. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65(11):1217–1221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909037330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Clinical Timeline Case A. (DOCX 16 kb)

Table S1. Clinical Timeline Case B. (DOCX 14 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that they incorporated all relevant clinical and genetic data in the article.