Abstract

Organic halogens are of great environmental and climatic concern. In this work, we have compiled their gas phase diffusivities (pressure-normalized diffusion coefficients) in a variety of bath gases experimentally measured by previous studies. It is found that diffusivities estimated using Fuller's semi-empirical method agree very well with measured values for organic halogens. In addition, we find that at a given temperature and pressure, different molecules exhibit very similar mean free paths in the same bath gas, and then propose a method to estimate mean free paths in different bath gases. For example, the pressure-normalized mean free paths are estimated to be 90, 350, 90, 80, 120 nm atm in air (and N2/O2), He, argon, CO2 and CH4, respectively, with estimated errors of around ±25%. A generic method, which requires less input parameter than Fuller's method, is proposed to calculate gas phase diffusivities. We find that gas phase diffusivities in He (and air as well) calculated using our method show fairly good agreement with those measured experimentally and estimated using Fuller's method. Our method is particularly useful for the estimation of gas phase diffusivities when the trace gas contains atoms whose diffusion volumes are not known.

Keywords: organic halogens, gas phase diffusion, mean free path

1. Introduction

Gas–surface interactions play important roles in many aspects of atmospheric chemistry and physics, including heterogeneous and multiphase reactions of atmospheric aerosol particles, cloud and rain droplets, and ice particles [1–4]. Atmosphere–ocean and atmosphere–land exchanges of gas molecules, such as dry deposition of trace gases, can also be considered as gas–surface interactions [5–7]. Recently, interactions with surfaces of human-made structures have been proposed as potentially important sources/sinks for several reactive trace gases [8–11]. The importance of gas–surface interactions has also been widely recognized in other fundamental and applied research areas, such as heterogeneous catalysis [12–14].

Gas–surface interactions typically consist of coupled physical and chemical processes in and between different phases [15–17]. Diffusion of gas molecules towards the surface is the first step for their uptake by the surface [16], and vice versa it is the final step for the release of gas molecules from the surface. The rate of gas phase diffusion depends on the concentration gradient and the gas phase diffusion coefficient [18], and thus knowledge of gas phase diffusion coefficients is critical for understanding gas–surface interactions. However, until recently not much attention has been paid to gas phase diffusion coefficients. Only a few previous studies have collected gas phase diffusion coefficients reported in the literature in order to assess the performance of theoretical calculations [19–22], and the number of molecules included in those studies is quite limited. Gordon [23] compiled a comprehensive list of references which reported experimentally measured gas phase diffusion coefficients; however, no data have been provided in this report [23].

In our previous work, we have compiled and evaluated gas phase diffusion coefficients of inorganic reactive trace gases in different bath gases [16] and organic reactive trace gases (containing no halogen atoms) in air (and N2/O2) [24]. We found that Fuller's semi-empirical method [22] could reliably estimate gas phase diffusivities (pressure-normalized diffusion coefficients), and differences between measured and estimated diffusivities using Fuller's method are typically less than 30% for inorganic compounds [16] and less than 10% for organic compounds [24]. It is further found that although diffusivities of different molecules in air vary largely, their Knudsen numbers at a given pressure are almost constant for a given particle size. This is because their mean free paths in air show little variation for different molecules. Expanding upon our previous studies [16,24], in this work, we have compiled experimentally measured gas phase diffusivities of organic halogens in a variety of bath gases reported in the literature. Organic halogens are of great environmental and climatic concern because they can be stratospheric ozone depletion species [25], greenhouse gases [26] and harmful pollutants [27–29]. It is found that measured diffusivities of organic halogens agree well with estimated values using Fuller's method. In addition, we propose a method based on mean free paths to calculate gas phase diffusivities. At a given temperature, this method only requires the average molecular speed (essentially only depending on its molecular mass) and the mean free path in the bath gas as input parameters. We have shown that the calculated diffusivities using our method agree quite well with measured values and those estimated using Fuller's method. Our method is particularly useful if the diffusion volumes of molecules of interest are unknown, i.e. when Fuller's method cannot be used due to lack of input parameters.

2. Theoretical background

The diffusion of molecules in fluids is driven by their concentration gradient, as described by Fick's first law [18]:

| 2.1a |

where J is the flux of molecules along the x-axis (molecule cm−2 s−1), and D* is the diffusion coefficient (cm2 s−1), n is the concentration of molecules (molecule cm−3) and x is the distance along the x-axis. Diffusion causes the concentration to change with time, given by Fick's second law [18]:

| 2.1b |

where t is the time (s). Equations (2.1a) and (2.1b) only consider diffusion along one dimension, and equations for diffusion in three dimensions can be found elsewhere [30]. It should be pointed out that typically D, instead of D*, is used for the diffusion coefficient. However, in this work, D has been reserved for the diffusivity (or pressure-independent diffusion coefficient) in order to be consistent with our previous work [16,24] as detailed below.

The gas phase diffusion coefficient, DP, depends on the pressure of the bath gas (P, in the unit of Torr) and is related to the diffusivity (or pressure-independent diffusion coefficient), D (Torr cm2 s−1), by the following equation [16]:

| 2.2 |

Gas phase diffusivities, when experimental data are not available, can be estimated using a variety of methods which vary in complexity and performance. Reid et al. [20] compared measured gas phase diffusivities of a large body of compounds with estimated values using several widely adopted methods. It was concluded that on average the semi-empirical method developed by Fuller et al. [21,22] shows the best performance. Fuller's method has also been used in our previous work to estimate gas phase diffusivities of inorganic compounds and organic compounds which do not contain halogen atoms [16,24], and in general good agreement of estimated values with experimental data has been found.

According to Fuller's method, the diffusivity of a trace gas X in a bath gas A can be calculated by the following equation:

| 2.3a |

where D(X,A) is the gas phase diffusivity of X in A (Torr cm2 s−1), T is the temperature (K), m(X,A) is the reduced mass of the molecular pair X-A (g mol−1), and VX and VA are the dimensionless diffusion volumes of X and A, respectively. The reduced molecular mass, m(X,A), can be calculated by the following equation:

| 2.3b |

where mX and mA are the molar masses (g mo1−1) of X and A, respectively. The diffusion volume of a molecule can be derived from the atomic diffusion volumes of atoms it contains, given by the following equation:

| 2.3c |

where ni is the number of the atom with a diffusion volume of Vi.

Table 1 lists atomic and structural diffusion volumes of common atoms and structures. In addition, the diffusion volumes of some small molecules, e.g. N2, H2O and CO2, are also given in table 1. If the diffusion volume of a molecule can be found in table 1, calculation of its diffusion volume using equation (2.3c) is unnecessary. The measured and estimated diffusivities in air are very close to those in N2 and O2 [24]. Therefore, as done in our previous study [24], we did not differentiate measured diffusivities in air, N2 and O2, and estimated diffusivities in N2 and O2 were also assumed to be equal to those in air. More details of description and discussion of Fuller's method can be found elsewhere [16,20,24].

Table 1.

Dimensionless diffusion volumes (V) of common atoms, structures and small molecules [20].

| species | C | H | O | N | S | aromatic ring |

| V | 15.9 | 2.31 | 6.11 | 4.54 | 22.9 | −18.3 |

| species | F | Cl | Br | I | heterocyclic ring | |

| V | 14.7 | 21 | 21.9 | 29.8 | −18.3 | |

| species | He | Ne | Ar | Kr | Xe | H2 |

| V | 2.67 | 5.98 | 16.2 | 24.5 | 32.7 | 6.12 |

| species | D2 | N2 | O2 | air | CO | CO2 |

| V | 6.84 | 18.5 | 16.3 | 19.7 | 18 | 26.9 |

| species | NH3 | H2O | SF6 | SO2 | Cl2 | Br2 |

| V | 20.7 | 13.1 | 71.3 | 41.8 | 38.4 | 69 |

3. Results

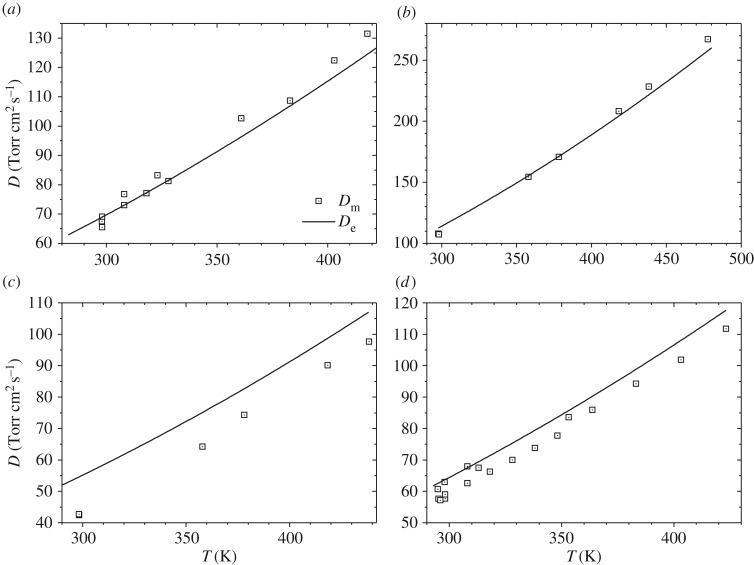

The measured gas phase diffusivities of 61 halogenated organic compounds in a variety of bath gases (including N2, air, H2, noble gases and some organic compounds) at different temperatures, reported by previous studies, are summarized in the electronic supplementary material together with corresponding estimated diffusivities using Fuller's method. This electronic supplementary material has been prepared in a similar format to that used in our previous work [16,24]. In addition, figure 1 displays measured and estimated diffusivities of CHCl3 in air, CH3Cl in CH4, CH3CH2Cl in CH3Cl and CCl4 in air at different temperatures as examples.

Figure 1.

Comparison of measured (Dm) and estimated diffusivities (De) as a function of temperature [31–39]. (a) CHCl3 in air, (b) CH3Cl in CH4, (c) CH2CH3Cl in CH3Cl and (d) CCl4 in air.

As evident from data contained in the electronic supplementary material and displayed in figure 1, measured diffusivities show good agreement with estimated values. Differences between the measured and estimated diffusivities are smaller than 10% for most of the data, and it is very rare for the differences to exceed 20%. It should also be noted that the entire dataset covers a wide temperature range from 273 to 478 K. Therefore, it can be concluded that Fuller's method can reliably estimate gas phase diffusivities of halogenated organic compounds as a function of temperature. Similar conclusions have been drawn in our previous work for inorganic compounds [16] and organic compounds which do not contain halogen atoms [24].

4. Discussion

An interesting question has been raised: can we estimate its diffusivity if the molecule contains atoms with diffusion volumes being unknown (i.e. not listed in table 1)? In our previous work [24], it has been found that for a given particle diameter, the Knudsen number (Kn), which is the ratio of the mean free path of gas molecules to the particle radius, is identical for different trace gases with very different diffusion coefficients. This is because different trace gases have almost the same molecule mean free paths in a given bath gas. The mean free path depends on pressure and temperature, and the relation between the pressure-normalized mean free path and the diffusion coefficient is given by the following equations [18,24]:

| 4.1a |

and

| 4.1b |

where DP(X,A) is the diffusivity (atm cm2 s−1) of X in A, λP(A) is the pressure-normalized mean free path (nm atm) in A and c(X) is the average molecular speed of X (cm s−1).

Our previous work [24] has shown that λP for air (and N2 and O2) calculated from diffusivities (measured or estimated using Fuller's method) and average molecular speeds of different molecules using equation (4.1b) are essentially identical. The mean free path in 1 atm air at 298 K is estimated to be 100 ± 20 nm [24]. Careful examination of fig. 3 in the paper published by Tang et al. [24] reveals that a value of approximately 90 nm may be more proper in general, especially for organic molecules. Within uncertainties, this shows fairly good agreement with the mean free path in air (approx. 67 nm in 1 atm air at 298 K) derived from viscosity data for air [40]. One reason to explain the difference in the mean free paths derived from diffusivities and viscosities is that the underlying assumption (made by classical gas kinetic theory) that gas molecules behave as hard spheres is not strictly valid. Compared to those derived from viscosity data, mean free paths derived from diffusivities data should be more accurate for the estimation of gas phase diffusivities.

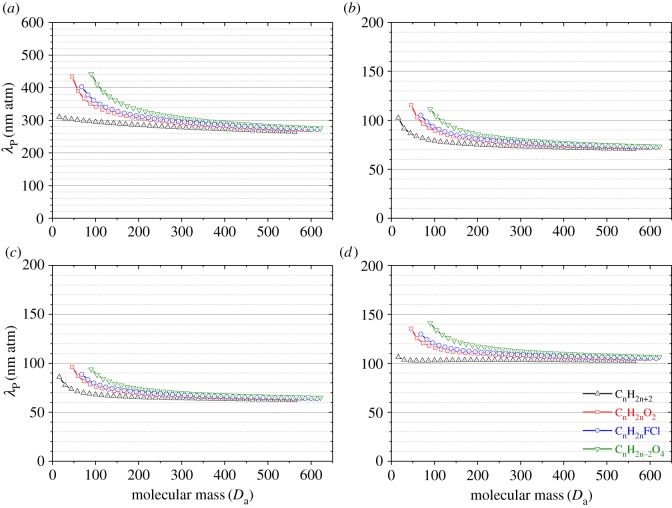

Using a similar procedure to Tang et al. [24], we first estimate diffusivities of four different groups of organic compounds (alkanes, alkanes with two hydrogen atoms replaced by one F atom and one Cl atom, monocarboxylic acids and dicarboxylic acids) in He, argon, CO2 and CH4 at 298 K using Fuller's method, and then calculate λP in He, argon, CO2 and CH4 using equation (4.1b). Figure 2 shows the results, suggesting that calculated λP are very similar for different trace gases in the same bath gas. The pressure-normalized mean free paths at 298 K, estimated using diffusivities, are calculated to be 350, 90, 80, 120 nm atm in He, argon, CO2 and CH4, respectively, and their uncertainties are estimated to be around ±25%. Pressure-normalized mean free paths can also be derived for other bath gases using the same approach as long as their diffusion volumes can be calculated using the atomic diffusion volumes given in table 1.

Figure 2.

Calculated pressure-normalized mean free paths in (a) He, (b) argon, (c) CO2 and (d) CH4 at 298 K as a function of molecular masses using equation (4.1b). Diffusivities are estimated using Fuller's methods for CnH2n+2 (alkanes), CnH2nO2 (monocarboxylic acid), CnH2nFCl (alkanes with two hydrogen atoms replaced by one F atom and one Cl atom) and CnH2n−2O4 (dicarboxylic acid) molecules with carbon atom numbers (n) ranging from 1 to 20.

Diffusivities can then be calculated from mean free paths, using equation (4.1a). Our previous work [24] implies that diffusivities of organic molecules (which do not contain halogen atoms) in air (and N2/O2) calculated using equation (4.1a) show good agreement with measured values and those estimated using Fuller's method. In our current work, we compare diffusivities in He at 298 K calculated using equation (4.1a) with those measured and estimated using Fuller's method, in order to further verify the applicability and reliability of equation (4.1a). He is chosen here because it has been widely used as bath gas in measurements of gas phase diffusion coefficients. If measurements were not carried out at 298 K, reported values have been extrapolated to those at 298 K using the temperature dependence given by the following equation [16]:

| 4.2 |

where D(T) and D(298 K) are the measured diffusivity at T (in K) and the extrapolated value at 298 K, respectively. If one study reported diffusivities at several temperatures, the measurement carried out at the temperature closed to 298 K is used.

Tables 2 and 3 list measured diffusivities (Dm) and those estimated using Fuller's method (De) and calculated using equation (4.1a) (Dc). It can be concluded that diffusivities calculated using equation (4.1a) agree fairly well with measured values. The differences between Dc and Dm are mostly within 30% for inorganic species (table 1) and within 20% for organic halogens (table 2). We note that overall the difference between Dc and Dm is larger than that between De and Dm, i.e. the performance of Fuller's method is better. However, estimation of diffusivities using Fuller's method requires the knowledge of molecular mass and diffusion volumes; if a molecule contains atoms whose diffusion volumes are not known (i.e. not listed in table 1), Fuller's method cannot be used. Therefore, although Fuller's method appears to be more accurate, equation (4.1a) provides a simpler and more generalized method which requires fewer parameters as input. This is particularly useful for molecules containing atoms whose diffusion volumes are not known. It should be pointed out that there are a few other methods which can be used to calculate the gas phase diffusivities [20], such as the Lennard–Jones method. However, the majority of existing methods require molecular parameters which are not readily available and can only be derived from molecular dynamics simulations. Reid et al. [20] evaluated the performance of several widely used methods and concluded that Fuller's method, though simpler than other methods, in general generates the smallest errors when compared with experimental data.

Table 2.

Comparison of diffusivities (Torr cm2 s−1) experimentally measured by previous work (Dm), estimated using Fuller's method (De), and calculated (Dc) using equation (4.1a) for inorganic compounds at 298 K.

| molecule | Dm | De | Dc | De/Dm | Dc/Dm | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO3 | 402 | 595 | 283 | 1.48 | 0.70 | [41] |

| HONO | 443 | 519 | 325 | 1.17 | 0.73 | [42] |

| 484 | 519 | 325 | 1.07 | 0.67 | [43] | |

| O3 | 415 | 528 | 322 | 1.27 | 0.78 | [44] |

| OH | 671 | 779 | 540 | 1.16 | 0.81 | [44] |

| 670 | 779 | 540 | 1.16 | 0.81 | [45] | |

| 622 | 780 | 540 | 1.25 | 0.87 | [46] | |

| HO2 | 410 | 594 | 388 | 1.45 | 0.95 | [44] |

| 435 | 594 | 388 | 1.37 | 0.89 | [46] | |

| HOBr | 369 | 412 | 226 | 1.12 | 0.61 | [47] |

| 311 | 412 | 226 | 1.32 | 0.73 | [48] | |

| HOI | 340 | 368 | 186 | 1.08 | 0.55 | [49] |

| ClNO2 | 317 | 374 | 247 | 1.18 | 0.78 | [50] |

| ICl | 302 | 320 | 175 | 1.06 | 0.58 | [51] |

Table 3.

Comparison of diffusivities (Torr cm2 s−1) experimentally measured by previous work (Dm), estimated using Fuller's method (De) and calculated (Dc) using equation (4.1a) for organic halogens at 298 K.

| gas | Dm | De | Dc | De/Dm | Dc/Dm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH3I | 312 | 316 | 187 | 1.01 | 0.60 |

| CH2F2 | 348 | 332 | 309 | 0.95 | 0.89 |

| CH2Cl2 | 303 | 293 | 242 | 0.97 | 0.80 |

| CH2Br2 | 268 | 292 | 169 | 1.09 | 0.63 |

| CHCl3 | 251 | 255 | 204 | 1.02 | 0.81 |

| CH3CH2Br | 298 | 291 | 213 | 0.98 | 0.72 |

| CH3CH2I | 261 | 269 | 178 | 1.03 | 0.68 |

| CH3CHF2 | 302 | 277 | 274 | 0.92 | 0.91 |

| CH2ClCH2Cl | 277 | 254 | 224 | 0.92 | 0.81 |

| CH3CH2CH2Cl | 255 | 252 | 252 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| CH3CH2CH2Br | 239 | 252 | 201 | 1.06 | 0.84 |

| CH3CHBrCH3 | 245 | 252 | 201 | 1.03 | 0.82 |

| CH3CH2CH2I | 232 | 236 | 171 | 1.02 | 0.74 |

| CH3CHICH3 | 232 | 236 | 171 | 1.02 | 0.74 |

| CH3CHBrCH2Cl | 231 | 225 | 178 | 0.98 | 0.77 |

| 1-chlorobutane | 223 | 225 | 232 | 1.01 | 1.04 |

| 2-chlorobutane | 225 | 225 | 232 | 1.00 | 1.03 |

| 1-bromobutane | 221 | 224 | 190 | 1.02 | 0.86 |

| 2-bromobutane | 224 | 224 | 190 | 1.00 | 0.85 |

| 1-iodobutane | 211 | 213 | 164 | 1.01 | 0.78 |

| 2-iodobutane | 221 | 213 | 164 | 0.97 | 0.74 |

| 1-chloropentane | 209 | 204 | 216 | 0.98 | 1.03 |

| 1-fluorohexane | 195 | 193 | 164 | 0.99 | 0.84 |

| 1-bromohexane | 186 | 188 | 173 | 1.01 | 0.93 |

| 2-bromohexane | 189 | 188 | 173 | 0.99 | 0.92 |

| 3-bromohexane | 188 | 188 | 173 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| fluorobenzene | 226 | 208 | 227 | 0.92 | 1.00 |

| chlorobenzene | 216 | 202 | 210 | 0.94 | 0.97 |

| bromobenzene | 220 | 202 | 178 | 0.92 | 0.81 |

| hexafluorobenzene | 182 | 166 | 163 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| 4-fluorotoluene | 202 | 191 | 212 | 0.95 | 1.05 |

5. Conclusion

In this work, we have compiled gas phase diffusivities (pressure-independent diffusion coefficients) of organic halogens in a variety of bath gases. It is found that estimated diffusivities using Fuller's semi-empirical method agree very well with experimental values reported in the literature, suggesting that Fuller's method can reliably estimate gas phase diffusivities of organic halogens. We also find that in addition to air (and N2/O2), within uncertainties the mean free paths of molecules are almost identical for a given bath gas. The pressure-normalized mean free paths at 298 K are estimated to be 90, 350, 90, 80, 120 nm atm in air (and N2/O2), He, argon, CO2 and CH4, respectively, with estimated errors of around ±25%. The pressure-normalized mean free paths in other bath gases, as long as diffusion volumes of bath gases can be calculated using the atomic volumes listed in table 1, can be derived using the same approach.

We further propose a generic method, based on mean free paths, to calculate gas phase diffusivities. Our proposed method only requires the mean free path in the bath gas and the average molecular speed of the trace gas (only depending on its molecular mass) as input parameters. The mean free path in a bath gas can be derived using the approach described in §4 as long as the diffusion volume of the bath gas can be calculated using atomic and structural diffusion volumes listed in table 1. Calculated diffusivities in He (and air/N2/O2 as well) using our method show reasonably good agreement with measured values and those estimated using Fuller's method. Our method is particularly useful when a trace gas contains atoms whose diffusion volumes are not known (i.e. when Fuller's method cannot be applied due to lack of input parameters).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank M. Kalberer (University of Cambridge, UK) for the helpful discussion.

Data accessibility

The datasets used by this article have been uploaded as electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

P.C. and M.T. designed the study; W.G. collected and analysed the data; W.G., P.C. and M.T. drafted the manuscript. All the authors gave their final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

Financial support provided by National Natural Science Foundation of China (91744204 and 91644106) is acknowledged. M.T. also thanks Chinese Academy of Sciences for providing a starting grant. This is contribution no. IS-2554 from GIGCAS.

References

- 1.Kolb CE, et al. 2010. An overview of current issues in the uptake of atmospheric trace gases by aerosols and clouds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 10 561–10 605. ( 10.5194/acp-10-10561-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang MJ, Cziczo DJ, Grassian VH. 2016. Interactions of water with mineral dust aerosol: water adsorption, hygroscopicity, cloud condensation and ice nucleation. Chem. Rev. 116, 4205–4259. ( 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00529) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pöschl U, Shiraiwa M. 2015. Multiphase chemistry at the atmosphere–biosphere interface influencing climate and public health in the Anthropocene. Chem. Rev. 115, 4440–4475. ( 10.1021/cr500487s) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George C, Ammann M, D'Anna B, Donaldson DJ, Nizkorodov SA. 2015. Heterogeneous photochemistry in the atmosphere. Chem. Rev. 115, 4218–4258. ( 10.1021/cr500648z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donaldson MA, Berke AE, Raff JD. 2013. Uptake of gas phase nitrous acid onto boundary layer soil surfaces. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 375–383. ( 10.1021/es404156a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wesely ML, Hicks BB. 2000. A review of the current status of knowledge on dry deposition. Atmos. Environ. 34, 2261–2282. ( 10.1016/S1352-2310(99)00467-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbatt JPD, et al. 2012. Halogen activation via interactions with environmental ice and snow in the polar lower troposphere and other regions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 6237–6271. ( 10.5194/acp-12-6237-2012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baergen AM, Donaldson DJ. 2016. Formation of reactive nitrogen oxides from urban grime photochemistry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 6355–6363. ( 10.5194/acp-16-6355-2016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sassine M, Burel L, D'Anna B, George C. 2010. Kinetics of the tropospheric formaldehyde loss onto mineral dust and urban surfaces. Atmos. Environ. 44, 5468–5475. ( 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.07.044) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nazaroff WW, Cass GR. 1989. Mass-transport aspects of pollutant removal at indoor surfaces. Environ. Int. 15, 567–584. ( 10.1016/0160-4120(89)90078-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye C, Gao H, Zhang N, Zhou X. 2016. Photolysis of nitric acid and nitrate on natural and artificial surfaces. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 3530–3536. ( 10.1021/acs.est.5b05032) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Descorme C, Gallezot P, Geantet C, George C. 2012. Heterogeneous catalysis: a key tool toward sustainability. ChemCatChem 4, 1897–1906. ( 10.1002/cctc.201200483) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen HH, Nanayakkara CE, Grassian VH. 2012. Titanium dioxide photocatalysis in atmospheric chemistry. Chem. Rev. 112, 5919–5948. ( 10.1021/cr3002092) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linsebigler AL, Lu G, Yates JT. 1995. Photocatalysis on TiO2 surfaces: principles, mechanisms, and selected results. Chem. Rev. 95, 735–758. ( 10.1021/cr00035a013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidovits P, Kolb CE, Williams LR, Jayne JT, Worsnop DR. 2011. Update 1 of: mass accommodation and chemical reactions at gas-liquid interfaces. Chem. Rev. 111, PR76–PR109. ( 10.1021/cr100360b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang MJ, Cox RA, Kalberer M. 2014. Compilation and evaluation of gas phase diffusion coefficients of reactive trace gases in the atmosphere: volume 1. Inorganic compounds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 9233–9247. ( 10.5194/acp-14-9233-2014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pöschl U. 2011. Gas–particle interactions of tropospheric aerosols: kinetic and thermodynamic perspectives of multiphase chemical reactions, amorphous organic substances, and the activation of cloud condensation nuclei. Atmos. Res. 101, 562–573. ( 10.1016/j.atmosres.2010.12.018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houston PL. 2001. Chemical kinetics and reaction dynamics. Dubuque and Boston: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marrero TR, Mason EA, 1972. Gaseous diffusion coefficients. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1, 3–118. ( 10.1063/1.3253094) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reid RC, Prausnitz JM, Poling BE. 1987. The properties of gases and liquids. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuller EN, Ensley K, Giddings JC. 1969. Diffusion of halogenated hydrocarbons in helium. Effect of structure on collision cross sections. J. Phys. Chem. 73, 3679–3685. ( 10.1021/j100845a020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuller EN, Schettle PD, Giddings JC. 1966. A new method for prediction of binary gas-phase diffusion coefficients. Ind. Eng. Chem. 58, 19–27. ( 10.1021/ie50677a007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon M. 1977. References to experimental data on diffusion coefficients of binary gas mixtures. Glasgow, UK: National Engineering Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang MJ, Shiraiwa M, Pöschl U, Cox RA, Kalberer M. 2015. Compilation and evaluation of gas phase diffusion coefficients of reactive trace gases in the atmosphere: Volume 2. Diffusivities of organic compounds, pressure-normalised mean free paths, and average Knudsen numbers for gas uptake calculations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 5585–5598. ( 10.5194/acp-15-5585-2015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solomon S. 1999. Stratospheric ozone depletion: a review of concepts and history. Rev. Geophys. 37, 275–316. ( 10.1029/1999RG900008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.IPCC. 2013. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nizzetto L, et al. 2010. Past, present, and future controls on levels of persistent organic pollutants in the global environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 6526–6531. ( 10.1021/es100178f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macleod M, Scheringer M, Podey H, Jones KC, Hungerbuhler K. 2007. The origin and significance of short-term variability of semivolatile contaminants in air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 3249–3253. ( 10.1021/es062135w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo Y, Yu HY, Zeng EY. 2009. Occurrence, source diagnosis, and biological effect assessment of DDT and its metabolites in various environmental compartments of the Pearl River Delta, South China: a review. Environ. Pollut. 157, 1753–1763. ( 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.12.026) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crank J. 1975. The mathematics of diffusion. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Getzinger RW, Wilke CR. 1967. An experimental study of nonequimolal diffusion in ternary gas mixtures. Aiche J. 13, 577–580. ( 10.1002/aic.690130331) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lugg GA. 1968. Diffusion coefficients of some organic and other vapors in air. Anal. Chem. 40, 1072–1077. ( 10.1021/ac60263a006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mrazek RV, Wicks CE, Prabhu KNS. 1968. Dependence of diffusion coefficient on composition in binary gaseous systems. J. Chem. Eng. Data 13, 508–510. ( 10.1021/je60039a014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cowie M, Watts H. 1971. Diffusion of methane and chloromethanes in air. Can. J. Chem. 49, 74–77. ( 10.1139/v71-011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watts H. 1971. Temperature dependence of diffusion of carbon tetrachloride, chloroform and methylene chloride vapors in air by a rate of evaporation method. Can. J. Chem. 49, 67–73. ( 10.1139/v71-010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gotoh S, Manner M, Sorensen JP, Stewart WE. 1974. Binary diffusion coefficients of low-density gases. 1. Measurements by modified Loschmidt method. J. Chem. Eng. Data 19, 169–171. ( 10.1021/je60061a025) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richardson JF. 1959. The evaporation of two-component liquid mixtures. Chem. Eng. Sci. 10, 234–242. ( 10.1016/0009-2509(59)80058-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pryde JA, Pryde EA. 1967. A simple quantitative diffusion experiment. Phys. Educ. 2, 311–314. ( 10.1088/0031-9120/2/6/001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grob AK, Elwakil MM. 1969. An interferometric technique for measuring binary diffusion coefficients. J. Heat Trans. 91, 259–265. ( 10.1115/1.3580138) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jennings SG. 1988. The mean free path in air. J. Aerosol. Sci. 19, 159–166. ( 10.1016/0021-8502(88)90219-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rudich Y, Talukdar RK, Imamura T, Fox RW, Ravishankara AR. 1996. Uptake of NO3 on KI solutions: rate coefficient for the NO3+I− reaction and gas-phase diffusion coefficients for NO3. Chem. Phys. Lett. 261, 467–473. ( 10.1016/0009-2614(96)00980-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirokawa J, Kato T, Mafune F. 2008. Uptake of gas-phase nitrous acid by pH-controlled aqueous solution studied by a wetted wall flow tube. J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 12 143–12 150. ( 10.1021/jp8051483) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El Zein A, Bedjanian Y. 2012. Reactive uptake of HONO to TiO2 surface: ‘dark’ reaction. J. Phys. Chem. A 116, 3665–3672. ( 10.1021/jp300859w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ivanov AV, Trakhtenberg S, Bertram AK, Gershenzon YM, Molina MJ. 2007. OH, HO2, and ozone gaseous diffusion coefficients. J. Phys. Chem. A 111, 1632–1637. ( 10.1021/jp066558w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bertram AK, Ivanov AV, Hunter M, Molina LT, Molina MJ. 2001. The reaction probability of OH on organic surfaces of tropospheric interest. J. Phys. Chem. A 105, 9415–9421. ( 10.1021/jp0114034) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Ivanov AV, Molina MJ. 2009. Temperature dependence of OH diffusion in air and He. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L03816 ( 10.1029/2008GL036170) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fickert S, Adams JW, Crowley JN. 1999. Activation of Br2 and BrCl via uptake of HOBr onto aqueous salt solutions. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 104, 23 719–23 727. ( 10.1029/1999JD900359) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adams JW, Holmes NS, Crowley JN. 2002. Uptake and reaction of HOBr on frozen and dry NaCl/NaBr surfaces between 253 and 233 K. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2, 79–91. ( 10.5194/acp-2-79-2002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holmes NS, Adams JW, Crowley JN. 2001. Uptake and reaction of HOI and IONO2 on frozen and dry NaCl/NaBr surfaces and H2SO4. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 3, 1679–1687. ( 10.1039/b100247n) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fickert S, Helleis F, Adams JW, Moortgat GK, Crowley JN. 1998. Reactive uptake of ClNO2 on aqueous bromide solutions. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 10 689–10 696. ( 10.1021/jp983004n) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Braban CF, Adams JW, Rodriguez D, Cox RA, Crowley JN, Schuster G. 2007. Heterogeneous reactions of HOI, ICl and IBr on sea salt and sea salt proxies. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 9, 3136–3148. ( 10.1039/b700829e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used by this article have been uploaded as electronic supplementary material.