Highlights

-

•

Midgut volvulus secondary to intestinal malrotation is a rare cause of acute abdomen in adults.

-

•

There are only 92 reported cases in the literature.

-

•

Diagnosis of the midgut volvulus was predominantly made via CT (67%) but also by ultrasound (15%) and theatre (18%).

-

•

Midgut volvulus is associated with a high risk of ischaemia and necrosis of bowel supplied by the SMA (35).

-

•

There is a 5% associated mortality rate.

Keywords: Case report, Intestinal malrotation, Midgut volvulus, Ladds bands

Abstract

Introduction

Midgut volvulus secondary to intestinal malrotation is a rare cause of an acute abdomen in adults, with 92 confirmed cases in the literature. Incidence of malrotation is estimated 1 in 6000 live births. 64–80% of malrotation cases present in the first month of life and 90% within the first year. Adult presentation is very rare accounting for only 0.2–0.5% of cases, of which only 15% present with midgut volvulus.

Presentation of case

We report a rare case of a 20 year old male with spontaneous midgut volvulus secondary to congenital malrotation of the bowel. Additionally we performed a literature review and analysis of the 92 cases of adult presentations of midgut volvulus secondary to malrotation.

Discussion

Of the 92 cases, average patient age was 40 years old and a 1.7:1 male:female ratio. Diagnosis of midgut volvulus was predominantly made via CT (67%) but also by ultrasound (15%) and theatre (18%). Midgut volvulus is associated with a high risk of ischaemia and necrosis of bowel supplied by the SMA (35). 19% of cases reported required a bowel resection. The case discussed in this report required a 130 cm bowel resection which is similar to the mean bowel resection length in the literature of 121 cm. Mean associated mortality rate is 5%.

Conclusion

This case reinforces the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion and closely monitoring patients presenting with non-specific abdominal pain, to allow early recognition and management of rare causes of the deteriorating surgical patient.

1. Introduction

Midgut volvulus secondary to intestinal malrotation is a rare cause of an acute abdomen in adults [1]. Incidence of malrotation is extrapolated from post mortem studies at 1 in 6000 live births; however true incidence is difficult to ascertain as some cases remain asymptomatic [1]. Furthermore this incidence will likely continue to increase as incidental diagnosis of malrotation increases secondary to advances in imaging [2]. The majority (64–80%) of malrotation cases present in the first month of life and 90% within the first year [2]. Adult presentation is very rare accounting for only 0.2–0.5% of cases, of which only 15% present with midgut volvulus [[3], [4], [5]]. We report a rare case of a 20 year old male with spontaneous midgut volvulus of the jejunum and ileum secondary to congenital malrotation of the bowel. This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [6].

2. Presentation of case

A 20 year old male presented Emergency Department (ED) with sudden onset ‘throbbing’ epigastric abdominal pain, which he rated as 8 out of 10 in severity. The pain had started 9 h previously and intermittently radiated to his back. He had experienced some associated nausea and had two episodes of vomiting. The patient had experienced no change of bowel habit, bleeding per rectum, fevers, dysuria and systematic review was unremarkable. He had no previous abdominal operations, no significant past medical or family history and took no regular medications.

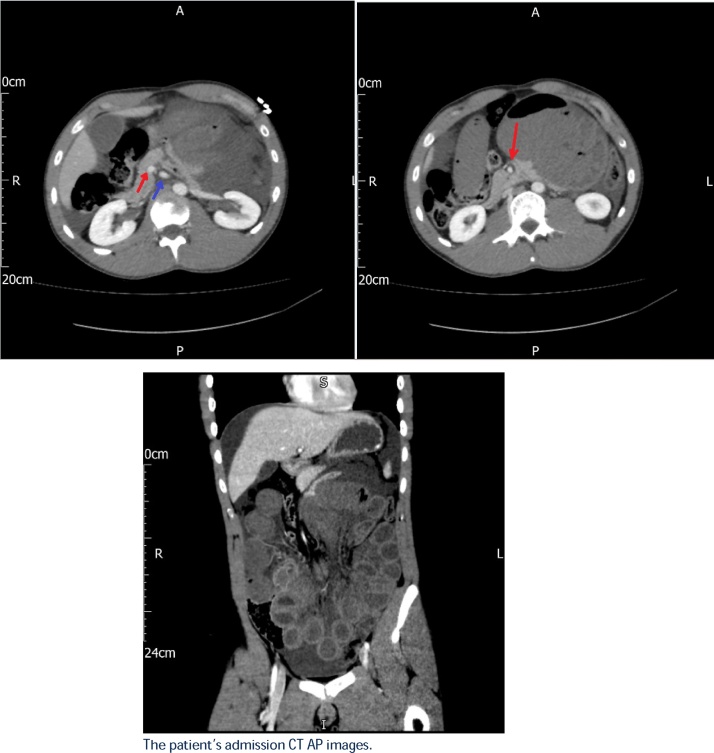

On examination he was tachycardic at 120 but his other vitals were normal. He had generalised abdominal tenderness, with voluntary guarding but no evidence of peritonism. His abdomen was mildly distended. Further systemic examination was unremarkable. Blood tests were relatively unremarkable, with a white cell count of 11 × 109 L−1, Hb 158 g L−1, Plts 189 × 109 L−1, CRP 1 mg L−1. Urea and electrolytes and liver function tests were within normal range. His initial lactate on presentation was 4.6 mmol/L, which subsequently rose to 8.6 mmol/L when repeated 2 h later. Plain abdominal and chest films were unremarkable, with no free air under the diaphragm or bowel dilatation present. Initially the patient was treated with analgesia plus fluids and an abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) was requested (Fig. 1). The CT demonstrated a midgut volvulus, with a collapsed proximal jejunal loop and dilated distal jejunal segment, featureless tapering around root of mesentery, in addition to a possible superior mesenteric artery (SMA) thrombosis.

Fig. 1.

CT images demonstrating midgut volvulus. 1a (top left) shows the abnormal superior mesenteric artery-vein (SMA-SMV) relationship associated with intestinal malrotation; with the SMV (marked with a blue arrow) being to the left of SMA (marked with red arrow). 1b (top right) shows an axial view and 1c (bottom) a coronal view of the pathognomonic ‘whirlpool’ sign associated with midgut volvulus. This characteristic appearance demonstrating the wrapping of the mesentery and SMV around the SMA (marked with red arrow).

Following the CT and 4 h after presenting, a decision was made to proceed with an explorative midline laparotomy. The significant findings included a volvulus of the small bowel, with a 540° clockwise mesenteric twist; as well a high riding caecum and presence of Ladds bands suggesting malrotation. An ischaemic looking segment appearing purple and oedematous, ran from the proximal jejunum to distal ileum, approximately 20 cm from the ileocecal (IC) valve. Following reduction and restoration of normal mesenteric orientation, there was signs of reperfusion and improvement in the appearance of the ischaemic segment.

At the 4 h re-look, the appearance of the small bowel had continued to improve; with approximately 70 cm proximal to the IC valve now appearing viable, and only some persistent patchy haemorrhagic changes in the remaining small bowel. A second re-look was organised for the following morning and the patient returned to ITU for continued resuscitation and optimisation. However prior to this second re-look, the patient became haemodynamically unstable and required increased inotropic support. The patient was immediately taken back to theatre whereby he had a 120 cm frankly ischaemic segment of bowel, from 130 cm distal to the DJ flexure and 20 cm proximal to the IC valve. The ischaemic bowel segment was resected and laparostomy dressing re-applied. The patient returned on day 3 for further evaluation of viability of the remaining bowel and there was no evidence of further ischemia, hence a side-to-side anastomosis was performed at this point. The patient’s post operative recovery was complicated by ICU delirium requiring high levels of sedation and a prolonged ileus requiring TPN. The patient was de-escalated to a surgical ward on day 10 and discharged on day 24.

3. Discussion

Intestinal malrotation is thought to be secondary to a failure of the bowel during embryogenesis, as it elongates and herniates into the base of the umbilical cord, to rotate 270° counterclockwise around the axis of the SMA [[7], [8], [9]]. The degree the bowel has failed to undergo this physiological rotation can vary and hence there are different classifications of malrotation [3]. The Stringer classification states there are 3 forms of malrotation; type 1 non-rotation, type 2 duodenal malrotation and type 3 duodenal plus caecal malrotation [10]. The patient discussed in this case report had type 1 non-rotation malrotation, hence this will be the focus of our discussion. Non-rotation malrotation is characterised by malposition of the bowel and malfixation of the mesentery [10].

The bowel position associated with normal rotation has the duodenojejunal (DJ) flexure left of the midline at L1 and the terminal ileum located in the right iliac fossa (RIF) [11]. Bowel position associated with type 1 malrotation however has the small bowel mainly located in right hemiabdomen and large bowel in left hemiabdomen; with an absence of the ligament of Treitz [10]. This abnormal bowel position results in an ectopic location of the appendix [12]. Ely et al. described 8 cases by which the diagnosis of appendicitis was delayed in intestinal malrotation patients due to unorthodox clinical presentations such as left sided pain [13]. Other characteristic abdominal abnormalities associated with type 1 malrotation include inversion of the superior mesenteric vessels and hypoplasia of the pancreatic uncinate process [9,[13], [14], [15], [16]]. These characteristic abnormalities are often identified incidentally on CT when malrotation patients are being investigated, however diagnosis is still often delayed or missed [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. Clinicians and radiologists must therefore have a high level of suspicion of intestinal malrotation should these abnormalities be highlighted by CT [16].

Malfixation of the mesentery results in a narrow mesenteric pedicle predisposed to volvulus [18]. Abnormal peritoneal attachments from the right lateral abdominal wall and liver to the caecum (Ladds bands) predisposes to bowel obstruction via external compression of the duodenum and jejunum [18]. Ladd’s bands are so named after William Ladd, who first described the surgical removal of these fibrous bands in 1932 [19].

The exact aetiology of malrotation remains uncertain but some studies have indicated a genetic component. Martin et al identified an association between malrotation and mutations in the forkhead box transcription factor (FOXF1) and L–R asymmetry genes [20]. Furthermore intestinal malrotation features in various syndromes associated with other GI tract malformations, with evidence of both autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance patterns [20]. For example, Martinez-Frias syndrome comprises of malrotation, as well as multiple gastrointestinal tract (GI) atresias and abnormalities of the pancreas plus biliary system [20]. Nath et al. presented 2 cases of a brother and sister both presenting with midgut volvulus within 18 months of each other [21]. GI abnormalities including malrotation has also be linked to chromosomal abnormalities such as trilogy of the long arm of chromosome 16 and a ring chromosome 4 [22,23].

Clinical presentation of intestinal malrotation correlates with the age of presentation, with infants commonly presenting with midgut volvulus, whilst only accounting for 15% of adult presentations [1,[3], [4], [5]]. Adult presentations of malrotation can be broadly split into incidental, chronic and acute. The incidental presentation of malrotation often occurs in asymptomatic patients who undergo investigative imaging and laparotomies for alternative health conditions, which subsequently highlights malrotation [24,25]. The chronic presentations of malrotation tend to be more insidious with patients experiencing non specific GI symptoms over a protracted period of time [21,24,25]. Symptoms can be vague and remitting over months or years. Patients are often extensively investigated by a number of specialities and often a diagnosis only reached via CT or exploratory laparotomy [21]. Common symptoms include intermittent crampy abdominal pain, bloating, weight loss and nausea/vomiting [18,21,26]. It is theorised these patients are experiencing either intermittent bowel obstruction due to Ladd band compression or intermittent midgut volvulus [26,27].

There was 92 adult cases of intestinal malrotation presenting acutely with midgut volvulus described in the published literature [4,8,10,12,15,17,18,21,24,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. The average age of presentation was 40 years old and there was a 1.7:1 ratio of male to female preponderance [4,8,10,12,15,17,18,21,24,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. The most common presenting symptoms were severe epigastric or umbilical pain, nausea and vomiting and distension; and all these symptoms were experienced by the patient in this case report [4,8,10,12,15,17,18,21,24,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. Diagnosis of the midgut volvulus was predominantly made via CT (67%) but also made via ultrasound (15%) and intra-operatively (18%) [4,8,10,12,15,17,18,21,24,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. The pathognomonic CT findings associated with midgut volvulus are the ‘whirlpool sign’ of the mesentery and SMV wrapped around the SMA, and the ‘beak’ like appearance of the obstructed proximal jejunum [12,14,36,40]. Additional CT findings associated with midgut volvulus secondary to malrotation include the abnormally orientated mesenteric vessels with the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) being situated the left or vertical to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and the underdevelopment of the uncinate process of the pancreas [7,12,14,36,40]. In the presence of midgut volvulus, there is a high risk of bowel ischaemia and necrosis to the bowel supplied by the SMA (35). Of the 92 midgut volvulus cases, 19% required a bowel resection, with an average resection length of 121 cm [4,8,10,12,15,17,18,21,24,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. There was an associated 5% mortality with midgut volvulus [4,8,10,12,15,17,18,21,24,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. The case discussed in this report required a 130 cm bowel resection.

The management of midgut volvulus is the Ladds procedure. The procedure involves 4 steps: firstly counterclockwise detorsion of the volvulus, secondly division of Ladds bands, thirdly broadening of the narrow small bowel mesentery and finally division of adhesions around the SMA [40]. Additionally the small bowel is often placed along the right lateral gutter and colon in the left, as well as an incidental appendectomy performed [40].

4. Conclusion

We report a rare case of a 20 year old male presenting acutely with a midgut volvulus secondary to intestinal malrotation, subsequently requiring a resection of gangrenous bowel. This case emphasises the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for this insidious condition in addition to closely monitoring such patients. This allows prompt recognition and management of this rare cause of the deteriorating surgical patient optimising patient outcomes.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interests to declare.

Funding

No sources of funding for research to declare.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval has been exempted by my institution.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Authors contribution

Mr William A Butterworth designed the study with the help of the colleague below, collected the data from notes with help of colleague as documented below, wrote first draft of the paper and continued to edit and amend the paper with decisive help and input from Dr James W Butterworth.

Dr James W Butterworth helped in acquisition of data from notes, helped revise critically important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be submitted.

Registration of research studies

NA.

Guarantor

William A Butterworth.

Contributor Information

William A. Butterworth, Email: william.butterworth@nhs.net.

James W. Butterworth, Email: jamesfomsf@googlemail.com.

References

- 1.Fischer J., Bland K. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. Mastery of Surgery. ISBN 078177165X. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emanuwa O., Ayantunde A. Midgut malrotation first presenting as acute bowel obstruction in adulthood: a case report and literature review. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-6-22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3158108/ URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres A., Ziegler M. Malrotation of the intestine. World J. Surg. 1993;17:326–331. doi: 10.1007/BF01658699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fung A. Malrotation with midgut volvulus in an adult: a case report and review of the literature. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2017;(May) doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjx081. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5441244/ URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Low S., Ngiu C. Midgut malrotation with congenital peritoneal band: a rare cause of small bowel obstruction in adulthood. BMJ Case Rep. 2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202690. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3948007/ URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pickhardt P., Bhalla S. Intestinal malrotation in adolescents and adults. Spectrum of clinical and imaging features. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2002:1429–1435. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sozen S., Guzel K. Intestinal malrotation in an adult: case report. Turk. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2012 doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2012.60973. https://www.journalagent.com/travma/pdfs/UTD-60973-CASE_REPORTS-SOZEN.pdf URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Applegate K., Anderson J. Intestinal malrotation in children: a problem-solving approach to the upper gastrointestinal series. RSNA. 2006 doi: 10.1148/rg.265055167. http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/full/10.1148/rg.265055167 URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bektasoglu H., Idiz U. Midgut malrotation causing intermittent intestinal obstruction in a young adult. Case Rep. Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/758032. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4054901/ URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell D., Gaillard F. Intestinal malrotation. Radiopaedia. 2017 https://radiopaedia.org/articles/intestinal-malrotation URL: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng Z., Huang J. Adult congenital intestinal malrotation accompanied by midgut volvulus: report of eight cases. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4100975/ URL: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ely B., Gorelik N. Appendicitis in adults with incidental midgut malrotation: CT findings. Clin. Radiol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2013.07.001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23937823 URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang B., Chen W. Adult midgut malrotation: multi-detector computed tomography findings of 14 cases. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11604-013-0194-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23475600 URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soker G., Yilmaz C. An unexpected cause of small bowel obstruction in an adult patient: midgut volvulus. BMJ Case Rep. 2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-205178. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4025217/ URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bozlar U., Ugurel M. CT angiographic demonstration of a mesenteric vessel “whirlpool” in intestinal malrotation and midgut volvulus: a case report. Kor. J. Radiol. 2008 doi: 10.3348/kjr.2008.9.5.466. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18838858 URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duran C., Ozturk E. Midgut volvulus: value of multidetector computed tomography in diagnosis. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2008 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23712366_Midgut_volvulus_Value_of_multidetector_computed_tomography_in_diagnosis URL: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haak B., Bodewitz S. Intestinal malrotation and volvulus in adult life. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.02.013. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4008858/ URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ladd W. New Engl. J. Med. 1932;206(6) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin V., Shaw-smith C. Review of genetic factors in intestinal malrotation. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2010;26(8):769–781. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2622-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nath J., Corder A. Delayed presentation of familial intestinal malrotation with volvulus in two adult siblings. RCS Ann. 2015 doi: 10.1308/003588412X13373405384819. https://publishing.rcseng.ac.uk/doi/abs/10.1308/003588412X13373405384819 URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brisset S., Joly G. Molecular characterization of partial trisomy 16q24.1-qter: clinical report and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10740. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12457405 URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balci S., Engiz O. Ring chromosome 4 and Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome (WHS) in a child with multiple anomalies. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2006 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31131. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16470698 URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen Z., Kleiner O. How much of a misnomer is “asymptomatic” intestinal malrotation? Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2003 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12725135 URL: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang C., Welch C. Anomalies of intestinal rotation in adolescents and adults. Surgery. 1963 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14087118 URL: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wanjari A., Deshmukh A. Midgut malrotation with chronic abdominal pain. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2012 doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.94950. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3334262/ URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Von Flue M. Acute and chronic presentation of intestinal nonrotation in adults. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1994 doi: 10.1007/BF02047549. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8306846/ URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zengin A., Ucar B. Adult midgut malrotation presented with acute bowel obstruction and ischemia. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.03.018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4844668/ URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu S., Yu J. Midgut volvulus in an adult with congenital malrotation. Am. J. Surg. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.01.044. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002961008000561 URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siwat S., Noor M. Endoscopic management of a pregnant lady with duodenal obstruction due to malrotation with midgut volvulus. Trop. Gastroenterol. 2012 http://www.tropicalgastro.com/articles/32/4/endoscopic-management-of-a-pregnant.html URL: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu C., Berger A. Intestinal necrosis with midgut malrotation and intermittent volvulus: presentation as acute abdominal pain in an adult. J. Emerg. Med. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.05.025. http://www.jem-journal.com/article/S0736-4679(16)30155-X/fulltext URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaikwad A., Ghongade D. Fatal midgut volvulus: a rare cause of gestational intestinal obstruction. Abdom. Imaging. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00261-009-9519-6. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24407840_Fatal_midgut_volvulus_A_rare_cause_of_gestational_intestinal_obstruction URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bozlar U., Ugurel M. CT angiographic demonstration of a mesenteric vessel “whirlpool” in intestinal malrotation and midgut volvulus: a case report. Korean J. Radiol. 2008 doi: 10.3348/kjr.2008.9.5.466. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2627208/ URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukuya T., Brown B. Midgut volvulus as a complication of intestinal malrotation in adults. Digest. Dis. Sci. 1993 doi: 10.1007/BF01316496. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01316496 URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeh W., Wang H. Preoperative sonographic diagnosis of midgut malrotation with volvulus in adults: the “whirlpool” sign. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 1999 doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199906)27:5<279::aid-jcu8>3.0.co;2-g. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0096(199906)27:5%3C279::AID-JCU8%3E3.0.CO;2-G/full URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Husberg B., Salehi K. Congenital intestinal malrotation in adolescent and adult patients: a 12-year clinical and radiological survey. Springerplus. 2016 doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1842-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4771654/ URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ordonez A., Nguyen D. Midgut volvulus in an adult. 2003. Wandering liver and intestinal malrotation: first report. Surg. Case Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1186/s40792-016-0205-y. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4975732/ URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esterson Y., Villani R. Small bowel volvulus in pregnancy with associated superior mesenteric artery occlusion. Clin. Imaging. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2017.01.002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28126700 URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotobi H., Tan V. Total midgut volvulus in adults with intestinal malrotation. Report of eleven patients. J. Visceral Surg. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2016.06.010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27888039 URL: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shahverdi E., Morshedi M. Utility of the CT scan in diagnosing midgut volvulus in patients with chronic abdominal pain. Case Rep. Surg. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/1079192. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28182093 URL: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]