Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a gasotransmitter that regulates cellular homeostasis and impacts on multiple physiological and pathophysiological processes. However, it exerts many of its biological actions indirectly via the formation of H2S-derived sulfane sulfur species/polysulfides. Because of the high reactivity of sulfur species, the detection of H2S-derived polysulfides in biological systems is challenging and currently used methods are neither sensitive nor quantitative. Herein, we describe a LC-MS/MS-based method that makes use of Sulfane Sulfur Probe 4 to detect endogenously generated polysulfides in biological samples in a selective, sensitive and quantitative manner. The results indicate a large variability in the activity of the H2S-generating enzymes in different murine organs, but the method described was able to detect intracellular levels of polysulfides in the nanomolar range and identify cystathionine γ-lyase as the major intracellular source of sulfane sulfur species/polysulfides in murine endothelial cells and hearts. The protocol described can be applied to a variety of biological samples for the quantification of the H2S-derived polysulfides and has the potential to increase understanding on the control and consequences of this gaseous transmitter.

Keywords: Polysulfide quantification, LC-MS/MS, SSP4, Biological samples

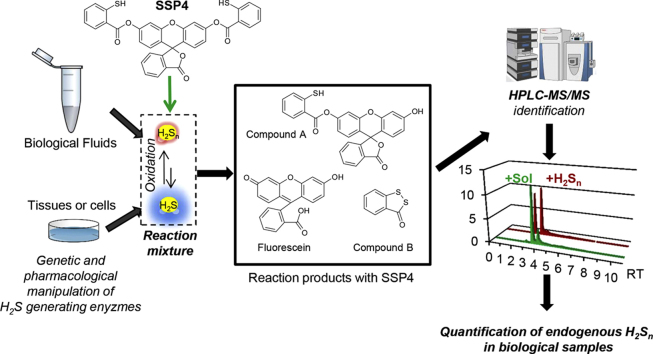

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a ubiquitously generated gaseous signaling mediator, or “gasotransmitter” that plays an important role in the regulation of numerous cellular functions, as well as physiological and pathophysiological processes [1]. In mammalian cells H2S is predominately produced during the metabolism of L-cysteine by two pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-dependent enzymes i.e. cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS), and cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE), or during the catabolism of 3-mercaptopyruvate by 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3MST) [2], [3]. H2S generating enzymes show distinct tissue-specific distribution patterns and intracellular compartmentalization [1].

Abnormal H2S production has been associated with different pathological states in the gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and central nervous systems [4]. However, it is currently difficult to convincingly link H2S with specific pathologies because of the lack of a widely accepted, easy to use, sensitive and selective assay for its quantification. The reliable detection of H2S in biological samples is hampered by the fact that the gas is volatile, redox reactive and steady-state concentrations are low [3]. These difficulties, combined with the use of methods that are not specific for measurement of free sulfides at physiological pH, have resulted in reports of H2S concentrations spanning five orders of magnitude i.e. ranging from the low nanomolar to hundreds of micromolar range [5], [6]. This ambiguity in the physiologically relevant concentration of H2S has, in turn, resulted in the use of widely varying concentrations of sulfide donors to elicit physiological effects.

H2S-related sulfane sulfur compounds include persulfides (R-S-SH), polysulfides (R-Sn-SH or R-S-Sn-S-R), inorganic hydrogen polysulfides (H2Sn, n ≥ 2) and protein-bound elemental sulfur (S8). Recent studies have suggested that polysulfides are generated endogenously following oxidation of the endogenously released H2S and can serve as a sink of H2S. Indeed, many of the biological effects currently attributed to H2S may in fact be due to polysulfides [7]. Current methods used for the detection of H2S and polysulfides include the colorimetric assay of methylene blue formation, a sulfide ion-selective or a polarographic electrode, gas chromatography with flame photometric or sulfur chemiluminescence detection, ion chromatography, HPLC analysis of the monobromobimane derivative of sulfide, and the use of sulfide-sensitive fluorescent dyes (for review see [8]). Few of these different methods can be applied to living cells because of their destructive nature. More recently, luminescence probes have been used to detect H2S, however, the biological applications of this technique require advanced imaging equipment and the selectivity of the method has been questioned [7]. The aim of this study, therefore, was to develop a sensitive LC-MS/MS based method for the detection of endogenously generated H2S-derived polysulfides and hydropersulfides in living cells and tissues as well as in frozen samples. The assay is based on the reaction of polysulfides with Sulfane Sulfur Probe 4 (SPP4), which has been used by several research groups [9], [10], [11].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Sulfane Sulfur Probe 4 (SSP4) and sodium trisulfide (Na2S3) were from Sulfobiotics (Dojindo EU GmbH, Munich, Germany), cell culture media were from Gibco (Invitrogen; Darmstadt, Germany) and the phenol red-free endothelial cell growth medium (EGM) was from PELObiotech (Planegg/Martinsried, Germany). Sodium polysulthionate (SG1002) was from Sulfagenix Inc. (Melbourne, Australia) and 2-[(4-hydroxy-6-methylpyrimidin-2-yl)sulfanyl]-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethanone (Inhibitor 3) was from Molport (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany). The anti-CSE antibody was from Proteintech (Manchester, UK), anti-CBS was from Abnova (Germany), anti-3MST was from Atlas (Bromma, Sweden), the antibody against telomerase was from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Secondary anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies were obtained from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). The antibody against β-actin was from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany) and all other chemicals and reagents were purchased either from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany) or AppliChem (Darmstadt, Germany).

2.2. Animals

CSE-/- mice and floxed CSE (C57/Bl6J CSEfl/fl) mice [12] were kindly provided by Josef Pfeilschifter (Frankfurt, Germany). CSEfl/fl mice were crossed with tamoxifen-inducible Cdh5-CreERT2 mice [13], to generate animals specifically lacking CSE in endothelial cells (CSEiΔEC mice) as described [14]. Mice were housed in conditions that conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH publication no. 85-23). Animals received standard chow and 8–10 week old mice of both genders were studied.

2.3. Cell isolation and culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were isolated and cultured as described [15], and confluent cells up to passage 1 were used. The use of human material in this study conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and the isolation of endothelial cells was approved in written form by the ethics committee of the Goethe University. Murine lung endothelial cells were isolated from either wild-type or CSEiΔEC mice and cultured up to passage 8, as described [16].

For H2Sn determination, cells were seeded to 48 well plates pre-coated with fibronectin. To induce CSE deletion, cells from untreated CSEiΔEC mice (passage 4) were treated in vitro with 4-OH-tamoxifen (Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany) for 7 days. Thereafter, 4-OH-tamoxifen was removed and the cells were passaged for additional 3 times before use, as a control, endothelial cells from wild-type mice were also treated with 4-OH-tamoxifen.

2.4. Adenoviral generation and infection protocols

Adenoviruses for the overexpression of green fluorescent protein (GFP), CBS, CSE and 3MST were generated as described [17], [18], [19]. Human endothelial cells (passage 1, 80% confluent) and murine endothelial cells (passage 5–8, 80% confluent) were starved of serum for 4 h in endothelial growth medium (EGM) containing 0.1% BSA. Adenoviruses (10 MOI) were incubated for 30 min with AdenoBoost (Sirion Biotech GmbH, Martinsried, Germany) and then added to the endothelial cells for 4 h (37 °C). The culture medium was then replaced and cells were maintained in culture for 24 h before H2Sn generation was measured.

2.5. Platelet isolation

Platelets were obtained by centrifugation (900g, 7 min) of platelet-rich plasma, as described [20]. The resulting pellet was washed in Ca2+-free HEPES buffer (mM: NaCl, 136; KCl, 2.6; MgCl2, 0.93; NaH2PO4, 3.26; glucose, 5.5; HEPES, 3.7; pH 7.4 at 37 °C) and samples were re-suspended in HEPES buffer.

2.6. Immunoblotting

Samples (cells or tissues) were lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer (mM: 50 Tris HCl pH 7.5, 150 NaCl, 25 NaF, 10 Na4P2O7, 1% Triton X‐100 and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) and total proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, subjected to Western blotting and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence using a commercially available kit (Amersham, Freiburg, Germany), as described [16].

2.7. Methylene Blue measurement

Methylene Blue detection was performed as described [21] and a standard curve of NaHS in ddH2O (up to 100 µM) was used for quantification.

2.8. 7-Azido-4-Methylcoumarine (AzMc) assay

The reaction of AzMC to sulfur products was evaluated as described [22] and a standard curve of NaHS in ddH2O (up to 100 µM) was used for quantification.

2.9. Sample preparation

2.9.1. Assay of H2Sn in cultured cells

Culture medium was removed from confluent cultures of cells and washed once with warm Hanks buffer. EGM supplemented with 0.1% BSA (200 µL) was added and after 2 h was substituted with phenol-free EGM containing SSP4 (10 μM; always prepared freshly and kept in the dark). Depending on the aims of particular experiments the medium was supplemented with either substrates; L-cysteine (L-Cys, 100 μM), L-homocysteine (L-Hcy, 100 μM), 3-mercaptopyruvate (3MP, 100 μM) and pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP, 10 μM) or inhibitors; aminoxy-acetate (AOAA, 1 mM), DL-proparglycine (PAG, 1 mM) and Inhibitor 3 (10 μM). Solvent-treated groups contained a final concentration of 0.1% DMSO. After 60 min (37 °C), the cell supernatant was collected in Eppendorf tubes and any detached cells were removed by centrifugation at 16,000g (4 °C, 10 min). Then 80% of the supernatant was collected for LC-MS/MS or fluorescence measurements. Thereafter, the cell pellet was washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer for immunoblotting.

To determine whether or not SSP4 was cell permeable, experiments were repeated as above, with the exception that the cell pellet was washed twice with PBS and snap frozen in liquid N2. For the quantification of H2Sn production, standard curves of fluorescein and SSP4 were generated in EGM. In each experiment EGM and EGM containing SSP4 were included as negative controls and EGM containing SSP4 and SG1002 (10 μM) as positive control.

2.9.2. Assay of H2Sn in different cellular subcompartments

Confluent cultures of human endothelial cells (in 6 cm Petri dishes) were washed twice with PBS and harvested by scraping followed by centrifugation (1000g, 5 min, RT). The cell supernatant was discarded and ice cold extraction buffer containing HEPES pH 7.6 (10 mM), KCl (10 mM), EDTA (0.1 mM), EGTA (0.1 mM), NP-40 (0.1%) and phosphatase and protease inhibitors was added to the cell pellet (final volume 100 µL). Subsequently, cells were re-suspended with the use of a pipette, vortexed and kept on ice for 2 min before the separation of the cytosolic and nuclear fractions (5000 g, 3 min, 4 °C). The supernatant (cytosolic fraction) was collected and kept on ice until use. The pellet was washed 3 times with HEPES extraction buffer without NP-40. Nuclei were lysed in buffer containing HEPES (10 mM), NaCl (150 mM), MgCl2 (1.5 mM), EDTA (0.2 mM) supplemented with fresh phosphatase and protease inhibitors, and sonicated for 10 s. The protein content of the cytosolic and nuclear fractions was determined using the Bradford assay. Equal amounts of protein (> 250 μg) were used per reaction in equal volumes of the appropriate HEPES buffer. A small sample (20 µg) of protein was kept for immunoblotting. Master mixtures containing activation reagents and SSP4 (10 μM in ddH2O) were prepared and a volume of no more than 10% of the total volume was added to each sample. All reactions were protected from light. Samples were gently shaken for 60 min at 37 °C in the dark. Thereafter, the samples were centrifuged (16,000g, 15 min, 4 °C) and supernatants recovered for LC-MS/MS or fluorescence measurements. For the quantification of H2Sn production, standard curves were generated using fluorescein and SSP4 in the appropriate SSP4 (10 μM)-containing HEPES buffer.

2.9.3. Assay of H2Sn in isolated tissues

Frozen tissues from different organs were minced and sonicated in RIPA buffer. The extracted proteins were isolated by centrifugation (16,000g, 15 min, 4 °C) and the supernatants were collected and kept at 4 °C. Equal amounts of protein (1 mg) were used per reaction and when necessary, dilution was performed in RIPA buffer. A portion of each sample (50 μg) was kept for immunoblotting. Each sample was then split in two equal parts and SSP4 (10 μM) was added along with the appropriate substrates or inhibitors, all diluted in ddH2O. All reactions were protected from light. After incubation for 60 min (37 °C) the samples were processed as described above. For the quantification of H2Sn production, standard curves for fluorescein and SSP4 were generated in RIPA buffer.

2.9.4. Assay of H2Sn in isolated platelets

Washed human platelets were counted using a Casy cell counter (Omni life science; Bremen, Germany) and were adjusted to 1–2 × 106 per mL. Each sample was split in two equal parts (each 150 µL) and SSP4 (10 µM) was added along with the appropriate substrates or inhibitors (each diluted in ddH2O). All reactions were protected from light. Because the concentrations of inhibitors used in the in vitro studies proved to be toxic to platelets, inhibitor concentrations were decreased by 90% versus Section 2.9.1. Samples were gently shaken for 60 min at 37 °C and then the supernatant was recovered by centrifugation (16,000g, 4 °C, 15 min) and used for LC-MS/MS. The platelet pellets were processed in RIPA buffer for immunoblotting. For quantification of polysulfide production, standard curves of fluorescein and SSP4 were generated in platelet isolation buffer.

2.10. Sample preparation for LC-MS/MS

Samples (50 µL) were supplemented with the internal standard fluorescein amine (Sigma-Aldricht, Darmstadt, Germany) at a final concentration of 500 nM. Spiked samples were added to glass autosampler vials (Macherey-Nagel, Weilmünster, Germany) for LC-MS/MS.

2.11. Instrumentation, LC-MS/MS conditions and parameters

Samples (5 µL) were measured by LC-MS/MS using a 1290 Infinity UHPLC system (Agilent Technologies Deutschland GmbH, Waldbronn, Germany) and a C18 Phenomenex Kinetex (150 × 2.1 mm) column, protected by a Phenomenex C18 guard cartridge. The column oven was heated to 40 °C. HPLC running solvents were: (A): H2O + 0.1% formic acid; (B) acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid. The following gradient was applied: 0–1 min: 80% A, 3–5 min: 10% A, 5.2–7 min 5% A, 7.5–10 min: 80% A, at a constant flow rate of 500 µL/min. MS/MS analysis was done with a 5500 QTrap triple quadrupole mass spectrometer with a TurboV electro spray ionization source (Sciex, Darmstadt, Germany) in positive mode using the following settings: TEM = 250 °C; IS = 5500 V; GS1 = 40 psi; GS2 = 40 psi; CUR = 20 psi; CAD = medium. System control and data analysis were processed by Analyst software 1.6.2 and Multiquant 3.0 (both Sciex, Darmstadt, Germany).

2.12. Fluorescence assay

Samples (50 µL) were added to a white, flat bottomed 96 well plate (Greiner Bio-One, Solingen, Germany). Measurements were performed with a Perkin-Elmer EnVision 2104 Multilabel Reader (Rodgau, Germany) fluorescence detector and evaluated with the Wallac EnVision Manager 1.12 software; emission λ510 nm, excitation λ488 nm. Fluorescence derived from the formation of fluorescein following the reaction of the SSP4 with the positive control Na2S3 was determined.

2.13. Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical evaluation was performed with either Student's t-test, one way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls or Dunnett's multicomparison tests where appropriate. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Assay development and validation

Under physiological conditions (pH 7.4 and 37 °C), less than 20% of the H2S generated in a cell exists on its molecular form and the remainder is largely present in the form of HS- with a small amount of S2- [23]. SSP4 has been proposed to interact selectively with sulfane sulfurs to generate fluorescein [11]. H2S-derived sulfane sulfur species include polysulfides, hydropersulfides and persulfides but for the sake of clarity the sulfane sulfur pool is referred to as “H2Sn” throughout the manuscript.

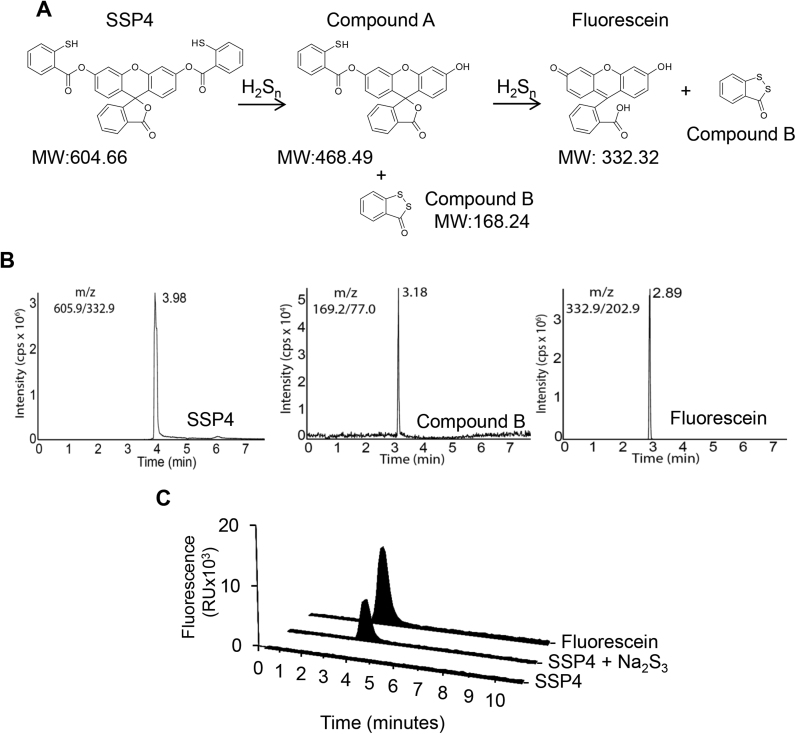

According to H2Sn chemistry the reactions result from the nucleophilic attack of the thiolate residue of SSP4 and sulfane sulfur atoms of H2Sn. SSP4 subtracts two sulfur atoms from H2Sn to form fluorescein and two equivalents of 3H-1,2-benzodithiol-3-one (Compound B) (Fig. 1A). LC-MS/MS chromatograms were created for SSP4, fluorescein and Compound B (Fig. 1B) from authentic standards and the ion source and fragmentation parameters for the MS were optimized (Table 1). Using the standard LC-MS/MS conditions, the retention times of the purified substances were 3.98 min for SSP4, 2.89 min for fluorescein and 3.18 min for Compound B (Fig. 1B). To detect the fluorescence derived from fluorescein, samples were analyzed by HPLC coupled to a fluorescence detector. On its own, SSP4 did not fluoresce but the elution time of the peak generated by authentic fluorescein coincided with that of the peak generated by the reaction of SSP4 with the H2Sn donor, Na2S3 (Fig. 1C). To control for the possible loss of the selective products during the assay procedure, and for normalization purposes, each sample was supplemented with fluorescein amine as an internal standard.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of the molecules detected during the reaction of H2Snwith SSP4. (A) The nucleophilic reaction of H2Sn with SSP4 results in the formation of Compound A and Compound B. Subsequently Compound A reacts further with H2S-derived species to generate fluorescein and a second molecule of Compound B. (B) Representative HPLC-MS/MS spectra for SSP4 (10 μM), fluorescein (10 μΜ), and Compound B (10 µM). Note the different scales on the y axes. (C) Fluorescent signal detected after HPLC of SSP4, fluorescein and the product of the reaction of SSP4 with Na2S3 (10 µM, 30 min).

Table 1.

Mass spectrometry parameters.

| Q1 [m/z] | Q3 [m/z] | ID | DP [V] | EP [V] | CE [V] | CXP [V] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 605.9 | 109.0 | SSP4_1 | 151 | 10 | 109 | 54 |

| 605.9 | 332.9 | SSP4_2 | 151 | 10 | 41 | 22 |

| 605.9 | 334.0 | SSP4_3 | 151 | 10 | 33 | 26 |

| 332.9 | 200.0 | Fluorescein_2 | 231 | 10 | 119 | 12 |

| 332.9 | 202.0 | Fluorescein_3 | 231 | 10 | 75 | 12 |

| 333.0 | 200.1 | Fluorescein_5 | 126 | 10 | 107 | 30 |

| 169.0 | 77.0 | Compound_B_1 | 81 | 10 | 39 | 16 |

| 169.0 | 51.0 | Compound_B_2 | 81 | 10 | 65 | 14 |

| 348 | 200.1 | Fluorescein amine_1 | 81 | 120 | 117 | 14 |

| 348 | 202 | Fluorescein amine_2 | 81 | 120 | 81 | 24 |

DP – declustering potential; EP - entrance potential; CE – collision energy; CXP – collision cell exit potential; SSP4_3 and Fluorescein_3 were used for quantification. The other Fragments served as qualifier; Fluorescein amine served as internal standard.

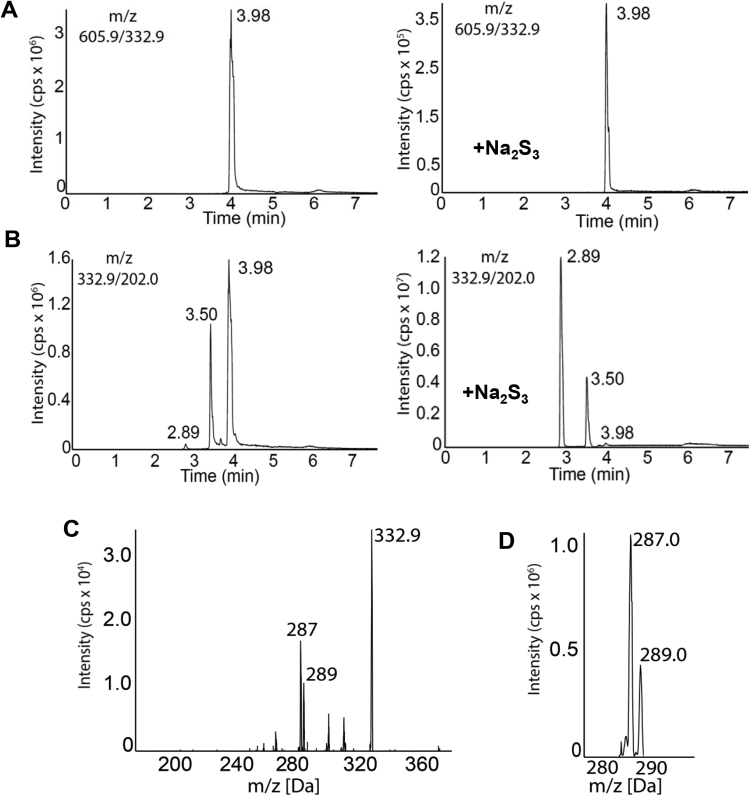

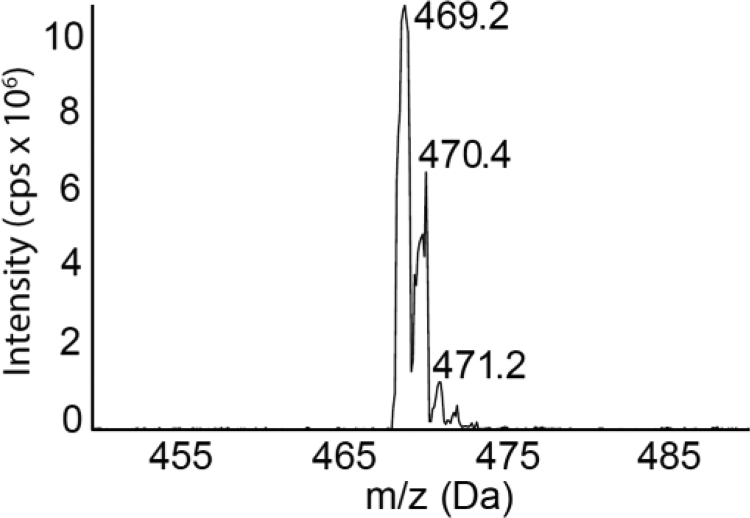

The next step was to more closely analyze the intermediate(s) generated during the reaction of SSP4 with an inorganic H2Sn donor. SSP4 (m/z 605.9, [M+H]+) was recovered from control samples as a single peak (Fig. 2A) with a retention time of 3.98 min, the addition of Na2S3 led to a reduction in peak intensity, indicating the consumption of SSP4 (Fig. 2A). The chromatogram of fluorescein (m/z 332.9, M+) derived from the reaction of SSP4 with Na2S3, showed three peaks. The peak at 2.89 min represents fluorescein as well as the reaction product of SSP4 with Na2S3, the peak at 3.98 min was related to in-source fragmentation of SSP4 and therefore had the same retention time as pure SSP4 (3.98 min). Interestingly, a fluorescein peak at 3.5 min was also detected (Fig. 2B), which probably results from the in-source fragmentation of an unknown compound. To identify the latter, a Q1 scan was performed to distinguish the different masses at this retention time (Supplementary Fig. 1). The scan identified a peak (m/z 469.2 [M+H]+) that was probably an intermediate product (referred to as Compound A; see Fig. 1A). The observed mass (m/z 332.9M+) in the fragmentation pattern of m/z 469.2 (Fig. 2C) mirrored the fragmentation pattern of fluorescein itself (Fig. 2D), indicating that the peak m/z 469.2 was Compound A. Taken together, these data indicate that SSP4 reacts with Na2S3 to generated Compound A and fluorescein. However, the reaction of Na2S3 with SSP4 did not produce equimolar amounts of fluorescein as was previously suggested [11], rather, a more accurate assay of H2S-derived polysulfide levels requires the quantification of both fluorescein and Compound A.

Fig. 2.

Detection of polysulfide-selective spectra after reaction with SSP4. (A) Representative HPLC-MS/MS chromatogram (m/z 605.9) for SSP4 consumption before and after addition of Na2S3 (10 μΜ). (B) Representative HPLC-MS/MS chromatogram (m/z 332.9) for fluorescein (RT 2.89 min) and Compound A (RT 3.5 min) and SSP4 (RT 3.98 min) before and after addition of Na2S3 (10 μM). Note the different scales on the y axes. (C&D) Fragmentation patterns of Compound A (m/z 469.2) observed at RT 3.5 min (C) and fluorescein (m/z 332.9) observed at RT 2.89 min (D).

3.2. Quantification of H2Sn in different conditions

Taking the above considerations into account, H2Sn in biological samples or liberated from chemical donors equals the concentrations of the sum of Compound A and fluorescein or those of Compound B. However, no standard is currently available for Compound A, and Compound B is difficult to detect by LC-MS/MS in most biological samples. Thus, the true concentration of H2S-derived sulfane sulfur moieties generated in the samples tested is a combination of:

-

A.

The unknown equivalent of H2Sn reacting with an unknown partial amount of the SSP4 added to generate 1 equivalent of Compound A and 1 equivalent of Compound B,

-

B.

The unknown equivalent of H2Sn reacting with an unknown amount of the SSP4 added to generate 1 equivalent of fluorescein and 2 equivalents of Compound B.

However, the equivalent amounts of H2Sn reacted to the equivalent of SSP4 are related by a 2/1 ratio (as 2 mol of H2Sn react with 1 mol of SSP4 to generate 1 mol of fluorescein)

Given these conditions, the quantity in mol of the generated H2S n is:

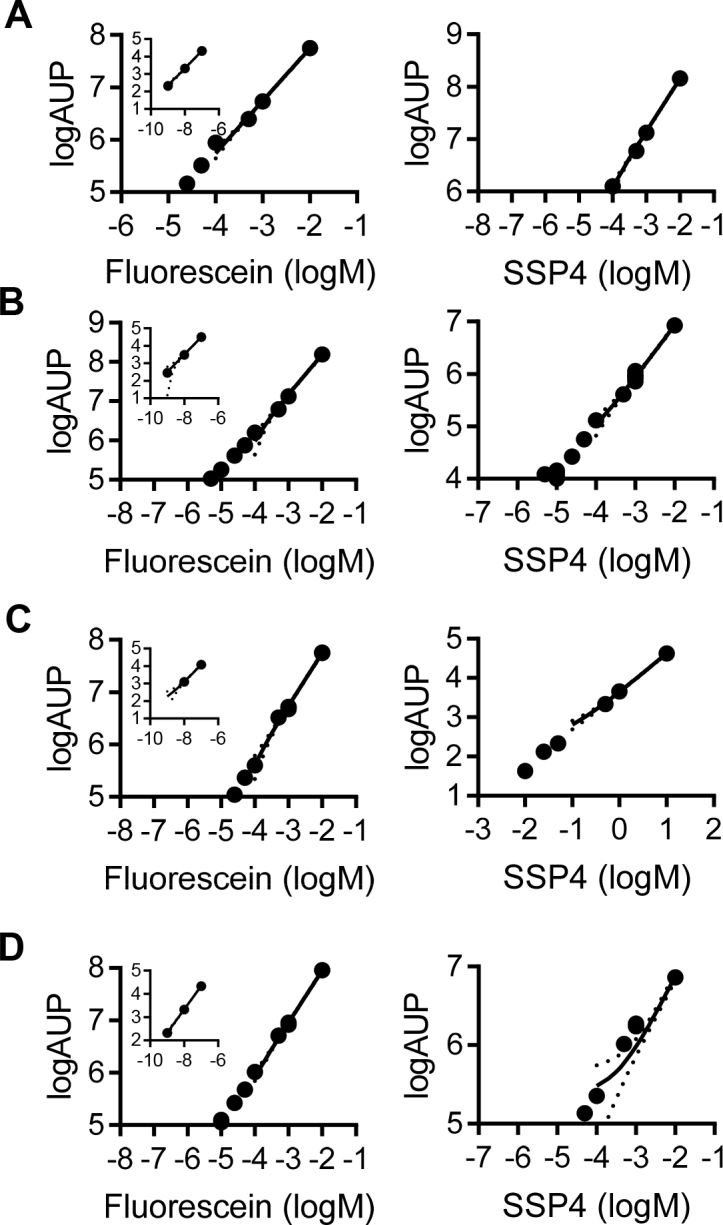

As a consequence, standard curves were generated with pure fluorescein and SSP4 in appropriate assay buffers to quantify the SSP4 remaining after each reaction as well as the fluorescein produced. The standard curves generated showed a linear behavior (Supplementary Fig. 2).

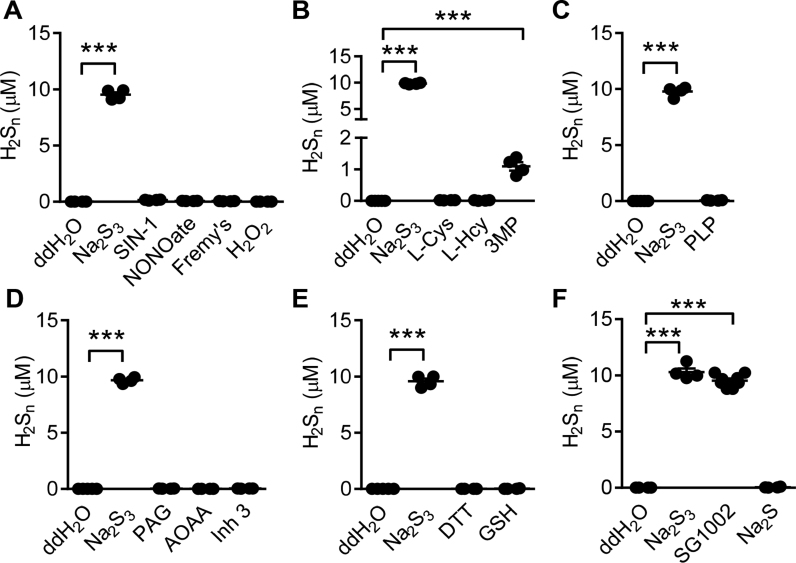

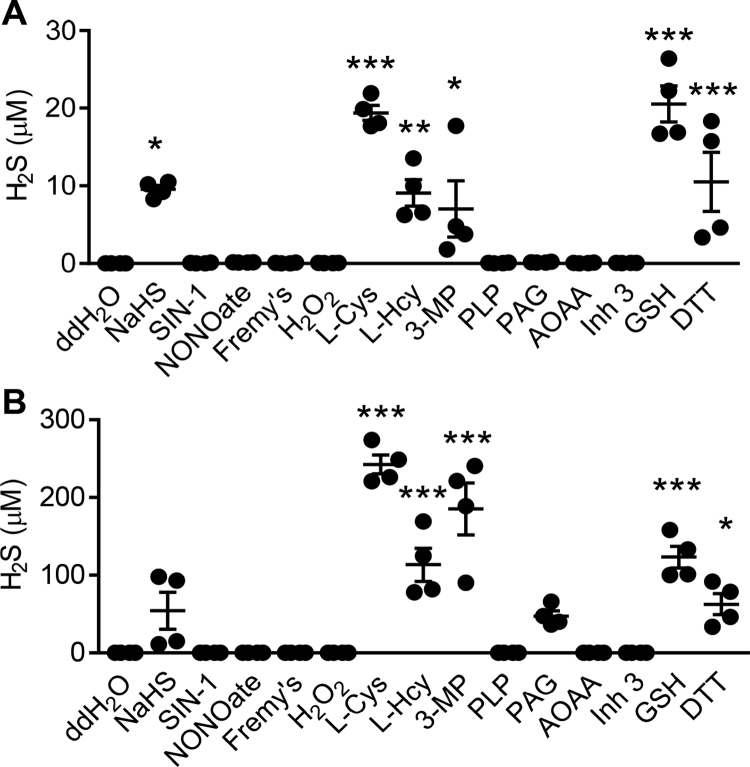

3.3. Characterization of H2Sn specific reaction to SSP4/method selectivity

To determine the specificity of the reaction of SSP4 with H2Sn, the generation of fluorescein and Compound A was determined following the reaction of SSP4 with a NO donor (DeaNONOate), a ONOO- donor (SIN-1), Fremy's salt; which generates nitroxyl radicals [24], and H2O2, and quantified using a standard curve (Fig. 3A). In these experiments fluorescein and Compound A were only generated in the presence of Na2S3 (Supplementary Table 1). On their own, neither L-cysteine nor L-homocysteine, both of which are substrates of the CSE and CBS enzymes, reacted with SSP4 (Fig. 3B). However, the 3MST substrate, 3-mercaptopyruvate, elicited an increase in the reaction product formation which may fit with the previous report that 3-mercaptopyruvate is a non-enzymatic source of H2S in cells [25], [26]. Also, neither the cofactor pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (Fig. 3C), nor the inhibitors PAG, AOAA or Inhibitor 3 (Fig. 3D) elicited the generation of fluorescein and Compound A (Supplementary Table 1). 1,4-Dithiothreitol and glutathione gave no significant increase of fluorescein or Compound A (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Table 1). When the signal generated by Na2S3 was compared with that of other sulfide donors i.e. Na2S and SG1002, (all 10 μM in H2O) similar concentrations of H2Sn were generated only with SG1002, while Na2S failed to increase the signal (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Selectivity of the reaction of SSP4 with potential polysulfide sources. H2Sn produced following the reaction of SSP4 in ddH2O with potential polysulfide sources was determined by LC-MS/MS. (A) Reaction between SSP4 and SIN-1 (100 µM), DeaNONOate (100 μΜ), Fremy's salt (100 µM) or H2O2 (100 μΜ). (B) Reaction between SSP4 and the CSE, CBS and 3MST substrates L-cysteine (L-Cys, 100 μM), L-homocysteine (L-Hcy, 100 μΜ), and 3-mercaptopyruvate (3-MP, 100 μM). (C) Reaction between SSP4 and the co-factor pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP, 10 μΜ). (D) Reaction between SSP4 and the inhibitors PAG (1 mM), AOAA (1 mM) and inhibitor 3 (Inh 3, 100 μΜ). (E) Reaction between SSP4 and the thiol containing compounds 1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT, 100 μΜ) and glutathione (GSH, 100 μΜ). (F) Reaction between SSP4 and the polysulfide donor SG1002 (10 μΜ) and the S2- donor (Na2S, 10 μΜ). In all experiments the polysulfide donor Na2S3 (10 μΜ) was included as a positive control; n = 4–8 per group. ***P < 0.001 (ANOVA + Dunnett's multiple comparison test).

To determine the selectivity and sensitivity of the SSP4-based method versus more widely used approaches proposed to detect H2S and not H2Sn, the samples studied in Fig. 3 were re-analyzed using the methylene blue [21] and AzMC [22] methods. Both of these methods gave a positive signal in the presence of the H2S donor NaHS. However, both of them also demonstrated a cross-reaction (false positive response) with sulfur containing compounds such as L-cysteine, 3-mercaptopyruvate, dithiothreitol and glutathione (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of SSP4 HPLC-MS/MS selectivity to widely used H2S detection methods. H2S production in ddH2O determined using (A) the methylene blue assay and (B) the AzMc fluorescence assay. Experiments were performed in the absence (ddH2O) and presence of SIN-1 (100 µM), DeaNONOate (100 μΜ), Fremy's salt (100 µM), H2O2 (100 μΜ), L-cysteine (L-Cys, 100 μM), L-homocysteine (L-Hcy, 100 μΜ), and 3-mercaptopyruvate (MP, 100 μM), the co-factor pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP, 10 μΜ), PAG (1 mM), AOAA (1 mM), inhibitor 3 (Inh 3, 100 μΜ), glutathione (GSH, 100 μM) and dithiothreitol (DTT, 100 μM), n = 4 per group Quantification was performed by use of a NaHS standard curve. 10 μΜ NaHS is presented as a positive control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus ddH2O (ANOVA + Dunnett's multiple comparison test).

3.4. Intra assay variation and stability

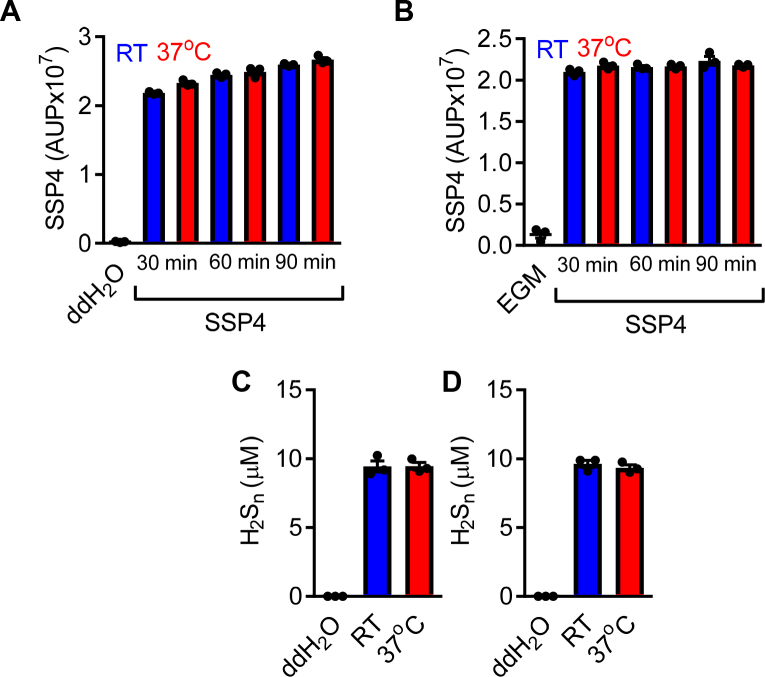

To evaluate the intra assay variation (describing the variation of results within a data set) on both standard curves and unknowns, representative samples prepared in different experimental buffers where measured 6 times. The % intra assay coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated by dividing the standard deviation of the set of measurements by the set mean and multiplying by 100, to monitor the deviation within the same assay. The average of the individual CV is denoted as the intra-assay variation or CVintra and was calculated by combining 3 different individual CVs of known concentrations defined as high, medium and low. Using this approach, variation was less than 10% (Table 2, Supplementary Table 2). To evaluate the stability of the SSP4 over time and with temperature, the SSP4 (10 µM) signal was determined in water as well as in EGM for up to 90 min at room temperature as well as at 37 °C. These experiments revealed that SSP4 was stable (Supplementary Fig. 3A&B). Temperature did not affect the reaction of SSP4 with the polysulfide donor (Supplementary Fig. 3C&D). To assess the stability of the products detected measurements were performed on the same samples on the day of preparation (day 1) as well after 30 or 100 days storage at − 80 °C. Comparable results were obtained in all three cases (compare Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 3, Fig. 5B and Fig. 6B).

Table 2.

Intra assay variability coefficient in the different reaction buffers.

| Reaction buffer variable | H2O | Pelo | RIPA | Platelet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %CVintraFluo | 10,94 | 5,51 | 6,45 | 5,94 |

| %CVintraSSP4 | 9,02 | 10,50 | 6,73 | 10,08 |

| LOD Fluo (M) | 10−8 | 10−9 | 10−7 | 10−9 |

| LOD SSP4 (M) | 10−8 | 10−8 | 10−6 | 10−8 |

Fluo; Fluorescein.

Fig. 5.

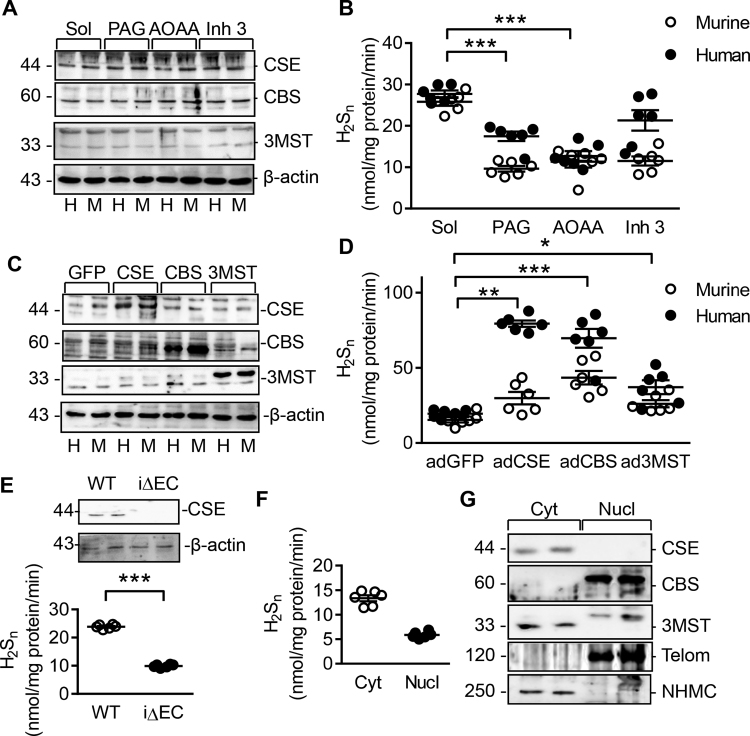

Enzyme expression and polysulfide generation in endothelial cells. (A) CBS, CSE and 3MST levels in cells used for the enzymatic activity assay in panel B; H = human endothelial cells, M = murine endothelial cells. (B) H2Sn levels generated by human (H) and murine (M) endothelial cells in the presence of inhibitors of CSE, CBS and 3MST. (C&D) Human (H) and murine (M) endothelial cells were adenovirally transduced to overexpress GFP, CSE, CBS or 3MST. (C) Western blot showing the effectiveness of overexpression 36 h after transduction. (D) H2Sn generation by the cells shown in panel C in the presence of substrates of CSE, CBS and 3MST enzymes. (E) H2Sn production by endothelial cells isolated from wild-type (WT) and CSEiΔEC (iΔEC) mice. (F) H2Sn levels detected in cytosolic (Cyt) and nuclear (Nucl) fractions isolated from human endothelial cells. (G) Expression of CBS, CSE and 3MST in cytosolic (Cyt) and nuclear (Nucl) fractions from human endothelial cells. Telomerase (Telom) was included as a nuclear marker and non muscle myosin heavy chain (NHMC) as a cytosolic marker. n = 6 experiments per group from 6 different cell batches. ANOVA + Newman-Keuls (B&D), Students t-test (E&F). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 6.

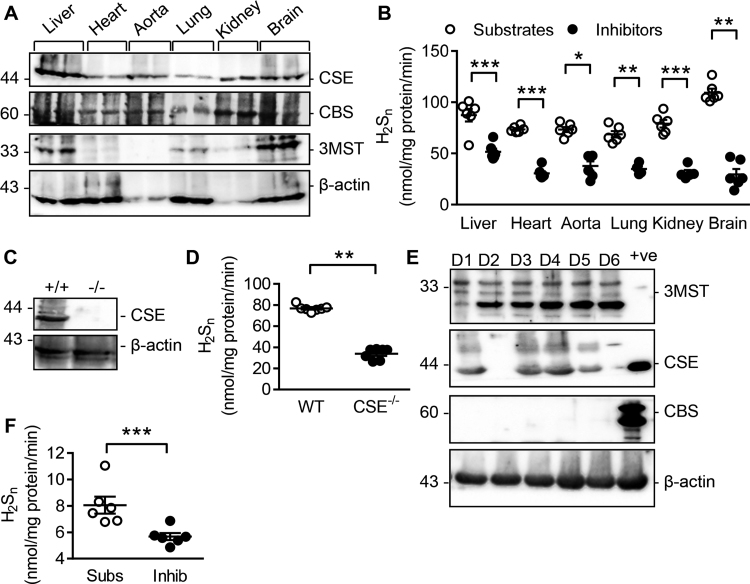

Detection and quantification of endogenous polysulfide levels in murine tissues and human platelets. (A) Levels of CBS, CSE and 3MST in different tissues. (B) Quantification of H2Sn generated by the indicated tissues treated with either substrates of H2S generating enzymes (L-cysteine, L-homocysteine and 3-mercaptopyruvate together with pyridoxal-5′-phosphate), or the inhibitor cocktail consisting of AOAA (1 mM), PAG (1 mM) and inhibitor 3 (Inh 3, 10 µM); n = 6 (Students’ t-test). (C) Expression of CSE in hearts from wild-type(+/+), and CSE-/- mice; similar results were obtained in samples from 4 additional animals in each group. (D) Quantification of H2Sn generated by hearts isolated from wild-type (WT), CSE-/- mice; n = 7–10 per group (ANOVA + Newman-Keuls). (E) Expression of CBS, CSE and 3MST in washed platelets from 6 different donors. HEK cells overexpressing the respective plasmids were included as positive (+ve) controls (Students t-test). (F) Quantification of H2Sn released from platelets in the presence of either H2S generating enzyme substrates (Subs) or the inhibitor cocktail (Inhib); n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

3.5. Application of the assay in cellular, tissue samples and human platelets

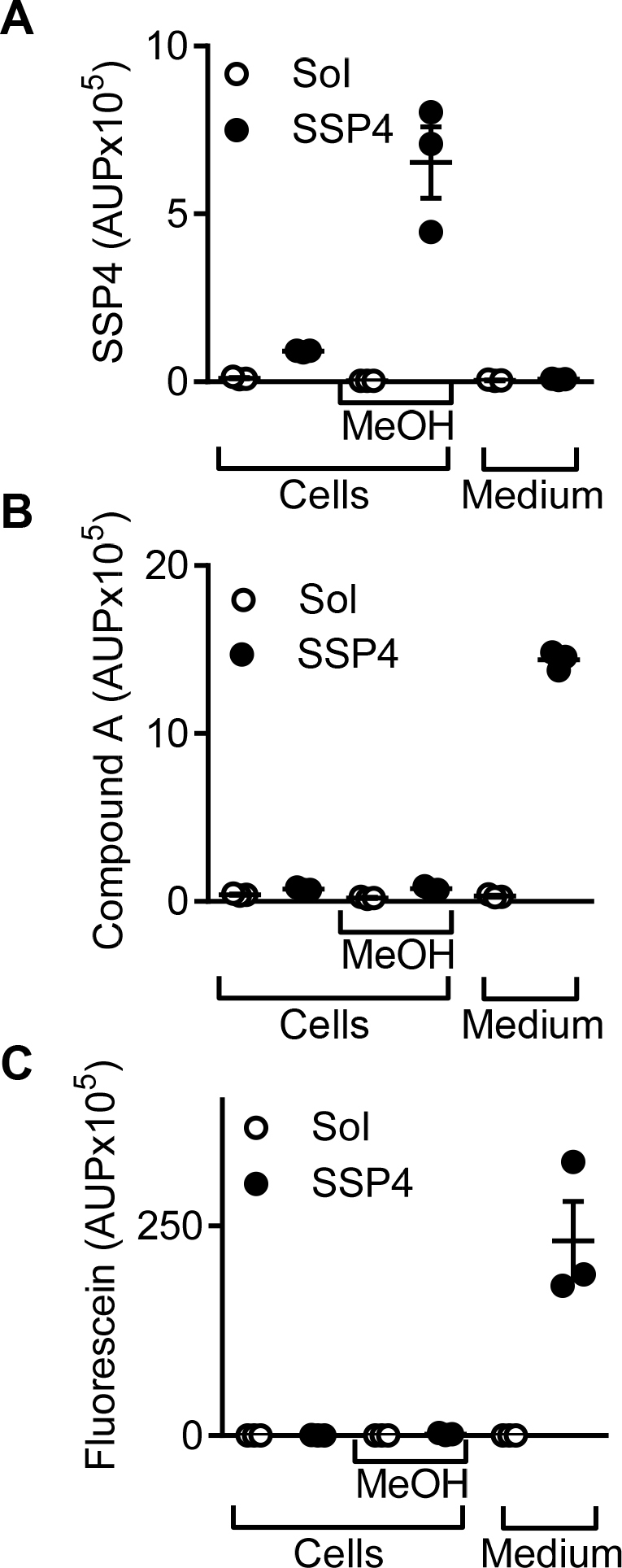

As SSP4 was reported to be cell permeable [11], SSP4 conversion was then determined in intact cells. Unfortunately, no intracellular SSP4, fluorescein or Compound A could be detected in cultured endothelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 5) and no intracellular fluorescence could be detected using a confocal microscope (data not shown). Thus, SPP4 in endothelial cells seems only able to react with the H2S-derived sulfane sulfurs that diffuse across the cell membrane.

To evaluate the usefulness of the SSP4 assay to detect endogenously generated H2S-derived H2Sn in biological samples, measurements were performed using cultured endothelial cells, tissue samples and platelets. The human umbilical vein endothelial cells and murine lung endothelial cells studied expressed all three H2S generating enzymes (Fig. 5A). Both endothelial cell types generated nanomolar concentrations of H2Sn in the absence of any exogenous stimulus (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Table 4). Note however that H2Sn production was assessed in cells incubated in medium lacking phenol red as the latter interfered with the reaction between SG1002 and SSP4 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Given that the initial concentration of polysulfide released into the media was unknown, the recovery of the polysulfides reacting with SSP4 in the culture medium was determined by calculating the percent increase in each 30 min over a 90 min period. This approach revealed that H2Sn recover at 60 min was double that measured at 30 min, giving a recovery rate of 107.3% ± 3.2% (Supplementary Fig. 7). The fact that these values were reproducibly over 100% is most likely attributable to the short delays than were incurred to freeze the samples to stop the reaction.

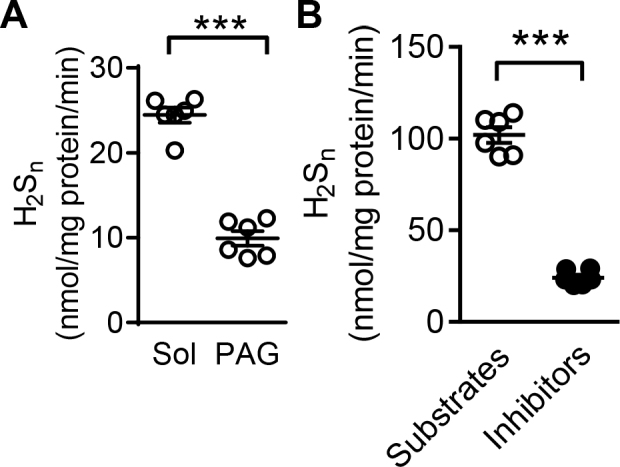

Next, enzyme inhibitors were used to identify which of the H2S-generating enzymes contributed most to the basal production of H2Sn. While the inhibition of CSE using PAG resulted in the largest decrease in H2Sn generation (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Table 4), the simultaneous inhibition of CSE and CBS using AOAA [21] did not further decrease H2Sn production. The inhibition of 3MST with inhibitor 3 [27], only decreased H2Sn production by 10–20%. Taking the opposite approach, the adenoviral-mediated overexpression of all three H2S generating enzymes resulted in significantly elevated H2Sn production (Fig. 5C-D, Supplementary Table 4).

As H2Sn production was detectable in cultured endothelial cells and CSE seemed to be the main source of endothelial cell-derived H2Sn, experiments were repeated using endothelial cells from wild-type and CSEΔEC mice. CSE ablation resulted in a 70% reduction in H2Sn generation (Fig. 5E, Supplementary Table 4), confirming its major contribution to the intracellular H2Sn pool. To evaluate the origin of the endogenous H2Sn in terms of cellular compartments, its production was assessed in the endothelial cell cytosol and nucleus. In the presence of the appropriate co-factors and substrates, H2Sn could be detected in both cellular sub compartments with H2Sn generation by nuclei being approximately 30% of that detected in cytosol (Fig. 5F, Supplementary Table 4). While CSE was exclusively present in the cytosolic fraction, CBS and 3MST were both detected in nuclear fractions (Fig. 5G, Supplementary Table 4).

CSE and CBS were expressed in liver, heart, aorta, lung, kidney and brain samples from wild-type mice while 3MST was only clearly expressed in the liver, lung and brain (Fig. 6A). H2Sn production was detected in snap frozen samples from all of the organs and significantly higher levels were detected in samples containing enzyme substrates (i.e. L-cysteine, L-homocysteine, pyridoxal-5′-phosphate and 3-mercaptopyruvate) than in the samples treated with enzyme inhibitors (Fig. 6B, Supplementary Table 5). Quantification revealed H2Sn levels in the nanomolar range. Experiments were repeated using snap frozen hearts from wild-type and CSE-/- mice (Fig. 6C), and H2Sn production was clearly attenuated in hearts from the latter group (Fig. 6D, Supplementary Table 5). Freshly isolated human platelets only express CSE and 3MST (Fig. 6E), but generated nanomolar concentrations of H2Sn in the presence of L-cysteine, L-homocysteine, pyridoxal-5′-phosphate and 3-mercaptopyruvate (Fig. 6F, Supplementary Table 5).

3.6. Detection of H2Sn by assessing relative fluorescence

Fluorescein and Compound A were generated by the reaction of SSP4 with H2Sn, only one of which is fluorescent. Even though levels of Compound A tended to be higher than that of fluorescein in vitro, the latter could be exploited for the semi-quantitative measurement of H2Sn production from biological samples by evaluating the fluorescence on a plate reader. Interestingly, although the differences in H2Sn detected were comparable among groups, the quantification revealed a more than 3 fold difference using a plate reader versus the LC-MS/MS-based assay (compare Supplementary Fig. 8 with Fig. 6D). However while the accumulation of fluorescein did provide a general indication of H2Sn generation in the heart, the limit of detection was much higher than that of the LC-MS/MS method, and it was not possible to detect H2Sn generation by cultured endothelial cells.

4. Discussion

The results of the current study reveal that monitoring the metabolism of SSP4 and generation of fluorescein in biological samples allows the quantification of H2Sn and can be used to determine the contribution of H2S-generating enzymes to the biological H2Sn pool.

The method described, is highly selective, with less than 10% intra assay variability, gives stable reaction products at different temperatures and has a low limit of detection. Indeed, the assay could be used to detect low levels of H2Sn in biological material and gave the concentration of the H2Sn generated (per mg protein per minute) in the nanomolar range. Moreover, the ablation of CSE in both endothelial cells and heart resulted in a more than 65% reduction in H2Sn levels, confirming a previous report [28] that CSE makes a larger contribution to H2Sn generation in the cardiovascular system than either CBS or 3MST. Finally, a detailed analysis with possible interactors clearly demonstrated the superior sensitivity of detecting the specific reaction products between H2Sn and SSP4 versus the widely used methylene blue and AzMC methods.

The starting point for our investigation was that available methodology failed to quantify the H2S or any H2S-derived moiety generated endogenously in cells and tissues. Part of the problem can be attributed to difficulties in differentiating between the H2S generated enzymatically and the H2S-derived sulfane sulfurs that are almost immediately generated in biological systems. Added to that, false positive signals such as those detected between Methylene Blue and AzMC and sulfur containing molecules, have probably confused the situation somewhat. Several additional factors can influence the accuracy of assays to measure H2S-derived H2Sn generated by cells and tissues. For example, H2S tends to rapidly react with glass and metal, thus, all procedures were carried out in reaction vessels made of polypropylene, which has been shown to be unreactive with H2S products [29].

The H2Sn assay outlined in this study is based on the selective reaction of SSP4 with the H2Sn generated by cells and tissues that is able to transverse cell membranes. H2S rapidly diffuses from cells and biopsied tissue samples and its detection relies on its specific reaction with an exogenously applied probe or indicator versus biological H2S-acceptors, such as protein cysteine residues. HS- bound to cysteine residues could not contribute to the signals evaluated in the present study as the experiments were conducted in the absence of the reducing agent required to release the bound sulfane sulfur. As H2S is generated intracellularly it would be beneficial to develop membrane permeable probes along the lines of the SSP1 and SSP2 compounds [30], that have been reported to detect intracellular sulfane sulfur pools in bioimaging applications. The SSP4 probe is currently the preferred probe for polysulfides or sulfane sulfurs as it has improved sensitivity than SSP1 and SSP2 probes.

Perhaps the only drawback of the method described for widespread use is the fact that it is based on mass spectrometry. As fluorescein is a product of the reaction of SSP4 with H2Sn a simplified method based solely on the generation of fluorescein could be used to determine H2Sn generation using a plate reader. However, the level of detection was much lower and while H2Sn could be detected in tissue lysates it was no longer possible to assess H2S-generating enzyme activity in samples from cultured cells. In addition, the quantification of the H2Sn produced as determined using the plate reader gave a 3 fold lower signal than the LC-MS/MS-based approach. It is also important to mention that different reaction buffers or media can potentially interfere with the detection of H2Sn, particularly phenol red in culture medium markedly interfered with SSP4 product generation. Therefore, calibration curves need to be generated for each experimental buffer used.

Taken together, the method outlined facilitates the quantification of H2Sn in biological samples and is sensitive enough to differentiate the contribution of different H2S-generating enzymes to the H2Sn pool in intact cells and tissue homogenates. Given the quantification of the low continuous production of H2Sn in the nanomolar range, caution should be exerted in interpreting the results of many in vitro and in vivo studies that used exceedingly high concentrations (> 100 µM) of H2S donors to induce alterations in tissue function.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Isabel Winter and Katharina Herbig for expert technical assistance.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the European Society of Cardiology (Basic Research Fellowship 2016 and Research Grant R-2016-054 to S.-I.B.), the Schering Stiftung (Young Investigator Fund for Innovative Research 2017, to S.-I.B) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 815/A16 and SFB 834/B13 to I.F. and Exzellenzcluster 147 "Cardio-Pulmonary Systems").

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.redox.2018.07.016.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Fig. S1.

Q1 scan of SSP4 treated with a polysulfide donor (10 μM), at retention time 3.5 min.

Fig. S2.

Standard curves for fluorescein and SSP4 in different assay conditions. Area under the peak (AUP) for fluorescein (retention time 2.89 min), and SSP4 in (A) ddH2O, (B) Endothelial cell growth media, (C) RIPA buffer and (D) Platelet isolation buffer detected by HPLC-MS/MS; Results were obtained following 3 independent experiments. Dotted lines show the 95% confidence interval.

Fig. S3.

Stability of SSP4 and reaction products in different temperatures. Area under the peak (AUP) of SSP4 (10 μM) after 30 min, 60 min and 90 min in (A) ddH2O and (B) EGM maintained either in room temperature/RT (blue bars) or 37oC (red bars). H2Sn detected in (C) ddH2O and (D) EGM following the reaction of SSP4 with the polysulfide donor Na2S3 after 30 min. n = 3 per group.

Fig. S4.

(A) H2Sn levels generated by murine endothelial cells Repetition of the experiment presented in Fig. 5B in the absence and presence of PAG (1 mM), 30 days after the first measurement with the use of the same samples. (B) Quantification of H2Sn generated by the heart samples presented in Fig. 6B, treated with either substrates of H2S generating enzymes (L-cysteine 100 µM, L-homocysteine 100 µM, and 3MP 100 µM) together with PLP (10 µM), or the inhibitor cocktail consisting of AOAA (1 mM), PAG (1 mM) and inhibitor 3 (Inh 3, 10 µM); n = 6 (Students’ t-test). Measurement was repeated 100 days later to address the stability of the detected products.

Fig. S5.

Lack of SSP4 in cell fractions. Area under the curve for SSP4 (RT 3.89 min; m/z 605.9), Compound A (RT 3.5 min) and fluorescein (RT 2.89 min, for both m/z 332.9 used) from cell fractions or cultured media in the presence and absence of SSP4. n = 3 independent experiments.

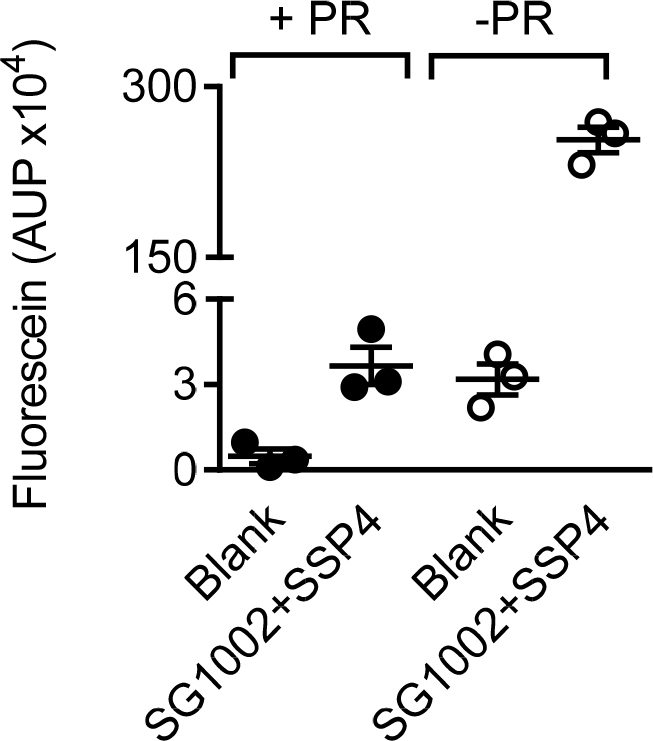

Fig. S6.

Polysulfides are not detectable in the presence of phenol red supplemented media. Comparison of area under the peak (AUP) for fluorescein (RT 2.89 min) in a phenol red supplemented (+PR) and a phenol red free (-PR) endothelial growth factor medium, resulting from the reaction of SSP4 (10 µM) with SG1002 (10 µM). n = 3 experiments from independent cell batches.

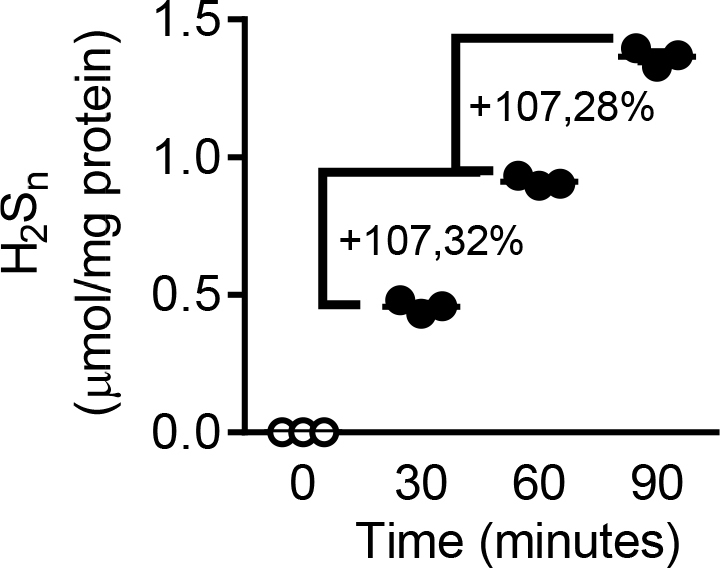

Fig. S7.

Recovery analysis of polysulfides in murine endothelial cells. Amount of endogenous H2Sn generated every 30 min at 37oC from murine endothelial cells in the presence of SSP4 (10 μM). n = 3 independent experiments.

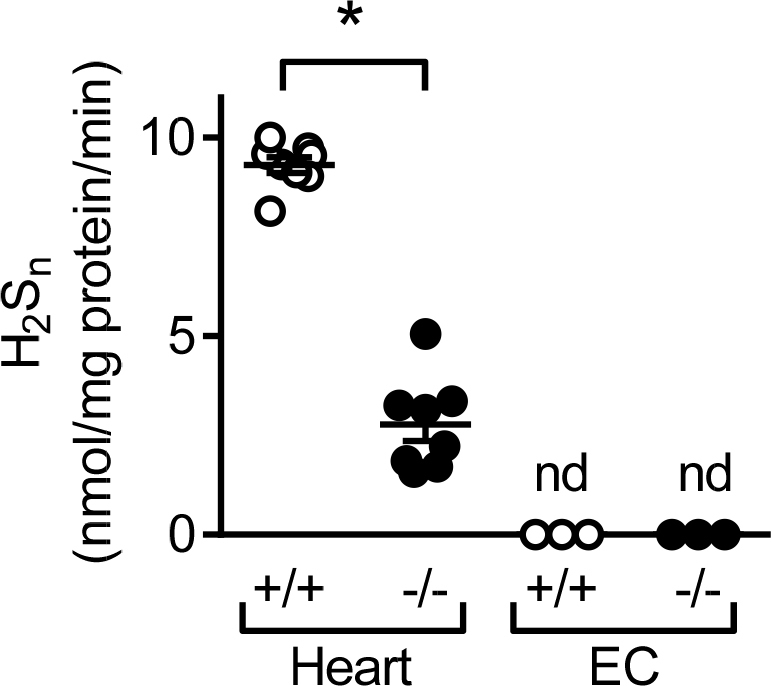

Fig. S8.

Detection of endogenous polysulfide levels using a fluorescence plate reader. Relative quantification of H2Sn generated by hearts (same samples as Fig. 6) and cultured endothelial cells from wild-type (+/+) and CSE-/- (-/-) mice; from n = 7 animals per /group (Student’ t-test). *P < 0.05, * **P < 0.001. nd = not detectable.

References

- 1.Wang R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol. Rev. 2012;92(2):791–896. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shibuya N. A novel pathway for the production of hydrogen sulfide from D-cysteine in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1366. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kabil O., Banerjee R. Enzymology of H2S biogenesis, decay and signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20(5):770–782. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimura H. Physiological roles of hydrogen sulfide and polysulfides. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2015;230:61–81. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18144-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson K.R. Is hydrogen sulfide a circulating "gasotransmitter" in vertebrate blood? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1787(7):856–863. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitvitsky V., Kabil O., Banerjee R. High turnover rates for hydrogen sulfide allow for rapid regulation of its tissue concentrations. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012;17(1):22–31. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du Z. Quantitative monitoring and visualization of hydrogen sulfide in vivo using a luminescent probe based on a Ruthenium(II) complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018;57(15):3999–4004. doi: 10.1002/anie.201800540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takano Y., Shimamoto K., Hanaoka K. Chemical tools for the study of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and sulfane sulfur and their applications to biological studies. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2016;58(1):7–15. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.15-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadav P.K. Biosynthesis and reactivity of cysteine persulfides in signaling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138(1):289–299. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi N. Reactive sulfur species regulate tRNA methylthiolation and contribute to insulin secretion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(1):435–445. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura Y. Identification of H2S3 and H2S produced by 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase in the brain. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14774. doi: 10.1038/srep14774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Syhr K.M.J. The H2S-producing enzyme CSE is dispensable for the processing of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Brain Res. 2015;1624:380–389. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monvoisin A. VE-cadherin-CreERT2 transgenic mouse: a model for inducible recombination in the endothelium. Dev. Dyn. 2006;235(12):3413–3422. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bibli S.I. Cystathionine gamma lyase sulfhydrates the RNA binding protein HuR to preserve endothelial cell function and delay atherogenesis. Circulation. 2018 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu J. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase prevents diabetic retinopathy. Nature. 2017;552(7684):248–252. doi: 10.1038/nature25013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming I. Role of PECAM-1 in the shear-stress-induced activation of Akt and the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 18):4103–4111. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coletta C. Regulation of vascular tone, angiogenesis and cellular bioenergetics by the 3-Mercaptopyruvate Sulfurtransferase/H2S pathway: functional impairment by hyperglycemia and restoration by DL-alpha-Lipoic acid. Mol. Med. 2015;21:1–14. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2015.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coletta C. Hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide are mutually dependent in the regulation of angiogenesis and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109(23):9161–9166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202916109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bucci M. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous inhibitor of phosphodiesterase activity. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30(10):1998–2004. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.209783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elgheznawy A. Dicer cleavage by calpain determines platelet microRNA levels and function in diabetes. Circ. Res. 2015;117(2):157–165. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asimakopoulou A. Selectivity of commonly used pharmacological inhibitors for cystathionine beta synthase (CBS) and cystathionine gamma lyase (CSE) Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013;169(4):922–932. doi: 10.1111/bph.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Druzhyna N. Screening of a composite library of clinically used drugs and well-characterized pharmacological compounds for cystathionine beta-synthase inhibition identifies benserazide as a drug potentially suitable for repurposing for the experimental therapy of colon cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2016;113:18–37. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.08.016. (Pt A) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes M.N., Centelles M.N., Moore K.P. Making and working with hydrogen sulfide: the chemistry and generation of hydrogen sulfide in vitro and its measurement in vivo: a review. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47(10):1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zielonka J. Mechanistic similarities between oxidation of hydroethidine by Fremy's salt and superoxide: stopped-flow optical and EPR studies. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005;39(7):853–863. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shibuya N. 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase produces hydrogen sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur in the brain. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11(4):703–714. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitidieri E. Mercaptopyruvate acts as endogenous vasodilator independently of 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase activity. Nitric Oxide. 2018;75:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanaoka K. Discovery and mechanistic characterization of selective inhibitors of H2S-producing enzyme: 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3MST) Targeting Active-site Cysteine Persulfide. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:40227. doi: 10.1038/srep40227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan S. Hydrogen sulfide metabolism regulates endothelial solute barrier function. Redox Biol. 2016;9:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levitt M.D. Detoxification of hydrogen sulfide and methanethiol in the cecal mucosa. J. Clin. Investig. 1999;104(8):1107–1114. doi: 10.1172/JCI7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen W. New fluorescent probes for sulfane sulfurs and the application in bioimaging. Chem. Sci. 2013;4(7):2892–2896. doi: 10.1039/C3SC50754H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material