Abstract

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a disorder of increasing prevalence worldwide causing clinical symptoms of vomiting, failure to thrive, and dysphagia and complications of esophageal remodeling with strictures and food impactions. Molecular profiling demonstrates EoE to be an eosinophil predominant disorder with a Th2 cytokine profile reminiscent of other allergic diseases such as asthma, allergic, rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis. Environmental antigens in the form of foods and aeroallergens induce eosinophil, basophil, mast cell, and T cell infiltration. Pathogenesis depends on local epithelial immune activation with production of thymic stromal lymphopoeitin (TSLP) and eotaxin-3. Complications mirror asthmatic airways pathogenesis with increases in subepithelial collagen deposition, angiogenesis, and smooth muscle hypertrophy. The removal of instigating antigens, especially foods, causes disease resolution in >50% of adults and children. The prevalence of concurrent atopic disorders in patients with EoE and the need to control antigen-specific Th2 inflammation underscore the importance of testing for allergens and treating the entire atopic individual to control the potential interplay between organ specific allergic responses.

Keywords: Esophagitis, Food allergy, Allergic rhinitis, Antigens, Allergy testing

Introduction

EoE was first demonstrated to exist as a disease entity in atopic males in the late 1970s.1, 2 Since then, prevalence rates in adults and children have increased significantly to up to 1 in 1000.3 The concept of EoE as a food antigen triggered disorder was based initially on the observation of eosinophils characteristic of allergic diseases in combination with the presence of concurrent asthma in the first patient case reports. Further substantiation of the hypothesis came from the finding that, in children, elemental formula, but not acid blockade with H2 blockers, caused histologic EoE disease remission.4 Since that time, specific antigen elimination diets have demonstrated utility in U.S. and European EoE populations.5, 6 In addition, the onset of EoE during oral immunotherapy for foods and the sustained antigen sensitization to EoE triggering foods such as egg and milk underscore the importance of T cell mediated hypersensitivity.7, 8 Additional data has demonstrated that the presence of IgE sensitization to pollens and indoor aeroallergens can trigger EoE and/or may impact on therapeutic effectiveness.9, 10

The pathogenesis of EoE aligns with other atopic disorders such as asthma and eczema. Esophageal epithelial damage induced by acid and antigens invokes a Th2 immune response with production of TSLP and eotaxin-3 with subsequent influx of eosinophils, mucosal tryptase positive mast cells and basophils, innate lymphoid cells, and adaptive B and T lymphocytes (see other reviews in this issue).11–14 Chronic, unbridled Th2 inflammation causes epithelial and subepithial remodeling with loss of barrier function, fibrosis, angiogenesis, and smooth muscle hypertrophy.15, 16 Together these molecular events cause complications of esophageal rigidity and dysmotility with clinical symptoms of vomiting, dysphagia, food impactions, and strictures. Whether antigen avoidance of foods or aeroallergens can control the natural history to strictures is not currently clear but other interventions such as topical corticosteroids can decrease the rate of complications.17–20

Herein, we review the current understanding of the role of allergens in provoking a Th2 mediated immune response in the esophagus. We further discuss the current state of allergy testing for EoE patients, the importance of treating the whole atopic individual as opposed to utilizing an isolated EoE therapy in a patient with concurrent allergic diseases, and the future directions for elucidating the role of allergens in EoE.

Food antigens

Food antigens have long been indicated as a trigger in EoE. The first descriptions of food elimination to treat EoE by Kelly et al showed that complete removal of dietary antigens using elemental formula led to resolution of symptoms and normalization of esophageal eosinophilia.4 Resolution of symptoms and eosinophils occur in both adults21 and children22 within 4 weeks of treatment with elemental diet. The current data demonstrate that the rate of disease resolution with an elemental diet is over 90% and the rate with empiric or allergy testing based testing can both reach nearly 80%, indicating that most EoE is due to food allergens.22, 23 The removal and subsequent addition of foods leading to EoE resolution and recurrence fulfills Koch’s postulate that food antigens cause EoE.24–26 The penetration of antigens into the esophageal mucosa has been recently demonstrated for gliadin, supporting the potential for local antigen uptake, processing, and presentation in the esophagus.27

Multiple studies have examined and tried to identify most common foods that cause EoE. There appear to be some geographic and age differences. In U.S. children, milk, egg and wheat are the most common while in adults, milk and wheat are the most common (Table 1).5, 23, 26, 28–32 Soy and other legumes are allergens that are more common in Spain than in the US.6, 33, 34 Interestingly, fish, tree nuts and shellfish infrequently cause EoE, yet they are among the “top 8 foods” in most studies examining IgE food allergies.35 Overall in the various studies throughout the world, milk is the most common allergen causing disease in about 2/3 of patients followed by egg and wheat in another ¼ of the patients. Although milk is the most common antigenic trigger for EoE, EoE is also triggered in many patients by other foods. About 30–50% have one food causing disease, followed by 30% having two and the remaining 30% having 3 or more foods causing EoE.5, 6, 23, 31

Table 1.

Most Common Foods in Eosinophilic Esophagitis

| Food Study | n | Pediatric/Adult | Milk | Egg | Wheat | Peanut/tree nuts | Soy/Legumes | Fish/Shellfish |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gonsalves et al29 | 20 | Adult | 50% | 5% | 60% | 10% | 10% | |

| Kagalwalla et al30 | 36 | Pediatric | 74% | 17% | 26% | 6% | 10% | |

| Lucendo et al34 | 42 | Adult | 62% | 26% | 28.6%* | 16.7% | 23.8% | 19% |

| Henderson et al31 | 26 | Pediatric | 65% | 40% | 37% | |||

| Spergel et al23 | 319 | Pediatric | 66% | 24.5% | 22.6% | 5% | 0% | |

| Molina-Infante33 | 28 | Adult | 50% | 36% | 31%* | 18% | ||

| Rodriquez-Sanchez44 | 46 | Adult | 64% | 21% | 28% | 7% | ||

| Wolf et al32 | 11 | Adult | 44% | 44% | 22% | 11% | 11% | 11% |

| Molina-Infante6 | 64 | Adult | 81% | 15% | 43%* | 1% | 9% | 6% |

| Kagalwalla et al5 | 78 | Pediatric | 85% | 35% | 33% | 19% | ||

| Kruszewski et al52 | 20 | Pediatric | 64% | |||||

| Total of 702 patients | Average | 66% | 24% | 27% | 4% | 12% | 2% | |

All gluten containing foods

Testing modalities for EoE triggering foods

Several investigators have examined testing methods for identifying food allergies in EoE by using either percutaneous skin testing23, 31, 36–39 or serum specific IgE.40–43 Alternative methods for measuring food specific IgE including basophil activation test (BAT), Immuno Solid Phase Allergen CHIP (ISAC) have been studied. Potential methods for testing non-IgE methods include IgG4 or atopy patch testing. Retrospective studies of empiric food elimination that subsequently examined specific IgE have shown a varying range of success ranging from 8 to 53%. In general, specific IgE testing is better in children compared to adults. A few retrospective studies have compared allergy testing based diet to empiric elimination diet.23, 31 In adults, specific IgE based elimination diets showed resolution in 73% of patients compared to 53% for six-food elimination diet, a difference that was not statically significant.44 A recent study documented the use of intraesopahgeal injection of food antigen that caused both an immediate and delayed reaction in 5 of 8 EoE subjects tested. However, none of the “positive” antigens were used in dietary management nor was the presence of IgE to these antigens verified.45 The clear documentation of systemic reactions when food antigens are given subcutaneously, the potential for anaphylaxis even to aeroallergens upon ingestion, and the local esophageal response of “complete luminal obstruction” underscore the importance of utilizing caution when techniques such as intraesophageal testing are considered.

Studies have also examined the use of component testing with ISAC test for serum IgE to specific allergen components.42, 46, 47 Erwin et al, found more positive components to milk (Bos d4 or Bos d5) compared to specific IgE or skin prick tests in their population, suggesting increased sensitivity of milk component testing.42 However, these proteins are minor allergen components of milk protein were found at low serum levels, and did not correlate with symptoms or biopsies.48 A separate study demonstrated that food elimination based on ISAC testing did not show any improvement in esophageal eosinophilia.46 Currently, the general conclusion from the literature demonstrate that although ISAC testing or component testing fo foods show increase sensitization, the clinical significance and utility is unclear.42, 43, 48

In general isolated testing for IgE mediated allergy has been largely inadequate for determining EoE-triggering antigens. Philpott et al examined the use of 5 different testing modalities for identifying foods that contribute to EoE in their cohort from Australia.49 They found neither basophil activation test, skin testing, specific IgE, nor allergen-specific IgG4 correlated with improvement with esophageal biopsies in patients responding to six food elimination. The overall success rate for IgE testing for identifying the right food was 36%.

Empiric elimination diets usually avoid the six most common allergenic food groups based on the top 8 foods causing IgE mediated food allergy (milk, egg, soy, wheat, fish/shellfish, peanut/tree nuts). Kagalwalla et al found about 60% improvement in esophageal biopsies in the original six food elimination study in pediatric population.30 Similar efficacy was found in adult studies.26, 29 Recent studies have looked at various two, four and six food elimination diets in prospective manner.5, 6, 33 It is important to remember when looking at these diet studies to carefully examine what is being eliminated. For example, sometimes “wheat free” can be all gluten or gluten-like foods including oat as opposed just wheat.50 Similarly, “soy” can be all legumes or, in other studies, it is strictly just soy. In Kagalwalla’s multi-center study of 78 pediatric patients, they had 60% response rate with a simple 4 food elimination of removing milk, wheat, soy and egg.5 Similarly, a study by Molina-Infante found 53% of subjects responded to a two food group elimination (milk and gluten). The 47% that did not respond to this 2 food group diet were switched to 4 food group elimination diet (milk, gluten, egg and legumes with soy) with 60% response rate; and the non-responders were switched to six-food group elimination diet (milk, gluten, egg, legume-soy, fish, shellfish, peanut and tree nuts) with 79% response rate.6 Together, studies (Table 1) have shown that milk is the most common food that causes EoE. In fact, in milk elimination only studies, the rate of success has been around 65%.51, 52

Alternative approaches for identifying the causative food have included both IgG4 and atopy patch testing. Clayton and Gleich first identified elevated levels of IgG4 in esophageal biopsies, which has been confirmed by others.41, 53, 54 Wright found that IgG4 was elevated in the esophagus of active EoE compared to controlled EoE.55 In addition, recent work by Erwin and Platts-Mills found that IgG4 was elevated in the sera about 100x higher in EoE than in control patients.54 But, they did not examine if there was any correlation with symptoms or resolutions of esophageal eosinophilia54 and using IgG4 as a marker of causative foods has not been revealing to date.49 Currently, it is clear that IgG4 is elevated in EoE, but its role as a pathogenic marker versus an epiphenomenon is unclear. It is interesting to note that IgG4 can cause fibrotic disease but it remains unclear if IgG4 is playing a causative role in EoE complications.

Despite IgE not having a major role in detecting foods causing EoE (see review-56), pediatric patients with IgE mediated allergy to foods are 100 times more likely to develop EoE compared to general public.36 This high correlation indicates that these patients are atopic and their allergic diseases share common mechanistic pathways that involve cytokines such as IL-13, a master regulator of EoE.57 Genetics studies have indicated that Th2 genes including TSLP, eotaxin, STAT-6 are genetic risks for disease.13, 58 Furthermore, Th2 cytokines predominate when examined in the esophageal biopsies31, 59–62. Work by the Rothenberg group has identified a unique molecular signature to active EoE in esophageal biopsies that encompasses many Th2 genes.60 In murine models, expression of IL13 can mimic the molecular phenotype of the disease.63 Recently, Spergel and Cianferoni have identified activated Th2 cells with CD154+IL5+ phenotype in the peripheral blood of active EoE patients but not in the control atopic patients or inactive EoE patients. Further, these peripheral T cells can be stimulated by milk antigens in milk-induced EoE patients but not in control patients.64 These studies indicate that EoE is Th2 antigen driven disease with activation of Th2 cytokines in both the peripheral blood and local tissue.

Since EoE is Th2 disease, examination of foods by patch testing would make logical sense. Atopy patch testing was originally used to detect foods in atopic dermatitis and was found to be particularly useful for patients with delayed gastrointestinal symptoms.65 In EoE studies using atopy patch testing, triggering foods were confirmed as pathogenic when biopsies normalized after removal of the food and/or if appearance of esophageal eosinophilia occurred after addition of the identified food.23, 66 Retrospective studies found that atopy patch testing was able to detect the correct food trigger approximately 50% of the time and had a high negative predictive value of nearly 90% except for milk.24, 66

Comparison of the success rates of allergy testing-based (atopy patch test and skin test) versus empiric elimination diets in retrospective analyses done by two independent centers found similar rates between these two interventions.23, 31 A large study of EoE patients done at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia found a 52% response rate using empiric elimination of milk, egg, wheat and soy which was identical to the success rate of combined atopy patch test and skin test.23 When milk was empirically eliminated in addition to positive foods found on skin and atopy patch testing, the success rate approached 75%. One potential advantage of utilizing an allergy testing based diet in children is the elimination of one fewer food on average as compared with an empiric elimination diet. However, disadvantages of the allergy testing based diet include the time and costs required for additional testing.

Aeroallergens as antigens in EoE

Animal models were the first to document a close immunologic link between the airway and the esophagus. Intranasal instillation of aeroallergens antigens including dust mite, Aspergillus fumigatus, and cockroach causes the onset of experimental EoE.67 In addition, epicutaneous sensitization can drive EoE in animal models.68 Instillation of food antigens such as peanut intranasally also induces esophageal eosinophilia, a process that appears dependent on the proximity of the shared lymph node chain between the trachea and esophagus and on the presence of iNKT cells.69

An initial case report documented aeroallergens as a trigger for EoE in an elemental formula resistant EoE subject with spontaneous disease remission and recurrence during the pollen season.22, 70 A single case series of adults demonstrated new onset EoE following a high load of exposure to environmental aeroallergens including dust mites, pollen, and mold. However, allergic sensitization to the triggering antigen was only demonstrated in one patient (the other 2 were not tested).71

A number of studies have demonstrated that EoE diagnoses can have seasonality with increased esophageal eosinophilia occurring during the spring and summer as compared with the winter months.72–76 Indeed, EoE exacerbations with recurrent food bolus impactions can also be linked to the pollen season.77 However, only one study to date has demonstrated the presence of increased esophageal eosinophilia during a pollen season with proven relevance to the patient, that is, the patient’s EoE exacerbation timing matched their pattern of aeroallergen sensitization. Of 1180 children with EoE at a single institution, 20% of those suspected to have a pollen trigger showed biopsy proven esophageal eosinophilic exacerbations that occurred during a pollen season for which they had specific pollen sensitization. Of these patients, 84% had allergic rhinitis, and 75% had asthma.9

Further support for the role of aeroallergens in EoE is the finding that sublingual immunotherapy for aeroallergens can drive esophageal eosinophilia. The first case report documented initiation of EoE following 4 weeks of sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) with hazelnut, birch and alder and EoE resolution after 4 weeks of SLIT discontinuation.78 A similar case was recently reported in a child who was PPI-resistant but responsive to discontinuation of SLIT.79 Since serial rounds of in vitro differentiation in the presence of antigen drives CD4+/IL-5+ cells in vitro, it is possible that aeroallergen-specific T cells develop during EoE pathogenesis due to chronic local aeroallergen and antigen exposure.80

Oral Allergy Syndrome in EoE

Clinically symptomatic pollen food cross reactivity occurs in patients with allergic rhinitis at a rate of approximately 7–8%. By contrast, 50% of EoE patients studied concurrently at 2 referral centers had symptomatic oral allergy syndrome using a standardized questionnaire. Interestingly, although >90% had aeroallergen sensitization, only half had symptoms of allergic rhinitis, suggesting that aeroallergens may be equivalently likely to cause nasal or oral allergy symptoms in EoE patients.81 Adult studies have documented the presence of cross-reacting food-pollen antigens, specifically PR-10 and profilins with of oral allergy syndrome in 30% but the clinical implication of these sensitizations for EoE management remains unclear.47, 82 It is possible that sensitization to food pollen cross-reacting antigens associates with dysphagia to specific foods such as bread (profilins and PR10) and apple (PR10).82 While 39% of subjects in one study were sensitized to PR-10 proteins in multiple foods (hazelnut, apple, peach, peanut, soy, kiwi, and celery), 40% of adults were sensitized to profilins in another smaller study.78, 82 A new study demonstrated that 88% of EoE subjects in Spanish population had sensitizations detected on component-resolved diagnosis (CRD). The majority of the allergens were grasses and/or lipid transfer proteins from mugwort, peach, hazel, and walnut. The investigators utilized the CRD panel to build elimination diets and/or allergen immunotherapy with high success rates (78%). Follow up occurred for 3 years and in this period >75% of subjects were disease free.83 As such, antigen resolution by finer techniques such as component testing for food-pollen cross reactivity may be useful when creating antigen avoidance regimens.

Potential Prognostic Features of Allergic Sensitization

Data from one study suggests that food sensitization may associate with more severe histologic disease in the context of a promoter single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at −509 of the TGFβ1 promoter. Children with genotype TT had increased numbers of esophageal TGFβ1 positive cells as compared with children who were genotype CC or CT at the TGF1 SNP −509.18, 84 While there were increased numbers of mast cells in EoE children of TT genotype, there were not increased numbers of eosinophils. The difference in the numbers of tryptase and TGFβ1 positive cells was more pronounced in children who had TT genotype and concurrent food sensitization to milk, wheat, egg and/or soy. Among TT genotype, children who were food sensitized had higher fibrosis scores.84 These data suggest a gene-environment pathway involving food-specific IgE expressing mast cells.

Recent work by Fahey on genotype-phenotype interactions has shown that homozygosity or heterozygosity at the risk allele for TSLP variants is associated with the presence of 3 or more EoE food triggers.85 These data suggest that the risk allele at TSLP may predispose to more EoE-relevant food antigens and perhaps suggest a more severe disease course. Genetic changes in the the TGFβ1 signaling pathway that cause connective tissue disorders such as Loeys-Dietz and Marfan’s syndromes can also associate with EoE.86, 87 Subjects with Loeys-Dietz have increased rates of IgE-mediated food allergy and animal models can demonstrate spontaneous EoE, underscoring the potential importance of both IgE and TGFβ1 in EoE. It will be interesting to understand if subjects with connective tissue diseases have altered response rates to usual EoE-directed therapies. Together, these genetic studies lend preliminary insight into a potential link between food allergy and EoE severity.

IgE sensitization to candida has been shown to occur in 16–43% of EoE adults studied in Europe.82, 88 Active EoE was associated with decreased barrier protein expression and decreased cathelicidin even with topical corticosteroid treatment, leading the authors to postulate that TCS therapy may lead to decreased innate immunity, potential candida colonization, and subsequent increased IgE sensitization to Candida.88 However, as compared to the high rates of IgE sensitization, the rates of candidal esophagitis are lower and yeast/hyphae are not detected regularly on biopsies suggesting that the presence of serum candida IgE may be non-specific to EoE. It is also possible that the presence of IgE sensitization to Candida decreases the rate of steroid responsivity.

Aeroallergen sensitization can decrease the success of EoE-directed therapy. In subjects who initially respond to high dose PPI, long-term response is more likely to be lost if there is concurrent allergic rhinitis.89 In children with sensitization to aeroallergens such as cockroach and molds, there was a tendency to have non-response to EoE-directed therapy.10 These findings implicate the importance of environmental antigen avoidance for successful EoE therapy. In addition, it is possible that in EoE, like in asthma, sensitization to aeroallergens can predict lack of EoE resolution.

Modulation of the immune system towards aeroallergen tolerance may relieve EoE. Although such studies are clinically challenging to complete in a prospective, controlled fashion, there has been one case of EoE responding to subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT). A young child with EoE not responsive to PPI or high dose fluticasone, was found to be dust mite sensitive. He was placed on 2-year course of SCIT to dust mite. After the 2-year course, the repeat biopsy was normal off PPI and swallowed steroids.90 Further studies to understand if non-oral methods of aeroallergen immunotherapy could be successful as isolated or add-on therapy for EoE remain to be complete.

Discussion

In summary, there are multiple lines of evidence demonstrating that EoE is an allergic disorder. These data include the presence of antigen specific cells such as milk-specific lymphoid cells and recent data demonstrating detection of antigens such as gliadin and pollen tube callose in the esophagus.27, 64, 91 The ability to treat EoE with antigen elimination for foods and/or pollens and/or cross reacting food-pollens underscores the importance of specific antigens. Triggering damage could include currently unappreciated adjuvants as occurs with diesel exhaust in allergic rhinitis and/or an interplay between acid and antigens.89 Indeed acid can alter epitopes, potentially predispose to food allergy, and disrupt epithelial barriers thereby allowing the transit of food and aeroallergen particles locally into the esophagus. Systemic and other local cues such as those derived from cells immigrating and emigrating from shared lymph nodes chains (tracheal and gastric) likely also plays a role in triggering an antigen-specific response in the esophagus.

Like other allergic disorders, it is likely that EoE is influenced by concurrent atopy. In addition, it is possible that there are common triggers for EoE and concurrent allergic diatheses, for example, viral illnesses could trigger both asthma and EoE. Some of the clearest examples of this are EoE exacerbation during the pollen season or instigation by an aeroallergen that also exacerbates clinical allergic rhinitis.9 Data supporting altered therapeutic response to topical corticosteroids or PPI due to aeroallergen sensitization also supports the importance of allergy testing and avoidance of potentially relevant antigens.10 Indeed, it has been noted that most subjects treated with topical corticosteroids have eventual loss of control of complete histologic normality and recurrence of lower levels of eosinophilia despite continued therapy.92 Whether this reflects a shift in the balance between therapy-induced disease control and allergic sensitization remains to be understood. Similar to asthma where dust mite avoidance can induce complete control of airways hyperreactivity, it is possible that complete EoE resolution requires avoidance of all relevant antigens. This may include foods and even food-pollen antigens in some subjects.

EoE is a chronic disease in the majority of subjects and long term avoidance of food antigens is likely required. In a large single center study, only 9 of 1812 (0.5%) pediatric patients tolerated an unrestricted diet following food elimination.93 Factors that predispose to disease retention versus resolution remain unclear but may well include the presence of antigen sensitization. Although it did not alter response rates, children with concurrent asthma and EoE had higher esophageal eosinophil counts than those without asthma.17 In addition, the ability of immunomodulation early in the disease course to modify the natural history towards chronic EoE is not clear but would of interest to study. The blockade of Th2 cytokines such as IL-13 may be of utility in this regard.94

In conclusion, EoE is an antigen driven Th2 disease in which allergen avoidance can function as a single or adjuvant therapy for disease control. The identification of specific subsets of antigen-specific innate and adaptive lymphocytes and novel ways to identify allergic triggers will be essential for optimal EoE management. When utilizing allergen antigen based testing, it is imperative to consider the safety of the testing as well as its accuracy. Novel applications of tools such as component resolved diagnostics hold promise for finding EoE triggering foods/pollens and further tests for reactive lymphocytes that are pathogenic in situ may yield novel therapeutic targets. While much has been understood over the past 20 years, much work remains for researchers working on allergens and their role in EoE.

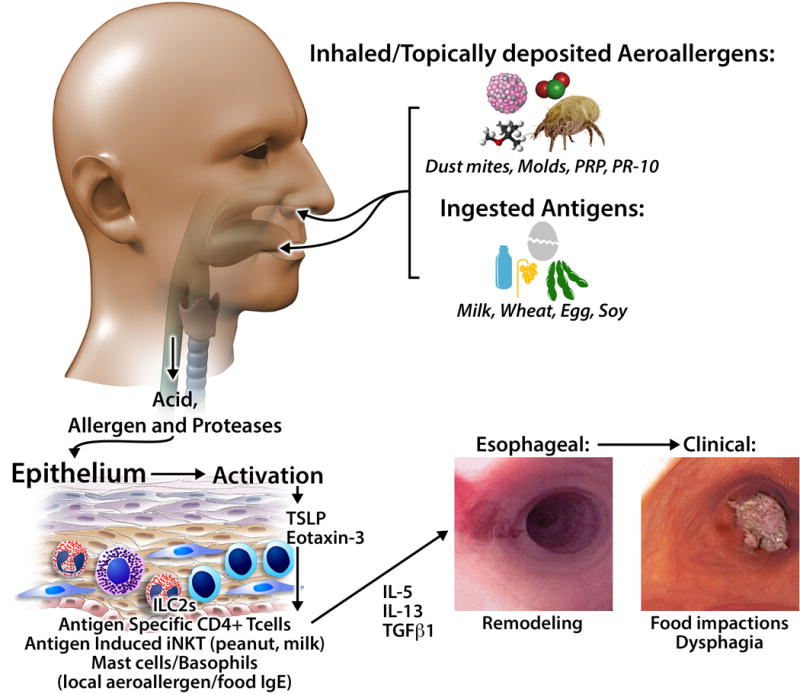

Figure 1. Food and Aeroallergen Antigens in EoE.

Ingested and inhaled antigens, in conjunction with acid and proteases, activate the epithelium to produce chemotactic and activating factors for innate (mast cells, basophils, iNKT, innate lymphoid cells) and adaptive (T cells) immune cells. Infiltrating cells can produce Th2 cytokines such as IL-13 and IL-4 as well as pro-fibrotic factors. Chronic inflammation initiates tissue remodeling with resultant dysphagia, food impactions, and strictures.

What Do We Know?

EoE is an antigen driven disease

The most common EoE triggers are foods, especially milk, egg, soy, and wheat

Antigen-specific IgE seems expendable for disease instigation but may play a role in prognosis or severity

A Th2 cytokine profile predominates EoE disease pathogenesis

Combined skin prick and patch testing may be of utility in children with EoE but does not routinely demonstrate triggering food antigens in adults

Oral immunotherapy to foods and pollens can trigger EoE

What Is Still Unknown?

What is the best approach to test for triggering antigens in EoE?

Are there antigen specific T cells in the esophagus that could be therapeutic targets in EoE?

Are there allergen immunotherapy regimens that could treat EoE?

What are the mechanisms of atopic disease interplay in EoE?

Does pollen or food sensitization have prognostic or severity implications for EoE natural history?

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: JMS has funding from Stuart Starr Endowed Chair and The Children’s Hospital of Food Allergy Fund. NIH/NIAID AI 092135 (S.S.A.), K24AI135034 (S.S.A). Both JMS and SSA have funding from Consortium for Gastrointestinal Eosinophilic Researchers (CEGIR). CEGIR (U54 AI117804) is part of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), NCATS, and is funded through collaboration between NIAID, NIDDK, and NCATS.

Abbreviations

- CRD

component resolved diagnostics

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- TCS

topical corticosteroid

- TGFβ1

transforming growth factor beta-1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: J.M.S. and S.S.A. has no relevant conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Landres RT, Kuster GG, Strum WB. Eosinophilic esophagitis in a patient with vigorous achalasia. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:1298–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Picus D, Frank PH. Eosinophilic esophagitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;136:1001–3. doi: 10.2214/ajr.136.5.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dellon ES. Epidemiology of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:201–18. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly KJ, Lazenby AJ, Rowe PC, Yardley JH, Perman JA, Sampson HA. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1503–12. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90637-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kagalwalla AF, Wechsler JB, Amsden K, Schwartz S, Makhija M, Olive A, et al. Efficacy of a 4-Food Elimination Diet for Children With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1698–707 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molina-Infante J, Arias A, Alcedo J, Garcia-Romero R, Casabona-Frances S, Prieto-Garcia A, et al. Step-up empiric elimination diet for pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis: The 2-4-6 study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez-Garcia S, Rodriguez Del Rio P, Escudero C, Martinez-Gomez MJ, Ibanez MD. Possible eosinophilic esophagitis induced by milk oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1155–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ridolo E, De Angelis GL, Dall’aglio P. Eosinophilic esophagitis after specific oral tolerance induction for egg protein. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106:73–4. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ram G, Lee J, Ott M, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Cianferoni A, Shuker M, et al. Seasonal exacerbation of esophageal eosinophilia in children with eosinophilic esophagitis and allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:224–8 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pesek RD, Rettiganti M, O’Brien E, Beckwith S, Daniel C, Luo C, et al. Effects of allergen sensitization on response to therapy in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, Mishra A, Fulkerson PC, Abonia JP, et al. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:536–47. doi: 10.1172/JCI26679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noti M, Wojno ED, Kim BS, Siracusa MC, Giacomin PR, Nair MG, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-elicited basophil responses promote eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1005–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothenberg ME, Spergel JM, Sherrill JD, Annaiah K, Martin LJ, Cianferoni A, et al. Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:289–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doherty TA, Baum R, Newbury RO, Yang T, Dohil R, Aquino M, et al. Group 2 innate lymphocytes (ILC2) are enriched in active eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:792–4 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merves J, Muir A, Modayur Chandramouleeswaran P, Cianferoni A, Wang ML, Spergel JM. Eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirano I, Aceves SS. Clinical implications and pathogenesis of esophageal remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:297–316. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajan J, Newbury RO, Anilkumar A, Dohil R, Broide DH, Aceves SS. Long-term assessment of esophageal remodeling in patients with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis treated with topical corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:147–56 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Chen D, Mueller J, Dohil R, Hoffman H, et al. Resolution of remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis correlates with epithelial response to topical corticosteroids. Allergy. 2010;65:109–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lieberman JA, Morotti RA, Konstantinou GN, Yershov O, Chehade M. Dietary therapy can reverse esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a historical cohort. Allergy. 2012;67:1299–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuchen T, Straumann A, Safroneeva E, Romero Y, Bussmann C, Vavricka S, et al. Swallowed topical corticosteroids reduce the risk for long-lasting bolus impactions in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2014 doi: 10.1111/all.12455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterson KA, Byrne KR, Vinson LA, Ying J, Boynton KK, Fang JC, et al. Elemental diet induces histologic response in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:759–66. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markowitz JE, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Liacouras CA. Elemental diet is an effective treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adolescents. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:777–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Cianferoni A, Shuker M, Wang ML, Verma R, et al. Identification of causative foods in children with eosinophilic esophagitis treated with an elimination diet. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:461–7 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spergel JM, Beausoleil JL, Mascarenhas M, Liacouras CA. The use of skin prick tests and patch tests to identify causative foods in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:363–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kagalwalla AF, Shah A, Li BU, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, Manuel-Rubio M, et al. Identification of specific foods responsible for inflammation in children with eosinophilic esophagitis successfully treated with empiric elimination diet. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:145–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821cf503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonsalves N, Yang GY, Doerfler B, Ritz S, Ditto AM, Hirano I. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1451–9 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marietta EV, Geno DM, Smyrk TC, Becker A, Alexander JA, Camilleri M, et al. Presence of intraepithelial food antigen in patients with active eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:427–33. doi: 10.1111/apt.13877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenhawt M, Aceves SS, Spergel JM, Rothenberg ME. The management of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:332–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.05.009. quiz 41–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonsalves N, Doerfler B, Yang AH. A prospective clinical trial of six food elimination diet or elemental diet in the treatment of adults with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:S1861. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, Hess T, Nelson SP, Emerick KM, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1097–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henderson CJ, Abonia JP, King EC, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Franciosi JP, et al. Comparative dietary therapy effectiveness in remission of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1570–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf WA, Jerath MR, Sperry SL, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Dietary Elimination Therapy Is an Effective Option for Adults With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molina-Infante J, Arias A, Barrio J, Rodriguez-Sanchez J, Sanchez-Cazalilla M, Lucendo AJ. Four-food group elimination diet for adult eosinophilic esophagitis: A prospective multicenter study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1093–9 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lucendo AJ, Arias A, Gonzalez-Cervera J, Yague-Compadre JL, Guagnozzi D, Angueira T, et al. Empiric 6-food elimination diet induced and maintained prolonged remission in patients with adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study on the food cause of the disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyce JA, Assa’a A, Burks AW, Jones SM, Sampson HA, Wood RA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: summary of the NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel Report. Nutrition. 2011;27:253–67. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill DA, Dudley JW, Spergel JM. The Prevalence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Pediatric Patients with IgE-Mediated Food Allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:369–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maggadottir SM, Hill DA, Ruymann K, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Cianferoni A, Shuker M, et al. Resolution of acute IgE-mediated allergy with development of eosinophilic esophagitis triggered by the same food. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1487–9 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, Franciosi J, Shuker M, Verma R, et al. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:30–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181788282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spergel JM, Andrews T, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, Liacouras CA. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with specific food elimination diet directed by a combination of skin prick and patch tests. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;95:336–43. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erwin EA, Rhoda DA, Redmond M, Ly JB, Russo JM, Hill ID, et al. Using Serum IgE Antibodies to Predict Esophageal Eosinophilia in Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65:520–5. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aalberse RC, Platts-Mills TA, Rispens T. The Developmental History of IgE and IgG4 Antibodies in Relation to Atopy, Eosinophilic Esophagitis, and the Modified TH2 Response. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16:45. doi: 10.1007/s11882-016-0621-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erwin EA, Tripathi A, Ogbogu PU, Commins SP, Slack MA, Cho CB, et al. IgE Antibody Detection and Component Analysis in Patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3:896–904 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erwin EA, James HR, Gutekunst HM, Russo JM, Kelleher KJ, Platts-Mills TA. Serum IgE measurement and detection of food allergy in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez-Sanchez J, Gomez Torrijos E, Lopez Viedma B, de la Santa Belda E, Martin Davila F, Garcia Rodriguez C, et al. Efficacy of IgE-targeted vs empiric six-food elimination diets for adult eosinophilic oesophagitis. Allergy. 2014;69:936–42. doi: 10.1111/all.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warners MJ, Terreehorst I, van den Wijngaard RM, Akkerdaas J, van Esch B, van Ree R, et al. Abnormal Responses to Local Esophageal Food Allergen Injections in Adult Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:57–60 e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Rhijn BD, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Versteeg SA, Akkerdaas JH, van Ree R, Terreehorst I, et al. Evaluation of allergen-microarray-guided dietary intervention as treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1095–7 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Rhijn BD, van Ree R, Versteeg SA, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Sprikkelman AB, Terreehorst I, et al. Birch pollen sensitization with cross-reactivity to food allergens predominates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2013;68:1475–81. doi: 10.1111/all.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erwin EA, Kruszewski PG, Russo JM, Schuyler AJ, Platts-Mills TA. IgE antibodies and response to cow’s milk elimination diet in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:625–8 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Philpott H, Nandurkar S, Royce SG, Thien F, Gibson PR. Allergy tests do not predict food triggers in adult patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis. A comprehensive prospective study using five modalities Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:223–33. doi: 10.1111/apt.13676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kliewer KL, Venter C, Cassin AM, Abonia JP, Aceves SS, Bonis PA, et al. Should wheat, barley, rye, and/or gluten be avoided in a 6-food elimination diet? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1011–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kagalwalla AF, Amsden K, Shah A, Ritz S, Manuel-Rubio M, Dunne K, et al. Cow’s milk elimination: a novel dietary approach to treat eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:711–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318268da40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kruszewski PG, Russo JM, Franciosi JP, Varni JW, Platts-Mills TA, Erwin EA. Prospective, comparative effectiveness trial of cow’s milk elimination and swallowed fluticasone for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:377–84. doi: 10.1111/dote.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clayton F, Fang JC, Gleich GJ, Lucendo AJ, Olalla JM, Vinson LA, et al. Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults is Associated with IgG4 and Not Mediated by IgE. Gastroenterology. 2014 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson JM, Schuyler AJ, Tripathi A, Erwin EA, Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA. IgG4 Component Allergens Are Preferentially Increased in Eosinophilic Esophagitis As Compared to Patients with Milk Anaphylaxis or Galactose-Alpha-1,3-Galactose Allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:AB199. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wright BL, Kulis M, Guo R, Orgel KA, Wolf WA, Burks AW, et al. Food-specific IgG4 is associated with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1190–2 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simon D, Cianferoni A, Spergel JM, Aceves S, Holbreich M, Venter C, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis is characterized by a non-IgE-mediated food hypersensitivity. Allergy. 2016;71:611–20. doi: 10.1111/all.12846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blanchard C, Mingler MK, Vicario M, Abonia JP, Wu YY, Lu TX, et al. IL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sleiman PM, Wang ML, Cianferoni A, Aceves S, Gonsalves N, Nadeau K, et al. GWAS identifies four novel eosinophilic esophagitis loci. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5593. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stone KD, Prussin C. Immunomodulatory therapy of eosinophil-associated gastrointestinal diseases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1858–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wen T, Stucke EM, Grotjan TM, Kemme KA, Abonia JP, Putnam PE, et al. Molecular diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis by gene expression profiling. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1289–99. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sherrill JD, Kiran KC, Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Kemme KA, Collins MH, et al. Analysis and expansion of the eosinophilic esophagitis transcriptome by RNA sequencing. Genes Immun. 2014;15:361–9. doi: 10.1038/gene.2014.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Rodriguez-Jimenez B, Burwinkel K, Collins MH, Ahrens A, et al. A striking local esophageal cytokine expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:208–17. 17 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zuo L, Fulkerson PC, Finkelman FD, Mingler M, Fischetti CA, Blanchard C, et al. IL-13 induces esophageal remodeling and gene expression by an eosinophil-independent, IL-13R alpha 2-inhibited pathway. J Immunol. 2010;185:660–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cianferoni A, Ruffner MA, Guzek R, Guan S, Brown-Whitehorn T, Muir A, et al. Elevated expression of activated TH2 cells and milk-specific TH2 cells in milk-induced eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Isolauri E, Turjanmaa K. Combined skin prick and patch testing enhances identification of food allergy in infants with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;97:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)70277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn T, Beausoleil JL, Shuker M, Liacouras CA. Predictive values for skin prick test and atopy patch test for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:509–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niranjan R, Rayapudi M, Mishra A, Dutt P, Dynda S, Mishra A. Pathogenesis of allergen-induced eosinophilic esophagitis is independent of interleukin (IL)-13. Immunol Cell Biol. 2013;91:408–15. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Akei HS, Mishra A, Blanchard C, Rothenberg ME. Epicutaneous antigen exposure primes for experimental eosinophilic esophagitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:985–94. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rajavelu P, Rayapudi M, Moffitt M, Mishra A, Mishra A. Significance of para-esophageal lymph nodes in food or aeroallergen-induced iNKT cell-mediated experimental eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G645–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00223.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fogg MI, Ruchelli E, Spergel JM. Pollen and eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:796–7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01715-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wolf WA, Jerath MR, Dellon ES. De-novo onset of eosinophilic esophagitis after large volume allergen exposures. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2013;22:205–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moawad FJ, Veerappan GR, Lake JM, Maydonovitch CL, Haymore BR, Kosisky SE, et al. Correlation between eosinophilic oesophagitis and aeroallergens. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:509–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Almansa C, Krishna M, Buchner AM, Ghabril MS, Talley N, DeVault KR, et al. Seasonal distribution in newly diagnosed cases of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:828–33. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Prasad GA, Alexander JA, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Smyrk TC, Elias RM, et al. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis over three decades in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1055–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jensen ET, Shah ND, Hoffman K, Sonnenberg A, Genta RM, Dellon ES. Seasonal variation in detection of oesophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:461–9. doi: 10.1111/apt.13273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang FY, Gupta SK, Fitzgerald JF. Is there a seasonal variation in the incidence or intensity of allergic eosinophilic esophagitis in newly diagnosed children? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:451–3. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000248019.16139.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Philpott HL, Nandurkar S, Thien F, Bloom S, Lin E, Goldberg R, et al. Seasonal recurrence of food bolus obstruction in eosinophilic esophagitis. Intern Med J. 2015;45:939–43. doi: 10.1111/imj.12790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miehlke S, Alpan O, Schroder S, Straumann A. Induction of eosinophilic esophagitis by sublingual pollen immunotherapy. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2013;7:363–8. doi: 10.1159/000355161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patel C, Menon PK. A Complication of Eosinophilic Esophagitis from Sublingual Immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:AB62. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Upadhyaya B, Yin Y, Hill BJ, Douek DC, Prussin C. Hierarchical IL-5 expression defines a subpopulation of highly differentiated human Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:3111–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mahdavinia M, Bishehsari F, Hayat W, Elhassan A, Tobin MC, Ditto AM. Association of eosinophilic esophagitis and food pollen allergy syndrome. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118:116–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Simon D, Straumann A, Dahinden C, Simon HU. Frequent sensitization to Candida albicans and profilins in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2013;68:945–8. doi: 10.1111/all.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Armentia A, Martin-Armentia S, Martin-Armentia B, Santos-Fernandez J, Alvarez R, Madrigal B, et al. Is eosinophilic esophagitis an equivalent of pollen allergic asthma? Analysis of biopsies and therapy guided by component resolved diagnosis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rawson R, Anilkumar A, Newbury RO, Bafna V, Aquino M, Palmquist J, et al. The TGFbeta1 Promoter SNP C-509T and Food Sensitization Promote Esophageal Remodeling in Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fahey LM, Chandramouleeswaran PM, Guan S, Benitez AJ, Furuta GT, Aceves SS, et al. Food allergen triggers are increased in children with the TSLP risk allele and eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2018;9:139. doi: 10.1038/s41424-018-0003-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Abonia JP, Wen T, Stucke EM, Grotjan T, Griffith MS, Kemme KA, et al. High prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with inherited connective tissue disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:378–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Guerrerio AL, Oswald G, Chichester K, Myers L, Halushka MK, et al. TGFbeta receptor mutations impose a strong predisposition for human allergic disease. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:195ra94. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Simon D, Page B, Vogel M, Bussmann C, Blanchard C, Straumann A, et al. Evidence of an abnormal epithelial barrier in active, untreated and corticosteroid-treated eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2017 doi: 10.1111/all.13244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Molina-Infante J, Rodriguez-Sanchez J, Martinek J, van Rhijn BD, Krajciova J, Rivas MD, et al. Long-Term Loss of Response in Proton Pump Inhibitor-Responsive Esophageal Eosinophilia Is Uncommon and Influenced by CYP2C19 Genotype and Rhinoconjunctivitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1567–75. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ramirez RM, Jacobs RL. Eosinophilic esophagitis treated with immunotherapy to dust mites. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:503–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jyonouchi S, Abraham V, Orange JS, Spergel JM, Gober L, Dudek E, et al. Invariant natural killer T cells from children with versus without food allergy exhibit differential responsiveness to milk-derived sphingomyelin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:102–9 e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Greuter T, Bussmann C, Safroneeva E, Schoepfer AM, Biedermann L, Vavricka SR, et al. Long-Term Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis With Swallowed Topical Corticosteroids: Development and Evaluation of a Therapeutic Concept. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1527–35. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ruffner MA, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Verma R, Cianferoni A, Gober L, Shuker M, et al. Clinical tolerance in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rothenberg ME, Wen T, Greenberg A, Alpan O, Enav B, Hirano I, et al. Intravenous anti-IL-13 mAb QAX576 for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]