Abstract

Deaf individuals experience significant obstacles to participating in behavioral health research when careful consideration is not given to accessibility during the design of study methodology. To inform such considerations, we conducted an exploratory secondary analysis of a mixed-methods study that originally explored 16 Deaf trauma survivors’ help-seeking experiences. Our objective was to identify key findings and qualitative themes from consumers’ own words that could be applied to the design of behavioral clinical trials methodology. In many ways, the themes that emerged were not wholly dissimilar from the general preferences of members of other sociolinguistic minority groups—a need for communication access, empathy, respect, strict confidentiality procedures, trust, and transparency of the research process. Yet, how these themes are applied to the inclusion of Deaf research participants is distinct from any other sociolinguistic minority population, given Deaf people's unique sensory and linguistic characteristics. We summarize our findings in a preliminary “Checklist for Designing Deaf Behavioral Clinical Trials” to operationalize the steps researchers can take to apply Deaf-friendly approaches in their empirical work.

The Deaf community is one of the most underserved and understudied populations in behavioral health care, even though the frequency of behavioral health disorders is believed to be higher in the Deaf community than the general population (Fellinger, Holzinger, & Pollard, 2012; Kvam, Loeb, & Tambs, 2007). An American Sign Language (ASL) public health survey confirmed hypotheses about these disparities, with Deaf individuals more likely to have attempted suicide in the past year, to have experienced physical abuse, and to have experienced forced sex than their hearing peers (Barnett, Klein, et al., 2011). Recent research suggests that Deaf people experience twice the rate of trauma as compared to the general hearing population (Anderson & Leigh, 2011; Anderson, Leigh, & Samar, 2011; Berman, Streja, & Guthmann, 2010; Black & Glickman, 2006; Porter & Williams, 2011; Rendon, 1992; Schild & Dalenberg, 2012; Titus, Schiller, & Guthmann, 2008). The presence of such trauma complicates behavioral health treatment, affects multiple domains of functioning (Najavits et al., 2008), and is perhaps one of the underpinnings of the greater functional impairment that Deaf people show compared to their hearing peers—that is, impairments in socialization (Fellinger, Holzinger, Schoberberger, & Lenz, 2005), employment (Fellinger et al., 2005), and physical health (Barnett, Klein, et al., 2011).

One factor contributing to these behavioral health disparities is the lack of access to efficacious treatment. Hearing individuals seeking trauma treatment have many options—private practitioners and behavioral health agencies with access to dozens of evidence-based treatments that show efficacy in the hearing population (Najavits & Anderson, 2015). Conversely, there are no evidence-based behavioral health treatments that have been validated in the Deaf population (Glickman & Pollard, 2013; NASMHPD, 2012). Indeed, the National Association for State Mental Health Program Directors set 34 Deaf behavioral health research priorities in 2012, which emphasize the lack of intervention research in the Deaf population as compared to general and other minority populations—priorities calling for the empirical development and evaluation of trauma treatment approaches, and the examination of research methodologies to adapt evidence-based practices for Deaf people (NASMHPD, 2012). Behavioral health intervention research with the Deaf population is almost non-existent, yet urgently needed.

Deaf-Accessibility of Behavioral Health Treatment

Deaf people's behavioral health disparities are paralleled by disparities in their ability to access treatment. Similar to individuals from other sociolinguistic minority groups, Deaf individuals experience a number of obstacles to seeking help including, but not limited to language barriers in the behavioral health system, limited health literacy, small community dynamics, and stigma (Barnett, Klein, et al., 2011; Barnett, McKee, Smith, & Pearson, 2011; Glickman & Pollard, 2013; McKee & Paasche-Orlow, 2012; McKee et al., 2015; Pollard & Barnett, 2009; Sebald, 2008).

Especially salient for Deaf ASL users attempting to access the healthcare system are issues related to language access. For example, there is a severe lack of ASL-fluent clinicians and ASL interpreters trained in behavioral health or trauma-informed care—a concern frequently discussed in the Deaf behavioral health literature, but with no definitive statistics to quantify the precise level of need (McKee, Barnett, Block, & Pearson, 2011). Additionally, most Deaf individuals experience obstacles to understanding written health materials due to differences in language and development compared to hearing individuals (Glickman, 2013b). Research suggests a fourth-grade median English reading level among Deaf high school graduates (Gallaudet Research Institute, 2003), significantly below the average seventh-to-eighth grade reading level among hearing high school graduates (Institute of Medicine, 2004). Yet, there are few health materials developed in ASL or translated into ASL from written or spoken English (McKee, Barnett, Block, & Pearson, 2011; Pollard, Dean, O'Hearn, & Haynes, 2009), which creates a major barrier to processing and understanding written information about important behavioral health topics.

In addition to these general English literacy concerns, nearly 50% of Deaf individuals may also have inadequate health literacy—6.9 times more likely than hearing individuals (McKee & Paasche-Orlow, 2012; McKee et al., 2015). Indeed, health-related vocabulary among Deaf sign language users parallels non–English-speaking US immigrants (McEwen & Anton-Culver, 1988), and “many adults deaf since birth or early childhood do not know their own family medical history, having never overheard their hearing parents discussing this with their doctor” (Barnett, McKee, et al., 2011). Low health literacy is due to limited language access during key developmental periods and “a lifetime of limited access to information that is often considered common knowledge among hearing persons” (Barnett, McKee, et al., 2011). Examples include limited communication with hearing family members, reductions in incidental learning from auditory information in the natural environment (e.g., information typically overheard in PSAs, news programs, television shows, public conversations), and lack of health education programs available in ASL (McKee & Paasche-Orlow, 2012; McKee et al., 2015; Pollard & Barnett, 2009; Pollard et al., 2009).

When Deaf individuals are able to access behavioral health services, they often express confidentiality concerns similar to other persons living in small communities. These concerns include the high probability that ASL interpreters and Deaf-specialized clinicians belong to the same social circles as the client, as well as the possibility that the client's private information will travel through the “Deaf grapevine” to community members that may judge or even harm them (Barber, Wills, & Smith, 2010).

In addition to these access barriers, members of the Deaf community have also been subjected to a history of mistreatment in the Deaf behavioral health world. For example, early literature on the “psychology of deafness” described Deaf people as emotionally and cognitively deficient compared to hearing people (Myklebust, 1964; Pintner, Eisenson, & Stanton, 1941; Pollard, 1992a)—“language impaired, immature, impulsive, concrete, aggressive, [and] less intelligent” (Glickman, 2013a, p. 12). Many of these assumptions were drawn from research that employed inappropriate psychological measures (i.e., written English measures of intelligence and personality), as there was, and continues to be, a lack of cognitive and emotional assessment measures that have been developed for or standardized with the Deaf population (Glickman, 2013a; Pollard, 1992a, 2002; Vernon, 1995). Moreover, as recently as the 1970s, it was discovered that the majority of mental health practitioners working with Deaf people were practicing without special training or knowledge of Deaf culture and ASL (Levine, 1977). Yet, many of these practitioners staunchly believed that, because of the unfounded deficiencies noted above, Deaf people were “not appropriate or feasible candidates for in-depth, insight-developing, affectively oriented, psychoanalytically oriented, and cognitively oriented psychotherapies. It was believed that only the highly educated, the highly verbal, post-lingually deafened individuals could benefit from such forms of therapy” (Sussman & Brauer, 1999, p. 3).

Deaf individuals’ repeated encounters with these barriers and mistreatment fuel negative perceptions and avoidance of the behavioral healthcare system (Steinberg, Sullivan, & Loew, 1998). Exposure to these microaggressions and subsequent avoidance of the system leads to a number of negative outcomes including misdiagnoses, inappropriate and/or inadequate treatment, magnification of behavioral health related problems, and increased length of treatment with an increased risk of adverse effects (du Feu & Fergusson, 2003; Glickman & Pollard, 2013; Patterson & Baines, 2005; SAMHSA, 2011).

Deaf-Accessibility of Behavioral Health Research

Similar barriers are seen in the field of behavioral health research, including researchers’ use of inaccessible recruitment, sampling, and data collection procedures (Barnett, McKee, et al., 2011; Fellinger et al., 2012; Livermore, Whalen, Prenovitz, Aggarwal, & Bardos, 2011). For example, random-digit-dial surveys fail to sample Deaf ASL users, who use videophones for remote communication rather than standard telephone technology. In-person studies that collect detailed information about behavioral health disorders, including the National Comorbidity Study Replication, sample only English-speaking individuals and make no documentation of provision of interpreters or other accommodations for Deaf individuals (Anderson, Ziedonis, & Najavits, 2014). Studies that rely on written English surveys or other written materials generally adhere to the sixth-to-eighth grade reading levels suggested by most institutional review boards (IRBs), which becomes an issue for the median Deaf high school graduate who reads at a fourth-grade level (Gallaudet Research Institute, 2003). These standard procedures automatically exclude most members of the Deaf community (Livermore et al., 2011) and present a major obstacle to building a foundation of literature on Deaf behavioral health disparities and effective treatments for these disparities.

Access issues in the research world are further exacerbated by ongoing theoretical conflict between members of the Deaf community and the research community about the meaning of “deafness” (McKee, Schlehofer, & Thew, 2013). Researchers generally follow a “medical model,” focusing on how to “cure” or “fix” hearing loss (Bauman, 2004; Ladd, 2003; Lane, 1992). Most Deaf community members, however, follow a “cultural model” and do not believe they are disabled or need to be “fixed,” but that they are members of a minority group with rich culture, shared experience, history, art, and literature (Bauman, 2004; Ladd, 2003; Lane, 1992). This disconnect has fueled a long history of mistreatment against Deaf people in the research world. Common missteps include failure to provide ASL interpreters for participation in research studies, failure to explain research procedures and obtain informed consent in Deaf participants’ primary language, and an overwhelming focus on research questions meant to “solve the problem of deafness” (Lane, 2005; McKee et al., 2013). More egregious abuses include the use of eugenics and sterilization to prevent the expansion of the Deaf community (Lane, 2005; McKee et al., 2013), which underlie a communal feeling of mistrust toward researchers across disciplines (McKee et al., 2013).

Research Objectives

As described above, the barriers experienced by Deaf people in the behavioral healthcare system often carry over into the research world when careful consideration is not given to Deaf individuals’ ability to access various aspects of a study. To better inform such considerations, we conducted an exploratory secondary analysis of a recent mixed-methods study that investigated Deaf trauma survivors’ experiences of help-seeking Anderson, Wolf Craig, & Ziedonis, (in press). Using semi-structured ASL interviews, the original study explored the types of help Deaf trauma survivors received, their barriers and facilitators to recovery, and their recommendations for improving Deaf trauma services within the behavioral healthcare system. The objective of the current exploratory secondary analysis was to identify key findings and qualitative themes from these interviews that could be applied to the design of behavioral clinical trials methodology, with the ultimate goal of improving recruitment, retention, and community engagement with Deaf trauma survivors.

Although we did not specifically interview participants about their experiences with or recommendations for clinical trials methodology, in this secondary analysis we extrapolate from participants’ reported experiences in general behavioral health settings in an attempt to better inform researchers’ design of Deaf-friendly clinical trials. Such “analytic expansion,” in which researchers reuse their own self-collected data to investigate new or extended questions, is frequently used in secondary qualitative research (Thorne, 1998, p. 548), a methodological approach that has received growing recognition and interest since the mid-1990s (Heaton, 2008). To effectively represent the perspectives of our original participants, we adhered to the following recommendations for secondary qualitative research: (1) the secondary analysis was conducted by the Principal Investigator of the original research, who was thoroughly familiar with the original data sets and reports of associated findings, and (2) we collaborated with “appropriate representatives of the issue under study” (i.e., Deaf researchers and clinicians) throughout each stage of the research process (Thorne, 1998, p. 554).

Methods

All study procedures were approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School IRB. Study procedures were designed by the Principal Investigator in collaboration with the Deaf & Allied Clinicians Consult Group, a clinical and research consultation group comprising professionals from the University of Massachusetts Medical School and the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. At the time of study design, this multidisciplinary group included two Deaf and three hearing members with backgrounds in psychology, psychiatry, mental health counseling, mental health case management, or social work.

Study Population

Between March and September 2014, we recruited from across Massachusetts 17 Deaf individuals who had previously experienced trauma. Participants were recruited via online advertisements posted on Craigslist and Deaf-related listservs, and through agencies, clinicians, and case managers who serve Deaf clients. To increase accessibility, these advertisements were disseminated in two forms: ASL digital video and written English flyers.

Recruitment materials directed interested individuals to contact the Principal Investigator (a hearing ASL-fluent psychologist) via email or videophone, the standard telecommunication device for the Deaf. After this initial contact, an appointment was scheduled for screening via videophone, during which the Principal Investigator briefly explained the purpose of the study and the procedures involved, and screened potential participants for the following predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria consisted of (1) age 21 years and older; (2) Massachusetts residency; (3) self-identified hearing status of Deaf or hard-of-hearing; (4) self-identified primary communication mode of ASL; and (5) history of trauma exposure. Trauma exposure was defined as “direct exposure to, witnessing of, learning about, or repeated indirect exposure to aversive details of… death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence,” as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Those excluded from participation were (1) adults legally unable to provide informed consent (i.e., adults with a guardian of person) and (2) prisoners.

Interview Instrument

Eligible participants were scheduled for an in-person study session during which the Principal Investigator obtained informed consent and conducted a 45-minute semi-structured interview in ASL. To make informed consent procedures accessible to participants with diverse linguistic abilities and preferences, the Principal Investigator provided each participant with a copy of the IRB-approved, written English informed consent form and presented each section of the form in ASL (e.g., “What are the risks of being in this study?”, “What happens to information about me?”), pausing after each section to allow for questions and discussion of the information presented.

The semi-structured ASL interview collected basic sociodemographic information, and was also composed of questions from the Life Events Checklist, the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Symptom Scale Interview, and original questions about Deaf individuals’ help-seeking behaviors. Individual interviews were selected over a focus group approach due to the sensitivity of the interview topic as well as concerns about anonymity and confidentiality that are often observed among members of Deaf community (Barber et al., 2010).

Life Events Checklist

The Life Events Checklist queries each participant's level of exposure (i.e., happened to me, witnessed it, learned about it, not sure, doesn't apply) to 16 events that commonly result in posttraumatic stress disorder (e.g., natural disaster, physical assault, sexual assault; Blake et al., 1995). It also includes a final item about exposure to any “other very stressful event or experience” not represented in the previous 16 items. We collected data primarily on events that participants had directly experienced (i.e., happened to me). The Life Events Checklist has demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties as a stand-alone trauma assessment tool with hearing individuals, including adequate temporal stability and good convergence validity with other measures of trauma history (for detailed psychometric properties, see Gray, Litz, Hsu, & Lombardo, 2004).

PTSD Symptom Scale Interview

The PTSD Symptom Scale Interview assesses the presence and severity of current PTSD symptoms (Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993). At the time of data collection, a validated measure of DSM-5 PTSD symptoms was not yet available. Therefore, the 17 semi-structured interview items represented the diagnostic criteria of PTSD as outlined in the DSM, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Respondents were asked to report their symptoms during the past 2 weeks. For each item, the interviewer rated the frequency and severity of the symptom (from 0 = not at all to 3 = five or more times per week/very much). The PTSD Symptom Scale Interview has shown evidence of high internal consistency, high inter-rater reliability, and is strongly correlated with both the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (Foa & Tolin, 2000).

Help-Seeking Behaviors

Interview questions regarding help-seeking were developed by the Principal Investigator and the Deaf & Allied Clinicians Consult Group. We created this series of three nested questions to explore participants’ receipt of informal and formal support after trauma:

- After your experience(s) of trauma, did you get help from friends/family/peers?

- If yes: Who? What did you find most helpful? What was not helpful? What could they have done to better support you?

- If no: What prevented you from getting help from friends/family/peers? What could change to increase your likelihood of seeking their help in the future?

- After your experience(s) of trauma, did you get help from a professional?

- If yes: Who? What sort of treatment did they provide? What did you find most helpful? What was not helpful? What could they have done to better support you?

- If no: What prevented you from getting help from a professional? What could change to increase your likelihood of seeking their help in the future?

- How likely are you to seek professional trauma treatment at the current time?

- 0 = extremely unlikely to 4 = extremely likely.

Translation Process

Interview questions were adapted from written English into ASL in collaboration with the Deaf & Allied Clinicians Consult Group. Item adaptation focused on preserving linguistic equivalency and psychological conceptual equivalency between the English and ASL interview questions. A typical three-stage procedure was used (i.e., translation, back-translation, equivalence comparison), similar to the translation of other psychological measures into ASL (Brauer, 1993).

Data Analysis

Interview responses were entered into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database. We had incomplete data for 1 participant, bringing our final sample size to 16 participants.

Quantitative Analyses

Quantitative data were exported to SPSS Statistics Version 22. For this secondary analysis, descriptive statistics were used to summarize the rates of screening and recruitment, number and types of trauma events experienced, rates of full and partial PTSD, rates of formal help-seeking in the past, likelihood of seeking trauma treatment in the future, and length of administration time for each interview.

Rates of full PTSD were calculated according to instructions in the PTSD Symptom Scale Interview manual (Hembree, Foa, & Feeny, 2002). A diagnosis of full PTSD was determined by counting the number of PTSD symptoms reported per symptom cluster (i.e., a frequency/severity rating of 1 or greater); one re-experiencing symptom, three avoidance symptoms, and two arousal symptoms were needed to meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Also required were duration of symptoms greater than 1 month and the presence of clinically significant distress or impairment (Hembree et al., 2002).

Rates of partial PTSD were calculated using the most common strategy in the PTSD literature, as outlined in A Guide to the Literature on Partial PTSD (Schnurr, 2014). A diagnosis of partial PTSD was assigned when the participant met criteria for at least one re-experiencing symptom, one avoidance symptom, and one arousal symptom (Schnurr, 2014). Requirements for 1-month duration and clinically significant impairment remained.

Qualitative Analyses

Qualitative data were exported to ATLAS.ti, where interview responses were analyzed for recurring themes and perspectives that are applicable to the design of behavioral clinical trial methodology. Again, it should be noted that, in the original study, we did not interview participants about their experiences with or recommendations for clinical trials methodology. Rather, we queried participants about their general experiences seeking behavioral health treatment and did not delineate between treatment provided in regular clinic settings and treatment provided as part of clinical research studies. From these qualitative data, we attempted to identify key themes that could better inform researchers’ design of Deaf-friendly clinical trials, an “analytic expansion” approach that is frequently used in secondary qualitative research (Thorne, 1998, p. 548).

To identify these themes, we conducted a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) which relied on two major techniques: (1) content analysis, where the number of similar responses to questions were tallied and described; and (2) a summary of the answers to the questions outlined by Casey (Krueger, 1998). Such questions included What are the participants saying? What are they feeling? What is really important? What are the themes? Are there any comments said only once but deserve to be noted? Which quotes really give the essence of the conversation? What ideas will be especially useful for designing clinical interventions with this population?

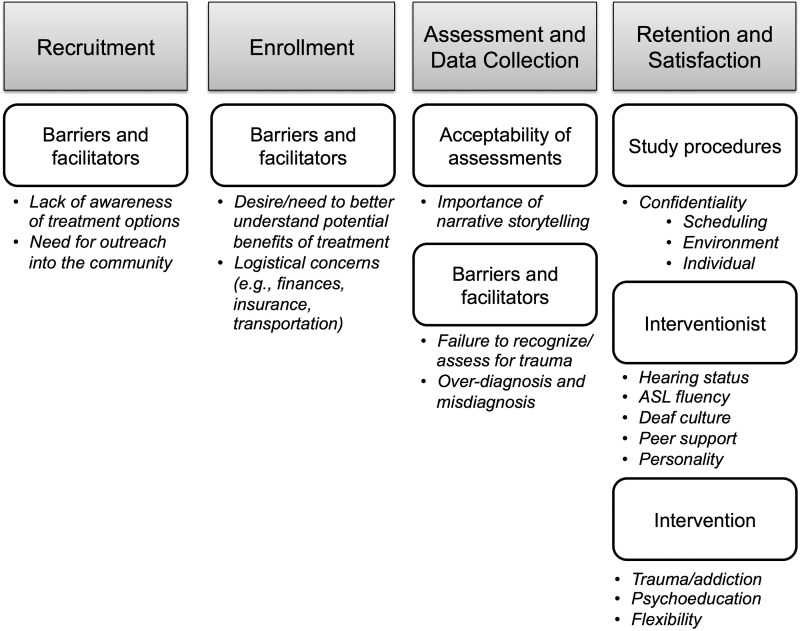

Using these techniques, we defined a nested coding structure based on behavioral clinical trial feasibility outcomes, that is, information that is relevant to recruitment, enrollment, assessment and data collection, and participant retention and satisfaction. To summarize our findings, we ran a code report for each parent code of interest and summarized the prevailing themes. See Figure 1 for a visual representation of our coding structure.

Figure 1.

Qualitative Coding Structure.

Results

We enrolled and obtained complete data from a total of 13 female and 3 male participants between March and September 2014. Most participants identified as being culturally Deaf, white, middle-aged, and heterosexual (Table 1). Most were middle-aged, had attended at least some college, and were employed full-time or collecting Supplemental Security Income/Social Security Disability Insurance at the time of data collection.

Table 1.

Study sample characteristics

| Sociodemographic characteristics | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 21–34 | 23.5 |

| 35–44 | 11.8 | |

| 45+ | 64.7 | |

| Ethnicity | Not Hispanic/Latino | 82.4 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 17.6 | |

| Race (select all that apply) | White | 100.0 |

| Black/African-American | 5.9 | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5.9 | |

| Sexual orientation | Straight | 76.5 |

| Gay/lesbian | 17.6 | |

| Bisexual | 5.9 | |

| Hearing status (self-identified) | Deaf | 88.2 |

| Hard-of-Hearing | 5.9 | |

| Not sure | 5.9 | |

| Preferred language | American Sign Language | 88.2 |

| Spoken English | 5.9 | |

| Other | 5.9 | |

| Use of assistive hearing device | No device | 47.1 |

| Hearing aid | 41.2 | |

| Cochlear implant | 11.8 | |

| Parental hearing status | Both hearing | 82.4 |

| Both Deaf | 17.6 | |

| Parental communication method (select all that apply) | Spoken English | 52.9 |

| American Sign Language | 29.4 | |

| Home sign | 11.8 | |

| Signed Exact English | 5.9 | |

| Other | 41.2 | |

| School type | Deaf school only | 52.9 |

| Both Deaf and mainstream school | 29.4 | |

| Mainstream school only | 17.6 | |

| Education level | Some high school | 17.6 |

| High school diploma | 23.5 | |

| Some college | 23.5 | |

| 4-year college degree or above | 35.3 | |

| Employment status | Collecting SSDI/SSI | 47.1 |

| Employed full-time | 35.3 | |

| Employed part-time | 17.6 | |

Findings are organized below according to behavioral clinical trial feasibility outcomes: recruitment, enrollment, assessment and data collection, and participant retention and satisfaction. Select participant quotes are included to elucidate our findings.

Recruitment

Rates of Participant Screening

Over a period of 30 weeks, a total of 18 interested individuals contacted our research team with hopes of participating in a study about “trauma services for the Deaf community.” If this rate of screening were applied to a 1-year period of recruitment for a trauma treatment clinical trial, this could translate to a total of 30 participants potentially willing to participate. Rates of actual study enrollment (n = 17) are described below.

Qualitative Findings Regarding Barriers and Facilitators to Recruitment

Participants reported that one of the primary barriers to seeking professional help for trauma was their general lack of awareness about treatment options, regardless of whether these treatment options were offered in general clinical settings or in research settings—“I didn't know about treatment because I was Deaf.” They recommended that providers reach out into the community and have a community presence in order to attract Deaf individuals to their clinical practice:

“Go to Deaf events, workshops, because many Deaf people don't know about available services. Deaf people prefer to see you in person, hear about your experience, qualifications, etc. in person.”

“Go to events to meet people—someone there needs treatment or knows someone else who needs treatment. Visit group homes. Make yourself well known, get into the network. We trust what we see for ourselves.”

“If I know the therapist was Deaf or signed…how it is advertised. Should get exposure through health fairs, booths, with the therapist there. If I meet you, I might be more motivated to open up.”

“Should be involved in the community and socialize, but keep professional boundaries—not be so stiff.”

Similar recommendations could be used by clinical trials researchers to improve recruitment rates of Deaf research participants; however, during this recruitment process, researchers need to clearly delineate between the procedures and potential risks/benefits of clinical treatment versus clinical trials research to avoid the possibility of therapeutic misconception, an issue explored in depth in the Discussion section.

Enrollment

Rate of enrollment

Of the 18 interested individuals who contacted the study team, 17 met our predefined inclusion criteria (i.e., Deaf or hard-of-hearing ASL users at least 21 years old, currently living in Massachusetts, with a self-reported history of trauma exposure). All 17 eligible individuals chose to enroll in the study. If this rate of enrollment was applied to a 1-year clinical trial with similar inclusion criteria, this could translate to approximately 29 enrolled participants. One enrolled participant provided incomplete data during the interview and was, therefore, excluded from further quantitative findings.

Rates of full and partial PTSD

For those researchers considering behavioral clinical trials that require a diagnosis of PTSD for study inclusion, eight (50%) of our 16 trauma-exposed participants met full criteria for current PTSD. When these criteria were expanded to include partial PTSD, 11 participants (69%) satisfied the criteria for either full or partial PTSD.

Interest in behavioral health treatment

Approximately two-thirds of the sample (69%) reported that they sought help from a professional following their experiences of trauma. Regarding current interest in treatment, more than half (56%) reported that they were extremely likely or likely to seek professional treatment for trauma at the current time. Approximately one-fifth (19%) of study participants were neither interested nor disinterested in treatment, while one-quarter indicated that they were unlikely or extremely unlikely to seek treatment at the current time. Although these findings referred to participants’ general interest in participating in trauma treatment, it is possible that trauma survivors might show similar levels of interest in participating in a clinical research study in which their trauma treatment is being studied. Indeed, trauma survivors may be more likely to engage in research if they believe that there is a possibility of benefit from the experimental treatment being provided (i.e., potential for reduction in PTSD symptoms), as opposed to participating in research that investigates their experiences of trauma but provides no intervention or possibility of direct benefit to the participant.

Qualitative findings regarding barriers and facilitators to enrollment

Despite the general interest in professional treatment expressed by participants, they also reported that they needed to better understand the potential benefits of treatment to make a decision about whether to enroll in treatment or not—“Realizing how treatment could help. Before, I thought, ‘For-for?’ (i.e., ‘What for?’).” For clinical trials researchers, these findings highlight the importance of informed consent procedures that clearly outline the potential benefits and risks of each treatment arm. However, such comments also suggest the importance of making potential benefits known during outreach and recruitment efforts, as eligible individuals may not contact the research team without first having a good understanding of how the study might help them or help the Deaf community at large.

Participants also reported logistical barriers to enrolling in treatment, including financial concerns, insurance difficulties, and distance to clinicians—“There are not enough services in the whole state, have to go too far for treatment.” Clearly, participant finances and access to transportation are issues that all clinical trials researchers also need to consider; however, these issues may be more salient when recruiting from any small, highly-dispersed community, of which many of its members rely on fixed incomes. For such target populations, every effort should be made to design studies that incur no cost to the participant, especially if the participant's insurance company is not billable for experimental interventions provided as part of a behavioral clinical trial.

Assessment and Data Collection

Qualitative findings regarding the comprehension and acceptability of assessment instruments

During the conduct of 17 interviews, no participants reported difficulty understanding the current ASL translation of the Life Events Checklist or the PTSD Symptom Scale Interview. One participant, however, provided incomplete data due to a general inability or unwillingness to follow the question-and-answer structure of the interview. Rather, this participant preferred to tell the interviewer their detailed personal story from start to finish, emphasizing the importance of such a narrative approach in Deaf culture—“Let them tell their story—don't interrupt.” Where possible, allowing such a narrative approach to the assessment process (as opposed to a highly-structured, standardized interview approach) might improve the level of disclosure among Deaf research participants. For example, the study assessor could alert the participant to the fact that there will be many short answer questions during the assessment process, but also allow time for the participant to tell their narrative in an open-ended way (e.g., “Tell me about yourself first.”).

Qualitative findings regarding the barriers and facilitators to assessment

Regarding their prior experiences with assessment, participants reported disappointment that some providers had failed to assess for trauma and had, therefore, overlooked the impact of trauma experiences on their care—“[The therapist] did not identify the emotional abuse. I almost admitted it, but I was afraid.” While participants expressed a desire for increased assessment and identification of trauma experiences, they also expressed concerns about providers’ focus on pathology, both overdiagnosing and misdiagnosing them:

“With the newer therapist, she never explained diagnosis and wasn't honest; there was no trust; she didn't believe my story; she decided to diagnose me with Borderline; many wrong labels.”

“Diagnoses, labels, medications—lousy!”

Generalizing these findings to the design of behavioral clinical trials, this suggests that researchers must aim to achieve a delicate balance between conducting a sufficient amount of assessment to accurately identify major life events and behavioral health disorders, without flooding participants with assessment instruments that cause them to feel evaluated or judged. Possible approaches include: taking the time to thoroughly explain how assessment benefits both the research and the participant (i.e., to inform treatment development, to track participants’ progress, to monitor for adverse events); allowing for open-ended responses when possible; asking participants, “Is there anything else you would like to comment on? Do you have any other concerns?”; and, exercising care when sharing diagnoses or other health findings that might arise during the research study.

Participant Retention and Satisfaction

Qualitative findings regarding study procedures

Participants overwhelmingly reported that procedures to protect their confidentiality were of utmost importance to their treatment satisfaction and likelihood of remaining in treatment, given the small, close-knit nature of the Deaf community:

“[I want] a professional therapist who knows confidentiality law and is not a rookie. I had a therapist once who violated confidentiality to my mom.”

“It's a small Deaf community. I didn't want people to gossip, I didn't want my ex to find me.”

Given these concerns, participants made a number of suggestions about how best to protect their confidentiality, many of which could directly be applied to researchers conducting behavioral clinical trials with Deaf participants. First, participants recommended that providers “be flexible with hours” and avoid scheduling “back-to-back appointments with other Deaf clients; they pass each other or see each others’ cars (breaks confidentiality).”

Second, participants made recommendations regarding the treatment environment to protect their confidentiality and create a space where they could feel safe:

“The environment should feel safe and be hidden.”

“It should be homey, not cold and institutional.”

Third, many participants expressed a preference for individual treatment—“If Deaf people know each other, they are ashamed to share.” Even with these confidentiality concerns, some others noted a desire for group treatment—“you feel validated, like a breast cancer support group”—however, most participants indicated that they would ultimately not join such a group in order to protect their privacy, suggesting that recruitment and retention for group research interventions might be especially difficult within this particular population.

Qualitative findings regarding study interventionists

Participants made conflicting reports about whether they preferred a Deaf or hearing behavioral healthcare provider. Those who stated a preference for a hearing clinician primarily did so because of confidentiality concerns, as described above—“I'm more comfortable with a hearing provider who knows sign because not see at Deaf events. Deaf may break confidentiality and spread your information.”

Regardless of preferred hearing status, participants all stated a preference for a provider fluent in ASL who is able to provide treatment through direct communication, rather than through an interpreter:

“Sign…Can see the ‘real me,’ not through an interpreter.”

“I didn't want to work with interpreters—no privacy.”

“I prefer direct communication, feels like home.”

Equally as important was the clinician's awareness of Deaf culture, their ability to “know Deaf culture through and through.”

To ensure such in-depth understanding of Deaf culture and fluency in ASL, many participants expressly reported a preference for receiving peer support over professional support:

“If there is an authority in the room, the clients will reject them—peers are better.”

“Youshould ‘get’ Deaf, like peer support. Common bond, empathy. If not, will miss empathy.”

“Have similar experiences so you can empathize—same frustrations, same experiences of oppression.”

“She was open about herself. Shared her own experiences, felt like a peer.”

Those participants who preferred to seek professional support indicated that they were most likely to be satisfied with highly experienced clinicians who delicately balanced bluntness, honest feedback, and confrontation with a sense of calm, compassion, and composure:

“She was soft, sweet like a mother. But it didn't help.”

“Direct, blunt, told the truth. She knew how to confront me in the right way.”

“They have a good heart, make me feel comfortable.”

“Some staff have attitudes or bad facial expressions, not appropriate way; this triggers clients to blow up.”

For behavioral clinical trials researchers, these findings suggest that hiring a diverse group of study clinicians who have a common set of foundational skills may be the best approach to designing a trial. In other words, it may be preferable to employ both hearing and Deaf clinicians who have minimum qualifications of fluency in ASL, knowledge of Deaf culture and Deaf history, and who are compassionate yet direct in their clinical approach. Where possible, incorporating opportunities for peer support may also increase participant satisfaction and retention in behavioral clinical trials.

Qualitative findings regarding study interventions

Participants reported that they would be most interested in engaging in treatments that target trauma, addiction, and provide psychoeducation:

“They should give more resources and education, so that Deaf people do not remain ignorant.”

“Some therapists never talked about domestic violence. I thought the abuse was my fault. I thought that I was not nice, that I was a bitch. I was angry, not innocent. I believed that ‘abuse only happens to innocent people.’”

“Bad programs deny trauma. They have no support for trauma programs. Good programs link trauma with addictive behavior.”

“It's good to discuss about drugs and relapse. I like the support of therapy, talking.”

“We need dual diagnosis therapy for people who have trauma and substance problems.”

Participants expressed a preference for treatment that would be highly flexible. The ideal intervention would allow for frequent follow-ups and check-ins—“keep in touch and check in to see how we're doing (because we keep it to ourselves).” It would also allow for assistance with case management, crisis sessions, and emergency contacts on an as-needed basis, intervention options that are not often available in structured, standardized research protocols. As much as possible, such flexibility should be incorporated into the design of Deaf behavioral clinical trials—for example, tracking the number of crisis sessions delivered or emergency contacts made as a potential mediator of treatment outcome (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002) or offering a limited number of “booster sessions” after study completion (Najavits, 2002). However, as discussed in more detail below, researchers should also take sufficient time to educate potential participants about the theoretical basis behind research protocol standardization and the resulting limits on flexibility that this can create when delivering research interventions.

Discussion

Between March and September 2014, we interviewed 16 Deaf individuals to explore the types of help they received after trauma, the barriers and facilitators to recovery from trauma, and recommendations for improving Deaf trauma services within the behavioral healthcare system ([redacted for anonymity], under review). The objective of the current exploratory secondary analysis was to identify key findings and qualitative themes from these interviews that could be applied to the design of research methodology, with the ultimate goal of improving community engagement, recruitment, and retention with Deaf trauma survivors.

For clinical trials researchers planning to recruit Deaf individuals to trauma intervention studies, our findings suggest an estimated recruitment rate of 30 individuals per year per research site. Deaf individuals are similar to members of other communities whose primary language is not English, in that the absence of bilingual informational material about research studies becomes a significant barrier to research recruitment (George, Duran, & Norris, 2014). Researchers’ recruitment efforts may, therefore, be improved by creating advertisements in ASL and distributing these materials to Deaf-related listservs, Facebook groups, and agencies that serve Deaf individuals. More important to recruitment, however, is the researcher's visual presence within the Deaf community—actually attending Deaf events and presenting at Deaf workshops—thereby allowing members of the community to “hear about your experience, qualifications” and “trust what [they] see for [them]selves.” This emphasis on overcoming mistrust is not unique to recruiting Deaf research participants, but is a common thread that weaves through culturally-sensitive empirical work with any marginalized or oppressed group (George et al., 2014; Leung, Yen, & Minkler, 2004). Although it is important for researchers (especially hearing researchers) to create in-roads and visual presence within the Deaf community, it is perhaps more essential to create in-roads and presence of Deaf people within the research community:

Some of the hesitation to participate in research can be countered by having communities become full partners in the research process, beginning with community identification of an issue. CBPR [Community-Based Participatory Research] methods particularly lend themselves to research projects undertaken in populations that are ‘other’ to the researchers. (Leung et al., 2004, p. 503)

Regarding enrollment rates, nearly all the Deaf trauma survivors recruited to the original study chose to enroll in an interview-based study (the equivalent of approximately 29 enrollments per year). More than half reported that they were currently interested in receiving professional trauma treatment. Reported barriers that could interfere with enrollment in a behavioral clinical trial could include a lack of reliable transportation and limited finances, common concerns among many sociolinguistic minority groups (George et al., 2014). Yet, one of the greatest barriers to enrollment reported by participants was a general lack of understanding of the purpose of treatment. Indeed, a recent systematic review of the barriers and facilitators to minority group members’ research participation found that two of the primary barriers shared across groups were mistrust (as discussed above) and lack of access to information about research opportunities (George et al., 2014). To better engage members of the Deaf community, or any sociolinguistic minority group, researchers need to provide clear, accessible information about the potential benefits and risks of experimental interventions when engaging in outreach and recruitment efforts, as well as informed consent procedures.

Informed consent for enrollment in behavioral health treatment or clinical research studies, although not overtly mentioned by our participants, is a key area of consideration for behavioral clinical trials researchers working with the Deaf population. Most Deaf individuals experience significant obstacles to engaging in informed consent due to the language barriers and health literacy concerns outlined in the introduction of this article (Anderson & Kobek Pezzarossi, 2012; Barnett, McKee, et al., 2011; Glickman, 2013b; McEwen & Anton-Culver, 1988). Yet, most informed consent protocols rely on lengthy English consent forms that include biomedical jargon and legalistic IRB language. Such methods fail to produce a fully informed Deaf research participant and call for adaptations above-and-beyond simple translation of informed consent materials into ASL (Pollard et al., 2009). Therefore, one potential starting place for addressing inaccessible research methods and mistrust of the research community is the careful reconsideration of the traditional informed consent process, and the pursuit of formal empirical investigations into how to design Deaf-accessible informed consent procedures.

When enrolling participants, it is also important for researchers to make clear the distinction between treatment and clinical research—a key concern associated with the ethical issue of therapeutic misconception (Applebaum, Lidz, & Grisso, 2004). Therefore, in addition to describing potential benefits and risks of study interventions during outreach and recruitment efforts, researchers need to be extremely clear that research is not treatment and provide psychoeducation to the community about therapeutic misconception. This information should be carefully reiterated during informed consent procedures to ensure that participants do not believe that they will be provided access to the best treatment possible, which is not the case in a randomized clinical trial (where participants are randomly assigned to one of multiple treatment arms) or in any study with a placebo arm. Additionally, the researcher should make clear early on that the differences in clinical treatment and clinical trials research will inherently cause research interventions to be less flexible than clinical treatment. Taking such care to clarify these issues early on will help to avoid a significant ethical misstep on the part of the research team, as well as allow participants to have more realistic expectations about what clinical trials research entails.

Current themes from our analyses that can be applied to assessment and data collection include conducting assessments in the participant's preferred language; being transparent about the diagnostic process, but avoiding an overemphasis on pathology; and allowing time and space for participants to “tell their story.” Such a person-centered assessment approach has been previously recommended for general behavioral research (Bates, 2004); however, it appears that the role of the narrative among culturally Deaf individuals has deeper ties that may be rooted in the oral tradition of Deaf literature (Ladd, 2003). Therefore, interfering with this narrative approach during the research process would be culturally incongruent on the part of the researcher and could negatively impact the likelihood of participants remaining in a clinical research study, especially a longitudinal study with multiple assessment time points.

To further improve retention rates and satisfaction, participants reported that they preferred working with clinicians who are fluent in ASL and knowledgeable about Deaf culture, being treated in a direct but compassionate manner, and being provided accessible psychoeducation about topics that impact their community. Even more important to retention and satisfaction was the research team's role in protecting participants’ confidentiality, a concern frequently expressed by other research participants from small, highly-connected communities (Damianakis & Woodford, 2012). Our participants strongly recommended that the research team have in-depth knowledge of and commitment to adhere to procedures designed to protect confidentiality. They also recommended that research appointments be spaced appropriately (i.e., 15–30 minutes apart) so that Deaf participants do not cross paths in waiting rooms or parking lots. Although the research environment may be flexible enough to handle such a staggered scheduling procedure, eventually translating this research finding into clinical practice may present a challenge, as funding for a typical treatment environment relies on insurance reimbursement of face-to-face time with therapy clients (and, therefore, causes appointments to be scheduled tightly back-to-back or double-booked to maximize billing revenue). Yet, even when such scheduling precautions are put into place, there is still a chance that Deaf research participants who already know each other from the community may encounter each other at your study site. To prepare for these situations, it is prudent to include a discussion of this particular confidentiality concern during informed consent procedures—a discussion of the participants’ risk of being recognized by other participants as well as the importance of respecting other participants’ privacy and confidentiality, if this should occur. This early discussion will set the foundation for an ongoing, open dialogue about privacy concerns throughout the course of a clinical trial and, likely, result in fewer violations of confidentiality and improved participant satisfaction and retention.

In many ways, the themes that emerged from the current analysis are what we would expect of any research participant that is a member of a sociolinguistic minority group, Deaf or hearing—a need for communication access, empathy, respect, strict confidentiality procedures, trust, and transparency of the research process. However, how these themes are applied to the inclusion of Deaf research participants is distinct from any other sociolinguistic minority population, given Deaf people's unique sensory and linguistic characteristics (i.e., a visual community as opposed to an auditory community). To more clearly operationalize the steps researchers can take to apply Deaf-friendly approaches in their empirical work, at a minimum, we have summarized our findings in a preliminary “Checklist for Designing Deaf Behavioral Clinical Trials” (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Checklist for Designing Deaf Behavioral Clinical Trials.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The current secondary analysis extrapolated from Deaf trauma survivors’ reported experiences in general behavioral health settings in an attempt to better inform researchers’ design of Deaf-friendly clinical trials. Although previous literature has discussed the importance of cross-cultural ethics in the conduct of Deaf-related research (Glickman & Pollard, 2013; McKee et al., 2013; Pollard, 1992b; Singleton, Jones, & Hanumantha, 2012), ours is the first known attempt to draw our empirical recommendations directly from Deaf trauma survivors in their own words (Stein & Mankowski, 2004). Another key strength of our study was the use of Deaf-accessible methods (e.g., recruitment materials, informed consent, and interviews provided in ASL; provision of Certified Deaf Interpreters as needed). This is largely attributable to collaboration with Deaf colleagues throughout each step of the research process, including when designing our methods, selecting and translating trauma assessments, interpreting study findings, and preparing this manuscript.

Our primary study limitation was the small sample size. Additionally, our sample was primarily white, middle-aged, and heterosexual. Inasmuch, the results of this small exploratory study should be generalized further with caution. Our second limitation was the use of measures with unknown psychometric properties in the Deaf population; however, we attempted to relatively reduce the impact of this limitation by administering all measures in ASL rather than written English.

A third limitation was that participants were not directly asked about their experiences with or recommendations for participating in behavioral clinical trials—rather, we drew from participants’ experiences with general behavioral health treatment to make assertions about receiving treatment in clinical research settings. Although such “analytic expansion” is frequently used in secondary qualitative research (Thorne, 1998, p. 548), in making this extrapolation, our exploratory analyses inherently conflated the issues of treatment and clinical research—a key concern associated with the ethical issue of therapeutic misconception (Applebaum et al., 2004). We would like to recognize here that clinical research is not analogous to treatment and that this important distinction, therefore, influences any sort of generalization to the research environment. Although we believe that there was sufficient goodness-of-fit between the primary database and the secondary analysis objectives (Heaton, 2008; Long-Sutehall, Sque, & Addington-Hall, 2010; Thorne, 1998), we may not have identified additional barriers and facilitators specific to the research process that would have emerged with direct questioning about clinical trials; for example, Deaf people's communal feeling of mistrust toward researchers (Barnett, McKee, et al., 2011; McKee et al., 2013) and concrete recommendations for how researchers might address this mistrust.

A fourth limitation revolves around the “checks and balances” process for qualitative analyses. As the current study was a secondary analysis of data collected in 2014, we were unable to re-engage participants to review their interview transcripts for accuracy nor to give them a chance to reflect on whether they had any additional or different thoughts regarding the interview content. Additionally, we did not employ an outside analyst to examine and confirm the qualitative themes identified by the Principal Investigator and the Deaf colleagues involved in interpreting study findings. As such, current results could be influenced by bias that these individuals brought to the qualitative work. Future research on this topic should, therefore, include methodological procedures to re-engage interview participants to review and reflect on their interview transcripts, as well as employ a qualitative analyst relatively external to the research team to confirm the results of the thematic analysis.

Study Implications and Future Directions

Despite these limitations, our results suggest that, as behavioral clinical trials researchers, we need to better listen to Deaf people in order to design methods that are more conducive to their meaningful participation in our research. This secondary analysis is a preliminary attempt to do just that. To confirm and build upon current findings, future research should directly investigate the themes identified from our secondary analysis by querying a large, national sample of Deaf individuals about their experiences in the research world and their recommendations for designing Deaf-accessible clinical research methods. Ideally, this work would occur in collaboration with members of the Deaf community from the very beginning of the study's inception—the essence of CBPR (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). Such early collaboration will ensure that the research questions are relevant and the study design accessible and engaging to members of the Deaf community (Barnett, McKee, et al., 2011; Pollard, 1992b), thereby creating a parallel process in which research being conducted about Deaf-accessible study methods is accessible in and of itself.

Once effective methodologies have been identified, it is imperative that researchers leverage these approaches to develop, adapt, and evaluate behavioral health treatments for Deaf individuals. As additional research emerges about Deaf health disparities—both medical and behavioral—the need for efficacious treatment options becomes clear. Yet, there is no empirical evidence that the treatment approaches that we currently use with Deaf clients are successful. Establishing a toolkit of evidence-based treatments and disseminating these practices throughout the Deaf behavioral healthcare system is one initial step toward reducing Deaf people's health disparities and beginning to approximate the abundance of treatment options available to the general hearing community.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Deaf & Allied Clinicians Consult Group for their guidance on this project: Gloria Farr, LICSW; Susan Jones, LMHC; Lisa Mistler, MD; and Gregory Spera. We would also like to thank Drs. Robert Goldberg, Kate Lapane, Catherine Dube, and Christine Ulbricht for their feedback during the preparation of this manuscript.

Note

The US Deaf community is a sociolinguistic minority group of approximately 500,000 persons who communicate primarily using American Sign Language (Mitchell, Young, Bachleda, & Karchmer, 2006). Members of this community are unique from other individuals with hearing loss in their identification as a cultural—not disability—group and are delineated by use of the capital “D” in “Deaf” (Ladd, 2003; Lane, 1992).

Funding

This work was partially supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR000160. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest were reported.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; (4th Ed.)., text revisionWashington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. L., & Kobek Pezzarossi C. M. (2012). Is it abuse? Deaf female undergraduates’ labeling of partner violence. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 17(2), 273–286. 10.1093/deafed/enr048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. L., & Leigh I. W. (2011). Intimate partner violence against deaf female college students. Violence Against Women, 17(7), 822–834. 10.1177/1077801211412544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. L., Leigh I. W., & Samar V. (2011). Intimate partner violence against deaf women: a review. Aggression and Violent Behavior: A Review Journal, 16(3), 200–206. 10.1016/j.avb.2011.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. L., Wolf Craig K. S., & Ziedonis D. M (in press). Deaf people’s help-seeking following trauma: Experiences with and recommendations for the Massachusetts behavioral healthcare system. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Anderson M. L., Ziedonis D. M., & Najavits L. M. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder comorbidity among individuals with physical disabilities:findings from the national comorbidity survey replication. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(2), 182–191. 10.1002/jts.21894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum P. S., Lidz C. W., & Grisso T. (2004). Therapeutic misconception in clinical research: Frequency and risk factors. IRB: Ethics & Human Research, 26(2), 1–8. 10.2307/3564231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber S., Wills D., & Smith M. J. (2010). Deaf survivors of sexual assault In Leigh W. (Ed.), Psychotherapy with deaf clients from diverse groups (2nd ed., pp. 320–340) Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett S., Klein J. D., Pollard R. Q. Jr., Samar V., Schlehofer D., Starr M., . . . Pearson T. A. (2011). Community participatory research with deaf sign language users to identify health inequities. American Journal of Public Health, 101(12), 2235–2238. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett S., McKee M., Smith S. R., & Pearson T. A. (2011). Deaf sign language users, health inequities, and public health: opportunity for social justice. Preventing Chronic Disease, 8(2), A45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates J. A. (2004). Use of narrative interviewing in everyday information behavior research. Library & Information Science Research, 26(1), 15–28. 10.1016/j.lisr.2003.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman H. D. (2004). Audism: exploring the metaphysics of oppression. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 9(2), 239–246. 10.1093/deafed/enh025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman B. A., Streja L., & Guthmann D. S. (2010). Alcohol and other substance use among deaf and hard of hearing youth. Journal of drug education, 40(2), 99–124. 10.2190/DE.40.2.a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black P. A., & Glickman N. S. (2006). Demographics, psychiatric diagnoses, and other characteristics of North American Deaf and hard-of-hearing inpatients. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 11(3), 303–321. 10.1093/deafed/enj042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake D. D., Weathers F. W., Nagy L. M., Kaloupek D. G., Gusman F. D., Charney D. S., & Keane T. M (1995). The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8(1), 75–90. 10.1007/BF02105408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer B. A. (1993). Adequacy of a translation of the MMPI into American Sign Language for use with deaf individuals: Linguistic equivalency issues. Rehabilitation Psychology, 38(4), 247–260. 10.1037/h0080302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., & Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damianakis T., & Woodford M. R. (2012). Qualitative research with small connected communities: generating new knowledge while upholding research ethics. Qualitative health research, 22(5), 708–718. 10.1177/1049732311431444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Feu M., & Fergusson K. (2003). Sensory impairment and mental health. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9, 95–103. 10.1192/apt.9.2.95 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fellinger J., Holzinger D., & Pollard R. Q. (2012). Mental health of deaf people. Lancet, 379(9820), 1037–1044. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61143-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellinger J., Holzinger D., Schoberberger R., & Lenz G. (2005). [Psychosocial characteristics of deaf people: evaluation of data from a special outpatient clinic for the deaf]. Der Nervenarzt, 76(1), 43–51. 10.1007/s00115-004-1708-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E. B., Riggs D. S., Dancu C. V., & Rothbaum B. O. (1993). Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13, 181–191. 10.1002/jts.2490060405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E. B., & Tolin D. F. (2000). Comparison of the PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview Version and the Clinician-Administered PTSD scale. Journal of traumatic stress, 13(2), 181–191. 10.1023/A:1007781909213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallaudet Research Institute (2003). Literacy and deaf students. Retrieved from http://gri.gallaudet.edu/Literacy/ - reading

- George S., Duran N., & Norris K. (2014). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. American journal of public health, 104(2), e16–e31. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman N. S. (2013. a). Introduction: what is deaf mental health care? In Glickman N. S.(Ed.), Deaf mental health care (pp. 1–36). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Glickman N. S. (2013. b). Lessons learned from 23 years on a deaf psychiatric inpatient unit In Glickman N. S.(Ed.), Deaf mental health care (pp. 37–68). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Glickman N. S., & Pollard R. Q. (2013). Deaf mental health research: Where we've been and where we hope to go In Glickman N. S.(Ed.), Deaf mental health care (pp. 358–388). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gray M. J., Litz B. T., Hsu J. L., & Lombardo T. W. (2004). Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment, 11(4), 330–341. 10.1177/1073191104269954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton J. (2008). Secondary analysis of qualitative data: An overview. Historical Social Research, 33(3), 33–45. doi:http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-191439 [Google Scholar]

- Hembree E. A., Foa E. B., & Feeny N. C. (2002). Manual for the administration and scoring of the PTSD Symptom Scale - Interview (PSS-I). Retrieved from https://www.istss.org/ISTSS_Main/media/Documents/PSSIManualPDF1.pdf

- Institute of Medicine (2004). Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B. A., Schulz A. J., Parker E. A., & Becker A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual review of public health, 19, 173–202. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H. C., Wilson G. T., Fairburn C. G., & Agras W. S. (2002). Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of general psychiatry, 59(10), 877–883. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R. A. (1998). Analyzing and reporting focus group results. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kvam M. H., Loeb M., & Tambs K. (2007). Mental health in deaf adults: symptoms of anxiety and depression among hearing and deaf individuals. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 12(1), 1–7. 10.1093/deafed/enl015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd P. (2003). Understanding deaf culture: in search of deafhood. Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Lane H. (1992). The mask of benevolence: Disabling the deaf community. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lane H. (2005). Ethnicity, ethics, and the deaf-world. Journal of deaf studies and deaf education, 10(3), 291–310. 10.1093/deafed/eni030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung M. W., Yen I. H., & Minkler M. (2004). Community based participatory research: a promising approach for increasing epidemiology's relevance in the 21st century. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(3), 499–506. 10.1093/ije/dyh010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine E. (1977). The preparation of psychological service providers to the deaf: A report of the Spartanburg Conference on the Functions, Competencies and Training of Psychological Service Providers to the Deaf (Vol. Monograph No. 4). Silver Spring, MD: Professional Rehabilitation Workers with the Adult Deaf.

- Livermore G., Whalen D., Prenovitz S., Aggarwal R., & Bardos M. (2011). Disability data in national surveys: Prepared for the Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/disability-data-national-surveys

- Long-Sutehall T., Sque M., & Addington-Hall J. (2010). Secondary data analysis of qualitative data: A valuable method for exploring sensitive issues with an elusive population. Journal of Research in Nursing, 16(4), 335–344. 10.1177/1744987110381553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen E., & Anton-Culver H. (1988). The medical communication of deaf patients. The Journal of family practice, 26(3), 289–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M. M., Barnett S. L., Block R. C., & Pearson T. A. (2011). Impact of communication on preventive services among deaf American Sign Language users. American journal of preventive medicine, 41(1), 75–79. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M. M., & Paasche-Orlow M. K. (2012). Health literacy and the disenfranchised: the importance of collaboration between limited English proficiency and health literacy researchers. Journal of health communication, 17(Suppl 3), 7–12. doi:10.1080/10810730.2012.712627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M. M., Paasche-Orlow M. K., Winters P. C., Fiscella K., Zazove P., Sen A., Pearson T. (2015). Assessing Health Literacy in Deaf American Sign Language Users. Journal of health communication, 20 (Suppl 2), 92–100. doi:10.1080/10810730.2015.1066468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M. M., Schlehofer D., & Thew D. (2013). Ethical issues in conducting research with deaf populations. American journal of public health, 103(12), 2174–2178. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R., Young T., Bachleda B., & Karchmer M. (2006). How many people use ASL in the United States? Why estimates need updating. Sign Language Studies, 6, 306–335. 10.1353/sls.2006.0019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myklebust H. (1964). The psychology of deafness. New York, NY: Grune and Stratton. [Google Scholar]

- Najavits L. M. (2002). Seeking Safety: a treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Najavits L. M., & Anderson M. L. (2015). Psychosocial treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder In Nathan P. E.& Gorman J. M.(Eds.), A guide to treatments that work (4th Ed, pp. 571–592). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Najavits L. M., Ryngala D., Back S. E., Bolston E., Mueser K. T., & Brady K. T. (2008). Treatment for PTSD and comorbid disorders: a review of the literature In Foa E. B., Keane T. M., Friedman M. J., & Cohen J. A.(Eds.), Effective treatments for PTSD: practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (2nd ed). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- NASMHPD (2012). Proceedings from NASMHPD Deaf Mental Health Research Priority-Consensus Planning Conference: Final list of 34 research priorities Retrieved from http://www.nasmhpd.org/docs/NCMHDI/NASMHPD_Deaf_Mental_Health_Research_Priority_Consensus_Planning_Conference_34 Priorities.pdf.

- Patterson N., & Baines D. (2005). The psycho-social influences affecting the length of hospital stay for deaf mental health service users. Paper presented at the 3rd Mental Health and Deafness World Congress, Worcester, South Africa.

- Pintner R., Eisenson J., & Stanton M. (1941). The psychology of the physically handicapped. New York, NY: Croffs and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard R. Q. (1992. a). 100 years in psychology and deafness: A centennial retrospective. Journal of the American Deafness and Rehabilitation Asssociation, 26(3), 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard R. Q. (1992. b). Cross-cultural ethics in the conduct of deafness research. Rehabilitation Psychology, 37(2), 87–101. 10.1037//0090-5550.37.2.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard R. Q. (2002). Ethical conduct in research involving deaf people In Gutman V.(Ed.), Ethics in mental health and deafness (pp. 162–178). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard R. Q., & Barnett S. (2009). Health-related vocabulary knowledge among deaf adults. Rehabilitation Psychology, 54(2), 182–185. 10.1037/a0015771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard R. Q., Dean R. K., O'Hearn A., & Haynes S. L. (2009). Adapting health education material for deaf audiences. Rehabilitation Psychology, 54(2), 232–238. 10.1037/a0015772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J. L., & Williams L. M. (2011). Auditory status and experiences of abuse among college students. Violence and Victims, 26(6), 788–798. 10.1891/0886-6708.26.6.788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendon M. E. (1992). Deaf culture and alcohol and substance abuse. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 9(2), 103–110. 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90076-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA (2011). Substance use disorders in people with physical and sensory disabilities. In Brief, 6(1). [Google Scholar]

- Schild S., & Dalenberg C. J. (2012). Trauma exposure and traumatic symptoms in deaf adults. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(1), 117–127. 10.1037/a0021578 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr P. P. (2014). A guide to the literature on partial PTSD. PTSD Research Quarterly, 25(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Sebald A. M. (2008). Child abuse and deafness: an overview. American Annals of the Deaf, 153(4), 376–383. 10.1353/aad.0.0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton J. L., Jones G., & Hanumantha S. (2012). Deaf friendly research? Toward ethical practice in research involving deaf particpants. Deaf Studies Digital Journal, (3), http://dsdj.gallaudet.edu/index.php?issue=4§ion_id=2&entry_id=123. [Google Scholar]

- Stein C. H., & Mankowski E. S. (2004). Asking, witnessing, interpreting, knowing: conducting qualitative research in community psychology. American journal of community psychology, 33(1-2), 21–35. 10.1023/B:AJCP.0000014316.27091.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg A. G., Sullivan V. J., & Loew R. C. (1998). Cultural and linguistic barriers to mental health service access: the deaf consumer's perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(7), 982–984. 10.1176/ajp.155.7.982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman A. E., & Brauer B. A. (1999). On being a psychotherapist with deaf clients In Leigh I. W.(Ed.), Psychotherapy with deaf clients from diverse groups (pp. 3–22). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. (1998). Ethical and representational issues in qualitative secondary analysis. Qualitative health research, 8(4), 547–555. 10.1177/104973239800800408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus J. C., Schiller J. A., & Guthmann D. (2008). Characteristics of youths with hearing loss admitted to substance abuse treatment. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 13(3), 336–350. 10.1093/deafed/enm068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon M. (1995). An historical perspectice on psychology and deafness. JADARA, 29(2), 8–13. [redacted for anonymity]. (under review). Deaf people's help-seeking following trauma: Experiences with and recommendations for the behavioral healthcare system. [Google Scholar]