Monoamine oxidase (MAO) is an enzyme responsible for metabolism of monoamine neurotransmitters which play an important role in brain development and function.

Monoamine oxidase (MAO) is an enzyme responsible for metabolism of monoamine neurotransmitters which play an important role in brain development and function.

Abstract

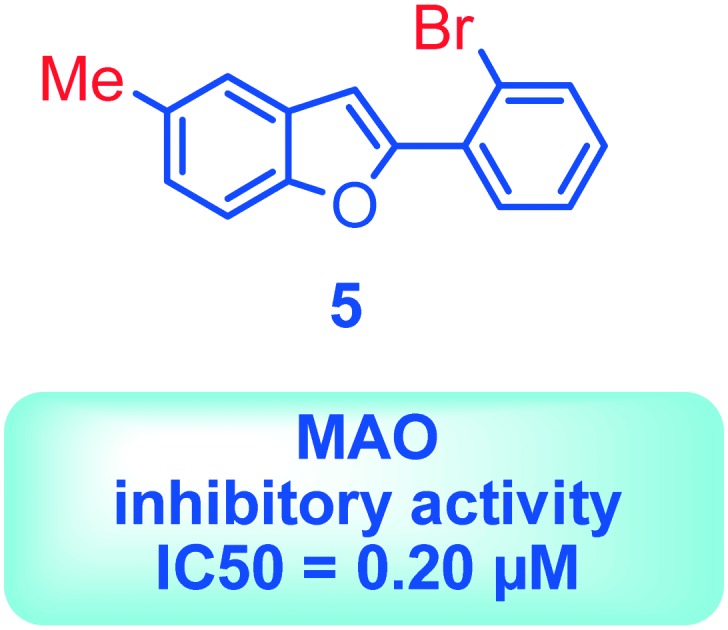

Monoamine oxidase (MAO) is an enzyme responsible for metabolism of monoamine neurotransmitters which play an important role in brain development and function. This enzyme exists in two isoforms, and it has been demonstrated that MAO-B activity, but not MAO-A activity, increases with aging. MAO inhibitors show clinical value because besides the monoamine level regulation they reduce the formation of by-products of the MAO catalytic cycle, which are toxic to the brain. A series of 2-phenylbenzofuran derivatives was designed, synthesized and evaluated against hMAO-A and hMAO-B enzymes. A bromine substituent was introduced in the 2-phenyl ring, whereas position 5 or 7 of the benzofuran moiety was substituted with a methyl group. Most of the tested compounds inhibited preferentially MAO-B in a reversible manner, with IC50 values in the low micro or nanomolar range. The 2-(2′-bromophenyl)-5-methylbenzofuran (5) was the most active compound identified (IC50 = 0.20 μM). In addition, none of the studied compounds showed cytotoxic activity against the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. Molecular docking simulations were used to explain the observed hMAO-B structure–activity relationship for this type of compounds.

Introduction

Monoamine oxidase (MAO) is an enzyme responsible for metabolism of monoamine neurotransmitters. This enzyme plays an important role in brain development and function, so MAO inhibitors are demonstrating great potential as therapeutic agents.1

The MAO enzyme exists in two isoforms, MAO-A and MAO-B. MAO-A metabolizes serotonin in the central nervous system, and inhibitors of this isoform such as phenelzine, isocarboxazid, tranylcypromine, and moclobemide are clinically used for the treatment of depression. On the other hand, the MAO-B isoform is the main isoform responsible for the central dopamine metabolism, so MAO-B inhibitors such as selegiline and rasagiline are used for the treatment of Parkinson's disease (PD).2

In addition, it has been shown that the brain activity of MAO-B increases with age, which does not happen with MAO-A.3 Therefore, besides regulation of monoamine levels, MAO-B inhibitors also have clinical importance because they reduce the formation of by-products of the MAO catalytic cycle such as hydrogen peroxide and aldehyde species.4 These products are toxic, particularly to the brain when they are not rapidly metabolized by glutathione peroxidase and aldehyde-metabolizing enzymes, respectively.5 Moreover, the problem is compounded because these enzymes may be dysfunctional in conditions such as PD, corroborating the theory that excessive MAO activity may result in neurotoxicity and thus contribute to the degenerative process.6 Increased MAO-B levels have also been observed in plaque-associated astrocytes in the brains of Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients and elevation in hydroxyl radicals (˙OH) has been correlated with Aβ plaque formation.7 Therefore, selegiline is being successfully used in AD.8

Over the years, a large number of heterocyclic scaffolds have been exploited to design inhibitors targeting MAOs.9,10 Additionally, reports of the crystal structures of both MAO isoforms by Binda et al. have provided relevant information about the selective interactions and the pharmacophoric requirements needed for the design of potent and selective inhibitors.11–13 Benzofuran (oxygen heterocycle) is a common moiety found in many biologically active natural and therapeutic products, and thus represents a very important pharmacophore. It is present in many medicinally important compounds that show biological activity, including anticancer and antiviral properties.14 Some benzofuran derivatives are also known as 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors, antagonists of the angiotensin II receptor, blood coagulation factor Xa inhibitors, ligands of adenosine A1 receptor14,15 and more recently as MAO inhibitors.16–20 In general, benzofurans described as MAO inhibitors have a higher selectivity to the MAO-B isoform. In our efforts to contribute to the development of novel compounds that may be useful in the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders such as PD or AD, we are focusing on 2-arylbenzofuran derivatives.20 2-Arylbenzofurans have been selected by analogy to 3-phenylcoumarins previously described by us as potent and selective MAO-B inhibitors, and preserving the core of trans-stilbene in their structure.21,22 However, 3-arylcoumarins have been more active than 2-arylbenzofurans described so far. Among the studied benzofuran series, 5-nitro-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)benzofuran has been the most active compound, presenting MAO-B selectivity and reversible inhibition (IC50 = 140 nM).20,23 Based on these previous experimental results, and with the aim of finding novel and more selective MAO-B inhibitors, herein we continue our studies, describing the synthesis, biological evaluation and docking studies of a new series of 2-phenylbenzofuran derivatives. Considering that a bromine atom in the benzofuran leads to non-active derivatives, in this paper we study the influence on the activity of a bromine atom located in different positions of the 2-phenyl in addition to the presence of a methyl group at positions 5 or 7 of the benzofuran ring, which have been revealed as adequate positions for substitution.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

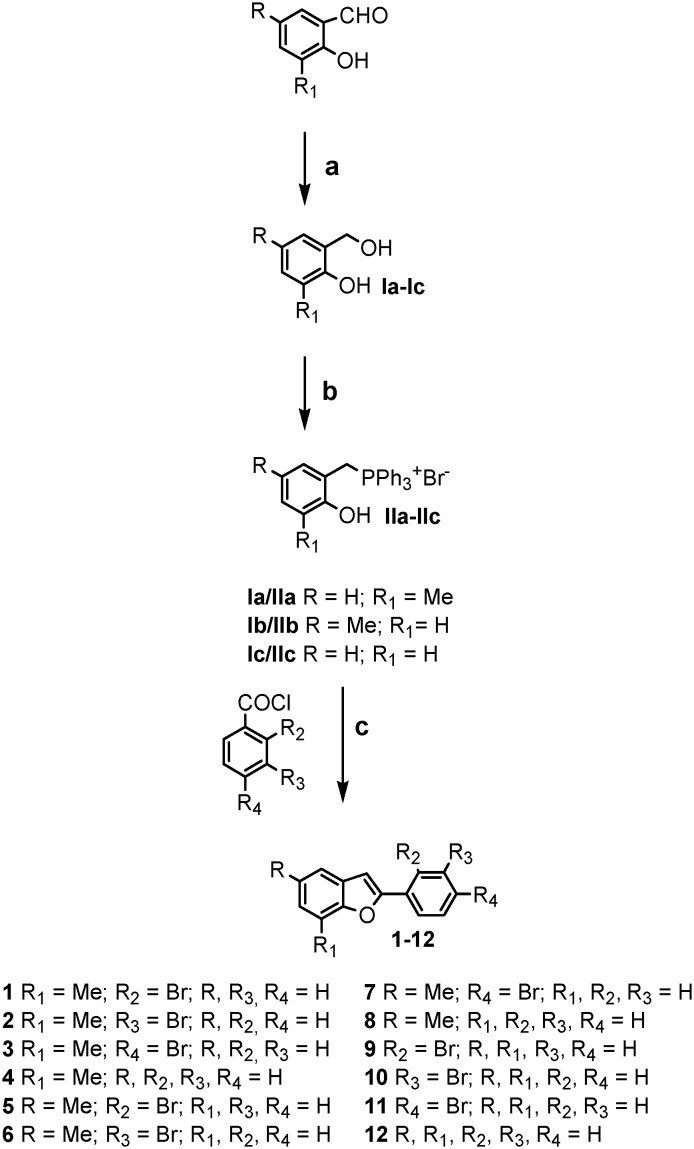

Benzofuran derivatives 1–12 were efficiently synthesized by a Wittig reaction, according to the protocol outlined in Scheme 1. The desired Wittig reagents were readily prepared from the conveniently substituted ortho-hydroxybenzyl alcohols Ia–Ic24–26 and PPh3·HBr.20,24,27 The key step for the formation of the benzofuran moiety was achieved by an intramolecular reaction between the ortho-hydroxybenzyltriphosphonium salt IIa–IIc and the appropriate benzoyl chloride.28–30 The benzofuran structures were confirmed by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, mass spectrometry and elemental analyses.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 2-phenylbenzofuran derivatives via a Wittig reaction. Reagents and conditions: a) NaBH4, EtOH, 0 °C to rt, 2 h; b) PPh3 HBr, CH3CN, 82 °C, 2 h; c) toluene, Et3N, 110 °C, 2 h.

Pharmacology

MAO in vitro inhibition

The potential effects of the synthesized compounds 1–12 on hMAO activity were investigated by measuring the production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) from p-tyramine, using the Amplex Red MAO assay kit (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oregon, USA) and MAO isoforms prepared from insect cells (BTI-TN-5B1-4) infected with recombinant baculovirus containing cDNA inserts for hMAO-A or hMAO-B (Sigma-Aldrich Química S.A., Alcobendas, Spain).

The inhibition of hMAO activity was evaluated following a general procedure previously described.31 The test compounds did not show any interference with the reagents used for the biochemical assay. The control activity of hMAO-A and hMAO-B using p-tyramine as the common substrate was 165 ± 2 pmol of p-tyramine oxidized to p-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde per minute (n = 20).

The results of the hMAO-A and hMAO-B inhibition studies with our compounds and the MAO-B selectivity index are reported in Table 1. Enzymatic assays revealed that most of the test compounds were moderate to potent hMAO inhibitors at either low micromolar to nanomolar concentrations, showing selectivity toward the hMAO-B isoform.

Table 1. IC50 values and MAO-B selectivity index (SI) [IC50 (MAO-A)]/[IC50 (MAO-B)] for the inhibitory effects of test drugs (new compounds and reference inhibitors) on the enzymatic activity of human recombinant MAO isoforms expressed in baculovirus infected BTI insect cells.

| Compound | IC50 hMAO-A (μM) | IC50 hMAO-B (μM) | S.I. |

| 1 | (44.80 ± 1.28) % a | 9.68 ± 0.59 b | ≈11.5 c |

| 2 | >100 | 3.98 ± 0.27 b | >25.2 c |

| 3 | (46.75 ± 1.33) % a | 0.95 ± 0.07 b | ≈95.2 c |

| 4 | (53.85 ± 1.54) % a | 10.73 ± 0.72 b | ≈9.3 c |

| 5 | 10.99 ± 0.73 | 0.20 ± 0.01 b | 55.0 |

| 6 | >100 | 0.25 ± 0.02 b | >400 c |

| 7 | >100 | (46.15 ± 2.07) % a | — |

| 8 | >100 | 0.88 ± 0.06 b | >113.6 c |

| 9 | 8.12 ± 0.54 | 1.13 ± 0.08 b | 7.2 |

| 10 | (50.95 ± 1.46) % a | 1.17 ± 0.08 b | ≈85.5 c |

| 11 | >100 | 0.34 ± 0.02 b | >294.1 c |

| 12 | >100 | >100 | — |

| Clorgyline | 0.0052 ± 0.00092 | 63.41 ± 1.20 b | 0.000082 |

| R-(–)-Deprenyl | 68.73 ± 4.21 | 0.017 ± 0.0019 b | 4.043 |

| Moclobemide | 361.38 ± 19.37 | >1000 | <0.36 c |

aIn brackets, percentage of inhibition at 100 μM concentration. For these derivatives, the IC50 is around 100 μM.

bLevel of statistical significance: P < 0.01 versus the corresponding IC50 values obtained against MAO-A, as determined by ANOVA/Dunnett's.

cValues obtained under the assumption that the corresponding IC50 against MAO-A or MAO-B is the highest concentration tested (100 μM or 1 mM).

Considering the IC50 values obtained for MAO-B activity, these results justify the interest in these compounds.

Reversibility

Reversibility experiments were performed to evaluate the type of inhibition exerted by derivatives 5 and 6, the most potent MAO-B inhibitors in this series.

An effective dilution method was used, and selegiline (irreversible inhibitor) and isatin (reversible inhibitor) were taken as standards.32,33 Compounds 5 and 6 were shown to be reversible hMAO-B inhibitors but their reversibility degree is lower than that shown by isatin (Table 2).

Table 2. Reversibility results of hMAO-B inhibition for derivatives 5 and 6 and reference inhibitors.

| Comp | Slope a (ΔUF/t) [%] |

| 5 | 30.5 ± 2.26 |

| 6 | 30.2 ± 2.03 |

| Selegiline | 11.40 ± 0.76 |

| Isatin | 88.63 ± 5.94 |

aValues represent the mean ± SEM of n = 3 experiments relative to the control; data show recovery of hMAO-B activity after dilution.

Cytotoxicity

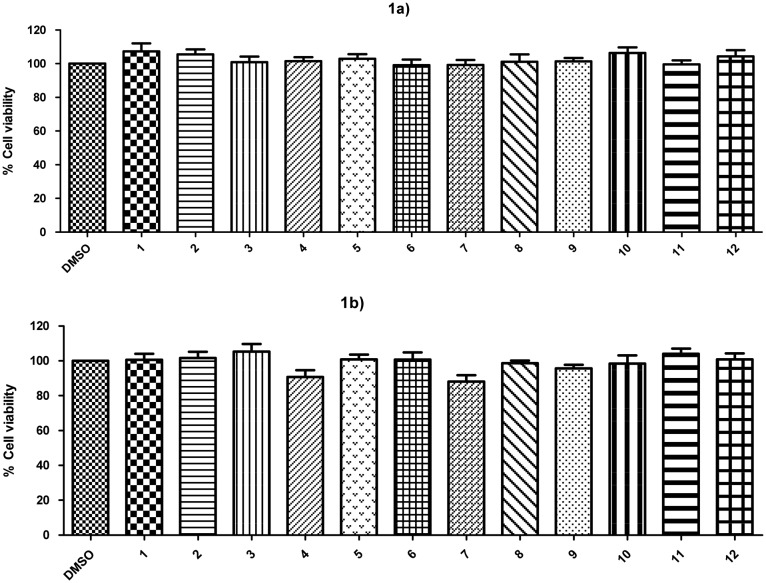

The cytotoxic effects of two concentrations (1 and 10 μM) of compounds 1–12 were evaluated by using the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. Compounds were incubated at 1 μM or 10 μM and maintained for 24 h in the cell culture. Afterward, the percentage of cell viability was measured as MTT reduction.34

As depicted in Fig. 1, none of the compounds (at 1 or 10 μM concentration) significantly decreased the viability of SH-SY5Y cells.

Fig. 1. Cytotoxic activity after 24 h incubation with compounds 1–12 at 1 μM concentration (1a) or 10 μM concentration (1b) on SH-SY5Y cells. Cell viability was measured as MTT reduction and data were normalized as % of control treated with 1% DMSO. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M from at least 5 different cultures. No statistical differences were found with the control group using the one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test.

Docking calculations

Molecular docking simulations were performed using the Schrödinger package (Glide extra precision).35 We downloaded the crystallized structure of the hMAO-B (; 2V60)36 from the Protein Data Bank. We performed docking simulations following two protocols. In protocol 1, only a water molecule (HOH1159) that establishes an H-bond with the co-crystallized ligand is retained. In protocol 2, we retained in the pocket the water molecules in a distance of 5 Å from the ligand. Geometrical quality of the docking with Glide was previously validated in the hMAO-B (more details in the Methods section).37–39

Prediction of ADME properties

Theoretical calculations were also performed using the Molispiration property program40 to predict some physicochemical and ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion) parameters of the target compounds and compare with reference inhibitors. The values of predicted parameters, including lipophilicity, expressed as log P, molecular weight (MW), topological polar surface area (TPSA), number of hydrogen donors (nON), number of hydrogen bond acceptors (nOHNH) and molecular volume, are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Structural properties of 2-phenylbenzofuran derivatives 1–12 and reference compounds.

| Compound | log P a | TPSA b (Å2) | MW c (da) | nOH d | nOHNH d | Volume e | Lipinski f |

| 1 | 5.34 | 13.14 | 287.16 | 1 | 0 | 215.46 | 1 |

| 2 | 5.37 | 13.14 | 287.16 | 1 | 0 | 215.46 | 1 |

| 3 | 5.39 | 13.14 | 287.16 | 1 | 0 | 215.46 | 1 |

| 4 | 4.58 | 13.14 | 208.26 | 1 | 0 | 197.57 | 0 |

| 5 | 5.37 | 13.14 | 287.16 | 1 | 0 | 215.46 | 1 |

| 6 | 5.39 | 13.14 | 287.16 | 1 | 0 | 215.46 | 1 |

| 7 | 5.42 | 13.14 | 287.16 | 1 | 0 | 215.46 | 1 |

| 8 | 4.61 | 13.14 | 208.26 | 1 | 0 | 197.57 | 0 |

| 9 | 4.94 | 13.14 | 273.13 | 1 | 0 | 198.90 | 0 |

| 10 | 4.97 | 13.14 | 273.13 | 1 | 0 | 198.90 | 0 |

| 11 | 4.99 | 13.14 | 273.13 | 1 | 0 | 198.90 | 0 |

| 12 | 4.18 | 13.14 | 194.23 | 1 | 0 | 181.01 | 0 |

| R-(–)-Deprenyl | 2.64 | 3.24 | 187.29 | 1 | 0 | 202.64 | 0 |

| Rasagiline | 2.10 | 12.03 | 171.24 | 1 | 1 | 175.10 | 0 |

alog P – expressed as the logarithm of the octanol/water partition coefficient.

bTPSA – topological polar surface area.

cMW – molecular weight.

dNumber of hydrogen bond acceptors (nOH) and donors (nOHNH).

eMolecular volume.

fNumber of violations of Lipinski's rules.

From the data presented in Table 3, it is significant to highlight that all the compounds described possess log P values compatible with those required to cross membranes. Although some of the compounds such as 1–3 and 5–7 show log P values slightly higher than 4, log P values in the –0.4 to +5.6 range41 are acceptable and all the designed compounds have a log P in this range. In addition, MAO inhibitors have to pass the BBB and this log P value could improve the penetration in the CNS.

TPSA, described to be a predictive indicator of membrane penetration, was found to be positive for all the compounds.

As Lipinski's rule states that, in general, an orally active drug has no more than one violation of the parameters above described, these data suppose important information about the potential drug-likeness of these new bromo-2-phenylbenzofurans.

Discussion

Compounds 1–12 were efficiently synthesized by a reaction of ortho-hydroxybenzyltriphosphonium salts and the appropriate benzoyl chlorides.

The experimental activity results showed that most of the test compounds are selective MAO-B inhibitors in the low micro or nanomolar range. Activity results for the most potent derivatives in this series are similar to those most potent previously described by us.20

As a rule, 2-phenylbenzofurans substituted at the 5-position were found to be more active molecules as MAO-B inhibitors than the corresponding 7-methyl-substituted derivatives or those derivatives unsubstituted in the benzene ring except for derivatives bearing a bromine atom in the para position of the 2-phenyl ring.

Considering that 2-phenylbenzofurans with a bromine atom at position 5 in the benzofuran ring were inactive,20 the obtained results point out that the location of this substituent is at least as important as its nature for the activity.

In addition, in comparison to the previously obtained data,20,23 while the methoxy substituent in the para position on the 2-aryl leads to the best results, when that substituent is exchanged for a bromine atom, the ortho and meta positions are more favorable for the substitution.

Benzofurans 5 and 6 bearing a bromine atom in ortho or meta positions, respectively, of the 2-phenyl ring, were the most active hMAO-B inhibitors of the described series. In general, the presence of a bromine atom on the 2-phenyl ring improves the MAO-B activity of these derivatives. Based on the experimental results, we performed molecular docking calculations with Glide39 in the hMAO-B crystal structure (PDB code: ; 2V60)36 to obtain detailed information on the key interactions and preferred binding modes adopted by the compounds. Docking protocol and validation are explained with more details in the Methods section and in previous research developed by our group.37–39,42

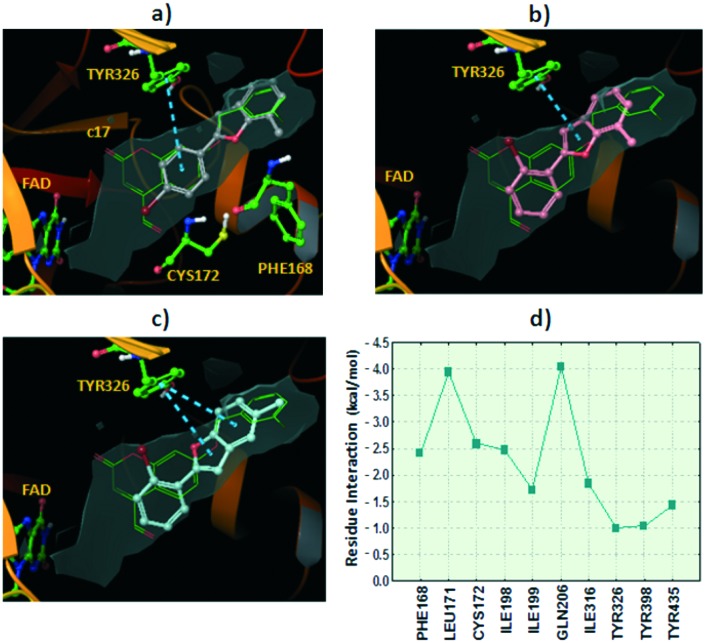

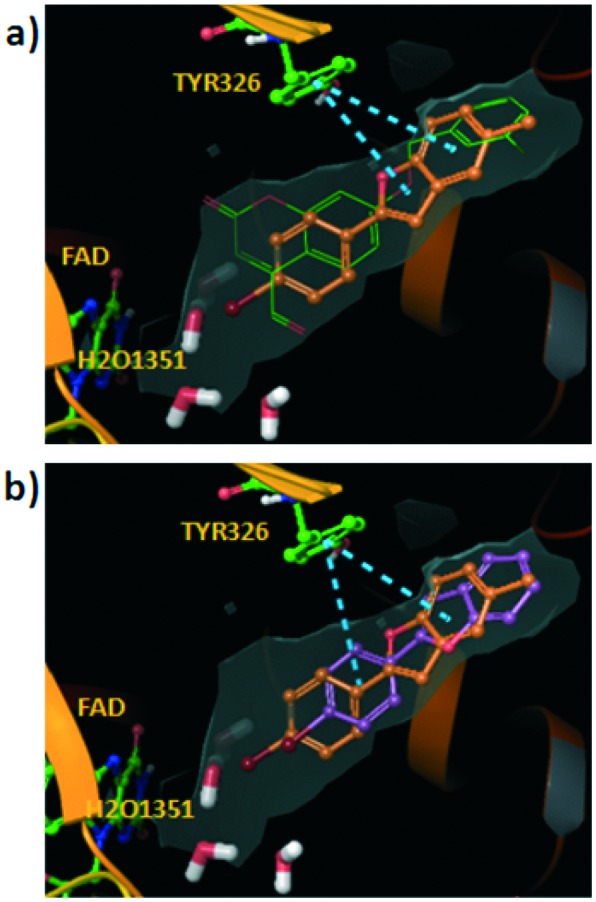

Docking simulations showed two alternative binding solutions for the analyzed compounds. Compounds adopted a conformation where the benzofuran moiety occupies the hydrophobic entrance cavity whereas the 2-phenyl is oriented towards the catalytic cleft. An alternative and inverted binding mode was detected for some compounds in which the 2-phenyl is placed in the hydrophobic cavity and the benzofuran is oriented towards the FAD cofactor. However, additional docking simulations retaining water molecules in the hMAO-B pocket pointed out the first described binding mode as the preferred binding solution. Similar binding patterns were found for a structurally related set of compounds in a previous study by our group.20 It is worth noting that the similar compound 2-(2-benzofuranyl)-2-imidazoline in the crystallized 2XFN hMAO-B structure42 is bound in a distinct side of the substrate-binding cavity with H-bonds with Pro102 and Tyr326. Although our docking reproduced with reliability the crystallized binding in 2XFN, the simulations did not yield any pose for our compounds in the same 2XFN binding area. The binding mode for the most active compound in the 7-methyl benzofuran series, compound 3, is shown in Fig. 2a, where the benzofuran moiety occupies the hydrophobic entrance cavity whereas the 2-phenyl is oriented towards the catalytic site. The compound placed the 7-methyl substituent in the same hydrophobic area where the co-crystallized coumarin c17 (Fig. 3) positioned the chlorine atom at the meta position of the phenyl ring. Fig. 2a shows the superposition of both poses (compound 3 and co-crystallized c17) along with the hydrophobic surface calculated inside the hMAO-B.

Fig. 2. Hypothetical binding modes for the studied compounds extracted from the docking in the hMAO-B. The co-crystallized coumarin c17 (; 2V60) is also shown for comparative purposes (green carbons). The hydrophobic surface in the pocket is represented in grey color. π–π stacking interactions with residue Tyr326 are represented in blue dashed lines. Ribbons in the protein are partially omitted for clarity. a) Binding mode for compound 3 (grey carbons). b) Pose determined for compound 1 (pink carbons). c) Pose extracted from docking for compound 5 (turquoise carbons). d) Residue interaction contributions for the binding with compound 5 (sum of Coulomb, van der Waals and hydrogen bond energies).

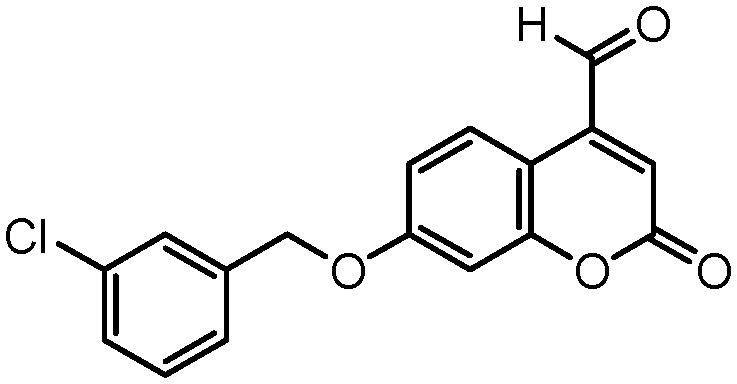

Fig. 3. Chemical structure of c17 (7-(3-chlorobenzyloxy)-4-carboxaldehydecoumarin).

The pose of compound 3 was stabilized through π–π stacking interactions between the residue Tyr326 and the 2-phenyl scaffold in the ligand. The other compounds in the series with 7-methyl substitution showed lower hMAO-B activity. In fact, as an example, compound 1 with bromine at the ortho position yielded a similar binding mode but slightly shifted towards the catalytic cleft and with the consequent disruption of some hydrophobic interactions with the entrance cavity (see Fig. 2b).

Compounds 5 and 6, the most active compounds in the studied series, yielded similar binding modes pointing the 5-methyl towards the hydrophobic entrance cavity. The benzofuran is also slightly shifted towards the catalytic cleft compared to compound 3.

However, in this case the shift allows accommodating the 5-methyl substituent in the hydrophobic area (see Fig. 2c with the pose described for compound 5). We calculated the contribution of the different residues of the pocket to the interaction with compound 5 (see Fig. 2d). Key residues in ligand recognition are Gln206, Leu171, Cys172, Ile198 and Phe168.

Compound 7, with a bromine substituent at the para position of the 2-phenyl ring, showed a drastic loss of hMAO-B activity. Molecular docking showed two alternatives to explain the decreased binding affinity. Docking with water molecules in the pocket (protocol 2, see the Methods section) yielded a pose for compound 7 with the benzofuran oriented towards the FAD cofactor and the 2-phenyl pointing towards the hydrophobic entrance cavity. Disruption of the preferred binding mode could influence the ligand binding energy.

In the second binding alternative provided by docking with a water molecule in the pocket (protocol 1), the compound maintained the preferred binding mode but the bromine substituent in the 2-phenyl ring is placed very close to an area that would be occupied with a water molecule (HOH1351) in the hMAO-B crystallized structure (distance between the bromine and oxygen atoms is 1.39 Å, see Fig. 4a). The proposed binding mode causes the displacement of the HOH1351 water molecule by the bromine atom. This process could be energetically expensive for the formation of the ligand–protein complex. Moreover, compound 11 showed a binding solution with the benzofuran placed in a similar area to compound 3 and with the bromine substituent in a larger distance from the catalytic cleft, compared to compound 7 (see Fig. 4b). Due to the better accommodation in the pocket, compound 11 showed also good inhibitory effect values in the hMAO-B.

Fig. 4. a) Hypothetical binding mode calculated for compound 7 inside the hMAO-B (the co-crystallized coumarin c17 in green color is shown for comparative purposes. Blue dashed lines represent π–π stacking interactions). However, for this binding mode to occur, compound 7 should displace the water molecule HOH1351 present in the crystallized hMAO-B protein. This fact could negatively affect the complex formation. Although different water molecules in the pocket are shown, the pose was extracted from docking performed using protocol 1 with only the water molecule HOH1159 retained in the pocket. b) Comparison between the poses determined by docking for compounds 7 and 11. Compound 11 is shifted towards the hydrophobic entrance cavity and the bromine substituent is farther from the water molecules placed in the catalytic site.

The fact that at least the most potent compounds (5 and 6) inhibit MAO-B reversibly and that none have toxic effects at active concentrations, makes these derivatives may be of interest for further studies.

Experimental

The general synthetic procedures and spectral data for all are given below.

General methods

Starting materials and reagents were obtained from commercial suppliers and were used without further purification. Melting points (mp) are uncorrected and were determined with a Reichert Kofler thermopan or in capillary tubes in a Buchi 510 apparatus. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian INOVA 500 spectrometer using DMSO-d6 or CDCl3 as the solvent. Chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in parts per million (ppm) using TMS as an internal standard. Coupling constants J are expressed in hertz (Hz). Spin multiplicities are given as s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet) and m (multiplet). Mass spectrometry was carried out with a Kratos MS-50 or a Varian MAT-711 spectrometer. Elemental analyses were performed by using a Perkin-Elmer 240B microanalyzer and were within ±0.4% of calculated values in all cases. The analytical results were ≥95% purity for all compounds. Flash Chromatography (FC) was performed on silica gel (Merck 60, 230–400 mesh); analytical TLC was performed on precoated silica gel plates (Merck 60 F254). Organic solutions were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. Concentration and evaporation of the solvent after the reaction or extraction were carried out on a rotary evaporator (Büchi Rotavapor) operating at reduced pressure.

Synthesis

General procedure for the preparation of 2-hydroxybenzylalcohols

Sodium borohydride (6.60 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of 2-hydroxybenzaldehyde (6.60 mmol), in ethanol (20 mL), in an ice bath. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. After that, the solvent was removed, 1 N aqueous HCl solution (40 mL) was added to the residue and extracted with diethyl ether. The solvent was evaporated under vacuum to give the desired compounds Ia–Ic.24–26

General procedure for the preparation of 2-hydroxybenzyltriphenylphosphonium bromide

A mixture of 2-hydroxybenzylalcohol (16.27 mmol) and PPh3·HBr (16.27 mmol) in CH3CN (40 mL) was stirred under reflux for 2 h. The solid formed was filtered and washed with CH3CN to give the desired compounds IIa–IIc.20,24,27

General procedure for the preparation of 2-phenylbenzofuran 1–12

A mixture of 2-hydroxybenzyltriphenylphosphonium bromide (1.11 mmol) and benzoyl chloride (1.11 mmol) in a mixed solvent (toluene 20 mL and Et3N 0.5 mL) was stirred under reflux for 2 h. The precipitate was removed by filtration. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography (hexane/EtOAc 9 : 1) to give the desired compounds.27–29

2-(2′-Bromophenyl)-7-methylbenzofuran (1)

Yield: 32%; mp: 65–67 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.61 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.10–7.23 (m, 2H, H-3, H-6), 7.27–7.40 (m, 1H, H-5), 7.46 (t, 1H, H-4′, J = 7.6), 7.50 (d, 1H, H-5′, J = 7.4), 7.54 (d, 1H, H-4, J = 1.9), 7.74 (d, 1H, H-6′, J = 8.0), 8.01 ppm (dd, 1H, H-3′, J = 7.9, 1.6); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 15.58, 103.92, 121.19, 122.22, 122.60, 123.33, 126.85, 127.21, 129.10, 129.38, 130.32, 132.92, 135.25, 154.29, 156.32 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 288 (100) [M + 2]+, 286 (97) [M]+, 207 (12), 178 (24); anal. calcd for C15H11BrO: C 62.74; H 3.86, found: C 62.75; H 3.88.

2-(3′-Bromophenyl)-7-methylbenzofuran (2)

Yield: 72%; mp: 44–45 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.63 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.05 (s, 1H, H-3), 7.12–7.20 (m, 2H, H-5, H-6), 7.33 (dd, 1H, H-4, J = 9.9, 5.9), 7.45 (dd, 1H, H-6′, J = 7.6, 0.4), 7.50 (ddd, 1H, H-5′, J = 7.9, 1.9. 0.9), 7.79–7.83 (m, 1H, H-4′), 8.05 ppm (t, 1H, H-2′, J = 1.7); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 15.63, 104.18, 122.02, 122.20, 122.63, 123.35, 125.52, 127.24, 129.30, 129.42, 130.72, 131.42, 132.84, 154.29, 158.12 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 288 (100) [M + 2]+, 286 (97) [M]+, 207 (5), 178 (15), 152 (5); anal. calcd for C15H11BrO: C 62.74; H 3.86, found: C 62.76; H 3.90.

2-(4′-Bromophenyl)-7-methylbenzofuran (3)

Yield: 50%; mp: 66–67 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.61 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.04 (s, 1H, H-3), 7.11–7.19 (m, 2H, H-5, H-6), 7.44 (d, 1H, H-4, J = 7.5), 7.58–7.62 (m, 2H, H-2, H-6), 7.77 ppm (d, 2H, H-3′, H-5′, J = 8.5); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 15.58, 102.75, 122.22, 122.63, 123.35, 124.46, 127.23, 127.50, 129.39, 129.98, 132.10, 154.32, 158.30 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 288 (100) [M + 2]+, 286 (98) [M]+, 206 (10), 178 (15); anal. calcd for C15H11BrO: C 62.74; H 3.86, found: C 62.78; H 3.89.

7-Methyl-2-phenylbenzofuran (4)

30 Yield: 45%; mp: colorless liquid; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.62 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.04 (s, 1H, H-3), 7.11 (d, 1H, H-6, J = 7.2,), 7.16 (t, 1H, H-5, J = 7.5), 7.37 (t, 1H, H-4′, J = 7.4), 7.42–7.51 (m, 3H, H-4, H-3′, H-5′), 7.91 (d, 2H, H-2′, H-6′, J = 7.4); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 15.10, 101.16, 118.30, 121.40, 122.9, 124.90, 125.20, 128.40, 128.65, 128.70, 130.70, 153.85, 155.50 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 208 (100) [M]+, 193 (15), 165 (5); anal. calcd for C15H12O: C 86.51; H 5.81, found: C 86.54; H 5.84.

2-(2′-Bromophenyl)-5-methylbenzofuran (5)

Yield: 22%; mp: 49–51 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.49 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.16 (dd, 1H, H-6, J = 8.4, 1.4), 7.19–7.25 (m, 1H, H-4′), 7.42 (s, 1H, H-3), 7.43–7.46 (m, 2H, H-4, H-5′), 7.49 (d, 1H, H-7, J = 0.7), 7.73 (dd, 1H, H-6′, J = 8.1, 1.1), 7.98 ppm (dd, 1H, H-3′, J = 7.9, 1.7); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 21.30, 101.39, 112.92, 121.20, 123.69, 126.12, 126.93, 127.99, 129.10, 130.33, 132.00, 133.02, 135.26, 155.71, 157.59 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 288 (100) [M + 2]+, 286 (97) [M]+, 207 (12), 178 (23); anal. calcd for C15H11BrO: C 62.74; H 3.86, found: C 62.75; H 3.89.

2-(3′-Bromophenyl)-5-methylbenzofuran (6)

Yield: 22%; mp: 90–94 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.47 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.00 (s, 1H, H-3), 7.14 (d, 1H, H-6, J = 8.3), 7.33 (d, 1H, H-5′, J = 4.1), 7.38–7.44 (m, 2H, H-4, H-7), 7.48 (d, 1H, H-4′, J = 8.9), 7.79 (d, 1H, H-6′, J = 7.8), 8.02 ppm (s, 1H, H-2′); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 21.25, 101.83, 112.93, 122.16, 123.75, 125.53, 126.15, 128.10, 129.52, 130.73, 131.42, 131.99, 132.83, 155.69, 159.47 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 288 (100) [M + 2]+, 286 (97) [M]+, 206 (10), 178 (26), 152 (10); anal. calcd for C15H11BrO: C 62.74; H 3.86, found: C 62.74; H 3.88.

2-(4′-Bromophenyl)-5-methylbenzofuran (7)

Yield: 35%; mp: 195–197 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.47 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.98 (s, 1H, H-3), 7.13 (d, 1H, H-6, J = 8.4), 7.37–7.43 (m, 2H, H-4, H-7), 7.59 (d, 2H, H-2′, H-6′, J = 8.6), 7.74 ppm (d, 2H, H-3′, H-5′, J = 8.6); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 21.25, 100.46, 112.92, 123.69, 124.46, 126.14, 127.52, 127.99, 129.99, 131.82, 132.07, 155.72, 159.83 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 288 (100) [M + 2]+, 286 (98) [M]+, 206 (10), 178 (15); anal. calcd for C15H11BrO: C 62.74; H 3.86, found: C 62.76; H 3.88.

5-Methyl-2-phenylbenzofuran (8)

30 Yield: 55%; mp: 128–130 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.47 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.97 (s, 1H, H-3), 7.11 (d, 1H, H-6, J = 8.3), 7.37 (d, 2H, H-3′, H-5′, J = 7.5), 7.40–7.49 (m, 3H, H-4, H-7, H-4′), 7.84–7.90 ppm (m, 2H, H-2′, H-6′); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 21.28, 101.00, 110.58, 120.64, 124.77, 125.46, 128.33, 128.68, 129.22, 130.53, 132.26, 153.24, 155.89 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 208 (100) [M]+, 193 (25), 165 (10); anal. calcd for C15H12O: C 86.51; H 5.81, found: C 86.53; H 5.85.

2-(2′-Bromophenyl)-benzofuran (9)

30 Yield: 30%; mp: 36–38 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.23 (s, 1H, H-3), 7.28–7.30 (m, 1H, H-4′), 7.32–7.37 (m, 1H, H-5), 7.42–7.47 (m, 1H, H-7), 7.55 (m, 2H, H-6, H-5′), 7.66 (d, 1H, H-6′, J = 7.8), 7.73 (d, 1H, H-4, J = 9.0), 7.99 ppm (dd, 1H, H-3′, J = 7.9, 1.6); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 107.12, 111.15, 120.65, 121.34, 122.80, 124.85, 127.41, 128.82, 129.38, 129.70, 131.30, 134.25, 153.25, 154.29 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 274 (100) [M + 2]+, 272 (97) [M]+, 195 (10), 180 (20); anal. calcd for C14H9BrO: C 61.57; H 3.32, found: C 61.58; H 3.35.

2-(3′-Bromophenyl)-benzofuran (10)

30 Yield: 35%; mp: 83–85 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.07 (s, 1H, H-3), 7.26 (d, 1H, H-4′, J = 7.4), 7.34 (td, 2H, H-5, H-6, J = 8.1, 1.9), 7.44–7.52 (m, 1H, H-7), 7.55 (d, 1H, H-4, J = 8.2), 7.62 (d, 1H, H-6′, J = 7.6), 7.77–7.83 (m, 1H, H-5′), 8.04 ppm (s, 1H, H-2′); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 102.40, 111.22, 121.15, 122.85, 123.20, 123.45, 124.82, 127.75, 128.84, 130.32, 131.30, 134.43, 154.25, 154.84 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 274 (100) [M + 2]+, 272 (98) [M]+, 195 (15), 180 (22); anal. calcd for C14H9BrO: C 61.57; H 3.32, found: C 61.59; H 3.34.

2-(4′-Bromophenyl)-benzofuran (11)

30 Yield: 45%; mp: 158–160 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.05 (s, 1H, H-3), 7.24–7.28 (m, 1H, H-5), 7.34 (td, 1H, H-6, J = 8.0, 3.9), 7.54 (d, 1H, H-7, J = 8.2), 7.58–7.63 (m, 3H, H-4, H-2′, H-6′), 7.72–7.78 ppm (m, 2H, H-3′, H-5′); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 101.82, 111.10, 120.98, 122.47, 123.15, 124.58, 126.32, 129.10, 129.36, 131.92, 154.74, 154.87 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 274 (100) [M + 2]+, 272 (97) [M]+, 195 (12), 180 (25); anal. calcd for C14H9BrO: C 61.57; H 3.32, found: C 61.58; H 3.36.

2-Phenylbenzofuran (12)

30 Yield: 85%; mp: 120–122 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 6.96 (s, 1H, H-3), 7.34–7.15 (m, 3H, H-5, H6, H4′), 7.36–7.43 (m, 2H, H-3′, H-5′), 7.50 (d, 1H, H-7, J = 8.2), 7.58–7.63 ppm (m, 3H, H-4, H-2′, H-6′); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 101.20, 111.16, 120.88, 122.91, 124.24, 124.92, 128.52, 128.77, 129.21, 130.49, 154.89, 155.92 ppm; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 194 (100) [M]+, 166 (45); anal. calcd for C14H10O: C 86.57; H 5.19, found: C 86.60; H 5.23.

Determination of human MAO isoform activity

The effects of the tested compounds on hMAO isoform enzymatic activity were evaluated by a fluorimetric method. Briefly, 0.1 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 7.4) containing the tested drugs in several concentrations and adequate amounts of recombinant hMAO-A or hMAO-B required and adjusted to obtain under our experimental conditions the same reaction velocity [165 pmol of p-tyramine per min (hMAO-A: 1.1 μg of protein; specific activity: 150 nmol of p-tyramine oxidized to p-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde per min per mg of protein; hMAOB: 7.5 μg of protein; specific activity: 22 nmol of p-tyramine transformed per min per mg of protein)] were placed in a dark fluorimeter chamber and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. The reaction was started by adding (final concentrations) 200 μM Amplex Red reagent, 1 U mL–1 horseradish peroxidase and 1 mM p-tyramine. The production of H2O2 and, consequently, of resorufin was quantified at 37 °C in a multidetection microplate fluorescence reader (FLX800TM, Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) based on the fluorescence generated (excitation, 545 nm, emission, 590 nm) over a 15 min period, in which the fluorescence increased linearly.

Control experiments were carried out simultaneously by replacing the tested drugs with appropriate dilutions of the vehicles. In addition, the possible capacity of the above tested drugs for modifying the fluorescence generated in the reaction mixture due to non-enzymatic inhibition (e.g., for directly reacting with Amplex Red reagent) was determined by adding these drugs to solutions containing only the Amplex Red reagent in a sodium phosphate buffer. The specific fluorescence emission (used to obtain the final results) was calculated after subtraction of the background activity, which was determined from vials containing all components except the hMAO isoforms, which were replaced by a sodium phosphate buffer solution.

Reversibility

To evaluate whether compounds 5 and 6 are reversible or irreversible hMAO-B inhibitors, a dilution method was used.32 A 100× concentration of the enzyme used in the above described experiments was incubated with a concentration of inhibitor equivalent to 10-fold the IC50 value. After 30 min, the mixture was diluted 100-fold into a reaction buffer containing Amplex Red reagent, horseradish peroxidase and p-tyramine and the reaction was monitored for 15 min. Reversible inhibitors show linear progress with a slope equal to ≈91% of the slope of the control sample, whereas irreversible inhibition reaches only ≈9% of this slope. A control test was carried out by pre-incubating and diluting the enzyme in the absence of inhibitor.

Cytotoxicity

Cells of the SH-SY5Y cell line, a twice-subcloned cell line derived from the SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cell line (ATCC CRL-2266 – American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, EE.UU) which is used widely in experimental neurological studies such as neurotoxicity and neuroprotection, were grown and kept in culture as described elsewhere.43

For experiments SH-SY5Y cells (1.106 mL–1) were seeded in each well of 96-well culture plate. After overnight incubation, a solution of compounds 1–12 in DMSO (1%) was added to the cells.

Cells treated with DMSO 1% were used as negative control. After further incubation for 24 h, 3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium (MTT) assay was performed to measure cell viability.34

Briefly, 10% of an MTT solution (5 mg ml–1 in PBS) was added to each well. After incubation for 2 h at 37 °C, the MTT solution was removed and 100 μL of DMSO was added to dissolve the crystals formed. Then, absorbance at 540 nm was read using a microplate reader. The percentage cell viability was calculated as [Absorbance (treatment)/Absorbance (negative control)] 100%.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking simulations were performed using the Schrödinger package.35 We downloaded the crystallized structure of the hMAO-B (; 2V60)36 from the Protein Data Bank. The protein is co-crystallized with the ligand 7-(3-chlorobenzyloxy)-4-carboxaldehydecoumarin (c17). We prepared the protein structure through different steps: addition of hydrogens, cap termini, optimization of tautomers and protonation states of the residues, optimization of the H-bonding networks, etc.

Ligands were also pre-processed using LigPrep that generated tautomers, protonation states at neutral pH and optimized molecular structures. We performed docking simulations following two protocols: 1) retaining only a water molecule (HOH1159) that establishes an H-bond with the co-crystallized ligand, and 2) retaining in the pocket water molecules in a distance of 5 Å from the ligand. As a previous step to docking, we generated a receptor grid centered in the co-crystallized ligand in the hMAO-B pocket. We docked the ligands to the protein through Glide extra precision (XP mode).38

Top scoring poses for each ligand were retained as representative of the simulations. Geometrical quality of the docking with Glide was previously validated measuring the RMSD (root mean square deviation) between crystallographic and theoretical docking poses of different ligands bound to the hMAO-B.37–39,42 The RMSD values for some crystallized ligands in the current study are: ; 2V60 (1.52 and 1.53 Å with protocol 1 and 2), 2V61 (1.35 and 0.85 Å with protocol 1 and 2), 2XFN (0.77 and 6.42 Å with protocol 1 and 2).

Conclusions

We have used the Wittig reaction as a key step for the efficient and general synthesis of a series of 2-phenylbenzofuran derivatives. Most of the synthesized benzofurans reversibly inhibited the MAO-B isoenzyme with IC50 values in the low micro or nanomolar range. In addition, all of them showed a high MAO-B selectivity degree.

Substitution at the 5-position of the 2-phenylbenzofuran ring leads to the most potent derivatives. Additionally, the presence of a bromine atom on the 2-phenyl ring improves the MAO-B activity. Compounds 5 bearing a bromine atom in the ortho position of the 2-phenyl ring and a methyl group at the 5-position of the benzofuran resulted as the most active among the tested compounds.

Molecular docking simulations helped in the explanation of the hMAO-B structure–activity relationships of this type of compounds.

None of the compounds were cytotoxic at the studied concentrations and they display good theoretical ADME properties. Therefore, these results encourage us to further studies of this type of benzofuran derivatives.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Consellería de Cultura, Educación e Ordenación Universitaria (EM2014/016 and the Centro Singular de Investigación de Galicia Accreditación 2016–2019, ED431G/05) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) is gratefully acknowledged. Financial support from the Fondazione Banco di Sardegna – Università degli Studi di Cagliari – Progetti di Ricerca di Interesse Dipartimentale (PRID) is also acknowledged. The authors would like to thank “Angeles Alvariño, Plan Galego de Investigación, Innovación e Crecemento 2011–2015 (I2C)”, and the European Social Fund (ESF). G. L. Delogu is grateful to R. Mascia (University of Cagliari) for his technical assistance.

Footnotes

†The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- Ramsay R. R. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012;12:2189. doi: 10.2174/156802612805219978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finberg J. P. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014;143:133. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler J. S., Volkow N. D., Wang G. J., Logan J., Pappas N., Shea C., MacGregor R. Neurobiol. Aging. 1997;18:431. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naoi M., Maruyama W. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010;16:2799. doi: 10.2174/138161210793176527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G. J. Neural Transm., Suppl. 1990;32:229. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9113-2_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Tong Q., Zhang L., Jiang S., Zhou H., Zhang R., Zhang S., Xu Q., Li D., Zhou X., Ding J., Zhang K. Int. J. Neurosci. 2016;126:641. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2015.1054031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler C. J., Wiberg A., Oreland L., Marcusson J., Winblad B. J. Neural Transm.: Gen. Sect. 1980;49:1. doi: 10.1007/BF01249185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaiclav F., Koliba's E. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 1999;24:234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helguera A. M., Perez-Machado G., Cordeiro M. N., Borges F. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2012;12:907. doi: 10.2174/138955712802762301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis J., Encarnação I., Gaspar A., Morales A., Milhazes N., Borges F. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012;12:2116. doi: 10.2174/156802612805220020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda C., Newton-Vinson P., Hubalek F., Edmondson D. E., Mattevi A. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2002;9:22. doi: 10.1038/nsb732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda C., Li M., Hubelek F., Restelli N., Edmondson D. E., Mattevi A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:9750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633804100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Colibus L., Li M., Binda C., Lustig A., Edmondson D. E., Mattevi A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:12684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505975102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Gao B., Huang W., Liang Y., Huang G., Ma Y. Synth. Commun. 2008;39:197. [Google Scholar]

- Galal S. A., Abd El-All A. S., Abdallah M. M., El-Diwani H. I. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:2420. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins L. H. A., Petzer J. P., Malan S. F. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:4458. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldenhuys W. J., Funk M. O., Van der Schyf C. J., Carroll R. T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:1380. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani L., Barletta M., Soto-Otero R., Nicolotti O., Mendez-Alvarez E., Catto M., Introcaso A., Stefanachi A., Cellamare S., Altomare C., Carotti A. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:2651. doi: 10.1021/jm4000769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyk A. S., Petzer J. P., Petzer A., Legoabe L. J. Drug Des., Dev. Ther. 2015;9:5479. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S89961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferino G., Cadoni E., Matos M. J., Quezada E., Uriarte E., Santana L., Vilar S., Tatonetti N. P., Yáñez M., Viña D., Picciau C., Serra S., Delogu G. ChemMedChem. 2013;8:956. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M. J., Terán C., Pérez-Castillo Y., Uriarte E., Santana L., Viña D. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:7127. doi: 10.1021/jm200716y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viña D., Matos M. J., Ferino G., Cadoni E., Laguna R., Borges F., Uriarte E., Santana L. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:464. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carradori S., Silvestri R. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:6717. doi: 10.1021/jm501690r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt B., Riem Ha H., Hesse M. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2002;85:2990. [Google Scholar]

- Ducho C., Wendicke S., Görbig U., Balzarini J., Meier C. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003;2003:4786. [Google Scholar]

- Meier C., De Clercq E., Balzarini J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1998;1998:837. [Google Scholar]

- De Nanteuil M. V. G., Lila C., Bonnet J. and Fradin A., Eur. Pat. Appl., EP 599732 A1060119, 1994.

- Hercouet A., Le Corre M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;23:2145. [Google Scholar]

- Twyman L. J., Allsop D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:9383. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N., Miyata O., Naito T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:1491. [Google Scholar]

- Yáñez M., Fraiz N., Cano E., Orallo F. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;344:688. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland R. A., Evaluation of Enzyme Inhibitors in Drug Discovery, Wiley-Interscience, Hoboken, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach M., Riederer P., Youdim M. B. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;226:97. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(92)90170-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Peterson D. A., Kimura H., Schubert D. J. Neurochem. 1997;69:581. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69020581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger suite 2014-3, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, USA, 2014, Available at http://www.schrodinger.com/ (accessed Nov 2014).

- Binda C., Wang J., Pisani L., Caccia C., Carotti A., Salvati P., Edmondson D. E., Mattevi A. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:5848. doi: 10.1021/jm070677y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M. J., Janeiro P., González Franco R. M., Vilar S., Tatonetti N. P., Santana L., Uriarte E., Borges F., Fontenla J. A., Viña D. Future Med. Chem. 2014;6:371. doi: 10.4155/fmc.14.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delogu G. L., Serra S., Quezada E., Uriarte E., Vilar S., Tatonetti N. P., Viña D. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:1672. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M. J., Vilar S., García-Morales V., Tatonetti N. P., Uriarte E., Santana L., Viña D. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:1488. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinsky C. A., Lombardo F., Dominy B. W., Feeny P. J. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1997;23:3. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose A. K., Viswanadhan V. N., Wendoloski J. J. J. Comb. Chem. 1999;1:55. doi: 10.1021/cc9800071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonivento D., Milczek E. M., McDonald G. R., Binda C., Holt A., Edmondson D. E., Mattevi A. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:36849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu R., Constantinescu A. T., Reichmann H., Janetzky B. J. Neural Transm. 2007;S72:17. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-73574-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]