Abstract

Background

Approximately 50% of patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria (CIU/CSU) report hives and angioedema; some experience hives/angioedema only.

Objective

Assess omalizumab's effect on angioedema and quality of life (QoL) in subgroups with refractory CIU/CSU: those with and without angioedema.

Methods

Patients received omalizumab (75, 150 or 300 mg) or placebo every 4 weeks for 12/24 weeks. Angioedema and QoL were assessed [Urticaria Patient Daily Diary and Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI)]. Subgroups were based on the presence/absence of baseline angioedema 7 days prior to randomization.

Results

Patients with baseline angioedema randomized to omalizumab 300 mg had a greater reduction in mean weekly incidence of angioedema and mean number of days/week with angioedema vs. placebo at 12 and 24 weeks. A 3.3‐ to 4.5‐point greater mean reduction in DLQI score was achieved with omalizumab 300 mg treatment vs. placebo, above the minimal clinically important difference threshold. Results with lower doses vs. placebo were variable.

Conclusion

Compared with placebo, omalizumab 300 mg treatment over 12–24 weeks resulted in marked reduction in incidence and number of days/week with angioedema accompanied by clinically relevant improvement in QoL.

Introduction

Patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria (CIU/CSU) experience recurrent episodes of wheals (hives) and/or angioedema for at least 6 weeks.1, 2 Hives present as pruritic wheals of variable size with surrounding erythema.2 Individual hives are transient, typically resolving within 24 h of onset.2 Angioedema is characterized by rapidly occurring swellings of the lower dermis and subcutis, and often involves mucous membranes.2 The swellings may be erythematous or skin‐coloured, and sometimes painful, typically taking up to 72 h to resolve.2

Estimates of the proportion of patients with CIU/CSU experiencing both hives and angioedema, and those reporting either symptom in isolation vary: 33–67% of patients experience both symptoms; 29–65% experience hives only; and 1–13% experience angioedema only.3 In the latter group, hereditary angioedema due to C1‐inhibitor deficiency, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor‐mediated angioedema and other forms of bradykinin‐mediated angioedema need to be excluded before confirming a diagnosis of CIU/CSU.4

The signs and symptoms of CIU/CSU have a detrimental impact on patients’ health‐related quality of life (QoL).5, 6, 7 In addition, the presence of angioedema in patients with CIU/CSU is associated with a prolonged disease duration, with a greater proportion remaining symptomatic beyond 1 year compared with those experiencing hives only (64–70% vs. 43–48%, respectively).3, 8, 9

The current first‐line therapy for patients with CIU/CSU is non‐sedating second‐generation H1‐antihistamines.1 H1‐antihistamines provide complete symptomatic relief in <50% of all cases,3 so there remains an unmet need for a more targeted or optimal therapy in the majority of patients. Omalizumab, a humanized anti‐immunoglobulin E monoclonal antibody, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of adults and adolescents (≥12 years of age) with CIU/CSU who remain symptomatic despite H1‐antihistamine treatment.10 Approval of omalizumab in this indication was based on the efficacy and safety findings from three Phase III clinical studies [ASTERIA I (NCT01287117), ASTERIA II (NCT01292473) and GLACIAL (NCT01264939)].11, 12, 13 In these studies, omalizumab 300 and 150 mg was shown to significantly improve weekly itch severity score (ISS) and change from baseline in urticaria activity score over 7 days (UAS7) to Week 12 compared with placebo.11, 12, 13 Omalizumab 75 mg was also shown to significantly improve these efficacy variables in the ASTERIA I trial.11

Angioedema is more common in patients with CIU/CSU unresponsive to treatment with up to four times the approved dose of H1‐antihistamines compared with patients responsive to treatment (59% vs. 29%, respectively).14 In the Phase III studies, the efficacy of omalizumab on angioedema, specifically, the proportion of angioedema‐free days, and QoL, assessed using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), were investigated as secondary efficacy outcomes.11, 12, 13 Analyses of data from the subgroup of patients with CIU/CSU who had angioedema at baseline in these trials provide an opportunity to further investigate patient‐reported angioedema and QoL with omalizumab compared with placebo.

Objective

The objective of the current analysis of data from the Phase III studies was to investigate patient‐reported angioedema and QoL (DLQI scores) during treatment with omalizumab vs. placebo in those patients who had angioedema at baseline. All data refer to pooled analyses of ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL, unless specifically stated.

Methods

Patients and study design

ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL were multicentre, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled studies of omalizumab in patients with CIU/CSU who remained symptomatic despite treatment with approved doses of H1‐antihistamines (ASTERIA I/II) or H1‐antihistamines (up to four times the approved dose), H2‐receptor antagonists and/or leukotriene‐receptor antagonists (GLACIAL).11, 12, 13

The full methodology of these trials has been published previously.11, 12, 13 Briefly, in all three studies, patients were aged 12–75 years (18–75 years in Germany), with a diagnosis of CIU/CSU for ≥6 months; presence of itch and hives for ≥8 consecutive weeks (>6 consecutive weeks in GLACIAL) prior to enrolment despite treatment; an UAS7 ≥16 and a weekly ISS ≥8 for the 7 days before randomization; and an in‐clinic urticaria activity score (UAS) ≥4 on at least one of the screening visits (Day −14, −7 or 1).11, 12, 13 Patients were required to have received an approved dose of an H1‐antihistamine (ASTERIA I/II) or an H1‐antihistamine at up to four times the approved dose, and an H2‐receptor antagonist and/or leukotriene‐receptor antagonist (GLACIAL) for CIU/CSU for ≥3 consecutive days prior to Day −14 screening visit, and documented current use at the initial screening visit.11, 12, 13 Patients were excluded from the study if they presented with a disease with urticaria or angioedema symptoms (other than CIU/CSU), including hereditary or acquired angioedema.11, 12, 13

Eligible patients received subcutaneous omalizumab (75, 150 or 300 mg) or placebo every 4 weeks for 24 weeks in ASTERIA I and 12 weeks in ASTERIA II.11, 12 In GLACIAL, patients received subcutaneous omalizumab 300 mg or placebo every 4 weeks for 24 weeks.13

All three studies were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, US FDA regulations and any other national applicable laws. All patients (or their parents/legal guardian if under 18 years of age) provided informed written consent before participation.

Outcomes and statistical analysis

In all three studies, the presence of angioedema was assessed at baseline and throughout the study using the Urticaria Patient Daily Diary (UPDD; component: angioedema—‘yes’ or ‘no’). In the current retrospective analysis, patients were subdivided according to whether or not they experienced angioedema at baseline, defined as the presence of angioedema on at least 1 day during the 7 days prior to, but not including, the day of first treatment.

Baseline demographics and patient characteristics were summarized for the subgroup of patients with angioedema at baseline and the subgroup of patients without angioedema at baseline.

For the subgroup of patients with angioedema at baseline, the number of days per week with angioedema and the proportion of patients who were angioedema‐free each week were calculated from baseline to Week 12 (all three studies), and Week 24 [ASTERIA I and GLACIAL (pooled)], based on information entered in the UPDD. The proportion of angioedema‐free days was calculated from Week 4 to Week 12 for all three studies and from Week 4 to Week 24 for ASTERIA I and GLACIAL (pooled), and was analysed using a stratified Wilcoxon rank‐sum test, with baseline weight (<80 kg, ≥80 kg) as the stratification variable. Summary statistics included the mean (standard deviation; SD) number of days with angioedema with omalizumab or placebo, by week.

The change from baseline to Week 12 (weekly; all three studies) and Week 24 [weekly; ASTERIA I and GLACIAL (pooled)] in the overall DLQI score was also calculated for patients with and without angioedema at baseline. Change from baseline in overall DLQI score was analysed using an analysis of covariance (ancova) model with baseline overall DLQI score as a covariate and baseline weight (<80 kg vs. ≥80 kg) as strata. P‐values and 95% confidence intervals comparing the treatment difference in least squares means with omalizumab relative to placebo were derived from the ancova model.

Efficacy analyses were based on the modified intent‐to‐treat population (observed data), which included all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug, with no imputation for missing scores.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics and demographics

Overall, 460 of 975 patients (47.2%) in the pooled population experienced angioedema at baseline. The demographics of the subgroup with baseline angioedema were similar to the subgroup without baseline angioedema (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and demographics for ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL (pooled) for the subgroup of patients with baseline angioedema and the subgroup of patients without baseline angioedema (all patients who received at least one dose of study drug)

| Patients with baseline angioedema N = 460 | Patients without baseline angioedema N = 515 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 42.7 (13.6) | 41.9 (14.5) |

| Gender (female), n (%) | 331 (72.0) | 385 (74.8) |

| Race (White), n (%) | 389 (84.6) | 444 (86.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 29.7 (7.3) a | 29.6 (7.4) |

| Positive CU Index™ test, n (%) | 176 (38.4) a | 101 (19.7) b |

| Total IgE level, IU/mL, mean (SD) | 164.3 (294.8) c | 174.5 (320.8) d |

| Duration of CIU/CSU, years, mean (SD) | 7.5 (9.5) e | 6.5 (8.7) f |

| In‐clinic UAS, g mean (SD) | 5.4 (0.7) | 5.2 (0.8) |

| UAS7, h mean (SD) | 31.7 (6.5) | 30.2 (6.7) |

| Weekly ISS, h mean (SD) | 14.4 (3.6) | 13.8 (3.6) |

| Weekly no. of hives score, h mean (SD) | 17.3 (4.1) | 16.4 (4.4) |

| Weekly size of largest hive score, h mean (SD) | 15.9 (3.8) | 14.6 (4.3) |

| Weekly interference with sleep score, h mean (SD) | 12.5 (4.9) | 11.4 (4.9) |

| Weekly interference with daily activities score, h mean (SD) | 13.1 (4.5) | 12.5 (4.5) |

| Overall DLQI score, mean (SD) | 14.6 (6.7) i | 12.0 (6.1) j |

| MOS, mean (SD) | ||

| Optimal sleep | 0.4 (0.5) i | 0.4 (0.5) k |

| Short of breath | 21.1 (25.4) l | 18.0 (24.9) k |

| Sleep adequacy | 36.0 (23.3) m | 40.8 (24.2) j |

| Sleep disturbance | 51.1 (24.6) m | 49.4 (24.0) j |

| Sleep problems Index I | 47.9 (18.3) m | 44.5 (18.5) j |

| Sleep problems Index II | 49.8 (18.9) m | 47.0 (18.7) j |

| Sleep quantity | 6.3 (1.5) i | 6.4 (1.3) n |

| Snoring | 35.5 (32.1) o | 33.7 (33.0) k |

| Somnolence | 42.0 (22.5) m | 38.9 (22.0) j |

| CU‐Q2oL overall score | 48.6 (18.0) p | 39.3 (16.0) q |

| EuroQoL‐5D index score | 0.7 (0.3) m | 0.7 (0.2) r |

a n = 458; b n = 513; c n = 450; d n = 490; e n = 448; f n = 508; gDefined as largest value from Day −14 and Day −7 screening, and Day 1 visits; hBased on information collected in the UPDD; i n = 455; j n = 514; k n = 511; l n = 456; m n = 457; n n = 513; o n = 453; p n = 404; q n = 445; r n = 512.

Pooled data from the placebo and omalizumab arms.

BMI, body mass index; CIU/CSU, chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria; CU, chronic urticaria; CU‐Q2oL, Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EuroQoL‐5D, European Quality of Life‐5 Dimensions; IgE, immunoglobulin E; ISS, itch severity score; MOS, measures of sleep; SD, standard deviation; UAS, urticaria activity score; UAS7, urticaria activity score over 7 days; UPDD, Urticaria Patient Daily Diary.

Positive results on the Chronic Urticaria Index™ test, as assessed by in vitro basophil histamine assay, were seen more frequently in patients with baseline angioedema compared with those without angioedema (38.4% vs. 19.7%).

By contrast, baseline clinical disease activities, including the size and number of hives, itch intensity and interference with sleep and daily activities, disease duration and QoL impairment, were similar in patients with or without baseline angioedema (Table 1). There were no notable differences in previous CIU/CSU medications, which most commonly included steroids, H2‐receptor antagonists, leukotriene‐receptor antagonists and immunosuppressants (Table 2). Prior medical conditions occurred at similar frequencies in patients with or without angioedema and most commonly included a prior diagnosis of allergic rhinitis and asthma (Table 3).

Table 2.

Previous medications for CIU/CSU for ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL (pooled) for the subgroup of patients with baseline angioedema and the subgroup of patients without baseline angioedema (all patients who received at least one dose of study drug)

| Patients with baseline angioedema N = 460 | Patients without baseline angioedema N = 515 | |

|---|---|---|

| Any medication use | 460 (100.0) | 515 (100.0) |

| Number previous CIU/CSU medications, mean (SD) | 5.4 (2.9) | 4.7 (2.7) |

| Antihistamines, n (%) | 460 (100.0) | 514 (99.8) |

| H2‐receptor antagonist, n (%) | 242 (52.6) | 230 (44.7) |

| Steroids, n (%) | 220 (47.8) | 226 (43.9) |

| Leukotriene‐receptor antagonist, n (%) | 182 (39.6) | 154 (29.9) |

| Immunosuppressants, n (%) | 51 (11.1) | 36 (7.0) |

| Other, n (%) | 240 (52.2) | 248 (48.2) |

Pooled data from the placebo and omalizumab groups. Previous medications for CIU/CSU presented in descending order for patients with baseline angioedema. Multiple uses of a specific medication per patient were counted once in the frequency for the medication. Similarly, multiple uses within a specific medication class per patient were counted once in the frequency for the medication class. Includes concomitant medications started at any time before first treatment date.

CIU/CSU, chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria.

Table 3.

Commonly reported prior medical conditions, in addition to CIU/CSU, for ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL (pooled) for the subgroup of patients with baseline angioedema and the subgroup of patients without baseline angioedema (all patients who received at least one dose of study drug)

| Patients with baseline angioedema N = 460 | Patients without baseline angioedema N = 515 | |

|---|---|---|

| Allergic rhinitis, n (%) | 199 (43.3) | 229 (44.5) |

| Asthma, n (%) | 96 (20.9) | 135 (26.2) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 92 (20.0) | 112 (21.7) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia, n (%) | 64 (13.9) | 78 (15.1) |

Pooled data from the placebo and omalizumab groups. Prior medical conditions (ever reported) occurring in more than 10% of patients in any subgroup are included and are ordered by descending frequency for patients with baseline angioedema.

CIU/CSU, chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria.

Number of days per week with angioedema

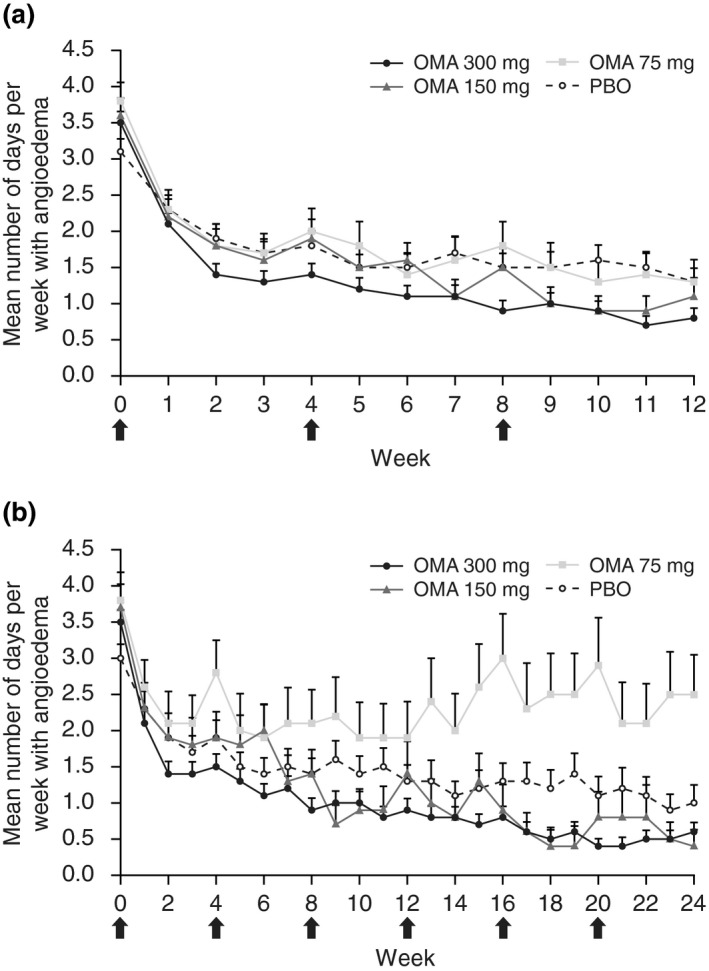

The mean number of days per week with angioedema was reduced with omalizumab and placebo by Week 12 (Fig. 1a). At baseline, patients in the omalizumab 300 mg group experienced angioedema for a mean (SD) of 3.5 (2.2) days, falling to 0.8 (1.8) days by Week 12. Corresponding values for the omalizumab 150 mg, omalizumab 75 mg and placebo groups were as follows: 3.6 (2.1) and 1.1 (1.9); 3.8 (2.1) and 1.3 (2.2); and 3.1 (1.9) and 1.3 (1.8) days, respectively.

Figure 1.

Number of days per week with angioedema in the baseline angioedema subgroup from baseline to (a) Week 12 in ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL (pooled) and (b) to Week 24 in ASTERIA I and GLACIAL (pooled).* *Modified intent‐to‐treat population (all patients with baseline angioedema). (a) PBO, n = 85–115; OMA 75 mg, n = 49–66; OMA 150 mg, n = 55–76; OMA 300 mg, n = 156–203. (b) PBO, n = 44–85; OMA 75 mg, n = 22–35; OMA 150 mg, n = 22–38; OMA 300 mg, n = 122–171. Arrows indicate monthly dosing. Note that dosing was every 4 weeks for 12 weeks in ASTERIA II. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. OMA, omalizumab; PBO, placebo.

A reduction in the mean number of days per week with angioedema (SD) was observed in the omalizumab 300 mg group at Week 24 [ASTERIA I and GLACIAL pooled; baseline, 3.5 (2.2); Week 24, 0.6 (1.5)] and placebo group [baseline, 3.0 (1.8); Week 24: 1.0 (1.8)]. Considering the omalizumab 150 and 75 mg groups (ASTERIA I only), the mean number of days per week with angioedema with omalizumab 150 mg at baseline was 3.7 (2.0) and at Week 24 was 0.4 (1.1), and with omalizumab 75 mg at baseline was 3.8 (2.3) and at Week 24 was 2.5 (2.8) (Fig. 1b).

Angioedema‐free patients each week

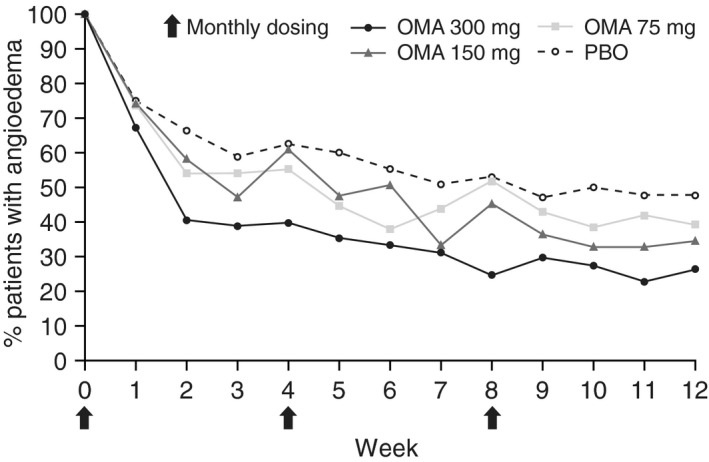

A consistent reduction in the number of patients with angioedema was observed in the omalizumab groups compared with placebo. The proportion of patients with angioedema was reduced from 100% at baseline in all groups to 26.3% in the omalizumab 300 mg group, 34.5% in the omalizumab 150 mg group, 39.2% in the omalizumab 75 mg group and 47.8% in the placebo group at Week 12 of the study (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients with baseline angioedema who had angioedema each week from baseline to Week 12 in ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL (pooled).* *Modified intent‐to‐treat population (all patients with baseline angioedema). PBO, n = 40–115; OMA 75 mg, n = 20–66; OMA 150 mg, n = 19–76; OMA 300 mg, n = 39–203. Arrows indicate monthly dosing. OMA, omalizumab; PBO, placebo.

Proportion of angioedema‐free days

During Weeks 4–12, the mean (SD) proportion of angioedema‐free days was higher in the omalizumab groups, significantly so with the 300 mg dose, than in the placebo group (Table 4). Results were similar for Weeks 4–24 in ASTERIA I and GLACIAL (pooled).

Table 4.

Proportion of angioedema‐free days from (A) Weeks 4 to 12 in ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL (pooled) and (B) Weeks 4 to 24 in ASTERIA I and GLACIAL (pooled) for patients with baseline angioedema

| Treatment | N a | n b | Angioedema‐free days, mean (%) (SE) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL (pooled)—Weeks 4–12 | ||||

| PBO | 115 | 94 | 78.6 (2.4) | |

| OMA 75 mg | 66 | 54 | 79.0 (4.1) | 0.1521 |

| OMA 150 mg | 76 | 64 | 80.7 (3.0) | 0.3154 |

| OMA 300 mg | 203 | 180 | 85.9 (1.8) | <0.0001 |

| ASTERIA I and GLACIAL (pooled)—Weeks 4–24 | ||||

| PBO | 85 | 66 | 81.4 (2.7) | |

| OMA 75 mg | 35 | 33 | 68.0 (6.4) | 0.3718 |

| OMA 150 mg | 38 | 34 | 80.0 (4.3) | 0.6121 |

| OMA 300 mg | 171 | 147 | 86.9 (1.9) | <0.0001 |

P‐values derived from stratified Wilcoxon rank‐sum test, with baseline weight (<80 kg, ≥80 kg) as the stratification variable.

Number of patients with baseline angioedema.

Number of patients with data between Weeks 4 and 12 or Weeks 4 and 24.

Modified intent‐to‐treat population (all patients with baseline angioedema).

OMA, omalizumab; PBO, placebo; SE, standard error.

QoL (DLQI) in patients with and without baseline angioedema

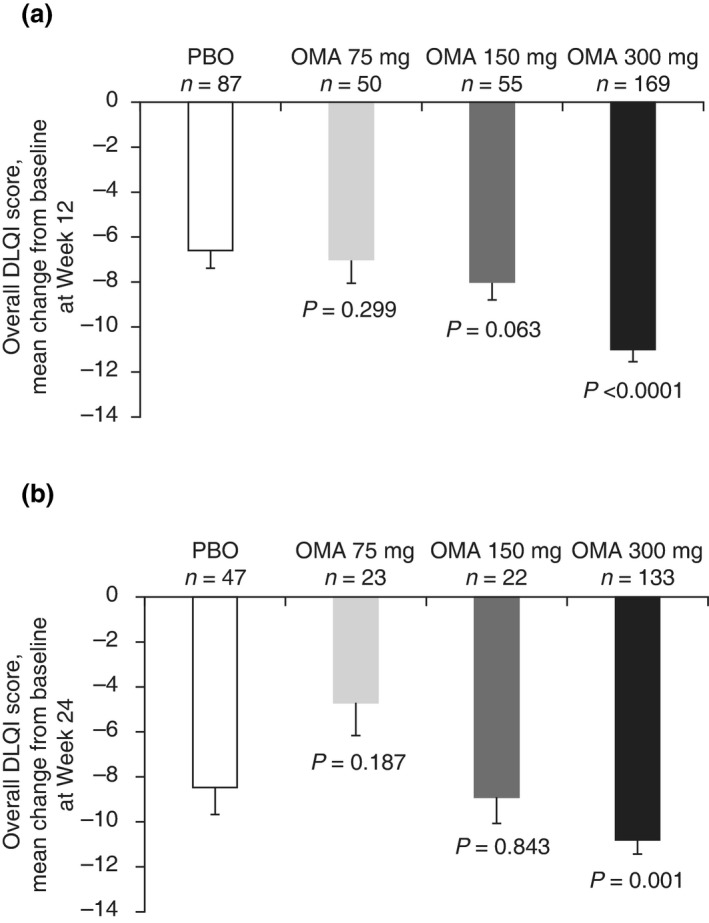

Omalizumab treatment with 300 mg, but not 150 or 75 mg, significantly improved DLQI scores in patients with and without baseline angioedema compared with placebo (Fig. 3, Table 5). Patients with and without baseline angioedema showed similar improvement on DLQI scores in response to omalizumab treatment (Fig. 3, Table 5).

Figure 3.

Change from baseline at (a) Week 12 in ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL (pooled) and (b) Week 24 in ASTERIA I and GLACIAL (pooled) on the overall DLQI score for patients with baseline angioedema.* *Modified intent‐to‐treat population (all patients with baseline angioedema). P‐value derived from ancova model. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; OMA, omalizumab; PBO, placebo.

Table 5.

LS mean differences in the change from baseline on the overall DLQI score with omalizumab vs. placebo (95% CI) at Week 12 in ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL (pooled) and Week 24 in ASTERIA I and GLACIAL (pooled) for patients with and without baseline angioedema

| Patients with angioedema at baseline | Patients without angioedema at baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N a | n b | Treatment difference in LS mean (95% CI) | P‐value | N a | n b | Treatment difference in LS mean (95% CI) | P‐value | |

| ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL (pooled)—12 weeks | ||||||||

| PBO | 115 | 87 | 127 | 108 | ||||

| OMA 75 mg | 66 | 50 | −1.15 (−3.33 to 1.03) | 0.2991 | 93 | 84 | −1.09 (−2.76 to 0.58) | 0.1982 |

| OMA 150 mg | 76 | 55 | −1.87 (−3.83 to 0.10) | 0.0627 | 86 | 78 | −2.47 (−4.19 to −0.75) | 0.0052 |

| OMA 300 mg | 203 | 169 | −4.49 (−5.92 to −3.06) | <0.0001 | 209 | 192 | −3.57 (−4.76 to −2.38) | <0.0001 |

| ASTERIA I and GLACIAL (pooled)—24 weeks | ||||||||

| PBO | 85 | 47 | 78 | 60 | ||||

| OMA 75 mg | 35 | 23 | 2.41 (−1.20 to 6.03) | 0.1868 | 42 | 36 | −1.78 (−3.89 to 0.32) | 0.0962 |

| OMA 150 mg | 38 | 22 | −0.35 (−3.83 to 3.13) | 0.8427 | 42 | 33 | −1.32 (−3.36 to 0.71) | 0.1999 |

| OMA 300 mg | 171 | 133 | −3.32 (−5.27 to −1.36) | 0.001 | 162 | 136 | −2.64 (−3.98 to −1.29) | 0.0001 |

Number of patients with or without baseline angioedema.

Number of patients with data at Week 12 or Week 24.

CI, confidence interval; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; LS, least squares; OMA, omalizumab; PBO, placebo. Modified intent‐to‐treat population (all patients with baseline angioedema). The LS mean was estimated using ancova model with baseline overall DLQI score as covariate, and baseline weight (<80 kg vs. ≥80 kg) as strata. P‐value derived from ancova model.

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of pooled data from the pivotal clinical studies ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL for patients with angioedema at baseline, patient‐reported angioedema was reduced and QoL significantly improved with omalizumab vs. placebo, after 12 (all three studies) and 24 weeks (ASTERIA I and GLACIAL pooled) of treatment. The greatest clinical benefit in patients with baseline angioedema was observed in the omalizumab 300 and 150 mg groups. By contrast, omalizumab 75 mg did not generally improve outcomes over placebo.

In all groups, patients had angioedema at baseline for about 3.5 days per week; after receiving monthly doses of omalizumab 300 and 150 mg for 12 weeks, this had declined to 0.8 and 1.1 days per week, respectively, and was further reduced to 0.6 and 0.4 days per week, respectively, by 24 weeks of treatment in the pooled ASTERIA I and GLACIAL analysis. The reduction in angioedema to around 0.5 days per week with omalizumab 150–300 mg exceeded that observed with placebo, where patients had angioedema for 1.3 and 1.0 days per week at Week 12 and Week 24, respectively, of the pooled analyses.

In the subgroup of patients with baseline angioedema, the proportion of patients who continued to report angioedema declined in the placebo group throughout the study, and accounted for only 47.8% of patients at Week 12. The self‐resolution and reduced recurrence of angioedema in a proportion of patients receiving placebo highlight the transient nature of angioedema episodes; however, a greater reduction in angioedema episodes was observed with omalizumab compared with placebo, with fewer patients reporting an angioedema episode each week with omalizumab 300 mg throughout the 12‐week pooled analysis. By Week 12, omalizumab 300 mg had reduced the proportion of patients with angioedema to 26.3%.

Omalizumab 300 mg was the only dosing regimen that was more efficacious than placebo in improving the QoL for patients with baseline angioedema. In the pooled analyses, a 3.3‐ to 4.5‐point greater reduction in DLQI score was achieved with 12–24 weeks of omalizumab 300 mg treatment vs. placebo. The difference in change in DLQI score between the omalizumab 300 mg and placebo groups was above the previously defined minimal clinically important difference threshold of 2.2–3.1 points, indicating a clinically meaningful benefit with omalizumab treatment;15 improvement in DLQI with omalizumab 300 mg was similar for patients without angioedema at baseline (2.6–3.6 points above that achieved with placebo). The observation that the benefits of omalizumab on QoL were similar in both subgroups of patients is perhaps not surprising if we consider that it is likely the emotional aspect, i.e. fear/anxiety of a subsequent angioedema attack that has most impact on patient QoL. This emotional impact on QoL has been highlighted by results from studies utilizing the Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire, the first specific patient‐reported outcome assessment of QoL in patients with recurrent angioedema, and in an European study assessing the real‐world experience of patients with hereditary angioedema.16, 17, 18 Therefore, it would be of interest in future CIU/CSU subgroup analyses to investigate patients who have experienced angioedema vs. those who have never experienced angioedema. In addition, studies on the minority of patients with CIU/CSU who have angioedema in isolation (i.e. in the absence of hives) are warranted.

It is reassuring that the findings from this post hoc pooled analysis are consistent with the greater efficacy and improvement in QoL observed with omalizumab 300 mg compared with placebo observed during the individual trials.11, 12, 13, 19 Caution is warranted in the interpretation of the results from the ASTERIA I and GLACIAL pooled analysis for the omalizumab 75 and 150 mg groups as these dosing regimens were not included in the GLACIAL study.13 Indeed, the highly fluctuating burden of angioedema (measured as days per week with angioedema) observed with omalizumab 75 mg in the 24‐week ASTERIA I and GLACIAL pooled data are a notable exception to the overall observed benefit of omalizumab treatment in these post hoc analyses, and may be a result of the small sample size in the omalizumab 75 mg data set.

Additional limitations of this study include the unavoidable subjectivity of patient‐reported outcomes. Patients were assessed for the presence or absence of angioedema during a baseline period defined as the 7 days prior to randomization. However, the transitory nature of angioedema episodes means that some patients could have been misclassified as angioedema‐free and later gone on to experience angioedema; likewise, patients with angioedema during the baseline period could have been experiencing a single, self‐resolving episode without recurrence during the study period. Furthermore, facial wheals can be difficult to distinguish from angioedema, which may potentially increase the incidence of reported angioedema during the baseline assessment and therefore suggest a greater response with omalizumab than that actually achieved. Future studies of omalizumab on angioedema should try to account for this through measurements of the site, size, severity and duration of wheals.

Omalizumab represents an important add‐on treatment option for the approximately 50% of CIU/CSU cases that remain symptomatic on H1‐antihistamine therapy.3 The observation that angioedema is more common in these patients compared with patients responsive to treatment highlights the importance of angioedema as a clinical marker of symptom burden in CIU/CSU.14 The steady and consistently greater decline in incidence and number of days per week with angioedema with omalizumab 300 mg compared with placebo in these 12‐ and 24‐week pooled analyses, accompanied by a clinically relevant improvement in QoL, is strongly supportive of the benefit of omalizumab 300 mg in the treatment of recalcitrant CIU/CSU.

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this work to our esteemed colleague Dr Sheldon Spector (13 February 1939 to 29 December 2015).

Conflict of Interest and funding information

Marcus Maurer has received research funding and/or honoraria for lectures and/or consulting from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Novartis Pharma AG, and Genentech, Inc. Jonathan Bernstein has served as principal investigator, consultant and speaker for Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation and Genentech, Inc. Howard Sofen has received honoraria for serving as a consultant, speaker and investigator for Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation and Genentech, Inc. Benjamin Ortiz and Farid Kianifard are employees and stockholders of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Susan Gabriel was an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation at the time of this work. She is no longer employed at Novartis, but is still a Novartis stockholder.The ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II and GLACIAL studies were funded by Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA, and Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland.Some of the results within this manuscript relating to ASTERIA I and II were previously presented at the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Annual Meeting, 20–24 March 2015, San Francisco, CA, USA. Medical writing and editorial support in the development of this manuscript were provided by Katy Tucker, PhD, and Christina Mackins‐Crabtree, PhD, of Fishawack Communications, Oxford, UK, and statistical/programming support was provided by PPD Inc., NC, USA. This service was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA and Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA.

The copyright line for this article was changed on 27 July 2018 after original online publication.

References

- 1. Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA et al The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 133: 1270–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R et al The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy 2014; 69: 868–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev‐Jensen C et al Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA(2)LEN task force report. Allergy 2011; 66: 317–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cicardi M, Aberer W, Banerji A et al Classification, diagnosis, and approach to treatment for angioedema: consensus report from the Hereditary Angioedema International Working Group. Allergy 2014; 69: 602–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grob JJ, Gaudy‐Marqueste C. Urticaria and quality of life. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2006; 30: 47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Donnell BF. Urticaria: impact on quality of life and economic cost. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2014; 34: 89–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turner S, Vietri J, Tian H, Isherwood G, Balp M‐M. The burden of chronic hives from the US patients’ perspective. Poster presented at: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy 26th Annual Meeting and Expo; April 1–4, 2014; Tampa, FL, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Champion RH, Roberts SO, Carpenter RG, Roger JH. Urticaria and angio‐oedema. A review of 554 patients. Br J Dermatol 1969; 81: 588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Toubi E, Kessel A, Avshovich N et al Clinical and laboratory parameters in predicting chronic urticaria duration: a prospective study of 139 patients. Allergy 2004; 59: 869–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xolair® (omalizumab) US prescribing information. [WWW document] 2014. URL http://www.gene.com/download/pdf/xolair_prescribing.pdf (last accessed: 26 September 2016).

- 11. Saini SS, Bindslev‐Jensen C, Maurer M et al Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria who remain symptomatic on H1‐antihistamines: a randomized, placebo‐controlled study. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135: 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maurer M, Rosen K, Hsieh HJ et al Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 924–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaplan A, Ledford D, Ashby M et al Omalizumab in patients with symptomatic chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria despite standard combination therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132: 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Magen E, Mishal J, Zeldin Y, Schlesinger M. Clinical and laboratory features of antihistamine‐resistant chronic idiopathic urticaria. Allergy Asthma Proc 2011; 32: 460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shikiar R, Harding G, Leahy M, Lennox RD. Minimal important difference (MID) of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): results from patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005; 3: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M et al Development and construct validation of the angioedema quality of life questionnaire. Allergy 2012; 67: 1289–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weller K, Magerl M, Peveling‐Oberhag A, Martus P, Staubach P, Maurer M. The Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE‐QoL) – assessment of sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy 2016; 71: 1203–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bygum A, Aygoren‐Pursun E, Beusterien K et al Burden of illness in hereditary angioedema: a conceptual model. Acta Derm Venereol 2015; 95: 706–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zazzali JL, Kaplan A, Maurer M et al Angioedema in the omalizumab chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria pivotal studies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2016; 117: 370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]