Abstract

Bisphenol A (BPA) is commonly manufactured to make polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins for use in consumer products and packaged goods. BPA has been found in several different types of environmental media (e.g., food, dust, and air). Many cross-sectional studies have frequently detected BPA concentrations in adult urine samples. However, limited data are available on the temporal variability and important predictors of urinary BPA concentrations in adults. In this work, the major objectives were to: 1) quantify BPA levels in duplicate-diet solid food, drinking water, hard floor surface wipe, and urine samples (first-morning void [FMV], bedtime, and 24-h) collected from adults over a six-week monitoring period; 2) determine the temporal variability of urinary BPA levels using concentration, specific gravity (SG) adjusted, creatinine (CR) adjusted, and excretion rate values, and; 3) examine associations between available study factors and urinary BPA concentrations. In 2009–2011, a convenience sample of 50 adults was recruited from residential settings in North Carolina. The participants completed diaries and collected samples during weeks 1, 2, and/or 6 of a six-week monitoring period. BPA was detected in 38%, 4%, and 99% of the solid food (n = 775), drinking water (n = 50), and surface wipe samples (n = 138), respectively. Total BPA (free plus conjugated) was detected in 98% of the 2477 urine samples. Median urinary BPA levels were 2.07 ng/mL, 2.20 ng/mL-SG, 2.29 ng/mg, and 2.31 ng/min for concentration, SG-adjusted, CR-adjusted, and excretion rate values, respectively. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) estimates for BPA showed poor reproducibility (≤0.35) for all urine sample types and methods over a day, week, and six weeks. CR-adjusted bedtime voids collected over six-weeks required the fewest, realistic number of samples (n = 11) to obtain a reliable biomarker estimate (ICC = 0.80). Results of linear mixed-effects models showed that sex, race, season, and CR-level were all significant predictors (p < 0.05) of the adults’ urinary BPA concentrations. BPA levels in the solid food and surface wipe samples did not contribute significantly to the participants’ urinary BPA concentrations. However, a significant positive relationship was observed between solid food intake and urine-based estimates of BPA dose, when aggregated over 24-h periods. Ingestion of BPA via solid food explained only about 20% of the total dose (at the median of the dose distribution), suggesting that these adults were likely exposed to other major unknown (non-dietary) sources of BPA in their everyday environments.

Keywords: Bisphenol A (BPA), Adults, Urine, Homes, Biomonitoring, Temporal, Determinants

1. Introduction

Bisphenol A (4,4′-dihydroxy-2,2-diphenylpropane, [BPA]), is a synthetic chemical with over two billion pounds produced annually in the United States (US) (Geens et al., 2012; Loganathan and Kannan, 2011). BPA is commonly used to create polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins for use in everyday consumer products and packaged goods (ACC, 2015). Several studies have found measurable levels of BPA in many commonly used consumer items including food storage containers, food cans (liners), tableware, paper receipts, electronic equipment, magazines, paints, adhesives, shampoos, bar soaps, body lotions, sunscreens, nail polishes, and recycled paper towels, napkins and toilet papers (Dotson et al., 2012; Geens et al., 2012; Liao and Kannan, 2011; Vandenberg et al., 2007).

Due to its widespread use, BPA has been found in several different types of environmental media including foods, beverages, dust, surface wipes, and air at residences in the US (Loganathan and Kannan, 2011; Rudel et al., 2003; Schecter et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2007). Although adults can be exposed to BPA though multiple routes, research has indicated that dietary ingestion is likely the dominant exposure route (> 90%) (Geens et al., 2012; Morgan et al., 2011; Von Goetz et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2015). Currently, the US Food and Drug Administration does not regulate the amount of BPA that can be present in foods or beverages for adult consumption (Schecter et al., 2010). Several recent studies have raised concerns that exposures to BPA at environmental concentrations may be adversely impacting human health (i.e., reproductive, developmental, and cardiovascular effects) (Rezg et al., 2014; Rochester, 2013; Schug and Birnbaum, 2014).

Once ingested, BPA undergoes rapid metabolism in the liver and is mainly excreted in the urine as conjugated BPA-glucuronide with an elimination half-life of < 7 h in adults (Dekant and Volkel, 2008; Thayer et al., 2015; Volkel et al., 2002). In recent cross-sectional studies (2009–2014), total BPA was frequently detected (> 73%) in the urine samples of adults recruited from the US general population (CDC, 2017; Cox et al., 2016; LaKind and Naiman, 2015; Ye et al., 2015). In these studies, median urinary BPA concentrations ranged from 0.36–2.4 ng/mL.

A number of US studies have examined the short- or long-term variability (1 week to 3 years) of total BPA concentrations in spot, first-morning void (FMV), and/or 24-h urine samples in adults in non-occupational settings (Braun et al., 2011, 2012; Cox et al., 2016; Meeker et al., 2013; Philippat et al., 2013; Pollack et al., 2016; Reeves et al., 2014; Townsend et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2011). In some of these studies, FMVs has been the preferred sample type collected based on the assumption that they provide the best weighted-average biomarker level over a day (Kissel et al., 2005). None of these prior studies have specifically examined the levels of BPA in bedtime voids. Across these various studies, poor reproducibility (ICC < 0.30) of repeated measurements of BPA occurred in adult urine samples regardless of urine sample type and method of adjustment (unadjusted, specific gravity [SG] adjusted, or creatinine [CR] adjusted). The observed high within-individual variability reported in these studies suggests that a single BPA urine measurement is probably not sufficient to characterize a person’s average exposure over a day or longer. However, information is currently lacking on the actual type and number of urine samples that are likely needed to obtain a reliable BPA biomarker estimate for adults over a day or longer.

Several US studies of non-occupationally exposed adults have reported significant (p < 0.05) associations occurring between urinary BPA concentrations and various sociodemographic, lifestyle, and dietary factors including age, gender, and race/ethnicity (LaKind and Naiman, 2008, 2015), pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) (Meeker et al., 2013), contact with paper receipts (Gerona et al., 2016), and consumption frequency of canned vegetables (Braun et al., 2011), hamburgers (Quiros-Alcala et al., 2013), and soda (LaKind and Naiman, 2008; Quiros-Alcala et al., 2013). Currently, we are not aware of any published study that has quantitatively examined the association between measured BPA levels in the actual consumed diets of adults and their urinary BPA levels.

In previous work from the Pilot Study to Estimate Human Exposures to Pyrethroids using an Exposure Reconstruction Approach (Ex-R study), we quantified the levels of several pyrethroid insecticides and pyrethroid degradates in media (duplicate-diet solid food, drinking water, hard floor surface wipes, and urine) for 50 adults in residential settings over a six-week monitoring period in North Carolina (NC) in 2009–2011 (Clifton et al., 2015; Morgan et al., 2016a; Morgan et al., 2016b; Starr et al., 2017). In this present work, we have now quantified the concentrations of BPA in the same media (above) from the Ex-R study. The major objectives were to: 1) quantify the BPA levels in the duplicate-diet solid food, drinking water, hard floor surface wipe, and urine samples (spot and 24-h) collected from 50 Ex-R adults over a six-week monitoring period; 2) determine the temporal variability of BPA levels in the FMV, bedtime, and 24-h urine samples as concentration, SG-adjusted, CR-adjusted, and excretion rate values, and; 3) examine associations between available study factors and urinary levels of BPA.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study cohort

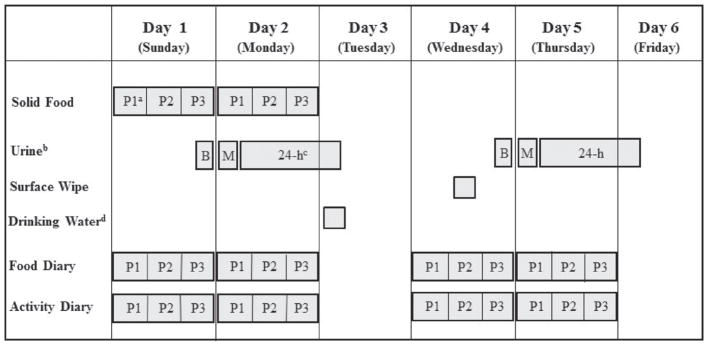

The Ex-R study design and sampling methodology has been described earlier in Morgan et al., 2016a. This study was designed to assess the short-term (over six-weeks) exposures of adults to pyrethroid insecticides and BPA in selected media at residences. Briefly, this observational exposure measurements study was conducted at the US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Human Studies Facility (HSF) in Chapel Hill, NC, and within a 40-mile radius of the HSF at the adult participants’ homes. A total of 50 adults between the ages of 19 and 50 years old were recruited into the study. The participants filled out diaries (food and activity) and collected duplicate-diet solid food, drinking water, hard floor surface wipe, and urine samples (spot and 24-h) during weeks 1, 2, and 6 of a six-week monitoring period from November 2009 to May 2011 (Fig. 1). Each sampling week started on Sunday (day 1) and ended on Friday (day 6). The University of North Carolina’s Institutional Review Board approved the Ex-R study protocol and procedures (study number 09–0741) in 2008. All study adults reviewed and signed informed consent forms before participating.

Fig. 1.

Sampling schedule for the Ex-R study field activities for each sampling week (1, 2, or 6).e

2.2. Collection of diaries and physical information

The Ex-R participants filled out the food and activity diaries during sampling weeks 1, 2, and 6 of the six-week monitoring period (Morgan et al., 2016a). Food diaries were complete on days 1–2 and days 4–5 of each sampling week. Each 24-h sampling day consisted of three consecutive time periods (period 1 = 4:00–11:00 am, period 2 = 11:00 am–5:00 pm, and period 3 = 5:00 pm–4:00 am). The food diary was used to record all of the solid and liquid foods (including estimated amounts) consumed by individual participants during each sampling time period. Activity diaries were completed on days 1–2 and days 4–5 of each sampling week. Each 24-h sampling day in this diary consisted of three consecutive time periods (as described above). The activity diary was used to record the participants’ activity levels (sleeping, low [e.g., sitting/standing], medium [e.g., walking], or high [e.g., running]) in consecutive, 30-min time increments during each sampling time period. In addition, an EPA technician recorded specific physical information (weight, height, age, and sex) about each participant at the HSF at the beginning of sampling week 1.

2.3. Collection of samples

The participants were trained to collect their own duplicate-diet solid food, drinking water, hard floor surface wipe, and urine samples during weeks 1, 2, and/or 6 of a six-week monitoring period (Morgan et al., 2016a). Duplicate-diet liquid food samples (mainly beverages, excluding drinking water) were not collected in the Ex-R study because of participant burden and budget constraints. The adults collected duplicate amounts of all solid food samples (e.g., fruits, vegetables, meats, pastas, soups, crackers, cheeses, breads, cookies, and ice creams) they consumed on sampling days 1 and 2 during each sampling week. The solid food samples were collected over three consecutive time periods (1, 2, or 3) each sampling day (as mentioned above in Section 2.2). For each period, the participants placed their solid food items into a (BPA-free) re-sealable polyethylene bag (31 × 31 cm, Uline Shipping Supply Specialist). A drinking water sample was obtained from the participants’ main source of water (i.e., municipal or well) on day 3 of the last sampling week, only. Drinking water samples (> 500 mL) were placed directly into a (BPA-free) 1 L polypropylene container (Government Scientific Source). Hard floor surface wipe samples (pre-cleaned 100% cotton pad wetted with 10 mL of isopropanol) were collected from two, separate high traffic areas (929 cm2 each) of the participants’ kitchens (e.g., sink, stove, or entryway) on day 4 of each sampling week. After sampling was completed, each cotton pad was put into a separate pre-cleaned (60 mL) amber glass jar (Government Scientific Source). Lastly, the participants collected several different types of urine samples (FMV, bedtime, and 24-h). Bedtime voids were collected before the participants went to sleep on day 1 and day 4 of each sampling week. FMV’s were collected after the participants woke up on day 2 and day 5 of each sampling week. For the 24-h samples, the participants collected up to 11 consecutive, urine voids beginning after the FMV on day 2 or day 5 until the collection of the FMV the next morning (day 3 or day 6). Each urine sample was collected directly into a 1 L polypropylene container. All collected samples were immediately stored by the participants in provided portable thermoelectric coolers (Vinotemp or Princess International®).

The participants returned the coolers containing the study samples to the HSF between 8:00–11:00 am on days 3 or 6 of each sampling week. At the HSF, the mass (g) of each food sample was measured using an electronic weight scale. The samples were then transported in the portable coolers at reduced temperatures to the EPA laboratory in Research Triangle Park, NC.

At the laboratory, an EPA technician made up to eight aliquots (8 mL each) from each urine void; the individual urine aliquots were stored in 10 mL (BPA-free) cryovials (Simport polypropylene T310-10A). The urine samples, solid food, and surface wipes were all stored in laboratory freezers (≤−20 °C) until analysis. The drinking water samples were placed into a refrigerator (~4 °C) until chemical extraction (within 1–2 days).

2.4. Sample analysis

The separate analytical methods used to quantify BPA levels in the solid food, drinking water, surface wipe, and urine samples are described below. All chemical analyses of the sampled media were performed at the EPA laboratory in Research Triangle Park, NC, except for the urine samples (Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health environmental laboratory in Atlanta, Georgia). The quality assurance and quality control procedures, including results, for each medium are provided in Appendix A.

2.4.1. Duplicate-diet solid food

Each solid food sample (n = 775) was prepared using a modified QuEChERS (quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe) method (Anastassiades et al., 2003; Clifton et al., 2015). Briefly, the samples were homogenized and 2 g amounts placed into 50 mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes. An internal standard solution and a ceramic homogenizer were added to each tube prior to vortex extraction with acetonitrile in combination with magnesium sulfate and sodium acetate extraction salt. The tubes were centrifuged at 4000 RPM for 5 min, and the acetonitrile extract was transferred to a 15-mL polypropylene tube containing graphitized carbon black. The tubes were vortexed to facilitate dispersive solid phase extraction and then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. The extract was transferred to a 50-mL tapered glass centrifuge tube and evaporated just to dryness using a parallel evaporator. The extracts were reconstituted with 1 mL of acetonitrile and transferred to autosampler vials. Next, the extracts were silylated by adding 100 μL of Sylon BFT and mixed and heated at 80 °C for 15 min. After cooling, the extracts (1 mL) were mixed again, and BPA concentrations were determined using an Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph-mass selective detector (GC-MSD) equipped with an autosampler. Separation was achieved using a Varian VF-XMS column (20 m × 0.15 mm × 0.15 μm), with helium as the carrier gas. The initial temperature was 75 °C for 2 min., raised to 217 °C at 10 °C/min. and then to 223 °C at 1 °C/min., and the final temperature of 330 °C was held for 5 min. The ions monitored for BPA were m/z 357 (quantifier) and m/z 372 (qualifier). The internal standard used for BPA was BPA 13C12 with ions m/z 369 and 384 monitored. The estimated limit of quantitation (LOQ) was 1.1 ng/g for BPA in solid food.

2.4.2. Drinking water

Drinking water samples (n = 50) in 1 L polypropylene containers were removed from the refrigerator (within 1–2 days) and warmed to room temperature. The water volume was measured, and the surrogate recovery standard (fipronil des F3) added. After adjustment of the pH to pH = 3, sufficient methanol was added so that the ratio of water: methanol was 10:1 (v:v). BPA was extracted from the water/methanol mixture using a 500 mg C18 cartridge that was in-line with an active pump system. The samples were stirred continuously during this process to minimize adherence of BPA to the surface of the containers. After each sample was extracted, BPA was collected by flushing the system (pump lines, SPE cartridge, and polypropylene sample container) with methanol, followed by ethyl acetate, and then hexane. All solvents were combined, and the volume was reduced to approximately 100 μL by evaporation. To this, 3 mL of pH 3 water and 3 mL hexane:toluene 1:1 (v:v) were added. The extracts were partitioned, and the organic layer was collected. The extracts were partitioned two additional times, and each time fresh organic solvents were added, collected, and combined. The internal standard, (13C12 Bisphenol A) and 200 μL of pH 3 water were added, and the volume was reduced under nitrogen to 200 μL. Finally, 800 μL of methanol was added to the extracts, and the contents were transferred to autosampler vials. All extracts were stored in a freezer (−20 °C) until analysis. BPA concentrations were determined using a high-performance liquid chromatograph coupled to a tandem mass spectrometer (LC-MS/MS). The mobile phase was 5 mM ammonium acetate:methanol, (2:8) at a flow rate of 400 μL/min, and the analytical column was C18 (3.0 × 150, 3.5 μm). The ions used for BPA were m/z 227 (Q1) and m/z 212 (Q3). The internal standard used for BPA was BPA 13C12 using ions at m/z 239 (Q1) and 224 (Q3). The estimated LOQ for BPA was 0.032 ng/mL in drinking water.

2.4.3. Hard floor surface wipe

The method for the extraction and analysis of the surface wipes has been described in Starr et al., 2017. Briefly, for each participant, the two collected surface wipes (from two different areas of the kitchen) were combined into one sample per sampling week. BPA was extracted from the paired wipe samples (n = 138) using pressurized liquid extraction with hexane:acetone, 25:75 (v/v). The samples were cleaned using a C18 cartridge, and the volume reduced to 200 μL under nitrogen. The internal standard, (13C12 Bisphenol A), was added, followed by an additional amount of methanol and water such that the final volume was 1 mL with a ratio of aqueous:organic of 6:4. The samples were vortexed (~5 s.), transferred to autosampler vials and stored at −20° C until analysis. The extracts were analyzed by LC-MS/MS using the same settings, solvents, flow rate and column that was used for the analysis of BPA in drinking water described above. The ions used for BPA were m/z 227 (Q1) and m/z 212 (Q3). The internal standard used for BPA was BPA 13C12 using ions at m/z 239 (Q1) and 224 (Q3). The estimated LOQ for BPA was 0.027 ng/cm2 in the surface wipes.

2.4.4. Urine

One set of the participants’ urine aliquots was shipped (8 mL each) in coolers with dry ice overnight to Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia (Morgan et al., 2016a). The urine aliquots were kept in laboratory freezers at ≤−20 °C until chemical analysis. For the 24-h urine samples, each urine void (aliquot) was analyzed separately. The urine aliquot was thawed overnight, then 1 mL was placed into a vial, and a labeled standard (13C12 bisphenol A) was added. The sample was hydrolyzed with a β-glucuronidase/sulfatase (Helix pomatia) mixture in 0.1 M acetate buffer for about 16-h at 37 °C. To each sample, 250 μL of a 1 M ammonium acetate and 1 mL of 33% formic acid. Next, the sample was subjected to solid phase extraction (3 cm3/60 mg OASIS HLB cartridge), and eluted with 1.5 mL methanol (twice), then evaporated to dryness under nitrogen. The dried extract was reconstituted with 1 mL of dichloromethane. Then 0.5 mL of a 0.1 M tetra-butylammonium hydrogen sulfate, 0.05 mL of a 0.2 M sodium hydroxide, and 20 μL of pentafluorobenzyl bromide were added to the vial, and the mixture was vortexed (~ 5 s.). Next, the extract was incubated to form the pentafluorobenzyl ether of BPA, centrifuged, and the dichloromethane (bottom) layer was transferred to another vial, and evaporated to dryness. Finally, the extract was reconstituted with 50 μL of isooctane and transferred to a GC vial. The 2501 urine extracts (1 μL) were quantified for total BPA levels (free plus conjugated) using an Agilent 5977 series GC-MSD using negative chemical ionization (methane as the reagent gas) with a single quadrupole mass spectrometer (MS), equipped with an autosampler. Chromatographic separation was performed with a DB-5 capillary column (J&W Scientific, 30 m, 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 μ film thickness), and the carrier gas was helium. The temperature was initially set at 60 °C, raised to 200 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min, and then to 280 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. The MS was run in the selected ion-monitoring mode, and the masses selected were m/z 407 for BPA and m/z 419 for its labeled standard. As an adequate confirmation ion was unavailable, we used tight limits (± 1%) on the relative retention time (BPA/labeled standard) for positive identification of BPA. The estimated LOQ was 0.10 ng/mL for BPA in urine. Quality control and assurance procedures were incorporated into the analyses. Two positive and two negative (blanks) samples were analyzed concurrently with unknown samples and calibrants for each run. Special care was take to avoid BPA contamination of reagents (e.g., use of BPA free water for reagents). NIST SRMs 3672 (smoker urine) and 3673 (nonsmoker urine) were analyzed periodically alongside samples. In general, one of each SRM was analyzed per 100 samples. Our quantified levels of BPA in SRMs 3672 (N = 36) and 3673 (N = 36) were 3.09 ± 0.17 and 1.94 ± 0.18 which were within the NIST tolerance ranges.

CR- and SG-levels were quantified in an identical set of the participants’ urine aliquots (8 mL each) at the EPA laboratory (Morgan et al., 2016a). Individual urine aliquots were thawed overnight in a refrigerator (~4 °C). CR-levels were analyzed in each urine aliquot using a modified Jaffé method (Andersen et al., 2014). SG-levels were measured in the urine aliquots using a hand-held refractometer (Atago® model no. 3741) (Andersen et al., 2014).

2.5. Data and statistical analysis

For each type of matrix, sample data values below the LOQ for BPA were replaced with the value of (Verbovsek, 2011). Descriptive statistics were computed for BPA levels in the solid food, drinking water, and surface wipe samples. Descriptive statistics were also calculated for BPA by urine sample type (FMV, bedtime, 24-h and total) as concentration (ng/mL), SG-adjusted (ng/mL-SG), CR-adjusted (ng/mg), and excretion rate (ng/min) values. The volume of each urine void ranged from 5 mL to 1000 mL (an upper bound based on the size of the urine collection containers). The participants had an average of eight urine voids per sampling day (range = 3 to 11 [an upper bound based on the maximum number of provided collection containers]).

All data values were log-transformed (ln) prior to statistical analysis. Using a one-way random effects model, we estimated the within-and between-person variance components for BPA concentrations by each urine sample type and method (adjusted and unadjusted) over a day, week, and six-weeks. These variance component estimates were then used to calculate ICCs and 95% between and within-person fold-ranges (bR0.95 and wR0.95) for each urine sample type and method over each specified period of time (Morgan et al., 2016a; Rappaport and Kupper, 2008). The ICC is defined as the ratio of the between-person variance to the total variance; ICCs values can range from 0 (low reliability) to 1 (high reliability). In exposure and epidemiology studies, ICC’s are commonly used to signify either poor reproducibility (< 0.40), good reproducibility (0.40–0.75), or excellent reproducibility (> 0.75) of a spot urinary biomarker measurement (Fleiss, 1985; Rosner, 2006). Next, we calculated the number of random spot urine samples per participant that would likely be needed to obtain a reliable BPA concentration estimate (ICC = 0.80) by urine sample type and method for each time period using the following equation by Fleiss (1985):

| (1) |

where m is the estimated number of random spot BPA urine measurements per participant needed to accurately rank participants in this study cohort, ρr, m is the specified reliability of the mean (0.80), and ρr is the ICC value by urine sample type and method for each specified time period.

Prior to building linear mixed effects models, multicollinearity between predictors (BMI, age and the ln of urinary CR-concentration) were measured using variance inflation factor (VIF). Our VIF values were < 1.3 which indicated there was not significant collinearity (Neter et al., 1996; Griffth and Amerhein, 1997).

SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC, USA) was used for all linear mixed effects modeling (Proc Mixed, SAS®). We first developed a “urine” model to determine the effects of available (non-environmental matrix) predictors on urinary BPA concentrations (Morgan et al., 2016a). The 50 Ex-R participants were treated in the models as random subjects. Correlation among successive measurements from each subject was accounted for using an autoregressive [AR(1)] variance-covariance structure. This approach enables correlation among residuals to decay exponentially over distance/time. The likelihood ratio test was used to evaluate the relative improvement in model fit when error structure was added through the “repeated” statement (Proc Mixed, SAS®). Nine predictor variables (age, sex, race, BMI, activity level, season, urine sample type, sequence of the participant’s voids over time, and ln(CR-level)) were used in the “urine” mixed model. Here, we treated the final urine samples on days 2 and 5 as bedtime voids, and the first sample on days 3 and 6 as FMVs. Initially, all predictors were regressed to ln(BPA) concentration. Manual backwards elimination of individual predictors was used to eliminate non-explanatory variables, and all predictors in the final model had a p < 0.05. All models converged with < 10 iterations. The equation for our final model was:

| (2) |

The first five terms are fixed effects, γ00, β1, β2, β3, and β4 are fixed coefficients, μ0j is random intercept representing deviations from population intercept for each subject, and the residuals rij ~ N (0, σ2).

There were a limited number of food samples (n = 775) and surface wipes samples (n = 138) that were collected over the six-week monitoring period (in comparison to the urine samples n = 2501). As such, separate mixed models were developed to focus on the relationship between these environmental measures and urinary BPA values. For the “food” model, the participants’ corresponding urinary sample data were averaged (arithmetic mean of natural-space values) over these same sampling time periods. Three types of food models were set to match the participants’ ln(BPA food levels) with their ln(urinary BPA levels): 1) Food Model A = the same time period (e.g., BPA food level during period 1 [4:00–11:00 am] compared to the average urinary BPA level during period 1 [4:00–11:00 am]); 2) Food Model B = the next time period (e.g., BPA food level in period 1 [4:00–11:00 am] compared with the average urinary BPA level in period 2 [11:00 am–5:00 pm]); and, 3) Food Model C = two time periods later (e.g., BPA food level in period 1 [4:00–11:00 am] compared with the average urinary BPA level in period 3 [5:00 pm–4:00 am]). In each type of food model (A, B, and C), we also included significant predictors as determined for the aforementioned “urine” regression model. For the “surface wipe” model, the participants’ ln(BPA surface wipe) data (day 4) were matched to their corresponding BPA bedtime urine data (day 4) by sampling week; again, significant predictors from the “urine” model were also included in this model. The goodness of model fit of each model was assessed by visualizing the residual diagnostic plots.

The adults’ estimated daily dietary intake doses of BPA were calculated by sampling week and overall using the equation by Morgan et al. (2016b):

| (3) |

where DF is the estimated daily dose by food intake (ng/kg/day), Ft is the level of BPA measured in the participant’s solid food sample (ng/g), Mt is the measured amount (g) of the solid food sample, A is the percent absorption of BPA (100%) in the gut (Volkel et al., 2002), and B is the participant’s body weight (kg). The subscript t signifies whether the food sample was collected during sampling periods 1, 2, or 3 each sampling day.

Two reverse dosimetry approaches were also used to estimate body weight-adjusted dose. The first approach utilized urine concentration measures and urine void volumes, as described in Eq. (4). Here, DEM is the estimated daily dose based on excreted mass (ng/kg/day), Cs is the measured concentration of BPA (ng/mL) in sample s, Vs is the total void volume (mL) of sample s, n is the total number of voids in a given 24-h period, E is the percent of BPA dose that is assumed excreted in urine (100%), and B is the participant’s body weight (kg).

| (4) |

This approach (Eq. (4)) is likely not appropriate for calculating BPA dose on sampling days when one or more urine voids were missed by a participant. To overcome this challenge, a second approach (Eq. (5)) utilized the average BPA excretion rate over each 24-h sampling period. This approach relies on the product of the average excretion rate (R in ng/min) and the exact duration of the sampling window (T in min) for a given participant-day, and produces the estimated daily dose (ng/kg/day) based on BPA excretion rate (DER).

| (5) |

Estimates of DEM and DER were compared across complete and incomplete collection days via scatterplots, Spearman’s rank-order correlations, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Estimates of DF, DEM (for complete collection days, only) and DER were compared using cumulative percentile plots and Spearman’s rank-order correlations.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics

Table 1 presents the demographics of the 50 Ex-R participants. The ages ranged from 19 to 50 years old, and 60% of the participants were female. The racial backgrounds of the participants were reported as Hispanic (13%), non-Hispanic black (25%), non-Hispanic white (56%), and other (6%). The BMI data indicated that 34%, 26%, and 40% of the participants were underweight/normal, overweight, and obese, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographics of the Ex-R adult participants.

| Characteristic | Na | %b |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 19–29 | 22 | 44 |

| 30–39 | 14 | 28 |

| 40–50 | 14 | 28 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 20 | 40 |

| Female | 30 | 60 |

| Racec | ||

| Hispanic | 6 | 13 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 11 | 25 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 25 | 56 |

| Otherd | 3 | 6 |

| BMIe | ||

| Underweight/normal (< 25.0) | 17 | 34 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 13 | 26 |

| Obese (≥ 30) | 20 | 40 |

Number of adults.

Percentage of adults.

Race information was collected from 45 out of 50 of the participants (Morgan et al., 2016a).

Other race category included one Native American and two Asians.

BMI (body mass index).

3.2. Environmental concentrations of BPA

BPA was detected in 38%, 4%, and 99% of all of the participants’ duplicate-diet solid food, drinking water, and hard floor surface wipe samples, respectively. The maximum BPA level in the drinking water was 0.062 ng/mL. Table 2 presents the distributions of BPA concentrations in the solid food and surface wipe samples (by week and total) over the six-week monitoring period. At the 75th percentile, BPA levels in the solid food samples were 2.00 ng/g (week 1), 2.20 ng/g (week 2), and 1.80 ng/g (week 6). The maximum BPA concentration across all solid food samples was 138 ng/g. For the surface wipes collected on the participants’ kitchen floors, median concentrations of BPA were 0.46 ng/cm2 (week 1), 0.56 ng/cm2 (week 2), and 0.46 ng/cm2 (week 6). The maximum BPA level across all surface wipe samples was 21.3 ng/cm2 – this maximum value was approximately two times higher than the next highest measured value (11.4 ng/cm2).

Table 2.

BPA levels in collected environmental media over the six-week monitoring perioda.

| Medium | Nb | %c | GM (GSD)d | Percentiles

|

Maximum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25th | 50th | 75th | 95th | 99th | |||||

| Duplicate-diet solid food (ng/g) | |||||||||

| Week 1 | 251e | 37 | –f | < | < | 2.00 | 17.2 | 52.5 | 91.6 |

| Week 2 | 263 | 38 | – | < | < | 2.20 | 22.3 | 104 | 138 |

| Week 6 | 261 | 38 | – | < | < | 1.80 | 13.0 | 56.2 | 63.1 |

| All | 775 | 38 | – | < | < | 2.00 | 17.2 | 60.9 | 138 |

| Hard floor surface wipes (ng/cm2) | |||||||||

| Week 1 | 44g | 100 | 0.54 (3.69) | 0.23 | 0.46 | 1.23 | 4.68 | 21.3 | 21.3 |

| Week 2 | 45h | 100 | 0.60 (3.09) | 0.24 | 0.56 | 1.49 | 4.14 | 8.19 | 8.19 |

| Week 6 | 49i | 98 | 0.51 (3.34) | 0.22 | 0.46 | 1.26 | 3.67 | 11.4 | 11.4 |

| All | 138 | 99 | 0.55 (3.35) | 0.22 | 0.54 | 1.28 | 4.14 | 11.4 | 21.3 |

BPA was detected in 4% of the drinking water samples (maximum value = 0.062 ng/mL).

Number of samples.

Percentage of samples at or above the limit of quantitation (LOQ).

Geometric mean and geometric standard deviation.

Two samples were excluded due to participant collection error.

Not reported because BPA was detected in < 50% of the solid food samples.

Six samples were lost due to a laboratory equipment malfunction.

Four samples were lost due to a laboratory equipment malfunction.

One participant did not provide a surface wipe sample due to a family emergency on week 6.

3.3. Urinary concentrations of BPA

Table 3 presents the distributions of total BPA levels by urine sample type (FMV, bedtime, 24-h, and total) as concentration, SG-adjusted, CR-adjusted, and excretion rate values for 50 Ex-R adults over a six-week monitoring period. BPA was detected in 98% of the total urine samples. For all of the urine samples, median BPA levels were 2.07 ng/mL, 2.20 ng/mL-SG, 2.29 ng/mg, and 2.31 ng/min for concentration, SG-adjusted, CR-adjusted, and excretion rate values, respectively. Results showed that median BPA concentrations were consistently the lowest in FMV samples (1.75 ng/mL, 1.63 ng/mL-SG, 1.64 ng/mg-CR, and 1.38 ng/min) and the highest in 24-h samples (2.12 ng/mL, 2.41 ng/mL-SG, 2.57 ng/mg-CR, and 2.67 ng/min) across all four methods. Similarly, at the 95th percentile BPA levels were the lowest in the FMV urine samples (9.30 ng/mL, 14.3 ng/mL-SG, 15.2 ng/mg-CR, and 12.6 ng/mL) and the greatest in the 24-h samples (12.6 ng/mL, 24.8 ng/mL-SG, 31.3 ng/mg-CR, and 31.5 ng/mL).

Table 3.

Urinary concentrations of BPA in 50 Ex-R adults over a six-week monitoring perioda.

| Sample typeb,c,d | Nf | GM (GSD)g | Min. | Percentiles

|

Max. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 95th | 99th | |||||

| FMVe | ||||||||||

| ng/mL | 294 | 1.83 (3.17) | < | 0.22 | 0.98 | 1.75 | 3.88 | 9.30 | 44.0 | 81.5 |

| ng/mL-SG | 293 | 1.67 (3.40) | < | 0.18 | 0.86 | 1.63 | 3.29 | 14.3 | 48.1 | 141 |

| ng/mg | 293 | 1.63 (3.62) | < | 0.17 | 0.83 | 1.64 | 3.41 | 15.2 | 58.3 | 133 |

| ng/min | 291 | 1.35 (3.63) | < | 0.13 | 0.63 | 1.38 | 2.81 | 12.6 | 56.6 | 134 |

| Bedtime void | ||||||||||

| ng/mL | 289 | 1.79 (3.26) | < | 0.18 | 0.96 | 2.04 | 3.66 | 10.2 | 20.5 | 38.2 |

| ng/mL-SG | 287 | 1.67 (4.11) | < | 0.13 | 0.73 | 1.87 | 3.70 | 18.4 | 40.5 | 94.9 |

| ng/mg | 287 | 1.78 (4.53) | < | 0.12 | 0.77 | 1.89 | 4.24 | 23.6 | 63.9 | 162 |

| ng/min | 284 | 1.71 (4.44) | < | 0.12 | 0.73 | 1.72 | 4.53 | 19.4 | 75.3 | 96.7 |

| 24-h sample | ||||||||||

| ng/mL | 1886 | 2.00 (3.41) | < | 0.23 | 1.00 | 2.12 | 4.20 | 12.6 | 35.9 | 1021 |

| ng/mL-SG | 1866 | 2.39 (4.06) | < | 0.24 | 1.03 | 2.41 | 5.21 | 24.8 | 88.6 | 2100 |

| ng/mg | 1866 | 2.65 (4.56) | < | 0.24 | 1.03 | 2.57 | 6.35 | 31.3 | 128 | 3262 |

| ng/min | 1875 | 2.70 (4.53) | < | 0.24 | 1.03 | 2.67 | 6.66 | 31.5 | 122 | 2832 |

| All | ||||||||||

| ng/mL | 2477 | 1.96 (3.36) | < | 0.22 | 0.99 | 2.07 | 4.12 | 12.2 | 34.7 | 1021 |

| ng/mL-SG | 2453 | 2.19 (4.01) | < | 0.21 | 0.99 | 2.20 | 4.73 | 23.3 | 73.6 | 2100 |

| ng/mg | 2453 | 2.38 (4.48) | < | 0.20 | 0.97 | 2.29 | 5.70 | 28.0 | 102 | 3262 |

| ng/min | 2457 | 2.36 (4.49) | < | 0.20 | 0.94 | 2.31 | 5.85 | 28.1 | 96.3 | 2832 |

Urine data are presented as unadjusted (ng/mL) and as specific-gravity (ng/mL-SG), creatinine (ng/mg), and excretion rate (ng/min) adjusted values.

BPA was detected in 98%, 97%, and 98% of the FMV, bedtime, and 24-h urine samples, respectively.

18 urine samples were excluded because they failed our quality control standards.

6 urine samples were not analyzed for BPA levels due to laboratory error.

FMV (first-morning void).

Number of urine samples.

Geometric mean and geometric standard deviation.

3.4. ICC estimates for repeated urinary BPA measurements

Table 4 provides estimates of between and within-person fold ranges and ICCs for repeated measurements of total BPA by urine sample type and method for the 50 Ex-R adults over a day, week, and six weeks. The results showed poor reproducibility (ICC < 0.40) for all urine sample types and methods over all time periods. In general, the ICC estimates for SG-adjusted, CR-adjusted, and excretion rate values for BPA were slightly greater than the ICC estimates for unadjusted values for BPA. Also in Table 4, the highest ICC value of 0.35 occurred for CR-adjusted bedtime voids collected over a week. However, to obtain a reliable average biomarker estimate (ICC = 0.80) for BPA, the results indicated that a minimum of eight bedtime urine voids (an unattainable number) would be needed for each adult over a week. CR-adjusted bedtime voids collected over six weeks required the fewest, realistic number of samples (n = 11) to obtain a reliable biomarker estimate.

Table 4.

Components of variance and other associated statistics for BPA concentrations in Ex-R adults by urine sample type and method over a day, week, and six weeks.

| Urine sample typea | Unadjusted (ng/mL)

|

SG-adjusted (ng/mL-SG)

|

CR-adjusted (ng/mg)

|

Excretion rate (ng/min)

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bR0.95 b | WR0.95c | ICCd | me | bR0.95 | WR0.95 | ICC | m | bR0.95 | WR0.95 | ICC | m | bR0.95 | WR0.95 | ICC | m | |

| One day | ||||||||||||||||

| 24-hf | 7.8 | 89.6 | 0.17 | 20 | 17.4 | 161 | 0.24 | 13 | 28.8 | 216 | 0.28 | 11 | 21.0 | 223 | 0.24 | 13 |

| One week | ||||||||||||||||

| FMV | 1.0 | 78.1 | 0.00 | –g | 1.0 | 133 | 0.00 | – | 1.0 | 166 | 0.00 | – | 1.0 | 142 | 0.00 | – |

| Bedtime | 10.5 | 68.0 | 0.24 | 13 | 25.6 | 90.4 | 0.34 | 8 | 33.6 | 122 | 0.35 | 8 | 18.3 | 176 | 0.24 | 13 |

| 24-h | 8.7 | 81.7 | 0.19 | 17 | 17.3 | 145 | 0.25 | 13 | 24.6 | 200 | 0.27 | 11 | 18.5 | 218 | 0.23 | 14 |

| Six weeks | ||||||||||||||||

| FMV | 3.9 | 75.4 | 0.09 | 41 | 4.3 | 97.1 | 0.09 | 40 | 5.9 | 113 | 0.12 | 29 | 6.0 | 113 | 0.13 | 28 |

| Bedtime | 6.8 | 68.1 | 0.17 | 20 | 16.0 | 122 | 0.25 | 12 | 23.1 | 152 | 0.28 | 11 | 16.6 | 168 | 0.23 | 14 |

| 24-h | 7.3 | 83.5 | 0.17 | 20 | 13.2 | 133 | 0.22 | 14 | 19.4 | 184 | 0.24 | 13 | 13.2 | 133 | 0.22 | 15 |

Bedtime void, first morning void (FMV) or 24-h sample.

Estimated between-person fold range.

Estimated within-person fold range.

Estimated ICC (intraclass correlation coefficient).

Number of random spot urine samples per adult likely required to have a reliable biomarker estimate (ICC = 0.80) (Fleiss, 1985).

Urine data values are limited to the first sampling period of week 1 as this interval had the highest participant completion rates over the six-week period.

Between-person variance was zero resulting in an ICC of zero, so a sample size could not be determined.

3.5. Predictors of urinary BPA concentrations

The results of our final mixed-effects “urine” model are presented in Table 5. Sex, race, season, and CR-level were all significant predictors (p < 0.05) of the participants’ urinary BPA concentrations. The levels of urinary BPA were significantly higher (p = 0.007) in female participants compared to male participants. The urinary BPA concentrations were also significantly different (p = 0.007) among the races with the highest concentrations observed in the Hispanic adults. In addition, the participants’ urinary BPA levels were significantly different (p < 0.0001) across the four sampling seasons with the greatest levels occurring in the winter season followed by the spring season. Also in this model (Table 5), CR-concentration had a significant (p = 0.0002) negative effect (β-coefficient = −0.131) on the participants’ urinary BPA concentrations. For the sake of comparison, we also re-ran the above “urine” model substituting the variable urine output (mL/min) for the variable CR-level. The final model had a similar outcome showing that sex, race, season, and urine output were all significant predictors (p < 0.05) of the adults’ urinary levels of BPA (Appendix B). However, the variable, ln(urine output), had a significant positive effect (p = 0.011, β-coefficient = 0.080) on ln(urinary BPA concentrations) –(we note that the correlation between ln(urine output) and ln(CR-level) was 0.83). While significant effects of CR-level and urine output were observed on urinary BPA concentrations, the effect sizes were generally small. For example, considering the reference group, non-Hispanic white males (in the summer), we estimate a BPA concentration of 0.74 ng/mL given a urine output of 0.1 mL/min, and a BPA concentration of 1.07 ng/mL given a urine output of 10 mL/min. So, a 100× change in urine output is expected to yield a < 2× change in urinary BPA concentration. When using the same reference group, we estimate a urinary BPA concentration of 1.2 ng/mL given a CR-concentration of 10 mg/dL, and a BPA concentration of 0.66 ng/mL given a CR-concentration of 1000 mg/dL. Therefore, a 100× change in CR-concentration is expected to yield a ~2× change in urinary BPA concentration. These results underscore a somewhat limited sensitivity of urinary BPA concentration to changing urine output and CR-level.

Table 5.

The final regression model of factors (excluding environmental media) influencing the adults’ urinary BPA levels.

| Factor | β-Coefficient | Standard error | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.484 | 0.204 | 0.019 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL)b | −0.131 | 0.035 | 0.0002 |

| Sexc | 0.007 | ||

| Female | 0.297 | 0.105 | |

| Male | 0 | – | |

| Racec | 0.007 | ||

| Hispanic | 0.526 | 0.163 | |

| Other | 0.311 | 0.144 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.272 | 0.134 | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 0 | – | |

| Seasonc | < 0.0001 | ||

| Winter | 0.596 | 0.135 | |

| Spring | 0.593 | 0.131 | |

| Fall | 0.253 | 0.130 | |

| Summer | 0 | – |

Statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Continuous variable (natural log-transformed).

Discrete variable.

As mentioned previously, since the solid food and surface wipe samples were collected on different sampling days, separate models were developed to examine relationships between these measures and urinary BPA levels. Three different types of food models (A, B and C) were used to examine the temporal influence of measured BPA levels in the solid food samples, and of other significant variables mentioned above (sex, race, season, and CR-level), on the variability of the adults urinary BPA concentrations (Appendix C). The results showed that BPA levels in the solid food samples did not contribute significantly to urinary BPA concentrations in all three models (p-values ranged from 0.458 to 0.841). Only the variable “CR-level” was a significant predictor (p < 0.05) of the adults’ urinary BPA concentrations across all three models. In a separate surface wipe model, we examined the collective influence of the measured BPA levels in the surface wipes, along with sex, race, season, and CR-level, on the variability of the adults’ urinary BPA concentrations (data not shown). The results showed that surface wipes collected in the participants’ kitchens were not significantly associated with urinary BPA levels (p = 0.233); only season (p = 0.012) and CR-level (p = 0.043) were significant predictors of the adults’ urinary BPA concentrations.

3.6. Forward and reverse dosimetry estimates for BPA

Table 6 provides the distributions of the estimated dietary intake doses (ng/kg/day) of BPA for the Ex-R adults by sampling week and overall. The participant’s estimated median dietary intake doses of BPA were similar across the three sampling weeks (week 1 = 10.7 ng/kg/day, week 2 = 10.3 ng/kg/day (week 2), and week 6 = 10.0 ng/kg/day). However, at the 95th percentile, the participants’ estimated dietary intake doses of BPA were at least two times higher for sampling week 2 (306 ng/kg/day) compared to sampling week 1 (107 ng/kg/day) and sampling week 6 (130 ng/kg/day).

Table 6.

The adults’ estimated dietary intake doses of BPA (ng/kg/day) by sampling week and overall.

| Sampling interval | Na | GMb | SDc | Min. | Percentiles

|

Max. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 95th | 99th | ||||||

| Week 1 | 42 | 13.2 | 2.94 | 1.20 | 1.70 | 6.90 | 10.7 | 21.7 | 107 | 267 | 267 |

| Week 2 | 42 | 15.0 | 3.79 | 0.80 | 3.30 | 7.00 | 10.3 | 30.5 | 306 | 774 | 774 |

| Week 6 | 42 | 13.2 | 3.86 | 0.10 | 3.10 | 6.10 | 10.0 | 24.7 | 130 | 447 | 447 |

| All | 42 | 13.7 | 3.52 | 0.10 | 2.90 | 6.80 | 10.3 | 27.7 | 167 | 409 | 774 |

Number of subjects. Dietary intake doses could not be estimated for 8 out of the 50 participants because their daily mass of food (g) eaten was not recorded in this study. A total of 238 individual solid food samples (representing 42 adults with up to six samples per person) were used for the dose estimates.

Geometric mean.

Geometric standard deviation.

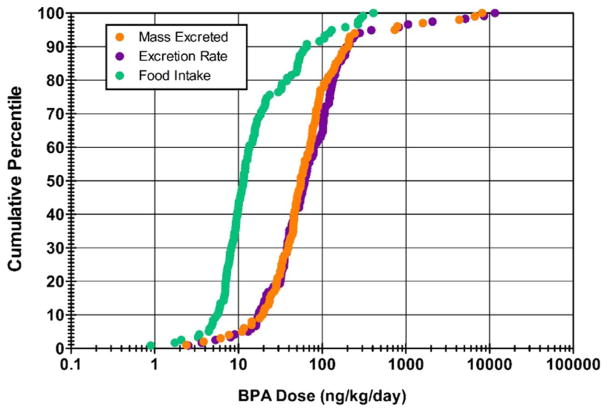

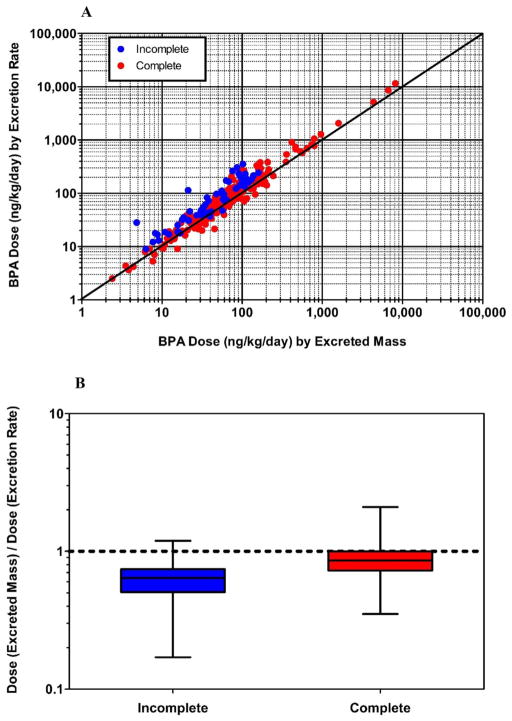

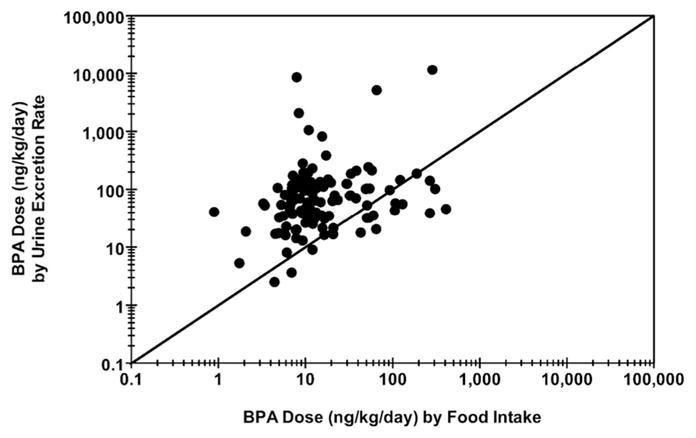

In Appendix D, Fig. D.1(A) shows a scatterplot of DEM (estimated dose based on excreted mass [ng/kg/day]) versus DER (estimated dose based on excretion rate [ng/kg/day]), with a differentiation made for complete and incomplete urine collection days. A strong linear relationship exists across estimates, regardless of completion status (Spearman’s Rho = 0.948; p < 0.0001 for complete days, only). Yet, an offset is also apparent for measures made on incomplete collection days, indicating an underestimation of BPA dose based on excreted mass. This effect of underestimation is shown more clearly in Appendix D (Fig. D.1(B)), where the ratio of DEM to DER is plotted separately for complete and incomplete collection days. Here, box-and-whiskers plots show a small but significant (p < 0.0001; Wilcoxon signed-rank test) underestimation of DER by DEM even on complete collection days (median ratio = 0.86). The even spread of the interquartile range (25th percentile = 0.72; 75th percentile = 1.00) and overall range (minimum = 0.35; maximum = 2.09), however, suggest that DEM may over- or underestimate DER to a similar degree, but often by no more than a factor of 2 in either direction. The box-and-whiskers plot for incomplete collection days (Fig. D.1(B)) shows a clear overall under-estimation of DER by DEM (median ratio = 0.64). Ratios determined for incomplete days were significantly lower than those determined for complete days (p < 0.0001; Wilcoxon rank-sum test). Furthermore, as indicated by the overall range (minimum = 0.17; maximum = 1.19), the magnitude of underestimation can be far greater (> 5×) on incomplete collection days when compared to complete collection days. Based on these results, only values of DEM for complete collection days are used for comparisons to DF. In contrast, all values of DER are used for subsequent dose estimate comparisons. In Appendix E, Fig. E.1 shows a scatterplot of DER versus DF (n = 119), and Fig. 2 (below) shows cumulative percentile plots of DER (n = 119), DF (n = 119), and DEM (n = 100). Measurements in each of these figures reflect only those participant-days during which solid food and urine samples were collected over a 24-h period. A significant positive correlation was observed between DER and DF (Spearman’s Rho = 0.25; p = 0.006). Yet, DF levels across the cumulative percentile distribution were considerably lower than DER and DEM. Whereas DER and DEM tracked reasonably well across the distribution, DF levels were generally about five times lower than either DER or DEM between the 25th and 75th percentiles. This indicates that BPA intake via ingestion of solid food comprised only a portion of the total dose, as estimated by urinary BPA measures (assuming 100% urinary excretion).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative percentile plots for adult BPA dose based on food intake (DF; n = 119), urinary excretion rate (DER; n = 119), and excreted mass in urine (DEM; n = 100).

4. Discussion

Previous research has indicated that dietary ingestion of BPA is a major route of exposure in non-occupationally exposed adults worldwide (Geens et al., 2012; Von Goetz et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2015). This is supported by several studies that have found measurable levels of BPA in total diet samples (typical diet of a population) or in specific food items (e.g., canned foods) purchased from grocery stores (Cao et al., 2011; Mariscal-Arcas et al., 2009; Noonan et al., 2011; Sajiki et al., 2007; Sakhi et al., 2014; Schecter et al., 2010). However, only a few published studies have measured BPA concentrations in the actual consumed diets (foods and beverages) of children (Wilson et al., 2001, 2003, 2007), and no studies have examined BPA in the consumed diets of adults. In our study, conducted in 2009–2011, drinking water and duplicate-diet solid food samples were collected from 50 adult participants in residential environments over a six-week monitoring period in NC (Table 2). BPA was not frequently detected (4%) in the drinking water samples (n = 50); therefore, this source was considered a minor contributor to the adults’ total dietary intake of BPA. Our result agrees with Arnold et al. (2013) who reported BPA levels were detected in < 10% of the drinking water samples in 34 different studies conducted in the US between 1990 and 2010. For the Ex-R duplicate-diet solid food samples, BPA was detected (LOD = 1.1 ng/g) in 38% of the 775 samples. At the 95th percentile (Table 2), BPA levels in the solid food samples were 17.2 ng/g, 22.3 ng/g, and 13.0 ng/g for weeks 1, 2, and 6, respectively. The maximum BPA concentration of 138 ng/g occurred in a female participant’s solid food sample during one sampling time period. This participant also had the highest maximum BPA level (288 ng/g) in her solid food samples over a 24-h sampling day. Based on this participant’s 24-h solid food data, the Ex-R adults’ maximum dietary intake dose of BPA (assuming 100% absorption) was 0.77 μg/kg/day. This maximum dietary intake dose was 65 times lower than the established oral reference dose of 50 μg/kg/day by the US EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS, 1988). However, the Ex-R adults’ maximum dietary intake dose of BPA was only 5 times lower than the recently modified Tolerable Daily Intake of 4 μg/kg/day (based on aggregate intake doses) by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA, 2015; LaKind and Naiman, 2015). Since duplicate-diet liquid food samples were not collected in the Ex-R study, we could not ascertain how much this source may have contributed to the participants’ total dietary intake doses of BPA. As the most comparable study, Wilson et al. (2007) did show that median levels of BPA were approximately eight times lower in 48-h duplicate-diet liquid food samples (~0.5 ng/g) compared to 48-h duplicate-diet solid food samples (~4.0 ng/g) for 256 children in NC and Ohio in 2000–2001. As data are scant, more research is necessary to quantify the temporal levels of BPA in the actual consumed diets of adults.

Research has indicated that non-dietary ingestion of dust and/or residues from residential flooring is likely a minor source of adult exposures to BPA (Geens et al., 2012). Only two cross-sectional studies were found in the literature that have measured BPA concentrations in surface wipes collected from hard floors at homes (Clifton et al., 2013; Wilson et al., 2007). Wilson et al. (2007) reported median BPA levels of ~0.05 ng/cm2 in surface wipes collected from various types of hard floors at 49 homes in NC and OH in 2000–2001. More recently, Clifton et al. (2013) showed slightly lower median BPA concentrations of 0.02 ng/cm2 in surface wipes collected from kitchen floors at 130 residences in California in 2007–2009. In comparison to the Ex-R study, our median levels of BPA (0.54 ng/cm2) in 138 hard floor surface wipe samples were an order of magnitude higher than median BPA levels reported in the two prior studies. This is likely attributed to differences in the amount of isopropanol used for the Ex-R wipes (10 mL each) compared to the two previous study wipes (≤3 mL each). For our study, using a one-way random effects mixed model, the estimated ICC was 0.79, indicating that a single surface wipe measurement was likely sufficient to characterize the average BPA level on kitchen floors at homes.

Many studies in the US have frequently detected total BPA in the urine of non-occupationally exposed adults in the last decade (Braun et al., 2011; Cantonwine et al., 2015; CDC, 2017; Cox et al., 2016; Philippat et al., 2013; Pollack et al., 2016; Quiros-Alcala et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2015). Our study also frequently detected total BPA (98%) in the urine of Ex-R adults, with a geometric mean (GM) level of 1.96 ng/mL. In comparison to our study, the 2009–2010 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES), a US population-based study, reported slightly lower GM BPA concentrations of 1.79 ng/mL for adults, 20 years of age or older (CDC, 2017). Recently, LaKind and Naiman (2015) showed that GM levels of urinary BPA have significantly decreased for NHANES adults over the past decade (2003–2004 survey, GM = 2.6 ng/mL versus 2011–2012 survey, GM = 1.5 ng/mL). Ye et al. (2015) also showed a significant decline in GM urinary BPA concentrations in a convenience sample of 616 adults in Georgia between 2010 (2.1 ng/mL) and 2014 (0.4 ng/mL). In other studies (2007–2014), conducted outside the contiguous US including Canada, China, Denmark, Germany, Israel, Korea, and Puerto Rico, median urinary BPA levels have ranged from 1.0–3.0 ng/mL in adults (Berman et al., 2014; Fisher et al., 2015; Huo et al., 2015; Kasper-Sonnenberg et al., 2012; Lassen et al., 2013; Meeker et al., 2013; Park et al., 2017). This information confirms there is still widespread exposure of adults to BPA worldwide.

In the Ex-R study, our ICC estimates showed poor reproducibility (< 0.40) of repeated measurements of BPA in the urine samples of adults for all urine sample types (FMV, bedtime, or 24-h) and methods (unadjusted and adjusted) over a day, week, and six weeks. Our results agree with other published studies (Table 7) that have also reported low ICC values for serial measurements of BPA in adults, globally. In the above studies, these low ICC estimates are likely attributed to the episodic exposures of adults to BPA (from various sources) and to its short biological half-life (< 6 h) in the body (Meeker et al., 2013; Volkel et al., 2002). In addition, these low ICC values provide substantial evidence that a single measure of urinary BPA is probably not sufficient to characterize the average short- or long-term exposures of adults in non-occupational settings. In our study, depending on the urine sample type and method used, the results (Table 4) indicated that between 8 and 41 samples would be necessary to obtain a reliable BPA biomarker estimate for an adult over a day, week, or six weeks. CR-adjusted bedtime voids collected over six weeks required the fewest, realistic number of samples (n = 11) to obtain a reliable biomarker estimate. This information suggests that bedtime voids may be the preferred sample type to collect in future studies to adequately assess the BPA exposures in adults.

Table 7.

Comparison of ICC estimates of urinary BPA concentrations in non-occupationally exposed adults worldwide.

| Country | Study year | Gender | Na | Sampling methodology | Sample type | ICC

|

Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ng/mL | ng/mL- SG | ng/mg | |||||||

| Belgium | 2012 | Men & women | 8 | All voids over four (baseline) days | Spot | 0.15 | – | 0.26 | Koch et al. (2014) |

| 24-h | 0.15 | – | 0.28 | ||||||

| Canada | 2009–2010 | Women | 80 | Two spot & two 24-h samples during pregnancy & one spot post-partum | Spot | 0.06 | 0.05 | – | Fisher et al. (2015) |

| 24-hb | 0.32 | 0.32 | – | ||||||

| China | 1997–2006 | Men & women | 100 | Three spot samples between 0 and 9 years apart | Spot (M)c | 0.32 | – | 0.25 | Engel et al. (2014) |

| Spot (F) | 0.07 | – | 0.13 | ||||||

| Denmark | 2008 | Men | 33 | Two spot, three FMV, & three 24-h samples over three months | FMV | 0.10 | – | – | Lassen et al. (2013) |

| Spot | 0.42 | – | – | ||||||

| 24-h | 0.26 | – | 0.26 | ||||||

| Netherlands | 2004–2006 | Women | 80 | Three spot samples during pregnancy | Spot | 0.32 | – | 0.31 | Jusko et al. (2014) |

| Norway | 2007–2008 | Women | 30 | Three spot samples during pregnancy | Spot | 0.36 | – | 0.13 | Guidry et al. (2015) |

| Puerto Rico | 2010–2012 | Women | 105 | Three spot samples during pregnancy | Spot | 0.27 | 0.24 | – | Meeker et al. (2013) |

| United States | 1996–2001 | Women | 80 | Two FMVs between 1 and 3 yrs. apart | FMV | – | – | 0.15 | Townsend et al. (2013) |

| United States | 2003–2006 | Women | 389 | Two spot samples during pregnancy & one after birth | Spot | 0.25 | – | 0.10 | Braun et al. (2011) |

| United States | 2004–2009 | Women | 137 | Two or more spot samples before and during pregnancy | Spot | – | 0.23e | – | Braun et al. (2012) |

| United States | 2005–2007 | Women | 143 | Three to five spot samples over two months | Spot | 0.04 | – | 0.04 | Pollack et al. (2016) |

| United States | 2005–2008 | Women | 71 | Three spot samples during pregnancy | Spot | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.14 | Philippat et al. (2013) |

| United States | 1992–2007d | Women | 90 | Two to three FMVs 1 and 3 yrs. apart | FMV | 0.09 | – | –f | Reeves et al. (2014) |

| United States | 2012 | Men & women | 83 | Seven FMVs for one week (males) | FMV | 0.15 | – | – | Cox et al. (2016) |

| 14–18 FMVs for two weeks (females) | FMV | ||||||||

| United Statesg | 2009–2011 | Men & women | 50 | Six spots (FMVs and bedtime) & six 24-h samples over a six-week period | FMV | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.12 | This study |

| Bedtime | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.28 | ||||||

| 24-h | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.24 | ||||||

Number of adults.

Combined data for samples collected on both weekdays and weekends.

Data for 50 males (M) and 50 female (F) reported separately.

These data are from the Women Health Initiative conducted between 1992 and 2007. Data were taken on year 1 and 3 to compare urine data results.

Before pregnancy samples, only.

Authors reported similar ICCs estimates for creatinine-adjusted values as unadjusted values (ICC = 0.09) in this study, but actual data not provided.

Data shown for only ICC estimates over six-weeks, only.

At least three different mechanisms are believed to control renal elimination of xenobiotic compounds – namely, passive diffusion, filtration and active secretion (Boeniger et al., 1993). Research has indicated that CR is mainly eliminated by renal filtration, and that the rate of excretion (mass/time) is relatively constant (Boeniger et al., 1993). For this type of mechanism, as urine output decreases, CR concentration (mass/volume) increases. Similar elimination mechanisms are believed to govern renal removal of a number of organic chemicals. In the current investigation, however, we found that BPA excretion does not track with CR-excretion – that is, a positive association was not observed between urinary BPA and urinary CR-concentrations. Interestingly, it appears that BPA excretion is somewhat dependent on urine output – meaning as urine output decreases, BPA excretion decreases, or as urine output increases, BPA excretion increases. The consequence of this physiological behavior is less within-person variability in BPA concentration measures when compared to SG- or CR-adjusted levels, or BPA excretion rate levels (as shown in Table 4). By adding additional adjustments for CR, SG, or urine output, it appears that we are introducing variability into the measurements –variability that is likely independent of the actual BPA exposure in question. This variability may help “separate” individuals (in terms of biomarker “reliability”), but the separation is being driven by factors other than BPA exposure. According to Table 4, we observed more between- and within-person variability for urinary BPA when using SG-adjusted, CR-adjusted, and excretion rate values compared to unadjusted concentration values. We also observed a disproportionate increase in between-person variability, which causes larger ICC values and lower “m” values. It is likely that the elevated between-person variance in SG-adjusted, CR-adjusted, and excretion rate levels stems from real between-person differences in CR-elimination (differences based on diet, body mass, etc.) and/or urine output (differences based on fluid intake, activity level, etc.). These biological phenomena are independent of BPA exposure. Thus, inherent biases may exist when using any of these “adjusted” values, despite the benefit of higher ICC and lower “m” values. Therefore, fewer urine samples may be needed when using CR-adjusted, SG-adjusted, or excretion rate measures, but these measures may potentially yield less accurate information about adult exposures to BPA when compared to concentration measures. This information implies that CR-adjusted, SG-adjusted and excretion rate values may be more “reliable”, but unadjusted BPA concentration measures may be more accurate. Additional research is needed to understand the factors and processes that govern renal elimination of environmental chemicals, including BPA, that are routinely monitored in human urine.

Results of our final “urine” model (excluding non-environmental matrices) showed that significant predictors (p < 0.05) of the Ex-R adults’ urinary BPA concentrations were sex, race, season, and CR-level (Table 5). Of these factors, season of collection was the strongest predictor (p < 0.0001) of urinary BPA levels in Ex-R adults. Interestingly, the participant’s urinary BPA levels were the highest in the winter season and the lowest in the summer season, but the reason for this remains unclear. Further research is therefore needed to determine the reason(s) for the seasonality of urinary BPA levels. In addition, we found that female participants had significantly higher urinary levels of BPA than male participants in this study. LaKind and Naiman (2015) also reported that sex was a strong predictor of urinary BPA levels in NHANES participants (2003–2010 survey years). In our subsequent regression models, we showed that BPA levels in solid food or surface wipes were not significant predictors of the adults’ individual urinary BPA levels. However, when considering measures aggregated over 24-h periods, a significant positive relationship was observed between solid food intake and urine-based estimates of BPA dose. This association was found to exist even though urine-based dose estimates were about five times larger than food-based estimates. As such, BPA in consumed solid food does appear to contribute to a portion of the aggregate urine measures. Specifically, dose estimates based on food intake (DF median = 11.5 ng/kg/day) were about 20% of those based on urinary BPA measures (DEM median = 55.4 and DER median = 61.8 ng/kg/day) (Fig. 2). This is an important finding as dietary ingestion is currently considered the dominant exposure route (> 90%) in adults (Geens et al., 2012; Von Goetz et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2015). In support of our finding, LaKind and Naiman (2015) recently reported, using urinary biomonitoring data, a significant decline in the estimated median BPA intakes of NHANES participants from the 2003–2004 survey (~50 ng/kg/day) to the 2011–2012 survey (~25 ng/kg/day). It is suspected that this observed decrease in the dietary intakes of BPA in US adults is partly attributed to the removal of BPA from some food packaging (e.g., can linings) by some US companies starting in the late 2000s (GCCM, 2010; Ye et al., 2015).

5. Conclusion

Based on the urinary biomonitoring data, the results showed that all the Ex-R adults were temporally exposed to BPA in residential settings over a six-week monitoring period in NC 2009–2011. Poor reproducibility (< 0.40) of repeated measurements of BPA occurred in the participants’ urine samples for all sample types, methods and time frames. Specific factors (sex, race, season, and CR-level) were identified that significantly impacted the participants urinary BPA concentrations. We found that dietary ingestion of BPA via solid food only accounted for ~20% of the total intake dose of BPA (at the median of the dose distribution) in Ex-R adults. This above information suggests that these adults were likely exposed to other major unidentified (non-diet) sources of BPA.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Carry Croghan for her technical assistance with the Ex-R study database and associated datasets. We would also like to thank Lillian Alston, Fu-Lin Chen, Richard Walker, and Erik Andersen for their technical assistance during this study. This work was funded in whole by the US EPA. Disclaimer: “The US EPA through its Office of Research and Development funded and managed the research described here. It has been subjected to Agency review and approved for publication. Although this work was reviewed by US EPA and approved for publication, it may not necessarily reflect official Agency policy. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.”

Abbreviations

- BPA

bisphenol-A

- BMI

body mass index

- CR

creatinine concentration

- EPA

US Environmental Protection Agency

- Ex-R study

A Pilot Study to Estimate Human Exposures to Pyrethroids using an Exposure Reconstruction Approach

- LC/MS/MS

liquid chromatograph - tandem mass spectrometer

- HSF

Human Studies Facility

- FMV

first-morning void

- GC/MSD

gas chromatograph-mass selective detector

- GM

geometric mean

- ICC

intraclass correlation coefficient

- LOQ

limit of quantitation

- NHANES

National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey

- NC

North Carolina

- QC

quality control

- QuEChERS

quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe method

- RTP

Research Triangle Park

- SG

specific gravity

- SRS

surrogate recovery standard

- UPS

United Parcel Service

- US

United States

Appendix A

The quality assurance and quality control procedures (including results) used for the solid food, drinking water, surface wipe, and urine samples are described below.

Duplicate-diet solid food

Matrix blank, matrix spike and recovery spike samples were prepared using a previously made homogenized control food mixture (5% fat) that contained mainly organic food items to decrease background residues of the target pyrethroids (not BPA) (Rosenblum et al., 2001; Morgan et al., 2016a). Replicates of this control food mixture (12 g each) were stored in individual 30 mL amber glass jars and kept in laboratory freezers (−20 °C) until needed. The three types of quality control (QC) samples (above) were prepared using the same jar of control food mixture (12 g). The BPA concentration in the spiked samples was determined by subtracting the background concentration found in the matrix blank. The matrix spikes in food (added before extraction) had a mean percent recovery of 99.5 ± 5.5 (one of 49 samples were excluded due a matrix effect). The mean percent recovery of the BPA spikes added after extraction- was 82.1 ± 6.8 (one of 50 samples were excluded because of an internal standard spiking error). In addition to the matrix-based QC samples, a reagent blank was prepared to assess background levels occurring in lab ware or during sample preparation procedures. Low background levels of BPA occurred in 21% of the reagent blank samples, so background correction in the field samples was necessary. The mean relative percent difference was 9.0 ± 11.4 in duplicate food samples (aliquots of the same field sample). For analytical duplicates (extracts of the same sample), the mean relative percent difference was 3.0 ± 4.1.

Drinking water

All field and laboratory blanks were below the LOQ for BPA. The field spikes had a mean percent recovery of 104 ± 3.8 for BPA (two of six samples were excluded due to spiking errors). For the matrix spikes, the mean percent recovery for BPA was 102 ± 9.0. The SRS results were variable with a mean percent recovery of 117 ± 32.0 (10 additional samples were excluded due to technician laboratory error).

Hard floor surface wipe

All field and laboratory blanks for BPA were below the LOQ. For the field spikes, the mean percent recovery for BPA was 114 ± 7.8 (one additional sample was excluded because no spike was added). The mean percent recovery for the matrix spikes was 99.8 ± 6.7, and the mean percent recovery for the SRS was 92.6 ± 16.3.

Urine

Field and laboratory blanks consisted of pooled urine samples from adult volunteers (Morgan et al., 2016a). Low background levels of BPA occurred in all field blanks (mean = 0.19 ± 0.05 ng/mL) and laboratory blanks (mean = 0.14 ± 0.08 ng/mL). This likely resulted from true background levels of BPA occurring in the pooled urine samples (not sample contamination), therefore, background correction was not made. For the field spikes, a percent relative standard deviation of 1% was observed for BPA. In addition, all reagent blanks were below the LOQ for BPA. For duplicate samples (aliquots of the same urine sample), the mean relative percent difference was 19.6 ± 14.9 for BPA. Lastly, all QC samples had to be within ± 20 of the spiked level for each analytical run to be acceptable (Morgan et al., 2016a).

Appendix B

Table B.1.

The final regression model of factors (excluding environmental media) influencing the adults’ urinary BPA levels.

| Factor | β-Coefficient | Standard error | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.117 | 0.138 | 0.397 |

| Urine output (mL/min)b | 0.080 | 0.031 | 0.011 |

| Sexc | 0.004 | ||

| Female | 0.324 | 0.107 | |

| Male | 0 | – | |

| Racec | 0.017 | ||

| Hispanic | 0.481 | 0.164 | |

| Other | 0.294 | 0.145 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.226 | 0.135 | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 0 | – | |

| Seasonc | < 0.0001 | ||

| Winter | 0.610 | 0.136 | |

| Spring | 0.602 | 0.133 | |

| Fall | 0.274 | 0.130 | |

| Summer | 0 | – |

Statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Continuous variable (natural log-transformed).

Discrete variable.

Appendix C

Table C.1.

The final linear mixed-effects models examining the impact of BPA levels in solid food and other selected variables on urinary BPA levelsa.

| Factors | Food Model A

|

Food Model B

|

Food Model C

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Coefficient | Standard error |

p-Value | β-Coefficient | Standard error |

p-Value | β-Coefficient | Standard error |

p-Value | |

| Intercept | 1.877 | 0.538 | 0.0006 c | 1.623 | 0.614 | 0.009 | 2.002 | 0.717 | 0.006 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL)b | −0.370 | 0.107 | 0.0007 | −0.302 | 0.121 | 0.013 | −0.371 | 0.145 | 0.012 |

| Solid foodb | −0.044 | 0.060 | 0.458 | −0.013 | 0.064 | 0.841 | −0.054 | 0.080 | 0.499 |

| Sexd | 0.063 | 0.035 | 0.039 | ||||||

| Female | 0.294 | 0.157 | 0.375 | 0.173 | 0.455 | 0.213 | |||

| Male | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | |||

| Raced | 0.0008 | 0.179 | 0.090 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 0.927 | 0.252 | 0.169 | 0.283 | 0.875 | 0.348 | |||

| Other | 0.560 | 0.204 | 0.474 | 0.225 | 0.187 | 0.262 | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.352 | 0.191 | 0.311 | 0.212 | 0.360 | 0.266 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | |||

| Seasond | 0.020 | 0.219 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Winter | 0.452 | 0.193 | 0.293 | 0.225 | 0.352 | 0.259 | |||

| Spring | 0.6260.139 | 0.229 | 0.490 | 0.259 | 0.850 | 0.304 | |||

| Fall | 0.139 | 0.221 | 0.066 | 0.254 | −0.362 | 0.309 | |||

| Summer | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | |||

The types of food models (A–C) were set to relate the participant’s BPA solid food levels with their urinary BPA levels over time: Food Model A = the same time period (e.g., BPA food level during period 1 with average urinary BPA level during period 1); 2) ood odel B = the next time period (e.g., BPA food level in period 1 with urinary BPA level in period 2); and, ood odel C = two time periods later (e.g., BPA food level in period 1 with urinary BPA level in period 3). Urine was log-transformed.

Continuous variable (log-transformed).

Statistically significant variables (p < 0.05) are in bold text.

Discrete variable.

Appendix D

Fig. D.1.

Comparison of urinary BPA dose estimates by excreted mass versus excretion rate (A). BPA dose ratio for complete and incomplete 24-h voids (B).

Appendix E

Fig. E.1.

Comparison of BPA dose estimates by food intake versus urine excretion rate. Spearman’s Rho = 0.25; p = 0.0064.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- ACC (American Chemistry Council) [accessed 09 May 2017];About bisphenol A. 2015 http://www.bisphenol-a.org/about/

- Anastassiades M, Lehotay SJ, Stajnbaher D, Schenck FJ. Fast and easy multiresidue method employing acetonitrile extraction partitioning and dispersive solid phase extraction for determination of pesticide residues in produce. J AOAC Int. 2003;86:412–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen EM, Sobus JR, Strynar MJ, Pleil JD, Nakayama SF. Evaluating an alternative method for rapid urinary creatinine determination. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2014;77:1114–1123. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2014.922391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SM, Clark KE, Staples CA, Klecka GM, Dimond SS, Caspers N, et al. Relevance of drinking water as a source of human exposure to bisphenol A. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2013;23:137–144. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman T, Goldsmith R, Goen T, Spungen J, Novack L, Levine H, et al. Demographic and dietary predictors of urinary bisphenol A concentrations in adults in Israel. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2014;217:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeniger MK, Lowry LK, Rosenberg J. Interpretation of urine results used to assess chemical exposure with emphasis on creatinine adjustments: a review. Am Ind Hyg Assoc. 1993;54:615–627. doi: 10.1080/15298669391355134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Kalkbrenner AE, Calafat AM, Bernert JT, Ye X, Silva MJ, et al. Variability and predictors of urinary bisphenol A concentrations during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:131–137. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Smith KW, Williams PL, Calafat AM, Berry K, Ehrlich S, et al. Variability of urinary phthalate metabolite and bisphenol A concentrations before and during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:739–745. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantonwine DE, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, McElrath T, Meeker JD. Urinary bisphenol A levels during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:895–901. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao XL, Perez-Locas C, Dufresne G, Clement G, Popovic S, Beraldrin F, et al. Concentrations of bisphenol A in the composited food samples from the 2008 Canadian total diet study in Quebec City and dietary intake estimates. Food Addit Contam. 2011;28:791–798. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2010.513015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) [accessed 09 May 2017];Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals; Updated Tables. 1 ( https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/pdf/FourthReport_UpdatedTables_Volume1_Jan2017.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton MS, Wargo JP, Weathers WS, Colon M, Bennett DH, Tulve NS. Quantitative analysis of organophosphate and pyrethroid insecticides, pyrethroid transformation products, polybrominated diphenyl ethers and bisphenol A in residential surface wipe samples. J Chromatogr A. 2013;273:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton MS, Wargo JP, Morgan MK. A robust, high throughput method for measurement of triclosan and bisphenol A residues in duplicate diet samples. Published Abstract at the 36th National Meeting of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry; Salt Lake City, UT. 2015. [Google Scholar]