Abstract

The development and application of physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models in chemical toxicology have grown steadily since their emergence in the 1980s. However, critical evaluation of PBPK models to support public health decision-making across federal agencies has thus far occurred for only a few environmental chemicals. In order to encourage decision-makers to embrace the critical role of PBPK modeling in risk assessment, several important challenges require immediate attention from the modeling community. The objective of this contemporary review is to highlight 3 of these challenges, including: (1) difficulties in recruiting peer reviewers with appropriate modeling expertise and experience; (2) lack of confidence in PBPK models for which no tissue/plasma concentration data exist for model evaluation; and (3) lack of transferability across modeling platforms. Several recommendations for addressing these 3 issues are provided to initiate dialog among members of the PBPK modeling community, as these issues must be overcome for the field of PBPK modeling to advance and for PBPK models to be more routinely applied in support of public health decision-making.

Keywords: physiologically based pharmacokinetic model, good modeling practice, risk assessment, intraspecies extrapolation, interspecies extrapolation

A HISTORY OF PBPK MODELING

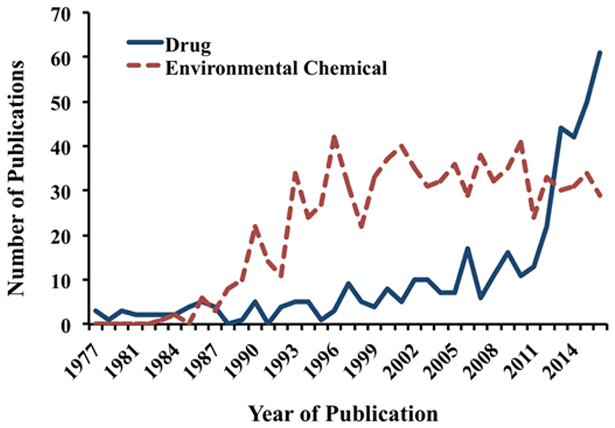

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is a valuable tool that arose from the recognition that concentrations of chemicals at target tissues are more predictive of biological responses than are external doses (US EPA, 2006; WHO, 2010). PBPK models have been applied to organize and integrate mechanistic data, to generate hypotheses and to drive new experimental studies (Abaci and Shuler, 2015; Claassen et al., 2015; Bachler et al, 2013), to characterize physiological and pharmacokinetic variability and uncertainty (Barton et al., 2007; Beaudouin et al., 2010; Bois et al., 2010; Fierens et al., 2016; Worley et al., 2017), to support aggregate exposure assessment (Kenyon et al., 2016), to extrapolate across species, life stages, exposure routes and timing (Andersen et al., 1987; Gentry et al., 2017a; Shankaran et al., 2013; Weijs et al., 2012; Yoon and Clewell, 2016), and to interpret biomonitoring data or epidemiologic studies (Brown et al., 2015; McNally et al., 2012; Verner et al., 2015). The number of published PBPK models has increased significantly over the past 3 decades. A literature search conducted in July 2017, using the PubMed database with search terms “PBPK OR physiologically based AND pharmacokinetic OR toxicokinetic”, revealed that the first published PBPK models were primarily developed for pharmaceutical compounds in the 1970s, followed by those for environmental chemicals in the mid1980s (Figure 1). Although the number of published models for environmental chemicals quickly outnumbered those for drugs, the latter has recently seen a sharp increase (Figure 1). Of the 1313 references describing PBPK models from 1977 to 2016, the majority involved environmental chemicals (65%), followed by drugs (31%), with the remaining 4% involving endogenous compounds (eg, monoclonal antibodies, small peptides).

Figure 1.

Number of articles referencing physiologically based pharmacokinetic models for drugs or environmental chemicals that have been published over the last several decades. The keyword search included “pbpk OR (“physiologically based” AND (pharmacokinetic OR toxicokinetic”, resulting in articles first identified in 1977 in the PubMed literature database.

CURRENT STATUS OF PBPK MODELING IN DECISION-MAKING PRACTICES

Analysis of the extent to which PBPK modeling is currently incorporated into federal level decision-making can shed light on the level of interest in applying PBPK models in the public health arena. The Federal Register (FR) publishes rules, proposed rules, and notices from federal agencies in an effort to inform the public of changes to government policies and guidelines. Thus, the listings found in the FR can serve as a barometer for evaluating recent public health actions involving PBPK models across the federal agencies.

A search of the FR in July 2017 in the repositories Regulations.gov and HeinOnline, using the search term “PBPK” with options for “proposed rules, final rules, other, and supporting material”, returned 314 related documents spanning from 1988 to 2017 (Table 1). Nearly a quarter of these documents were published either by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). A majority of the identified documents for each agency, other than the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), did not involve rulemaking. In addition, many PBPK-related FR entries for some agencies, such as the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), referred to the PBPK modeling efforts conducted by other agencies.

Table 1.

Numbers of Agency Submissions of FR Documents That are Identified Using the Keyword “PBPK”

| Federal Agencies | Rule Making | Nonrule Making | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDA | 24 | 65 | 89 |

| EPA | 25 | 56 | 81 |

| OSHA | 58 | 4 | 62 |

| ATSDR | 13 | 24 | 37 |

| National Highway Traffic Safety Administration | 20 | 10 | 30 |

| The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| Mine Safety and Health Administration | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 142 | 172 | 314 |

Several FR documents alluded to PBPK modeling in the context of precluding its use in risk assessment due to the limitations and uncertainties perceived or inherent in model development and/or application. For example, a FR document issued by the EPA concluded that a published PBPK model for perchlorate cannot be used when establishing a maximum contaminant level in drinking water due to issues such as inconsistencies in model code, lack of inclusion of a sensitive population, and uncertainties in animal-to-human extrapolation (FR, 2016a). Reasons listed in this example along with other reasons, such as low confidence in a model’s capability to characterize intra-species variability or to extrapolate to conditions in which no data exist for evaluation, represent some common concerns raised by risk assessors.

The EPA is 1 of the 2 agencies that issued the most PBPK-related FR entries (Table 1), with 25 of the 81 entries relating to either proposed or final rules for nearly 40 environmental chemicals. Since 2014, PBPK modeling has been central to risk assessment for several chemicals as suggested by the FR notices that requested experts in PBPK modeling. For example, the Office of Water requested reviewers with extensive PBPK modeling experience for evaluation of perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate (FR, 2014), as well as perchlorate (FR, 2016b). The Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) program requested peer reviewers with expert knowledge of PBPK modeling to act as members of the Science Advisory Board committee for assessing health risks from exposure to hexahydro-1, 3, 5-trinitro-1, 3, 5-triazine (FR, 2016c), as well as exposure to tert-butyl alcohol, and ethyl tertiary butyl ether (FR, 2016d). In another example, under the Toxic Substances Control Act, a rule was proposed to regulate vapor degreasing that involved acute risk assessment of trichloroethylene, based on PBPK-derived hazard values (FR, 2017).

The observation that only few PBPK-related FR documents involve the direct applications of PBPK modeling in risk assessment suggests that even though public health agencies acknowledge the potential benefits offered by PBPK modeling, many barriers still exist to the adoption and application of these models to support decision-making. To further explore these barriers, a query was conducted in July 2017 within EPA’s IRIS program (https://www.epa.gov/iris; last accessed December 7, 2017) using the keywords “PBPK” OR “PBTK” (TK stands for toxicokinetic) to review how PBPK modeling was used or not used in risk assessment. It was found that 50 out of the 511 (approximately 10%) available records reference PBPK modeling. In total, 9 of the 50 records involved the use of PBPK models to derive reference dose and/or reference concentration values (eg, for trichloroethylene, methanol, vinyl chloride), mainly through converting animal points of departure to equivalent human exposure levels, or extrapolating from one exposure route to another. Three records used PBPK models indirectly as in risk assessment (https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/iris_documents/documents/toxreviews/0020tr.pdf; last accessed December 7, 2017; https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/iris_documents/documents/toxreviews/0270tr.pdf; last accessed December 7, 2017; https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/iris_documents/documents/toxreviews/1011tr.pdf; last accessed December 7, 2017), such as comparing model predictions with a calculated no-observed-adverse-effect-level in the case of xylene. Twenty records suggested that PBPK models may be used to support risk assessment in the future when they become available. Eighteen records concluded that existing PBPK models were inappropriate for use by the agency. The reasons behind these conclusions varied, but primarily involved (1) inadequate model structure or parameterization for proper route-to-route or interspecies extrapolation; (2) inadequate description of the pharmacokinetics of active metabolites; and (3) the lack of human time-concentration data necessary for model evaluation.

In addition to supporting the derivation of guidance levels, considerable research efforts have occurred within federal agencies into the development and application of PBPK models in improving risk assessment (Chiu et al., 2009; Chiu and Ginsberg, 2011; DeWoskin et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2015; Leonard et al., 2016; Leong et al., 2012; McLanahan et al., 2012; Worley et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2011). PBPK models are also being applied to provide insight into potential health concerns from site-specific exposures to environmental chemicals. For example, in response to community concerns about benzene exposures in Corpus Christi, Texas, ATSDR re-coded a published PBPK model (Yokley et al., 2006) to predict internal dose metrics (Mumtaz et al., 2012; Ruiz et al., 2011) from various inhalation exposure scenarios. Results from this model led to the conclusion that the internal dose metric from seasonal residential exposure is 2 orders of magnitude lower than that at the level of the chronic inhalation minimal risk level and at the occupational exposure level (ATSDR, 2016).

The large gap between the numbers of PBPK-related publications (approximately 1300 from searches in PubMed) and FR notices or IRIS registries (<400) may be due to several factors. First, PBPK models developed for specific academic purposes are often not directly usable by public health agencies because model scope, assumptions, and inputs/outputs are not tailored to the specific needs of these agencies. Second, thorough vetting of model structure, biological characterization, parameter values, computational implementation, and predictive capabilities are required by public health agencies reviewing these models (McLanahan et al., 2012; US EPA, 2006; WHO, 2010) due to the significant impacts the use of such models might have on public health decisions. Third, expertise in pharmacokinetic or PBPK modeling concepts is often scarce within the public health agencies. In this contemporary review, 3 specific issues that were identified within this workshop are discussed in the following sections.

KEY ISSUE 1: CHALLENGES IN MODEL REVIEW

Application of PBPK models offers great potential for informing critical decisions related to public health concerns, but decision-makers who are interested in applying these models often encounter significant challenges in model review.

A shortage of individuals with sufficient training to shepherd a modeling project from problem formulation and biological characterization, through model development and coding, to applications in risk assessment (Barton et al., 2007).

A shortage of independent reviewers with sufficient expertise and experience in PBPK modeling and risk assessment to adequately evaluate, in a timely manner, the validity of conclusions based on PBPK modeling (Chiu et al., 2007).

A lack of consistent or standardized review or submission processes existing across different agencies (Paini et al., 2017).

Very few academic programs offer a curriculum that includes PBPK modeling and application, though some limited training opportunities do exist through specialized workshops (eg, Colorado State University, Kansas State University, University of Buffalo, Virginia Commonwealth University, ScitoVation). Such alternative training options, however, typically do not fit within a traditional academic paradigm and are often inaccessible to students in graduate training programs. Additionally, limited federal grant funding to support PBPK modeling research in academia deters sustainable growth of this field. Some software companies also offer training to allow users to become familiarized with their products (eg, GastroPlus, Simcyp, MATLAB). The Biological Modeling Specialty Section (BMSS) of the Society of Toxicology has also offered webinars over the past few years, especially in regards to the many platforms available for PBPK modeling. In addition to training, harmonized templates for model submission and review could provide a standardized process for model review, thus reducing burden on reviewers, and in turn, increasing the likelihood of model adoption at public health agencies. Some suggested considerations to be included in these templates are presented in further detail below.

It is imperative that when submitting a model for review, the modelers clearly identify the scope of the model, the domain for which the model has been calibrated, the type of assessment supported by the model (eg, route extrapolation or species extrapolation), and sensitivity of model parameters in order to allow reviewers to evaluate the appropriateness of model structure, parameterization, and applications (Clewell and Clewell, 2008; US FDA, 2016). In addition, a summary of basic model characteristics should be provided to describe the species, chemical, age/life stage, exposure scenarios, and target organs. A graphic conceptual schematic of the model design is helpful for visually depicting model compartments, routes of administration/exposure and excretion, and chemical transport and transformation that occur within the biological organism. Additionally, annotation within the code and related datasets (eg, values and sources of model parameters) should indicate how different parameter sets correspond to their respective simulated scenarios (eg, routes, species). Ultimately, the submission documentation should contain sufficient information to allow reviewers and risk assessors to understand model assumptions, independently reproduce simulations, and evaluate the quality of the analysis and validity of the resulting conclusions (Loizou et al., 2008).

Model code or model equations should be provided in order to increase transparency and ensure that independent reproduction of simulations is possible (Peng, 2009, 2011). Reproducibility is a common challenge in PBPK modeling and other computational scientific endeavors (Peng, 2009, 2011), since a study report/manuscript rarely includes all mathematical equations or details sufficient to recreate those equations. Increased attention to model quality and documentation would significantly enhance the ability of students, reviewers, and users to understand how the model was developed, refined, and applied to reach specific conclusions (Clark et al., 2004). Furthermore, careful documentation and quality control will also render the model more apt to be repurposed for other applications and by other users.

KEY ISSUE 2: LACK OF CONFIDENCE IN MODEL EXTRAPOLATION

PBPK modeling has been recognized as a scientifically sound tool for replacing default extrapolation factors (3.16× for interspecies pharmacokinetic uncertainty and 3.16× for intraspecies pharmacokinetic uncertainty (US EPA, 2014) that are commonly applied in the derivation of reference values (Martin et al., 2013; Poet et al., 2016; Thompson et al., 2008; US EPA, 2006; Valcke and Krishnan, 2014). When little or no human in vivo data are available to evaluate the concordance between model predictions and observed data, risk assessors are faced with the challenge of defending their use of human PBPK models developed using in vivo and in vitroanimal data, and sometimes, in vitro human data (Bois et al., 2017; DeWoskin et al., 2013; El-Masri et al., 2016).

This challenge can be illustrated using a recent example in which the FDA evaluated bisphenol A (BPA) toxicity using PBPK modeling (https://www.fda.gov/downloads/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/UCM424266.pdf; last accessed August 16, 2017). Several PBPK models available for BPA were developed based on pharmacokinetic studies carried out with rats and nonhuman primates (Fisher et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2013, 2015; Yang and Fisher, 2015). These animal models were then scaled to humans to predict time profiles for unconjugated BPA (the biologically active form), without the benefit of human data (Edginton and Ritter, 2009; Fisher et al., 2011; Mielke and Gundert-Remy, 2009; Teeguarden et al., 2005). However, these human models were later found to overestimate Cmax and slightly underestimate systemic clearance of BPA serum concentrations measured in humans, and modest recalibration of the models was required to fit the human data (Figure 9 in Yang et al. 2015).

To investigate further the common nature of this challenge, published human models were extracted from a PBPK knowledgebase that contains publications for approximately 300 PBPK models (Lu et al., 2016) for review. Using the query terms: [“human” AND “rat” OR “mouse” OR “dog” OR “monkey” OR “rabbit” OR “guinea pig” OR “sheep” OR “pig” OR “cow” OR “hamster” OR “horse”] returned 145 publications. In total 15 of the 145 articles were excluded because they did not contain human models, with 5 of them referenced future development of a human model and 10 referenced previously published human models.

The remaining 130 publications that contained both animal and human models were reviewed by the authors and further divided into the following 3 groups: (1) articles in which no human in vivo time-concentration or time-response data was available for comparing to model predictions (n = 40); (2) articles in which human in vivotime-concentration or time-response data are used to calibrate human models (n = 46); and (3) articles in which model predictions agreed with available human in vivotime-concentration or time-response data, thus requiring no additional calibration of human models (n = 44).

The studies in group 1 represent primarily academic exercises that applied human PBPK models to understand the pharmacokinetic behavior of a chemical (Crowell et al., 2011; Shin et al., 2011; Teeguarden et al., 2008). In those papers where human time-concentration or time-response data were available (groups 2 and 3), similar numbers of publications were found between those required human data for optimizing parameters to align predictions more closely with observations (group 2) and those simply used human data to demonstrate concordance between model predictions and data without further adjustment to model parameters (group 3). Our review of the articles in groups 2 and 3 revealed that when a model structure relies more on empirical data (group 2), additional fitting of model parameters is often required when conducting animal-to-human extrapolation.

Most published studies in group 2 used a “top-down” modeling approach, in which various biochemical processes were lumped to present the simplest model structure that was capable of reproducing available time-concentration data (Hudachek and Gustafson, 2013; Poet et al., 2004; Sterner et al., 2013). For example, adjusting 1 clearance rate may be sufficient to fit model predictions to rat plasma concentration data. Such an approach is common when the purpose of a study is to organize mechanistic data and present the current state of knowledge regarding the pharmacokinetic behaviors of a chemical. The simplicity of the model structure may negate the need to conduct additional studies to characterize PK processes, but it often requires recalibration of a human model when human data are available, as differences in some physiological or biochemical processes between species cannot be captured by a single parameter (eg, metabolism rate or absorption rate).

In contrast, many published studies in group 3 developed human PBPK models through a “bottom-up” approach (Loccisano et al., 2011; Xia et al., 2012; Watanabe et al., 2009). The model structure for such an approach is based more on a mechanistic understanding of PK processes, and values of model parameters are often derived from in vitro or in silico methods, as opposed to calibrated using in vivo data. Mechanistic-based model parameters, such as tissue-specific expression levels of enzymes or multi-compartmental absorption rates, allow for incorporating intraspecies variability into the model. In some cases, Monte Carlo analysis has been used to quantify the impacts of intraspecies variability on model outputs by providing a distribution of model outputs rather than point estimates (Bois and Brochot, 2016; Gentry et al., 2017b; Strikwold et al., 2017; Worley et al., 2017). Also, simple allometric scaling from animals to humans was shown in several studies in group 3 to be adequate to construct a human version of the PBPK model without further adjustment of parameters, especially for volatile organic compounds (Pelekis and Emond, 2009; Reitz et al., 1996).

Over time, the risk assessment paradigm has shifted away from use of traditional whole animal toxicity testing due to advancements in molecular biology, toxicology, and computing. As a result, the scientific community has developed in vitro and in silico methods that are more efficient and effective, and less expensive, for assessing human health risks posed by exposure to environmental chemicals (Krewski et al., 2010). In light of this shifting paradigm, the PBPK modeling community is also reassessing traditional modeling approaches that are based on in vivo animal data, and starting to explore the use of in vitro and in silico technologies capable of more efficiently generating PBPK models. By no means does this require a complete reinventing of modeling approaches, as in vivo data are still essential for evaluating the predictive capability of a PBPK model. The sophistication of PBPK models will continue to increase with incorporation of, and integration with, emerging data such as omics, protein transporters, and pharmacodynamic models (Abaci and Shuler, 2015; Andersen et al., 2017; Hamon et al., 2014; Kuepfer et al., 2016). These advancements, at the same time, create additional challenges for decision-makers attempting to apply these models in risk assessment, especially when evaluating models in the absence of in vivo data.

KEY ISSUE 3: LACK OF TRANSFERABILITY ACROSS MODELING PLATFORMS

The choice of computing platforms for PBPK modelers is primarily based on the preference or familiarity of model developers. The growing number of platform choices for coding PBPK models (Kuepfer et al., 2016; Poggesi et al., 2014) is an obstacle that hinders the review of models for public health applications, as reviewers require knowledge of both the model and the software used to develop the model. Another issue the PBPK modeling community has routinely faced is that models coded in legacy software platforms may need to be recoded in a different program or may not be accessible. The BMSS webinars have attempted to address this issue by providing training for translating model code across legacy and emerging platforms. In recent years, several research groups have developed open-source packages (eg, HTTK [https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/httk/index.html; last accessed December 2, 2017], MERLIN-Expo [http://merlin-expo.eu/; last accessed December 2, 2017], RVis [http://cefic-lri.org/projects/aimt7-rvis-open-access-pbpk-modelling-platform/; last accessed December 2, 2017], and PLETHEM [http://www.scitovation.com/plethem.html; last accessed December 2, 2017]), and each is designed for a specific purpose, such as postmodeling processing (eg, sensitivity analysis) or generating high throughput in silico predictions. A library that summarizes various platforms and their functionalities would be useful for informing modelers and decision-makers which platform options are best suited for PBPK modeling projects with specific applications. Additionally, generic and consistent data exchange conventions can allow a model developed on 1 platform to be exported and run on a different platform that is familiar to the reviewers. The use of such a data exchange format, such as extensible markup language (XML), coupled with formal ontologies can further improve model documentation, verification, and translation (McLanahan et al., 2012).

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

To protect and promote public health, there is a growing interest among public health agencies in incorporating computational tools, such as PBPK modeling, into research and activities involved in the evaluation of chemical safety. The path forward to advance methods relevant for regulation of chemicals is a 2-way street, requiring input and guidance from regulators as well as PBPK model practitioners. There are demonstrated barriers to the acceptance of PBPK modeling in support of public health decision-making. Although the current review focuses on examples within the United States, the barriers discussed herein are pertinent to modelers and risk assessors in other countries. For example, a survey completed by 93 individuals from 19 countries raises similar concerns, including: (1) lack of expertise in PBPK modeling and applications in public health agencies; (2) lack of data for model validation; (3) lack of user friendly software for non-programmers; and (4) difference in acceptance criteria between agencies and countries (Paini et al., 2017). Some barriers are inherent to the development or application of PBPK models, and some are perceived by risk assessors who are not familiar with PBPK modeling. Recommendations to improve training for both model developers and reviewers, as well as to develop templates to facilitate submission and review of PBPK models, offer hope for addressing these various challenges. A model submission template that requests elucidation of model scope and purposes could also encourage data collectors and modelers to engage risk assessors during the early stage of model development to ensure that the final model is designed to meet the specific needs of those risk assessors. Such engagement should also improve communication by making model results and interpretation more understandable for risk assessors.

There is ongoing discussion and collaboration amongst the computational modeling community regarding incorporation of increasingly sophisticated techniques for improved model parameterization and extrapolation that does not rely on in vivodata. For example, coupling in vitro metabolism data with enzyme ontogeny data can be used to estimate age-dependent in vivo clearance rates. These new techniques, combined with more frequent and open communication of the model development process, pave the way for incorporating models with varying degrees of sophistication in different risk assessment applications, such as screening chemicals for further testing or estimating data-derived extrapolation factors. With explicit documentation detailing the caveats of these different tiers of models, risk assessors can determine the most appropriate application of these models, without having to wait decades for an extensively characterized model suited to 1 specific risk assessment purpose. As more applications are being accepted to support risk assessment, PBPK modeling is likely to be applied more frequently as a quantitative tool to characterize the impact of PK on dose-response assessment. Furthermore, closer interactions between modelers and risk assessors will facilitate prioritization of future model development based on the capacity of existing models to address the needs of regulatory and nonregulatory assessment of risks posed by environmental chemicals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the internal reviewers at the EPA, FDA, and ATSDR for their critical review and comments on a draft of this article.

FUNDING

Funding for Dr Leonard was provided by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education Research Participation Program at the U.S. EPA.

REFERENCES

- Abaci HE, and Shuler ML (2015). Human-on-a-chip design strategies and principles for physiologically based pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics modeling. Integr. Biol 7, 383–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). (2016). Public Health Assessment for Corpus Christi Refineries (Site Wide Activities), Corpus Christi, Nueces County, Texas: Draft for Public Comment; August 29, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen ME, Black MB, Campbell JL, Pendse SN, Clewell III HJ, Pottenger LH, Bus JS, Dodd DE, Kemp DC, and McMullen PD (2017). Combining transcriptomics and PBPK modeling indicates a primary role of hypoxia and altered circadian signaling in dichloromethane carcinogenicity in mouse lung and liver. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 332, 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen ME, Clewell HJ III, Gargas ML, Smith FA, and Reitz RH (1987). Physiologically based pharmacokinetics and the risk assessment process for methylene chloride. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 87, 185–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachler G, von Goetz N, and Hungerbu¨ hler K (2013). A physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for ionic silver and silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed 8, 3365–3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton HA, Chiu WA, Setzer WR, Andersen ME, Bailer AJ, Bois FY, DeWoskin RS, Hays S, Johanson G, Jones N, et al. (2007). Characterizing uncertainty and variability in physiologically based pharmacokinetic models: State of the science and needs for research and implementation. Toxicol. Sci 99, 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudouin R, Micallef S, and Brochot C (2010). A stochastic whole-body physiologically based pharmacokinetic model to assess the impact of inter-individual variability on tissue dosimetry over the human lifespan. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 57, 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bois FY, and Brochot C (2016). Modeling pharmacokinetics Methods Mol. Biol Clifton NJ: 1425, 37–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bois FY, Jamei M, and Clewell HJ (2010). PBPK modelling of inter-individual variability in the pharmacokinetics of environmental chemicals. Toxicology 278, 256–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bois FY, Ochoa JGD, Gajewska M, Kovarich S, Mauch K, Paini A, Pery A, Benito JVS, Teng S, and Worth A (2017). Multiscale modelling approaches for assessing cosmetic ingredients safety. Toxicology 392, 130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, Phillips M, Grulke C, Yoon M, Young B, McDougall R, Leonard J, Lu J, Lefew W, and Tan Y-M (2015). Reconstructing exposures from biomarkers using exposure-pharmacokinetic modeling – A case study with carbaryl. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 73, 689–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu WA, Barton HA, DeWoskin RS, Schlosser P, Thompson CM, Sonawane B, Lipscomb JC, and Krishnan K (2007). Evaluation of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models for use in risk assessment. J. Appl. Toxicol 27, 218–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu WA, and Ginsberg GL (2011). Development and evaluation of a harmonized physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model for perchloroethylene toxicokinetics in mice, rats, and humans. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 253, 203–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu WA, Okino MS, and Evans MV (2009). Characterizing uncertainty and population variability in the toxicokinetics of trichloroethylene and metabolites in mice, rats, and humans using an updated database, physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model, and Bayesian approach. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 241, 36–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claassen K, Thelen K, Coboeken K, Gaub T, Lippert J, Allegaert K, and Willmann S (2015). Development of a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model for preterm neonates: Evaluation with in vivo data. Curr. Pharm. Des 21, 5688–5698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LH, Woodrow Setzer R, and Barton HA (2004). Framework for evaluation of physiologically-based pharmacokinetic models for use in safety or risk assessment. Risk Anal 24, 1697–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clewell RA, and Clewell HJ (2008). Development and specification of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models for use in risk assessment. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 50, 129–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell SR, Henderson WM, Kenneke JF, and Fisher JW (2011). Development and application of a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for triadimefon and its metabolite triadimenol in rats and humans. Toxicol. Lett 205, 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWoskin RS, Sweeney LM, Teeguarden JG, Sams R, and Vandenberg J (2013). Comparison of PBTK model and biomarker based estimates of the internal dosimetry of acrylamide. Food Chem. Toxicol 58, 506–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edginton AN, and Ritter L (2009). Predicting plasma concentrations of bisphenol A in children younger than 2 years of age after typical feeding schedules, using a physiologically based toxicokinetic model. Environ. Health Perspect 117, 645–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Masri H, Kleinstreuer N, Hines RN, Adams L, Tal T, Isaacs K, Wetmore BA, and Tan Y-M (2016). Integration of life-stage physiologically based pharmacokinetic models with Adverse Outcome Pathways and environmental exposure models to screen for environmental hazards. Toxicol. Sci 152, 230–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register (FR). (2014). Peer review of the draft health effects documents for perfluorooctanoic acidand perfluorooctane sulfonate— Interim list of potential peer reviewers. Vol. 79, No. 83 EPA–HQ–OW–2014–0138; FRL–9910–21– OW. Availabl at: https://www.regulations.gov/document?D¼EPA-HQ-OW-2014-0138-0012. Accessed July 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register (FR). (2016a). Drinking water: Perchlorate supplemental request for comments Environmental Protection Agency. Vol. 81, No. 40 EPA–HQ–OW–2009–0297; FRL–8943–9. Available at: https://www.regulations.gov/document?D¼EPA-HQ-OW-2009-0297-0001. Accessed July 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register (FR). (2016b). Request for public comments to be sent to EPA on peer review materials to inform the Safe Drinking Water Act decision making on perchlorate. Vol. 81, No. 190 EPA–HQ–OW–2016–0438; FRL–9953–44– OW. Available at: https://www.regulations.gov/document?D¼EPA-HQ-OW-2016-0438-0001. Accessed July 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register (FR). (2016c). Request for nominations of experts to augment the Science Advisory Board Chemical Assessment Advisory Committee for the review of the EPA’s draft toxicological review of hexahydro-1, 3, 5-trinitro-1, 3, 5- triazine (RDX). Vol. 81, No. 53 FRL–9943–95–OA. Available at: https://www.regulations.gov/document?D¼EPA_FRDOC_0001-18850. Accessed July 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register (FR). (2016d). Request for nominations of experts to augment the Science Advisory Board Chemical Assessment Advisory Committee for the review of EPA draft toxicological reviews for tert-butyl alcohol (tert-butanol) and ethyl tertiary butyl ether (ETBE). Vol. 81, No. 208 FRL–9954– 54–OA. Available at: https://www.regulations.gov/document?D¼EPA_FRDOC_0001-19913. Accessed July 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register (FR). (2017). Trichloroethylene (TCE); Regulation of use in vapor degreasing under TSCA section 6(a). Vol. 82, No. 12 EPA–HQ–OPPT–2016–0387; FRL–9950–08. Available at: 2017. https://www.regulations.gov/document?D¼EPA-HQOPPT-2016-0387-0001. Accessed July 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fierens T, Van Holderbeke M, Standaert A, Cornelis C, Brochot C, Ciffroy P, Johansson E, and Bierkens J (2016). Multimedia & PBPK modelling with MERLIN-Expo versus biomonitoring for assessing Pb exposure of pre-school children in a residential setting. Sci. Total Environ 568, 785–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JW, Twaddle NC, Vanlandingham M, and Doerge DR (2011). Pharmacokinetic modeling: Prediction and evaluation of route dependent dosimetry of bisphenol A in monkeys with extrapolation to humans. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 257, 122–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry PR, Van Landingham C, Fuller WG, Sulsky SI, Greene TB, Clewell HJ, Andersen ME, Roels HA, Taylor MD, and Keene AM (2017a). A tissue dose-based comparative exposure assessment of manganese using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling—The importance of homeostatic control for an essential metal. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 322, 27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry R, Franzen A, Van Landingham C, Greene T, and Plotzke K (2017b). A global human health risk assessment for octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (D4). Toxicol. Lett 279(Suppl 1), 23–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon J, Jennings P, and Bois FY (2014). Systems biology modeling of omics data: Effect of cyclosporine a on the Nrf2 pathway in human renal cells. BMC Syst. Biol 8, 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S-M, Abernethy DR, Wang Y, Zhao P, and Zineh I (2013). The Utility of modeling and simulation in drug development and regulatory review. J. Pharm. Sci 102, 2912–2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudachek SF, and Gustafson DL (2013). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model of lapatinib developed in mice and scaled to humans. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn 40, 157–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones H, Chen Y, Gibson C, Heimbach T, Parrott N, Peters S, Snoeys J, Upreti V, Zheng M, and Hall S (2015). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling in drug discovery and development: A pharmaceutical industry perspective. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 97, 247–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon EM, Eklund C, Leavens T, and Pegram RA (2016). Development and application of a human PBPK model for bromodichloromethane to investigate the impacts of multiroute exposure: Human multi-route BDCM PBPK model. J. Appl. Toxicol 36, 1095–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewski D, Acosta D, Andersen M, Anderson H, Bailar JC, Boekelheide K, Brent R, Charnley G, Cheung VG, and Green S (2010). Toxicity testing in the 21st century: A vision and a strategy. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev 13, 51–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuepfer L, Niederalt C, Wendl T, Schlender J-F, Willmann S, Lippert J, Block M, Eissing T, and Teutonico D (2016). Applied Concepts in PBPK Modeling: How to build a PBPK/PD model. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol 5, 516–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard JA, Tan Y-M, Gilbert M, Isaacs K, and El-Masri H (2016). Estimating margin of exposure to thyroid peroxidase inhibitors using high-throughput in vitro data, highthroughput exposure modeling, and physiologically based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling. Toxicol. Sci 151, 57–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong R, Vieira MLT, Zhao P, Mulugeta Y, Lee CS, Huang S-M, and Burckart GJ (2012). Regulatory experience with physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling for pediatric drug trials. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 91, 926–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loccisano AE, Campbell JL, Andersen ME, and Clewell HJ (2011). Evaluation and prediction of pharmacokinetics of PFOA and PFOS in the monkey and human using a PBPK model. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 59, 157–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loizou G, Spendiff M, Barton HA, Bessems J, Bois FY, d’ Yvoire MB, Buist H, Clewell HJ, Meek B, Gundert-Remy U, et al. (2008). Development of good modelling practice for physiologically based pharmacokinetic models for use in risk assessment: The first steps. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 50, 400–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Goldsmith M-R, Grulke CM, Chang DT, Brooks RD, Leonard JA, Phillips MB, Hypes ED, Fair MJ, TorneroVelez R, et al. (2016). Developing a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model knowledgebase in support of provisional model construction. PLOS Comput. Biol 12, e1004495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin OV, Martin S, and Kortenkamp A (2013). Dispelling urban myths about default uncertainty factors in chemical risk assessment – Sufficient protection against mixture effects? Environ. Health 12, 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan ED, El-Masri HA, Sweeney LM, Kopylev LY, Clewell HJ, Wambaugh JF, and Schlosser PM (2012). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model use in risk assessment–Why being published is not enough. Toxicol. Sci 126, 5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally K, Cotton R, Cocker J, Jones K, Bartels M, Rick D, Price P, and Loizou G (2012). Reconstruction of exposure to m -xylene from human biomonitoring data using pbpk modelling, bayesian inference, and Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation. J. Toxicol 2012, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke H, and Gundert-Remy U (2009). Bisphenol A levels in blood depend on age and exposure. Toxicol. Lett 190, 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumtaz M, Fisher J, Blount B, and Ruiz P (2012). Application of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models in chemical risk assessment. J. Toxicol 2012, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paini A, Leonard JA, Kliment T, Tan Y-M, and Worth A (2017). Investigating the state of physiologically based kinetic modeling practices and challenges associated with gaining regulatory acceptance of model applications. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 90, 104–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelekis M, and Emond C (2009). Physiological modeling and derivation of the rat to human toxicokinetic uncertainty factor for the carbamate pesticide aldicarb. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol 28, 179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng RD (2009). Reproducible research and biostatistics. Biostatistics 10, 405–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng RD (2011). Reproducible research in computational science. Science 334, 1226–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poet TS, Kousba AA, Dennison SL, and Timchalk C (2004). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model for the organophosphorus pesticide diazinon. Neurotoxicology 25, 1013–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poet TS, Schlosser PM, Rodriguez CE, Parod RJ, Rodwell DE, and Kirman CR (2016). Using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling and benchmark dose methods to derive an occupational exposure limit for N-methylpyrrolidone. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 76, 102–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggesi I, Snoeys J, and Van Peer A (2014). The successes and failures of physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling: There is room for improvement. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol 10, 631–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz RH, Gargas ML, Andersen ME, Provan WM, and Green TL (1996). Predicting cancer risk from vinyl chloride exposure with a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 137, 253–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz P, Ray M, Fisher J, and Mumtaz M (2011). Development of a human physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) toolkit for environmental pollutants. Int. J. Mol. Sci 12, 7469–7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankaran H, Adeshina F, and Teeguarden JG (2013). Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model for Fentanyl in support of the development of Provisional Advisory Levels. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 273, 464–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin BS, Bulitta JB, Balthasar JP, Kim M, Choi Y, and Yoo SD (2011). Prediction of human pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of apicidin, a potent histone deacetylase inhibitor, by physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol 68, 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner TR, Ruark CD, Covington TR, Yu KO, and Gearhart JM (2013). A physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for the oxime TMB-4: Simulation of rodent and human data. Arch. Toxicol 87, 661–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strikwold M, Spenkelink B, Woutersen RA, Rietjens IMCM, and Punt A (2017). Development of a combined in vitro physiologically based kinetic (PBK) and Monte Carlo modelling approach to predict interindividual human variation in phenol-induced developmental toxicity. Toxicol. Sci 157, 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeguarden JG, Bogdanffy MS, Covington TR, Tan C, and Jarabek AM (2008). A PBPK model for evaluating the impact of aldehyde dehydrogenase polymorphisms on comparative rat and human nasal tissue acetaldehyde dosimetry. Inhal. Toxicol 20, 375–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeguarden JG, Waechter JM, Clewell HJ, Covington TR, and Barton HA (2005). Evaluation of oral and intravenous route pharmacokinetics, plasma protein binding, and uterine tissue dose metrics of bisphenol A: A physiologically based pharmacokinetic approach. Toxicol. Sci 85, 823–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CM, Sonawane B, Barton HA, DeWoskin RS, Lipscomb JC, Schlosser P, Chiu WA, and Krishnan K (2008). Approaches for applications of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models in risk assessment. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B 11, 519–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US EPA. (2006). Approaches for the application of physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models and supporting data in risk assessment (Final Report). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C. EPA/600/R-05/043F. Available at: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/risk/recordisplay.cfm?deid¼157668. Accessed July 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA. (2014). Guidance for applying quantitative data to develop data-derived extrapolation factors for interspecies and intraspecies extrapolation U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C. Office of the Science Advisor; EPA/ R-14/002F. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-01/documents/ddef-final.pdf Accessed December 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- US FDA. (2016). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic analyses—Format and content guidance for industry U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C. U.S., Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM531207.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Valcke M, and Krishnan K (2014). Characterization of the human kinetic adjustment factor for the health risk assessment of environmental contaminants. J. Appl. Toxicol 34, 227–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verner M-A, Loccisano AE, Morken N-H, Yoon M, Wu H, McDougall R, Maisonet M, Marcus M, Kishi R, Miyashita C, et al. (2015). Associations of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) with lower birth weight: An evaluation of potential confounding by glomerular filtration rate using a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model (PBPK). Environ. Health Perspect 123, 1317–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Kusuhara H, Maeda K, Shitara Y, and Sugiyama Y (2009). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling to predict transporter-mediated clearance and distribution of pravastatin in humans. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 328, 652–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weijs L, Covaci A, Yang RSH, Das K, and Blust R (2012). Computational toxicology: Physiologically based pharmacokinetic models (PBPK) for lifetime exposure and bioaccumulation of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in marine mammals. Environ. Pollut 163, 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2010). Characterization and application of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models in risk assessment. International Programme on Chemical Safety. Harmonization Project Document No. 9. Available at: http://www.inchem.org/documents/harmproj/harmproj/harmproj9.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Worley RR, Yang X, and Fisher J (2017). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of human exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid suggests historical non drinking-water exposures are important for predicting current serum concentrations. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 330, 9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia B, Heimbach T, Lin T, He H, Wang Y, and Tan E (2012). Novel physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of patupilone for human pharmacokinetic predictions. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol 69, 1567–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Doerge DR, and Fisher JW (2013). Prediction and evaluation of route dependent dosimetry of BPA in rats at different life stages using a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 270, 45–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Doerge DR, Teeguarden JG, and Fisher JW (2015). Development of a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for assessment of human exposure to bisphenol A. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 289, 442–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, and Fisher JW (2015). Unraveling bisphenol A pharmacokinetics using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling. Front. Pharmacol. 5, doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokley K, Tran HT, Pekari K, Rappaport S, Riihimaki V, Rothman N, Waidyanatha S, and Schlosser PM (2006). Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modeling of benzene in humans: A Bayesian approach. Risk Anal 26, 925–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon M, and Clewell HJ (2016). Addressing early life sensitivity using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling and in vitro to in vivo extrapolation. Toxicol. Res 32, 15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Zhang L, Grillo JA, Liu Q, Bullock JM, Moon YJ, Song P, Brar SS, Madabushi R, Wu TC, et al. (2011). Applications of physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling and simulation during regulatory review. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 89, 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]