Abstract

Study Objectives:

While short and poor quality sleep among training physicians has long been recognized as problematic, the longitudinal relationships among sleep, work hours, mood, and work performance are not well understood. Here, we prospectively characterize the risk of depression and medical errors based on preinternship sleep disturbance, internship-related sleep duration, and duty hours.

Methods:

Survey data from 1215 nondepressed interns were collected at preinternship baseline, then 3 and 6 months into internship. We examined how preinternship sleep quality and internship sleep and work hours affected risk of depression at 3 months, per the Patient Health Questionnaire 9. We then examined the impact of sleep loss and work hours on depression persistence from 3 to 6 months. Finally, we compared self-reported errors among interns based on nightly sleep duration (≤6 hr vs. >6 hr), weekly work hours (<70 hr vs. ≥70 hr), and depression (non- vs. acutely vs. chronically depressed).

Results:

Poorly sleeping trainees obtained less sleep and were at elevated risk of depression in the first months of internship. Short sleep (≤6 hr nightly) during internship mediated the relationship between sleep disturbance and depression risk, and sleep loss led to a chronic course for depression. Depression rates were highest among interns with both sleep disturbance and short sleep. Elevated medical error rates were reported by physicians sleeping ≤6 hr per night, working ≥ 70 weekly hours, and who were acutely or chronically depressed.

Conclusions:

Sleep disturbance and internship-enforced short sleep increase risk of depression development and chronicity and medical errors. Interventions targeting sleep problems prior to and during residency hold promise for curbing depression rates and improving patient care.

Keywords: depression, internship, medical errors, sleep deprivation, sleep disturbance.

Statement of Significance

Short sleep and depression are endemic to first-year medical residents and represent critical threats to patient safety. In our study, poorly sleeping training physicians were at elevated risk of short sleep and depression development in the first months of residency. The highest rates of depression were observed among physicians with poor quality sleep of short duration (≤6 hr nightly). Further, sleep loss among depressed interns led to a chronic course for depression, whereas increased sleep duration presaged remission of depressive symptoms. Critically, medical error rates were highest among sleep-deprived, overworked, and depressed physicians. Given the roles of sleep disturbance and short sleep on intern depression and performance, detection of sleep problems and early intervention may improve resident mental health and improve patient care.

INTRODUCTION

Medical internship, the first year of residency, is a demanding transition marked by long work hours and sleep loss.1–4 Interns are at significant risk of depression,1,4–6 which is associated with greater self-rated6–8 and reviewer-rated5 medical errors. Depression in this population poses a serious public health problem, and the identification of risk factors for depression and medical errors among interns has the potential to improve public safety.

Sleep disturbances encompass a wide range of complaints, including difficulty falling or staying asleep and poor sleep quality. Sleep disturbance confers a robust risk factor for depression development in the general population,9–13 suggesting that poorly sleeping trainees may be more vulnerable to depression in response to the stressful transition to internship.

Despite limits on work hours, residents still experience high rates of sleep loss.2 Importantly, short sleep duration is associated with resident depression4,14–17 and medical errors.18,19 Concordantly, chronic short nightly sleep of 6 or fewer hours results in neurobehavioral impairment equivalent to one night of complete sleep deprivation.20 Although prior research suggests poor sleep, depression, and performance are related, the effects of sleep problems on depression development and medical errors are poorly understood. Specifically, no study to date on resident health has evaluated the role of preinternship sleep problems in the development of depression during the intern year. Further, it is unclear how changes in sleep duration (losing vs. gaining) during internship influences the course of depression (chronicity vs. remission). Given the depressogenic and neurobehavioral consequences of poor sleep, sleep problems in this population may offer a promising target for prevention or early intervention against depression and physician errors.

Although evidence suggests that multiple dimensions of sleep health uniquely and aggregately impact health and function,21 most prior studies on resident sleep focus on the duration of sleep exclusively. Therefore, very little is known about the influence of sleep disturbance on resident depression. Given recent evidence of the synergistic effects of short sleep and sleep disturbance on depression risk,22,23 psychiatric outcomes may be especially severe in training physicians with sleep disturbance who have short sleep during internship. Estimates of medical errors for depressed, short sleeping, and overworked first-year residents will provide important context for the cost to patient safety posed by these challenges in internship training.

We attempted to address the many outlined gaps in resident sleep, mental health, and function, using the internship year as a naturalistic stressor to examine preinternship sleep disturbance as a risk factor for depression. We hypothesized that poor preinternship sleepers would be at elevated risk of depression and that less sleep during internship would further increase depression risk. We also predicted that sleep loss and long work hours would be associated with depression chronicity from 3 to 6 months. Finally, we examined rates of self-reported medical errors based on short sleep, work hours, and depression status (nondepressed vs. acute vs. chronic). We hypothesized that error rates would be higher among interns who reported short sleep and longer work hours and who screened positive for depression.

METHODS

Participants

The Intern Health Study is a multisite prospective cohort study that aims to assess stress and mood through internship. Trainees were recruited via e-mail with 1342 interns (58% participation rate) in 10 specialties across 33 institutions agreeing to participate in the study (see Table 1 for sample characteristics). As we focused on development of depression during internship, only participants who screened negative for depression at baseline were included (N = 1215, 90.5%). The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent after receiving complete description of the study.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (Nondepressed Subjects Prior to Internship, N = 1215).

| Age | M ± SD: 27.48 ± 2.70 years |

| Sex (female) | N = 591; 48.9% |

| Depression History (positive) | N = 514; 42.3% |

| Race | |

| White | 62.3% |

| Black | 3.6% |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 22.4% |

| Latino | 3.9% |

| Native American | 0.1% |

| Multiracial | 4.3% |

| “Other” | 4.4 % |

| Specialty | |

| Internal medicine | 35.8% |

| Surgery | 11.4% |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 4.5% |

| Pediatrics | 11.4% |

| Psychiatry | 5.9% |

| Emergency medicine | 6.2% |

| Internal medicine/pediatrics | 2.2% |

| Family practice | 5.6% |

| “Other” | 16.0 |

| Transitional | 1.0% |

Note. Depression history reported in response to “To the best of your recollection, have you EVER experienced an episode of depression (a two week period of your life when you felt down or lost interest or pleasure in your usual activities and also had difficulty concentrating or noticed changes in sleep, appetite, energy or experienced thoughts of death or feelings of guilt)?”

Procedure

Data were collected using online surveys, the procedure for which has been outlined in detail elsewhere.6 We examined data from three time points: 1 to 2 months preinternship, 3 months into internship, and 6 months into internship.

Measures

Preinternship Assessment

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index24 (PSQI) was used to assess sleep quality. A global score of greater than 5 indicates significant sleep disturbance and yields good sensitivity (90%) and specificity (87%) in distinguishing good sleepers from poor sleepers.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-925 (PHQ-9) is a 9-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms. As research has shown that inclusion of sleep items on depression scales inflates correlations between depression and sleep measures,26 the PHQ-9 was scored without its sleep item in order to eliminate conflation with the PSQI. Thus, total scores were prorated using mean item-level responses. Proration allowed use of the traditional 10-point cutoff to indicate a positive depression screen. The full PHQ-9 has 93% sensitivity and 88% specificity for detecting clinical depression.27 Acute depression was defined as screening positive for depression at 3-month or 6-month assessment. Chronic depression was defined as screening positive for depression at both 3 and 6 months. In addition to the PSQI and PHQ, demographic information and lifetime depression history were collected preinternship.

Within-Internship Assessments

Interns were assessed at 3 and 6 months into internship. Sleep duration was assessed by asking: “On average, how many hours per day have you slept per night over the past week?” Subjects reporting ≤6 hr of nightly sleep were defined as being short sleepers,20 whereas interns sleeping >6 hr per night were described as longer sleepers. Weekly work hours were estimated in response to: “On average, how many hours have you worked over the past week?” To assess perceived medical errors, interns were asked to answer “Yes” or “No” in response to: “Are you concerned you have made any major medical errors in the last three months?” Depressive symptoms were assessed through the PHQ inventory.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS 20, with a significance threshold of p < .05. We used mediation analysis to test whether preinternship sleep disturbance predicted depression risk at 3 months and whether shorter internship-related sleep duration in the first 3 months of residency mediated this relationship.28,29 Sobel test was used to determine significance of the mediated effect. Because regression coefficients from logistic and linear regression models are on different scales, adjusted parameter estimates accounting for scaling differences between linear and logistic regression were used in the Sobel test and to calculate estimated size of the mediated effect.30 Next, we used dummy-coded logistic regression to compare depression risk across four groups based on self-reported sleep disturbance and duration: (1) longer sleeping good sleepers (reference group); (2) short sleeping good sleepers; (3) longer sleeping poor sleepers; and (4) short sleeping poor sleepers. We then used logistic regression to estimate risk of depression chronicity (i.e., the odds of remaining depressed at 6 months) as predicted by work hours and changes in sleep duration from 3 to 6 months (ΔSleep duration6m−3m). Notably, odds ratios (OR) of negative associations in logistic regression analyses (i.e., OR < 1.0) were inversed to improve interpretability of effect sizes; these are denoted by OR−1in the Results section. Finally, we conducted χ2 tests of independence to compare rates of self-reported medical errors at 3 and 6 months among groups based on sleep duration classification (short vs. longer sleepers), work hours (above and below median), and depression status (nondepressed vs. acute vs. chronic).

RESULTS

Baseline and Internship Sleep

High retention of the 1215 subjects at baseline was observed at 3 months (n = 933, 76.8% retention from baseline) and at 6 months (n = 915, 75.3% retention from baseline). Average nightly sleep duration before internship was 7 hr and 22 min, with 18.3% of the cohort identified as having significant sleep disturbance (PSQI score > 5). Average sleep length at 3 and 6 months into internship were 57 and 56 min shorter in duration, respectively, than preinternship sleep. Nearly half (49.1% and 48.6%) of the sample reported average sleep duration as 6 hr or fewer at 3 and 6 months of internship, reflecting alarming rates of short sleep. Notably, the odds for reporting short sleep were twice as high for preinternship poor sleepers in the first months of internship compared to good preinternship sleepers (60.4% vs. 46.7%; logistic regression: b = −.70, OR−1 = 2.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.39–2.94, p < .001). Interns working 70 hr (the median) or more per week were at fourfolds odds greater risk of being sleep deprived than interns working fewer hours in the first months of internship (logistic regression: b = −1.40, OR−1 = 4.00, 95% CI = 3.03–5.26, p < .001). See Table 2 for full descriptive statistics for sleep, depression, work hours, and medical errors.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Depression Rates, Sleep Parameters, Work Hours, and Perceived Medical Errors.

| Preinternship | 3 Months | 6 Months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | N = 1215 (nondepressed) | N = 933 | N = 915 |

| Depression rates (n, %) | --- | 151, 16.2% | 151, 16.5% |

| PSQI > 5 (n, %) | 222; 18·3% | --- | --- |

| Sleep duration (M ± SD) | 7 hrs 22 mins ± 69 mins | 6 hrs 25 mins ± 57 mins | 6 hrs 28 mins ± 57 mins |

| Short sleep ≤ 6 h (n, %) | 255, 21.0% | 458, 49.1% | 445; 48.6% |

| Work hours (weekly) | --- | 66 hrs 34 mins ± 16 hrs; Median: 70 hrs | 65 hrs 25 mins ± 18 hrs; Median: 70 hrs |

| Perceived medical errors (positive) | --- | n = 165/922; 17.9% | n = 180/900; 20.0% |

Note. Depression rates indicated by Patient Health Questionnaire-9 ≥ 10. Poor sleep indicated by Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index >5. Sleep deprivation ≤6 hr per night on average. Proportion of missing data at the two follow-up assessments was not found to be associated with baseline depression, sleep quality, age, or depression history (all p = NS).

Depression Risk Predicted by Sleep and Work Hours

Positive lifetime depression history (b = .90, OR = 2.46, 95% CI = 1.68–3.61, p < .001) and female sex (b = .53, OR = 1.67, 95% CI = 1.16–2.49, p < .01) but not age (p = NS) predicted depression status at 3 months. Using multiple logistic regression, we compared preinternship good versus poor sleepers in their risk of depression at 3-month assessment while controlling for work hours and significant baseline covariates. The odds of screening positive for depression were twice as high for poor sleepers (OR = 2.33, 95%CI = 1.52–3.57, p < .001; adjusted parameters due to scaling differences for testing mediation: b’ = .18, SE’ = .05). Additionally, longer work hours increased depression risk at 3 months such that each additional hour increased risk by 5% (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.03–1.06, p < .001).

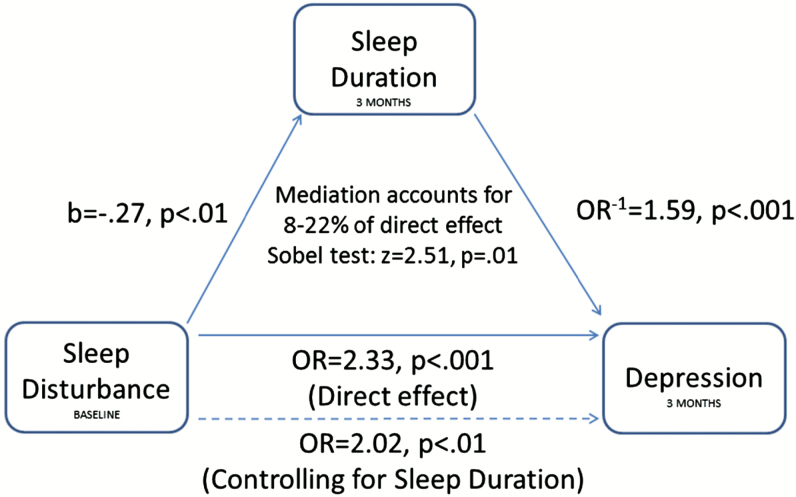

After demonstrating that preinternship sleep disturbance predicts intern depression, we tested whether sleep duration at 3 months mediated this relationship (Figure 1). Preinternship poor sleepers obtained less sleep in the first months of residency than good sleepers (b = −.27, t = −3.31, p < .01; adjusted parameters: b’ = −.06, SE’ = .02). We then estimated depression risk as predicted by sleep duration and found that each hour of less sleep corresponded to a 59% increase in the odds for developing depression (OR−1 = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.27–2.00, p < 001; adjusted parameters: b’ = −.23, SE’ = .05). Notably, sleep disturbance remained a significant predictor of depression after accounting for sleep duration (OR = 2.02, 95% CI = 1.30–3.12, p < .01; adjusted parameters: b’ = .14, SE = .05). Sobel test revealed a significant indirect effect wherein internship sleep duration mediated the relationship between preinternship sleep disturbance and depression development (z = 2.51, p = .01). That is, poorly sleeping physicians were at greater risk of developing depression in the first months of internship, and this relationship was partially due to poor sleepers obtaining less sleep during internship than good sleepers. Estimates of this indirect effect indicated that between 8%1 and 22%2 of preinternship sleep disturbance’s effect on depression development was mediated by internship-imposed short sleep.

Figure 1.

Internship short sleep duration mediating preinternship sleep disturbance and depression development.

After finding that both sleep disturbance and sleep duration were independently associated with depression risk, we tested for compounding effects of poor sleep quality and short sleep. Specifically, sleep quality (PSQI) scores and internship sleep duration at 3 months were used to create four groups, longer sleeping good sleepers, short sleeping good sleepers, longer sleeping poor sleepers, and short sleeping poor sleepers, allowing for comparison of depression rates and risk among the four groups. Chi-square analysis indicated that depression rates significantly differed among these groups (χ2 = 50.52, p < .001). Data presented in Table 3 show that depression rates 3 months into internship were higher in interns with either poor quality sleep (18.5%) or short sleep (21.7%) compared to interns without sleep problems (7.4%). Notably, the highest depression rates were reported by interns with both poor quality and short sleep (32.7%). Dummy-coded logistic regression revealed that all three groups of problematic sleepers were at greater risk of depression than the good sleeping control group, with short sleeping poor sleepers at greatest risk of depression. These results indicate that sleep disturbance and short sleep duration have compounding effects on intern depression (see Table 3 for ORs and ps).

Table 3.

Rates of Depression at 3 Months Among Interns Grouped by Sleep Quality and Sleep Quantity.a

| Depression Status at 3 Months | OR, p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Screen | Positive Screen | % Depressed | ||

| Sleep classification | ||||

| Longer sleeping good sleepers | 376 | 30 | 7.4% | -- |

| Longer sleeping poor sleepers | 53 | 12 | 18.5% | 3.04, <.01 |

| Short sleeping good sleepers | 278 | 77 | 21.7% | 2.34, <.001 |

| Short sleeping poor sleepers | 66 | 32 | 32.7% | 4.24, <.001 |

Note. aControlling for age, gender, and work hours. Good vs poor sleep indicated by Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index >5. Longer sleep >6 hr per night on average at 3 months into internship. Short sleep ≤6 hr per night on average at 3 months into internship. OR = Odds ratio, which was derived from a multiple logistic regression estimating depression status as predicted by dummy coded variables for sleep classification with longer sleeping good sleepers as the reference group.

Depression Chronicity as Predicted by Sleep Loss

We then tested whether changes in sleep duration during internship predicted the course of depression. For interns screening positive for depression at 3-month assessment, we found that losing sleep over the subsequent 3 months corresponded to increased odds for the persistence of depression to a chronic course (ΔSleep duration6m−3m; b = −44, OR−1 = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.01–2.36, p = .04). Each hour of lost sleep corresponded to a 55% increase in odds for remaining depressed. Post hoc χ2 analysis revealed group differences among depressed interns who lost sleep, gained sleep, and reported no change (χ2 = 10.46, p < .01). Specifically, 78.3% (18/23) of depressed interns who lost 30 min or more of nightly sleep remained depressed and 53.5% (23/43) of depressed interns whose sleep length was unchanged remained depressed. By comparison, only 38.6% (22/57) of depressed interns who gained 30 min or more of nightly sleep remained depressed. Work hours at 6 months, age, sex, baseline sleep disturbance, and depression history were not significant predictors of depression chronicity.

Etiological Roles of Sleep Disturbance and Short Sleep in New Onset vs. Relapse of Depression

Due to the high rates of self-reported lifetime depression (42.3%) in our sample and its association with risk of internship depression (OR = 2.46, p < .001, reported earlier), we conducted post hoc analyses to explore whether the etiological roles of sleep disturbance and short sleep in developing depression differed between new onset and relapse, that is, between those without and with a prior history of depression. Overall, the results did not differ between the two groups. Irrespective of whether internship depression was an initial onset or relapse, preinternship sleep disturbance increased risk of depression development (Relapse group: OR = 2.12, p < .001; Onset group: OR = 2.01, p < .001) as did shorter sleep duration during internship (Relapse group: OR−1 = 1.39, p = .02; Onset group: OR−1 = 1.96, p < .001) while controlling for the previously identified covariates. Similarly, a repeat of our dummy-coded logistic regression (with longer sleeping good sleepers as the reference group) showed that short sleeping poor sleepers (i.e., with sleep disturbance and short sleep) were at the greatest risk of internship depression (Relapse group: OR = 4.05, p < .01; Onset group: OR = 5.40, p < .01) to be at greatest risk of depression development. Further, sleep loss from 3 to 6 months predicted greater chronicity in both previously depressed interns (OR−1 = 1.61, p < .01) and interns without depression history (OR−1 = 1.45, p < .01).

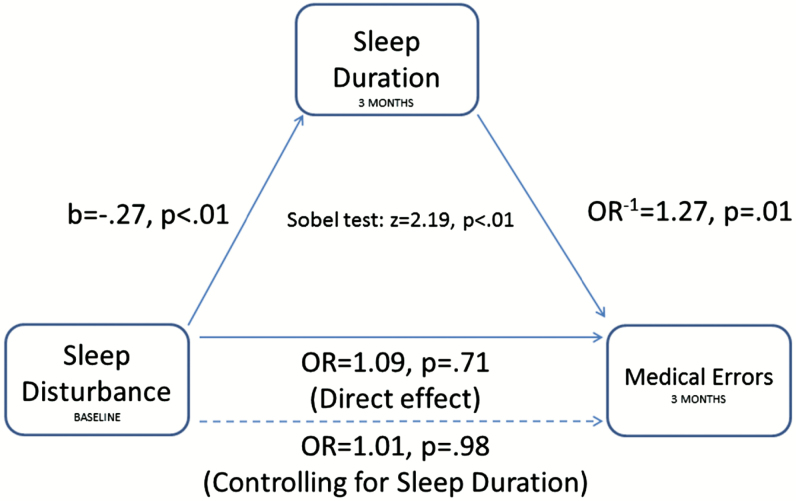

The Influence of Problematic Sleep on Physician Performance

We then examined the effects of sleep disturbance and short sleep on risk of medical errors (Figure 2). As reported earlier, preinternship poor sleepers obtained less sleep in the first months of residency than good sleepers (b = −.27, t = −3.31, p <.01; adjusted parameters: b’ = −.06, SE’ = .01). We then estimated error risk as predicted by sleep duration and found that each hour of less sleep corresponded to a 27% increase in the odds for reporting medical errors (b = −.24, OR−1 = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.27–1.53, p = .01; adjusted parameters: b’ = −.12, SE’ = .05). Sobel test revealed a significant indirect effect wherein poor quality sleepers obtained shorter sleep during internship, which increased risk of committing medical errors (z = 2.19, p < .01).

Figure 2.

Internship short sleep duration mediating preinternship sleep disturbance and risk for medical errors.

Error Rates Associated With Sleep Deprivation, Long Work Hours, and Depression

Finally, rates of perceived medical errors at 3 and 6 months were compared among intern subgroups based on sleep duration, work hours, and depression status (see Table 4 for full results). Error rates at 3 months were significantly higher in short sleeping interns than longer sleepers (χ2 = 4.34, relative risk [RR] = 1.3, p = .03). However, there was no statistically significant difference in errors between short and longer sleepers at the 6-month assessment (χ2 = 2.15, p = .14). Next, we observed error rates to be greater for interns working ≥70 per week at both 3 months (χ2 = 8.74, RR = 1.5, p < .01) and 6 months (χ2 = 6.62, RR = 1.4, p = .01).

Table 4.

Prevalence of Perceived Medical Errors Among Interns Grouped by Depression Status, Sleep Duration, and Work Hours.

| Perceived Medical Errors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Months | 6 Months | |||

| Sleep duration | χ2 = 4.34, p = .03 | χ2 = 2.15, p =. 14 | ||

| Short sleep | 20.6% | 22.0% | ||

| Longer sleep | 15.4% | 18.1% | ||

| Work hours | χ2 = 8.74, p < .01 | χ2 = 6.62, p =. 01 | ||

| Work hours ≥ 70 hr | 22.1% | 23.9% | ||

| Work hours < 70 hr | 14.6% | 17.0% | ||

| Depression | χ2 = 22.79, p < .001 | χ2 = 27.34, p < .001 | ||

| Nondepressed | 13.6% | 15.4% | ||

| Acutely depressed | 26.2% | 25.4% | ||

| Chronically depressed | 32.8% | 41.0% | ||

Note. Interns with short sleep reported ≤6 hr of nightly sleep. Interns with longer sleep reported >6 hrs of nightly sleep. Work hours groups were created using a median split, which was identical at within-internship assessments. Nondepressed = No positive depression status at any time point. Acutely depressed = Positive depression status at either 3- or 6-month follow-up. Chronically depressed = Depressed at both follow-up assessments.

In comparing nondepressed, acutely, and chronically depressed interns on error rates, significant group differences were observed (Table 4). Error rates increased from 14%–15% among nondepressed interns to 25%–26% among acutely depressed interns. Unsurprisingly, chronically depressed interns reported the highest error rates at 33%–41%. Relative risk estimates showed that chronically depressed interns were 1.3 to 1.6 times at greater risk of errors than acutely depressed interns, and 2.4 to 2.7 times at greater risk of errors than nondepressed interns.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that preinternship sleep disturbance and internship-related short sleep (≤6 hr nightly) and long work hours were associated with increased risk of depression development and chronicity as well as perceived medical errors in first-year residents. Although prior studies have examined individual relationships among sleep, work hours, depression, and resident performance, this investigation is the first to demonstrate that training physicians with poor quality sleep prior to internship are at elevated risk for sleep deprivation, developing depression, and committing medical errors in the first months of residency, and that sleep loss across internship leads to a chronic course of depression. We also found that interns with short sleep, longer work hours, and depression were at increased risk of reporting medical errors.

Incoming interns with poor sleep at baseline are at high risk of depression and short sleep in the first months of internship. This finding is consistent with evidence demonstrating sleep disturbance as a risk factor for depression in other populations.9–13,31,32 After transitioning to internship, average nightly sleep decreased by almost an hour, with shorter sleep during internship associated with increased risk of depression. Notably, poor sleepers at baseline obtained less sleep during internship than good sleepers, partially accounting for the relationship between preinternship sleep disturbance and depression development. Importantly, sleep problems had compounding effects such that interns with both sleep disturbance and short sleep had the highest rates of depression, with nearly 33% of these interns meeting criteria for depression at 3 months of internship. Our data also showed that the etiological roles of sleep disturbance and short sleep on depression development did not differ between subjects with or without a prior history of depression. That is, short sleep amplifies the effects of sleep disturbance in depression development whether individuals are experiencing a new onset of depression or a relapse.

Overall, our findings are consistent with research showing residency-related short sleep may be related to depression and daytime impairments.15–17 Our work builds on this literature and demonstrates that sleep issues prior to intern year predispose trainees to work-related short sleep and depression. The importance of obtaining sufficient sleep is reinforced by our finding that sleep loss was associated with a chronic course for depression, while increased sleep predicted greater likelihood of remission. These findings are consistent with research in other populations showing that sleep loss and short sleep duration are associated with depression.33–37 Importantly, Fernandez-Mendoza et al.22 and others23 have shown that insomniacs with unconstrained (i.e., not environmentally truncated) short sleep duration are at greater risk of depression than individuals with poor quality sleep or short sleep alone. Our data expand on these findings by suggesting that environmentally imposed short sleep may similarly amplify the risk relationship between sleep disturbance and depression. Moreover, our results lend further support to the multidimensionality of sleep health, as proposed by Buysse,21 which highlights that various dimensions of sleep–wake function (i.e., satisfaction, duration, efficiency, alertness, and timing) can uniquely and, when combined, aggregately impact health and function.

Physicians having difficulty sleeping prior to internship are at elevated risk of committing medical errors after transitioning to intern year. Notably, however, the elevated error risk for poor sleepers is due to obtaining less sleep during internship. Indeed, medical errors were elevated among interns reporting short sleep, working 70 or more weekly hours and screening positive for depression. Indeed, the lowest rates of errors were reported by interns who were nondepressed, obtained more than 6 hr of nightly sleep, and worked fewer than 70 hr per week. In contrast, nearly one-quarter of interns with acute depression, short sleep, or who worked 70 or more hours per week reported errors. The highest error rates at 31%–40% were reported by chronically depressed interns, which is consistent with past studies examining depression and self-rated6–8 and reviewer-rated5 medical errors in this population. As chronically depressed interns reported high levels of poor sleep quality, short sleep, and long duty hours, these results highlight the impact of sleep problems and long duty hours on intern mental health and work performance.

The present study should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. Although the PHQ has demonstrated excellent diagnostic utility as a screening tool,27 performance characteristics of our modified PHQ have not been empirically evaluated. Clinical interviews are necessary for diagnosis of psychiatric disorders. Further, while subjective sleep ratings are shown to correspond to objective sleep measures,38,39 the gold standard of sleep assessment involves the combination of subjective ratings and objective sleep measures (e.g., actigraphy and polysomnography). Further, internship nightly sleep duration and depression status were assessed at the same time, and hypotheses regarding directionality of sleep duration and depression are based on prior research on sleep issues and psychiatric illness9,10,13 and supported by excluding depressed subjects at baseline. Even so, future investigations may include both continuous subjective and objective sleep measures prior to and across the intern year, which may offer greater insights into the directionality of sleep, mood, and physician performance in this population. Notably, we did not collect sleep quality data during internship. Although we did not observe a direct prospective relationship between preinternship sleep disturbance and intern performance, future investigations should determine whether sleep disturbance during periods of medical practice impairs performance. Further, researchers should consider investigating the prevalence of sleep disorders, such as shift work disorder, among first-year residents, and how rotating shifts and night floats may affect sleep duration, mood, and physician performance. Internship training imposes significant changes in sleep timing and quality, and sleep-deprived residents may try to catch up on sleep during the daytime, which may affect these relationships. Both duty hours and medical errors were self-reported. Importantly, research has shown high agreement between physician reports of adverse events and those indicated in medical records.40 Even so, it is possible that depressed interns are more likely to recall errors due to negative attention biases, and it is important to note that interns working longer hours have more opportunity to commit errors. Moreover, by assessing major medical errors, our study may underestimate actual medical errors with potential to cause patient harm that residents may not have considered to be major. Finally, other factors such as personal medical issues, substance use, and family stress may impact both sleep and mental health outcomes but were not accounted for by this study.

Our findings suggest that promoting good sleep in training physicians may enhance depression prevention efforts and improve patient welfare. Individuals sleeping poorly prior to internship may represent a population to target for prevention and early intervention efforts. Trainees with severe sleep disturbance may suffer from insomnia disorder and may benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia as a first-line treatment41,42 to improve sleep quality prior to the stressful transition to internship. As internship-related short sleep was associated with acute and chronic depression and medical errors, promoting sufficient and quality sleep through the design of shift schedules that account for internal circadian clocks, the maintenance of regular sleep–wake patterns, allowing adequate time in bed, and promoting good sleep hygiene may reduce rates of depression and improve patient care. For depressed interns, treatment planning may benefit from addressing the critical role of poor sleep in depression; therefore, interventions addressing both sleep and depression issues may improve treatment outcomes in this population.

FUNDING

NIMH R01 MH101459 (Sen), NIMH K23 MH095109 (Sen), T32 HL110952 (Pack), and the University of Michigan Taubman Institute Internal Grant (Sen). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Study concept and design: Sen, Guille. Drafting of the manuscript: Kalmbach, Arnedt, Sen. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Kalmbach, Sen, Arnedt, Guille, Song. Statistical Analysis: Kalmbach. Interpretation of data: Kalmbach, Sen, Arnedt, Guille, Song. Administrative, technical, or material support: Sen, Guille. Study supervision: Sen, Guille. Srijan Sen MD PhD (University of Michigan Medical School) was the principal investigator. The authors would like to extend our gratitude to Joan Zhao MS for her immeasurable help managing and preparing the databases for analyses. I would like to send a personal thank you to the late and supremely great Dr. Vivek Pillai without whose guidance this manuscript and many of others of mine would not exist. The field of clinical sleep research has lost an intellectual giant, as I have lost my brother. – DAK. Annual Meeting of Associated Professional Sleep Societies June 6-10 2015. National Network of Depression Centers Annual Conference November 4-6 2015.

ENDNOTES

Calculated by dividing the estimated indirect effect by the total direct effect. Specifically, we divided the product of the adjusted parameter estimates comprising the indirect effect by the adjusted estimate of the direct effect: [(−.06) × (−.23)]/.18.

Calculated by dividing the difference between the total direct effect and direct effect accounting for the mediation by the total direct effect: (.18 − .14)/.18.

REFERENCES

- 1. Collier VU, McCue JD, Markus A, Smith L. Stress in medical residency: status quo after a decade of reform? Ann Intern Med. 2002; 136(5): 384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sen S, Kranzler HR, Didwania AK, et al. Effects of the 2011 duty hour reforms on interns and their patients: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. JAMA internal medicine. 2013;173(8):657–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arora VM, Georgitis E, Woodruff JN, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer D. Improving sleep hygiene of medical interns: can the sleep, alertness, and fatigue education in residency program help? Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167(16): 1738–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosen IM, Gimotty PA, Shea JA, Bellini LM. Evolution of sleep quantity, sleep deprivation, mood disturbances, empathy, and burnout among interns. Acad Med. 2006; 81(1): 82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008; 336(7642): 488–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sen S, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, et al. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010; 67(6): 557–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006; 296(9): 1071–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010; 251(6): 995–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drake CL, Pillai V, Roth T. Stress and sleep reactivity: a prospective investigation of the stress-diathesis model of insomnia. SLEEP. 2013;37(8):1295–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011; 135(1-3): 10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Franzen PL, Buysse DJ. Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008; 10(4): 473–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee E, Cho HJ, Olmstead R, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, Irwin MR. Persistent sleep disturbance: a risk factor for recurrent depression in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep. 2013; 36(11): 1685–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Riemann D, Voderholzer U. Primary insomnia: a risk factor to develop depression? J Affect Disord. 2003; 76(1-3): 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goebert D, Thompson D, Takeshita J, et al. Depressive symptoms in medical students and residents: a multischool study. Acad Med. 2009; 84(2): 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Friedman RC, Kornfeld DS, Bigger TJ. Psychological problems associated with sleep deprivation in interns. J Med Educ. 1973; 48(5): 436–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rose M, Manser T, Ware JC. Effects of call on sleep and mood in internal medicine residents. Behav Sleep Med. 2008; 6(2): 75–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vorona RD, Chen IA, Ware JC. Physicians and sleep deprivation. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 2009;4(4):527–540. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lockley SW, Barger LK, Ayas NT, Rothschild JM, Czeisler CA, Landrigan CP; Harvard Work Hours, Health and Safety Group Effects of health care provider work hours and sleep deprivation on safety and performance. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007; 33(11 Suppl): 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baldwin DC, Jr, Daugherty SR. Sleep deprivation and fatigue in residency training: results of a national survey of first- and second-year residents. Sleep. 2004; 27(2): 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van Dongen HP, Maislin G, Mullington JM, Dinges DF. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2003; 26(2): 117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buysse DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep. 2014; 37(1): 9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fernandez-Mendoza J, Shea S, Vgontzas AN, Calhoun SL, Liao D, Bixler EO. Insomnia and incident depression: role of objective sleep duration and natural history. Journal of sleep research. 2015;24(4):390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kalmbach DA, Pillai V, Arnedt JT, Drake CL. DSM-5 insomnia and short sleep: Comorbidity landscape and racial disparities. SLEEP. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd , Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989; 28(2): 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Group PHQPCS Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Jama. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hartz AJ, Daly JM, Kohatsu ND, Stromquist AM, Jogerst GJ, Kukoyi OA. Risk factors for insomnia in a rural population. Ann Epidemiol. 2007; 17(12): 940–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9. Journal of general internal medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fairchild AJ, MacKinnon DP. A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prev Sci. 2009; 10(2): 87–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mackinnon DP, Fairchild AJ. Current Directions in Mediation Analysis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009; 18(1): 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation review. 1993;17(2):144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perlis ML, Giles DE, Buysse DJ, Tu X, Kupfer DJ. Self-reported sleep disturbance as a prodromal symptom in recurrent depression. J Affect Disord. 1997; 42(2-3): 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kalmbach DA, Pillai V, Cheng P, Arnedt JT, Drake CL. Shift work disorder, depression, and anxiety in the transition to rotating shifts: the role of sleep reactivity. Sleep Med. 2015; 16(12): 1532–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tsuno N, Besset A, Ritchie K. Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005; 66(10): 1254–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dahl RE. The consequences of insufficient sleep for adolescents. Phi Delta Kappan. 1999;80(5):354–359. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaneita Y, Ohida T, Uchiyama M, et al. The relationship between depression and sleep disturbances: a Japanese nationwide general population survey. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kalmbach DA, Arnedt JT, Swanson LM, Rapier JL, Ciesla JA. Reciprocal dynamics between self-rated sleep and symptoms of depression and anxiety in young adult women: A 14-day diary study. Sleep Medicine. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Krueger PM, Friedman EM. Sleep duration in the United States: a cross-sectional population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009; 169(9): 1052–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kushida CA, Chang A, Gadkary C, Guilleminault C, Carrillo O, Dement WC. Comparison of actigraphic, polysomnographic, and subjective assessment of sleep parameters in sleep-disordered patients. Sleep Med. 2001; 2(5): 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, Liu K, Rathouz PJ. Self-reported and measured sleep duration: how similar are they? Epidemiology. 2008; 19(6): 838–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weingart SN, Callanan LD, Ship AN, Aronson MD. A physician-based voluntary reporting system for adverse events and medical errors. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(12): 809–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, Cooke M, Denberg TD. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Riemann D, Nissen C, Palagini L, Otte A, Perlis ML, Spiegelhalder K. The neurobiology, investigation, and treatment of chronic insomnia. Lancet Neurol. 2015; 14(5): 547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]