Abstract

Objectives. To examine the effect of maltreatment during childhood on subsequent financial strain during adulthood and the extent to which this effect is mediated by adolescent depressive symptoms, adolescent substance abuse, attenuated educational achievement, and timing of first birth.

Methods. We specified a multilevel path model to examine the developmental cascade of child maltreatment. We used data from a longitudinal panel study of 496 parents participating in the Rochester Intergenerational Study, in Rochester, New York. Data were collected between 1988 and 2016.

Results. Child maltreatment had both a direct and indirect (via the mediators) effect on greater financial strain during adulthood.

Conclusions. Maltreatment has the capacity to disrupt healthy development during adolescence and early adulthood and puts the affected individual at risk for economic difficulties later in life. Maltreatment is a key social determinant for health and prosperity, and initiatives to prevent maltreatment and provide mental health and social services to victims are critical.

The ecology of an individual’s childhood has the capacity to foster or hinder adaptive development over the life course. This notion is a primary premise of the American Academy of Sciences’ ecobiodevelopmental model,1 a framework designed to elucidate the interplay of childhood ecology (i.e., the environmental and social contexts that the child navigates), biology (including genetics and neurodevelopment), and long-term prosperity in terms of mental, physical, social, and economic well-being. Recently, the ecobiodevelopmental framework has been used to explain the consequences of child maltreatment, a trauma that can lead to toxic stress and ensuing health risk behaviors (e.g., substance abuse, poor eating and exercise habits, risky sexual behaviors), and ultimately poor mental and physical health (e.g., depression and cardiovascular disease).1–3 Indeed, child maltreatment’s ill effect on health outcomes can be far reaching, long lasting, and profound.

While a great deal of work has documented the harmful impacts of maltreatment on health, far less has examined the socioeconomic consequences of child maltreatment. To fill this gap, Metzler et al.4 recently demonstrated that victims of child maltreatment experience worse socioeconomic outcomes in adulthood, including fewer years of education, poorer employment prospects, and lower wages. In this article, our goals were to extend this work in 3 ways: (1) to determine if the harmful effect of maltreatment found by Metzler et al. can be replicated in a prospective, longitudinal study, (2) to control for a broader array of potential confounders, and (3) to identify potential mediators that link childhood maltreatment to financial strain in adulthood.

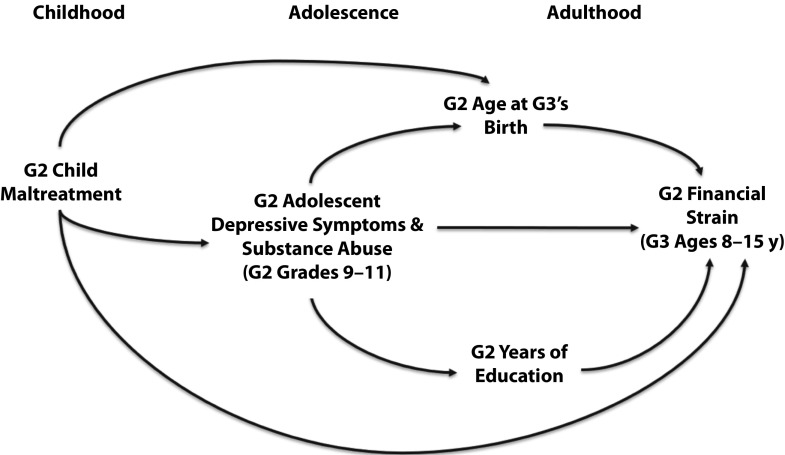

In doing so, we sought to examine the developmental cascade set in motion by child maltreatment. Masten and Cicchetti defined a developmental cascade as “the cumulative consequences for development of the many interactions and transactions occurring in developing systems that result in spreading effects across levels, among domains at the same level, and across different systems or generations.”5(p491) The developmental cascade model that undergirds our longitudinal exploration is presented in Figure 1. Specifically, we examined the extent to which child maltreatment was associated with the following ill outcomes for the victim:

depressive symptoms in adolescence,

substance abuse in adolescence,

poorer educational attainment,

earlier entry into parenthood, and, ultimately,

financial strain during parenthood.

FIGURE 1—

A Developmental Cascade of the Consequences of Child Maltreatment on Adult Socioeconomic Outcomes: Rochester Youth Development Study and Rochester Intergenerational Study, Rochester, NY, 1988–2016

Note. G2 = generation 2; G3 = generation 3.

The first phase of our conceptual model is the proximal effect of child maltreatment on adolescent depressive symptoms and substance abuse, as there is evidence that maltreatment can have a negative impact on both outcomes.6,7 In general, early childhood exposure to toxic environments is related to changes in the brain that may make it more difficult to regulate stress and navigate social and emotional experiences,1 and the ensuing toxic environment produced by a context of maltreatment has the capacity to produce psychopathology among victims.

The second phase of our conceptual model pertains to the role that maltreatment, and ensuing psychopathology in the form of mental health and substance abuse, play in hampering the achievement of the developmental tasks of adolescence and early adulthood.8 We hypothesized that the confluence of these risks would decrease the likelihood that a victim of child maltreatment would accumulate adequate education and increase the likelihood that a victim would become a parent at an earlier age. There is some evidence in the literature that maltreatment, depression, and substance abuse are each predictive of poorer educational attainment,4,9,10 as well as earlier entry into parenthood.11,12

The final phase of our conceptual model describes the transition to adulthood. In the United States, one of the most important markers of a successful transition to adulthood is financial security. Financial security means being free from the severe strain of worrying about having enough food to survive, maintaining a roof overhead, and being able to access basic life necessities.13–15 Unfortunately, there is evidence that such financial security can be compromised when an individual is maltreated as a child. Victims of child maltreatment are more likely to experience poorer socioeconomic outcomes in adulthood,4,16–18 even after control for preexisting socioeconomic differences.17 Moreover, the confluence of compromised development during adolescence marked by depression, substance abuse, and precocious transitions to adulthood is likely to have negative implications for financial security as well.8 The degree to which this type of compromised development might explain the relationship between maltreatment and subsequent socioeconomic circumstances is largely unknown, and longitudinal studies that can model change across time in these critical processes and elucidate important intermediate variables in the cascade are needed.

We tested our developmental cascade model by using data from a longitudinal and intergenerational panel study of 496 ethnically and socioeconomically diverse parents who were initially recruited to participate in a study of adolescent development in 1988 when they were in junior high school, and subsequently recruited to participate in an intergenerational study of families once they became parents. We adjusted for a broad array of variables that may cause an individual to be maltreated and also to suffer from the proposed consequences of maltreatment. These included the socioeconomic situation of the individual during his or her childhood and adolescence, as well as characteristics of the individual’s primary caregiver.

METHODS

We used data from 2 companion longitudinal studies. The original study, the Rochester Youth Development Study (RYDS), began in 1988 and the intergenerational extension, the Rochester Intergenerational Study (RIGS), began in 1999. Detailed information about the methods of these studies is presented in Thornberry et al.19; a summary is provided here.

The RYDS randomly sampled 1000 seventh- and eighth-grade students from Rochester, New York, city schools (referred to as generation 2 [G2]; their primary caregiver is referred to as G1). The RYDS was funded by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention to study the causes and correlates of adolescent crime. As such, adolescents at high risk for problem behaviors were oversampled. This was accomplished by oversampling male adolescents and adolescents living in high-crime areas of the city. Phase 1 of the RYDS took place from 1988 to 1992 and covered G2’s adolescent years. The G2 adolescents were interviewed 9 times at 6-month intervals, and G1 was interviewed at the first 8 interviews. Phase 2 of RYDS took place from 1994 to 1997 and covered G2’s emerging adulthood; G1 and G2 participants were interviewed 3 times at 1-year intervals. Finally, phase 3 of RYDS took place from 2003 to 2006 and covered the late 20s and early 30s; G2 participants were interviewed twice with 2 years between each interview. The project maintained an 80% retention rate through phase 3.

The RIGS selected G2’s oldest biological child (G3) who was aged 2 years or older and added new firstborns as they turned 2 years in each subsequent year. Annual interviews of G2 and G3 have occurred since year 1. The RIGS is ongoing and, at the current time, 539 G2 participants and each one’s firstborn child (G3) have participated in the study.

Measures

Maltreatment of G2 during childhood (before age 12 years) was ascertained via self-report during phase 2 of RYDS, when the parent was aged approximately 23 years. Seven questions inquired about forms of neglect (e.g., left alone), 8 questions inquired about physical abuse (e.g., intentionally injured by a caregiver), and 12 questions inquired about sexual abuse (e.g., being touched in a sexual way by an individual who was aged 15 years or older). Emotional abuse was not ascertained as part of the self-report measurement. Of the 132 individuals who reported abuse, 43 reported multiple forms of abuse. Because of limited space and relatively small sample size, we did not consider the consequences of multiple forms of abuse. Rather, we focused on 4 comparisons for the self-report measures. First, we compared people who reported any type of abuse with those who reported no abuse. Then, for each type of abuse (i.e., neglect, physical, sexual), we compared people who reported that particular type (irrespective of whether they reported additional types as well) with those who reported no abuse. Thus, the reference group for each type of self-reported abuse comprises those G2 participants who reported no neglect, physical abuse, or sexual abuse from ages 0 to 12 years (n = 364).

In addition to this self-report measure, we also considered maltreatment victimization based on data from the Child Protective Services (CPS) records of the Monroe County Department of Social Services, the county of residence for all participants at the start of RYDS. We only had access to substantiated incidents—that is, incidents for which an intake officer found that there was sufficient evidence to consider the case valid. We considered all incidents—from ages 12 through 17 years—in which G2 was the victim of any form of substantiated maltreatment; this included neglect (the failure of caregivers to provide needed and age-appropriate care), physical abuse (acts that actually caused or could cause physical injury to a child), emotional abuse (behavior, typically verbal behavior, that causes or could cause conduct, cognitive, or affective disorders), and sexual abuse (involvement of the child in sexual activities including, but not limited to, direct contact for sexual purposes, molestation, or rape). Given the small sample size and relatively few cases of substantiated maltreatment, we considered only a binary indicator of official report of maltreatment (i.e., any official record vs no official record), and did not differentiate type of maltreatment.

Depressive symptoms (e.g., feeling depressed or very sad, feeling lonely) of G2 in grades 9, 10, and 11 (phase 1 of RYDS) were measured with 11 items derived from the Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).20 All items were measured on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often); the average of the items was taken at each interview, with a higher score indicative of more depressive symptoms. Across the interviews, Cronbach α for the depressive symptoms scale ranged from 0.82 to 0.88. We calculated the maximum score across grades 9, 10, and 11 for use in our analyses.

Substance abuse by G2 in grades 9, 10, and 11 was measured with a series of variables that inquired about alcohol and cannabis use. Using these items, we formed 2 indicators of substance abuse—1 for alcohol and 1 for cannabis—each defined by 4 ordered categories: (0) no use, (1) some use since the date of last interview (approximately 6 months), (2) use in the past 30 days, and (3) experience of 1 or more consequences of use (e.g., forgot where one was or what one did after using, got into trouble with police). We calculated the maximum substance abuse score (for either alcohol or cannabis) across grades 9, 10, and 11 for use in our analyses.

The age of G2 at first birth (expressed in years) was recorded at the time of entry into RIGS and was treated as a continuous variable in the analyses. Accumulated years of education for G2 (expressed in years of completion), was collected at phase 3 of the study (when G2 was in their early 30s) and was also treated as a continuous variable.

Financial strain of G2’s household when G3 was between the ages of 8 and 15 years was measured at the annual RIGS interview. Since their last annual interview, G2 indicated if the household had experienced each of the following:

had to cut the size of meals or skip a meal altogether because the family ran out of money or food stamps,

got behind in the rent or house payments,

did not have enough money to pay utility bills,

had utilities shut off because of nonpayment,

lost financial benefits,

experienced serious financial problems, or

lost a job.

We constructed the sum of these 7 variables at each G3 age for use in the analyses. We treated this variable as a count variable with a negative binomial distribution in our models.

In addition to the key variables of interest, we included a set of relevant potential confounders. These included G2’s sex, race/ethnicity, and age at the start of RYDS. We also included variables that described the participant’s family environment at the start of the study (all reported by G1): G1’s accumulated years of education, low socioeconomic status at the start of RYDS (a binary variable indicating whether the primary wage earner was unemployed, the family received public assistance, or the family lived below the US Census Bureau’s poverty threshold for a given family size), not intact family structure (a binary variable indicating whether both biological parents lived in the household with G2) at the start of RYDS, G1’s age at first birth, G1’s depressive symptoms (a 7-item scale based on the CES-D that ranged from 1 to 5, in which a higher score was indicative of more depressive symptoms; Cronbach α = 0.87) at the start of RYDS, G1’s incidence of drug use (a binary indicator to contrast illicit drug use, to no use) at the start of RYDS, and G1’s alcohol use (a logged score of frequency of alcohol use times quantity of alcohol use) at the start of RYDS. Finally, we included 2 measures of the participant’s neighborhood at the start of RYDS: neighborhood arrest rate and concentrated poverty. The former is based on Rochester Police Department data and is expressed as the arrest rate per 100 people for the neighborhood G2 lived in during adolescence. The latter is based on the 1980 census data and reflects the proportion of each tract’s population living below the poverty level.

Missing Data

In the current study, we utilized data from 496 G2 participants of RIGS. This excludes 43 people who had missing data on the maltreatment indicators or provided no information on our key outcome of interest, financial strain. Individuals who were missing data on the maltreatment indicators (n = 5) did not significantly differ from those observed on the maltreatment indicators for any of the variables considered in this study. However, individuals who were missing data on financial strain (n = 39) did significantly differ from those observed on financial strain for several variables considered in this study. The primary reason for missing these variables is that G2 entered into parenthood later in life. For example, 18 G2 participants did not become a parent until 2009 or later and therefore G3 had not yet turned 8 years by the last available wave of data. Therefore, G2 participants who were missing the financial strain measures tended to be older when they had their first child (mean = 31.2 years; SD = 6.8 for those missing vs mean = 21.3 years; SD = 4.3 for those not missing; P < .05) and had more years of education (mean = 14.0 years; SD = 2.4 for those missing vs mean = 12.2 years; SD = 1.6 for those not missing; P < .05). Their primary caregiver (G1) also tended to have an older age at first birth (mean = 21.1 years; SD = 5.0 for those missing vs mean = 18.8 years; SD = 3.6 for those not missing; P < .05) and more education (mean = 12.2 years; SD = 3.0 for those missing vs mean = 11.2 years; SD = 2.0 for those not missing; P < .05). In addition, G2 participants missing the financial strain variables were more likely to be male (84.6% of those missing compared with 64.0% of those not missing financial strain were male; P < .05) and less likely to be Black (43.6% of those missing compared with 73.2% of those not missing financial strain were Black; P < .05). There were no significant differences as a function of missing data on financial strain for any other variables considered in the current study.

Analysis

To test the proposed developmental cascade model, we used a multilevel, path analysis estimated in Mplus version 8 (Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA). Level 2 of the multilevel model represented G2 participants, and level 1 represented the repeated measures of financial strain for each G2 participant from G3 age 8 years to G3 age 15 years. We fit a separate model for each measure of maltreatment. Each model included a random intercept to account for the nesting of measurement occasions in individuals. We estimated all models with a full information maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors. Therefore, we properly handled missing data on all endogenous variables under the assumption of missing at random (accessible missingness).21 We calculated the indirect effect via the mediators by using the product of coefficients method22 with robust standard errors (bootstrap confidence intervals are not available for multilevel models in Mplus). We used an α of 0.05 for all hypothesis tests.

RESULTS

We began our analysis with a focus on the G2 self-report measures of maltreatment before age 12 years. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1 as a function of G2 maltreatment status. We fit a total of 4 models for G2 self-reported child maltreatment; these models are reported in Table 2 (models 1 through 4). Model 1 compared G2 individuals who reported any type of self-reported maltreatment before age 12 years with G2 individuals who reported no maltreatment before age 12 years. When we adjusted for the confounders, we observed significant total, direct, and indirect effects of G2 self-reported maltreatment on G2 financial strain, with about one fourth of the total effect of maltreatment on financial strain indirect through the mediators. The G2 participants who reported maltreatment when they were a child reported significantly greater depressive symptoms and substance abuse during their adolescence. Substance abuse by G2 during adolescence was significantly associated with G2’s poorer educational outcomes as well as G2’s earlier entry into parenthood. Fewer accumulated years of education for G2, earlier entry into parenthood for G2, and G2 adolescent depressive symptoms were all directly and significantly related to greater financial strain when G2 became a parent (i.e., when G3 was between the ages of 8 and 15 years).

TABLE 1—

Descriptive Statistics for Each Considered Variable as a Function of the Maltreatment Variables: Rochester Youth Development Study and Rochester Intergenerational Study, Rochester, NY, 1988–2016

| G2 Self-Reported Maltreatment Before Age 12 Years |

G2 Official Maltreatment Ages 12–17 Years |

||||||

| Variable | No Maltreatment (n = 364), Mean (SD) or Proportion | Any Maltreatment (n = 132), Mean (SD) or Proportion | Neglecta (n = 62), Mean (SD) or Proportion | Physicala (n = 69), Mean (SD) or Proportion | Sexuala (n = 57), Mean (SD) or Proportion | No Record (n = 452), Mean (SD) or Proportion | Record (n = 44), Mean (SD) or Proportion |

| G2 average financial strain (G3 ages 8–15 y) | 0.66 (0.85) | 1.16 (1.11) | 1.39 (1.26) | 1.26 (1.11) | 1.16 (1.12) | 0.76 (0.95) | 1.07 (0.90) |

| G2 adolescent substance abuse | 1.30 (1.14) | 1.66 (1.10) | 1.68 (1.13) | 1.86 (1.13) | 1.75 (0.95) | 1.38 (1.15) | 1.61 (1.08) |

| G2 adolescent depressive symptoms | 2.25 (0.50) | 2.48 (0.49) | 2.53 (0.54) | 2.51 (0.41) | 2.55 (0.50) | 2.30 (0.51) | 2.43 (0.50) |

| G2 age at first birth, y | 21.42 (4.35) | 21.06 (4.24) | 21.25 (4.17) | 21.04 (4.15) | 19.96 (4.10) | 21.49 (4.36) | 19.62 (3.52) |

| G2 y of education | 12.21 (1.60) | 12.12 (1.55) | 12.20 (1.43) | 12.19 (1.63) | 12.10 (1.53) | 12.20 (1.56) | 12.07 (1.84) |

| G1 alcohol use | 0.99 (1.02) | 1.07 (1.03) | 1.14 (1.06) | 1.19 (1.07) | 1.18 (1.05) | 0.98 (1.02) | 1.35 (1.00) |

| G1 drug use | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| G1 depressive symptoms | 1.66 (0.69) | 1.73 (0.70) | 1.78 (0.71) | 1.77 (0.73) | 1.68 (0.62) | 1.67 (0.70) | 1.69 (0.70) |

| G1 y of education | 11.12 (2.09) | 11.30 (1.90) | 11.52 (1.93) | 11.14 (1.96) | 11.53 (1.40) | 11.20 (2.06) | 10.77 (1.75) |

| G1 age at first birth, y | 18.84 (3.75) | 18.56 (3.18) | 18.79 (3.40) | 18.36 (3.56) | 18.55 (3.12) | 18.85 (3.71) | 17.88 (2.21) |

| G2 did not live with both biological parents | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.93 |

| G1 low socioeconomic status | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.72 |

| G2 male | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.32 |

| G2 Black | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.81 | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.84 |

| G2 Hispanic | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.09 |

| G1 neighborhood arrest rate | 4.38 (2.04) | 4.36 (2.05) | 4.23 (2.05) | 4.60 (2.03) | 4.67 (2.09) | 4.38 (2.03) | 4.34 (2.21) |

| G1 neighborhood poverty | 0.34 (0.14) | 0.34 (0.13) | 0.33 (0.13) | 0.34 (0.13) | 0.36 (0.13) | 0.34 (0.14) | 0.33 (0.15) |

| G2 age at start of RYDS | 13.54 (0.75) | 13.63 (0.77) | 13.67 (0.70) | 13.65 (0.80) | 13.58 (0.74) | 13.57 (0.76) | 13.54 (0.75) |

Note. G1 = generation 1; G2 = generation 2; G3 = generation 3; RYDS = Rochester Youth Development Study.

Type of self-reported abuse (neglect, physical, sexual) is not mutually exclusive; participants reporting multiple types of abuse appear in each respective column.

TABLE 2—

Developmental Cascade Models for Each Indicator of Abuse: Rochester Youth Development Study and Rochester Intergenerational Study, Rochester, NY, 1988–2016

| G2 Self-Reported Maltreatment Before Age 12 Years |

G2 Official Maltreatment Ages 12–17 Years, Model 5, Any Record, b (95% CI) |

||||

| Indicator of Abuse | Model 1, Any Abuse, b (95% CI) | Model 2, Neglect,a b (95% CI) | Model 3, Physical Abuse,a b (95% CI) | Model 4, Sexual Abuse,a b (95% CI) | |

| G2 Financial strain regressedb on: | |||||

| G3 age | −0.05 (−0.09, −0.02) | −0.05 (−0.08, −0.01) | −0.05 (−0.09, −0.02) | −0.06 (−0.09, −0.02) | −0.06 (−0.09, −0.02) |

| G3 age*G3 age | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.02) | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.02) | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.02) | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.02) | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.02) |

| G2 age at first birth | −0.05 (−0.09, −0.01) | −0.03 (−0.08, 0.01) | −0.03 (−0.07, 0.01) | −0.05 (−0.09, −0.002) | −0.05 (−0.09, −0.01) |

| G2 y of education | −0.13 (−0.24, −0.03) | −0.18 (−0.30, −0.05) | −0.16 (−0.27, −0.04) | −0.13 (−0.25, −0.02) | −0.14 (−0.24, −0.03) |

| G2 adolescent depressive symptoms | 0.71 (0.43, 0.98) | 0.76 (0.44, 1.09) | 0.73 (0.42, 1.04) | 0.67 (0.35, 0.98) | 0.81 (0.53, 1.08) |

| G2 adolescent substance abuse | 0.04 (−0.09, 0.17) | 0.03 (−0.11, 0.18) | 0.05 (−0.10, 0.19) | 0.02 (−0.13, 0.17) | 0.05 (−0.08, 0.19) |

| Maltreatment | 0.58 (0.30, 0.86) | 0.73 (0.34, 1.12) | 0.78 (0.43, 1.12) | 0.53 (0.16, 0.89) | 0.41 (0.02, 0.80) |

| G2 age at first birth regressedc on: | |||||

| G2 adolescent depressive symptoms | −0.02 (−0.69, 0.66) | −0.19 (−0.90, 0.53) | −0.19 (−0.95, 0.56) | −0.16 (−0.90, 0.58) | 0.00 (−0.68, 0.68) |

| G2 adolescent substance abuse | −0.91 (−1.23, −0.58) | −0.85 (−1.19, −0.52) | −0.84 (−1.19, −0.50) | −0.90 (−1.26, −0.53) | −0.90 (−1.23, −0.57) |

| Maltreatment | 0.10 (−0.65, 0.86) | 0.07 (−0.87, 1.00) | 0.21 (−0.73, 1.16) | −0.28 (−1.32, 0.76) | −0.30 (−1.38, 0.79) |

| G2 y of education regressedc on: | |||||

| G2 adolescent depressive symptoms | 0.13 (−0.15, 0.41) | 0.18 (−0.11, 0.47) | 0.15 (−0.16, 0.45) | 0.21 (−0.09, 0.52) | 0.13 (−0.15, 0.41) |

| G2 adolescent substance abuse | −0.21 (−0.33, −0.08) | −0.22 (−0.35, −0.09) | −0.23 (−0.36, −0.09) | −0.24 (−0.38, −0.10) | −0.20 (−0.33, −0.08) |

| Maltreatment | 0.00 (−0.29, 0.29) | 0.03 (−0.30, 0.37) | 0.24 (−0.13, 0.61) | −0.06 (−0.48, 0.37) | −0.10 (−0.60, 0.40) |

| G2 adolescent depressive symptoms regressedc on: maltreatment | 0.22 (0.12, 0.32) | 0.30 (0.16, 0.44) | 0.24 (0.13, 0.35) | 0.26 (0.12, 0.39) | 0.06 (−0.08, 0.20) |

| G2 adolescent substance abuse regressedc on: maltreatment | 0.30 (0.09, 0.52) | 0.26 (−0.05, 0.58) | 0.46 (0.18, 0.74) | 0.49 (0.25, 0.73) | 0.34 (0.05, 0.63) |

| Effect of maltreatment on financial strain | |||||

| Total effect | 0.76 (0.47, 1.06) | 0.97 (0.56, 1.38) | 0.95 (0.59, 1.32) | 0.76 (0.37, 1.14) | 0.53 (0.12, 0.93) |

| Indirect effect | 0.18 (0.07, 0.29) | 0.24 (0.08, 0.40) | 0.18 (0.04, 0.32) | 0.23 (0.08, 0.38) | 0.12 (−0.05, 0.28) |

Note. CI = confidence interval, G2 = generation 2, G3 = generation 3. All outcomes are adjusted for the potential confounders listed in the measurement section.

Type of self-reported abuse (neglect, physical, sexual) is not mutually exclusive; participants reporting multiple types of abuse appear in each respective column.

Negative binomial regression (log count).

Linear regression.

Models 2 through 4 in Table 2 present results for self-reported maltreatment broken into types—neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse. The results of the models are generally the same, with a significant total, direct, and indirect effect of each type of G2 self-reported maltreatment on G2 financial strain in each case.

Last, we considered official CPS reports of G2 maltreatment during adolescence (age 12–17 years). The results are reported under model 5 in Table 2. While we observed a significant total and direct effect of a CPS report of G2 maltreatment on G2 financial strain, the indirect effect through the mediators was in the expected direction, but not statistically significant. The primary difference between the self-report models (models 1–4) and the CPS model (model 5) is that a CPS report of G2 child maltreatment was not associated with G2 depressive symptoms in adolescence, whereas G2 self-reported maltreatment was significantly associated with G2 elevated symptoms of depression.

DISCUSSION

Our study adds to the limited number of longitudinal cohort studies that examine the long-term consequences of maltreatment on socioeconomic outcomes. All types of abuse were associated with greater financial strain when the victim became a parent, and we found evidence that about one fourth of the effect of self-reported child maltreatment on financial strain during parenthood could be explained by the mediators in our proposed developmental cascade model.

Our findings add rigor to the existing literature on the ill effects of maltreatment. We were able to control for many preexisting confounders that cross-sectional studies simply cannot. Also, we were able to follow children with maltreatment experiences through adolescence, emerging adulthood, and parenthood, which allows for a cross-generational understanding of the conditions (e.g., financial strain) within which children are now being raised based on parents’ history of childhood victimization.

Our results offer important implications for public health practice. Given that financial strain is associated with myriad negative consequences, including poorer health for the individual,23 poorer family climate,24 and poorer child development,25 interventions designed to intervene in the cascade between child maltreatment victimization and the economic consequences of the abuse are critical. The results of our study provide direct support for policies that seek to provide economic help to families as a child maltreatment prevention strategy, including those evidence-based policies that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and others have suggested are strategic for achieving multiple public health goals. Programs and policies that are supportive of families and provide at-risk parents with resources and environments that better equip them to provide safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments for their children may help affected families prosper.26 For example, policies that strengthen family economics—livable wages, paid family leave—not only alleviate parental stress, a known risk factor for child maltreatment, but also allow parents to provide resources to meet their children’s basic needs to thrive.27–29 Also, family-friendly work policies such as predictable work schedules can help bolster family connectedness and attachment.30,31

Building on these recommendations, the CDC recently included such policies in their technical package on child abuse and neglect prevention. There is evidence that policies that strengthen household financial security may prevent child maltreatment.26 Furthermore, policies that target the key areas of neighborhood conditions; learning and development opportunities; employment and community development, norms, and customs; social cohesion; and health promotion and disease prevention should be prioritized, as highlighted by Williams et al.32 Policy-level strategies are likely to have the largest impact on child maltreatment prevention by ensuring the conditions in which families can thrive, thereby increasing the likelihood that a victim of maltreatment will not go on to continue the cycle of maltreatment.

In addition, we identified several important mediators of the effect of maltreatment on subsequent outcomes, perhaps the most important of which is the harm to adolescent health and well-being. Self-reported child maltreatment was directly associated with depressive symptoms and substance abuse in adolescence. Depressive symptoms in adolescence were robustly associated with financial strain in adulthood, while substance abuse in adolescence was associated with compromised educational attainment and earlier entry into parenthood. These findings underscore the importance of interventions for at-risk adolescents to address these behavioral consequences of maltreatment before they go on to have an impact on other aspects of the individual’s life. In recognizing patterns that can arise from maltreatment early in life, integrated, trauma-informed interventions for treating the distress related to child maltreatment may both curb individual distress and increase the likelihood of resilience following abuse.33

Limitations

Along with its strengths, it is important to recognize the limitations of our study. First, the sample size used in this research was relatively small, though it is in line with other intergenerational, longitudinal studies. The small sample size, in conjunction with the relative rarity of maltreatment, precludes the examination of subgroup differences. Future studies with larger samples that can examine differential effects of maltreatment by sex or race/ethnicity are important. Another limitation is that we relied on self-report measures from a single reporter for most of the key constructs in the study. This common method bias may have had an impact on the findings of our study and may also limit the study’s correspondence to other authors who might define or measure these constructs differently. For example, substance abuse in our study considered only alcohol and cannabis use during G2 adolescence given other types of use were not assessed (e.g., cigarette use) or were extremely rare (e.g., other illicit drug use). As described in the Methods section, G2 participants who entered into parenthood later in adulthood (mid-30s and beyond) were not included in the current investigation because their child had not yet turned 8 years, the first year that we considered financial strain in this analysis. Therefore, our results may not be generalizable to older parents. It is also important to note that the Rochester studies represent families who lived in Rochester, New York, in the mid-1980s, and the extent to which these findings generalize to other populations is unknown.

We also acknowledge that the measurement of maltreatment is a recognized challenge, and although our approach has strengths, there are still limitations to consider. First, our choice for comparing forms of self-reported abuse is one method, but other methods could have been used (e.g., latent class analysis of types of abuse, a count of multiple types of abuse, or an assessment of the severity of abuse). Furthermore, given the small sample size, we did not consider chronicity of abuse (i.e., abuse that extended from childhood into adolescence), but this is an important consideration for future studies, particularly given that those who had an official record of maltreatment were more likely to self-report abuse during childhood (22.7% reported neglect, 36.4% reported physical abuse, and 27.3% reported sexual abuse) as compared with those without an official record of maltreatment (11.5% reported neglect, 11.7% reported physical abuse, and 10.0% reported sexual abuse). In addition, emotional abuse was measured as part of the official record of maltreatment, but was not available in the self-report. Last, given the small number of people with an official report of maltreatment, we were unable to break out subtypes of official reports of abuse.

Future Directions

Our study controlled for many contextual factors that theoretically preceded maltreatment that the parent experienced when he or she was a child (e.g., socioeconomic variables and neighborhood conditions pertaining to the family of origin). While such controls make the finding of child maltreatment and financial strain’s continued impact on family climate noteworthy, future efforts that explore such conditions themselves as explanatory are warranted. Safe, stable, nurturing environments, including the community and sociopolitical environments, likely confer unique protective effects on health, well-being, and prosperity. Unfortunately, the research is clear that the opposite is true as well, that there are conditions that disproportionately create and exacerbate risks for violence and victimization across generations in the absence of protective factors. Much more work is needed to build on our findings and carefully examine this complex web of relationships.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support for the Rochester Youth Development Study has been provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA020195, R01DA005512), the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (86-JN-CX-0007, 96-MU-FX-0014, 2004-MU-FX-0062), the National Science Foundation (SBR-9123299), and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH56486, R01MH63386). Technical assistance for this project was also provided by a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant (R24HD044943) to The Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the University at Albany. These analyses were supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We thank Adrienne Freeman-Gallant, PhD, for her assistance in compiling the data set for this investigation, and the research staff and participating families of the Rochester studies for making this study possible. We also thank Dacre Kurth for her editorial assistance. We extend our gratitude to the many families who participated in these important research projects. These analyses could not have been conducted without their help and willingness to share their lives with study investigators.

Note. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the funding agencies.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The Rochester Youth Development Study and the Rochester Intergenerational Study were approved and monitored by the institutional review board at the University at Albany.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garner AS, Shonkoff JP, Siegel BS et al. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e224–e231. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):1–31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metzler M, Merrick MT, Klevens J, Ports KA, Ford DC. Adverse childhood experiences and life opportunities: shifting the narrative. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;72:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masten AS, Cicchetti D. Developmental cascades. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22(3):491–495. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nanni V, Uher R, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):141–151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonmyr L, Thornton T, Draca J, Wekerle C. A review of childhood maltreatment and adolescent substance use relationship. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2010;6(3):223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costello EJ, Copeland W, Angold A. Trends in psychopathology across the adolescent years: what changes when children become adolescents, and when adolescents become adults? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(10):1015–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall WD, Patton G, Stockings E et al. Substance use in young people 2: why young people’s substance use matters for global health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):265–279. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dupéré V, Dion E, Nault-Brière F, Archambault I, Leventhal T, Lesage A. Revisiting the link between depression symptoms and high school dropout: timing of exposure matters. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(2):205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noll JG, Shenk CE, Putnam KT. Childhood sexual abuse and adolescent pregnancy: a meta-analytic update. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(4):366–378. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Helfand M. Ten years of longitudinal research on U.S. adolescent sexual behavior: developmental correlates of sexual intercourse, and the importance of age, gender and ethnic background. Dev Rev. 2008;28(2):153–224. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58(1):175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mistry RS, Lowe ED, Benner AD, Chien N. Expanding the family economic stress model: insights from a mixed-methods approach. J Marriage Fam. 2008;70(1):196–209. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prawitz AD, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, O’Neill B, Kim J, Drentea P. InCharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: development, administration, and score interpretation. Financ Couns Plan. 2006;17(1):34–50. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zielinski DS. Child maltreatment and adult socioeconomic well-being. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(10):666–678. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Currie J, Widom CS. Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well-being. Child Maltreat. 2010;15(2):111–120. doi: 10.1177/1077559509355316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slack KS, Berger LM, Noyes JL. Introduction to the special issue on the economic causes and consequences of child maltreatment. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;72:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thornberry TP, Henry KL, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Nadel EL. Key findings from the Rochester Intergenerational Study. In: Eichelsheim VI, van de Weijer SGA, editors. Intergenerational Continuity of Criminal and Antisocial Behavior: An International Overview of Current Studies. London, England: Routledge; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(2):147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58(1):593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szanton SL, Thorpe RJ, Whitfield K. Life-course financial strain and health in African-Americans. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(2):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neppl TK, Senia JM, Donnellan MB. Effects of economic hardship: testing the family stress model over time. J Fam Psychol. 2016;30(1):12–21. doi: 10.1037/fam0000168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnett MA. Economic disadvantage in complex family systems: expansion of family stress models. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2008;11(3):145–161. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0034-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fortson BL, Klevens J, Merrick MT, Gilbert LK, Alexander SP. Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect: A Technical Package for Policy, Norm and Programmatic Activities. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossin-Slater M, Ruhm CJ, Waldfogel J. The effects of California’s Paid Family Leave Program on mothers’ leave-taking and subsequent labor market outcomes. J Policy Anal Manage. 2013;32(2):224–245. doi: 10.1002/pam.21676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stith SM, Liu T, Davies LC et al. Risk factors in child maltreatment: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggress Violent Behav. 2009;14(1):13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Women’s Law Center. Helping parents in low-wage jobs access affordable child care: opportunities under the reauthorized child care and development block grant. 2015. Available at: https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/ccdbg_reauthorization_low-wage_workers_issue_brief_.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

- 30.Forget EL. The town with no poverty: the health effects of a Canadian guaranteed annual income field experiment. Can Public Policy. 2011;37(3):283–305. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aumann K, Galinsky E. The state of health in the American workforce: does having an effective workplace matter? Families and Work Institute. 2011. Available at: http://familiesandwork.org/site/research/reports/HealthReport_9_11.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

- 32.Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, Mohammed SA. Moving upstream: how interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(suppl):S8–S17. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338382.36695.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magruder KM, Elmore DL, McLaughlin KA A public health approach to trauma: implications for science, practice, policy and the role of ISTSS. International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2015. Available at: https://www.istss.org/getattachment/Education-Research/White-Papers/A-Public-Health-Approach-to-Trauma/Trauma-and-PH-Task-Force-Report.pdf.aspx. Accessed July 9, 2018.