Abstract

Fear is now commonly used in public health campaigns, yet for years ethical and efficacy-centered concerns provided a challenge to using fear in such efforts. From the 1950s through the 1970s, the field of public health believed that using fear to influence individual behavior would virtually always backfire. Yet faced with the limited effectiveness of informational approaches to cessation, antitobacco campaigns featured fear in the 1960s. These provoked little protest outside the tobacco industry. At the outset of the AIDS epidemic, fear was also employed. However, activists denounced these messages as stigmatizing, halting use of fear for HIV/AIDS until the 21st century. Opposition began to fracture with growing concerns about complacency and the risks of HIV transmission, particularly among gay men. With AIDS, fear overcame opposition only when it was framed as fair warning with the potential to correct misperceptions.

Fear of disease has been a public health messaging trope in popular journalistic culture for more than a century and a half. Around the turn of the 20th century, advertisements appeared in popular magazines that featured gargantuan flies menacing cherubic pink-cheeked babes, warning mothers to maintain proper hygiene and to vaccinate these innocents.1 Sexually transmitted infection campaigns used a spectrum of scare tactics from the early 20th century through World War II, presenting images of skulls and crossbones or pictures of corrupt (and corrupting) women beckoning from barstools or alleyways.2

Public health scare campaigns and panic mongering had, on occasion, been the subjects of popular or medical challenge in the period before World War II.3 Paradoxically, fear came under more systematic attack in the Cold War era, in large measure because of increasing weariness with the “politicization of terror.”4(p66) An antifear canon guided thinking in the field of public health education from the 1950s into the 1970s. Although it remains a powerful assumption by some, the orthodoxy that fear never works and, therefore, fear must always be a negative, irrational emotion has been compelled to yield to new evidence and the changing perspective of public health advocates.

In the social sciences and advertising literature, fear-based campaigns have been defined as efforts to make individuals internalize a threat—of death, disease, suffering, loss of beauty, loss of social status, even social exclusion. A fear-based appeal need not make populations quake with anxiety or recoil in disgust when faced with gruesome images of death and disfigurement. Rather, fear-based messaging, whether an image or narrative, can make a threat feel immediate and make target audiences feel vulnerable. Some fear-based appeals even rely on sharply framed humor.5

In the early 1980s, ethicists began to grapple with the question of whether fear could pose a threat to the autonomy of its targets, that is, whether it could amount to manipulation by triggering irrational emotions. More recently, bioethicists have worried that, intentionally or not, rational or not, grotesque or darkly comical, fear-based efforts produce a sense of shame, thus explicitly or implicitly employing the social power of stigmatization.6

We explore the history of fear-based campaigns through the two challenges to public health that best exemplify the history of fear-based messaging in the post–World War II era: tobacco, for which the use of fear was commonplace by the 1970s, and HIV, for which the use of fear campaigns has been hotly contested until very recently. In the case of tobacco, because of the lethality of this single product and a deceitful corporate actor, the use of fear has met little opposition. In the case of AIDS, the existence of groups already susceptible to discrimination and stigmatization created a very different sociopolitical context for the first three decades of the epidemic. Comparing the use of fear in antitobacco campaigns with its use in HIV/AIDS prevention campaigns reveals a striking, neglected continuity: when fear has been successfully framed as fair warning with the potential to correct misperceptions rather than as mere scapegoating, it can overcome opposition, even when that opposition has deep rights-based roots.

TOBACCO: FROM STATISTICS TO MESSAGING

In the early 1950s, researchers began reporting that smoking was associated with lung cancer. As public health sought to publicize the link, it initially approached smoking as a problem of information. Efforts to combat the threat of tobacco were, in the 1950s, primarily numerical in this decidedly “statistical era.”7 Numbers were objective and neutral; they conveyed the imprimatur of science. Public health, like clinical medicine, seized on the “cool thought” language of odds and probability in establishing authority.8 Media reports on smoking were newly peppered with risk assessments: “The odds of a nonsmoker dying of cancer in the next 12 months are 10,000 to 1. They shorten to 300 to 1 in the case of a heavy smoker”9(p23); “The two-pack-a-day smoker multiples his chances of lung cancer 52 times.”10(p3)

In this context, the role of fear was commonplace yet increasingly subject to challenge. On one hand, public health was successfully using fear as a tool for institution building.3,11 On the other, the public, advocacy groups, scientists, and thought leaders were growing not only wary but skeptical of fear.12 In their landmark 1953 study, Irving Janis and Seymour Feshbach concluded that the use of fear consistently backfired.13 Leona Baumgartner, the first woman to head the New York City Department of Health and the first health commissioner to systematically exploit both radio and television, managed fears of topics as diverse as fluoridation, radioactive fallout, and polio. Although she acknowledged struggling with crises and profound fears behind the scenes, in front of the cameras she hewed to her belief that it is “very important not to scare parents,” or anyone, “to death.”14 Consequently, she always stressed that any health department public communications and, especially, educational materials must be “based on good scientific facts.”15

Tobacco companies had relied on an image of physicians and the authority of medical science to advertise cigarettes through the 1940s into the early 1950s,16 and national voluntary organizations mirrored this approach. In 1958, for example, an American Cancer Society (ACS) leaflet underscored the idea that “to smoke or not to smoke is a personal decision” and went on to lay out the odds of all the different health consequences of smoking in multiple numerical ways. Public health practitioners and clinicians believed that risk information alone would lead individuals to make the obviously superior, logical choice,17 to “decide,” for example, “whether smoking is worth the possible risk of cancer.”8 Such risk calculations describing the hazards of smoking (and other behaviors and products) in multiplicative terms18 continued through the 1960s, reflecting the tenacity of belief “in the power of evidence to transform” practice and behavior.7

In 1964, when Surgeon General Luther Terry warned that smoking was linked to cancer and heart disease, public health responded by attempting to add an edge to what might otherwise have seemed like cold, impersonal data. For example, efforts to encourage individuals to calculate their years of life lost reflected a perceived need to drive home and personalize risk. Risk factor scores and health hazard appraisal tools, which sought to individualize the risk by calculating a person’s expiration date, became a popular means to both quantify and personalize bad habits. Jane Brody, who wrote health columns for the New York Times, wanted readers to see a flashing red light: “Your risk factor score may be the only warning you get of the damage being done,” she wrote in 1977.19(p49)

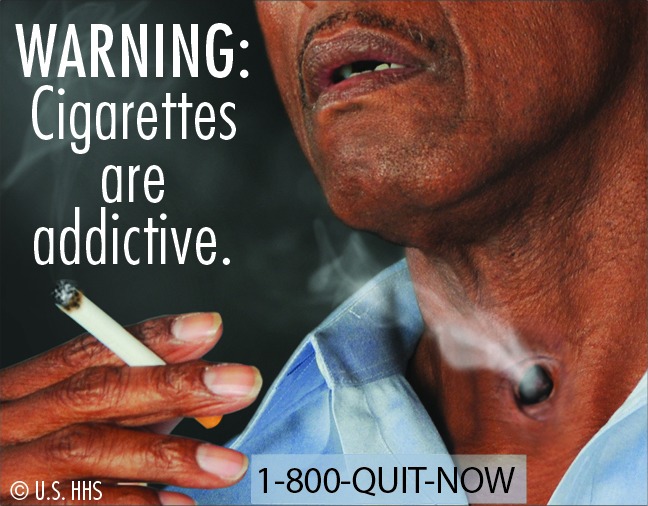

Example of Fear-Based Tobacco Messaging. Reproduced with permission by the US Department of Health and Human Services.

The assumption, then, remained strong that armed with the statistical odds Americans would make logical health choices—it was just a question of how best to present the data. Conversely, however, there was a collective effort to make risk sound an internal alarm, which anticipated that the numbers game and craze to “figure your chances” was reaching saturation point.20 Even Leona Baumgartner, who had so studiously avoided tactics that even hinted of fear, warned that chronic disease was a new dilemma for public health. For a preamble to CBS’s National Health Test, which aired on national television in January 1966, she authored the introduction titled “Knowing Is Not Enough” and warned, “Man’s own contribution to the potency and distribution of disease and human disorders is so alarming that in many cases it almost seems to cancel out the contribution which medical sciences has made.”21(p1) Although Baumgartner did not go so far as to endorse fear, she underscored that information had to carry “personal meaning” for each individual if it was to have “a motivating effect.”21(p1)

But smoking was not just any behavior. It was encouraged by a powerful advertising industry. By the mid-1950s, although filtered products began to figure prominently in industry advertising, health claims were supplanted by appeals to smoking cigarettes as a lifestyle choice.16 Public health was confronted with a social world suffused by advertisements promoting the smoking of cigarettes as enjoyable, relaxing, socially desirable, and seductive. In response to new forms of commercial persuasion, public health shifted tactics to compete, adding an emotional charge to the barrage of information. In 1967 John Banzhaf, a public interest lawyer and antismoking activist, filed a petition with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) asking it to apply the fairness doctrine to antismoking advertisements and demanding broadcast time proportional to cigarette commercials. The FCC subsequently mandated free airtime: for every three tobacco pitches, there would be one counteradvertisement.22

Although public awareness of the troubling facts and data linking smoking and disease had made a marked impact on the prevalence of smoking, advocates and public health officials came to believe that more was needed. An earlier academic consensus on scientific communication and behavior change had lost its hegemonic status—at least when the behavior in question was smoking. Public service announcements sponsored by voluntary associations such as the ACS and American Lung Association (ALA) evoked fear and guilt—initially only gently—of harming children, family, friends, and, finally, oneself.22 The tone became sharper in the late 1970s. The ACS and the ALA increasingly painted smoking as a form of personal misbehavior that would and, indeed, should lead to social rejection.23–25 Internal tobacco industry documents revealing a sustained pattern of corporate deception and manipulation provided a critically important social warrant for fear.

The pioneering bioethics literature offered cautious support for the use of fear. Dan Wikler, Ruth Macklin, Tom Beauchamp, Gerald Dworkin, and Ruth Faden26—all central to the intellectual and philosophical foundations of bioethics—struggled with the moral dilemmas posed by public health campaigns during a period of concern over behavior control. Although all were concerned that health messaging not even inadvertently cross the boundary from education to manipulation, there was general agreement that it was vital for individuals to understand the risks of behavior in “an emotionally genuine manner.”27(p77) When information alone, communicated in the neutral language of science, was insufficient to convey the seriousness of a threat and “break through the fog” of denial, adding emotion could enhance autonomy.28

Although we focus here on what happened in the United States, it is important to note that it was Australia that led the way in the 1990s, using images of arteries that looked like sausage skins packed with cottage cheese to counter the allure of the cigarette. Antitobacco ads began to use graphic imagery powerful enough to break through the “fog of denial” among smokers, no longer depicted as wrongdoers, but victims.29,30 The goal, explained campaign theorists and developers, was to produce “a strong visceral ‘yuk!’”28

New York City moved to the vanguard of this new hard-hitting approach from 2002 to 2013, during the administration of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, known for aggressive, paternalistic public health policies. Health officials were determined to call on what extensive review of the literature and their own focus groups of current smokers were telling them: it was time for some gore. Remarkably, considering the antagonism to such approaches that defined the early outlook of public health officials involved in combatting AIDS, the antitobacco movement was able to expand and intensify the use of fear-based appeals and shield the practice of denormalization from the charge that such messages intentionally and inappropriately stigmatized smokers. However, nothing more tellingly reveals the embrace of fear and gore in the public health response to smoking than the graphic tobacco warnings that the US Food and Drug Administration sought to place on cigarette packages. Although ruled a violation of the First Amendment because they constituted compelled speech, for tobacco-control advocates, the warnings were critical for breaking through the fog.

Graphic messages continued through 2017 with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) nationwide Tips From Former Smokers Campaign, which features real Americans who describe their own challenges living with smoking-related illnesses.

HIV/AIDS: THE FALL AND RISE OF THE GRIM REAPER

Although they would ultimately face deep criticism, emotionally laden, fear-based appeals were one of the hallmarks of the early global AIDS campaign. The most vivid was, perhaps, Australia’s Grim Reaper campaign depicting Death—a shrouded, skeletal figure—using a bowling ball to mow down men, women, and children.31

The approach resonated with some early gay activists. Larry Kramer, in a controversial piece in the gay weekly New York Native, argued that there was a moral imperative to “scare the shit” out of gay men.32 Randy Shilts, a gay journalist who meticulously chronicled the early years of the epidemic, critiqued the opposition to the use of fear-based warnings of some early gay activists. The stance, “Don’t offend the gays and don’t inflame the homophobes,”33(p69) he argued, paved the road to crisis. He concluded, “It would always be the unwritten policy of health bureaucrats throughout the epidemic that, when in doubt, don’t scare the horses.”33(p107)

If gay men were concerned about rolling back whatever progress had been made in the struggle against homophobia and sodomy statutes, public health professionals involved in AIDS prevention were concerned that the use of fear—despite what might be construed as the permission given by some outspoken gay advocates—would be seen as panic mongering, particularly amid widespread, unfounded fears that AIDS could be transmitted through casual contact. Jim Curran, a prominent CDC official during the first days of AIDS, observed that this new infectious threat taught public health the limits of heavy-handed tactics. Curran recalled both politicians and the public as acting “like a rheostat,” at any particular moment generating a current that pushed the national mode from “Complacency (Neglect) to Fear (Panic).” He thus described the importance of throwing into bold relief, in early public service announcements, all the ways that this new disease could not be spread. “The smoking people are all social control people,” he observed. “They come from a different point of view.” With AIDS, he said, “things were going in the wrong direction,” making it imperative to quell rather than stir fears (A.L. Fairchild interview of James Curran, April 2014). Public health officials had, in addition, more pressing challenges: how to convey sex-positive warnings to gay men in a society in which public health messaging virtually never addressed sexuality as a pleasurable activity and certainly never with gay men.

Curran’s views were profoundly influenced by gay activists who sought not simply to change behavior but to frame sexual liberation as healthy, arguing that fear-based “missionary” measures were moralistic, repressive, archaic, and, ultimately, damaging.13,34 In addition, his understanding was informed by the health and human rights perspective in global AIDS policy. Interventions with any kind of paternalistic, coercive, or stigmatizing dimensions became the subjects of sharp critique. Preeminent figures in the health and human rights movement spoke out on this. Johnathan Mann, who headed the World Health Organization’s first concerted effort to confront AIDS, wrote, “The evolving HIV/AIDS pandemic has shown a consistent pattern through which discrimination, marginalization, and stigmatization and, more generally, a lack of respect for the human rights and dignity of individuals and groups heightens their vulnerability to being exposed to HIV.”35(p20–21) Peter Piot, director of the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, asserted that the “effort to combat stigma” was at the top of his list of the “five most pressing items on [the] agenda of the world community.”36(p14)

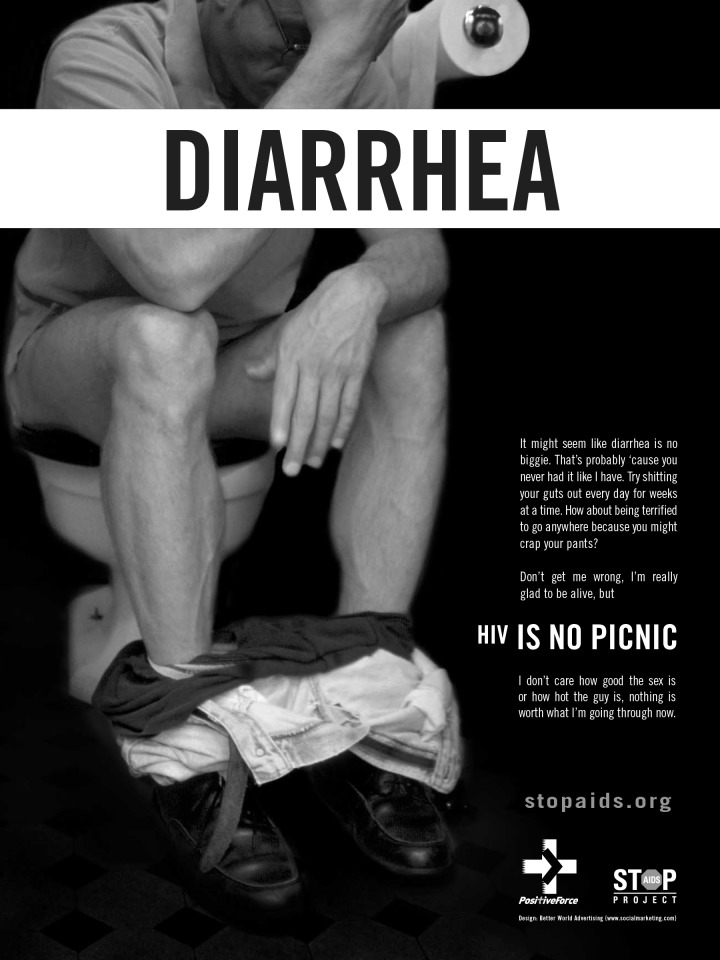

Example of Fear-Based HIV/AIDS Messaging. Reproduced with permission by the San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

AIDS activists quickly came to regard fear as inherently stigmatizing.36 Some researchers described the subsequent emergence of a solid antifear orthodoxy that uniformly rejected fear in favor of sex-positive approaches.13

The epidemiological trajectory of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in countries with high resources and affluent, activist gay populations seemed to affirm the logic that, in fact, fear was not necessary to combat an epidemic. Yet it would become obvious in the early 21st century that AIDS had not been conquered. Even as overall case rates declined in the United States, there were upticks in the rate of HIV infections among young minority men of color who had sex with men. Latinos were twice as likely and Blacks were four times as likely to be infected with HIV than were Whites.37,38

Alarm that these groups were not getting the message sparked new, vigorous responses to HIV. Created by the grassroots Stop AIDS Project (SAP), “HIV is no picnic” exposed fissures among activists worried about a resurgence of AIDS within a gay community grown weary of safer sex messages.39 San Francisco, Calilfornia’s HIV Health Services Planning Council, a community advisory body, embraced the campaign. It argued that it was time for a reality-based approach, particularly because of the fantasy vision of living with HIV promoted by the pharmaceutical industry.40 Although several hundred people signed a petition to end the campaign, SAP’s program director responded to the petition by arguing, “The HIV-positive guys who make up our Positive Force Program have been waiting to tell negative guys how tough it can be to live with HIV. We consider this a truth-in-advertising campaign.”41 Baltimore, Maryland, where Mayor Martin O’Malley declared a state of emergency in the face of increasing HIV infections, also adopted hard-hitting poster campaigns in 2002.42

Although New York City did not use a fear-based approach for another eight years, the San Francisco and Baltimore campaigns generated animated discussion within the city’s gay community. In November 2003, CBS’s 60 Minutes covered a packed open meeting at a gay community center in Manhattan chaired by actor and playwright Harvey Fierstein. He had joined the fray with a New York Times op-ed challenging the normalization of HIV. As had some activists in San Francisco, Fierstein blasted the message of drug companies as “lies. The truth is that AIDS is not fun,” he stressed. “It’s not sexy or manageable. AIDS is a debilitating, deforming, terminal and incurable disease.”43

As was true in the history of tobacco, renewed interest in fear was not limited to the United States. The US debates reflected revitalized international discussion about the need for a vigorous response to AIDS in the 21st century. In some instances, it was youth groups who proved warm to the use of fear.44 In other instances, health officials and activist groups aimed to shake sexually active populations—gay and straight—out of complacency, about HIV and all sexually transmitted infections. “You’ll feel like you’re peeing razor blades,” warned one campaign variant that urged both testing and treatment.45–48 Pharmaceutical companies once critiqued for promoting complacency and downplaying the consequences of lifelong HIV infection likewise felt a new license to scare.49

The new openness to using fear emerged at a moment of increasing concern about the burdens imposed on communities of color by wealth inequality, enduring racism, mass incarceration, and deeply rooted distrust of public health expertise. It was in this charged context that New York City launched a graphic, even shocking, campaign in 2010 called “It’s Never Just HIV.” This campaign targeted young men of color who had sex with men, like the ones who had, in focus groups, urged health officials to deliver a more potent message. Despite this important support, the campaign’s graphic images of coinfections like anal cancer, which seemed to shame the young Latino and Black gay men pictured in the campaign, provoked tremendous opposition on the part of many in the gay community.50 Predictably, Larry Kramer supported the campaign and wrote to colleagues, “This ad is honest and true and scary, all of which it should be. H.I.V. is scary, and all attempts to curtail it via lily-livered nicey-nicey ‘prevention’ tactics have failed.”51

FEAR REDUX: FEAR, STIGMA, AND EVIDENCE

The 1980s had seen a relatively unified gay and public health community when it came to fear-based campaigns: there was wide agreement that gay men should not become the culprits in an infectious disease epidemic. After 2002, pharmaceutical advertising strategies combined with concern that a community had lost a sense of urgency, that orthodoxy would no longer hold. Even so, there remained no single product to target. Hard-hitting approaches remained controversial, but not unthinkable.52 In sharp contrast, as tobacco ads began to hit harder and harder, there emerged, with few exceptions,53 no rights-based opposition. Indeed, denormalization of smoking has been embraced as a legitimate public health strategy. Despite some early public health efforts to explicitly stigmatize smokers, as well as smoking, Big Tobacco emerged as the clear culprit. Fear provided an emotional yet rational antidote to a history of half-truths and outright lies.

The changing politics of fear-based campaigns took place against the backdrop of a steadily growing empirical literature making the case that fear, delivered correctly, worked.26 A groundbreaking 2015 meta-analysis in the Psychological Bulletin, a leading journal in the field of psychology, was free of ambiguities and uncertainties. On the basis of studies conducted between 1962 and 2014, the authors concluded that fear appeals were effective at positively influencing attitudes, intentions, and behavior; there were very few circumstances under which they were not effective, and there were no identifiable circumstances under which they backfired and led to undesirable outcomes such as stigma.

Despite the steadily mounting evidence, in 2015, with some 30 years of experience with HIV prevention campaigns as a backdrop, the state health department of Arizona embraced a “new” initiative. “We . . . learned from the past. We didn’t want to shock and scare and judge the people we were talking to. . . . The research says that shocking and embarrassing and shaking your finger at the potential consumer does the exact opposite [of what you intend]. It makes them hide.”52

The stance of health officials in Arizona underscores that potential challenges are not so easily resolved. Concern about stigma remains an important consideration. An important body of literature has linked HIV-related stigma to adverse health outcomes.54,55 Additionally, fear—fear of disclosure, fear of losing friends, fear of family rejection—has been identified as a component of HIV-related stigma.54–57 But evidence of the toxic impacts of stigma are not the equivalent of asserting that fear must always produce stigma or that no efforts to mitigate stigma can be effective.58

Just as it is important not to paper over the evidence to make the case that fear never works, it is critical not to hew to a history suggesting that fear has and will continue to be rejected by communities at heightened risk of disease and death. Although the human rights perspective on fear has remained unwavering, a remarkably nuanced bioethics discussion has made clear that evoking strong emotions such as fear can be morally justified. Some even argue that noncorrosive, noncoercive forms of stigma might be warranted.59

Central to the ability of fear-based appeals to gain traction, then, has been some degree of social consensus on the part of communities that, in the face of persistent and unappreciated risks, they are owed the protection that fear-based campaigns might well provide. Importantly, even the strongest supporters of emotionally evocative campaigns have never suggested that fear is enough. Fear-based appeals alone cannot be an assault on the social determinants of health. To the extent that they fail to change the underlying conditions that generate disease, fear-based campaigns might well be viewed as a scolding nanny who makes us feel bad but fails to help us change. At worst, they might rightly be denounced as a pretext for neglecting the structural forces that produce disease and, indeed, a mechanism for blaming and shaming those at heightened susceptibility.

Anxiety about overstepping boundaries will undoubtedly persist. And certainly efforts to counteract irrational fears will continue to define public health approaches. But it is important to underscore the fact that although fear can be irrational, it is not inherently so. Martha Nussbaum, who made a trenchant case against stigma as a tool for behavior change, made an equally compelling case for the idea that emotions, fear included, “are suffused with intelligence and discernment.”60(p1) Whether hard-hitting messages will be employed in public health campaigns and how such efforts will be received depend on both political and social factors. They cannot, however, be simply dismissed as tarnished relics of the past that lack social, ethical, or evidentiary foundations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank the Greenwall Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant R25GM62454) for providing funding that allowed us to complete this study.

We wish to thank Gerald Oppenheimer, who generously shared relevant documents from the American Cancer Society. We wish to thank the US Department of Health and Human Services and the San Francisco AIDS Foundation for granting us permission to use images from their public health campaigns.

Footnotes

See also Chapman, p. 1120.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tomes N. The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women, and the Microbe in American Life. Reprint edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999. [PubMed]

- 2.Brandt AM. No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States Since 1880. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fairchild AL, Johns DM. Don’t Panic! The “excited and terrified” public mind from yellow fever to bioterrorism. In: Peckham R, editor. Empires of Panic: Epidemics and Colonial Anxieties. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2015. pp. 155–180. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyer P. By the Bomb’s Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Unger LS, Stearns JM. The use of fear and guilt messages in television advertising: issues and evidence. In: 1983 AMA Educators’ Proceedings, Series 49. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association; 16–20.

- 6.Guttman N, Salmon CT. Guilt, fear, stigma and knowledge gaps: ethical issues in public health communication interventions. Bioethics. 2004;18(6):531–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2004.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marks HM. The Progress of Experiment: Science and Therapeutic Reform in the United States, 1900–1990. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergman H. Scientists report “definite” link with smoking and cancer deaths. Atlanta Daily World. June 22, 1954:1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shepard G. Lung cancer rise linked with tars in cigarette smoke. Washington Post. December 14, 1953:23. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smoking Cancer Ratio Reported. Baltimore Sun. February 21, 1954:3.

- 11.Fee E, Brown TM. Preemptive biopreparedness: can we learn anything from history? Am J Public Health. 2001;91(5):721–726. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrison D. “Our skirts gave them courage”: the civil defense protest movement in New York City, 1955–1961. In: Meyerowitz J, editor. Not June Cleaver: Women and Gender in Postwar America, 1945–1960. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1994. pp. 201–226. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green EC, Witte K. Can fear arousal in public health campaigns contribute to the decline of HIV prevalence? J Health Commun. 2006;11(3):245–249. doi: 10.1080/10810730600613807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baumgartner L. Leona Baumgartner, Letter to Mrs. Petty Prince. May 18, 1955. Box 73. Center for the History of Medicine, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard University.

- 15. Baumgartner L. Confidential Health Education Literature Memo From Leona Baumgartner to Mr. Abe Brown, Acting Director of Health Education. September 26, 1955. Box 43. Center for the History of Medicine, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard University.

- 16.Gardner MN, Brandt AM. “The doctors’ choice is America’s choice”: the physician in US cigarette advertisements, 1930–1953. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):222–232. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smoking Menace. Baltimore Sun. 1958:TV19.

- 18.Cohn V. Smokers increase risk of losing their babies. Washington Post. October 13, 1977:C10. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brody JE. Personal health; reducing the coronary risk factors. New York Times. August 3, 1977:49. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ubell E. How to gauge your smoking madness. Chicago Tribune. November 12, 1973:B11. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baumgartner L. “Knowing Is Not Enough,” Introduction to the CBS National Health Test, sent to CBS September 3, 1969. Box 73. Center for the History of Medicine, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard University.

- 22.Brandt AM. The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Cancer Society. Smoking stinks. 1978. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bQVNGFYSYts. Accessed April 26, 2016.

- 24.American Cancer Society. Don’t Be a Draggin’ Lady. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KAKnapx1xmU. Accessed June 14, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harder J 1981 American Lung Association PSA. Featuring Brooke Shields. 1981. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gj7-6T2tTMI. Accessed April 26, 2016.

- 26.Fairchild AL, Bayer R. Public health with a punch: fear, stigma, and hard-hitting media campaigns. In: Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG, editors. Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2018. pp. 429–438. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dworkin G. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 1997. Mill’s On Liberty: Critical Essays. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill D, Chapman S, Donovan R. The return of scare tactics. Tob Control. 1998;7(1):5–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakefield MA, Coomber K, Durkin SJ et al. Time series analysis of the impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence among Australian adults, 2001–2011. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(6):413–422. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.118448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zacher M, Bayly M, Brennan E et al. Personal tobacco pack display before and after the introduction of plain packaging with larger pictorial health warnings in Australia: an observational study of outdoor café strips. Addiction. 2014;109(4):653–662. doi: 10.1111/add.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Advisory Committee on AIDS. Grim reaper. 1987. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U219eUIZ7Qo. Accessed February 8, 2017.

- 32.Kramer L. 1,112 and counting—a historic article that helped start the fight against AIDS. Available at: https://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2003/05/66488.html. Accessed June 12, 2018.

- 33.Shilts R. And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. 20th-anniversary edition. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press; 2007.

- 34.Watney S. Taking liberties. In: Carter E, Watney S, editors. Taking Liberties: AIDS and Cultural Politics. London, UK: Serpent’s Tail; 1989. pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mann JM, Gostin L, Gruskin S, Brennan T, Lazzarini Z, Fineberg HV. Health and human rights. Health Hum Rights. 1994;1(1):6–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM et al. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. JAMA. 2000;284(2):198–204. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harawa NT, Greenland S, Bingham TA et al. Associations of race/ethnicity with HIV prevalence and HIV-related behaviors among young men who have sex with men in 7 urban centers in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(5):526–536. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gross M. The second wave will drown us. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):872–881. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. The Last Watch. “HIV Is No Picnic” ad campaign. Available at: http://www.thelastwatch.com/SAPPinicAds.html. Accessed April 29, 2016.

- 41.Advocate.com editors. New HIV ad campaign hits a nerve. 2002. Available at: https://www.advocate.com/news/2002/11/09/new-hiv-ad-campaign-hits-nerve-6913. Accessed June 12, 2018.

- 42.Bor J, Niedowski E. Experts on AIDS fear gay male complacency: young men less aware of disease’s devastation. 2002. Available at. http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2002-12-04/news/0212040031_1_gay-men-infected-young-adults . Accessed June 12, 2018.

- 43.Fierstein H. The culture of disease. 2003. Available at. http://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/31/opinion/the-culture-of-disease.html . Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 44.Lee M. Safety campaign ads, the good and the bad. 2009. Available at. https://www.youth.sg/Peek-Show/2009/5/Safety-campaign-ads-the-good-and-the-bad . Accessed April 28, 2016.

- 45.Sydney Morning Herald. Be afraid, not ashamed, says safe sex campaign. 2010. Available at. http://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/diet-and-fitness/be-afraid-not-ashamed-says-safe-sex-campaign-20100102-lmsi.html . Accessed April 28, 2016.

- 46.Coddon K. Has the AIDS message gone missing? The Cairns Post. April 13, 2007, 19. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Travis D. Don’t forget AIDS danger. Geelong Advertiser. December 11, 2007, 13. [Google Scholar]

- 48.New Australian STI prevention campaign: “Always wear a condom.” 2010. Available at. http://www.examiner.com/slideshow/new-australian-sti-prevention-campaign-always-wear-a-condom. Accessed April 28, 2016.

- 49.Semansky M Bristol Myers-Squibb expands One Life to Live HIV campaign. 2010. Available at: http://www.marketingmag.ca/brands/bristol-myers-squibb-expands-one-life-to-live-hiv-campaign-5312. Accessed April 22, 2016.

- 50.Fairchild AL, Bayer R, Colgrove J. Risky business: New York City’s experience with fear-based public health campaigns. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(5):844–851. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hartocollis A. City’s graphic ad on the dangers of H.I.V. is dividing activists. 2011. Available at. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/04/nyregion/04hiv.html . Accessed April 28, 2016.

- 52.White MC. H.I.V. education that aims to empower, not shame. 2015. Available at. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/28/business/media/hiv-education-that-aims-to-empower-not-shame.html . Accessed April 28, 2016.

- 53.Lupton D. A postmodern public health? Aust N Z J Public Health. 1998;22(1):1–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Logie C, Gadalla TM. Meta-analysis of health and demographic correlates of stigma towards people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21(6):742–753. doi: 10.1080/09540120802511877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hatzenbuehler ML, O’Cleirigh C, Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA. Prospective associations between HIV-related stigma, transmission risk behaviors, and adverse mental health outcomes in men who have sex with men. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(2):227–234. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9275-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sowell RL, Lowenstein A, Moneyham L, Demi A, Mizuno Y, Seals BF. Resources, stigma, and patterns of disclosure in rural women with HIV infection. Public Health Nurs. 1997;14(5):302–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1997.tb00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burris S. Stigma, ethics and policy: a commentary on Bayer’s “Stigma and the ethics of public health: not can we but should we.”. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):473–475. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.020. discussion 476–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Callahan D. Obesity: chasing an elusive epidemic. Hastings Cent Rep. 2013;43(1):34–40. doi: 10.1002/hast.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nussbaum MC. Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]