Military medicine has advanced US trauma and emergency care from the Civil War to the present day. What is less well known is that military medicine has profoundly influenced public health as well. In fact, the US military’s contributions go back to the earliest days of our republic. In 1777, while in winter quarters, General George Washington ordered that every soldier in the Continental Army who had not previously had smallpox be inoculated against the disease. This was the first time an army was immunized by command order. Washington also instituted policies on camp cleanliness and took additional measures to preserve his army’s fighting strength. The concepts he championed still guide military preventive medicine.

HEALTH PROTECTION

The importance of health protection grew during the US Civil War. Appalled that the Union Army was losing more soldiers to disease than in battle, President Abraham Lincoln appointed the US Sanitary Commission. The commission named Major Jonathan Letterman medical director of the Army of the Potomac. Letterman understood, like General Washington before him, the importance of public health. The reforms he championed in battlefield care and camp hygiene established the military medical officer as the commander’s top advisor for ensuring the health of the force. Writing shortly after the Civil War, Letterman observed:

A corps of medical officers was not established solely for the purpose of attending the wounded and sick. . . . The leading idea is to strengthen the hands of the Commanding General by keeping his army in the most vigorous health, thus rendering it, in the highest degree, efficient for enduring fatigue and privation, and for fighting.1(p180; emphasis added)

When the United States subsequently began to project power outside its borders, tropical diseases quickly began to degrade the strength of the force. A surge of deaths from malaria and yellow fever during the Spanish–American War prompted the US Army to start investing in infectious disease research. This led to important discoveries about vector-borne illness, antibiotics, insect repellants, and vaccines—all of which paid huge dividends when applied to the civilian sector. More recent examples of military-driven innovations that have civilian applications are vaccines against malaria, HIV, and enteric diseases2 and portable chlorine makers for safe and sustainable drinking water in low-resource communities (http://bit.ly/2uj9KLO).

HEALTH PROTECTION PARTNERSHIP

In the military today, as it was in the past, health protection is a partnership: commanders rely on their medical officers to identify threats and recommend appropriate countermeasures, and medical officers rely on their commanders to adopt and enforce appropriate actions to protect the health of the unit. To ensure consistent application of this principle, the Department of Defense mandates that every commander plan, implement, and enforce a health program that “effectively anticipates, recognizes, evaluates, controls and mitigates health threats encountered during deployments” (DODI 6490.03, 30 Sep 2011, p. 2). The commander must also implement comprehensive health surveillance “to promote, protect, and restore the physical and mental health of DoD personnel throughout their military service” (DODD 6490.02E, 3 Oct 2013, p. 2). To accomplish this task, commanders and their medical officers monitor multiple health-related metrics. These include monitoring preventive health assessment data, dental health status, immunization rates, and measures of unit mental health and resiliency.

DISEASE AND NONBATTLE INJURY RATE

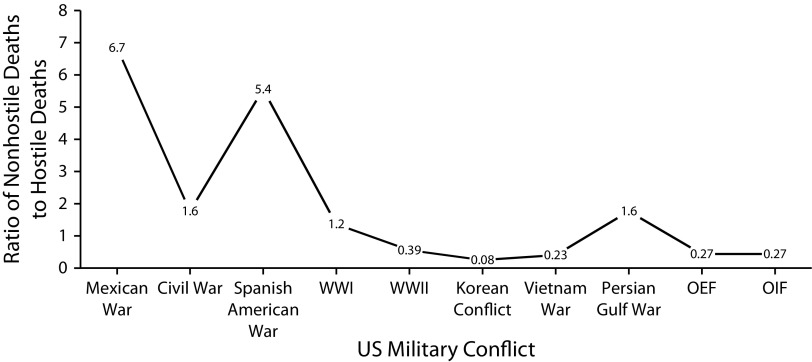

When a unit is deployed, efforts to maintain health are expanded to include camp cleanliness and measures to prevent vector-borne and communicable diseases and ensure food and water safety. Protecting the health of the force is so important, military medical officers and commanders are required to monitor and report their unit’s disease and nonbattle injury (DNBI) rate—broadly defined as the rate of disabling illnesses and injuries caused by factors other than enemy action. A high DNBI rate before, during, or after deployment may indicate that a medical officer failed to properly discharge his or her duties, the commander disregarded the input, or the unit failed to follow orders. Because health protection is a command responsibility, a unit’s DNBI rate is widely considered a measure of leadership (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Ratio of Nonhostile Deaths to Hostile Deaths for Major US Military Conflicts

Note. OEF = Operation Enduring Freedom; OIF = Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Source. The data were adapted from Casualty Summary by Casualty Category, Defense Casualty Analysis System (DCAS 2.1.10). Available at: https://www.dmdc.osd.mil/dcas/pages/casualties.xhtml. Accessed November 29, 2016.

HEALTH PROTECTION IN THE CIVILIAN SECTOR

Health protection should be valued equally in the civilian sector. Healthy populations are more productive and prosperous than those that are not.3 Occupational health is built on this premise. When strongly backed by senior management, occupational health programs protect a company’s workforce and boost its bottom line. Throughout his tenure as chief commanding officer of Alcoa, Paul O’Neill held his plant managers accountable for the well-being of their workers. As a result, Alcoa’s lost work days attributable to injury plummeted from 1.86 per 100 workers to 0.20. By the time O’Neill left the company to become the US treasury secretary, Alcoa’s net income was five times higher than when he started.4

Factors that distinguish the military health protection from civilian public health include a doctrinal commitment to workforce health, the command authority of military leaders, and each service member’s consent, upon enlistment, to follow this authority. Because free societies value individualism and choice, public health practitioners and the leaders they serve must strike a balance between personal preferences and the risks and cost of disease. If a public health measure is not backed by the force of law or company policy, civilian leaders must persuade rather than direct. They can focus organizational goals and allocate resources to reward healthy behaviors, establish and track meaningful metrics, consistently communicate the value of public health, and accept accountability for their actions.

Although more innovation in civilian health protection is needed, good examples exist. Recent elections in New York City and London included dialogue about the potential for focused governance and accountability of politicians for community nutrition and food awareness.5 Health in All Policies, an innovation supported by the American Public Health Association, provides a concrete roadmap to civilian health protection by embedding health considerations into decision making across multiple sectors.6

Imagine if every civilian sector leader—including corporate chief executive officers, mayors, and governors—were evaluated, at least in part, on the health metrics of their company, community, or state. It could have a profound impact on Americans’ health. As the old adage “What gets measured, gets managed” suggests, the first step is to harness available data on a population’s health and draw a direct connection to the quality of its leadership.

A national commitment to health protection—reinforced by holding leaders accountable for results—would improve population health, reduce health care spending, and boost our nation’s economy.7 Just as lessons learned on the battlefield advanced civilian trauma and emergency care, widespread adoption of health protection—Major Letterman’s “leading idea”—could transform our nation’s focus from “sick care” to “health care.”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Thomas Travis, former surgeon general of the US Air Force, for his comments on an earlier draft of this editorial.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mazzzuchi JF, Trump DH, Riddle J, Hyams KC, Balough B. Force health protection: 10 years of lessons learned by the Department of Defense. Military Medicine. 2002;167(3):179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitchen LW, Vaughn DW. Role of US military research programs in the development of U.S. licensed vaccines for naturally occurring infectious diseases. Vaccine. 2007;25(41):7017–7030. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom DE, Canning D. The health and wealth of nations. Science. 2000;287(5456):1207–1209. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baer D. How changing one habit helped quintuple Alcoa’s income. 2014. Available at: http://www.businessinsider.com/how-changing-one-habit-quintupled-alcoas-income-2014-4. Accessed January 14, 2017.

- 5.Freudenberg N, Atkinson S. Getting food policy on the mayoral table: a comparison of two election cycles in New York and London. Public Health. 2015;129(4):295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shankardass K, Muntaner C, Kokkinen L et al. The implementation of Health in All Policies initiatives: a systems framework for government action. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0295-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin GC, Goldman L, Hernández S Advancing the health of communities and populations: a vital direction for health and health care. 2016. Available at: https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Advancing-the-Health-of-Communities-and-Populations.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.