Abstract

Before the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), many Americans with disabilities were locked into poverty to maintain eligibility for Medicaid coverage. US Medicaid expansion under the ACA allows individuals to qualify for coverage without first going through a disability determination process and declaring an inability to work to obtain Supplemental Security Income. Medicaid expansion coverage also allows for greater income and imposes no asset tests.

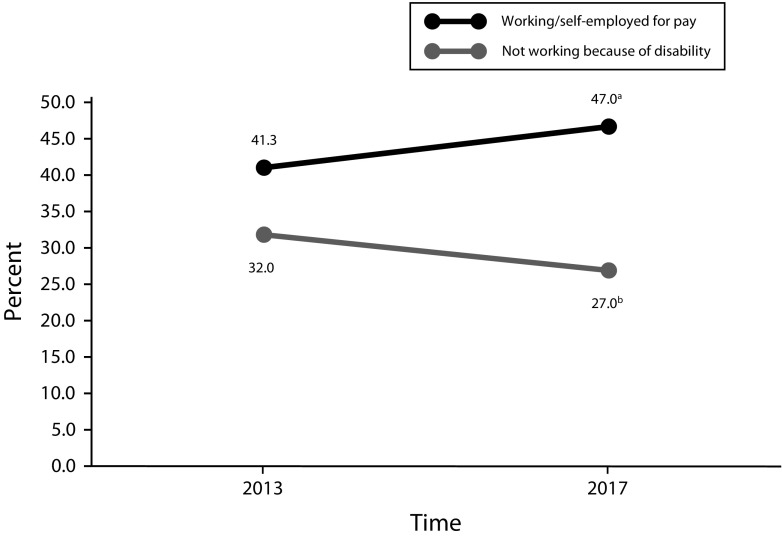

In this article, we share updates to our previous work documenting greater employment among people with disabilities living in Medicaid expansion states. Over time (2013–2017), the trends in employment among individuals with disabilities living in Medicaid expansion states have become significant, indicating a slow but steady progression toward employment for this group post-ACA.

In effect, Medicaid expansion coverage is acting as an employment incentive program for people with disabilities. These findings have broad policy implications in light of recent changes regarding imposition of work requirements for Medicaid programs.

Historically, people with disabilities often have been locked into poverty to maintain eligibility for categorical Medicaid coverage because of strict limits on income and assets.1,2 Because earnings and savings could result in loss of critically needed coverage, Medicaid acted as a work disincentive for many Americans with disabilities. Research we conducted 2 years after implementation of Medicaid expansion under The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; Pub L No. 111-148, 124 Stat 855 [March 2010]), however, showed that employment rates for people with disabilities were greater in states that expanded Medicaid than in states that did not expand Medicaid, indicating that higher earning thresholds and no asset testing associated with Medicaid expansion coverage allowed people with disabilities to increase their employment in those states.2 We update findings regarding 2017 trends in employment among people with disabilities in Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states and discuss associated public health and policy implications.

TRENDS WORTH WATCHING

In our previous work,2 data from the nationally representative Health Reform Monitoring Survey indicated that trends in the share of adults with disabilities who reported employment increased in Medicaid expansion states but decreased in nonexpansion states, even after controlling for local employment rates. At that time, the difference in trends between expansion and nonexpansion states was not statistically significant, perhaps because of a relatively small sample size in the pre-ACA period and a likely time lag between availability of Medicaid expansion coverage and the opportunity to obtain employment. We used the same analytic techniques (including controlling for local employment rates), but with the addition of data through September 2017, to reexamine trends in employment among adults with disabilities living in Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states. Respondents were considered to have a disability and included in the analyses if they answered yes to this question: “Do you have a physical or mental condition, impairment, or disability that affects your daily activities OR that requires you to use special equipment or devices, such as a wheelchair, TDD [telecommunications device for the deaf], or communications device?”

With the additional data, significant trends and differences between them are beginning to emerge (Figure 1). We used a difference in differences design to first examine trends in the share of adults with disabilities who reported not working because of a disability before and after implementation of the ACA and Medicaid expansion. In Medicaid nonexpansion states, most adults with disabilities must continue to apply for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and undergo a disability determination process affirming that they cannot substantially work to be eligible for Medicaid. It was not surprising then that we found no significant change in the share of adults reporting not working because of a disability (P = .42) in nonexpansion states, where a disability determination is still necessary for Medicaid eligibility. In Medicaid expansion states, however, a significant change over time was found: people with disabilities were significantly less likely to report not working because of a disability post-ACA compared with pre-ACA (P = .036). This finding indicates that in Medicaid expansion states, the need for adults with disabilities to prove an inability to work to obtain Medicaid coverage is decreasing. A 2017 study3 identified a similar trend when examining rates of applications for SSI in Medicaid expansion states: SSI applications in those states declined by more than 3% while increasing in nonexpansion states.

FIGURE 1—

Trends in Working and Not Working Because of Disability in Medicaid Expansion States: United States, 2013 and 2017

Note. Effects are adjusted for individual characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, primary language, education, marital status, family income, health status) and geographic characteristics (metropolitan status, region, and age- and gender-matched local employment) at each wave of data collection. States implementing the Medicaid expansion as of December 2014 include AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, DC, HI, IL, IA, KY, ME, MD, MS, MN, NH, NJ, NM, ND, NV, NY, OH, OR, RI, VT, WA, and WV.

Source. Authors’ analyses of Health Reform Monitoring Survey, 2013–2017; based on multivariable logistic regressions and predictive margins of time (pre–Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act [ACA], 2013, vs post-ACA, 2017) and Medicaid expansion status.

aWald test P = .09.

bWald test P = .036.

Next, we examined trends in the share of adults with disabilities who reported being employed or self-employed pre- and post-ACA Medicaid expansions. In nonexpansion states, the share who were employed decreased over time but not significantly (43.5% pre-ACA; 41.4% post-ACA; P = .34). In expansion states, the change over time was positive and approaching significance (41.3% employed pre-ACA; 47.0% employed post-ACA; P = .09). Moreover, we found a difference approaching significance in employment trends between expansion and nonexpansion states (P = .06). The increase in the share of people reporting that they were employed was greater in expansion than in nonexpansion states. These findings correspond with the finding of decreased rates of unemployment resulting from disability in Medicaid expansion states.

Although the difference in differences design has some limitations, controlling for numerous personal and geographic characteristics in the model increases the likelihood that the parallel trends assumption is satisfied and also improves the precision of the estimates. Moreover, the trends noted here are similar to those documented by another study3 indicating that people with disabilities living in Medicaid expansion states were decreasing their rates of both applying for SSI and declaring themselves unable to work because of disability. In those states, they can now access expanded Medicaid without a disability determination.

One might reasonably expect these adults with disabilities first to explore coverage through expanded Medicaid to ensure that it met their needs. Then, having obtained adequate coverage without first needing to declare an inability to work, these individuals might attempt to enter employment. Marginally significant increases in employment over time for people with disabilities in Medicaid expansion states, especially when compared with adults with disabilities living in nonexpansion states, indicate that this process is occurring.

Future research should explore whether the decrease in SSI applications in expansion states includes people with disabilities who received SSI benefits previously but returned to work because Medicaid coverage allowing increased income and no asset tests was available. These trends are certainly worth watching as changes to Medicaid and Medicaid expansion rules continue to occur, particularly regarding work requirements.4

PUBLIC HEALTH AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Four years after implementation of the ACA, numerous studies have documented positive health, life, and work outcomes associated with Medicaid expansion for a wide range of populations. For example, Medicaid expansion is linked to decreases in infant mortality, decreases in medical divorce rates, increases in early detection of cancer, decreases in days of work missed because of illness, and increased insurance coverage for many groups, including youths, veterans, and people of color.5–9 Medicaid expansion also has had positive results for states, including revenue gains, economic growth, and reductions in uncompensated care.8,10 Our findings add to this literature by documenting increased employment and decreased unemployment rates among American adults with disabilities.

These findings are particularly timely given recent decisions by some states to impose work requirements on enrollees in Medicaid expansion programs.4 Our research indicates that coverage through Medicaid expansion by itself acts as a work incentive program for people with disabilities, without imposition of work requirements. Increased employment, coupled with decreased reliance on federal disability benefit programs, among Americans with disabilities will, over time, result in increased tax revenues for states and decreased federal expenditures, while improving quality of life for enrollees.2,11 For Americans without disabilities enrolled in Medicaid, many of whom transitioned from being uninsured to having coverage through Medicaid expansion and were in fair to poor self-reported health before enrollment, consistent access to care may result in improved health over time and increased ability to work.8,12 Policymakers should consider that such changes may take time, much like the gradually increasing trends in employment among people with disabilities shown here.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was developed under the Collaborative on Health Reform and Independent Living with funding from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (grant 90DP0075-01-00), a center within the Administration for Community Living, US Department of Health and Human Services. Funding for the Health Reform Monitoring Survey comes from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (contract 72731).

The authors would like to acknowledge their Collaborative on Health Reform and Independent Living colleagues, Gilbert Gimm of George Mason University and James Kennedy and Elizabeth Wood of Washington State University.

Note. The contents of this article do not necessarily represent the policy of National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research; Administration for Community Living; US Department of Health and Human Services; or Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and one should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The Health Reform Monitoring Survey has institutional review board approval through the Urban Institute’s institutional review board (federal-wide assurance 0189).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kennedy J, Blodgett E. Health insurance-motivated disability enrollment and the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):e16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1208212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall JP, Shartzer A, Kurth NK, Thomas KC. Effect of Medicaid expansion on workforce participation for people with disabilities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):262–264. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soni A, Burns ME, Dague L, Simon KI. Medicaid expansion and state trends in Supplemental Security Income program participation. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(8):1485–1488. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musumeci MB, Garfield R, Rudowitz R. Medicaid and work requirements: new guidance, state waiver details and key issues. January 16, 2018. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-and-work-requirements-new-guidance-state-waiver-details-and-key-issues. Accessed February 26, 2018.

- 5.Bhatt CB, Beck-Sagué CM. Medicaid expansion and infant mortality in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):565–567. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slusky D, Ginther D. Did Medicaid Expansion Reduce Medical Divorce? Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; January 2018. NBER Working Paper 23139. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w23139. Accessed February 26, 2018.

- 7.Soni A, Simon K, Cawley J, Sabik L. Effect of Medicaid expansions of 2014 on overall and early-stage cancer diagnoses. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):216–218. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonisse L, Garfield R, Rudowitz R, Artiga S. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: updated findings from a literature review. March 28, 2018. Available at: https://www.kff.org/report-section/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-findings-from-a-literature-review-issue-brief. Accessed April 18, 2018.

- 9.Zelaya CE, Nugent CN. Trends in health insurance and type among military veterans: United States, 2000-2016. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):361–367. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dranove D, Garthwaite C, Ody C. Uncompensated care decreased at hospitals in Medicaid expansion states but not at hospitals in nonexpansion states. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(8):1471–1479. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns M, Dague L. The effect of expanding Medicaid eligibility on Supplemental Security Income program participation. J Public Econ. 2017;149:20–34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dworsky M, Eibner C. The Effect of the 2014 Medicaid Expansion on Insurance Coverage for Newly Eligible Childless Adults. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2016. [Google Scholar]